?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Studies conducted on caregivers’ satisfaction on child vaccination services were very scarce including the study area. Therefore, this study was aimed to assess satisfaction and associated factors in vaccination service among infant coupled mothers/caregivers attending at public health centers. A cross-sectional study was conducted on 404 infant coupled mothers/caregivers from 15 March to 15 April 2018 in the selected health centers of Hawassa city, Southern Ethiopia. A systematic random sampling technique was applied to collect relevant data through exit interview with an interviewer-administered structured questionnaire. The overall proportion of the mothers/caregivers who satisfied with their children immunization service was 76.7%. In addition, 89.7%, 77.1%, 77.2%, 65.8%, and 68.3% were satisfied with conveniences of waiting area, cleanliness of immunization rooms, distance from nearby health center, service providers approach and waiting time to get service, respectively. In addition, caregivers living closer to health centers were 5.9 times more likely to be satisfied than their counterparts, the adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval [AOR and 95%CI : 5.9(1.6–22.4)]. Caregivers who waited for ≤30 minutes to get service were 7.3 times more likely to be satisfied than those waited for >30 minutes [AOR and 95% CI: 7.3(3.9–13.6)]. The study indicated the overall satisfaction of caregivers concerning vaccination service to be suboptimal. Maternal/caregivers satisfaction plays a great role to follow vaccination schedule properly and completeness of immunization service for their infants.

1. Introduction

Child immunization is one of the most successful and cost-effective global health interventions for reducing worldwide child illness, lifetime disabilities and death.Citation1,Citation2 Internationally, World Health Organization (WHO) established Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) in 1974 with the intention of immunizing every child against infantile tuberculosis, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis and measles within one year of age.Citation2 Every year, more than 10 million children die before celebrating 5 years of birth date, especially in low-and middle-income countries. Most of them die due to a lack of getting effective interventions that would combat common and preventable childhood diseases.Citation3,Citation4 Basic vaccines are estimated to prevent more than 2.5 million children deaths worldwide per year, mainly due to the prevention of measles, pertussis, and tetanus. The WHO has estimated that about 1.5 million children under age 5 years are continued to dying yearly from vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) which means almost 20% of the overall childhood mortality.Citation5

In Ethiopia, the current initiatives and strategies of the routine childhood immunization program are aimed at increasing coverage and lowering the “dropout” rate. Currently, about 10 antigens/vaccines have been providing especially targeting of major killer diseases during childhood in Ethiopia. These vaccines include BCG, polio vaccine, pentavalent that comprises five vaccines (DPT-Hib-HepB), pneumococcal-conjugated vaccine, rotavirus vaccine, and measles. Additionally, the inactivated polio vaccine has been on provision with oral-polio vaccine to strengthen the polio eradication strategy since 2015.Citation6,Citation7 An Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS) report in 2016 indicated only 39% vaccination rates in children with the age group of 12–23 months and that rate wide-ranging considerably through geographical regions, like coverage in the Southern Nation, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR) was 47%.Citation8 Studies conducted in Ethiopia indicated that about 91.7%,Citation9 76%,Citation10 and 73.2%Citation11of the children were fully immunized. About 20.3% were partially immunized and 6.5% were not vaccinated.Citation11 About 6.5%, 2.7%, and 4.5% were dropout rates for BCG to measles, Penta 1 to Penta 3, and Pneumonia 1 to Pneumonia 3, respectively.Citation10

Client satisfaction is a fundamental component of health service and it directly related to the utilization of health services and it is the extent to which the clients feel that their needs and expectations are being met by the service that provided.Citation12 Also, client satisfaction is the immediate outcome of the service provided, and mothers/caregivers should be informed about the benefits/importance of child vaccination.Citation13 The study report from Nigeria indicated 96.7% of satisfaction level among mothers who received the service. This imitates that clients may generally express satisfaction to the quality of services despite some inconsistencies between received care and their expectations.Citation12 In similar, nearly all mothers (97%) were satisfied in India regarding the services they have received during exit interviews, even though 43% had waited more than 30 minutes to get service.Citation14 Whereas the study conducted in the Jigjiga zone, Ethiopia indicated the overall 53.3% of mothers/caregivers satisfaction rate in vaccination service.Citation15 Other studies conducted in Northern part of Ethiopia revealed 85.7%,Citation16 and 53%Citation15 of infant coupled caregivers were satisfied with the convenience of waiting area and cleanliness of immunization room, respectively.Citation15 However, the study conducted in Nigeria indicated that majority of the caregivers were responded regarding poor sanitation of immunization rooms.Citation17 Moreover, mother educational status, mothers’ awareness to availability of vaccines, mothers’ knowledge to vaccine schedule of their site, place of child delivery, and living altitude were an important predictors of caregivers’ satisfaction concerning their children vaccination.Citation11

The child immunization program is very crucial for the reduction of child morbidity, permanent disability, and mortality. However, there is no supportive data regarding caregivers’ satisfaction in their children immunization services in the public health centers in the study area, this study aimed to assess satisfaction and associated factors among infant coupled mothers/caregivers attending in selected public health centers of Hawassa city.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population and study settings

This study was conducted from March 15 to April 15/2018 in the selected health centers of Hawassa city administration, Southern Ethiopia. The city is serving as the capital city of southern nations, nationalities, and people regional state. It is 275 km far away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, and geographically located 130 km from Wolaita Sodo in the east direction, 75 km from Dilla in North direction, and 22 Km from Shashemene at South direction. The city administration has an area of 157.2 km2 divided into 8 subcities and 32 kebeles. According to the 2017/18 central statistical authority projection, the total population of the town is 367,907. The children age less than 1 year were estimated to be 11,736. There are 380 technical staffs serving in the office of the Hawassa city health department. Concerning the health infrastructure, there are 6 hospitals (1 referral, 1 district and 4 private), 10 public health centers and 53 private clinics.Citation18 Infants coupled mothers/caregivers’ who came to the randomly selected health centers for the immunization service with the infant age less than one year were eligible for the satisfaction level study by using exit interview. From 10 public health centers, five (Millennium, Chefe-kotejebesa, Tilte, Gemeto, and Gararikta) were selected for the study using the lottery method.

2.2. Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical committee of Jimma University College of public health and medical sciences. A clearance letter that obtained from Jimma University and the proposal also was submitted to the Hawassa city health department for the necessary review and research go ahead. Then the official supportive letter obtained from Hawassa city health department was submitted to the selected public health centers. Following this, the protocol of the study was well explained to study participants and written informed consent was obtained from each study participant or parents/legal guardians for those infants included in the study. As well, the confidentiality of the participants’ information was strictly kept.

2.3. Sample size and sampling procedure

The sample size was calculated by the assumption of 50% using a single proportion formula at a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Where, n = the required sample size, Zα/2, which is 1.96 at 95% CI, p = proportion of client satisfaction, q = 1-p, and d = assumed marginal error (5%). In addition, a 10% nonresponse rate was considered and the final sample size calculated to be 422.

The total sample size was proportionally allocated to each health center-based on 1-month flow rate of infant coupled mothers/caregivers to each selected health center for the purpose of immunization service. The trend of flow rate was around 614 in the selected five health centers and the K value was calculated and it was approximately (614/422)≈2. Then systematic random sampling technique was applied every second infant coupled mother/caregiver to assess immunization service satisfaction by an exit interview.

2.4. Data collection

Socio-demographic and vaccination related data were collected using pre-tested an interviewer-administered questionnaire that contains closed ended questions. The questionnaire was prepared by reviewing national immunization guideline and WHO immunization guidelines in order to address the study objective.Citation6,Citation13,Citation19 Then the questionnaire was administered by trained nurses (data collectors) who were selected from other health institutions and they conducted exit interviews in private locations/rooms in the health centers to obtain data from caregivers after the receipt of health care.

2.5. Operational definitions

2.5.1. Caregiver

It is the most responsible person that takes care of a child less than 12 months of age that brings child for immunization service in health centers.

2.5.2. Convenience of waiting area

It is the clean, well ventilated, and comfortable with adequate seats and enough physical space for clients in the health center to wait until they get service.

2.5.3. Cleanliness of immunization rooms

It is a properly sanitized and dirt free of the immunization rooms.

2.5.4. Caregiver’s satisfaction

the interaction between caregivers and vaccination service providers in different aspects like vaccination service provider related factors, the availability of services, distances of service providing nearby heath institution and health institution related factors. The satisfaction was assessed by satisfaction indicators (items), and presented using a 5-point Likert scale (1-very dissatisfied, 2-dissatisfied, 3-neutral, 4-satisfied, and 5-very satisfied). The caregivers’ overall satisfaction was classified into two categories: satisfied and unsatisfied by using cut point that was calculated using the demarcation threshold formula: [(Total the highest score-Total the lowest score)/2 + Total the lowest score]. The caregivers scored below the threshold level (cut point) were categorized as “unsatisfied” whereas those scored greater than or equal to the threshold level were categorized as “satisfied.”Citation20

2.6. Statistical analysis

The data completeness was checked visually, entered in to Epi-data version 3.1 and then exported to statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 23 for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics (mean, SD, frequency and percentage) were used. Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis models were used to assess statistical differences in categorical variables. In addition, a variable with P-value <0.25 in the bivariable logistic regression analysis was used as a cutoff to consider the variable in multivariable analysis and alpha was set at 5% for statistical significance at 95% CI.

2.7. Data quality control

The quality of data was ensured through training of data collectors, supervisors and pretesting of the questionnaires. The English version questionnaire was translated into Amharic then back to English to ensure consistency; and finally, the Amharic version was used for data collection. The data collectors were trained on data collection procedure, communication approach with respondents and ethical issues, In addition, to assess the internal consistency of the caregiver satisfaction tool, a pretest was conducted on 5% questionnaire other than the study sites and correction was done based on pretest feedback prior to actual data collection. Moreover, the Cronbach’s alpha of the pretest was 0.864.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of caregivers

Among 422 mothers/caregivers approached, 404 were participated in exit interviews with a 95.7% response rate. About 365(90.3%) of caregivers were females and the mean age of the participants was 27.9 (±4.3) years and 42.1% were aged between 26 and 30 years. Regarding marital status, 96.5% of mothers/caregivers were married; 39.6% and 52.2% were educationally greater than or equal to diploma and protestant religion followers, respectively. Moreover, almost 41% of the participants were housewives followed by government employee 31.4% ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of infants coupled mothers/caregivers at public health centers of Hawassa city administration

3.2. Health system-related services information

Among 404 mothers/caregivers, 96% were spent less than 30 minutes to reach a particular nearby health center. Totally, 66.3% and 86.6% of the participants were satisfied with the convenience of waiting area and cleanness of the immunization rooms, respectively. Regarding service waiting time, the majority of caregivers (79.5%) got their services at the respective health center for less than or equal to 30 minutes; 86.6% have accepted the cleanness of the immunization room. Service providers counseled 45.5% of the participants concerning the benefits and side effects of the vaccines ().

Table 2. Health system-related information of infants coupled mothers/caregivers in exit interview in the public health centers of Hawassa city administration

3.3. The satisfaction of mothers/caregivers on child immunization services

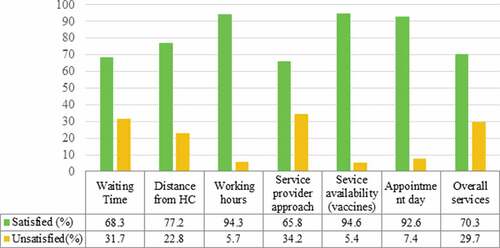

With regard to of waiting time to get service, 257(63.6%) and 13(3.2%) of the mothers/caregivers were satisfied and very satisfied, respectively; while 134(33.1%) were unsatisfied and strongly unsatisfied. Regarding the convenience of working hours, the majority 381(94.3%) of mothers or caregivers were accepted the working time to have their children vaccinated was reasonable, while 22(5.4%) were not accepted and the mean satisfaction score was 3.9(±0.52). In addition, 358(88.6%) and 24(5.9%) of caregivers were satisfied and very satisfied, respectively with the availability of service with respect to the previous appointment. Considering the distance from the health center, 304(75%) of respondents perceived that the time took them to reach nearby health center was appropriate and more than half 235(58.2%) mothers/caregivers were satisfied with respect to the approach of service providers during immunization session with a mean satisfaction score of 3.7(±0.72).

Moreover, the majority, 362(89.6%) of mothers/caregivers were satisfied with the appointment date with a mean satisfaction score of 3.9(±0.56). Two hundred fifty-eight (63.9%), 26(6.4%) and 87(21.5%) of mothers/caregivers were satisfied, very satisfied and neutral, respectively with respect to the overall immunization services provided to their children ().

Table 3. Satisfaction of infant coupled mothers/caregivers on each satisfaction indictor items at public health centers of Hawassa city administration

The satisfaction threshold level of an infant coupled mothers/caregivers classification was based on the childhood immunization service assessment indicators (items) score. According to the demarcation threshold formula, the cut point was 25. Caregivers scored below the threshold point were considered as unsatisfied, while those scored greater than or equal to the threshold level were categorized as satisfied. Based on the threshold formula, the overall level of mothers/caregivers’ satisfaction on their child immunization services was 76.7% (310/404). More than three fourth (77.1%) and 89.7% of caregivers were satisfied with conveniences of waiting area and cleanliness of immunization room, respectively. About 94.6%, 94.3%, 65.8%, and 92.6% of the caregivers were satisfied with service availability, working hours of service providers, the approach of service providers and date of appointments, respectively. In addition, 70.3% of the mothers/caregivers were satisfied with the service provided based on their response rate but not using threshold formula ().

3.4. Factors associated with mothers/caregivers satisfaction level on immunization services

In bivariable analysis, mothers/caregivers living closer to health centers (time took ≤30 minutes to reach the nearby health center) were 4.6 times more likely to be satisfied than their counterparts (time took >30 minutes to reach the nearby health center), the crude odds ratio [COR and 95% CI: 4.6(1.7–12.7)]. Mothers/caregivers who waited for less than or equal to 30 minutes to get service were 12.1 times more likely to be satisfied than those waited for more than 30 minutes [COR and 95% CI: 12.1(6.9–21.0)] ()

Table 4. Factors associated with caregivers’ satisfaction on children immunization Services in public health centers of Hawassa city (bivariable analysis)

While independent variables with a P value <0.25 in bivariable analysis were considered for multivariable regression analysis in order to assess factors that associated with mothers/caregivers satisfaction level of their children vaccination services. Based on the statistical analysis, mothers/caregivers living closer to health centers were 5.9 times more likely to be satisfied than their counterparts, the adjusted odds ratio [AOR and 95%CI: 5.9(1.6–22.4)]. Mothers/caregivers who waited for less than or equal to 30 minutes to get service were 7.3 times more likely to be satisfied than those waited for more than 30 minutes [AOR and 95% CI: 7.3(3.9–13.6)] ().

Table 5. Factors associated with caregivers’ satisfaction on children immunization services in public health centers of Hawassa city (multivariable analysis)

4. Discussion

Client satisfaction is considered as one of the anticipated consequences of health care and it directly interlinked with the use of health services. In addition, it indicates the gap between the client expectation and the provision of the health services. Therefore, caregivers who satisfied with service provided will keep using the service in respective institution and this might ultimately help to follow the vaccination schedule and to complete all required vaccinations of their children.

The overall level of mothers/caregivers’ satisfaction on child immunization services at selected public health centers of Hawassa city adminstration was 76.7%. This finding was relatively higher than the study conducted in Somalia region, Ethiopia that was 53.3%.Citation15 Other studies conducted in NigeriaCitation12 and IndiaCitation14 indicated that the overall satisfaction of caregivers was 96.7% and 97%, respectively. The variations might be due to the subjective nature of the respondents, the applied type of indicators and classification to measure satisfaction level between the studies.

Mothers/caregivers who traveled less than or equal to 30 minutes to reach the respective nearby health center were 5.9 times more satisfied than those who traveled more than 30 minutes. Similarly, the study conducted in Nigeria indicated that caregivers traveled <30 minutes to reach nearby health centers were 2.6 times more likely to be satisfied when compared to their counterparts.Citation21 On the contrary, the study conducted in Iraq indicated an insignificant association of caregivers’ satisfaction with the distance from nearby health institutions.Citation22 This difference in satisfaction level might be attributed to the fact that mothers/caregivers subjective perception towards service provision in similar situations, different perceptions by different caregivers and giving due attention to the service they got regardless of the distance they traveled.

The present study indicated about 90.3% of caregivers who waited for less than 30 minutes to get service were 7.3 times [AOR (95%CI): 7.3(3.9–13.6)] more likely to be satisfied than those who waited for more than 30 minutes. In similar, the study reports from other part of EthiopiaCitation15and NigeriaCitation23indicated that caregivers who waited for more than 30 minutes to get service were 51% and 56%, respectively and the caregivers were less likely to be satisfied when compared those who waited for less than 30 minutes to get service. Conversely, even though 97% of caregivers were satisfied with the service provided, however, a high rate (43%) of caregivers were waited for more than 30 minutes to get service in India.Citation14 This variation might be related to caregivers’ subjective judgment and expectation along with the acceptability of the service in a different manner under similar situations and some caregivers focus on the services they wanted to be provided with irrespective of service waiting time.

The current study indicated that caregivers who positively responded regarding the convenience of waiting areas were 77.1%. The finding was lower than the study conducted in Northern Ethiopia, in which caregivers who agreed with the convenience of waiting area were 85.7%.Citation16 Conversely, the study conducted in India indicated insignificant effect of waiting area suitability on caregivers’ satisfaction level.Citation14 This might be due to the fact that some caregivers give attention only to have their children vaccinated irrespective of the situation of waiting area. Furthermore, inconveniences of waiting area strongly affect the satisfaction of caregivers and in support, the studies conducted in Nigeria indicated non-comfortability/non-conduciveness of waiting area due to inadequate seats or overcrowding were major reasons for lowering caregivers’ satisfaction on their child immunization service.Citation17,Citation21

We found that caregivers who agreed on the cleanliness of the immunization room was 89.7%. The finding is not comparable with the study reported from Nigeria that majority of the caregivers were agreed with the uncleanness of the immunization room.Citation17 The difference might be attributed to different subjective judgment and perception of caregivers toward similar situations, giving more or less attention to the service environment of real situations.

5. Strength and limitations of the study

As the strength of the study, we included about five public health centers of Hawassa city adminstration to address caregivers’ satisfaction level in vaccination service of the children. In addition, we used flexible approach when conducting the exit interviews in private rooms that are found in the health centers.

As limitations, first, we did not observe the service provider’s/health staff’s communication approach with caregivers at the time of infant’s vaccination rather than asking caregivers in exit interview. Second, data are limited to clients’ satisfaction experience to public health centers thus limiting generalization to the overall health facility approach in vaccination service. Third, there is a likelihood of selection bias in caregivers who did not visit the vaccination clinic could not have the chance to participate in the study. Fourth, we did not assess the qualitative methods to get an in-depth sympathetic of the causes of caregivers satisfaction to address the findings from different informants and situations like mothers/caregivers, heath-care workers and mothers in focus group deliberations. Fifth, we used demarcation threshold formula to classify satisfaction level and a varied rate might be observed if we used other classification methods and lack of inferring causality due to cross sectional nature of the study. Irrespective of the described limits, this study provides supportive evidence in the scarce data condition of Ethiopia.

6. Conclusion

This study indicated the overall satisfaction of caregivers concerning vaccination service was suboptimal (76.7%). The distance from nearby health center, waiting time for accessing service, convenience of waiting area and cleanliness of immunization room were important predictors of caregivers’ satisfaction. Maternal/caregivers satisfaction about vaccination plays a great role to follow vaccination schedule and completeness of their infants’ vaccination. It further requires caregivers’ knowledge regarding vaccination. In addition, caregivers satisfaction can also be affected by other factors such as distance from nearby health institution, waiting time, conveniences of waiting area and cleanness of immunization rooms. Therefore, more efforts could be done to assure the provision of client centered vaccination service to inspire caregivers for the completion of vaccination service for their children. This also helps to prevent the outbreaks diseases morbidity, permanent disability and mortality from VPDs. Further, other studies that incorporating observation and qualitative approach are recommended in order to assess the gaps in satisfaction of immunization service and other associated factors in-depth level.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

| AOR | = | Adjusted odds ratio |

| CI | = | Confidence interval |

| COR | = | Crude odds ratio |

| DPT | = | Diphtheria-Pertussis-Tetanus |

| SPSS | = | Statistical package for social sciences |

| VPD | = | Vaccine preventable diseases |

| WHO | = | World Health Organization |

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the Hawassa city adminstration health department, nurses, and supportive staffs who were working in study-selected health centers for their invaluable support during data collection. Further, our gratefulness is also extended to mothers/caregivers for their willingly involvement in the study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO, UNICEF WB. State of the world’s vaccines and immunization. Geneva, World Health Organization, [Internet]. Hum Vaccin. 2009. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44169/9789241563864_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- World Health Organization (WHO). Principles and considerations for adding a vaccine to a national immunization program: from decision to implementation and monitoring. [Internet]. World Health Organ. 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/111548/1/9789241506892_eng.pdf

- Arevshatian L, Clements CJ, Lwanga SK, Misore AO, Ndumbe P, Seward JFTP. An evaluation of infant immunization in Africa: is a transformation in progress? Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(6):449–57. doi:10.2471/BLT.06.031526.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Vaccines and global health: ethics and policy. Mon Arch. 2017. https://centerforvaccineethicsandpolicy.net/

- World Health Organization (WHO). Immunization, vaccines and biologicals. Fact sheets on immunization coverage. World Health Organization; 2017.

- Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH), Addis Ababa E. Ethiopia National expanded program on immunization. Comprehensive multi-year plan 2015–2020. Federal Ministry of Health, Ethiopia; 2015.

- WHO/UNICEF/FMOH. Ethiopian National expanded programme on immunization: comprehensive multi-year plan 2011–2015. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): FMOH; 2010. http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Ethiopia/ethiop_cmyp_latest_revised_may_12_2015.pdf.

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) Ethiopia, ICF. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016. Addis Ababa (Ethiopia and Maryland): CSA and ICF; 2017. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR328/FR328.pdf.

- Gualu T, Dilie A. Vaccination coverage and associated factors among children aged 12–23 months in Debre markos town, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Adv Public Health. 2017;2017:1–6. doi:10.1155/2017/5352847.

- Kassahun MB, Biks GA, Teferra AS. Level of immunization coverage and associated factors among children aged 12–23 months in Lay Armachiho District, North Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:239.

- Animaw W, Taye W, Merdekios B, Tilahun M, Ayele G. Expanded program of immunization coverage and associated factors among children age 12–23 months in Arba Minch town and Zuria District, Southern Ethiopia, 2013. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):464. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-464.

- Timane AJ, Oche OM, Umar KA, Constance SE, Raji IA. Clients ’ satisfaction with maternal and child health services in primary health care centers in Sokoto metropolis, Nigeria. Edorium J Matern Child Health. 2017;2:9–18.

- World Health Organization. Immunization in practice: a practical guide for health staff – 2015 update. World Health Organization; 2015. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/193412/9789241549097_eng.pdf;jsessionid=7401B2696E3F3A89400A70FE7145B901?sequence=1

- Amin R, De Oliveira TJCR, Da Cunha M, Brown TW, Favin M, Cappelier K. Factors limiting immunization coverage in urban Dili, Timor-Leste. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2013;14(3):417–27. doi:10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00115.

- Salah AA, Baraki N, Egata G, Godana W. Evaluation of the quality of Expanded Program on immunization service delivery in primary health care institutions of Jigjiga Zone Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia. European Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;3(4):117-23.

- Hussen A, Bogale AL, Ali JH. Parental satisfaction and barriers affecting immunization services in rural communities: evidence from North Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2016;4(5):408–14. doi:10.11648/j.sjph.20160405.17.

- Oku A, Oyo-Ita A, Glenton C, Fretheim A, Ames H, Muloliwa A, Kaufman J, Hill S, Cliff J, Cartier Y, et al. Perceptions and experiences of childhood vaccination communication strategies among caregivers and health workers in Nigeria: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0186733. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186733.

- South Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR), Regional health bureau: Hawassa town health department, annual report. 2016 17.

- Sambo L, Chatora R, Goosen E. Tools for assessing the operationality of district health systems. [Internet]. Brazzaville: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa; 2003. http://www.who.int/entity/management/district/assessment/assessment_tool.pdf.

- Argago TG, Hajito KW, Kitila SB. Client ’ s satisfaction with family planning services and associated factors among family planning users in Hossana Town public health facilities, South Ethiopia : facility-based cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Midwifery. 2014;7:75–83.

- Fatiregun AA, Ossai E. Clients ’ satisfaction with immunisation services in the urban and rural primary health centres of a South-Eastern State in Nigeria. Niger J Paed. 2013;41(4):375–82. doi:10.4314/njp.v41i4.17.

- Aziz KF. Client’s satisfaction in primary health care centers toward immunization services in Erbil -IRAQ. Med J Babylon. 2015;12:502–08.

- Ne U, An G, Aj E, Dst O. Client views, perception and satisfaction with immunisation services at primary health care facilities in Calabar, South-South Nigeria. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2010;3(4):298–301. doi:10.1016/S1995-7645(10)60073-9.