?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Minimizing vaccine wastage and associated costs is considered a key target for appropriate vaccine management. In India, the Rotavirus Vaccine (RVV) (2019) and the fractionated injectable polio vaccine (f-IPV) (2016) are more prone to wastage with high procurement costs.

In this operational research study, we determined the effectiveness of a (self-designed) dose based reporting tool (DBRT) in reducing vaccine (f-IPV and RVV) wastage at primary care facilities in India during December 2019 to March’ 2020.

Data reports of all the immunization sessions conducted at three primary care facilities were analyzed to calculate the wastage rates of the RVV and the f-IPV for the following periods: (1). Period of initiation (August-November’ 2019) (2). Pre-intervention with sensitization of healthcare providers (December’ 2019-January’ 2020) (3). Post-intervention after application of the DBRT.

Intervention: The DBRT is a paper-based reporting format that assigns a unique code to each RVV and IPV vial. The health facility is required to report the total doses administered from each coded vial during every immunization session by updating it on the assigned reporting format.

Pre-intervention, the average monthly wastage of f-IPV was 23.5% and of the RVV ranged from 18%-31%. Post-intervention, on using the DBRT, the monthly wastage of both RVV and f-IPV dropped significantly to 8.6% and 11.4%, respectively. During the subsequent month, the IPV wastage further decreased to only 4.7%.

In conclusion, the DBRT reduces vaccine wastage in government primary care facilities by enabling a paper audit trail that promotes responsiveness and accountability among healthcare workers directly involved in vaccine administration.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Vaccination is a lifesaving and cost-effective intervention, which prevented an estimated 10 million deaths and episodes of illness during 2010 and 2015, mostly in low and middle countries (LMICs).Citation1 The introduction of newer vaccines against pneumonia, rotavirus, etc. are likely to further contribute toward the reduction of childhood mortality.Citation2 Furthermore, the planned phasing out of the oral polio vaccine with the injectable polio vaccine (IPV) is a crucial determinant of the polio endgame seeking global elimination of poliovirus, including the vaccine-derived entities.Citation3 However, ensuring universal vaccine coverage of the large child cohorts in LMICs requires a reduction in the escalating cost per vaccinated child.Citation4

Vaccines are a valuable resource, and minimizing vaccine wastage and associated costs is considered a key target for appropriate vaccine management to avoid missed opportunities in vaccinating target beneficiaries.Citation5 Vaccine wastage during a specified period is the proportion of vaccine doses supplied but discarded in either open or unopened vaccine vials without administration to the eligible individual.Citation6 The World Health Organization (WHO) has informed that more than half of all the vaccines produced globally are wasted and recommends the monitoring and reporting of data related to vaccine wastage.Citation5 In this regard, the WHO initiated the open vial policy (OVP) in 2014 to permit reuse of vaccines supplied in multi-dose vials with preservatives for up-to 28 days if maintained in an appropriate cold chain and aseptic conditions.Citation7 Nevertheless, vaccine wastage continues to be a major public health challenge.Citation8 In developing countries with large birth cohorts, vaccine wastage can undermine the coverage of existing vaccines and inhibit the introduction of newer ones due to the escalating costs and logistics.

The Rotavirus Vaccine (RVV) and the fractionated injectable polio vaccine (f-IPV) are significantly more prone to wastage because the former does not adhere to the OVP, while the latter requires the more complicated intradermal route of administration. In India, the RVV and the f-IPV have been introduced in the National Immunization Schedule (NIS) in 2019 and 2016, respectively.Citation9,Citation10 Both vaccines have commonalities in the high-cost of procurement and manufacturing for the Indian government, which is committed to providing the vaccine to beneficiaries free of cost. Due to all these factors, a reduction in the wastage of the IPV and RVV warrants high prioritization in Indian public health settings. Consequently, developing cost-effective interventions with large-scale scalability in primary healthcare facilities, which are the most common public health sites of vaccine administration for infants and children in India, is necessitated.

We, therefore, conducted the present study to determine the effectiveness of a (self-designed) dose based reporting tool in reducing vaccine (f-IPV and RVV) wastage at primary care facilities in India.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted an operational research (intervention) study from December 2019 to March 2020. The study was conducted at two urban and one rural primary care facilities affiliated to the Department of Community Medicine of a government medical college in Delhi. Infants and children are immunized at these health facilities, free of cost. The immunization sessions are conducted at the health facilities by resident doctors and public health nurses of the medical college, which is also the site of vaccine storage and cold chain. Medical undergraduate interns are also provided training at the facility due to it being affiliated to a teaching institution. Approximately 100 infants and children in total are vaccinated at the immunization clinics each week.

Operational definitionsCitation6

Permissible Wastage %: This is the maximum allowed percentage of wastage for a vaccine-type under the National Immunization Schedule. e.g. 10% for IPV, 10% for RVV etc.

Wastage Multiplication Factor (WMF): is used for the estimation of vaccine and logistics. The WMF is calculated using the Permissible Wastage %, as per the following equation:

Actual Vaccine Wastage / Wastage Rate (in %): is calculated by the following equation:

Characteristics of the vaccines

Rotavirus Vaccine (RVV) was introduced in the National Immunization Schedule (NIS) recently after a period of phased countrywide introduction. As per the NIS, the vaccine product used is the Rotavac developed by the Bharat Biotech Company, supplied as a liquid formulation. Rotavac is currently provided to states in a 5-dose vial of 2.5 ml. The recommended dose of Rotavac is five drops, i.e., 0.5 ml, administered orally at 6, 10, and 14 weeks of age along with other age-eligible appropriate vaccines. The vaccine does not adhere to the Open Vial Policy (OVP), and thereby, the vaccine vial is discarded after 4 hours or the end of vaccination session, whichever is earlier, irrespective of the doses remaining in the vial. The allowable wastage of RVV is 10.0%, with a Wastage Factor of 1.11. Thus, it is the only vaccine under NIS, which has a wastage factor of 1.11, despite not adhering to the OVP .Citation10

Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV) was initially introduced in the NIS as an intramuscular (i.m.) dose of 0.5 ml at 14 weeks of age. However, the limited supply of the vaccine was unable to cope up with the demand for the vast birth cohort in India. Hence, the National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization (NTAGI) switched from i.m. dose of IPV to a two-dose (0.1 ml) schedule of intra-dermal fractional-IPV (f-IPV) at 6 and 14 weeks of age. Through this intervention, the administration of fractional doses compared to full-doses increased by five-fold the number of available doses for vaccination. Consequently, each 2.5 ml ml IPV vial is expected to supply 25 doses when the recipient is vaccinated via the intradermal route compared to only 5 doses when vaccinated via the intramuscular route. The allowed wastage for f-IPV is 10.0% with a Wastage Factor of 1.11.Citation9

Methodology

Immunization data reports of all the immunization sessions conducted at the selected sites were analyzed to calculate the monthly wastage rates of the RVV and the f-IPV since August 2019 onwards when the RVV was introduced in the Delhi’s immunization schedule.

Vaccine wastage rates of these vaccines were observed to be much higher than the allowable wastage from August-September’ 2019. In October 2019, the doctors and nurses involved in the immunization session were sensitized toward reducing the vaccine wastage. Based on the feedback received, the vaccine wastage was attributed to the following causes: (i) the administration of the vaccine dose greater than the recommended amount (RVV and f-IPV) (ii). Spillage of the vaccine (f-IPV) during the loading of the dose into the syringe.

Intervention: Based on this feedback, a departmental team supervising the vaccination staff comprising of a senior resident and a faculty member assimilated the feedback for reasons of high-vaccine wastage. Subsequently, they designed a paper format dose-based reporting tool (DBRT) to increase accountability by recording all the doses of the vaccine from each vial that were being used during every immunization session. The DBRT requires the local cold chain handler (in our case at the departmental level) to assign a unique code to each RVV and IPV vial, prefixed with R for a RVV vial and I for an IPV vial. The identification code also included a four-character alphanumeric code that included the alphabetical code as per the month of indent of the vial, and the numeric code as per the serial number of the vial. The format required each health facility to report the doses administered from each coded vial.

Moreover, each dose administered had to be subsequently updated in the provided reporting format by crossing a box against that coded vial entry (Annexure 1). The tool was pretested at one-site during a single immunization session. All the resident doctors and nurses involved in conducting the immunization sessions were trained on how to correctly fill the form during a brief single-day hands-on session. Subsequently, the tool was deployed in the field during February-March 2020 until the abrupt disruption of the vaccination services due to the onset of the COVID-19 epidemic in Delhi.

Statistical analysis

The composite RVV and f-IPV vaccine utilization and wastage data was extracted from the immunization session reports and entered in MS-EXCEL 2016. The data was analyzed with RStudio 0.99 (PBC, Boston, MA) The monthly vaccine wastage rate was calculated for both RVV and f-IPV. Data was represented in frequency and proportions, and also as time trends depicting the vaccine wastage rates. The chi-square test for trend was used to assess for linear trend. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics

The study did not involve any human participants or patients and was a health system operational research. It was exempted by the Institutional Ethics Committee (F.1/IEC/MAMC/(73/01/2020/No149).

Results

Pre-intervention vaccine wastage rates (August-November 2019)

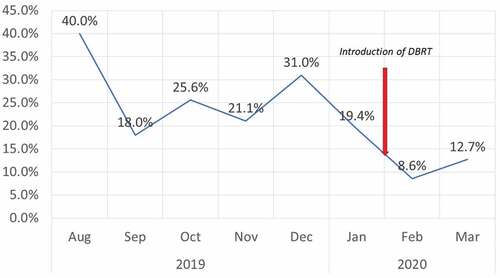

The time-trends of the vaccine wastage rates are depicted in . The monthly wastage factor during the initial month (August 2019) of RVV introduction was very high (40%). However, the higher wastage factor was anticipated as per the RVV deployment algorithm since only infants of 6 weeks of age were administered the vaccine while older infants were excluded. Subsequently, in the second month (September’ 2019), the vaccine was provided to both 6 and 10 weeks old beneficiaries resulting in a reduction in net wastage (18%). However, during the 3rd month (October 2019), when the RVV eligibility included all infants from 6 to 14 weeks of age, the wastage rate was 2.56 times higher (25.6%) than the expected wastage rate of only 10% ().

The wastage rates for IPV during 2019 also revealed a persistently high wastage, with an average monthly wastage of 23.5%, and the maximum monthly wastage rate recorded as 31.8%, nearly three times more than the permissible limit of 10% (). Furthermore, despite the sensitization of doctors and nurses, there was an absence of a significant reduction in vaccine wastage during the next two months (December 2019 – January 2020)

Effectiveness of the intervention (February-March’ 2020)

The DBRT was deployed in the field from February 2020 onwards. The monthly wastage of both RVV and f-IPV dropped significantly (p < .001) to 8.6% and 11.4%, respectively. During the subsequent month, the IPV wastage further decreased to only 4.7%. However, the RVV wastage showed a small uptick and increased to 12.7%, which was slightly higher than the permissive limit but well below the pre-intervention monthly average wastage rates. The intervention was ceased during the last week of March due to the call for lockdown and suspension of routine vaccination services in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. The chi-square test for trend showed a linear trend from December 2019 to March 2020 (p < .001)

Discussion

The present study shows that a paper-based dose based reporting tool with vial coding is highly effective in reducing the vaccine wastage during immunization sessions resulting from incorrect administration of the vaccine due to spillage or injecting higher than recommended doses. Our findings suggest that the DBRT improves the accountability of the healthcare providers involved in vaccination, which translates into lower rates of vaccine wastage.

Previous studies from LMICs have reported widely variable rates of vaccine wastage with the most common causes attributed to incorrect administration of the vaccine, vaccine spillage, wrong technique, and poor awareness of the healthcare workers.Citation11,Citation12 A study in the Gambia by Usuf et alCitation11 reported 18.5–75% vaccine wastage rates of the BCG vaccine. A study in the Surat district of India by Patel et alCitation12 reported all vaccine wastage rates within permissible limits. However, there are no previous studies, which have reported wastage rates of the RVV and f-IPV, vaccines that are significantly more prone to wastage.

The strengths of the intervention are the negligible costs, paper-based format requiring no technological assistance, easy scalability in resource-constrained settings, high feasibility and minimal training requirements among the health personnel. Furthermore, the DBRT can be incorporated within the manual registers used in immunization sessions in primary healthcare facilities across India for the monitoring and reduction of vaccine wastage. The DBRT would also help immunization and program managers within the ambit of the National Immunization Programme to maintain audit readiness related to vaccine wastage in all vaccination sites including those located in resource-constrained settings. The DBRT could also be tweaked to include identity of the staff administering the specific vaccine vials, to help session managers in early recognition of those demonstrating suboptimal performance and provide them with appropriate refresher training.

The study limitations were the unanticipated cessation of vaccination services due to the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic in India, which precluded the possibility of analyzing the trends over a more extended period. Moreover, the effectiveness of the intervention could differ amongst other health personnel involved in vaccination.

Conclusion

The DBRT reduces vaccine wastage in government primary care facilities by enabling a paper audit trail that promotes responsiveness and accountability among healthcare workers directly involved in vaccine administration. Future studies should evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention over longer periods in diverse health settings, including outreach sessions mainly conducted by community nurses (auxiliary nurse midwives). Furthermore, paperless electronic versions of the DBRT that are functional on smartphones and tablets can be designed and assessed toward their effectiveness in comparison to the original paper-based DBRT.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the doctors and nurses involved in provision of vaccination services at our primary care facilities for their diligence and cooperation.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- Ozawa S, Clark S, Portnoy A, Grewal S, Stack ML, Sinha A, Mirelman A, Franklin H, Friberg IK, Tam Y, et al. Estimated economic impact of vaccinations in 73 low- and middle-income countries, 2001–2020. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(9):629–38. doi:10.2471/BLT.16.178475. PMID: 28867843.

- Troeger C, Khalil IA, Rao PC, Cao S, Blacker BF, Ahmed T, Armah G, Bines JE, Brewer TG, Colombara DV, et al. Rotavirus vaccination and the global burden of rotavirus diarrhea among children younger than 5 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(10):958‐965. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1960. PMID: 30105384.

- WHO. The polio eradication endgame: brief on IPV introduction, OPV withdrawal and routine immunization strengthening; 2014 [accessed 2020 May 17]. https://www.who.int/immunization/diseases/poliomyelitis/inactivated_polio_vaccine/brief_ipv_opv_march_2014.pdf?ua=1

- Munk C, Portnoy A, Suharlim C, Clarke-Deelder E, Brenzel L, Resch SC, Menzies NA. Systematic review of the costs and effectiveness of interventions to increase infant vaccination coverage in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:741. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4468-4. PMID: 31640687.

- IVB Biologicals. Monitoring vaccine wastage at country level: guidelines for programme managers. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005.

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Government of India. Immunization handbook for health workers; 2018 [accessed 2020 May 17]. http://www.nrhmtn.gov.in/adv/ImmuHBforHW2018.pdf

- World Health Organization. WHO policy statement: multi-dose vial policy (MDVP) revision; 2014 [accessed 2020 May 17]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/135972/WHO_IVB_14.07_eng.pdf;jsessionid=0D138BA988A284AFB7AC1E7F4258FEB5?sequence=1

- Vaughan K, Ozaltin A, Mallow M, Moi F, Wilkason C, Stone J, Brenzel L. The costs of delivering vaccines in low- and middle-income countries: findings from a systematic review. Vaccine. 2019;2:100034. doi:10.1016/j.jvacx.2019.100034. PMID: 31428741.

- Haldar P, Agrawal P, Bhatnagar P, Tandon R, McGray S, Zehrung D, Jarrahian C, Foster J. Fractional-dose inactivated poliovirus vaccine, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(5):328‐334. doi:10.2471/BLT.18.218370. PMID: 31551629

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Government of India. Operational guidelines: introduction of rotavirus vaccine in the universal immunization program; [accessed 2020 May 17]. https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/Immunization/Guildelines_for_immunization/Operational_Guidelines_for_Introduction_of_Rotavac_in_UIP.pdf

- Usuf E, Mackenzie G, Ceesay L, Sowe D, Kampmann B, Roca A. Vaccine wastage in The Gambia: a prospective observational study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):864. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5762-5. PMID: 29996802

- Patel PB, Rana JJ, Jangid SG, Bavarva NR, Patel MJ, Bansal RK. Vaccine wastage assessment after introduction of open vial policy in surat municipal corporation area of India. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;5(4):233‐236. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.208. PMID: 27239864.