ABSTRACT

Health-care workers are an important vaccination target group, they are more frequently exposed to infectious diseases and can contribute to nosocomial infections. We established a country-wide online monitoring system to estimate influenza vaccine uptake and its determinants among German hospital staff (OKaPII). The online questionnaire included items on vaccination behavior and reasons for and against influenza vaccination. After a pilot phase in 2016, a country-wide roll-out was performed in 2017. Questions on measles (2018) and hepatitis B (2019) vaccination status were added in subsequent years. In 2017, 2018 and 2019 in total 52, 125 and 171 hospitals with 5 808, 17 891 and 27 163 employees participated, respectively. Influenza vaccination coverage in season 2016/17 and 2017/18 was similar (39.5% and 39.3%) while it increased by 12% in 2018/19 (52.3%). Uptake was higher for physicians than for nurses. Self-protection was the most common reason for influenza vaccination. While physicians mainly identified constraints as reasons for being unvaccinated, nurses mainly referred to a lack of vaccine confidence. Of the hospital staff, 87.0% were vaccinated against measles, 6.3% claimed to be protected due to natural infection; 97.7% were vaccinated against hepatitis B. OKaPII shows that influenza vaccination coverage among German hospital staff is low. Occupational group-specific differences should be considered: physicians might benefit from easier access; information campaigns might increase nurses’ vaccine confidence. OKaPII serves as a platform to monitor the uptake of influenza and other vaccines; it also contributes to a better understanding of vaccination behavior and planning of targeted interventions.

Introduction

Health-care workers (HCW) are an important vaccination target group. Due to their profession, they are at increased risk of vaccine-preventable diseases such as influenza, measles or hepatitis B.Citation1–6 In particular influenza can potentially lead to absenteeism and personnel shortages in medical facilities during winter seasons.Citation7 Moreover, HCW can provoke nosocomial infections among vulnerable patients and other staff members.Citation8 Therefore, national vaccination policies for HCW exist in most European countries.Citation9 The German National Immunization Technical Advisory Group (called STIKO) recommends seasonal influenza vaccination to all HCW as well as vaccination against several other vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles and hepatitis B.Citation10

In Germany, the health-care system offers vaccination free of charge to all HCW, when the respective vaccine is officially recommended by the STIKO. Vaccination for HCW is voluntary. However, German law requires the management of health facilities to ensure that all measures are taken to prevent nosocomial infections.Citation11 To achieve this, management can collect and use data on the vaccination status of their employees and – for example – decide about where and how HCW are deployed, if they refuse to get vaccinated. With the new measles protection act endorsed early 2020 a proof of measles immunity will be mandatory for HCW in Germany by mid-2021.

Influenza-associated disease burden is high. In 2017/18, a severe influenza season, Germany had an estimated nine million influenza-related medical consultations, 45 000 influenza-related hospitalizations and 5.3 million cases of work absenteeism.Citation12 Despite evidence that influenza vaccination of HCW not only protects the individual but indirectly also patients, influenza vaccination coverage among HCW remains low in many countries.Citation13 In European countries with data available, influenza vaccination coverage in HCW during seasons 2015/16, 2016/17 and 2017/18 ranged from 16% to 63% (median 30%).Citation14 The highest rates were found in Belgium, England and Wales, and the lowest rates in Italy and Norway. There are no country-level data on influenza vaccination coverage among HCW in Germany from recent years. Hence knowledge about the implementation of recommendations and its drivers is limited. Surveys that were performed in single hospitals and a national health survey from 2009 indicate, however, that influenza vaccine uptake among HCW in Germany is low and varies locally.Citation15–18

While the European region of the World Health Organization (WHO) has committed itself to the elimination of measles, outbreaks continue to occur with an estimated 104 248 cases and 64 deaths in 2019.Citation19 Although the nationwide vaccination coverage in Germany among children is high, vaccination gaps among adults and regional clusters of unimmunized children leave the population susceptible to outbreaks.Citation20 Individuals in medical settings are one of the priority groups for vaccination, as they are at increased risk of being affected by measles outbreaks.Citation5 Control of hepatitis B infection by means of high vaccination coverage is one of the goals of the European Vaccine Action Plan (EVAP).Citation21 In Germany, one strategy to achieve this goal – despite vaccinating children – is to target risk groups for hepatitis B infection, including HCW.Citation10 So far, no country level data on measles or hepatitis B vaccination coverage among HCW exist in Germany.

We established a national online monitoring system on influenza vaccination coverage in German hospitals (OKaPII) as a platform that can (i) identify vaccination gaps in the total target population but also allow stratifications into occupational groups; (ii) assess determinants of vaccination behavior, (iii) observe trends in behavior and acceptance (through annual data collection and standardized study design), and (iv) integrate – in a flexible manner – questions on other vaccines recommended to hospital staff. Data collection started in 2017, we report the first three seasons. OKaPII was designed to give a concise overview on vaccination behavior and acceptance, while acknowledging limited resources and time for participants as well as providing data for potential actions at local level.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participant Recruitment

In a first step we contacted hospitals and asked for their support and participation in the study. The German Hospital Federation sent a letter about the OKaPII study to all its members, while private hospital operators were contacted individually. Additional hospitals were recruited through newspaper articles or conference presentations. As an incentive, participating hospitals were provided with an annual report that summarized clinic-specific results such as the hospital’s influenza vaccination coverage, overall and within different occupational groups, and reasons for and against influenza vaccination among their staff. The report included aggregated results from the other participating hospitals as a benchmark.

For the data collection, we used the web-based Voxco Survey Software (Version 5.5.1 Group Voxco, Montreal, Canada). In each participating clinic a contact person was identified (usually the occupational physician or hygienist) who served as a multiplier. The multipliers forwarded the link to the online survey to all hospital staff via employees’ professional e-mail addresses. Since 2018, we provided flyers with study information and a QR-code to be distributed in hospitals which enabled the participation of hospital staff without access to e-mail. The hospitals decided about any further promotion of the survey. Some hospitals used e.g. e-mail-reminders or posters to recruit more participants. To increase participation, the questionnaire length was kept to a minimum and participants were offered upon completion to take part in a lottery with the chance to win one out of fifty tablets.

After a pilot phase in two large hospitals in 2016,Citation22 a country-wide roll-out of OKaPII was performed in autumn 2017. Since 2018, the survey was carried out in spring after the end of each influenza season.

Ethical considerations and Data Protection

The data protection officer of the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) and the Federal commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information in Germany approved the survey. The anonymity of the participants was guaranteed. Individuals had to be at least 18 years to participate in the study. Before the questionnaire started, we obtained an informed consent from all participants via the online questionnaire. For participation in the lottery, e-mail addresses were collected to contact the winners. They were saved separately from the survey data; a connection was not possible.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was designed on the basis of literature research and in consultation with vaccination experts. An English translation of the 2019 questionnaire is provided as appendix (Appendix A).

The questionnaire contained questions about current and previous influenza vaccination status as well as the intention to get vaccinated. In the light of the commitment of the European region to eliminate measles and the priority of the European Vaccine Action Plan to control hepatitis B infection, we decided to include questions on the respective vaccines. In 2018 only, we added questions to assess the participant’s measles vaccination status (vaccination yes/no, number of vaccine doses, and prior natural infection with measles) which were replaced in 2019 by questions related to the hepatitis B vaccination status (vaccination yes/no, number of vaccine doses). In Germany 2 doses of measles vaccine and 3 doses of hepatitis B are recommended for a complete vaccination course. Moreover, reasons for and against receiving the influenza vaccine were assessed. Possible reasons for vaccination (multiple answers possible) were self-protection, patient protection, protection of the personal environment (family and friends), the wish to avoid sickness-related work absences, because it was recommended by others, and other reasons (option to enter a text).

Reasons against the influenza vaccine were designed on the basis of the 3 C-model, which explains vaccine hesitancy with the following determinants ():Citation23

Table 1. Reasons not to get vaccinated, list of items assessed grouped according to vaccine hesitancy model (confidence, complacency, convenience)

Confidence: trust in the safety and effectiveness of vaccines and the institutions recommending them

Complacency: risk perception of vaccine-preventable diseases

Convenience/constraints: physical availability and appeal of immunization services

A systematic review confirmed that these determinants were also relevant for HCW’s influenza vaccination behaviors.Citation24 Possible answers were adapted to the clinical environment and influenza vaccination in particular. Multiple answers were possible.

Sociodemographic information included age, gender, occupation, and work area (e.g. operating room, normal ward etc.). We asked whether participants had direct contact to patients or suffered from chronic diseases and were thus at higher risk.Citation10,Citation25 In addition, we asked whether influenza vaccination was offered at the hospital. Finally, we retrieved data on the hospital size from our contact persons at the participating hospitals. We merged the two data sets.

Statistics

Analysis was conducted with the statistical software R.Citation26 Descriptive statistics were calculated from weighted data; results of regression analyses and totals were not weighted. Data were weighted according to the distribution of occupational groups, gender and hospital size in German hospitals in official data.Citation27 Due to limitations in data availability we did not correct for regional representation and age. We used complete cases analysis since <2.5% of the data were missing. Missing data were not replaced or imputed. We assessed the association of influenza vaccination status and season using chi-squared test.

We performed multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with influenza vaccination status separately for the 2017, 2018 and 2019 data. We decided to analyze the different data sets separately, first because we hypothesized there might be differences from seasons to season and second because a fraction of the hospital staff had participated repeatedly. The dichotomous outcome variable was whether participants were vaccinated against influenza in the respective season (2016/17, 2017/18, 2018/19) or not. We included sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, work area, region), access to the vaccine (offered at workplace or not), hospital size, vaccination status for other vaccines (protection against measles in 2018 data and hepatitis B vaccination status in 2019) and individual risk factors (chronic disease, patient contact) as independent variables (all categorical). All variables were entered at once into the model. We found associations to differ by occupational group (interactions were found between occupational group and age, place of residence as well as work area); moreover, occupational group was associated with influenza vaccination status. Hence, we performed two separate regression analysis for both nurses and physicians. We checked for multicollinearity, calculating the variance inflation factors; values were < 6 for all variables. No variable was hence excluded. We reported Tjur R2 to assess the model fit and reported associations with p < .05 as statistically significant.

Results

Response and Study Population

In total, 52 hospitals participated in the survey in 2017, 125 in 2018 and 171 in 2019. Hospitals were located across Germany. The hospitals had on average 201–500 beds. Over the three seasons, the number of participating hospital staff increased from 5 808 in 2017 to 27 163 in 2019 (). In respect to repeated participation, 10.6% of participants in the 2019 survey indicated that they had participated also in the 2018 or 2017 survey, and 5.3% of the 2018 participants indicated that they had participated also in the 2017 survey. Response rate (i.e. number of survey participants among all employees in the participating hospitals) was around 12% in all seasons.

Table 2. Influenza vaccination coverage and study population stratified for different variables, results from the OKaPII study, data from 2017–2019

The largest groups of participants in all three seasons worked in normal wards or the hospital administration. Around 70% indicated to have contact to patients on a regular basis. Around 90% of all participants reported that the influenza vaccine was offered at their workplace. Notably, around 25% of participants had chronic medical conditions – potentially an additional indication to get vaccinated against influenza. Further details on the study population in all seasons can be found in .

Vaccination Coverage

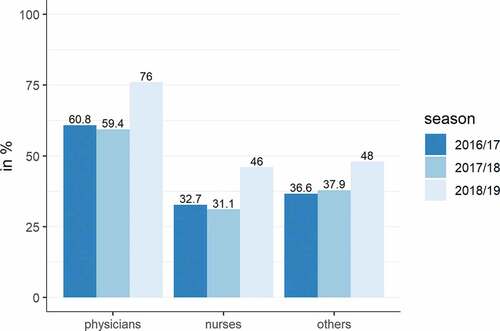

Influenza vaccination coverage among all participants was 39.5% in season 2016/17, 39.3% in season 2017/18 and 52.3% in season 2018/19. Influenza vaccination status was significantly associated with the season (chi-squared test, p < .001). Physicians were significantly more frequently vaccinated than nurses and other professional groups (i.e. all other hospital staff including e.g. administration) (). In 2019, 17.8% of participants reported to have received a flu shot each season over the past five years, 35.1% reported to have not received a flu shot over the past five years (decreasing from 44.0% in 2017). When participants of the 2019 survey were asked about their vaccination intention in season 2019/20, 58.5% intended to get vaccinated against influenza in the upcoming season, 27.7% did not intend to get vaccinated, 13.8% were still unsure. Intention to vaccinate rose from 48.3% in 2017 to 58.5% in 2019. In all survey years, there was a gap between future (intended), and past behavior related to influenza vaccination (10% in 2017 and 2018, 6% in 2019).

Figure 1. Influenza vaccination coverage among German hospital staff in season 2016/17-2018/19. Note: others = all hospital staff that is not physicians or nurses including e.g. administration

In 2018 we assessed measles vaccination coverage. Measles vaccination coverage was significantly higher as compared to the influenza vaccination coverage. We built a subset of all hospital staff <45 years of age, as vaccination is recommended only for adults born after 1970 in Germany.Citation10 Of these, 87.0% reported to have received a measles-virus containing vaccines (54.1% with two, 9.9% with one and 23.0% with an unknown number of vaccine doses) and 6.3% of participants stated to be protected through previous natural infection. Measles vaccination coverage was highest among physicians (91.3%) and their vaccination status was also more often complete with 2 doses (73.5% of physicians claimed to have received two doses of measles vaccine compared 52.2% of nurses).

In 2019 we assessed hepatitis B vaccination coverage among physicians and nurses (as vaccination is not universally recommended to other hospital staff, e.g. in administration).Citation10 Of these, 97.7% reported to be vaccinated against hepatitis B, 2.2% were not vaccinated. Of those vaccinated, 92.0% had received the complete course of 3 doses, 1.6% had an incomplete vaccination course (i.e. 1 or 2 doses) and 4.1% did not know the number of doses received.

Determinants of Influenza Vaccine Uptake

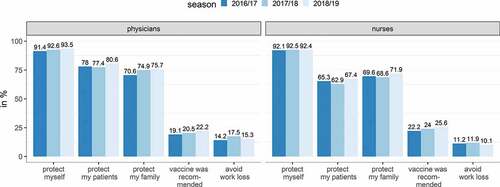

The reasons of being vaccinated against influenza were very similar between occupational groups. The main reason was to protect one’s own health (about 92% for both nurses and physicians in all three seasons), followed by the protection of the personal environment (friends and family) and the protection of patients ().

Figure 2. Reasons for getting vaccinated against influenza among German hospital staff in season 2016/17-2018/19

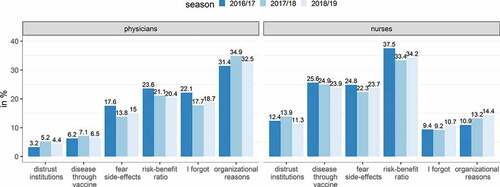

Reasons why participants did not get vaccinated against influenza differed between occupational groups. We selected the four most frequent reasons given by both physicians and nurses and compared them to one another. While both groups frequently named a poor risk-benefit ratio for influenza vaccination, constraints prevailed among physicians (items: “I’ve always wanted to, but for organizational reasons, I’ve not made it” and “I forgot about it/thought about it too late”). Nurses, on the other hand, named primarily reasons related to confidence and misinformation (items: “The influenza vaccine can cause influenza”, “I am afraid of side-effects” and “I do not trust the official recommendations”) ( and ).

Figure 3. Why hospital staff did not get vaccinated against influenza in season 2016/17-2018/19

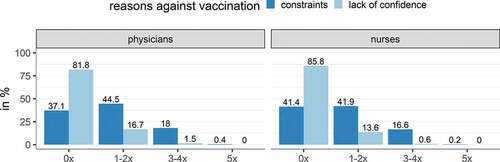

We assessed how participants who gave confidence reasons and participants who gave constraints reasons differed in their previous vaccination behavior. In the 2019 survey, participants who chose confidence as their main reason for not being vaccinated against influenza had received fewer influenza vaccine doses in the past five years than participants who chose constraints reasons (). This was true for both physicians and nurses.

Figure 4. Previous vaccination behavior among unvaccinated hospital staff stratified for occupational group and types of reasons against vaccination (confidence vs. constraints) for 2019 data

shows the results from logistic regression analysis on factors associated with influenza vaccination behavior separately for both nurses and physicians in the 2019 survey. For both physicians and nurses the likelihood of being vaccinated against influenza increased with age, though more pronounced among nurses. An immunization service at the workplace increased the likelihood of being vaccinated. Hospital size had no effect on vaccination status. Both physicians and nurses were more likely to be vaccinated against influenza if they were also protected against measles (via vaccination or natural infection, see Appendix B, 2018 survey) or vaccinated against hepatitis B (see ). In addition, nurses were more likely to be vaccinated if they were working in the eastern part of Germany or suffering from a chronic medical condition. Nurses working in normal wards were less likely to be vaccinated against influenza than nurses in most of the other work areas (ITU, functional diagnostics, ambulance/emergency and administration). In contrast, physicians were more likely to be vaccinated if they had patient contact or were male. In comparison to physicians working in normal ward, those in operating room were less likely and those working in laboratory/logistics more likely to be vaccinated. Regression analyses of the 2017 and 2018 survey data did not reveal any relevant differences in the results (see Appendix B).

Table 3. Factors associated with influenza vaccination status for both nurses and physicians (logistic regressions, 2019 data)

Discussion

With OKaPII a standardized monitoring system of influenza vaccination behavior and motivation has been implemented in German hospitals since 2016. OKaPII can be regarded as successful in that numbers of participating hospitals and individuals increased steadily over three seasons since inception. At the same time the study results for vaccination coverage and motivation, especially for the 2017 and 2018 data, were very similar, which suggests a robustness of our data. Even more so, as the proportion of repeated participation of individuals was small, suggesting that although the majority of hospitals participated repeatedly, different hospital staff were reached.

OKaPII provides insights into behavioral trends in different occupational sub-groups (such as the increase in influenza vaccination coverage among physicians and nurses in 2019) as well as explanations for behaviors (such as the continuous lack of confidence among nurses). These insights can be used to leverage local hospitals in conducting interventions themselves. The OKaPII monitoring system could serve as a model for other countries who aim to implement a simple but robust system to monitor vaccination behavior and motivation among HCW working in hospitals.

Our system identified relevant gaps in influenza vaccination coverage among hospital staff in Germany. Strong differences exist in influenza vaccine uptake among occupational groups, with physicians vaccinated considerably more frequently than nurses. Both the sub-optimal vaccination coverage overall and the differences between occupational groups are in accordance with previous research (though some authors find overall vaccination coverage to be even lower):Citation16 In a national German health study in 2009, which included different HCW (hospital staff and non-hospital staff), vaccination coverage was 29% among physicians and 22% among nurses.Citation15 A similar pattern was found in two sub-national studies from Italy and France.Citation28,Citation29 In a recent German study among family physicians vaccination coverage was 70% in season 2017/18 – 10% higher than among the hospital physicians in the same season in our system.Citation30 Compared to other EU member states, where median vaccination coverage for different HCW (hospital staff and non-hospital staff) was 30% in 2016/17, coverage was 10% higher in the same season in our system.Citation14

We observed an increase in influenza vaccination coverage from season 2017/18 to season 2018/19. This increase was consistent in our data even when stratifying vaccination coverage for e.g. gender, age, or occupational group. While there might be an actual increase in vaccine acceptance over the years, a different explanation has to be considered: The influenza season 2017/18 was unusual, in that it was the most severe influenza season in years. Hospitals were particularly affected with high numbers of hospitalizations.Citation12 In addition, the officially recommended trivalent influenza vaccine had limited effectiveness, as it did not contain the B Yamagata lineage, which proved to be dominant (99% of all influenza B viruses) in this season.Citation12 In January 2018, the STIKO decided to recommend the preferential use of tetravalent influenza vaccines in Germany.Citation31 Hence, when deciding over their next influenza vaccination for the 2018/19 season, hospital staff might have considered that influenza seasons can be quite severe and challenge hospital capacities and that a potentially more effective vaccine is now available. In support of this hypothesis, a slight increase (3–4%) in influenza vaccination coverage was also observed in the general population in Germany.Citation32

Measles vaccination coverage among hospital staff who participated in our survey was below the threshold of 95% recommended for elimination of measles. There is little data on measles vaccination coverage among HCW to verify our results. A serological study in a German university hospital covering data from 2003 to 2013 found 83% of HCW to be protected against measles.Citation33 The measles vaccination coverage among hospital staff aged <45 years in our data was higher than in studies for the German general public: in a nationwide study from 2015 vaccination coverage (at least one dose) was 80% for those 18–29 years and 47% for those 30–39 years.Citation34 With the introduction of a mandatory measles vaccination policy in March 2020, which targets both children and staff in schools and medical institutions, the situation for measles vaccination of hospital staff might be due to change in Germany.Citation35 OKaPII will be utilized to assess measles vaccination coverage and trends as well as vaccine acceptance in the upcoming years to evaluate the effects of this new policy.

In our system, hepatitis B vaccination coverage was high and exceeded influenza and measles vaccination coverage. Nearly all nurses and physicians were vaccinated against hepatitis B. We did not assess data on the 3 Cs related to hepatitis B and measles vaccination. Therefore, exact reasons for the differences in vaccine uptake cannot be provided. Influenza vaccination status was significantly associated with both measles and hepatitis B vaccination status, suggesting hospital staff have some general vaccine-independent heuristic when it comes to decision-making on vaccination behavior.

Hospital staff’s main reason for influenza vaccination was self-protection. Third-party protection was considered less important, especially among nurses. Hospital staff might underestimate the risk of transmitting the virus to their patient.Citation13 Self-protection has been identified as a major reason for vaccination by others as well.Citation36 Reasons against vaccination differed between occupational groups. While physicians were challenged through constraints, nurses showed a lack of confidence and misinformation. Lack of confidence in safety and effectiveness has been identified as one major reason against influenza vaccination in previous studies.Citation36

From our analyses we learn that even though influenza vaccination is universally recommended to all HCW, differences in vaccine uptake exist with regard to sociodemographic and other characteristics: The likelihood of being vaccinated increased with age – HCW have a second indication for vaccination when they are 60+ years –Citation10 and with the availability of immunization services at the workplace. Brewer et al. suggest that on-site vaccination increases seasonal-influenza vaccination. However they qualify this statement as services may be more or less effective depending on whether they create a choice overload or limit choice by setting defaults for vaccination.Citation37 For nurses, working in eastern Germany and suffering from a chronic condition – a second indication for vaccination –Citation10 increased the likelihood of being vaccinated. The regional differences in vaccination coverage have been reported also from previous studies.Citation15,Citation34 For physicians, patient contact and being male increased the likelihood of being vaccinated. Why male physicians would be more likely to be vaccinated than female physicians merits further research. Other studies have shown inconclusive results about gender; gender has been noted both as a barrier and as a promotor to vaccination in previous studies.Citation24

Some limitations of our study need to be acknowledged. The OKaPII study relies on self-report data, hence reported behavior cannot be validated. However, studies have shown high reliability for self-report data in particular for influenza vaccination coverage.Citation38

Our system currently covers around 10% of German hospitals (Germany had 1 942 hospitals in 2017)Citation27 and the response rate on an individual level in the hospitals was relatively low (~12%). This might have led to a selection bias, either encouraging individuals or hospital managements with a strong motivation toward influenza vaccination or perhaps a strong refusal to participate in the survey, affecting both data on vaccine behavior and motivation. However, while increasing the number of hospitals and participating hospital staff more than 3-fold since the inception of the system, the coverage and reasons for/against influenza vaccination remain very stable. This shows, that a subsample of around 5–10% of hospitals in Germany is probably sufficient to monitor trends in vaccination coverage and to obtain some insights into hospital staff’s vaccine confidence and other barriers to vaccination.

We calculated the response rate using the total number of employees in the participating hospitals as a denominator. The total number of e-mail addresses to which the survey-link was sent, could not be assessed, we suppose it is smaller than the total number of employees. Thus, we have probably underestimated the response rate. We evaluated access to professional e-mail and found that some occupational groups have restricted access to e-mail only. We then offered participating clinics to distribute flyers with a QR code to the survey link to enable participation independent of e-mail. We did not conduct a non-responder analysis.

Even though response rate was low, we consider a strength of our systems that this was a nationwide study sample with a large sample size, that study design was simple (keeping the work load of participants low), that the system not only monitors vaccine uptake but also its determinants, and that individual reports on results for the hospitals leverage local action. To further support the implementation of local initiatives, good practice examples on how influenza vaccination coverage was successfully increased among hospital staff was collated in a brochure that was published in 2019 on the OKaPII webpage.Citation39

In conclusion, with OKaPII we established a monitoring system for influenza vaccination behavior and motivation that can both leverage action on a local level in Germany and – as it proved to be robust, simple and well accepted – might serve as a model for implementation in other countries. OKaPII can track behavioral and motivational trends and integrate ad hoc assessments of vaccine uptake and acceptance for other vaccines or policies.

Influenza vaccination coverage among hospital staff is low in Germany, with strong differences in coverage between physicians and nurses. An increase in coverage was observed in 2019, after a severe influenza season and the introduction of the tetravalent influenza vaccine in Germany – which suggests both a temporary change in risk-perception and the better acceptance for a potentially more effective vaccine. In order to increase vaccination coverage, it is crucial to tailor interventions to occupational groups (and potentially to other determinants, in our case age and region). Physicians might benefit from flexible and worksite delivery of vaccines (tackling constraints) whereas nurses might benefit from building trust in both the vaccine and health institution and by offering formal training to counter misinformation.

Abbreviations

| HCW | = | Health-care workers |

| STIKO | = | German Standing Committee on Vaccination |

| OKaPII | = | Online monitoring system on influenza vaccination coverage in German hospitals |

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (40.4 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all colleagues at Robert Koch Institute who were involved in the planning and implementation of the OKaPII study. Our special thanks go to Cornelius Remschmidt and Alexandra Sarah Lang who have been involved in the conception and conduct of the pilot phase.

Declaration of Interest Statement: Sabine Wicker is a member of the German Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO) at Robert Koch Institute in Germany. None of the other authors had any potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at publisher’s website.

References

- Danzmann L, Gastmeier P, Schwab F, Vonberg RP. Health care workers causing large nosocomial outbreaks: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-98.

- Janzen J, Tripatzis I, Wagner U, Schlieter M, ller-Dethard E and Wolters E. Epidemiology of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and antibody to HBsAg in hospital personnel. J Infect Dis. 1978;3:261–65. doi:10.1093/infdis/137.3.261.

- Wicker S, Cinatl J, Berger A, Doerr HW, Gottschalk R, Rabenau HF. Determination of risk of infection with blood-borne pathogens following a needlestick injury in hospital workers. Ann Occup Hyg. 2008;7:615–22.

- Steingart KR, Thomas AR, Dykewicz CA, Redd SC. Transmission of measles virus in healthcare settings during a communitywide outbreak. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;2:115–19. doi:10.1086/501595.

- Miranda AC, Falcao J, Dias JA, Nobrega SD, Rebelo MJ, Pimenta ZP, Saude MD. Measles transmission in health facilities during outbreaks. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;4:843–48. doi:10.1093/ije/23.4.843.

- Lietz J, Westermann C, Nienhaus A, Schablon A. The occupational risk of influenza A (H1N1) infection among healthcare personnel during the 2009 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One. 2016;8:e0162061. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0162061.

- Groenewold MR, Burrer SL, Ahmed F, Uzicanin A, Luckhaupt SE. Health-related workplace absenteeism among full-time workers - United States, 2017-18 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;26:577–82. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6826a1.

- Eibach D, Casalegno JS, Bouscambert M, Bénet T, Regis C, Comte B, Kim BA, Vanhems P, Lina B. Routes of transmission during a nosocomial influenza A(H3N2) outbreak among geriatric patients and healthcare workers. J Hosp Infect. 2014;3:188–93. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2013.11.009.

- Maltezou HC, Botelho-Nevers E, Brantsæter AB, Carlsson RM, Heininger U, Hübschen JM, Josefsdottir KS, Kassianos G, Kyncl J, Ledda C, et al. Vaccination of healthcare personnel in Europe: update to current policies. Vaccine. 2019;52:7576–84. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.061.

- German Standing Commitee on Vaccination. Recommendations of the Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO) at the Robert Koch Institute – 2017/2018. Epid Bull. 2017; 34:333–76.

- Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz. [Law for the prevention of and fight against infectious diseases among humans (German Infection Protection Act - IfSG)] Gesetz zur Verhütung und Bekämpfung von Infektionskrankheiten beim Menschen (Infektscheinsschutzgesetz - IfSG). 2000.

- Buda S, Prahm K, Dürrwald R, Biere B, Schilling J, Buchholz U, An der Heiden M, Haas W [Report on the epidemiology of influenza in Germany, season 2017/18]. Bericht zur Epidemiologie der Influenza in Deutschland, Saison 2017/18. Berlin (Germany): Robert Koch Institute; 2018.

- Ahmed F, Lindley MC, Allred N, Weinbaum CM, Grohskopf L. Effect of influenza vaccination of healthcare personnel on morbidity and mortality among patients: systematic review and grading of evidence. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;1:50–57. doi:10.1093/cid/cit580.

- Mereckiene J. Seasonal influenza vaccination and antiviral use in EU/EEA Member States – overview of vaccine recommendations for 2017–2018 and vaccination coverage rates for 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 influenza seasons. Stockholm (Sweden): European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2018.

- Bohmer MM, Walter D, Muters S, Krause G, Wichmann O. Seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in Germany 2007/2008 and 2008/2009: results from a national health update survey. Vaccine. 2011;27:4492–98. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.039.

- Wicker S, Gottschalk R, Wolff U, Krause G, Rabenau HF. [Influenza vaccination coverage in hospitals in Hesse] Influenzaimpfquoten in hessischen Krankenhäusern. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz. 2012;8:932–36. doi:10.1007/s00103-012-1510-7.

- Hagemeister MH, Stock NK, Ludwig T, Heuschmann P, Vogel U. Self-reported influenza vaccination rates and attitudes towards vaccination among health care workers: results of a survey in a German university hospital. Public Health. 2018;154:102–09. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2017.10.027.

- Buxmann H, Daun A, Wicker S, Schlosser RL. Influenza vaccination rates among parents and health care personnel in a German neonatology department. Vaccines. 2018;1:1–8.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. WHO EpiData. A monthly summary of the epidemiological data on selected vaccine-preventable diseases in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen (Denmark): World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2020. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/427930/2020-01-Epi_Data_EN_January-December-2019.pdf?ua=1

- National Verification Committee for Measles and Rubella elimination in Germany. Annual status update on measles and rubella elimination Germany 2018. (Berlin Germany):National Verification Committee for Measles and Rubella elimination in Germany; 2019.

- World Health Organization. European Vaccine Action Plan 2015-2020; 2014.

- Robert Koch Institute. [Online monitoring system for hospital staff on influenza vaccination coverage (OKaPII)]. Online-Befragung von Klinikpersonal zur Influenza-Impfung (OKaPII-Studie). Epid Bull 2016;47:521–27.

- MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;34:4161–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Schmid P, Rauber D, Betsch C, Lidolt G, Denker ML. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior - A systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005-2016. PLoS One. 2017;1:e0170550.

- Wicker S, Seale H, von Gierke L, Maltezou HC. Vaccination of healthcare personnel: spotlight on groups with underlying conditions. Vaccine. 2014;32(32):4025–31. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.05.070.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Version 3.4.4 [software] ed. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018.

- Statistisches Bundesamt (destatis). [Health. Basic data of the hospitals 2017]. Gesundheit. Grunddaten der Krankenhäuser 2017. Statistisches Bundesamt (destatis); 2018.

- Hulo S, Nuvoli A, Sobaszek A, Salembier-Trichard A. Knowledge and attitudes towards influenza vaccination of health care workers in emergency services. Vaccine. 2017;2:205–07. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.086.

- Rabensteiner A, Buja A, Regele D, Fischer M, Baldo V. Healthcare worker’s attitude to seasonal influenza vaccination in the South Tyrolean province of Italy: barriers and facilitators. Vaccine. 2018;4:535–44. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.007.

- Neufeind J, Betsch C, Habersaat KB, Eckardt M, Schmid P, Wichmann O. Barriers and drivers to adult vaccination among family physicians - Insights for tailoring the immunization program in Germany. Vaccine. 2020;27:4252–62. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.052.

- AG Influenza der Ständigen Impfkommission (STIKO). [Scientific background for the recommendation of the tetravalent seasonal influenza vaccine] Wissenschaftliche Begründung für die Empfehlung des quadrivalenten saisonalen Influenzaimpfstoffs. Epid Bull 2018;2:19–28.

- Rieck T NJ, Feig M, Siedler A, Wichmann O. [Vaccine uptake of adult vaccines from KV-Impfsurveillances data]. Inanspruchnahme von Impfungen bei Erwachsenen aus Daten der KV-Impfsurveillance. Epid Bull. 2019;44:457–66.

- Petersen S, Rabenau HF, Mankertz A, Matysiak-Klose D, Friedrichs I, Wicker S. Immunity against measles among healthcare personnel at the University Hospital Frankfurt, 2003-2013. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;2(2):182–89. doi:10.1007/s00103-014-2098-x.

- Poethko-Muller C, Schmitz R. Vaccination coverage in German adults: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;5-6:845–57.

- Bundesregierung. [Draft of a law for the protection from measles and for the strengthening of prevention through vaccination (Masernschutzgesetz)]. Entwurf eines Gesetzes für den Schutz vor Masern und zur Stärkung der Impfprävention (Masernschutzgesetz); 2019.

- Dini G, Toletone A, Sticchi L, Orsi A, Bragazzi NL, Durando P. Influenza vaccination in healthcare workers: A comprehensive critical appraisal of the literature. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;3:772–89. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1348442.

- Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Rothman AJ, Leask J, Kempe A. Increasing vaccination: Putting psychological science into action. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2017;3(3):149–207. doi:10.1177/1529100618760521.

- Mangtani P, Shah A, Roberts JA. Validation of influenza and pneumococcal vaccine status in adults based on self-report. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;1:139–43. doi:10.1017/S0950268806006479.

- Robert Koch Institute. OKaPII study 2020. [accessed 2020 Mar 15]. Available from: www.rki.de/okapii-studie