ABSTRACT

Introduction

It is unclear what role daughters play in the decision-making process regarding HPV vaccination. Therefore, we explored the impact of HPV vaccination intention among parents and their 12–13 year-old daughters on HPV vaccination uptake.

Methods

In February 2014 parents/guardians and their 12–13 year-old daughters were invited to complete a questionnaire about socio-psychological determinants of the decision-making process regarding HPV vaccination. Vaccination status of the daughter was retrieved from the national vaccination database after the last possible vaccination date in 2014. The association between HPV vaccination uptake and intention, and determinants of intention, was jointly assessed using a generalized structural equation model, stratified by origin of parents (Dutch versus non-Dutch).

Results

In total, 273 Dutch parent-daughter dyads and 165 non-Dutch dyads were analyzed for this study. HPV vaccination uptake was 90% (246/273) and 84% (139/165) in the Dutch and non-Dutch group, respectively. In the Dutch group, high parental intention (β = 2.3, 95%CI 1.2–3.3) and high daughters’ intention (β = 1.5, 95%CI 0.41–2.6) were significantly associated with HPV vaccination uptake. In the non-Dutch group, high daughters’ intention (β = 1.2, 95%CI 0.16–2.2) was significantly associated with HPV vaccination, but high parental intention was not (β = 0.52, 95%CI −0.47–1.5). Attitude was the most prominent socio-psychological determinant associated with vaccination intention among all groups.

Conclusion

In the non-Dutch group, only daughters’ intention was significantly associated with HPV vaccination uptake, whereas in the Dutch group both the parents’ and the daughters’ intention were significantly associated with uptake. The role of the child in the decision-making process might need to be taken into account when developing new interventions focused on increasing HPV vaccination uptake, especially among individuals of non-Dutch origin.

Introduction

Worldwide, human papillomavirus (HPV) causes around 630,000 new cases of cancer each year.Citation1 Since 2006, many countries have introduced prophylactic HPV vaccination,Citation2 but HPV vaccination coverage has remained low.Citation3

In the Netherlands, HPV causes a higher disease burden than any other vaccine-preventable infectious disease.Citation4,Citation5 HPV vaccination was introduced in the Dutch National Immunization Program (NIP) in 2010 and has since been offered free-of-charge to girls during the year of their 13th birthday; based on a tender the bivalent vaccine is being used. In 2014, the vaccination schedule was reduced from three to two doses, in line with guidelines from the European Medicines Agency. Compared to other childhood vaccinations, for which uptake exceeds 90%,Citation6 HPV vaccination uptake is much lower. In 2010, vaccination uptake was only 56% and even though uptake had increased to 61% in 2014, uptake has since decreased to 46% in 2018.Citation6 HPV vaccination uptake is even lower in urban settings (e.g. 36% in Amsterdam in 2018Citation7), and among daughters whose parents are of non-Dutch origin.Citation8,Citation9 Given that the latter group has a higher burden of cervical cancer in comparison to the native Dutch population,Citation10 these individuals could benefit most from HPV vaccination.

Studies exploring the determinants of HPV vaccination intention or uptake have shown that physician’s recommendation, concerns over HPV vaccine safety, and parents’ belief in vaccines are some of the most strongly associated factors of uptake.Citation3 Previous studies in the Netherlands have shown similar determinants, including beliefs regarding HPV vaccination, risk-perception, and subjective norms, but also vaccinating out of habit without active processing of the pro’s and con’s.Citation11–14 Although determinants of uptake did not differ between parents of Dutch and non-Dutch origin (i.e. at least one parent who was not born in the Netherlands),Citation11 these determinants were able to explain HPV vaccination uptake to a greater extent among Dutch parents compared to parents of non-Dutch origin (i.e. the total explained variance of uptake in multivariable analysis was larger in the Dutch group than in the non-Dutch groups).

In our previous study, we found that despite participants having high HPV vaccination intention, this did not always result in HPV vaccination uptake, especially among daughters of parents of non-Dutch origin.Citation11 Shared decision-making between children and their parent(s) on whether to receive HPV vaccination has been previously found to play a role,Citation15,Citation16 and perhaps non-uptake more frequently occurs when parental and daughter HPV vaccination intention are not similar. In the Netherlands, 61% of parents reported that obtaining HPV vaccination was a joint decision.Citation17 However, it is unclear what role daughters play in decisions about HPV vaccination. Studies focusing on this issue have been usually based on the perception of either the daughter or parent and not on unique daughter-parent dyads.Citation18–20

In this study, we explored whether HPV vaccination intention (i.e. willingness to obtain HPV vaccination) of the parent and that of their 12–13 year-old daughter affects actual HPV vaccination uptake, stratified by Dutch and non-Dutch origin. We used data on HPV vaccination intention and its determinants (both socio-psychological and socio-demographic), which were measured before offering HPV vaccination and were independently collected from parents and daughters. These data therefore provide a unique opportunity to explore temporal pathways of the decision-making process concerning HPV vaccination uptake, while simultaneously considering both parental and daughter determinants.

Methods

In the year a girl turns 13 years of age, she is invited for HPV vaccination at a public venue (e.g. sports centers) designated by the Public Health Service at set dates. During vaccination sessions, no personal consultation is given and parental consent is not needed to receive HPV vaccination.

Participants

Selection and invitation procedures for parents/guardians (further referred to as parents) have been previously described in detail.Citation11 In brief, in 2014, all parents with a daughter born in 2001, living in the catchment area of the Youth Health Service of the Public Health Service of Amsterdam, were invited to participate in this study. Parents were invited to participate one month before their daughter’s first scheduled HPV vaccination, i.e. ~2 weeks after receiving an invitation for HPV vaccination. At the end of the parents’ questionnaire, parents were asked whether their daughter could also participate in this study. The daughters received an invitation for a similar (but shorter) questionnaire in the same envelope as their parents. Both parents and daughters received a letter with the questionnaire explaining the purpose of the study. Written informed consent was provided by parents and daughters with the completion and full return of the questionnaire. Parents and daughters were allowed to participate only once. Households with a multiple birth received multiple questionnaires. In analysis, we included only parent-daughter dyads of whom completed questionnaires from both the parent and the daughter were obtained. Incentive for participation was a raffle for one computer tablet. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Center (W2013_257).

Questionnaire

Questions asked were based on a questionnaire developed by Van Keulen et al.Citation13 and were adapted for this multi-ethnic study, as described previously.Citation11 The theoretical framework of the questionnaire was based on the Reasoned Action approach,Citation21 Social Cognitive Theory,Citation22 and the Health Belief Model.Citation23 Daughters and parents received similar questionnaires, apart from questions regarding socio-demographic characteristics, which were not included in the daughter questionnaire.

The parent questionnaire could be completed online or on paper and was available in three languages (Dutch, English and Turkish). The daughter questionnaire was available only online and only in Dutch. In case of an initial non-response of the parent, trained research assistants who spoke at least one other relevant language besides Dutch (i.e. Turkish, Berber, Arabic, English, Spanish, or Twi) called the parents to explain the rationale behind the study and to offer assistance with completing the questionnaire. Research assistants attempted to call parents at most two times. Only HPV-related information that was already provided in the invitation letter for HPV vaccination and the information leaflet for this study was provided to parents. Questions or concerns about HPV vaccination were redirected to the health authorities.

HPV and childhood vaccination uptake and intention

Consent to retrieve their daughter’s vaccination status from the national registry was requested from all parents at the end of the questionnaire. If consent was obtained, the daughter’s HPV and childhood vaccination status was retrieved from Praeventis, the national registry of childhood vaccinations in the Netherlands.Citation24 HPV vaccination uptake was retrieved after the last possible vaccination date in 2014. HPV vaccination uptake was dichotomized as (1) at least one HPV vaccination or (2) no HPV vaccination.

Intention to vaccinate for HPV was assessed in both parents and daughters by asking whether they intended to vaccinate and how likely it was they would get the HPV vaccination. Responses were based on a 5-point Likert score ranging from −2 (low intention) to +2 (high intention). Total intention was a composite score of the two questions (parents’ Cronbach α = 0.96; daughters’ Cronbach α = 0.87).

Determinants of HPV vaccination uptake and intention

Socio-psychological determinants expected to be associated with HPV vaccination uptake and intention have been previously described in detail.Citation11 In brief, determinants involved in the HPV vaccination decision-making process were subdivided into proximal and distal determinants, based on their theoretical cause–effect relationship. Determinants expected to more directly impact parents’ and daughters’ decision are considered “proximal”, whereas those expected to indirectly impact decisions are considered “distal”. All determinants were assessed by multiple questions in the questionnaires (except for risk perception and anticipated regret). Composite scores for these determinants were calculated when the individual items showed sufficient internal consistency (Chronbach’s α > 0.60). Scores were rescaled from −2 to 2, where appropriate. Supplementary Table 1 provides a detailed description of the composite determinants.

Proximal determinants taken into account were: general attitude toward HPV vaccination, HPV vaccination-related beliefs (separated into beliefs related to trust in the government regarding the vaccination and beliefs that the vaccination should only be given once the girl is sexually active), negative outcome expectancies, risk perception, anticipated regret, perceived relative effectiveness of the vaccination, subjective norms (the participant’s perception on what their social environment wanted them to do regarding HPV vaccination and their motivation to comply), descriptive norms (the participant’s expectation of what others would do regarding HPV vaccination), and self-efficacy.

Distal determinants were: knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccination, confidence in authorities, ambivalence about the HPV vaccination, habit strength (vaccinating out of habit without giving it much thought), information processing, amount of information processed, subjective evaluation of the received information, past experience with cervical cancer (self or close relative, evaluated for parents only), and socio-demographic characteristics (parents only).

Socio-demographics consisted of gender, age, highest education level, and religion (in the analysis dichotomized as religious versus non-religious).

Statistical analysis

Ethnicity was defined as Dutch when both parents of the daughter were born in the Netherlands, and as non-Dutch when at least one of the parents was not born in the Netherlands. Socio-demographics, HPV vaccination uptake, childhood vaccination uptake, and HPV vaccination intention were compared between Dutch and non-Dutch participants included in this study.

To understand the decision-making process of the daughter-parent dyads, we constructed a generalized structural equation model (GSEM).Citation25 We chose this modeling approach as we were interested in assessing both (i) the relationship between determinants and HPV vaccination intention and (ii) the interrelationship between determinants of HPV vaccination intention, specific to parents and daughter. We undertook three steps to construct this model: (1) assess the relationship between HPV vaccination intention and HPV vaccination uptake stratified on parents and daughters, (2) assess determinants of HPV vaccination intention stratified on parents and daughters, and (3) using associations from these analyses to inform a GSEM. All analyses described above were stratified by ethnicity (Dutch vs. non-Dutch).

Relationship between HPV vaccination intention and HPV vaccination uptake stratified by parent versus daughter and by Dutch versus non-Dutch origin

The main outcome was HPV vaccination uptake (≥1 dose versus no vaccination). The association between vaccination uptake and vaccination intention was measured using a logistic regression model, wherein vaccination intention was included as a continuous variable. Moreover, we tested for an interaction effect between ethnicity and intention. The marginal probability of HPV vaccine uptake was calculated as a function of vaccination intention from both the daughter and parent, using the ‘margins’ command in Stata,Citation26 which were visualized using heat plots.

Determinants of HPV vaccination intention stratified by parent versus daughter and by Dutch versus non-Dutch origin

As the data did not give rise to homoscedasticity in a linear regression model (i.e. the residuals were not equal across the regression line), we chose to dichotomize intention as high versus intermediate/low intention for further analyses. Odds ratios (OR) comparing the odds of high HPV vaccination intention across levels of proximal and distal determinants, including their 95% confidence intervals (CI), were estimated using bivariable logistic regression.

All variables associated with bivariable analysis (at p < .20, Wald test) were included in multivariable analysis. The multivariable analysis was executed by consecutively adding the proximal determinants, followed by the distal determinants. Stepwise backwards selection was performed before a next set of determinants was added to the model. Variables associated with the outcome variable (p < .05) were kept in the model.

GSEM

Finally, we used the analysis above to inform a GSEM. Paths between parent or daughter vaccination intention and vaccination uptake were kept in the GSEM independent of their statistical level of association. We used the dichotomized variable of intention in the GSEM model since this variable as a continuous measure was not normally distributed. Variables associated with vaccination intention that remained in the multivariable logistic regression model after backwards selection were used as paths to vaccination intention. The expected relationships and inter-relationships between variables were based on the Reasoned Action Approach.Citation21 Outcomes of the GSEM are reported as regression coefficients. Theoretically plausible pathways were tested for significance in the model; pathways that were not significant were removed from the model. A sensitivity analysis was done, in which all non-normally distributed, significant determinants of intention were dichotomized to assess whether the strength of the associations was influenced by distribution assumptions.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 15.1; StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Response rate

In total, parents of 4,216 daughters born in 2001 were invited to participate in the study. Of the 1,362 (33%) parents who completed and returned the questionnaire,Citation11 650 daughters also returned the questionnaire (16% of all invited daughters; 48% of all daughters whose parents participated). Of the returned daughter questionnaires, 462/650 (71%) daughter respondents had parental consent to participate. Of the 462 parent-daughter dyads, 461 (99.8%) returned the questionnaire before the first scheduled date of HPV vaccination. Twenty-three dyads were excluded from analysis because the parent did not give permission to verify vaccination status of their daughter (n = 17) or the questions regarding intention to vaccinate were not answered (n = 5) or a large proportion of questions was left unanswered (n = 1). This resulted in 438 daughter-parent dyads being analyzed (Supplementary Figure 1).

Baseline characteristics

Of the 438 parent-daughter dyads, 273 dyads (62%) were of Dutch origin and 165 (38%) of non-Dutch origin (in 86% of these, both parents were of non-Dutch origin). Among the non-Dutch participants, 34 (21%) were of Surinamese, Netherlands Antillean, or Aruban origin, 58 (35%) of Middle Eastern and North African origin and 73 (44%) from another origin (e.g. Sub-Saharan Africa or Asia). The majority of parents were female (90%), median age was 45 years (inter quartile range [IQR] 42–48) and 29% had had higher education. Dutch parents were older than parents of non-Dutch origin (p < .001) and were more often highly educated (p < .001). Among Dutch parents, the majority was not religious (73%), while in the non-Dutch group, 25% were not religious.

HPV vaccination intention of parents was high for both Dutch (median 2, [IQR] 1–2) and parents of non-Dutch origin (median 2, [IQR] 1–2). Although the median and the IQR were the same, there was still a significant difference in the overall distribution (i.e. overall the values were higher for the Dutch parents, p = .013). Median HPV vaccination intention of the daughters was also high for both Dutch (median 1.5, [IQR] 1–2) and non-Dutch daughters (median 1.5, [IQR] 1–2); there was no significant difference in the overall distribution (p = .146). There was no difference in HPV vaccination intention between non-Dutch daughters of whom both parents were of non-Dutch origin and non-Dutch daughters of whom only one parent was of non-Dutch origin (p = .415).

HPV vaccination uptake was higher among Dutch girls, 90% of whom received at least one vaccination, compared to non-Dutch girls (84%), although not significantly (p = .068). There was no difference in HPV vaccination uptake between non-Dutch daughters of whom both parents were of non-Dutch origin and non-Dutch daughters of whom only one parent was of non-Dutch origin (p = .858). Overall, past childhood vaccination uptake was 97% among Dutch girls and 93% among non-Dutch girls (p = .059) ().

Table 1. Baseline socio-demographic characteristics of the parents/guardians of 12–13 year-old girls, HPV-vaccination intention, actual childhood vaccination and HPV vaccination uptake, stratified by country of birth of parents; HPV vaccination acceptability study in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2014

Relationship between HPV vaccination intention and HPV vaccination uptake stratified by parent versus daughter and by Dutch versus non-Dutch origin

HPV vaccination intention was positively associated with HPV vaccination uptake in both Dutch and non-Dutch parents and daughters (). The OR of HPV vaccination intention in relation to HPV vaccination uptake (i.e. the odds to be vaccinated per 1 point increase on the 5-point Likert scale of intention) was 7.55 (95% CI 3.98–14.32) among the Dutch parents and 4.87 (95% CI 2.97–8.01) among the Dutch daughters. In the non-Dutch dyads, the OR of vaccination intention was 2.54 (95% CI 1.68–3.85) among parents and 3.79 (95% CI 2.28–6.30) among their daughters. The effect of intention on vaccination uptake was significantly less strong in the parents of non-Dutch origin compared to the Dutch parents (xOR 0.34, 95% CI 0.16–0.72, p = .005). There was no difference in effect of daughter’s intention on vaccination uptake between ethnicities (xOR 0.78, 95% CI 0.34–1.58, p = .486).

Table 2. Association between HPV vaccination intention and vaccination uptake of 12–13 year-old daughters and their parents stratified by ethnicity. HPV vaccination acceptability in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2014

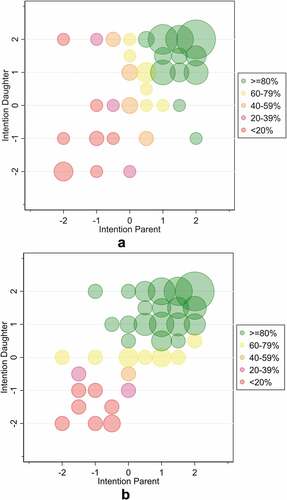

To visualize the granularity of these associations, a heat map was generated wherein intention of the parents is depicted on the x-axis, intention of the daughter is depicted on the y-axis, and the color of the circle indicates the proportion of daughters who were vaccinated corresponding to a given combination ( for Dutch and for non-Dutch dyads). Circle size is proportional to the number of parent-daughter dyads for a given combination of intentions, while non-observed combinations were omitted from the graph. In Dutch dyads, the intention of both the parent and daughter was directly proportional to vaccine uptake. In non-Dutch dyads, the intention of the daughter alone was directly proportional to vaccine uptake; vaccination uptake was >80% for all girls with intention ≥1.5, regardless of parental intention.

Figure 1. Heat map of the marginal prediction of HPV vaccination uptake corresponding to each combination of HPV vaccination intention among parents and their daughters. (a). Dutch parent-daughter dyads. (b). Non-Dutch parent-daughter dyads. Circle size is proportional to the number of parent-daughter dyads for a given combination of intentions; non-observed combinations were omitted from the graph. The color of the circle indicates that ≥80% (green), 60–79% (yellow), 40–59% (orange), 20–39% (pink) or <20% (red) of daughters for a given combination were vaccinated against HPV

Determinants of HPV vaccination intention stratified by parent versus daughter and by Dutch versus non-Dutch origin

For the selection of determinants associated with HPV vaccination intention at p < .20 that were included in the multivariable analysis, see Supplementary Table 2. In multivariable analysis, determinants associated with HPV vaccination intention of the Dutch parents were (Supplementary Table 3): attitude (p < .001), beliefs related to trust (p = .168), beliefs related to sexual activity (p = .063), descriptive norms (p = .019), habit strength (p < .001) and past experiences with (pre-stage of) cervical cancer (p = .048). The following were associated with HPV vaccination intention of the Dutch daughters: attitude (p < .001), anticipated regret (p = .006), descriptive norms (p = .057) and ambivalence (p = .012).

The following determinants were associated with HPV vaccination intention of parents of non-Dutch origin in multivariable analysis: attitude (p = .001), beliefs related to trust (p = .116), subjective norms (p = .017) and habit strength (p = .004). Determinants associated with HPV vaccination intention of the non-Dutch daughters were: attitude (p < .001), subjective norms (p = .036) and descriptive norms (p = .030). These variables were further considered in the GSEM.

GSEM among Dutch parent-daughter dyads

The final GSEM among Dutch parent-daughter dyads is presented in . Factors directly significantly associated with HPV vaccination uptake were high intention of the parent (β = 2.29, 95% CI 1.22–3.36, p < .001) and the daughter (β = 1.48, 95% CI 0.41–2.57, p = .007). Factors directly associated with HPV vaccination intention of the parents were attitude and descriptive norms. Factors indirectly associated with HPV vaccination intention of the parents were habit strength, beliefs related to trust, and beliefs related to sexual activity. As past experience with cervical cancer was not significantly associated with attitude (p = .28) in the GSEM, this pathway was removed from the final model.

Figure 2. Generalized structural equation model including determinants of the intention of parents and daughters associated with HPV vaccination uptake. 2a. Dutch parent-daughter dyads. 2b. Non-Dutch parent-daughter dyads. The numbers next to each pathway indicate the regression coefficient (β) and the 95% confidence interval. ε indicates the random error component within the individual regression models. In the Dutch GSEM: the pathway between attitude and past experiences with cervical cancer was removed from the model as it was not significant

Factors directly associated with HPV vaccination intention of the daughters were attitude and descriptive norms. Factors indirectly associated with HPV vaccination intention were anticipated regret and ambivalence.

Sensitivity analysis in which dichotomized variables of all non-normally distributed determinants were included (i.e. attitude, descriptive norms, beliefs related to sex, habit strength, anticipated regret and ambivalence) yielded similar, although stronger effect sizes (data not shown).

GSEM among non-Dutch parent-daughter dyads

The final GSEM among non-Dutch parent-daughter dyads is presented in . Factors directly correlated with HPV vaccination uptake were intention of the parent and the daughter. The association of high intention with uptake was significant for daughters’ intention (β = 1.19, 95% CI 0.16–2.22, p = .023), but not for parents’ intention (β = 0.52, 95% CI −0.47–1.52, p = .299). Factors directly associated with vaccination intention of the parents were attitude and subjective norms. Factors indirectly associated with HPV vaccination intention were beliefs related to trust and habit strength.

Factors directly associated with vaccination intention of the daughters were attitude, subjective norms, and descriptive norms.

Sensitivity analysis in which dichotomized variables of all non-normal determinants were included (i.e. attitude, descriptive norms and habit strength) yielded again similar, although stronger effect sizes (data not shown).

Discussion

We found that in Dutch parent-daughter dyads, intention of both the parents and the daughters played an important role in the decision to vaccinate against HPV. However, in non-Dutch parent-daughter dyads, we found that the intention of the daughter played a more important role than the intention of the parent. Factors directly influencing HPV vaccination intention were (i) attitude and (ii) subjective and descriptive norms. Factors indirectly influencing HPV vaccination intention were (i) beliefs related to trust in the government regarding HPV vaccination and to timing of HPV vaccination after sexual debut, (ii) habit strength (vaccinating out of habit without giving much thought), (iii) anticipated regret if rejecting HPV vaccination, and (iv) ambivalence (i.e. both positive and negative feelings) toward HPV vaccination.

Decision-making process

Although the decision to vaccinate against HPV is highly contextual (i.e., clinic or school based, opt-in or opt-out consent, parent and/or daughter consent), there is always some level of involvement from the parent and their child(ren).Citation15,Citation16,Citation27,Citation28 Indeed, studies have reported that >50% of the time, the child (and/or their partner) was involved in the decision.Citation15,Citation16 In contrast, from cross-sectional studies based on parent-child dyads using a qualitative approach, parents and children did not report similarly on which person actually makes the decision to vaccinate.Citation18–20 Further quantitative research on parent-son dyads found that parental beliefs about HPV vaccination weighed more importantly in the decision-making process than those of their son.Citation29 Another cross-sectional study among parent-child dyads showed that each member of the dyad was able to estimate how their preference differed from the other family member.Citation30 Age of the child can also influence which member is deciding to vaccinate, particularly for daughters.Citation27

In our longitudinal study, the intention of the daughter and parent was collected before the daughter received HPV vaccination, and their vaccination status was retrieved from the National Database a couple of months after the last opportunity to receive the second HPV vaccination dose. With this design, we were able to measure a temporal association between intention and actual behavior. We found that the intention of both the parent and the daughter were significantly associated with HPV vaccination uptake in both the Dutch and non-Dutch groups. Yet in the non-Dutch group, the intention of the daughter was more strongly associated with actual HPV vaccination uptake than that of their parents.

Although self-efficacy concerning how information is processed and the amount of information processed was not a significant predictor of HPV vaccination intention, it is possible there might be a (perceived) language barrier among parents of non-Dutch origin. In a study among Cambodian-American daughter-mother dyads living in the US, for instance, 26% of mothers thought that because their daughter received education in English, the daughter had more health-related knowledge than them.Citation31 Unfortunately, we were unable to provide a complete explanation for the Dutch versus non-Dutch difference observed in the association between intention and behavior of mothers and daughters. Although little is known about how the health literacy of adolescents impacts their healthcare decisions,Citation32,Citation33 better proficiency in Dutch of non-Dutch daughters in relation to their parents may have positively influenced the daughters’ intention to vaccinate against HPV. Further research is needed to confirm these results.

The implications of these results are not straightforward for policymakers in the Netherlands. The Health Council of the Netherlands advised to lower the age of HPV vaccination to 9 years-old and to include boys,Citation34 which will take effect in 2021. Studies have shown that the age of the child influences parental opinion on whether to involve the child in the decision-making process.Citation16,Citation27 We showed that 13 year-old daughters in the non-Dutch group seemed to have a positive influence on HPV vaccination uptake and similar HPV vaccination intention as their Dutch peers. However, when vaccination age is lowered to 9 years-old, increasing HPV vaccination intention among parents of non-Dutch origin might become of key importance.

Determinants of HPV vaccination uptake and intention

Attitude was the main driver of intention for Dutch and non-Dutch parents and daughters, which is in line with other international studies.Citation3 Consistent with previous Dutch studies,Citation12–14,Citation35 we found that attitude, beliefs, social norms, and habit strength were significantly associated with intention to vaccinate against HPV in both Dutch and non-Dutch parents, but general knowledge concerning the HPV vaccination was not. Knowledge overall was high in this study population, leading to little variation between participants, which might explain the absence of a relationship between knowledge ad intention.Citation13 The belief focusing on trust in the government, pharmaceutical industry and proven safety of the vaccine was significant, as expected.Citation36–38 The Dutch government has made considerable efforts in offering balanced information concerning HPV vaccination. However, HPV vaccination is currently offered by means of group-based HPV vaccination in public venues, without opportunities for parent or child to have a personal conversation with a professional; this could affect uptake. Participation at these vaccination venues probably involves parents who are intent on vaccinating their daughters. The fact that we found habit strength to be an important predictor among parents of both Dutch and non-Dutch origin, but not among daughters, suggests HPV vaccination engages little thoughtCitation39 and is based on previous experience with, and decisions about, other childhood vaccinations.Citation12,Citation13 Social environment (e.g. subjective and descriptive norms) was significantly associated with intention, consistent with previous Dutch studies.Citation12,Citation13 Finally, in our previous analyses of overall determinants of HPV vaccination intention among parents, we observed that these did not differ significantly between ethnicities.Citation11 Here we show that girls may play a more prominent role in the decision-making process in families of non-Dutch origin. As HPV vaccination uptake disparities between ethnic groups have been observed in the Netherlands,Citation8,Citation9 it is important to take the role of daughters, and potentially sons when vaccination is also offered to boys, into account in this decision-making process.

Strengths and limitations

One strength of this study is its longitudinal nature, enabling us to use confirmed HPV vaccination uptake as an outcome, rather than solely vaccination intention or self-reported vaccine status. Second, anticipating illiteracy and language barriers in our study population, we offered the parent questionnaire in three languages (Dutch, English and Turkish) and offered assistance with the questionnaire by telephone in six languages to increase participation. Yet, despite thorough training of the assistants, there may have been a possibility that the assistance given by telephone influenced participant answers. Last, using GSEM, we could assess not only parental and daughter determinants simultaneously but also measure how effects between variables relate within the same model. Having data of both parents and daughters gives a unique insight into the decision-making process among parent-daughter dyads.

One limitation of our study is that despite efforts to recruit a large and ethnically diverse population of parents and daughters, we could only include 438 parent-daughter dyads in this analysis; this group represents 10.4% of all eligible parent-daughter dyads, the majority of whom were Dutch. This restricted our analyses of parents from non-Dutch origin, rendering it difficult to further stratify for different ethnic groups. Secondly, HPV vaccination uptake in our study population was higher (83%) than the overall HPV vaccination uptake in Amsterdam in 2014 (44%),Citation7 indicating that study participants were not representative of the general population. Third, we had a limited number of individuals with low intention, limiting the power of our analyses and thus more subtle associations might have been missed. Fourth, as vaccination intention and some of the determinants for intention did not meet the assumption of homoscedasticity for linear regression and normal distribution for GSEM, these variables had to be dichotomized. Due to low numbers of participants with low intention to vaccinate, we had to combine participants with low and intermediate intention. This may have influenced the observed effect sizes and reduced the power needed to observe statistically significant differences; associations may actually be stronger than shown here and some important determinants may have been missed.

Conclusion

In Dutch parent-daughter dyads, intention of both the parents and the daughters played an important role in the decision to vaccinate against HPV. In the non-Dutch parent-daughter dyads, intention of the daughters was the main driver of HPV vaccination uptake. Studies focusing on ethnic disparities should take into account the role of the child when exploring determinants of HPV vaccination uptake. Additionally, the role of the child in the decision-making process might need to be taken into account when developing new interventions focused on increasing HPV vaccination uptake, especially among individuals of non-Dutch origin.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Author’s contributions

CJA, MFSL, MPe, MPr, VW, AN, HM and TP contributed to the study design. CJA contributed to the data collection. VJ, CJA, AB and MFSL contributed to the analysis and/or interpretation of the analyses. VJ drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version for publication.

Disclaimer

Where authors are identified as personnel of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (125.2 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all parents/guardians and their daughters for participating in this study. Additionally, we would like to thank the research assistants who assisted in gathering the data for this study, the data managers, and Yvonne Hazeveld and Fatima El Fakiri (GGD Amsterdam), members of the HP4V advisory group. We would like to thank Susan Gamon for proof reading the manuscript.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1808411.

Additional information

Funding

References

- de Martel C, Plummer M, Vignat J, Franceschi S. Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:664–70. doi:10.1002/ijc.30716.

- Bruni L, Diaz M, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, Herrero R, Bray F, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Castellsagué X. Global estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage by region and income level: a pooled analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2016;4(7):e453–e63. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30099-7.

- Newman PA, Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Baiden P, Tepjan S, Rubincam C, Doukas N, Asey F. Parents’ uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines for their children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019206. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019206.

- van Lier A, McDonald SA, Bouwknegt M, Kretzschmar ME, Havelaar AH, Mangen MJJ, Wallinga J, de Melker HE. Disease burden of 32 infectious diseases in the Netherlands, 2007-2011. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153106. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153106.

- McDonald SA, Qendri V, Berkhof J, de Melker HE, Bogaards JA. Disease burden of human papillomavirus infection in the Netherlands, 1989-2014: the gap between females and males is diminishing. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28:203–14. doi:10.1007/s10552-017-0870-6.

- van Lier EA, Oomen PJ, Giesbers H, van Vliet JA, Drijfhout IH, Zonnenberg-Hoff IF, de Melker HE. Vaccinatiegraad en jaarverslag. Rijksvaccinatieprogramma Nederland 2018, RIVM rapport. Bilthoven, the Netherlands: RIVM; 2019

- Volksgezondheidenzorg.info. Grafiek HPV-vaccinatie per gemeente. RIVM, ed.; 2019. https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info/onderwerp/vaccinaties/regionaal-internationaal/adolescenten#node-hpv-vaccinaties-gemeente.

- Rondy M, van Lier A, van de Kassteele J, Rust L, de Melker H. Determinants for HPV vaccine uptake in the Netherlands: A multilevel study. Vaccine. 2010;28:2070–75. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.042.

- Schurink- van ‘T Klooster T, De Munter A, Van Lier A, Ruijs H, De Melker H. Determinants of HPV-vaccination coverage over time in the Netherlands. Abstract #0500. EUROGIN, Monaco, 2019.

- Arnold M, Razum O, Coebergh J-W. Cancer risk diversity in non-western migrants to Europe: an overview of the literature. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2647–59. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.050.

- Alberts CJ, van der Loeff MF, Hazeveld Y, de Melker HE, van der Wal MF, Nielen A, El Fakiri F, Prins M, Paulussen TGWM. A longitudinal study on determinants of HPV vaccination uptake in parents/guardians from different ethnic backgrounds in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):220. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4091-4.

- Pot M, van Keulen HM, Ruiter RAC, Eekhout I, Mollema L, Paulussen T. Motivational and contextual determinants of HPV-vaccination uptake: A longitudinal study among mothers of girls invited for the HPV-vaccination. Prev Med. 2017;100:41–49. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.005.

- van Keulen HM, Otten W, Ruiter RAC, Fekkes M, van Steenbergen J, Dusseldorp E, Paulussen TW. Determinants of HPV vaccination intentions among Dutch girls and their mothers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):111. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-111.

- Hofman R, van Empelen P, Richardus JH, de Kok IM, de Koning HJ, van Ballegooijen M, Korfage IJ. Predictors of HPV vaccination uptake: a longitudinal study among parents. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(1):83–96. doi:10.1093/her/cyt092.

- Berenson AB, Laz TH, Hirth JM, McGrath CJ, Rahman M. Effect of the decision-making process in the family on HPV vaccination rates among adolescents 9-17 years of age. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:1807–11. doi:10.4161/hv.28779.

- Perez S, Restle H, Naz A, Tatar O, Shapiro GK, Rosberger Z. Parents’ involvement in the human papillomavirus vaccination decision for their sons. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2017;14:33–39. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2017.08.005.

- van Lier EA, Geraedts JLE, Oomen PJ, Giesbers H, van Vliet JA, Drijfhout IH, Zonnenberg-Hoff IF, de Melker, HE. Vaccinatiegraad en jaarverslag Rijksvaccinatieprogramma Nederland 2017, RIVM rapport. Bilthoven, the Netherlands: RIVM; 2018

- Chang J, Ipp LS, de Roche AM, Catallozzi M, Breitkopf CR, Rosenthal SL. Adolescent-parent dyad descriptions of the decision to start the HPV vaccine series. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2018;31:28–32. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2017.10.003.

- Griffioen AM, Glynn S, Mullins TK, Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL, Fortenberry JD, Kahn JA. Perspectives on decision making about human papillomavirus vaccination among 11- to 12-year-old girls and their mothers. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51:560–68. doi:10.1177/0009922812443732.

- Morales-Campos DY, Markham CM, Peskin MF, Fernandez ME. Hispanic mothers’ and high school girls’ perceptions of cervical cancer, human papilloma virus, and the human papilloma virus vaccine. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:S69–75. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.020.

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior. New York: Psychology Press; 2010. doi:10.4324/9780203838020

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. New York: Prentice Hall; 1986.

- Becker MH. The health belief model and sick role behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:409–19. doi:10.1177/109019817400200407.

- van Lier A, Oomen P, de Hoogh P, Drijfhout I, Elsinghorst B, Kemmeren J, Conyn-van Spaendonck M, de Melker H. Præventis, the immunisation register of the Netherlands: a tool to evaluate the national immunisation programme. Eurosurveillance. 2012;17(17):20153. doi:10.2807/ese.17.17.20153-en.

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A, Pickles A. Generalized multilevel structural equation modeling. Psychometrika. 2004;69:167–90. doi:10.1007/BF02295939.

- Williams R. Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J. 2012;12:308–31. doi:10.1177/1536867X1201200209.

- McRee AL, Reiter PL, Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT. Mother-daughter communication about HPV vaccine. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:314–17. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.006.

- Lefevre H, Samain S, Ibrahim N, Fourmaux C, Tonelli A, Rouget S, Mimoun E, Tournemire RD, Devernay M, Moro MR. HPV vaccination and sexual health in France: empowering girls to decide. Vaccine. 2019;37:1792–98. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.02.020.

- Moss JL, Reiter PL, Brewer NT. HPV vaccine for teen boys: dyadic analysis of parents’ and sons’ beliefs and willingness. Prev Med. 2015;78:65–71. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.002.

- Vietri JT, Chapman GB, Li M, Galvani AP. Preferences for HPV vaccination in parent-child dyads: similarities and acknowledged differences. Prev Med. 2011;52:405–06. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.03.002.

- Lee H, Kim D, Kiang PN, Cooley ME, Shi L, Thiem L, Kan P, Chea P, Allison J, Kim M. Awareness, knowledge, social norms, and vaccination intentions among Khmer mother-daughter pairs. Ethn Health. 2018;1–13. doi:10.1080/13557858.2018.1514455.

- Santos MG, Gorukanti AL, Jurkunas LM, Handley MA. The health literacy of U.S. immigrant adolescents: A neglected research priority in a changing world. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15. doi:10.3390/ijerph15102108.

- Orellana M, Dorner L, Pulido L. Accessing assets: immigrant youth’s work as family translators or “para-phrasers.”. Soc Probl. 2003;50:505–24. doi:10.1525/sp.2003.50.4.505.

- Gezondheidsraad. Vaccinatie tegen HPV. Den Haag, the Netherlands: Gezondheidsraad; 2019.

- Paulussen TG, Hoekstra F, Lanting CI, Buijs GB, Hirasing RA. Determinants of Dutch parents’ decisions to vaccinate their child. Vaccine. 2006;24:644–51. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.053.

- Rodriguez SA, Mullen PD, Lopez DM, Savas LS, Fernandez ME. Factors associated with adolescent HPV vaccination in the U.S.: A systematic review of reviews and multilevel framework to inform intervention development. Prev Med. 2020;131:105968. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105968.

- Kessels SJ, Marshall HS, Watson M, Braunack-Mayer AJ, Reuzel R, Tooher RL. Factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake in teenage girls: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;30:3546–56. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.063.

- Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45:107–14. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.013.

- Shapiro GK, Tatar O, Amsel R, Prue G, Zimet GD, Knauper B, Rosberger Z. Using an integrated conceptual framework to investigate parents‘ HPV vaccine decision for their daughters and sons. Prev Med. 2018;116:203–10. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.09.017.