ABSTRACT

Introduction: Young adults may be facing growing threats from vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs). However, vaccination of young adults may not have drawn adequate attention. In Asia, adensely populated region with ahigh proportion of low-income countries, VPDs impose more of an economic and social burden than in western countries. However, knowledge about attitudes toward vaccines among young Asians is limited. This study aims to fill that gap by describing attitudes toward vaccines and how well they are accepted among young Asian adults through asystematic review of relevant Chinese and English publications.

Methods: A three-stage searching strategy was adopted to identify eligible studies published during 2009–2019 according to the selection criteria, resulting in 68 articles being included.

Results: The review finds that vaccination coverage among young Asians is generally lower than among their western peers, and there is a lack of relevant study in many Asian countries. Factors influencing young Asians’ attitudes toward vaccines are categorized into contextual level, individual and social level, and vaccine-specific level.

Conclusion: These suggest that there is a need to strengthen young adults’ vaccination programs and to promote vaccine-related information and government.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

As one of the greatest public health intervention strategy in the world, vaccination can prevent 2–3 million deaths from vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) annually.Citation1 Globally, children have routinely been prioritized in immunization programs.Citation2,Citation3 The progress in children’s immunization in the past decades has also changed the epidemiology of some VPDs with higher prevalence in other age groups.Citation4 Actually, vaccination of young adults is challenging, especially in most low and middle income countries (LMICs).Citation4

Young adults may be at risk of VPDs due to their age, inadequate immunization, lifestyle, job and health condition. They are more likely to be infected with some VPDs, because their immune systems aren’t fully developed yet. Moreover, they may not be adequately immunized in their childhood.Citation5 Currently, still approximately 18.7 million babies (nearly one-fifth children) worldwide are not routinely immunized with vaccines against VPDs such as diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus.Citation1 When they grow up, some viruses or pathogens may continue to spread among them, due to insufficient childhood vaccination coverage or uneven coverage among geographical regions.Citation6 Some countries have launched supplementary vaccination programs. However, population immunization coverage may be lower than the need for herd immunity to specific VPD. For example, China conducted a nationwide Hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) supplemental immunization activity, but studies found that the coverage (≥1 dose) is just around 50% among young Chinese adults.Citation7–12 Young adults also have unique health risks. First, as most of them are still in college/university, or just start their career, they have much close social contact, including sharing classrooms, dormitories, dining spaces and bathrooms, which imposes particular risks of VPDs on them.Citation13,Citation14 Second, they are more likely to have sex than children and adolescents, but not always protect themselves by using condoms.Citation15 Therefore, they face higher risk of sexually transmitted diseases or viruses, such as Hepatitis B and Human Papillomavirus (HPV).Citation15 In addition, some young adults are at even higher risk because of their jobs or health conditions. For example, as recommended by the WHO, health workers and pregnant women are the priority groups to receive certain vaccination.Citation16

More than half of the world’s population live in Asia,Citation17 where less-developed countries account for a big share.Citation18 Studies have indicated that the death burden from infectious diseases in low-income region is much greater than in high-income areas.Citation19 For example, 88% deaths from cervical cancer occur in developing countries.Citation20 Nearly a fourth of influenza LRTIs (lower respiratory tract infections) death are in India and China.Citation21 Asia is the region with the highest rate of HBsAg carriers, and chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has brought huge social and economic burden to the world.Citation22 As Hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) was introduced to most of South-East Asia countries in 1990s or 2000s,Citation23 a number of local young adults above 20 may not be vaccinated against HBV in their childhood. Moreover, the sexual concept of young Asian adults has changed greatly, leading to first sexual intercourse at younger age and more people with multiple sexual partners, which exposes them to huge potential health risks.Citation24

However, limited studies show that vaccine coverage among Asian young adults is low or just suboptimal. For instance, a systematic review capturing relevant studies from 2008 to2018 indicated that influenza vaccination rates among general people in different Asian countries were about 0.8%~45% (the median is just 14.9%),Citation25 while it was more than 40% during 2010 ~ 2016 among all people ≥6 months in the United States.Citation26 The rate among healthcare workers (HCWs) in recent years have been over 75% in America,Citation27 much higher than that in Asia (the median is just 37.6% among HCWs).Citation25 Studies also indicated that only about 10% of young Asians received the HPV, much lower than that in some developed countries such as Canada (65%),Citation28 Australia (86%),Citation29 the United Kingdom (71%),Citation30–33 and the United States (64%).Citation34

However, the general and systematic information regarding vaccine coverage among Asian young adults is limited. Ramesh argued that, adult immunization is becoming the most neglected part of healthcare system in India.Citation2 There have been a lot of studies on children’s vaccination. Researchers also have increasingly paid much attention to other age groups such as the elderly, and most studies come from western countries. But there is no systematic review on the attitudes of young Asians toward vaccination. The study is to understand more about the attitude of young adults toward VPDs and vaccination in the context of Asia, a region remarkably different from others in sociocultural background, family and social norms, as well as religion.Citation35 To be specific, the review aims to draw a comprehensive picture about vaccination among Asian young adults: (1) reviewing and descriptively analyzing the attitudes of young Asians toward vaccination; and (2) diving into influencing factors behind their attitudes.

Methodology

Search strategy

To review the attitudes of young Asians toward vaccination comprehensively and systematically, a three-stage search strategy was adopted to select both qualitative and quantitative literature for the review from January 2009 to December 2019. First, based on the methodology of SheldenkarCitation25 and Larson,Citation36 three groups of search terms were listed: (1) term group 1 (TG1) aimed to search for literature related to vaccination; (2) term group 2 (TG2) aimed to find out literature related to young adults; and (3) term group 3 (TG3) aimed to identify literature related to attitude and awareness toward vaccine/vaccination. Title searches were used: Search1: Title included any terms in TG1 and any terms in TG2; Search2: Title included any terms in TG1 and any terms in TG3(see ).

Then, the literature was searched on ELSEVIER Science Direct (SDOS), Pubmed, and Web of Science that were available in the author’s library. The Chinese literature was searched on China Knowledge Network (CNKI), Wanfang Database and VIP Database. Finally, the references of included papers were scanned to find additional articles which may not been captured by the database search. Endnote X6 was used to manage the literature search process. And the duplicates were removed.

Selection criteria

Selection criteria was developed based on the methodology in Sheldenkar’s study.Citation25 Eligible literature should be studies published in English or Chinese between January 2009 and December 2019, and focusing on young Asians’ attitude, views, willingness and awareness of their own vaccination.

There are several important concepts to emphasize in this study: (1) in broad sense, someone’s attitude to vaccination also include that to vaccination of others, such as attitude to children’s vaccination as parents or toward patients’ vaccination as doctors. In order to stay focused, this study only discusses participants’ attitude toward their own vaccination; (2) young adults refer to people aged 18–24 by WHO standards.Citation37 It is noted that population covered by this study may go beyond this age range. For example, target population of HPV vaccination is those from 9 to 45 years old. The study also discusses influenza vaccination of pregnant women, regardless of their age, as the WHO recommends that they are prioritized, and most of them are young adult. In addition, when a study covers both young adults and other age groups, it is included in the review only if vaccination status and attitude of the former group are reported separately.

Studies focusing mainly on vaccination of children or elderly are excluded. So are the studies on the United States, Europe, Africa, and the non-Asian Middle East countries; those on vaccine efficacy and production, gray literature, correspondence, review, editorials. Chinese literature published on journals outside the Catalog of Chinese Core Periodicals of Peking University Library (commonly recognized by Chinese scholars) is not eligible. Studies on the attitude to others’ vaccination, such as parents’ attitude to their children’s vaccination were also excluded.

Data extraction and coding

The retrieved papers were screened by title and abstract according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. One author (LY) extracted data from included researches, and another author (WL) checked the extracted information with full text of each papers, to ensure the accuracy. The authors resolved the disagreement on literature selection and data extraction after discussions.

The main aim of the data extraction process was to capture the corresponding participants’: (1) current vaccination status; (2) vaccination attitude/intention (positive or negative); (3) the level of awareness/knowledge about VPDs/vaccine; (4) influencing factors which were coded into three levels using SAGE WG Model,Citation35 contextual level, individual/social level and vaccine and vaccination-specific level.

Results

Identified literature

Endnote X6 was used to process all identified studies, the duplicates were removed, and 5016 left. Then, one researcher (LY) screened them by the titles and abstracts to remove ineligible articles (N = 4579), and retained 439. Two researchers (WL and YJ) read the full text of all the articles left, of which 390 were excluded because they did not meet the criteria and 49 left. To identify maximum eligible literature, two researchers (YJ and WL) did intermittent search on Google Scholar, tracked references of the 49 studies, and found another 19 eligible papers (see ).

68 independent studies from 12 countries/regions in Asia are included. Most studies are from mainland China (N = 19), followed by Hong Kong (N = 10)(Hong Kong is a city in China. However we want to discuss Hong Kong separately in this study, because its different social system from mainland China, named “one country two systems.” Actually, we found that about one third of included studies in China (N = 29) were about Hong Kong (N = 10). Therefore, we think that it may make sense to discuss Hong Kong separately), South Korea (N = 9), Japan (N = 8), Malaysia (N = 4), Pakistan (3), India (N = 3), Singapore (N = 2), Vietnam (N = 2), Bangladesh (N = 2), Nepal (N = 2), Taiwan (N = 2), and Thailand (N = 2). Of them, there are more studies from East Asia than Southeast Asia and South Asia. In general, there is a lack of scientific research on young adults’ attitudes toward vaccination in most Asian countries.

Of the 68 articles, most are about HPV vaccine (N = 28) and influenza vaccines (including seasonal influenza vaccines and H1N1 influenza vaccines, N = 21 and 5, respectively), followed by HepB (N = 6). Few studies focus on vaccination of measles, cholera, rubella, pertussis, and related public attitudes. Other vaccines are less discussed (see ). Two studies are about multiple vaccines.

Table 1. Number of included studies by country/area and vaccine

Attitude to and awareness of vaccines

HPV vaccine

In total, 22,798 participants were covered by the 28 selected studies. Twenty-five of them used quantitative questionnaires and 3 in-depth qualitative interviews. Vaccination rates were reported in 13 studies and attitude/awareness/knowledge/willingness was analyzed in 26 articles.

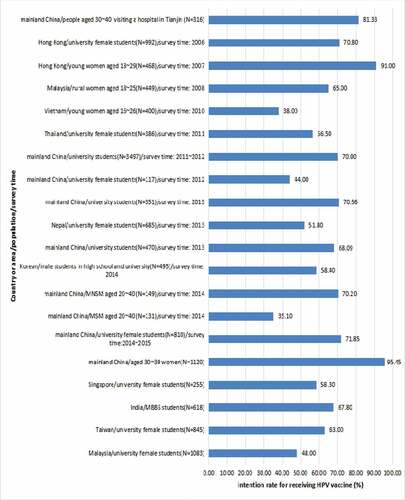

Of them, a Japanese study involving 5,924 female participants registered the highest HPV vaccination rate (16.9%), but it did not touch on the participants’ attitudes toward the vaccine.Citation38 The second highest coverage rate (13.3%) was from a study in Hong Kong.Citation39 In others, the vaccination rates were below 10%.Citation40–45 Twenty studies described the awareness rate of HPV or HPV vaccine among the participants or whether they were willing to vaccinate. In general, HPV awareness was low. For example, three studies in China showed that only about 10% of respondents had heard of HPV and HPV vaccines.Citation46–48 In a study targeting female sex workers who are always in high risk for HPV infection, only 23.6% of 220 respondents had heard of HPV.Citation49 However, the 20 studies describing willingness of HPV vaccination showed that high percentage of respondents intended to be vaccinated against HPV, ranging from 38% (Vietnamese participants) to 95.45% (Chinese participants). In 17 of them, the percentage was higher than 50% (see ).

According to included studies surveying awareness of HPV/HPV vaccines by using the Likert scale or questionnaire, the awareness is generally low. For example, a study in Singapore conducted a questionnaire survey to evaluate and grade the participants’ knowledge on cervical cancer and HPV vaccine. The knowledge was found to be at low level, with a median of 7 (score range: 0 ~ 14).Citation39 In a study in Malaysia, participants only got an average score of 3.25 out of 14.Citation50 Two studies in South Korea found that the average score in willingness to receive HPV vaccine was suboptimal among participants.Citation51,Citation52 Another South Korean study found that participants got an average score of 2.18 ± 0.53 in their HPV-related knowledge and health beliefs (the total knowledge score ranged from 0 to 4).Citation53 However, as the above studies might adopt different survey tool and scoring methods, the results may not be comparable.

Influenza vaccine

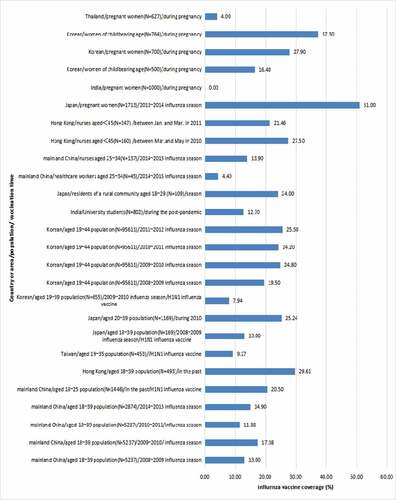

Asia, covering multiple climatic regions, has long been considered as an important source of influenza viruses. In some places, an epidemic of influenza virus exists all year round. However, coverage of influenza vaccine among Asians is low (only about 10%).Citation18,Citation54 A total of 26 included articles discussed vaccination against seasonal influenza or H1N1 influenza among young adults in mainland China, Hong Kong, Korea, Japan, India, Pakistan, Taiwan, and Thailand. According to WHO recommendations, pregnant women and HCWs are prioritized vaccination groups. Of the articles identified in this review, six studies investigated women’s attitudes toward influenza vaccination during their pregnancy; and four were about flu-vaccination-related attitudes and behaviors among HCWs. Another 14 studies reported the flu vaccination status of general population and their attitudes (including college students). Two of them surveyed participants’ vaccination status of influenza in different influenza seasons.

The authors extracted related data by regions/populations/seasons from the above mentioned literature (see ). In general, influenza vaccine coverage was low, ranging from 0 to 51%. In 14 of included studies, the rate was below 20%. However, most of studies, in which influenza vaccine coverage of participants was higher than 20% were about pregnant women or HCWs such as nurses or doctors. It is noted that there were significant differences in influenza vaccination rate among pregnant women in different countries. In all included studies, the highest influenza vaccine coverage (51%) came from a survey of pregnant Japanese women, while the lowest rate(0) was from India(see ).

Hepatitis B vaccine

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a serious global public health threat, and the virus can be transmitted through blood, sexual intercourse and other routes.Citation55 People with frequent exposure to viral blood (such as HCWs) and those who regularly engage in unprotected sexual intercourse are always in high potential infection risk. The latter group should pay more attention to this issue in particular, as young Asian adults’ sexuality attitude are changing, leading to dramatic increase in unprotected sexual behaviors.Citation15 But only nine included studies discussed attitudes toward HBV and HepB among young Asians. Most of them (N = 6) were from China, four of which were quantitative studies and two qualitative ones. HepB coverage among Chinese young adults was not high. The rate of at least one dose of HepB was about 55.33%–74.6%.Citation11,Citation56,Citation57 HCWs were found higher study attention and greater acceptance of HepB in included studies. Three of six chinese studies analyzed hepatitis B vaccination among HCWs (including medical students). One qualitative study on vaccination of medical students (types of vaccines were not specific) in China indicated that participants had discussed HepB more frequently than other vaccines in focuse group interview, and most of them has received HepB before or during their internship (or could provide evidence to prove their immunity to hepatitis B).Citation58 A study in Nepal found that the majority (86.5%) of medical students were vaccinated against Hepatitis B, of which 83.7% received a complete course of HepB.Citation59 However, a study in Laos found that the HepB coverage among young HCWs was not high.Citation60 Only 61.1% of the 587 HCWs aged 20–25 received HepB.

Other vaccines

Included studies about other vaccines are very limited. Only six of the included studies described attitudes to other vaccines, including two on measles vaccine, two on cholera vaccine, one on pertussis vaccine, and one on rubella vaccine. It is indicated that these vaccines are not received adequately, and participants have limited knowledge about relevant VPDs/vaccines. For example, a study in South Korean surveyed vaccination against measles among nursing students found that 52.5% of the 380 participants got measle-containing vaccine. However, more than 70% had never been educated about measles. That may explain why the average score of a quiz on measles and measles vaccine was only 52.68 ± 19.94 (score range: 0 ~ 100). However, most of the participants in those studies were willing to be vaccinated against relevant VPD. Take a study in Pakistan for example, it focused on the pertussis vaccination of 283 pregnant women participants, 53% of them had never heard of pertussis, but 75.61% were willing to vaccinate.Citation61

Factors influencing vaccination and attitudes to it

Globally, vaccination is influenced by vaccine hesitancy which is considered one of the top ten global health threats in 2019.Citation36 SAGE working group identified three levels of factors behind vaccination and attitudes to it, namely, contextual level, individual and social level, and vaccine and vaccination specific issues. This framework was adopted in this study to analyze factors influencing young Asian adults’ vaccination and their attitudes to it.

HPV vaccine

Contextual factors

Contextual factors that affect participants’ HPV vaccination include socioeconomic and demographic variables such as age, education, income, marital status, characteristics of work, study or workplace, accessibility of the vaccine, and availability of relevant information. Of them, the availability of relevant information and education is discussed the most frequently. As one included study in India showed, the significant challenge of an HPV vaccination program was inadequate information.Citation62 Cultural factor also matters. According to some included studies in MalaysiaCitation63 and Thailand,Citation45 many participants were reluctant to get HPV vaccination because they thought it was embarrassing to talk about sexual behaviors, HPV or related vaccines. Family decisions are also important. Concerns on potential objection from parentsCitation43 or lack of their supportCitation64,Citation65 is one of the major obstacles to get HPV vaccine (see ).

Table 2. Factors(promoters/P or barriers/B) relevant with HPV vaccine attitude

Individual and social factors

Individual health beliefs about HPV, HPV vaccines (perception of the risk and severity of the disease, etc.) and related knowledge are critical to people’s attitudes to the vaccine. In some countries, concern about the adverse effects of HPV vaccine is an important barrier. For instance, after the HPV vaccine was first approved for clinical use in Japan in 2009, vaccination rate among target young girls was high, close to 70%–80%. However, the rate decreased significantly, after a report on the side effects of the vaccine was published in 2013. In Sakai, Osaka, the vaccination rate among school-age girls dropped from about 70%–3.9%.Citation38 In addition, the characteristics of sexual behavior and experience, advice from others, previous vaccination experience, etc., and family history of gynecological diseases are also important influencing factors. It is noted that sexual behavior and experience does not influence vaccine attitude in only one direction. For example, several included studies indicated that participants with sexual experience and multiple sexual partners were more willing to receive vaccination. A study on HPV vaccination among men showed that those who had anal sex, unprotected sex, or had sex with prostitutes were more willing to get HPV vaccination. However, in other studies, some participants without any sex experience were reluctant to get vaccinated, because they did not think they were at high risk(see ).

Vaccine and vaccination specific issues

Financial costs of vaccination was identified widely as a significant barrier. Two studies in mainland China showed that for most participants the highest acceptable price of the vaccine was 300 yuan for a complete course of HPV vaccine, but it is actually about 2000–3000 yuan.Citation47 A study in South Korea showed that 77.8% of respondents thought HPV vaccination was expensive, as the price for the full course ranged from 420 USD to 520, USD while the average monthly salary in South Korea was only 1792.65 USD In other studies in Singapore, South Korea, China, etc., price of the vaccine was also seen as one of the key barriers(see ).Citation39,Citation40,Citation56,Citation63,Citation66,Citation67

Influenza vaccine

At contextual level, participant’s education level presents a mixed set of results regarding vaccination behavior or attitude toward influenza vaccine. Studies about mainland China have shown that vaccination rate is higher among poorly educated young adults,Citation67,Citation68 whereas studies about Hong Kong indicated that among pregnant women, bachelor’s degree holders were less willing to get the vaccination than those with higher degrees.Citation69 Vaccination policy is regarded as one of important contextual influencing factors. A study about Pakistan indicated that absence of compulsory vaccination policy was a key barrier for HCWs’ vaccination.Citation70 At the level of individual and social factors, perception of the influenza infection risk and effectiveness of the influenza vaccine are still identified as strong influencing factors. For example, three included studies have shown that influenza vaccines are not well accepted by medical students, partly because they do not think flu is a serious condition.Citation69 Studies about Korean pregnant women showed that worrying about potential risk of influenza vaccine for their babies is also a significant barrier,Citation71 and being advised by professionals was an important promoter to receive influenza vaccine.Citation72 In the general population, studies about KoreaCitation73 and TokyoCitation74 found that underlying health behaviors (such as physical checkups tobacco or alcohol use) also affect their vaccination behaviors (see ).

Table 3. Factors (promoters/P or barriers/B) relevant with participants’ attitude toward influenza vaccine

Hepatitis B vaccine

At contextual level, after discussing information availability, vaccination organization, and vaccination accessibility in medical schools in detail, Wang Li’s qualitative study found a major negative factor that schools failed to provide students with sufficient information and vaccination activities.Citation58 Studies about China and Laos found that another barrier was not knowing where to receive vaccination.Citation60,Citation72 At individual level, Studies about China found that the more college students know about hepatitis B or HepB, the more likely they are to be vaccinated against HepB.Citation11,Citation55,Citation58,Citation75 At vaccine-specific level, because the complete course of HepB needs multiple shots, the participants are reluctant or easily forget to vaccinate.Citation58

Discussion

This study may be the first systematic review of young Asian adults’ attitudes toward vaccines. It systematically reviews the literature on young Asians’ attitudes to vaccination and related influencing factors. Existing studies mainly focus on HPV and influenza vaccines, with limited attention to those against hepatitis B, measles and rubella. In many Asian countries, there is little research on vaccination of young adults against those diseases. Limited literature indicated that relevant vaccine coverage among young adults are low or just sub-optimal in Asia. The finding are consistent with Bruni L’s study which reported that the HPV vaccination rate among Asians aged 10–20 is only 1.1%, and that of all age groups is 0.2%.Citation76 In most of included literature about influenza vaccination, the coverage among participants are below 20%, and it is relatively higher in high-risk groups such as pregnant women and HCWs. Similarly, a retrospective study found that influenza vaccination rates among Asian adults was low, ranging from 0.8% to 45%, with a median of 14.3%, and the median of high-risk group was about 37%.Citation58 Globally, influenza vaccines are less accepted than other vaccines. Its coverage is particularly low in developing countries.Citation72 Pregnant women are seen as high-risk population for some VPDs such as influenza. Limited included studies on pregnant women’s behavior and attitude toward influenza vaccine showed that in some Asian countries like Japan and South Korea, their vaccine coverage is similar to their western peers. Around 20% pregnant women are vaccinated against influenza in the United StatesCitation77 and the United Kingdom.Citation78 That means the influenza vaccine acceptance among pregnant group is not encouraging globally. SaitohCitation79,Citation80 showed that vaccination education can positively influence maternal attitudes about infant vaccination. Maybe some contents about vaccinating pregnant-women themselves can be added in these education programs.

Many included studies on vaccination against hepatitis B are from China, probably because Chinese is one of the two selected languages in the literature search. Though HepB was introduced to China’s national EPI in 2002, the vaccination was not free of charge until 2005. Therefore, some young Chinese adults did not receive HepB in their childhood. According to some studies, many young Chinese do not remember whether they have been vaccinated against hepatitis B. This study finds that the HepB coverage among Chinese college students is just slightly higher than 50%. The rate among young Chinese adults is much lower than their peers in Western countries.Citation81 In the included literature, there are just small number of studies on HepB vaccination in Asian adults, which may indicate that Asian governments, general population and experts have not paid enough attention to the topic.

Only several studies discussed vaccination against measles, rubella, cholera and pertussis among young Asian adults and their attitudes to those vaccines. One of them found that the measles vaccination rate among Korean nursing students was not high.Citation82 Despite of fluctuation in recent years, the incidence of measles in most countries/regions is still much higher than the WHO’s recommendation, one case per million population.Citation83 Even in developed countries, there have been some measles outbreaks in recent years.Citation84 It is noted that in case of some VPDs such as measlesCitation33 or pertussis,Citation81,Citation85 adult patients are more likely than children to have severe conditions causing hospitalization, complications, or death.Citation86 So it is urgent to conduct more scientific research in this area.

Another feature of this study is that the influencing factors are divided into contextual, individual and social, and vaccine-specific level based on WHO SAGE Model, which not only presents the reasons behind young Asian adults’ attitudes to vaccine more comprehensively, but also compares relevant studies internationally.

At contextual level, the attitude of young Asian adults is mainly influenced by vaccination policy, local culture, ethnically/religious factors, and situation regarding health education of vaccine and VPDs. Firstly, in term of vaccination policy, most vaccines discussed in this study are not covered by their national immunization programs. So the relevant vaccination is neither free nor compulsory, which impacts accessibility and people’s attitude. In China, most vaccination for people above 6 is on voluntary basis and paid out-of-pocket, which was seen as an important reason for a low vaccine coverage. In Japan, low coverage of some vaccines which were out of the routine childhood vaccination schedule were also explained as a consequence of voluntary vaccination.Citation87 In South KoreaCitation73 and JapanCitation74 government provides free or partially subsidized influenza vaccination to elderly people, children, pregnant women, health workers and those with underlying diseases. Among young adults who are not covered by the policy, the vaccination rate is only about 20%.Citation73,Citation88 China and Lao recommend health workers to receive HepB, but do not provide the service free of charge. Therefore, the vaccination rate among health workers is relatively low-around 50% in ChinaCitation7 and 21% in Lao.Citation60 We argue that purely “voluntary”/“out-of-pocket” policy may cause vaccination inequity. For example, Zhou indicated that, in China, household income was an important factor influencing parents’ knowledge, awareness and intention about HPV vaccination.Citation89 Therefore it is suggested that actions be taken to disseminete information about vaccination, or cover it in the benefit package of health insurance. Especially for some expensive vaccine like HPV vaccine whose coverage is quiet low in most Asian countries.

Secondly, at cultural level, for example, embarrassment about premarital sex and sexually transmitted diseases is found to be a significant barrier of HPV vaccination. Ethnically/religious factors were mentioned by just a few included studies (for instance, one from MalaysiaCitation50 and one from Nepal),Citation90 the topic was also discussed in other existing literature about parents’ attitude to their children vaccination,Citation91,Citation92 and the Westerners’ attitude to their own HPV vaccination.Citation93,Citation94 Most of the studies imply lower awareness of relevant vaccines and lower acceptability of the vaccination among minority group.

Thirdly, health education factors matter significantly. Two included studies about Korea showed that, 98% and 70% of participants, had never received any education on HPV or measles vaccines.Citation53,Citation82 That means young adults have difficulty receiving vaccine-related education, while vaccination education showed positively influence people’s attitudes and beliefs in vaccination.Citation79,Citation80 Effective education and awareness campaigns can also reduce concerns about vaccination safety and vaccine hesitation and mitigate the impact of cultural factors, which may result in positive influences on vaccination.Citation58 Therefore, at the contextual level, a comprehensive and systematic vaccination plan or program which considers various influences of cultural, policy, ethnically/religious dimension, and health education, was needed urgently.

From individual and social relations perspective, individual perceptions about VPDs and vaccination such as VPDs’ risk and severity, vaccine effectiveness and possible side effect, vaccination barriers and so on, as well as social norms about vaccination may affect people’s vaccination behaviors and attitudes. It is noteworthy that concerns on safety and side effects were identified as barriers in several included studies.Citation62,Citation64 However, children’s vaccination is influenced greatly by their parents’ attitude toward vaccine safety and reliability.Citation95 It may show that there is a comparably better vaccine confidence among young Asian adults about their own vaccination, but this inference may not be accurate because of the limited number of included literature. The review showed that individual sexual experience,Citation53,Citation75 having multiple sexual partners,Citation90 and individual health behaviors such as physical examination, physical exercise, tobacco and/or alcohol use, etc., may be associated with attitudes to vaccines. The influences of sex experience and situation of sexual partners on individual’s behavior and attitude toward HPV vaccine are also discussed in studies about western countries. For example, not being sexually active was found the main reason for not receiving HPV vaccine in American young adults aged between 18 and 26 years old.Citation93 It is noteworthy that the influences of individual’s health behaviors including physical exercise, tobacco/alcohol use on vaccination as mentioned in some included studies is less discussed deeply and specifically by researchers at present, which may point out a new study direction in this area. This study found that social factors including recommendations from others,Citation51,Citation52 objection from parents and other interactions between individual and society were seen as important promoters or barriers to adult vaccination.Citation96 This findings are also consistent with results from other population such as elderlyCitation97 and adolescents.Citation98

At vaccine-specific level, this study seem to suggest that vaccine cost may be an important barrier for public’s acceptability for some expensive vaccine like HPV vaccine. HPV vaccine is not included in government immunization programs in most Asian countries (e.g., Korea,Citation51 China,Citation47 etc.). In the future, government subsidy in Asian countries should be considered to mitigate the negative impact of high price on HPV vaccination. Other factors at vaccine/vaccination specific level including vaccination schedule, mode of administration, mode of delivery, reliability of vaccine supply, role of health-care professionals are less mentioned in included articles. It may suggest that studies on the topic are still very limited, and calls for more attention from scholars.

In addition, one of important findings of this review is that young Asian adults are strongly willing to vaccinate though they have very limited knowledge about VPDs and vaccines. For example, over 50% of the participants are willing to vaccinate against HPV. This provides a good foundation for the implementation of potential vaccination program. With financial support (such as free vaccination policy or reimbursement by public health insurance), more accessible vaccination service effective information dissemination and health education by Asian countries and governments, the willingness will be translated into vaccination behaviors. Despite of higher coverage than Asia, western countries have shown significant vaccine hesitancy in recent years.Citation36 However, young Asians have not yet fallen into the modern paradox of distrusting vaccine while enjoying health benefits of immunization. It may be a great chance to prevent vaccine hesitancy in Asia.

There are several limitations in the study. (1) Considering time and difficulty of translating various languages, the study only includes articles either in English or in Chinese. The literature covered in this review varies in terms of participants and design, so some information is not comparable. However, we still analyzed the highlighted factors influencing vaccine attitude of Asian young adults. (2) This study includes much literature about college students. It is undeniable that this group account for a large part of young people. However, this target group is usually selected for convenience of study, and may not be representative of all young people. (3) Several researchers searched literature by multiple search terms in parallel and pooled the results together to maximize eligible literature. But as this review covers many Asian countries and several vaccines, it may be inevitable that some eligible literature were missed in the review.

Conclusion

This study analyzes attitudes of young Asian adults to vaccines and their vaccination behaviors by literature review. Most existing studies focus on vaccination against HPV and influenza. Many Asian countries lack scientific research on other vaccines. Analysis shows that it is urgently needed to provide information on vaccine, organize education campaigns on vaccination, implement vaccination programs for young adults, introduce government subsidies, and conduct more research in this area so as to increase vaccination rate among young Asian adults.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

List of abbreviations

| VPDs | = | Vaccine-preventable diseases |

| LICs | = | Low-income countries |

| HPV | = | Human papilloma virus |

| HBV | = | Hepatitis B virus |

| HepB | = | Hepatitis B vaccine |

| MMR | = | Measles, mumps, and rubella conjugate vaccine |

| NIP | = | National Immunization Program |

| EPI | = | Expanded Program on Immunization |

Availability of data and materials

Data can be made available by request.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Anhui Medical University.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World immunization week 2016: immunization game-changers should be the norm worldwide; 2016 April 21 [accessed 2019 Sept 20]. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/detail/21-04-2016-world-immunization-week-2016-immunization-game-changers-should-be-the-norm-worldwide.

- Verma R, Khanna P, Chawla S. Adult immunization in India: importance and recommendations. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(9):2180–82. PMID:25483654. doi:10.4161/hv.29342.

- Mehta B, Chawla S, Kumar V, Jindal H, Bhatt B. Adult immunization: the need to address. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(2):306–09. PMID:24128707. doi:10.4161/hv.26797.

- Lahariya C, Bhardwaj P, Adult vaccination in India: status and the way forward. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;1–3. PMID:31743073. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1692564.

- Lang PO, Govind S, Michel JP, Aspinall R, Mitchell WA. Immunosenescence implications for vaccination programmes in adults. Maturitas. 2011;68(4):322–30. PMID:21316879. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.01.011.

- Kanitz EE, Wu LA, Giambi C, Strikas RA, Levy-Bruhl D, Stefanoff P, Mereckiene J, Appelgren E, D’Ancona F. Variation in adult vaccination policies across Europe: an overview from Venice network on vaccine recommendations, funding and coverage. Vaccine. 2012;30(35):5222–28. PMID:22721901. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.012.

- Gao Y, Li Y, Teng H, Liu D, Chen D. Investigation of the knowledge, attitude and practice related to hepatitis B among students in a medical university in Nanning. Ying Yong Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi(in Chinese). 2016;22:486–549.

- Yuan Q. Hepatitis B virus status and vaccination coverage among health care workers in three provinces of China. Chinese Certer for Disease Control and Prevention (In Chinese). 2018:1-69.

- Ma B, Wang Y, Ma H, Jiang Y, Liu P, Zhao H, Liu J. Analysis of hepatitis B vaccination rate and influencing factors among college students in Lanzhou. Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Jiao Yu Za Zhi (in Chinese). 2014;32(3):126–27.

- Wu X, Zhou N, Sun C, Zhi Q, Wang Y, Li S. Prevalence and influencing factors of hepatitis B vaccination among college students in Yucheng City of Shandong province. Zhong Guo Gong Gong Wei Sheng Za Zhi (In Chinese). 2018;34:1282–84.

- Mei L. Analysis on the influencing factors of hepatitis B vaccine inoculation rate in college students. Zhong Guo Xiao Yi Za Zhi(in Chinese). 2015;29:768–69.

- Yan X, Zhu H, Qin Y, Yang X, Wen X. Influence factors analysis in vaccination rate of hepatitis B vaccine in college students. Zhong Guo Shi Yong Yi Yao Za Zhi (In Chinese). 2015;10:240–42.

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Clinical management of human infection with new influenza A(H1N1) virus: initial guidance; 2009 [accessed 2011 July 13]. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/clinical managementH1N121May2009.pdf.

- Kumar A, Murray DL, Havlichek DH. Immunizations for the college student: a campus perspective of an outbreak and national and international considerations. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52(1):229–41. PMID: 15748933. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2004.10.009.

- Ozer EM, Urquhart JT, Brindis CD, Park MJ, Irwin CE Jr. Young adult preventive health care guidelines there but can’t be found. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(3):240–47. PMID:22393182. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.794.

- WHO. Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper—November 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87(47):461–76. PMID:23210147.

- Gerland P, Raftery AE, Sevčíková H, Li N, Gu D, Spoorenberg T, Alkema L, Fosdick BK, Chunn J, Lalic N, et al. World population stabilization unlikely this century. Science. 2014;346(6206):234–37. PMID:25301627. doi:10.1126/science.1257469.

- Jennings LC. Influenza vaccines: an Asia–Pacific perspective. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(Suppl 3):44–51. PMID:24215381. doi:10.1111/irv.12180.

- Oshitani H, Kamigaki T, Suzuki A. Major issues and challenges of influenza pandemic preparedness in developing countries. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(6):875–80. PMID:18507896. doi:10.3201/eid1406.070839.

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–917. PMID: 21351269. doi:10.1002/ijc.25516.

- Troeger CE, Blacker BF, Khalil IA, Zimsen SRM, Albertson SB, Abate D, Abdela J, Adhikari TB, Aghayan SA, Agrawal S; GBD 2017. Influenza collaborators. Mortality, morbidity, and hospitalisations due to influenza lower respiratory tract infections, 2017: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(1):69–89. PMID: 30553848. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30496-X.

- Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C, Vos T, Abubakar I, Abu-Raddad LJ, Assadi R, Bhala N, Cowie B, et al. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2016;388:1081–88. PMID:27394647. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30579-7.

- Childs L, Roesel S, Tohme RA. Status and progress of hepatitis B control through vaccination in the South-East Asia region, 1992–2015. Vaccine. 2018;36(1):6–14. PMID: 29174317. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.11.027.

- Lee SY, Lee HJ, Kim TK, Lee SG, Park EC. Sexually transmitted infections and first sexual intercourse age in adolescents: the nationwide retrospective cross-sectional study. J Sex Med. 2015;12(12):2313–23. PMID: 26685982. doi:10.1111/jsm.13071.

- Sheldenkar A, Lim F, Yung CF, Lwin MO. Acceptance and uptake of influenza vaccines in Asia: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2019;37(35):4896–905. PMID:31301918. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.011.

- USA CDC. Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2016–17 influenza season. [accessed 2019 July 18]. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1617estimates.htm.

- Black CL, Yue X, Ball SW, Donahue SM, Izrael D, de Perio MA, Laney AS, Williams WW, Lindley MC, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among health care personnel - United States, 2015–16 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(38):1026–31. PMID: 30260944. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6738a2.

- Ogilvie G, Anderson M, Marra F, McNeil S, Pielak K, Dawar M, McIvor M, Ehlen T, Dobson S, Money D, et al. A population-based evaluation of a publicly funded, school-based HPV vaccine program in British Columbia, Canada: parental factors associated with HPV vaccine receipt. PLoS Med. 2010;7(5):e1000270. PMID:20454567. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000270.

- Agius PA, Pitts MK, Smith AMA, Mitchell A. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer: gardasil vaccination status and knowledge amongst a nationally representative sample of Australian secondary school students. Vaccine. 2010;28(27):4416–22. PMID:20434543. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.038.

- Brabin L, Roberts SA, Stretch R, Baxter D, Chambers G, Kitchener H, McCann R. Uptake of first two doses of human papillomavirus vaccine by adolescent schoolgirls in Manchester: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7652):1056–58. PMID:18436917. doi:10.1136/bmj.39541.534109.BE.

- Roberts SA, Brabin L, Stretch R, Baxter D, Elton P, Kitchener H, McCann R. Human papillomavirus vaccination and social inequality: results from a prospective cohortstudy. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139(3):400–05. PMID:20334731. doi:10.1017/S095026881000066X.

- Brabin L, Roberts SA, Stretch R, Baxter D, Elton P, Kitchener H, McCann R. A survey of adolescent experiences of human papillomavirus vaccination in the Manchester study. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(9):1502–04. PMID:19809431. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605362.

- Stretch R, Roberts SA, McCann R, Baxter D, Chambers G, Kitchener H, Brabin L. Parental attitudes and information needs in an adolescent HPV vaccination programme. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(11):1908–11. PMID:18985038. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604766.

- Dempsey AF, Abraham LM, Dalton V, Ruffin M. Understanding the reasons why mothers do or do not have their adolescent daughters vaccinated against human papillomavirus. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(8):531–38. PMID:19394865. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.011.

- Wong LP, Wong PF, MMAA MH, Han L, Lin Y, Hu Z, Zhao Q, Zimet GD. Multidimensional social and cultural norms influencing HPV vaccine hesitancy in Asia. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(7):1611–22. PMID: 32429731. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1756670.

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DM, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150–59. PMID:24598724. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081.

- WHO. Global accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation. [accessed 2020 Apr 27]. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/framework-accelerated-action/en/.[2020-04-27](2020-04-27).

- Sawada M, Ueda Y, Yagi A, Morimoto A, Nakae R, Kakubari R, Abe H, Egawa-Takata T, Iwamiya T, Matsuzaki S. HPV vaccination in Japan: results of a 3-year follow-up survey of obstetricians and gynecologists regarding their opinions toward the vaccine. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23(1):121–25. PMID:28986659. doi:10.1007/s10147-017-1188-9.

- Zhang QY, Wong RX, Chen WM, Guo XX. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding human papillomavirus vaccination among young women attending a tertiary institution in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2016;57(6):329–33. PMID:27353611. doi:10.11622/smedj.2016108.

- Hsu YY, Fetzer SJ, Hsu KF, Chang YY, Huang CP, Chou CY. Intention to obtain human papillomavirus vaccination among taiwanese undergraduate women. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(11):686–92. PMID:1965262. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181ad28d3.

- Lee A, Ho M, Cheung CK, Keung VM. Factors influencing adolescent girls’ decision in initiation for human papillomavirus vaccination: a cross-sectional study in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:925. PMID:25195604. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-925.

- Juntasopeepun P, Davidson PM, Suwan N, Phianmongkhol Y, Srisomboon J. Human papillomavirus vaccination intention among young women in Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(12):3213–19. PMID:22471456.

- Siu JY. Barriers to receiving human papillomavirus vaccination among female students in a university in Hong Kong. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(9):1071–84. PMID:23826650. doi:10.1080/13691058.2013.807518.

- Kuo PF, Yeh YT, Sheu SJ, Wang TF. Factors associated with future commitment and past history of human papilloma virus vaccination among female college students in northern Taiwan. J Gynecol Oncol. 2014;25(3):188–97. PMID:25045431. doi:10.3802/jgo.2014.25.3.188.

- Juntasopeepun P, Suwan N, Phianmongkhol Y, Srisomboon J. Factors influencing acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccine among young female college students in Thailand. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;118(3):247–50. PMID:22727336. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.04.015.

- Huang H, Zhao FH, Xie Y, Wang SM, Pan XF, Lan H, Chen F, Yang CX, Qiao YL. Knowledge and attitude toward HPV and prophylactic HPV vaccine among college students in Chengdu. Xian Dai Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi(in Chinese). 2013;40:3071–80.

- Wang SM, Zhang SK, Pan XF, Ren ZF, Yang CX, ZZ W, XH G, Li M, Zheng QQ, Ma W, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine awareness, acceptability, and decision-making factors among Chinese college students. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(7):3239–45. PMID:24815477. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.7.3239.

- Zou H, Wang W, Ma Y, Wang Y, Zhao F, Wang S, Zhang S, Ma W. How university students view human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination: a cross-sectional study in Jinan.China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(1):39–46. PMID:26308701. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1072667.

- Wadhera P, Evans JL, Stein E, Gandhi M, Couture MC, Sansothy N, Sichan K, Maher L, Kaldor J, Page K, et al. Human papillomavirus knowledge, vaccine acceptance, and vaccine series completion among female entertainment and sex workers in Phnom Penh, Cambodia: the young women’s health study. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(12):893–902. PMID:25505042. doi:10.1177/0956462414563626.

- Wong LP, Sam IC. Ethnically diverse female university students’ knowledge and attitudes toward human papillomavirus (HPV), HPV vaccination and cervical cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;148(1):90–95. PMID:19910102. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.10.002.

- Kang HS, Moneyham L. Attitudes, intentions, and perceived barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among Korean high school girls and their mothers. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34(3):202–08. PMID:21116177. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181fa482b.

- Kang HS, Moneyham L. Attitudes toward and intention to receive the human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination and intention to use condoms among female Korean college students. Vaccine. 2010;28(3):811–16. PMID:19879993. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.052.

- Choi JS, Park S. A study on the predictors of Korean male students’ intention to receive human papillomavirus vaccination. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(21–22):3354–62. PMID:27378054. doi:10.1111/jocn.13461.

- Gupta V, Dawood FS, Muangchana C, Lan PT, Xeuatvongsa A, Sovann L, Olveda R, Cutter J, Oo KY, Ratih TS, et al. Influenza vaccination guidelines and vaccine sales in southeast Asia: 2008–2011. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52842. PMID:23285200. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052842.

- Wang H, Men P, Xiao Y, Gao P, Lv M, Yuan Q, Chen W, Bai S, Wu J. Hepatitis B infection in the general population of China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):811. . PMID:31533643. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4428-y.

- Wu XL, Zhou N, Sun C, Zhi QM, Wang YY, Li SQ. Prevalence and influencing factors of hepatitis B vaccination among college student in Yucheng city of Shandong province. Zhong Guo Gong Gong Wei Sheng Za Zhi(in Chinese). 2018;34:1282–84.

- Teng LX, Duan JL, Lv Y, Zhang JL, Xu N. Prevention and control of hepatitis B among college students in Beijing and vaccination situation. Zhong Guo Xue Xiao Wei Sheng Za Zhi(in Chinese). 2015;36:590–92.

- Wang L, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Zhang S. Understanding medical students’ practices and perceptions towards vaccination in China: a qualitative study in a medical university. Vaccine. 2019;37(25):3369–78. PMID:31076158. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.03.053.

- Bhattarai S, PM P, Rijal S, Rijal S, Rijal S. Hepatitis B vaccination status and needle-stick and sharps-related Injuries among medical school students in Nepal: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:774. PMID:25366873. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-774.

- Pathoumthong K, Khampanisong P, Quet F, Latthaphasavang V, Souvong V, Buisson Y. Vaccination status, knowledge and awareness towards hepatitis B among students of health professions in Vientiane, Lao PDR. Vaccine. 2014;32(39):4993–99. PMID:25066734. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.022.

- Siddiqui M, Khan AA, Varan AK, Esteves-Jaramillo A, Sultana S, Ali AS, Zaidi AKM, Omer SB. Intention to accept pertussis vaccine among pregnant women in Karachi, Pakistan. Vaccine. 2017;35(40):5352–59. PMID:28863869. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.033.

- Pandey D, Vanya V, Bhagat S, Vs B, Shetty J, Wu JT. Awareness and attitude towards human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine among medical students in a premier medical school in India. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40619. PMID:22859950. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040619.

- Al-Naggar RA, Al-Jashamy K, Chen R. Perceptions and opinions regarding human papilloma virus vaccination among young women in Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(6):1515–21. PMID:21338190.

- Lim ASE, Lim RBT. Facilitators and barriers of human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in young females 18–26 years old in Singapore: a qualitative study. Vaccine. 2019;37(41):6030–38. PMID:31473002. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.08.053.

- Wong LP. Knowledge and attitudes about HPV infection, HPV vaccination, and cervical cancer among rural southeast Asian women. Int J Behav Med. 2011;18(2):105–11. PMID:20524163. doi:10.1007/s12529-010-9104-y.

- Durusoy R, Yamazhan M, Tasbakan MI, Ergin I, Aysin M, Pullukcu H, Yamazhan T. HPV vaccine awareness and willingness of first-year students entering university in Western Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(6):1695–701. PMID:21338218.

- Wu S, Su J, Yang P, Zhang H, Li H, Chu Y, Hua W, Li C, Tang Y, Wang Q. Factors associated with the uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination in older and younger adults: a large, population-based survey in Beijing, China. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e017459. PMID:28951412. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017459.

- Wu S, Yang P, Li H, Ma C, Zhang Y, Wang Q. Influenza vaccination coverage rates among adults before and after the 2009 influenza pandemic and the reasons for non-vaccination in Beijing, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:636. PMID:23835253. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-636.

- Cheung K, Ho SMS, Lam W. Factors affecting the willingness of nursing students to receive annual seasonal influenza vaccination: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Vaccine. 2017;35(11):1482–87. PMID:28214045. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.02.001.

- Khan TM, Buksh MA, Rehman IU, Saleem A. Knowledge, attitudes, and perception towards human papillomavirus among university students in Pakistan. Papillomavirus Res. 2016;2:122–27. PMID:29074171. doi:10.1016/j.pvr.2016.06.001.

- Kang HS, De Gagne JC, Kim JH. Attitudes,intentions, and barriers toward influenza vaccination among pregnant korean women. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36(9):1026–38. PMID:25061824. doi:10.1080/07399332.2014.942903.

- Jung EJ, Noh JY, Choi WS, Seo YB, Lee J, Song JY, Kang SH, Yoon JG, Lee JS, Cheong HJ, et al. Perceptions of influenza vaccination during pregnancy in Korean women of childbearing age. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(8):1997–2002. PMID:27222241. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1119347.

- Yang HJ, Cho SI. Influenza vaccination coverage among adults in Korea: 2008–2009 to 2011–2012 seasons. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(12):12162–73. PMID: 25429683. doi:10.3390/ijerph111212162.

- Yi S, Nonaka D, Nomoto M, Kobayashi J, Mizoue T, Cowling BJ. Predictors of the uptake of a (H1N1) influenza vaccine: findings from a population-based longitudinal study in Tokyo. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18893. PMID:21556152. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018893.

- Liu C, Wang XF, Li Y, Liu WC. Studying on the influence of college students’ attitude towards Hepatitis B risk on their willingness to vaccine in Tianjin. Zhong Guo Wei Sheng Shi Ye Guan Li Za Zhi(in Chinese). 2019;36:231–34.

- Bruni L, Diaz M, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, Herrero R, Bray F, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Castellsagué X. Global estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage by region and income level: a pooled analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2016;4(7):e453–63. PMID:27340003. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30099-7.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influence vaccination coverage among pregnant women-United States, 2012–13 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(38):787–92. PMID:24067583.

- Freund R, Le Ray C, Charlier C, Avenell C, Truster V, Tréluyer JM, Skalli D, Ville Y, Goffinet F, Launay O, et al. Determinants of non-vaccination against pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza in pregnant women: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20900. PMID:21695074. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020900.

- Saitoh A, Saitoh A, Sato I, Shinozaki T, Nagata S. Current practices and needs regarding perinatal childhood immunization education for Japanese mothers. Vaccine. 2015;33(45):6128–33. PMID:26342849. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.069.

- Saitoh A, Saitoh A, Sato I, Shinozaki T, Kamiya H, Nagata S. Improved parental attitudes and beliefs through stepwise perinatal vaccination education. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(11):2639–45. PMID:28853971. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1368601.

- Woodring J, Pastore R, Brink A, Ishikawa N, Takashima Y, Tohme RA. Progress toward hepatitis B control and elimination of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus-Western Pacific Region, 2005–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(8):195–200. PMID:30817746. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6808a2.

- Kim JS, Choi JS. Factors influencing university nursing students’ measles vaccination rate during a community measles outbreak. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2017;10(1):56–61. PMID:27021836. doi:10.1016/j.anr.2015.11.002.

- Hu X, Xiao S, Chen B, Sa Z. Gaps in the 2010 measle SIA coverage among migrant children in Beijing: evidencefrom a a parental survey. Vaccine. 2012;30(39):5721–25. PMID: 22819988. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.007.

- Siani A. Measles outbreaks in Italy: a paradigm of the re-emergence of vaccine preventable diseases in developed countries. Prev Med. 2019;121:99–104. PMID:30763627. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.02.011.

- Palache A, Oriol-Mathieu V, Fino M, Xydia-Charmanta M. Seasonal influenza vaccine dose distribution in 195 countries (2004–2013): little progress in estimated global vaccination coverage. Vaccine. 2015;33:5598–605. PMID:26368399. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.082.

- Siedler A, Mankertz A, Feil F, Ahlemeyer G, Hornig A, Kirchner M, Beyrer K, Dreesman J, Scharkus S, Marcic A, et al. Closer to the goal: efforts in measles elimination in Germany 2010. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(Suppl1):S373–S380. PMID:21666187. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir068.

- Shono A, Kondo M. Factors that affect voluntary vaccination of children in Japan. Vaccine. 2015;33(11):1406–11. PMID:25529291. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.12.014.

- Wada K, Smith DR, Tang JW. Influenza vaccination uptake among the working age population of Japan: results from a national cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59272. PMID:23555010. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059272.

- Zhou M, Qu S, Zhao L, Campy KS, Wang S. Parental perceptions of human papillomavirus vaccination in central China: the moderating role of socioeconomic factors. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1688–96. PMID:30427755. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1547605.

- Sathian B, Babu MGR, van Teijlingen ER, Banerjee I, Roy B, Subramanya SH, Rajesh E, Devkota S. Ethnic variations in perception of human papillomavirus and its vaccination among young women in Nepal. Nepal J Epidemiol. 2017;7(1):647–58. PMID:28970947. doi:10.3126/nje.v7i1.17757.

- Mohd Azizi FS, Kew Y, Moy FM. Vaccine hesitancy among parents in a multi-ethnic country, Malaysia. Vaccine. 2017;35(22):2955–61. PMID:28434687. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.010.

- Mohd Sopian M, Shaaban J, Mohd Yusoff SS, Wan Mohamad WMZ. Knowledge, decision-making and acceptance of Human Papilloma Virus vaccination among parents of primary school students in Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19(6):1509-14. PMID:29936724. doi:10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.6.1509.

- Jain N, Euler GL, Shefer A, Lu P, Yankey D, Markowitz L. Human papillomavirus (HPV) awareness and vaccination initiation among women in the United States, national immunization survey-adult 2007. Prev Med. 2009;48(5):426–31. PMID:19100762. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.11.010.

- Jeudin P, Liveright E, Del Carmen MG, Perkins RB. Race, ethnicity, and income factors impacting human papillomavirus vaccination rates. Clin Ther. 2014;36(1):24–37. PMID:24417783. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.11.001.

- Zhou M, Zhao L, Kong N, Campy KS, Wang S, Qu S. Predicting behavioral intentions to children vaccination among Chinese parents: an extended TPB model. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(11):2748–54. PMID:30199307. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.

- Kessels SJ, Marshall HS, Watson M, Braunack-Mayer AJ, Reuzel R, Tooher RL. Factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake in teenage girls: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;30:3546–56. PMID:22480928. doi:10.1016/i.vaccine.2012.03.063.

- Kwong EW, Lam IO, Chan TM. What factors affect influenza vaccine uptake among community-dwelling older Chinese people in Hong Kong general outpatient clinics? J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(7):960–71. PMID:19207795. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02548.x.

- Heo JY, Song JY, Noh JY, Seo YB, Kim IS, Choi WS, Kim WJ, Cho GJ, Hwang TG, Cheong HJ. Low level of immunity against hepatitis A among Korean adolescents: vaccination rate and related factors. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(10):e97–e100. PMID:23769832. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2013.03.300.