ABSTRACT

Background

Measles outbreaks often require labor- and resource-intense response. A border-area measles outbreak occurred in Yunnan province that required outbreak response immunization for its containment. We report results of our investigation into the outbreak and the health sector costs of the response activities, with the goal of providing evidence for policy makers when considering the full value of vaccines and of measles elimination.

Methods

We conducted case investigations to determine sources of infection and routes of transmission. Costs of outbreak response activities incurred by health sector were determined through retrospective interviews and record reviews of staff.

Results

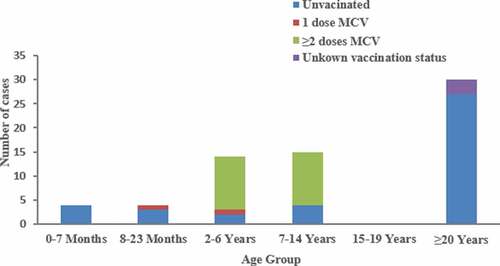

In total, 67 measles cases were confirmed, including 4 cases imported from Myanmar. Among the 33 cases aged between 8 months and 14 y old, 22 (66∙7%) had received 2 doses of MCV; 2 (6∙0%) had received 1 dose of MCV; 9 (27∙3%) had not received MCV. The first 4 cases had been infected in Myanmar, and we identified 8 transmission clusters with a total of 62 cases. Transmission among Yunnan province residents occurred in schools, family settings, and at gatherings. The overall cost to control the outbreak was $214,774, for a per-case cost of $3,206. The outbreak response vaccination campaign accounted for 64% of the total outbreak costs.

Conclusions

Despite high population immunity among Yunnan province children and adolescents, an import-related measles outbreak occurred among individuals who were not vaccinated or had vaccine failure in the across-border area. The economic cost of the outbreak was substantial. Investment in a sensitive measles surveillance system to detect outbreaks in a timely manner, maintaining high population immunity to measles, and reinforcing cross-border collaboration with neighboring countries support achieving and sustaining measles elimination in the border areas of China.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Measles is a highly infectious viral disease associated with fever and rash that occasionally causes serious complications, such as pneumonia and encephalitis, which can lead to death. China, as all countries in the World Health Organization Western Pacific Region, has a goal to eliminate measles. China has not yet eliminated measles, although significant progress has been made.Citation1 In the measles elimination era, outbreaks of measles must be contained, often with labor- and resource-intense response efforts. Quantifying the health and economic costs of measles outbreak response can provide evidence for policy makers on the full value of vaccines and the merits of measles elimination.

On 12 April 2017, an import-initiated measles outbreak in MD Town was confirmed by GengMa County Center for Disease and Prevention. Despite vigorous control efforts, the outbreak became the largest documented import-initiated measles outbreak in Yunnan in nearly a decade. We investigated the transmission patterns and the economic cost of outbreak response activities incurred by the health sector. We report the results of our investigation and estimates of resources required for the response.

Methods

Setting

The setting of this outbreak is Yunnan province, China. Yunnan is in southwest China and has an area of 394,000 km2, sharing 4,060 kilometers of international border with Myanmar in the west and southwest and with Vietnam and Laos in the south. Six of Yunnan’s 16 prefectures share a nearly 2000 kilometer border with Myanmar. There are few natural barriers between Myanmar and China, and border inhabitants interact frequently. Reports of infectious disease imports to Yunnan have been increasing since the 1990s. The last reported case of wild polio in Yunnan was a 1996 import from Myanmar; a vaccine-derived poliovirus case was imported in 2012; and a measles virus genotype previously unseen in China (D11) was detected in the Yunnan border area in 2009.Citation2–4

As one of the nine townships in GM County of Yunnan Province, MD Town is an underdeveloped area situated in the southwest of LC City, Yunnan. With its nearly 47∙35 kilometers of international borders, MD Town is adjacent to Kokang Special Administrative Region, an area that is out of effective management by the Myanmar central government. MD Town has 23 administrative villages in its 1,101 square kilometers. The population of MD Town was estimated to be 92,622 in 2016, with 16,080 children younger than 15 y of age and an annual birth rate of approximately 9∙49‰.

Yunnan vaccine policy history

Before the 1965 introduction of a liquid measles vaccine (MV), Yunnan had many outbreaks and an annual-reported measles incidence of more than 1,400 cases per million population. When the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) started in China in 1978, a 1-dose measles-containing vaccine (MCV) routine schedule was introduced, and starting in 1986, the program began using a 2-dose MCV immunization schedule with the first dose at 8 months and the second dose at 7 y. In 2008, the EPI schedule was changed to measles-rubella (MR) vaccine at 8 months and measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine at 18 months. Reported routine, 2-dose MCV coverage in Yunnan has been above 90% since 2004.

An accelerated measles elimination plan was initiated in 2006,Citation5 with key elements of the plan being achieving and maintaining 2-dose MCV coverage above 95% through routine immunization, conducting supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) among children to close immunity gaps, employing a sensitive and specific measles surveillance system, and responding rapidly to outbreaks. The incidence of measles in Yunnan decreased by more than 95% between 2006 and 2016, and during this time, the age distribution of measles cases changed – few measles cases have been reported among age-groups targeted by SIAs and routine immunization, while the percentage of cases among adults increased from 17% before plan implementation to 24% in 2016.

Case and outbreak definitions

We used World Health Organization measles case definitions: a suspected case of measles was defined as any person with fever (temperature, ≥37∙5°C), generalized maculopapular rash, and one or more of the following symptoms: cough, coryza, or conjunctivitis. Confirmed cases were those that had laboratory evidence of infection – positive serology for measles immunoglobulin M (IgM), and/or presence of measles RNA. In accordance with China’s National Measles Surveillance Guidelines, an outbreak is defined as the occurrence of two or more measles cases in a group setting (community, school, company, buildings) within 10 d. During an outbreak, any measles case with an epidemiological link with reported cases would be identified as an outbreak case. A measles outbreak can be declared over when no laboratory confirmed case occurs within 21 d from the onset of the last known case.

Outbreak investigation

Using a standardized form, county CDC staff conducted case investigations for each suspected measles case, obtaining demographic information, presence or absence of measles symptoms, measles vaccination history, travel during the 3 weeks prior to symptom onset, and number of contacts. Vaccination status of individuals less than 15 y old was determined using official, parent-held vaccination certificates. The vaccination status of those more than 15 y old is self-reported. Serum, urine, and throat specimens collected 0–7 d from rash onset and sent to Yunnan’s measles laboratory network for confirmation by serology and viral testing according to the approach recommended by WHO.Citation6

Control measures

After the measles outbreak was declared, the GM County Health Administrative Department established a measles emergency response team. Using measles outbreak standard operating procedures, outbreak response activities included patient treatment, outbreak investigation, active surveillance, an immunization campaign, coordination, and social mobilization.

To minimize transmission in health care settings, a single hospital was designated to provide treatment, care, and isolation for measles patients.

We conducted an active search for additional suspected measles cases to facilitate determining sources of infection and transmission chains; contact tracing and identified suspected cases were reported through the measles surveillance system. We reviewed medical records from all GM County township- and county-level hospitals, and local staff conducted house-to-house active search for measles cases in the affected townships and neighboring areas. Two rounds of outbreak response immunization (ORI) were conducted. The ORI activities were conducted in community health center and village clinics. The emergence response team prepared the list of the eligible persons and urging the eligible persons, who missed the emergency immunization, to receive the vaccine.

Cost data acquisition and analysis

We conducted retrospective surveys in September 2017. We examined health care institutions involved in the response to evaluate activities performed, time spent by personnel, materials, and direct costs related to containing the measles virus for a period extending from the recognition of index case until control efforts ceased (i.e., from April 9 to July 5, 2017). We conducted semi-structured interviews with leaders of each institution to describe post-outbreak control activities. Costs were assessed in one designated hospital, 4 community healthcare centers, 23 village clinics, and county-, city-, and province-level CDCs. These involved institutions completed surveys, with a response rate of 100%. In total, 15 clinical doctors, 40 public health doctors, 32 nurses, and 55 rural doctors participated in the outbreak response activities. Health sector costs for outbreak response included the following components: outbreak investigation, laboratory testing, health-facility-based treatment of persons with measles, active surveillance for measles cases, outbreak response immunization, coordination, and social mobilization.

Personnel time was converted to costs by using average 2017 salaries in Yunnan (234 workdays, 8 hours per workday).Citation7 Labor costs were determined by multiplying personnel hours or workdays by the hourly or daily earnings in the health care industry. Costs included expenses for materials for outbreak response immunization, laboratory test kits, educational posters, and miles traveled at 0 USD∙1 per mile. Overhead costs, fringe benefits, and costs of phone calls were not included. All costs were measured in 2017 RMB and converted to 2017 US dollars based on the average currency conversion rates of 6∙7 RMB per 1 US dollar.

Ethical considerations

Measles outbreak investigations are considered by Yunnan CDC’s Ethical Review Committee to be exempt from IRB review as they are considered public health program work and evaluation. Individual identifying data were not retained in analytic data sets.

Results

Outbreak profile

The index case was a 22-y-old Chinese man with unknown vaccination status, who had been exposed to his wife when she had a measles-like illness in Myanmar in mid-March 2017. On 26 March 2017, the index patient returned from Myanmar to MD Town for tomb sweeping during Qingming Festival. He transmitted measles virus to other family members and friends during the Qingming Festival gathering.

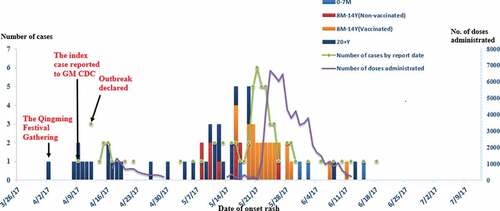

A total of 67 measles cases was confirmed out of 92 suspected cases; four were imported from Myanmar. Active search identified 28 suspected cases (30∙4%). Rash onsets occurred from 2 April through 15 June 2017 (). The measles incidence was 68∙0/100,000 in this outbreak – higher than any corresponding period from 2007 through 2016 when the incidence ranged from 0 to 4∙3 per100,000.

Figure 1. Distribution of measles cases by rash onset date and reporting date, and number doses of measles vaccine administered in the outbreak response

Among confirmed cases, 34 (50∙7%) were male. By residency status, indigenous cases lived in 15 (65∙2%) of 23 administrative villages in MD Town. The median age of the cases was 9 y (range: 3 months to 49 y); four (6∙0%) were less than 8 months old; 33 (49∙3%) were between 8 months and 14 y old; 30 (44∙7%) were more than 20 y old. Among 33 cases aged between 8 months and 14 y old, 22 (66∙7%) had received 2 MCV doses; two (6∙0%) had received 1 MCV dose; nine (27∙3%) had not been vaccinated against measles. Among the nine unvaccinated cases, six had not been vaccinated because they were children who migrated from Myanmar with their parents; the remaining three had not been vaccinated because of false contraindications to MCV. Among the 30 adults, 27 were documented to have not been vaccinated against measles; the remaining three cases had unknown vaccination status ().

Transmission patterns

We identified eight transmission clusters with a total of 62 cases (). The index cases initiated one generation of measles transmission, infecting 11 others. The other three imported cases led three, two, and one generations of transmission with 12, 16, and 9 cases, respectively. Transmission among the Yunnan resident cases occurred in schools (n = 15), during Qingming Festival gatherings (n = 10) and wedding parties (n = 6), within families (n = 12), in communities (n = 8), and in health care settings (n = 3). There were nine additional cases with unknown routes of measles virus acquisition.

Control measures and costs

Two rounds of outbreak response immunization (ORI) were conducted. Initially, ORI was nonselective (without regard to vaccination history), targeting 20–40 y-old adults living near a measles case (in five administrative villages). There were no measles cases reported in these villages after the ORI. From 22 May through 12 June, as Myanmar importations continued, larger ORI activities targeting children and adults were conducted in the remaining 18 administrative areas of MD Town and the neighboring 3 townships. In total, 23,755 (92∙4%) of 25,712 targeted 8 m–14-y-old children and adolescents were vaccinated, and 50,018 (81∙5%) of 61,372 targeted 20–49 y-old adults were vaccinated ().

The overall cost to control the outbreak was 214,774, USD for a per-case cost of 3,206. USD Costs were covered by government. Labor, material, and transportation costs accounted for 64.3%, 32.5%, and 1.3%, of total costs. Approximately 20,249 hours of personnel time were spent controlling the outbreak, of which 52.9%, 20.7%, and 13∙5% were for ORI, active surveillance, and illness treatment and care, respectively. Approximately half of personnel time was incurred by community health centers and village clinics ().

Table 1. Estimated response costs

Discussion

This 67-case measles outbreak was the largest documented importation outbreak in Yunnan Province in nearly a decade. The outbreak created substantial health risk and required a vigorous and expensive public health response. The source cases were from Myanmar, but transmission occurred among Yunnan residents. The outbreak started in adults and spread initially to unvaccinated children and subsequently to age-appropriately vaccinated children and to infants too young to vaccinate with measles vaccine. Transmission occurred in gatherings of families and friends and in health care facilities during the early stages of the outbreak, and to schools and community settings in latter stages. Outbreak response immunization that targeted adults and children appeared to be necessary to stop the outbreak, and may have been effective to decrease the magnitude and duration of the outbreak.

Our investigation showed that failure to vaccinate and vaccine failure both facilitated measles transmission in Yunnan. Nine children had missed opportunities to immunize, including six Myanmar children living in Yunnan. Egg allergy has been a (false) contraindication to MCV in some immunization clinics in MD town. Measles outbreaks have been associated with false contraindications to vaccination MCVCitation8 previously in China. We believe that high rates of coverage with two doses of MCV for children is essential and that high coverage should be homogeneous, avoiding pockets of susceptible children.

Twenty-two individuals (66∙7% of the vaccination-age cases) who had received 2 MCV doses developed measles, which could be due to 2-dose primary vaccine failure or secondary vaccine failure. Possible reasons include failure to maintain the cold chain or greater intensity of exposure during this outbreak. Adults 20–49 y of age comprised 44∙7% of outbreak cases.

Study in the context of the scientific literature

Adult outbreaks have been reported more frequently in China in recent years.Citation9,Citation10 As Orenstein and colleagues suggested, it is difficult to believe that adult patients can sustain a chain of transmission in the general population.Citation11 Several authors suggest that if there are high coverage rates among schoolchildren, it is difficult for an outbreak to propagate in a community, even in the presence of susceptible adults.Citation12,Citation13 However, in a recent study in China, and in this outbreak, it appeared that measles virus had transmitted among adults – a situation that may pose a threat to measles elimination.Citation14 A recent serological survey in Yunnan shown that the measles seropositive level among adults aged 20–39 was the lowest of all age groups in the province.Citation15

The cost of managing measles outbreaks has been an object of study in developed countries.Citation16–19 Ma and colleagues reported economic costs associated with a measles outbreak in Beijing, China.Citation20 Compared to Yunnan Province, however, the average income per capita is much higher in Beijing and in developed countries. Similar studies in low and middle-income area are necessary to better understand outbreak costs. In previous reports, the per-case cost of managing an outbreak varied from 115 USD to 83,580 USD,Citation16–22 with variation due to differences in outbreak setting, control measures, and labor and material costs. In our study, the health care sector control cost was 3,206 USD per case, which is less than the 17,481 USD response cost per case in Beijing but much greater than the 33 USD∙11 per-case cost in Ethiopia.Citation23 The outbreak response vaccination campaign accounted for 64% of the costs – 2,052 USD∙8 per case – which was much higher than the cost of 92.42 USD to fully vaccinate each child through routine immunization in China.Citation24 Such a comparison highlights that enhancing measles surveillance and improving routine immunization quality and coverage in underdeveloped border areas could avoid some expensive outbreak response costs.

Cross-border population movement impedes efforts to prevent transmission of infectious diseases, which in turn poses great challenge for measles elimination. Importation of measles or any vaccine preventable disease poses a risk of exposure to unvaccinated individuals and often requires a public health response to prevent or reduce domestic transmission. As we have shown in this outbreak, responses can be costly because they are labor intensive – a finding that is consistent with the intensity of the 2018–2019 measles outbreak response in New York City.Citation25

Limitations

There are limitations we were unable to address in our investigation: (1) The avidity of IgG test was not available in our measles laboratories, therefore, the type of vaccine failure for each measles case could not be definitively identified; (2) due to lack of data, many costs were excluded, the total cost for measles cases and their households were not included in our analysis. (3) Costs were measured retrospectively, potentially leading to recall bias. We tried to overcome recall bias by use of memory aids in our interviews. Because our costs did not include overhead costs, fringe benefits, or costs for phone calls, the response costs may have been underestimates. (4) Due to the lack of the related record, some patients and their families/caregivers in hospital clinics and passengers in public transportation systems, who might have contacts with our measles cases or were exposed in a closed area occupied by measles cases for the subsequent several hours, were not targeted by our control activities. Therefore, the true outbreak size and the number of contacts might be underestimated. However, it should be noted that given the underestimation, the real controlling costs would be higher.

Program implications

We believe that our study supports three recommendations. First, public health officials should stay alert for imported measles cases and adult-to-adult transmission of measles in outbreaks and should consider early vaccination of adults in outbreaks. Second, government should consider increasing financing to strengthen immunization services in border regions, identify good practices for conducting outreach to children of immigrants, and ensure that immunization clinics do not restrict access to services for cross-border children. Third, the province should build a collaborating mechanism for measles elimination with Myanmar and other neighboring countries, possibly including sharing measles surveillance and coverage data and conducting regular cross-border meetings to better understand each other’s public health systems, and, in the case of a border outbreak, to synchronize outbreak response immunization.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank staff in Lincang city CDC, Gengma county CDC for their efforts made in the field investigation. We thank Dr. Lance Rodewald for his suggestions and English polishing of our manuscript.

References

- Ma C, Rodewald L, Hao LX, Su Q, Zhang Y, Wen N, Fan C, Yang H, Luo H, Wang H, et al. Progress toward measles elimination — China, January 2013–June 2019. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep MMWR. 2019;68:112–16. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6848a2.

- Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication–Myanmar, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1996-1999. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep MMWR. 1999;48(42):967–71.

- Wang H-B, Zhang L-F, Yu W-Z, Wen N, Yan D-M, Tang -J-J, Zhang Y, Fan C-X, Reilly KH, Xu W-B, et al. Cross-border collaboration between China and Myanmar for emergency response to imported vaccine derived poliovirus case[J]. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):18. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-0745-y.

- Zhang Y, Ding Z, Wang H, Li L, Pang Y, Brown KE, Xu S, Zhu Z, Rota PA, Featherstone D, et al. New measles virus genotype associated with outbreak, China[J]. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(6):943. doi:10.3201/eid1606.100089.

- MOH. National plan of measles elimination in China 2006–2012; Accessed 15 December 2019. http://www.moh.gov.cn/jkj/s3581/200804/361e2acfadcc4e93bcac60235d307a48.shtml.

- World Health, Organization. Measles virus nomenclature update: 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2012;87:73–81.

- National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. Yunnan statistical yearbook. Beijing: China statistical Press; 2017.

- Su Q, Zhang Y, Ma Y, Zheng X, Han T, Li F, Hao L, Ma C, Wang H, Li L, et al. Measles imported to the United States by children adopted from China.[J]. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):1032–37. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1947.

- Wang F-J, Sun X-J, Wang F-L, Jiang L-F, Xu E-P, Guo J-F. An outbreak of adult measles by nosocomial transmission in a high vaccination coverage community.[J]. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;26(C):67–70. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2014.05.006.

- Zhao Z, Zhou R, Yu W, Li L, Li Q, Hu P. Measles outbreak prevention and control among adults: lessons from an importation outbreak in Yunnan Province, China, 2015[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(1). doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1417712.

- Orenstein WA, Strebel PM, Papania M, Sutter RW, Bellini WJ, Cochi SL. Measles eradication: is it in our future?[J]. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(10):1521–25.

- Parker A, Staggs W, Dayan GH, Ortega-Sánchez IR, Rota PA, Lowe L, Boardman P, Teclaw R, Graves C, LeBaron CW. Implications of a 2005 measles outbreak in Indiana for sustained elimination of measles in the United States[J]. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(5):447–55. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060775.

- Ehresmann KR, Crouch N, Henry PM, Hunt JM, Habedank TL, Bowman R, Moore KA. An outbreak of measles among unvaccinated young adults and measles seroprevalence study: implications for measles outbreak control in adult populations.[J]. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(Suppl 1):S104–7. doi:10.1086/377714.

- Ma C, Yan S, Su Q, Hao L, Tang S, An Z, He Y, Fan G, Rodewald L, Wang H. Measles transmission among adults with spread to children during an outbreak: implications for measles elimination in China, 2014.[J]. Vaccine. 2016;34(51):6539–44. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.02.051.

- Zhao ZX, Zhou RR, Li LQ, Yu W, Li QF, Hu P. Analysis of measles immunity level and serological susceptibility among Yunnan residents aged ≥20years. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2018;52:50–54. in Chinese. doi:10.3760/cma.j..0253-9624.2018.01.010.

- Dayan GH, Ortega-Sánchez IR, Lebaron CW. The cost of containing one case of measles: the economic impact on the public health infrastructure–Iowa, 2004.[J]. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):1–4. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-2512.

- Coleman MS, Garbat-Welch L, Burke H, Weinberg M, Humbaugh K, Tindall A, Cambron J. Direct costs of a single case of refugee-imported measles in Kentucky.[J]. Vaccine. 2012;30(2):317–21. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.091.

- Ghebrehewet S, Thorrington D, Farmer S, Kearney J, Blissett D, McLeod H, Keenan A. The economic cost of measles: healthcare, public health and societal costs of the 2012-13 outbreak in Merseyside, UK.[J]. Vaccine. 2016;34(15):1823–31. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.02.029.

- Coleman MS, Burke HM, Welstead BL, Mitchell T, Taylor EM, Shapovalov D, Maskery BA, Joo H, Weinberg M. Cost analysis of measles in refugees arriving at Los Angeles International Airport from Malaysia[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(5):1084–90. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016.1271518.

- Ma R, Lu L, Suo L, Li X, Yang F, Zhou T, Zhai L, Bai H, Pang X. An expensive adult measles outbreak and response in office buildings during the era of accelerated measles elimination, Beijing, China.[J]. Vaccine. 2017;35(8):8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.01.021.

- Ortega-Sanchez IR, Vijayaraghavan M, Barskey AE, Wallace GS. The economic burden of sixteen measles outbreaks on United States public health departments in 2011[J]. Vaccine. 2014;32(11):1311–17. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.012.

- Wendorf KA, Kay M, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Munn M, Duchin J. Cost of measles containment in an ambulatory pediatric clinic[J]. Pediatric Infect Dis J. 2015;34(6):589–93. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000000682.

- Wallace AS, Masresha BG, Grant G, Goodson JL, Birhane H, Abraham M, Endailalu TB, Letamo Y, Petu A, Vijayaraghavan M. Evaluation of economic costs of a measles outbreak and outbreak response activities in Keffa Zone, Ethiopia[J]. Vaccine. 2014;32(35):4505–14. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.035.

- Yu W, Lu M, Wang H, Rodewald L, Ji S, Ma C, Li Y, Zheng J, Song Y, Wang M, et al. Routine immunization services costs and financing in China, 2015.[J]. Vaccine. 2018;36(21):3041–47. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.008.

- Zucker JR, Rosen JB, Imawoto M, Arciuolo RJ, Langdon-Embry M, Vora NM, Rakeman JL, Isaac BM, Jean A, Asfaw M, et al. Consequences of undervaccination - measles outbreak, New York City, 2018–2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1009–17. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1912514.