ABSTRACT

Background

Though human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination is a safe and effective method of protecting against associated cancers, uptake rates remain low among adolescents. Few studies have examined how social media use contributes to HPV-related knowledge gaps among parents and caregivers.

Objective

To investigate the association between social media use and HPV-related awareness and knowledge with a focus on differences by gender and race/ethnicity among a nationally representative sample of adults with children in the household.

Methods

We used data from the Health Information National Trends (HINTS) Survey (2017–2019) (N = 2,720). Multivariate logistic regressions were used to examine the association of social media use on HPV awareness and knowledge outcomes.

Results

Compared to non-users, engaging in one, two, three, or four social media behaviors were associated with greater HPV awareness (aOR: 2.09; 95%CI: 1.18–3.70, aOR: 2.49; 95%CI: 1.40–4.42, aOR: 2.64; 95%CI: 1.15–6.05, and aOR: 2.44; 95%CI: 1.11–5.36, respectively). Increased social media use was associated with increased HPV vaccine awareness. Men, African American, Hispanic, and Asian American respondents were less likely to be aware of HPV or HPV vaccine. Social media use was not associated with cancer knowledge.

Conclusions

Increased social media use is associated with an increased awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine for adults with children in the household. Social media-based efforts can be utilized to increase knowledge of the benefits of HPV vaccination as cancer prevention, which may be a precursor to reducing HPV vaccine hesitancy and encouraging uptake to decrease cancer incidence rates among vulnerable populations.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infections (STI) and can lead to several types of cancer among men and women. Adverse outcomes can be prevented by vaccination, which has been recommended for children beginning 9 to 11 years old in the United States. The nonavalent vaccine protects against strains of HPV 16 and 18, which are associated with cancers of the cervix, penis, anus, mouth, oropharynx, larynx, vulva, and vagina, as well as HPV 6 and 11, which cause 90% of genital warts cases.Citation1 However, uptake remains low in the US, with only 49.5% for females and 37.5% for males aged 13–17 completing the recommended series.Citation2

Social media, defined as “a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation and exchange of user generated content” (p 61),Citation3 can be utilized for surveillance and communication of health-promoting behaviors. Social media use is common among American parents, as the majority use Facebook (74%). Mothers are more likely to use Facebook (81%), Pinterest (40%), and Instagram (30%), compared to fathers (66%, 15%, and 19%, respectively).Citation4 According to Pew data, in the US, parents interact with their social networks as opposed to only reading or viewing content, with 37% of mothers frequently sharing, posting, or commenting on Facebook. Social media also serves as a source for parenting advice and information, with 59% of parents finding parenting information on social media content, 42% receiving social support on parenting issues, and 31% asking parenting questions.Citation4

Social media use and health information seeking online is increasing, with 69% of American adults use at least one social media site, 72% of US adults looked for health information online, and over one-third used the Internet to try to diagnose a medical condition.Citation5 Indeed, it is critical to address research gaps on how social media may inform HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge, which may inform decisions on vaccine uptake. Multiple studies have examined HPV sentiment and content on various social media platforms such as YouTube,Citation6,Citation7 microblogs,Citation8 Pinterest,Citation9 Twitter,Citation10,Citation11 and Instagram.Citation12,Citation13 On YouTube, the most viewed videos related to HPV and HPV vaccine were anti-vaccine (57%) compared to pro-vaccine (31%) and neutral (11%) in nature.Citation8 In contrast, Briones et al. (2012) found that 33% of videos were pro-vaccine, potentially indicating the increase in anti-vaccine content on YouTube.Citation6 Similarly, Keim-Malpass et al. (2017) found that on Twitter, 51% of the tweets were classified as “positive” and 44% of the Tweets were considered “negative”Citation14

Similarly, on Pinterest, vaccine side-effects and safety were primary concerns of users. An overwhelming majority of “pinned” images were anti-vaccine (74%) compared to pro-vaccine content (18%).Citation9 Proliferation of anti-vaccine content and “false” (i.e. misinformation) vaccine information through malicious actors on social media may amplify negative sentiment and drive hesitancy.Citation15 Margolis et al. (2018) found that parents of adolescents who heard negative stories of HPV (e.g. side effects) were less likely to initiative HPV vaccination compared to parents who heard positive or no stories.Citation16 As the use of social media continues to spread, the need to examine the role of social media on HPV-related knowledge becomes increasingly clear.

Exposure to health information on social media may shape knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs, which, in turn, may shape parents’ intentions to get their children vaccinated against HPV. Prior studies have examined how online health-seeking behaviors contribute to HPV-knowledge disparitiesCitation17 and the role of social media on impacting individuals’ awareness of HPV.Citation18 However, focus has been largely on adolescents and young adults, highlighting a need to investigate social media use among parents and caregivers related to HPV. Additionally, research indicates that HPV awareness and knowledge are lower among racial/ethnic minorities and men, which is troubling as HPV can result in several types of cancers among men and women, with ethnic/racial minorities bearing disproportionate burden of disease.Citation19

Minority women are more likely to be at risk for cervical cancer compared to white women,Citation19,Citation20 with the highest incidence rate of cervical cancer among Latina women (9.7 per 100,000 women), followed by African-American women (9.2 per 100,000 women). African-American and Latina women also have higher rates of vaginal and vulvar cancers compared to white women. Men who are minorities disproportionately experience HPV-related cancer disparities. Black men had the highest rates of HPV-associated anal cancer (1.5 men per 100,000), compared to white (1.1 men per 100,000) and Hispanic (0.7 men per 100,000) men.Citation19 Hispanic men have higher rates of penile cancer than non-Hispanic men.Citation21 For oropharyngeal (head and neck) cancers, black men had the second highest rates (6.8 men per 100,000). Given that HPV-attributable oropharyngeal cancers currently exceed cervical cancer ratesCitation21 and that these cancers are often detected at advanced stages,Citation22 increasing male HPV vaccination rates is a public health imperative. Additionally, vaccinating males confers additional protection among men who have sex with men (MSM) who do not benefit from female-only vaccination.

Racial, ethnic, and gender disparities are observed with HPV vaccine initiation and completion. National Immunization Surveys (NIS)-Teen data reported that Latino and African American adolescents are more likely to begin initiation of HPV vaccination, but are less likely to complete the vaccine series, compared to Whites.Citation23,Citation24 An examination from the 2013 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) found that African Americans and males were less likely to initiate HPV vaccination.Citation25 Similarly, Daniel-Ulloa et al. (2016) found that women were more likely to report receiving the HPV vaccine (30%) compared to men (5%), consistent with recent research.Citation26,Citation27 Further, African American women had lower odds of HPV vaccine series initiation. Among women who initiated HPV vaccination, African American and Latina women had approximately were less likely to complete the series compared to White women,Citation26 potentially due to gaps in continuity of care, insurance coverage, access to healthcare as well as lower quality of care.Citation28 Concerted, culturally relevant efforts need to be placed on promoting vaccines among women and men, particularly racial/ethnic minorities to prevent worsening HPV-related disease rates and promote health and well-being.

Investigating the role of social media use on HPV awareness and knowledge and any differences by race/ethnicity and gender may help guide efforts to promote HPV vaccination and reduce cancer incidence rates among vulnerable populations. This study seeks to address these gaps by investigating the association between social media use and HPV-related awareness and knowledge outcomes among a nationally representative sample of adults with children in the household. Further, racial/ethnic and gender disparities in HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge will be assessed.

Methods

Population and study sample

Data were obtained from Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) 5, cycles1-3, administered by the National Cancer Institute. HINTS is a nationally-representative, publicly available, probability survey of adults aged 18 or older in the civilian non-institutionalized population of the United States. The sampling strategy was a two-stage design. In the first stage, a stratified sample of addresses was selected from a file of residential addresses and in the second stage, one adult was selected within each sampled household. Cycle 3 data were collected from January through May, 2019 (response rate = 30.3%; N = 5,438). Cycle 2 data were collected from January through May, 2018 (response rate = 32.8%; N = 3,504); Cycle 1 data were collected January through May, 2017 (response rate = 32.4%; N = 3,191). All three cycles were paper-mail surveys, however Cycle 3 introduced a Web Pilot wherein respondents were offered a choice between responding via paper or web. HINTS contained both final sample weights that helped obtain population-level estimates and a set of 50 replicate sampling weights to obtain the correct standard errors. Sampling weights ensure valid inferences from the responding sample to the population, correcting for nonresponse and noncoverage biases. Full descriptions of HINTS survey methodology have been published elsewhere.Citation29

Analyses focused on a subset of survey data comprising of men and women with at least one child in the household <18 years old across HINTS 5.1, 5.2, and 5.3 (N = 2,720). Racial/ethnic groups were restricted to non-Hispanic African American, Hispanic, Asian American, and non-Hispanic White adults.

Outcomes

HPV and HPV vaccine awareness

HPV awareness was drawn from the following item asking: “Have you ever heard of HPV? HPV stands for Human Papillomavirus. It is not HIV, HSV, or herpes.” HPV vaccine awareness was drawn from this item: “A vaccine to prevent HPV infection is available and is called the cervical cancer vaccine or HPV shot. Before today, have you ever heard of the cervical cancer vaccine or HPV shot?”. Both item responses were coded as a categorical variable (yes/no).

HPV cancer knowledge

HPV cancer knowledge were assessed with the following items: (1) “Do you think HPV can cause cervical cancer?”; (2) “Do you think HPV can cause penile cancer?”; (3) “Do you think HPV can cause anal cancer?”; (4) “Do you think HPV can cause oral cancer?”. Responses to survey items were dichotomized to be “yes” versus “no,” which consisted of “no” and “not sure” to reflect uncertainty or lack of cancer knowledge.

Predictors

Social media use

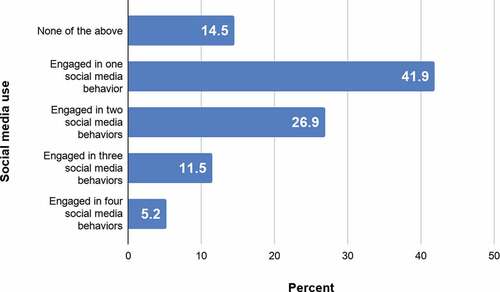

A composite social media use variable was created as the sum of responses to the following questions regarding behaviors in the past 12 months: (1) social networking site (SNS) use; (2) social networking site (SNS) use to share health information; (3) participation in online forum or support groups for health issue; and (4) watching health-related videos on YouTube. Responses to survey item were dichotomized to “yes” (1) or “no” (0). Yes responses were summed to create the composite social media variable. Cronbach alpha for the four social media items was 0.91, demonstrating robust internal consistency.

Covariates

Sociodemographic, cultural, and healthcare variables

The following covariates were included: age (18–34, 35–49, 50–65, >65 years old), gender (male, female), marital status (married/living as married, divorced/separated/widowed and single, never married), education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate, or more), household income ($0 to 19,999, USD 20,000 USD to 34,999, USD 35,000 USD to 49,999, USD 50,000 USD to 74,999, USD 75,000 to 99,999, USD 100,000 USD or more), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic African American, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, Asian American), English language proficiency (very well/well, not very well/not at all), regular provider status (yes/no), and general health status (excellent/very good, good, fair/poor). Measures were selected and categorized based on previous studies.Citation30,Citation31

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata 15.1. Descriptive statistics were reported for outcome and sociodemographic predictor variables. Bivariate relationships between the predictors (social media use) and outcomes (HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge) were examined using chi-square tests at the at p <.05 significance level. Multivariate logistic regressions were used to examine the association between social media use and HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and cancer knowledge. Following HINTS analytic recommendations, survey-specific procedures were used to account for the complex sampling design. Replicate weights were used to compute accurate standard errors for statistical testing procedures and to represent the U.S. population. Missing data were excluded from analysis.

Results

Sample

summarizes the sociodemographic, cultural, healthcare, and behavioral characteristics as well as HPV and social media related outcomes of respondents who reported living with children under 18 years old in the household (N = 2,720). Participants had a mean age of 43.6 years (SE = 0.3) and were mostly between the ages of 35–49 (50.5%) and female (56.2%). The racial demographics of the respondents were non-Hispanic White (54.6%), non-Hispanic Black (11.1%), Hispanic (24.0%), and Asian (6.4%). Of the respondents, 72.9% had heard of HPV and 70.5% had heard of the HPV vaccine. Related to HPV cancer knowledge, respondents were most familiar with HPV linkage to cervical cancer (78.2%), followed by penile cancer (33.4%), oral cancer (30.6%) and anal cancer (29.5%). Nearly 41% of respondents had used one form of social media, 5.5% had engaged in all four behaviors, while 14.1% had not used any social media in the past 12 months (). In contrast, the overall population of adults, including adults with and without children in the household, skewed older with a mean age of 53.6 years (SE = 0.2) and were mostly between the ages of 50–65. Consisting of 51.3% women, the overall population consisted of 10.8% non-Hispanic African American, 15.5% Hispanic, 5.2% Asian American, and 65.7 non-Hispanic White. This population had lower awareness of HPV and HPV vaccination (62.1% and 63.0%, respectively) compared to the analytic sample. Knowledge of cervical cancer was similar to the analytic sample at 78.2%, however lower for penile (30.0%), oral (29.3%), and anal (26.5%) cancers. Twenty-six percent of the overall population had not used any social media in the past 12 months, whereas 39.5% had engaged in at least one behavior, and 2.9% had engaged in all four behaviors.

Table 1. Respondent characteristics with children <18 in the household, 2019–2017 (N = 2,720)

HPV awareness

Bivariate analyses using chi-square tests revealed that increased social media use was associated with higher HPV awareness (p < .001). Compared to non-users (47.5%), those that engaged in three (81.9%) or all four (80.9%) behaviors had the greatest HPV awareness. In the first multivariable logistic regression model, increased social media use was associated with increased odds of being aware of HPV (). Compared to non-users, engaging in one, two, three, or four social media behaviors were associated with a greater likelihood HPV awareness (aOR: 2.09; 95%CI: 1.18–3.70, aOR: 2.49; 95%CI: 1.40–4.42, aOR: 2.64; 95%CI: 1.15–6.05, and aOR: 2.44; 95%CI: 1.11–5.36, respectively).

Table 2. Weighted frequencies and bivariate associations between HPV awareness and HPV vaccine awareness and social media use variables

Table 3. Weighted frequencies and bivariate associations between HPV cancer knowledge and social media use variables

Table 4. Weighted, fully adjusted multivariable logistic regression of the association between social media use and HPV and HPV vaccine awareness, 2019–2017

Men had significantly decreased odds of being aware of HPV compared to women (aOR: 0.38; 95%CI: 0.25–0.58). Those with lower educational attainment had decreased odds of HPV awareness, particularly for those with less than high school education (p < .001) and high school graduates (p < .001), compared to college graduates. Compared with non-Hispanic whites, African Americans (aOR: 0.53; 95%CI: 0.31–0.92) and Asians had significantly lower odds of being aware of HPV (aOR: 0.17; 95%CI: 0.09–0.32).

HPV vaccine awareness

Bivariate analyses demonstrated that increased social media use was associated with higher HPV vaccine awareness (p < .001), with adults that engaged in three (84.9%) or all four (82.9%) behaviors having the greatest awareness (). Multivariate analyses demonstrated that increased social media use was associated with increased odds of HPV vaccine awareness (). Compared to adults that did not use any social media, engaging in one, two, three, or four social media behaviors was associated with a greater HPV vaccine awareness (aOR: 2.21; 95%CI: 1.29–3.79, aOR: 2.89; 95%CI: 1.70–4.91, aOR: 5.16; 95%CI: 2.51–10.60, and aOR: 3.61; 95%CI: 1.53– 8.53, respectively).

Similar to HPV awareness, men had significantly decreased odds of being aware of HPV vaccination compared to women (aOR: 0.38; 95%CI: 0.25–0.58). Those with lower educational attainment had decreased odds of HPV vaccine awareness, particularly for those with less than high school education (p < .001) and high school graduates (p < .001), and some college (p < .001), compared to college graduates. Compared with non-Hispanic whites, African Americans (aOR: 0.48; 95%CI: 0.29–0.81), Hispanic (aOR: 0.62; 95%CI: 0.41–0.93), and Asians had significantly lower odds of being aware of HPV vaccination (aOR: 0.16; 95%CI: 0.09–0.28).

HPV cancer knowledge

Social media use was not associated with knowledge that HPV causes cervical, penile, oral, and oral cancers (). Multivariate analyses demonstrated that social media use was not associated with HPV-associated cancer knowledge (). Men had significantly lower odds of knowing that HPV causes cervical cancer (aOR: 0.58; 95%CI: 0.38–0.88) compared to women. Those who were high school graduates (p < .01) or had less than high school (p < .01) education were less likely to be knowledgeable that HPV causes cervical cancer. Marital status was associated with HPV-associated cancer knowledge. In particular, adults that were divorced, separated, or widowed had increased odds of penile and oral cancer knowledge (p < .05). Differences across race/ethnicity were not found across cancer knowledge.

Table 5. Weighted, fully adjusted multivariable logistic regression of the association between social media use and HPV cancer knowledge, 2019–2017

Multivariate analyses stratified by gender and race/ethnicity

Given the significance of gender in our models, we conducted additional logistic regression models examining the association between social media use on HPV awareness and knowledge outcomes stratified by gender (Appendix). Among women, those that engaged in any social media had significantly increased odds of having heard of HPV compared to non-users, with those that engaged in three social behavior having the greatest odds (aOR: 6.84; 95%CI: 2.09–22.29). Similarly, for HPV vaccine awareness, women that engaged in any social media had significantly increased odds of having heard of HPV vaccination compared to non-users, with those that engaged in three social behavior having the greatest odds (aOR: 8.78; 95%CI: 2.98–25.89). Among men, the models did not yield major significant results for HPV and HPV vaccine awareness or cervical cancer knowledge. Race/ethnicity-stratified results did not demonstrate major significant results across HPV or HPV vaccine awareness.

Discussion

Using nationally representative data, this study examined the association between the level of social media use and HPV knowledge and awareness among adults with children under 18 years old in the household. We found that a majority of respondents were aware of HPV, HPV vaccine, and knowledgeable of HPV’s linkage with cervical cancer, but less so about penile, anal, and oral cancer, in line with recent studies.Citation31,Citation32 Study findings indicated that social media users had significantly higher odds of being aware of HPV and HPV vaccination, compared to non-users. Increased social media use may facilitate increased direct or passive consumption of information online, corresponding with increased awareness. Social media use was not associated with knowledge that HPV causes certain cancers, warranting efforts to increase HPV cancer knowledge.

Results highlight important HPV-related awareness gaps between those that use social media and those who do not. Racial/ethnic minorities and men had significantly lower odds of HPV and HPV vaccine awareness. Men also had lower knowledge of HPV linkage with cervical cancer. Although the vaccine was initially introduced primarily for women, it has been over a decade since the recommendation for males, suggesting that promotion efforts among men need strengthening. Previous literature had pointed to communication inequalities, also known as the digital divide, which contributed to knowledge gaps among low socioeconomic, rural, underserved, and minority populations.Citation33 Our analysis demonstrated lower HPV and HPV vaccine awareness among African Americans, Asian Americans, and Hispanic adults, consistent with previous findings.Citation34

Social media may be indirectly perpetuating gender and racial disparities. Images on Twitter and Instagram reported an overrepresentation of women in HPV-related posts.Citation12 Men and racial minorities were less likely to be featured on Twitter images, despite having equal or more disease burden compared to women and white individuals.Citation35 In terms of reaching certain key demographics to disseminate vaccine and cancer prevention promotional messages, social media may be a cost-effective strategy to reach both targeted and broad groups of individuals.

Our findings, if confirmed with additional studies, can inform development of interventions using social media as a channel to reach vulnerable populations to spread accurate information about HPV to encourage vaccination. Han, Lee, & Demiris (2019) found that social media interventions targeting racial/ethnic minorities were fruitful in raising cancer awareness.Citation36 A randomized-controlled trial by Glanz et al. (2017) found that pregnant women who were assigned to a social media intervention were more likely to be up-to-date on infant immunizations than those who received usual routine care.Citation37 Social media components included a blog, forum, chat function, and ability to directly ask experts about vaccination to encourage engagement and reinforce the vaccine knowledge,Citation37 highlighting the benefits of multi-component interventions. Interventions that incorporate randomized controlled trials or longitudinal designs can assess the effectiveness of delivering messages on social media on health behaviors as well as the long-term impact of using social media on health behavior.

Given the proliferation of misinformation and its negative impact on vaccine attitudes,Citation10 it is important for public health communication efforts to be proactive in delivering credible, well-timed information instead of reacting and attempting to correct misinformation, which has proved to be difficult.Citation38 Social media campaigns need to combat vaccine hesitancy and misinformation before it begins;Citation39 this is especially salient given the struggle against misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though yet to be developed, the anti-vaccine community has been propagating falsehoods and spreading doubts related to a potential COVID-19 vaccine using social media.Citation40 Though small in size, the vocal anti-vaccine community has employed strategic approaches online to undermine confidence in vaccines. For example, multiple anti-vaccination groups worked in tandem to leave thousands of negative comments when a pediatric practice posted a video promoting HPV vaccination on its Facebook page. Hoffman et al. (2019) found the anti-vaccination responses clustered in distinct subgroups (i.e. trust, alternatives, safety, and conspiracy).Citation41 Anti-vaccine proponents employed varied arguments, necessitating targeted interventions in place of generic public health messages that encourage vaccination.

Additionally, the information presented by credible sources need to reflect the needs and preferences of its intended audiences. In other words, the message content needs to be aligned with the recipients, with consideration of health literacy, numeracy, language, and culture.Citation42,Citation43 Messages that are easy to understand incorporating faces and voices of the target audience are more likely to be effective than a one-size-fits-all approach to health communication.Citation35,Citation44 Lack of timely, relevant information may lead users to seek information from less credible sources, which may contribute to vaccine hesitancy. In addition to online channels, healthcare providers are critical in the multi-level efforts to spread correct HPV information. In addition to raising awareness, healthcare provider (HCP) recommendation is one of the most important factors in HPV vaccine uptake.Citation45 Patient-provider communication needs to be bolstered so that patients seek and trust provider counseling. As HCP recommendation has often been the primary reason for vaccination, providers need to be consistently recommending vaccination for eligible patients. Further, culturally competent care centering around patient care needs to be emphasized in order to foster trust, understanding, and vaccine uptake. In concert with stating benefits of vaccine recommendation (e.g. cancer prevention), actionable next steps need to be provided (e.g. vaccination offer at the time of visit). Motivational interviewing, a patient-centered strategy for behavior change, coupled with direct, easy to understand language underscoring HPV vaccination benefits have demonstrated to be effective recommendation techniques, particularly for vaccine hesitant patients.Citation46 Investing in provider communication strategies, including the use of translators, may alleviate the disparities for racial/ethnic minorities, who frequently cite lower satisfaction of care.Citation47,Citation48 Improved patient-provider communication is critical so that patients receive recommendations from credible sources instead of seeking information online, increasing risk of exposure to false information.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that uses nationally representative data to explore the association of social media use with HPV and HPV awareness among adults with children in the household. Findings from this exploratory examination suggest that social media can potentially influence HPV-associated awareness and highlight low knowledge of non-cervical HPV cancers knowledge among users. As more people turn to social media for general and health-related purposes, users become consumers of a plethora of vaccine-related information, credible or not. Since knowledge is a critical piece in decision-making related to vaccination, it is crucial that users are exposed to correct information. The content and delivery of vaccine messages on social media can shape public knowledge and awareness of HPV, which may influence decision-making.Citation10,Citation49

Lastly, our findings have implications for using social media as a channel for information dissemination. While the benefits of using this medium are numerous, there are associated challenges that need considering as well. First, while our study characterizes different types of social media engagement, further research is needed on why some users prefer certain platforms over others and for which purposes. Some platforms serve as a site of passive content consumption, while other promote active engagement via two-way communication such as social networking sites (e.g. Facebook). In a similar vein, further research is needed on what makes certain content more compelling (i.e. viral) than others and if engagement metrics (i.e. likes or shares) can be leveraged for disseminating vaccine promotional messages. Research has demonstrated the role of malicious actors, such as bots and trolls, which may interfere with public health efforts to reduce vaccine hesitancy,Citation15 adding additional challenges to the constantly evolving nature of social media.

There are several limitations to our cross-sectional study, wherein causality cannot be assessed. First, we were limited in the variables available, which did not include vaccination intention or behavior. Second, since we combined social media behaviors into a composite variable, we were unable to discern which particular behaviors, which were not specifically related to HPV information seeking, may be contributing to HPV awareness. Thus, we were unable to ascertain the specific purpose of respondents’ social media use. Furthermore, we acknowledge that individuals are exposed to health information from multiple sources aside from social media, directly or passively, which may influence their awareness and knowledge of HPV. Hence, findings of the association between increased social media use and increased HPV awareness must be interpreted with caution. Having robust data on factors that influence HPV-related information seeking would enrich study findings and allow for a better understanding of the role social media plays on vaccine decision-making among parents or caregivers. Bivariate analyses (not shown) revealed that social media behaviors were not distinct from one another and thus, frequency and combination of behaviors may be more significant contributors to awareness than an individual behavior. In other words, using various forms of social media may present more opportunities to be exposed to HPV-related information. Further, our findings indicated an association, but did not account for the quality of information that users are exposed to on social media. Knowledge or awareness does not correspond to veracity of information that people are exposed to online. Future research can explore the accuracy of content and the role of misinformation on HPV awareness, vaccine intention, and behavior among parents and guardians of children.

Moreover, future studies can take into account HPV vaccine knowledge and decision-making among respondents who do not use social media (e.g. men, older adults). These adults may not be exposed to health promotional messages and may be subject to increased health disparities. In order to better understand the health-seeking behaviors of these individuals, qualitative studies can identify trusted and used information sources among this heterogeneous group. Questions investigating the preference of source and content of health messages may aid in the development of strategies to reach harder to reach populations. Further, identifying why these users do not use social media for health purposes and preferred communication channels can illuminate how to facilitate behavior adoption among social media non-users such as mobile applications (i.e. mHealth) or telemedicine.

Our study demonstrated that among adults with children in the household, social media users had increased odds of HPV-related awareness compared to non-users, highlighting knowledge gaps of this population. Public health practitioners and healthcare providers need to work in tandem with online efforts to connect individuals with credible information to promote healthy behavior adoption. Of critical importance, health promotion efforts need to be proactive in disseminating accurate information prior to misinformation exposure. Given the ubiquity and increased use of social media, it has potential to be an effective communication tool and platform to combat inequalities in HPV-associated knowledge and morbidities among vulnerable communities. Understanding how social media influences awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine among parents and caretakers of children could inform approaches to increase knowledge, which in turn could influence vaccine uptake, reducing risk for HPV infection and cancer for children and parents of eligible age.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ali Hurtado, Mia Smith-Bynum, and Marie Thoma for their insightful comments on the manuscript.

References

- Stokley S, Jeyarajah J, Yankey D, Cano M, Gee J, Roark J, Curtis RC, Markowitz L. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescents, 2007-2013, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006-2014--United States.MMWR. 2014;63:620–24

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, Yankey D, Markowitz LE, Fredua B, Williams CL, Meyer SA, Stokley S. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years-United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(33):874–82. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6633a2.

- Kaplan AM, Haenlein M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus Horiz. 2010;53(1):59–68. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003.

- Duggan M, Lenhart A, Lampe C, Ellison NB. Parents and social media. Pew Research Center, 2015; 1–37. https://www.pewinternet.org/2015/07/16/parents-and-social-media. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- Fox S. The social life of health information. Pew Research Center. 2014. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/01/15/the-social-life-of-health-information/. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- Briones R, Nan X, Madden K, Waks L. When vaccines go viral: an analysis of HPV vaccine coverage on YouTube. Health Commun. 2012;27(5):478–85. doi:10.1080/10410236.2011.610258.

- Ekram S, Debiec KE, Pumper MA, Moreno MA. Content and commentary: HPV vaccine and YouTube. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32(2):153–57. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2018.11.001.

- Keelan J, Pavri V, Balakrishnan R, Wilson K. An analysis of the human papilloma virus vaccine debate on MySpace blogs. Vaccine. 2010;28(6):1535–40. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.11.060.

- Guidry JPD, Carlyle K, Messner M, Jin Y. On pins and needles: how vaccines are portrayed on Pinterest. Vaccine. 2015;33(39):5051–56. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.064.

- Dunn AG, Leask J, Zhou X, Mandl KD, Coiera E. Associations between exposure to and expression of negative opinions about human papillomavirus vaccines on social media: an observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(6):e144. doi:10.2196/jmir.4343.

- Massey PM, Leader A, Yom-Tov E, Budenz A, Fisher K, Klassen AC. Applying multiple data collection tools to quantify human papillomavirus vaccine communication on Twitter. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(12):12. doi:10.2196/jmir.6670.

- Basch CH, MacLean SA. A content analysis of HPV related posts on Instagram. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018:1–3. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1560774.

- Kearney MD, Selvan P, Hauer MK, Leader AE, Massey PM. Characterizing HPV vaccine sentiments and content on Instagram. Health Educ Behav. 2019;46(2_suppl):37S–48S. doi:10.1177/1090198119859412.

- Keim-Malpass J, Mitchell EM, Sun E, Kennedy C. Using Twitter to understand public perceptions regarding the #HPV vaccine: opportunities for public health nurses to engage in social marketing. Public Health Nurs. 2017;34(4):316–23. doi:10.1111/phn.12318.

- Broniatowski DA, Jamison AM, Qi S, AlKulaib L, Chen T, Benton A, Quinn SC, Dredze M. Weaponized health communication: Twitter Bots and Russian trolls amplify the vaccine debate. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1378–84. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567.

- Margolis MA, Brewer NT, Shah PD, Calo WA, Gilkey MB. Stories about HPV vaccine in social media, traditional media, and conversations. Prev Med. 2019;118:251–56. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.11.005.

- Kontos EZ, Emmons KM, Puleo E, Viswanath K. Contribution of communication inequalities to disparities in human papillomavirus vaccine awareness and knowledge. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(10):1911–20. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300435.

- Ortiz RR, Smith A, Coyne-Beasley T. A systematic literature review to examine the potential for social media to impact HPV vaccine uptake and awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about HPV and HPV vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1465–75. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1581543.

- Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, Markowitz LE, Thomas CC, Thompson TD, Razzaghi H, Saraiya M. Human papillomavirus–associated cancers — United States, 2008–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(26):661–66. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6526a1.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2019. 2019. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2019/cancer-facts-and-figures-2019.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, Noone A-M, Markowitz LE, Kohler B, Eheman C, Saraiya M, Bandi P, Saslow D, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)–associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(3):175–201. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs491.

- Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Fakhry C. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus–positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. JCO. 2015;33(29):3235–42. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6995.

- Jeudin P, Liveright E, Del Carmen MG, Perkins RB. Race, ethnicity, and income factors impacting human papillomavirus vaccination rates. Clin Ther. 2014;36(1):24–37. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.11.001.

- Niccolai LM, Mehta NR, Hadler JL. Racial/ethnic and poverty disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination completion. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4):428–33. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.032.

- De P, Budhwani H. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine initiation in minority Americans. Public Health. 2017;144:86–91. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2016.11.005.

- Daniel-Ulloa J, Gilbert PA, Parker EA. Human papillomavirus vaccination in the United States: uneven uptake by gender, race/ ethnicity,and sexual orientation. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):746–47. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.303039.

- Landis K, Bednarczyk RA, Gaydos LM. Correlates of HPV vaccine initiation and provider recommendation among male adolescents, 2014 NIS-Teen. Vaccine. 2018;36(24):3498–504. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.075.

- Gelman A, Miller E, Schwarz EB, Akers AY, Jeong K, Borrero S. Racial disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination: does access matter? J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(6):756–62. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.002.

- Health Information National Trends Survey. Cycle 5 methodology report. 2018. https://hints.cancer.gov/docs/methodologyreports/HINTS5_Cycle_2_Methodology_Report.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- Blake KD, Ottenbacher AJ, Finney Rutten LJ, Grady MA, Kobrin SC, Jacobson RM, Hesse BW. Predictors of human papillomavirus awareness and knowledge in 2013: gaps and opportunities for targeted communication strategies. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(4):402–10. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.024.

- Wheldon CW, Krakow M, Thompson EL, Moser RP. National trends in human papillomavirus awareness and knowledge of human papillomavirus–related cancers. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(4):e117–e123. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.005.

- Boakye EA, Tobo BB, Rojek RP, Mohammed KA, Geneus CJ, Osazuwa-Peters N. Approaching a decade since HPV vaccine licensure: racial and gender disparities in knowledge and awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(11):2713–22. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1363133.

- Viswanath K, Ackerson LK. Race, ethnicity, language, social class, and health communication inequalities: a nationally-representative cross-sectional study. Plos One. 2011;6(1):e14550. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014550.

- Becerra MB, Avina RM, Mshigeni S, Becerra BJ. Low human papillomavirus literacy among Asian-American women in California: an analysis of the California health interview survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020 January 13;7(4):678–86. Published online. doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00698-7.

- Lama Y, Chen T, Dredze M, Jamison A, Quinn SC, Broniatowski DA. Discordance between human papillomavirus Twitter images and disparities in human papillomavirus risk and disease in the United States: mixed-methods analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(9):e10244. doi:10.2196/10244.

- Han CJ, Lee YJ, Demiris G. Interventions using social media for cancer prevention and management: a systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(6):E19–E31. doi:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000534.

- Glanz JM, Wagner NM, Narwaney KJ, Kraus CR, Shoup JA, Xu S, O’Leary ST, Omer SB, Gleason KS, Daley MF, et al. Web-based social media intervention to increase vaccine acceptance: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):6. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-1117.

- Hansen PR, Schmidtblaicher M, Brewer NT. Resilience of HPV vaccine uptake in Denmark: decline and recovery. Vaccine. 2020;38(7):1842–48. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.12.019.

- Vorsters A, Van Damme P. HPV immunization programs: ensuring their sustainability and resilience. Vaccine. 2018;36(35):5219–21. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.06.066.

- Roose K. Get ready for a vaccine information war. New York Times. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/13/technology/coronavirus-vaccine-disinformation.html

- Hoffman BL, Felter EM, Chu K-H, Shensa A, Hermann C, Wolynn T, Williams D, Primack BA. It’s not all about autism: the emerging landscape of anti-vaccination sentiment on Facebook. Vaccine. 2019;37(16):2216–23. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.03.003.

- Britigan DH, Murnan J, Rojas-Guyler L, Qualitative Study A. Examining latino functional health literacy levels and sources of health information. J Community Health. 2009;34(3):222–30. doi:10.1007/s10900-008-9145-1.

- Diviani N, van den Putte B, Meppelink CS, van Weert JCM. Exploring the role of health literacy in the evaluation of online health information: insights from a mixed-methods study. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):1017–25. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2016.01.007.

- Dela Cruz MRI, Tsark JAU, Chen JJ, Albright CL, Braun KL. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination motivators, barriers, and brochure preferences among parents in multicultural Hawai‘i: a qualitative study. J Canc Educ. 2017;32(3):613–21. doi:10.1007/s13187-016-1009-2.

- Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, Trucks E, Hanchate A, Gorin SS. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine. 2015;33(9):1223–29. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.021.

- Dempsey AF, O’Leary ST. Human papillomavirus vaccination: narrative review of studies on how providers’ vaccine communication affects attitudes and uptake. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):S23–S27. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.001.

- Clough J, Lee S, Chae DH. Barriers to health care among Asian immigrants in the United States: a traditional review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(1):384–403. doi:10.1353/hpu.2013.0019.

- Lee C, Ayers SL, Kronenfeld JJ. The association between perceived provider discrimination, health care utilization, and health status in racial and ethnic minorities. Ethn Dis. 2009;19:330–37.

- Ahmed N, Quinn SC, Hancock GR, Freimuth VS, Jamison A. Social media use and influenza vaccine uptake among White and African American adults. Vaccine. 2018;36(49):7556–61. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.049.

Appendix

Table A1. Logistic regressions estimating HPV, HPV vaccine awareness, and cervical cancer knowledge stratified by gender

HPV: Human papillomavirus

*<.05; **<.01; ***<.001

Table A2. Logistic regressions estimating HPV and HPV vaccine awareness stratified by race/ethnicity

HPV: Human papillomavirus

*<.05; **<.01; ***<.001