ABSTRACT

We aimed to describe the impact of pertussis on adolescents, adults, and older adults over 2007–2018 in selected Latin American countries by reviewing the literature. We searched the Medline, Embase, Scopus, LILACS, Scielo, Google Scholar, CAPES Journals Web-portal, and Cochrane databases for observational epidemiological studies, clinical trials, and systematic reviews of primary studies. Data were extracted and analyzed for all individuals aged ≥10 years. Of 6,891 studies identified only 25 were eligible. Studies were conducted in Brazil (14), Argentina (4), Colombia (4), Mexico (2) and Chile (1). Epidemiological data among target population were limited. No studies clearly assessed the status of asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic B. pertussis carriers in these age groups. Among all pertussis cases identified, the percentage of patients ≥10 years-old ranged between 2.1% and 66.7% depending on country and sample characteristics. The definition of cases, diagnostic methods, and age groups were not consistent across studies.

Focus on patient section

What is the context?

Pertussis (whooping cough; Bordetella pertussis) is a vaccine-preventable, highly infectious disease transmitted rapidly through coughing, sneezing, and speaking.

Although considered a childhood disease, pertussis is increasingly recognized as an important cause of infection and respiratory disease in adolescents, adults, and older adults.

Diagnosing adolescents and adults with pertussis is however challenging due to asymptomatic clinical presentation and lack of sensitive diagnostic tools.

Adolescents and adults may be carriers of the B pertussis pathogen and may pass on the pathogen to unimmunized or partially immunized naïve newborns and children, the population most at risk for complications and death

What is new?

This review consolidates what is known about the distribution of the pertussis disease among adolescents and adults in some Latin American countries, filling the knowledge gap of the epidemiology of the disease in this population.

Diagnostic tools need to be standardized and surveillance systems need to be improved to more accurately estimate the burden of pertussis in Latin America.

Prevention strategies such as vaccination could be applied in adolescents and adults at risk as a prevention measure.

What is the impact?

Epidemiological evidence is essential to assess the health risk of pertussis among pregnant women, adolescents and adults, such as healthcare professionals working with childcare, also to monitor its impact among the most vulnerable populations (newborns and children).

This is key in defining effective health service needs and strategies, including vaccines that can prevent pertussis.

Introduction

Pertussis (whooping cough; Bordetella pertussis) is a vaccine-preventable, highly infectious disease transmitted rapidly through coughing, sneezing, and speaking.Citation1–3 Infection with the human-restricted gram-negative bacterium B. pertussis is initiated by the binding of the bacterium to tracheal and nasopharyngeal epithelium.Citation1,Citation2

The incubation period is between 7 to 10 daysCitation1,Citation3 and can last up to four weeks in some patients.Citation3 Pertussis generally develops in three phases:Citation2,Citation3 1) a catarrhal phase lasting one to two weeks,Citation2,Citation4 with mild respiratory symptoms, progressing to a gradual increase in cough; 2) a paroxysmal stage,Citation1,Citation2,Citation4 lasting 2 to 10 weeks, evolving under normal temperature and occasionally low fever, with paroxysms of dry cough, difficulty in breathing, often associated with cyanosis and apnea in children <1 year, which can lead to many complications and even death; and 3) a convalescence phase, characterized by a gradual decrease in the frequency, duration, and severity of cough that persists two to six weeks, and may extend to months.Citation1,Citation3,Citation4

Although pertussis has mainly been considered a childhood disease, currently it is recognized as an important cause of infection and respiratory disease in adolescents, adults, and older adults.Citation3,Citation5 Recognizing the disease in adolescents and adults is important, considering that these age groups may be asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic carriers of B. pertussis and may transmit the pathogen to unimmunized or incompletely immunized newborns and children.Citation3,Citation4,Citation6–9 Because of a progressive waning of immunity, pertussis could occur in adolescents and adults even when there is a history of complete immunization or natural disease in childhood.Citation3,Citation10 Despite the well-accepted definition of casesCitation1 underreporting and misdiagnosis, particularly among adolescents and adults, is a problem worldwide.Citation12–14 Adolescents and adults may present atypical symptoms limited to mild or prolonged non-distinctive cough, but they may also suffer severe symptoms such as sleep disturbance, pharyngeal symptoms, weight loss, sneezing attacks, sinus pain, sweating, and headaches.Citation2

Still, data on the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of the disease in adolescent and adult populations are limited.Citation15,Citation16 Furthermore, findings suggest that pertussis incidence in adults aged >50 years old has been increasing over the past yearsCitation3 but it remains significantly underestimated.Citation14

We aimed to systematically review the epidemiology of pertussis disease in adolescents, adults, and older adults over the past decade in selected Latin American countries.

Methods

Following the PRISMA guidelines, we systematically reviewed literature published between 2007 and 2018 reporting on pertussis epidemiological data from in-scope countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Panama, and Uruguay). Countries were considered in-scope countries because they have incorporated in their national immunization program the diphtheria tetanus acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine for adolescents (Argentina, Panamá, Uruguay) and/or the Tdap vaccine as part of their maternal immunization strategy (Brazil, Panama, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Mexico and Colombia) (Supplementary Table 1).Citation4

We aim to review the epidemiology of pertussis disease in adolescents, adults, and older adults (in-scope age groups) between 2007 and 2018 in the in-scope countries (Supplementary methods – Research question). For the age definition of the in-scope age groups, we used the definitions applied by the World Health Organization [WHO]:Citation5,Citation6 adolescents are aged 10–19 years, adults 20–59 years, and older adults ≥60 years.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies were 1) primary studies, such as observational epidemiological studies, clinical trials, and systematic reviews of primary studies; 2) abstracts presented at scientific events and published in their respective proceedings; 3) studies published between 2007 and 2018; and 4) studies in English, Portuguese, or Spanish. Studies were excluded if their focus was not in the selected countries, or did not report epidemiological data (prevalence, incidence, hospitalizations, and mortality) of pertussis in adolescents, adults, and older adults.

Information sources

The search was performed in June 2018 in the following databases: Medline, Embase, LILACS, SciELO, Google Scholar, CAPES Journals Web-portal, and Cochrane library.

Study selection and data collection process

Identified studies were evaluated in two phases by two independent reviewers using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the first phase, the retrieved publications were screened for eligibility based on their titles and abstracts; the studies that passed this first screening stage progressed to the second phase, consisting of full-text content evaluation. Relevant information was extracted from all eligible articles by the two independent reviewers. Disagreement between the two researchers was eventually resolved by a third independent reviewer.

Assessment of the risk of bias

The risk of bias in observational studies was assessed using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) tool or its version adapted for cross-sectional studies.Citation7 The clinical trials and systematic review publications were assessed by the Cochrane bias risk assessment tool and AMSTAR checklist, respectively.Citation8,Citation9

Data extraction and analysis

Data reported with information from individuals >10 years old were considered relevant to our in-scope age group. The data collected included source data for each study, period of data collection, geographical region, cases definition, diagnostic tools, and the percent prevalence, incidence, and mortality due to pertussis in adolescents, adults, and older adults.

Primary measures were summarized and presented descriptively by outcome and country along with risk of bias and quality assessment. Due to considerable methodological differences in the study designs and reporting of outcomes among eligible studies, a meta-analysis was not conducted. All data were analyzed using Excel ™and MedCalc ™software.

Results

Systematic literature review

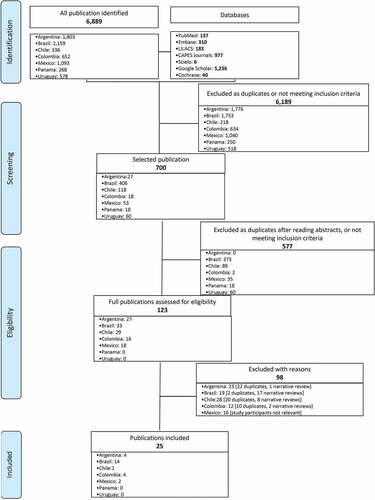

Of the 6,891 references identified, most (89.8%, 6,189/6,891) were excluded at the first screening phase as duplicates (). Of the 125 (18.0%) studies that made it to the second phase, only 25 were found eligible. Most studies (n = 14) were from Brazil, followed by Argentina and Colombia (n = 4 each), Mexico (n = 2), and Chile (n = 1). There were no eligible studies from Panama or Uruguay. Study design was predominantly cross-sectional, with only one case–control study, and one literature review. No clinical trial was included. summarizes the characteristics and findings of these eligible studies.

Table 1. Summary of selected study characteristics, by country, and corresponding information on pertussis cases among adolescents, adults, and older adults

Argentina

Two studies presented national-level data,Citation21,Citation22 and two other regional-level data (Santa Fe and Mar del Plata cities).Citation23,Citation24

National-level data

The national-level studies used pertussis epidemiology data from the national surveillance system covering the period 2002–2011 and reported that among confirmed cases approximately 2.7% were >15 years-old. Between 2004 and 2007, one death due to pertussis was reported in the in-scope age group.Citation10

Regional-level data

The reported frequency of pertussis in the two regional-level studies was twice as high as in the studies with national-level data. Kusznierz et al.Citation11 study included household contacts of children with pertussis visiting a pediatric hospital in the city of Santa Fe, and the Lavayen et al.Citation24 study included positive samples from private health services, primary care centers, municipal hospitals of Mar del Plata and one hospital in Buenos Aires province. In the former study,Citation11 102 (9.5%) of the 1,074 children <14 years-old with pertussis-like clinical characteristics were pertussis-confirmed cases and had 16 suspected for pertussis family contacts. All cases >10 years old were treated as outpatients. Lavayen et al. evaluated 572 pertussis-suspected cases.Citation24 Using different methodologies () the authors confirmed 88 of all suspected cases, five of which (5.7%) were >7 years-old.

Table 2. Definitions of pertussis cases, and diagnostic procedures reported in respective studies

Diagnostic procedures and disease definitions

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was introduced in Argentina for the diagnosis of pertussis in late 2004, while cultures were still considered to be the gold standard for pertussis diagnosis.Citation24 Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) was also used in the Lavayen et al.,Citation10 whilst cultures were still considered to be the reference method in the laboratory diagnosis of pertussis. Study for the serologic detection of B. pertussis antibodies (cutoff value of 93 UI/mL).

Brazil

All 14 studies were published between 2014 and 2017 (). Nine of themCitation25–33 included data from the national surveillance system SINAN (Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação [System for Notifiable Diseases]); two used convenience samples of household contactsCitation34 or healthcare workers;Citation35 each used data from oneCitation36 or tenCitation37 hospital clinics; and oneCitation12 study was a population-based study. We retrieved 11 cross-sectional studies,Citation25,Citation26,Citation28,Citation29,Citation31–35,Citation37,Citation38 one case-control study,Citation13 one case series,Citation3Citation6 and one literature reviewCitation14 (). The pertussis-confirmed cases in the in-scope population reported by all included studies, ranged from 5.2% to 14.0% ().

Only the study by Guimarães et al.Citation28 reported on complications and deaths (152 complications) in adolescents, adults, and older adults, with pneumonia being the most common with 83 (54.6%) cases reported. Two deaths were reported in the same age group, one due to pneumonia and one due to malnutrition.Citation28 Among the confirmed cases there were 73 pregnant women.Citation28

National-level data

One case-controlCitation13 and three cross-sectionalCitation26,Citation28,Citation31 studies reported data from across the country (). The case–control studyCitation13 had a large sample size of 16,078 cases including 1,278 cases >15 years old, strengthening the external validity of the reported pertussis frequency. However, the authors were concerned about the quality of the data and specifically, the way that pertussis cases were defined as the cases reported to SINAN did not specify the duration of the cough. The cross-sectional studies also used the SINAN data covering the period 2000–2014,Citation26,Citation28,Citation31 and they reported proportions of adolescents, adults, and older adults that varied between 8.8% and 13.1% ().

Regional-level data

Nine studiesCitation25,Citation29,Citation32–38 reported regional-level data. Of these, one was the case-series study and the others were cross-sectional studies. Among the confirmed pertussis cases, the frequency of the disease among >10 years-old ranged from 5.2% to 14.0% ().

Diagnostic procedures and pertussis case definitions

Half of the studies used the definition of confirmed cases given by the Brazilian Ministry of Health (MoH) that includes the laboratory, epidemiological, and clinical criteria shown in . For the studies that did not describe the definitions used, it is reasonable to assume that those reporting SINAN dataCitation30–32 followed the MoH definitions because the surveillance guidance is standardized by the MoH. The most common diagnostic procedures were B. pertussis culture and PCR (introduced in routine diagnosis at the National reference Center in 2010,Citation15 and in 2005 in the state of Paraná).Citation29 Serological diagnosis using ELISA (cutoff value of 93 UI/mL) was used only in the study on healthcare workers ().Citation35

Chile

One national-level study,Citation40 reporting 78 years of pertussis epidemiology, was identified (). The diagnostic methods used were not reported (). The authors presented a critical analysis of the epidemiological aspects of the evolution of the disease in the country over the period 1932 to 2010. Based on information from the National Epidemiological Surveillance System, for the period 2001–2010, the incidence rate was 0.41/100,000 in the age group 10–19 years-old, 0.3/100,000 in the age group 20–44 years old, and 0.16/100,000 for those > 45 years-old.Citation40 The corresponding incidence rates during the previous decade (1991–2000) were 0.42/100,000, 0.21/100,000, and 0.07/100,000, showing that pertussis incidence increased among those >20 years old and especially in the older group of >45 years old.Citation40 The authors attributed this increase to several factors, including the increased awareness of the disease with consequent improvements in disease diagnosis, and waning of immunity. The authors further reported a regional dynamic for the disease, given that the increases in pertussis incidence occurred only in the central and mainly southern regions and not in the northern parts of the country.Citation40

Colombia

All four studies included reported regional-level data and were cross-sectional in design. The reported frequencies of pertussis cases in the in-scope population ranged widely from 15% to more than 60% ().

The study of Villareal et al.Citation16 was a field research conducted in 2008 among five family members, in a community affected by an outbreak in February of the same year. An active search was implemented in selected health units to identify additional cases. Probable cases were subjected to laboratory confirmation with either PCR or direct immunofluorescence (DIF).

Only five cases were confirmed in the study, three of which were in our in-scope age group. Because of the study design, selection bias was considered as a limiting factor for the generalizability of the results. Moreover, the authors mentioned that more than half of the probable cases in all age groups had not been reported and that departmental public health laboratories needed to expand their capacity to diagnose pertussis.Citation16

A further study, Montilla-Escudero et al.,Citation17 was conducted during the 2013 outbreak in the department of Antioquia and aimed to assess the correlation between the diagnostic techniques, DIF, PCR, and ELISA. To this end, an active community search for symptomatic contacts of patients with positive DIF results and an active institutional search consisting of a monthly review of surveillance data was conducted and resulted in the selection of 180 probable cases. Nasopharyngeal samples of these cases were analyzed in the public health laboratory of Antioquia, 74% were found positive using either PCR or ELISA, and nearly 16% were from >10 years old individuals (). The authors considered that their results were not robust enough for case confirmation due to the use of the DIF technique for the identification of probable cases and not cultures. They also expressed concern that although PCR is the technique recommended by the official guidelines for the diagnosis of pertussis, 33 of the 35 public health laboratories had not implemented the method, and that firma diagnosis could be provided only by the National Reference Laboratory, therefore compromising the surveillance capacity of the country in the event of an outbreak.Citation17

Ulloa-Virgüez et al. also carried out research in the Department of Antioquia just before the 2013 outbreak.Citation18 They reported that the year 2012 was marked by the highest incidence rate of pertussis in all age groups. They also reported that in the age group 15–44 years-old, the prevalence of the disease was 11.6%, while in those >44 years-old it was 3.4%.Citation18 The authors commented that the apparent resurgence of the disease was in fact due to improvements in diagnosis and surveillance. They also suggested that there was a change in the epidemiology of the disease because of its appearance in adolescents and adults as a result of immunity waning after vaccination.Citation18

In the study carried out in the city of Cali, Astudillo et al. focused on household contacts of suspected pertussis cases (n = 24).Citation19 All infected children had a contact who was also infected, with few symptoms and limited resources to diagnose pertussis. However, using PCR, 33 (30.3%) of the 109 household contacts were found positive for pertussis, of which 22 (66.7%) were in our in-scope age group (25 to >65 years old).Citation19

Diagnostic procedures and pertussis case definitions

Definitions of confirmed pertussis cases varied between studies due to type of diagnosis test performed (). PCR was reported in all studies as a diagnostic method, following DIF in two studies. Cultures and ELISA had also been used for diagnosis.

Mexico

Of the two cross-sectional studies included, Conde-Glez et al.Citation45 used samples obtained from the Nationa Health and Nutritional Survey, and Aquino-Andrade et al.Citation46 used data from 11 hospitals, four in Mexico City and six across the country. The definition of a confirmed case and diagnostic methods differed between the two studies (). The pertussis-confirmed cases in the in-scope population ranged from 19.6% to 65.3% ().

Using ELISA in 3,984 study participants, Conde-Glez et al.Citation45 developed a seroprevalence survey to measure the levels of anti-B. pertussis antibodies among different social strata. The participant’s ages ranged from one to 95 years old, and the seropositivity rates for anti-B. pertussis antibodies were 40.4% in the 10–19 years old, and 46.3% in the >20 years old. The authors observed a statistically significant difference in the levels of seroprevalence between children, adolescents and adults. They attributed the high presence of infection in adolescents and adults to waning of immunity, and in older adults to acute infection as these adults had most likely not received vaccination earlier in life.Citation45

The focus in the study by Aquino-Andrade et al.Citation46 was on contacts of infected children. Among the 434 contacts enrolled, 85 (19.6%) were found positive for pertussis using PCR. Among the positive contacts, the mothers had the highest positivity rates for B. pertussis (41 of 85, 48.2%) with a median age of 24 years (range 16–42 years). Among the 71 fathers, 12 (16.9%) were positive for B. pertussis and had a median age of 25 years (range 17–45 years). Of all contacts, 38.7% had an unknown result indicating possible colonization with B. pertussis and a potential source of transmission. Most of the positive contacts were symptomatic (77.6%).Citation46

Pertussis epidemiological data by age groups

In summary, among confirmed pertussis cases, the frequencies in the overall in-scope population aged >10 years ranged widely from 2.1% to 66.7% depending on country and sample characteristics (). Most studies did not report data by age group (). Only 11 out of the 25 studies included in the systematic review reported data that could be grouped into the three age categories of adolescent, adult, and older adult, although not always with the same cutoffs in the age-group definitions (). Based on these limited data, the lowest frequency of pertussis was observed in the older adult group, and highest in the adult group. Despite this, the discrepancies in population characteristics and the small sample sizes are a limitation on the age-group comparisons and conclusions.

Risk of bias quality assessment

Risk of bias was performed for the full-text journal publications (n = 25) using the NOS tool for the 17 cross-sectional studies included and an adapted version for the other observational designs. The overall risk of bias of individual studies was considered low, with scores varying from 2 to 5 according to the instrument scale. The evidence found was considered limited and of low quality. In addition, the overall risk of bias was considered high due to a high design-specific source of bias which can be attributed to the nature of observational studies, specifically those using passive surveillance and laboratory data.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

The present systematic review shows that there is a serious deficit of epidemiological data among adolescents, adults, and older adults in selected Latin American countries. Likewise, there are no studies that clearly assess the status of asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic B. pertussis carriers in these specific groups. Only 7 of the 25 papers reported national-level epidemiological data on pertussis. Even for Brazil, the country with the most publications retrieved, only four studies reported on national-level data related to the in-scope population. This reflects that pertussis surveillance in the review’s in-scope countries was possibly not focused on or suitable for the identification of these age groups.

Among all cases, the frequency of B. pertussis was different between countries and varied widely, among patients depending on country and sample characteristics. This observation applies to the overall in-scope population of individuals aged >10 years and also to the in-scope age-groups. Some studies that were based on secondary national surveillance databases reported lower proportion of pertussis cases among adolescents and adults than studies using regional data, as evidenced from studies in Argentina,Citation21–24 Mexico,Citation46 and Colombia.Citation17,Citation18 Additionally, studies investigating contacts of positive cases showed a high prevalence of pertussis isolation among people >15 years old.Citation44,Citation46 Also, Berezin et al.Citation34 observed that mothers (11.8%) and fathers (12.9%) were the groups of adults with the highest positive rates among contacts of children positive for pertussis and highlighted that contacts with index cases can be positive for B. pertussis regardless of the presence of symptoms. In an outbreak investigation in Colombia, even without the laboratorial diagnosis, pertussis cases were confirmed based on the epidemiological link observed between confirmed cases among children and the adults, showing potential transmission across all ages.Citation16 On the other hand, a seroprevalence survey developed in Mexico showed lower prevalence of anti-B. pertussis antibodies among adolescents (10–19 years old: 40.4%) and adults (≥20 years old: 46.3%) when compared to the children antibody levels (1–9 years old: 59.3%) indicating waning immunity among those older age groups.Citation45

The definition of cases was not consistent in the selected studies. Brazilian studies followed the WHO definition for a clinical case (coughing lasting ≥2 weeks with ≥1 symptom of paroxysms, whooping, post-tussive vomiting) and laboratory confirmation (culture, PCR, serological).Citation1 Although WHO does not recommend DIF for pertussis diagnosis, because it may give false positive or false-negative results,Citation20 the method was used in two studies from ColombiaCitation16,Citation18 as an initial indicator of a probable case. The diagnostic procedure used also varied from study to study. PCR is considered the most sensitive method for disease diagnosis and was used in most of the studies with 16 of 25 using this diagnostic approach, but it was not the only technique. Other studies reported using the older method of isolation from a culture, and ELISA. Culture is considered 100% specific for B. pertussis but it loses sensitivity after the second week of infection, increasing the risk of false-negative results,Citation21 and it is not optimally sensitive in adolescents and adults.Citation4,Citation48 Nevertheless, culture was considered the 'gold standard' method in some laboratoriesCitation13,Citation25,Citation38 and was used as a diagnostic method in many (n=11) of the studies included in this review. ELISA was also used as a diagnostic method in parallel to othersCitation24,Citation42 or as the only diagnostic technique.Citation35,Citation45

Some evidence of pertussis in adults outside Latin America

Outside Latin America, underestimation of the disease incidence in populations other than children was also mentioned in publications. A prospective study was conducted in 12 European countries from 2007 to 2010 in 3,104 adults (≥18 years old) visiting a general practitioner due to acute cough lasting ≤28 days.Citation41 On average, 3% were pertussis cases (from 0% to 6.2%, depending on the country).Citation41 In a US study, in the absence of direct incidence estimates, Masseria et al.Citation17 used inferential statistics to estimate the 2006–2010 incidence of pertussis among adults ≥50 years old with cough illness (ICD-9 codes for pertussis, pneumonia, cough, and acute bronchitis), using a private Practitioners’ claims database containing approximately 1 billion entries. The model suggested 2.5% of those 50–64 years old and 1.7% of those ≥65 years old were infected by B. pertussis; the respective average estimated incidences were 202 and 257 per 100,000. The annual incidence of cough illness due to pertussis was predicted to increase over the years, reaching 464 per 100,000 in 2010 (i.e., 94–264 times higher than the country reported incidence for people aged >40 years old). These estimates, depending on the year, were 42–105 times higher than medically confirmed pertussis cases.

In a recent systematic review on the burden of disease and vaccination status in adults >50 years old, Kandeil et al.Citation18 identified only 44 epidemiological studies published worldwide between 2006 and 2016. Most studies were conducted in Europe (n = 18), followed by Australia and New Zealand (n = 10). Two studies were from South America, both from Brazil and are included in the present systematic review.Citation25 Kandeil et al.Citation18 study also made important discussion related to pertussis epidemiology in adults. The author mentioned that, although Torres et al.Citation25 reported an increase in pertussis incidence from 2007 to 2013, it is not possible to infer that this increase affected the age group of people ≥50 years old because the annual incidence was not stratified by age. Kandeil et al.Citation18 also noted that the frequency of <1% confirmed pertussis cases in patients ≥60 years old reported by Guimaraes et al.Citation22 was highly uncertain due to 5 to 6-times rate of underreporting during the study period of 2007–2014.Citation18 Overall, Kandeil et al.Citation18 suggested that the real worldwide prevalence of pertussis in older adults (≥50 years old) is largely underestimated by up to several 1,000-fold, as indicated by seroprevalence data of the clinical and subclinical infections.

Underreporting of pertussis cases among older adults may occur for several reasons.Citation2 Different diagnostic techniques have a direct impact on the number of cases reported. Bacterial culture is specific and sensitive in infants but it is not as sensitive as PCR in diagnosing pertussis in adolescents and adults.Citation19,Citation35 Pertussis in adults may have an atypical course,Citation35 be asymptomatic, or present with milder symptoms than those occurring in children.Citation3 A systematic review and meta-analysis on diagnostic accuracy and clinical characteristics of pertussis-associated symptoms showed that adults without paroxysmal cough or the presence of fever are very unlikely to have pertussis (low specificity for these symptoms).Citation1 Whooping and post-tussive vomiting however indicate that the adult who presents with such symptoms constitutes a suspected case in need for further confirmation.Citation43 Post-tussive vomiting which is a moderately sensitive and specific symptom in children was shown to have, together with whooping cough, a low sensitivity but a high specificity in adults.Citation43 Furthermore, comorbidities in older adults such as chronic respiratory diseases make pertussis symptoms more difficult to detect, and cause delay or missed opportunities for disease diagnosis.Citation18,Citation42,Citation44 A recent analysis of pertussis cases with cough onset between 2001 and 2015, found that 27% of patients ≥65 years old had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 44% of those 12–20 years old had a history of asthma, both higher than the average rate in the US for the same age groups.Citation44

Differences between vaccination policies might also have affected the epidemiological analysis by age group. Country-specific characteristics of immunization programs and time since their introduction should be investigated in future by examining disease prevalence and also vaccine uptake by age group. Evidence comparing the effects of vaccination policies on pertussis prevalence among our in-scope age-groups is not available. Furthermore, our study did not aim to investigate such effects, although we know from data on infants that there is such an association. For example, based on the 2017 Global Pertussis Initiative (GPI) report, the pertussis case fatality rate among infants was decreased in Latin America after the introduction of maternal immunization during pregnancy.Citation45 Argentina was the first of the Latin America countries to introduce free universal maternal immunization during pregnancy in 2012, and in 2014, deaths due to pertussis were 92% lower than in 2011 {Vizzotti, 2015#180}. In Brazil too, pertussis immunization of pregnant women was associated with a 47.7% reduction in non-hospitalized pertussis cases among young infants aged <12 months after introduction of maternal vaccination in 2014.Citation46

Expanding current knowledge on age groups neglected by current literature, which mostly involves hospitalized cases among infants and young children,Citation47 our findings may be used to support efforts to extend vaccination policy in the countries in the region. This is primarily because they show that adolescent and adult pertussis epidemiology has been largely neglected in each in-scope country in terms of disease surveillance, diagnosis, and definition of cases. Acknowledging these shortcomings, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) established the Latin American Pertussis Project (LAPP) in 2009 with the aim of expanding diagnostic capacity and pertussis surveillance.Citation47 Based on the available epidemiologic profile of the country in question, LAPP provides laboratory and epidemiologic training, and technical assistance.Citation47 Evaluation of vaccine policies is the next step followed by surveillance with valuable inputs from sharing of each country’s experiences and best practices.Citation47 With the same aim, the 1st Regional Experts on Infant Vaccination (REIV) meeting in 2018 in Colombia concluded that epidemiological data in the area must be updated, and include risk groups; case definitions should also be harmonized among countries in the region.Citation27 Furthermore, vaccination strategies should strengthen and include missed opportunities such as visits not related to preventive care.Citation48–50 Published findings show that adolescents up-to-date with other vaccinations are more likely to receive an additional age-appropriate vaccine. Thus, simultaneous vaccination is an effective measure to increase vaccine uptake and shows the usefulness of adolescent and adult vaccination platforms.Citation51–53

Study limitations

Many of the selected studies had only a limited description of the epidemiological profile of pertussis among adolescents, adults, and older adults. However, the results to the least suggest the disease prevalence among adolescents and adults is sufficient to perpetuate the circulation of B. pertussis, as they serve as a reservoir for the pathogen, thus placing young children at permanent risk of developing pertussis and suffering the consequences of the disease. The findings of the present review are limited in terms of the absence of age-specific definitions for the disease, the possible underestimation and underreporting of cases, and the variations between countries with regards to disease definition and diagnostic procedures. Standardized methods for disease definitions by age group, and for sample collection, transportation, and diagnostic procedures are mandatory if comparable data within and across the Latin America region are to be produced.Citation54Citation56 Finally, we considered studies from only seven Latin America countries, so our findings cannot be generalized to the Latin America region.

Conclusions

Existing pertussis epidemiological data for adolescents, adults, and older adults of Latin American countries could underestimate the real burden of disease in these populations. Reliable information is required on disease prevalence in a population that is frequently asymptomatic and is a major source of pathogen transmission to children. Our findings showed a need to standardize and apply robust diagnostic tools and have appropriate surveillance systems on a national level. Epidemiological data might be underestimated by the current surveillance methods used by the study countries, such that estimates of prevalence in adolescents and adults may not be reliable enough to serve as a basis for evidence-based policies.

Considering the gaps in knowledge about the disease occurrence among other age groups, preventive strategies such as vaccination among pregnant women, adolescents, adults, and healthcare professionals working in childcare become essential to control the disease transmission among the most vulnerable populations (newborns and children). In the countries where the vaccination with the acellular anti-pertussis vaccine is already implemented for pregnant women, adolescents, and other specific population, an uptake on the vaccination coverage is crucial to avoid the infection to the children.

Additionally, the health authorities should develop and implement improved and age-specific methods for disease diagnosis, in addition of offering appropriate training to physicians who are responsible for disease recognition.

Also, the health authorities should take appropriate action to increase awareness about adolescent and adult pertussis infection in the public and encourage physicians to include the disease in their differential diagnosis.

Finally, there is a clear need for well-designed large-scale observational studies on the epidemiology of pertussis in Latin American countries.

Contributorship

All authors participated in the design or implementation or analysis, and interpretation of the study; and the development of this manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and gave final approval before submission.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

Ariane de Jesus Lopes de Abreu was employed by Shift Gestão de Serviços and reports to a third part employee of the GSK group of companies during the conduction of this study. Bárbara Emoingt Furtado is an employee of the GSK group of companies. Eliana Nogueira Castro de Barros was an employee of the GSK group of companies at the time the manuscript was being drafted. Barbara Furtado hold shares in the GSK group of companies. Eduardo Barbosa Coelho, Altacilio Aparecido Nunes and Anderson Soares da Silva report their institution received funding from the GSK group of companies to complete the work disclosed in this manuscript, as well as funding outside the submitted work.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.9 KB)Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Business & Decision Life Sciences platform for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination, on behalf of GSK. Pierre-Paul Prévot coordinated manuscript development and editorial support. The authors also thank Athanasia Benekou (Business & Decision Life Sciences, on behalf of GSK) for providing medical writing support.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). (https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/burden/vpd/surveillance_type/passive/pertussis_standards/en/).[accessed 29 May 2019]

- Rothstein E & Edwards K. Health burden of pertussis in adolescents and adults. Pediatr Infect Dis J 24, S44–47 (2005).

- McGuiness CB, Hill J, Fonseca E, Hess G, Hitchcock W & Krishnarajah G. The disease burden of pertussis in adults 50 years old and older in the United States: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 13, 32, doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-32 (2013).

- World Health Organization (WHO). (http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/schedules, 2019). [accessed 29 May 2019]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Adolescence: a period needing special attention. Age - not the whole strory., (https://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section2/page2/age-not-the-whole-story.html) [accessed 6 Aug 2020]

- World Health Organization (WHO). World report on ageing and health 2015, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/186463/1/9789240694811_eng.pdf

- Ministerio da Saude. http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/diretrizes_metodologicas_elaboracao_sistematica.pdf. (2012). [accessed 29 May 2019]

- Higgins J, Savovic J, Page M & Sterne J. Current version of RoB 2. (2019).

- AMSTAR Checklist, <https://amstar.ca/Amstar_Checklist.php> (2017). [accessed 29 May 2019]

- Hozbor D, Mooi F, Flores D, Weltman G, Bottero D, Fossati S, Lara C, Gaillard ME, Pianciola L, Zurita E et al. Pertussis epidemiology in Argentina: trends over 2004-2007. Journal of Infection 59, 225–231, doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2009.07.014 (2009).

- Lima DP, Santana FAF & Santos MS. Perfil epidemiológico da coqueluche em Vitória da Conquista - Bahia. C&D -Revista Eletrônica da Fainor 9, 96–110 (2016).

- Willemann MCA, Goes FCS, Araujo ACM & Domingues CMAS. Adoecimento por coqueluche e número de doses administradas de vacinas Pertussis: estudo de caso-controle. 3, 207–214, doi:10.5123/S1679-49742014000200002 (2014).

- Castro HWV & Milagres BS. Perfil epidemiológico dos casos de coqueluche no Brasil nos anos de 2010 a 2014. Universitas: Ciências da Saúde, Brasília 12, 81–90, doi:10.5102/ucs.v15i2.4163 ( 2017).

- Leite D, Blanco RM, Vieira de Melo L, Fiorio C, Martins L, Vaz T, Fernandes S & Sacchi C. Implementation and Assessment of the Use of Real-Time PCR in Routine Diagnosis for Bordetella pertussis Detection in Brazil. Arch Pediatr Infect Dis 22, 196–202 (2014).

- Villareal C, Buelvas D, Morón L, Gómez E & Castillo O. Brote de tosferina, municipio de Sincelejo, Departamento de Sucre, Colombia, 2008. Investigaciones Andina 10, 86–95 (2008).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/clinical/diagnostic-testing/diagnosis-confirmation.html, 2017). [ accessed 29 May 2019]

- Masseria C & Krishnarajah G. The estimated incidence of pertussis in people aged 50 years old in the United States, 2006-2010. BMC Infect Dis 15, 534, doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1269-1 (2015).

- Kandeil W, Atanasov P, Avramioti D, Fu J, Demarteau N & Li X. The burden of pertussis in older adults: what is the role of vaccination? A systematic literature review. Expert Rev Vaccines 18, 439–455, doi:10.1080/14760584.2019.1588727 (2019).

- Governo da Brazil. (http://www.saude.ba.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/2012-Boletim-epidemiol%C3%B3gico-Coqueluche-na-Bahia-n-03.pdf, 2012). [accessed 29 May 2019]

- Kusznierz G, Schmeling F, Cociglio R, Pierini J, Molina F, Ortellao L, Malatini I, Moretti M, Gomez A & Pia A. [Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of children with disease due to Bordetella pertussis in Santa Fe, Argentina]. Rev Chilena Infectol 31, 385–392, doi:10.4067/S0716-10182014000400002 (2014).

- Lavayen S, Zotta C, Cepeda M, Lara C, Rearte A & Regueira M. [Infection by Bordetella pertussis and bordetella parapertussis in cases of suspected whooping cough (2011-2015) in Mar del Plata, Argentina]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica 34, 85–92, doi:10.17843/rpmesp.2017.341.2770 (2017).

- Druzian A, Brustoloni Y, Oliveira S, Matos V, Negri A, Pinto C, Asato S, Urias CS & Paniago A. Pertussis in the central-west region of Brazil: one decade study. Braz. J Infect. Dis 18, 177–180, doi:S1413-8670(13)00276-6 [pii];10.1016/j.bjid.2013.08.006 [doi] (2014).

- Falleiros Arlant L, de CA, Flores D, Brea J, Avila Aguero M & Hozbor D. Pertussis in Latin America: epidemiology and control strategies. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther 12, 1265–1275, doi:10.1586/14787210.2014.948846 [doi] (2014).

- Guimaraes L, Carneiro E & Carvalho-Costa F. Increasing incidence of pertussis in Brazil: a retrospective study using surveillance data. BMC. Infect. Dis 15, 442, doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1222-3 [doi];10.1186/s12879-015-1222-3 [pii] (2015).

- Torres R, Santos T, Torres R, Pereira V, Favero L, M.Filho O, Penkal M & Araujo L. Resurgence of pertussis at the age of vaccination: clinical, epidemiological, and molecular aspects. J Pediatr. (Rio J) 91, 333–338, doi:10.1016/S0021-7557(15)00006-6 [pii];10.1016/j.jped.2014.09.004 [doi] (2015).

- Silva LMN, Graciano AR, Montalvão PSD & França CMJ. O atual e preocupante perfil epidemiológico da coqueluche no Brasil. Rev. Educ. Saúde 5, 21–27 (2017).

- Verçosa RCM & Pereira TS. Impacto da vacinação contra pertussis sobre os casos de coqueluche. Rev enferm UFPE on line, Recife 11, 3410–3418, doi:10.5205/reuol.11088-99027-5-ED.110920171 (2017).

- Fernandes E, Sartori A, de Soarez P, Carvalhanas T, Rodrigues M & Novaes H. Challenges of interpreting epidemiologic surveillance pertussis data with changing diagnostic and immunization practices: the case of the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil. BMC. Infect. Dis 18, 126, doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3004-1 [doi]; 10.1186/s12879-018-3004-1 [pii] (2018).

- Berezin E, de Moraes J, Leite D, Carvalhanas T, Yu A, Blanco R, Rodrigues M, Almeida F & Bricks L. Sources of pertussis infection in young babies from Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Pediatr. Infect. Dis J 33, 1289–1291, doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000000424 [doi];00006454-201412000-00021 [pii] (2014).

- Cunegundes KS, de Moraes-Pinto MI, Takahashi TN, Kuramoto DA & Weckx LY. Bordetella pertussis infection in paediatric healthcare workers. J Hosp Infect 90, 163–166, doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.02.016 (2015).

- Bellettini CV, de Oliveira AW, Tusset C, Baethgen LF, Amantea SL, Motta F, Gasparotto A, Andreolla HF & Pasqualotto AC. [Clinical, laboratorial and radiographic predictors of Bordetella pertussis infection]. Rev Paul Pediatr 32, 292–298, doi:10.1016/j.rpped.2014.06.001 (2014).

- Pimentel A, Baptista P, Ximenes R, Rodrigues L, Magalhaes V, Silva A, Souza N, Matos D & Pessoa A. Pertussis may be the cause of prolonged cough in adolescents and adults in the interepidemic period. Braz. J Infect. Dis 19, 43–46, doi:S1413-8670(14)00176-7 [pii];10.1016/j.bjid.2014.09.001 [doi] (2015).

- Lima M, Estay SA, Fuentes R, Rubilar P, Broutin H & Chowell-Puente G. Whooping cough dynamics in Chile (1932-2010): disease temporal fluctuations across a north-south gradient. BMC Infect Dis 15, 590, doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1292-2 (2015).

- Montilla-Escudero EA, Rojas-Baquero F & Ulloa-Virguez AP. Concordancia entre las técnicas de IFD, PCR y ELISA para determinar la frecuencia de Bordetella parapertussis y Bordetella pertussis en un brote de tos ferina en el departamento de Antioquia (Colombia) en 2013. Infectio 20, 138–150 (2016).

- Ulloa-Virgüez AP. Comportamiento epidemiológico de la tos ferina en Colombia. Rev Cubana Medicina General Integral 31, 42–51 (2015).

- Astudillo M, Estrada V, de Soto MF & Moreno L, A. Infección por Bordetella pertussis en contactos domiciliarios de casos de tosferina en el suroriente de la ciudad de Cali, Colombia 2006-2007. Colombia Médica 42, 184–190 (2011).

- Conde-Glez C, Lazcano-Ponce E, Rojas R, DeAntonio R, Romano-Mazzotti L, Cervantes Y & Ortega-Barria E. Seroprevalence of Bordetella pertussis in the Mexican population: a cross-sectional study. Epidemiol Infect 142, 706–713, doi:10.1017/S0950268813001313 (2014).

- Aquino-Andrade A, Martinez-Leyva G, Merida-Vieyra J, Saltigeral P, Lara A, Dominguez W, Garcia de la Puente S & De Colsa A. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction-Based Detection of Bordetella pertussis in Mexican Infants and Their Contacts: A 3-Year Multicenter Study. J Pediatr 188, 217–223 e211, doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.05.032 (2017).

- Romanin V, Agustinho V, Califano G, Sagradini S, Aquino A, del Valle Juárez M, Antman J, Giovacchini C, Galas M, Lara C et al. Situación epidemiológica de coqueluche y estrategias para su control. Argentina, 2002-2011. Epidemiological situation of pertussis and strategies to control it. Argentina, 2002-2011. Arch Argent Pediatr 112, 413–420 (2014).

- World Health Organization (WHO). 433–460 (http://www.who.int/wer/2015/wer9035.pdf?ua=1, 2015). [accessed 29 May 2019]

- Teepe J, Broekhuizen BD, Ieven M, Loens K, Huygen K, Kretzschmar M, de Melker H, Butler CC, Little P, Stuart B et al. Prevalence, diagnosis, and disease course of pertussis in adults with acute cough: a prospective, observational study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 65, e662-667, doi:10.3399/bjgp15X686917 (2015).

- Kilgore PE, Salim AM, Zervos MJ & Schmitt HJ. Pertussis: Microbiology, Disease, Treatment, and Prevention. Clin Microbiol Rev 29, 449–486, doi:10.1128/CMR.00083-15 (2016).

- Moore A, Ashdown HF, Shinkins B, Roberts NW, Grant CC, Lasserson DS & Harnden A. Clinical Characteristics of Pertussis-Associated Cough in Adults and Children: A Diagnostic Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest 152, 353–367, doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.186 (2017).

- Mbayei SA, Faulkner A, Miner C, Edge K, Cruz V, Pena SA, Kudish K, Coleman J, Pradhan E, Thomas S et al. Severe Pertussis Infections in the United States, 2011-2015. Clin Infect Dis, doi:10.1093/cid/ciy889 (2018).

- Hozbor D, Ulloa-Gutierrez R, Marino C, Wirsing von Konig CH, Tan T & Forsyth K. Pertussis in Latin America: Recent epidemiological data presented at the 2017 Global Pertussis Initiative meeting. Vaccine 37, 5414–5421, doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.007 (2019).

- Friedrich F, Valadao MC, Brum M, Comaru T, Pitrez PM, Jones MH, Pinto LA & Scotta MC. Impact of maternal dTpa vaccination on the incidence of pertussis in young infants. PLoS One 15, e0228022, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228022 (2020).

- Pinell-McNamara V, Acosta A, Pedreira M, Carvalho A, Pawloski L, Tondella M & Briere E. Expanding Pertussis Epidemiology in 6 Latin America Countries through the Latin American Pertussis Project. Emerg. Infect. Dis 23, doi:10.3201/eid2313.170457 [doi] (2017).

- Falleiros-Arlant LH, Torres JR, Lopez E, Avila-Aguero ML, Ulloa-Gutierrez R, Mascarenas A & Brea J. Current regional consensus recommendations on infant vaccination of the Latin American pediatric infectious diseases society (SLIPE). Expert Rev Vaccines 19, 491–498, doi:10.1080/14760584.2020.1775078 (2020).

- Wong CA, Taylor JA, Wright JA, Opel DJ & Katzenellenbogen RA. Missed opportunities for adolescent vaccination, 2006-2011. J Adolesc Health 53, 492–497, doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.009 ( 2013).

- Lee GM, Lorick SA, Pfoh E, Kleinman K & Fishbein D. Adolescent immunizations: missed opportunities for prevention. Pediatrics 122, 711–717, doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2857 (2008).

- Adolescent Immunization Initiative. Rationale for an immunization platform at 16 years of age. National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners NAPNAP), (https://www.napnap.org/sites/default/files/userfiles/for_providers/Adolescent%20Immunization%20Initiative_White%20Paper_2017.pdf) [accessed 29 May 2019]

- Packnett E, Irwin DE, Novy P, Watson PS, Whelan J, Moore-Schiltz L, Lucci M & Hogea C. Meningococcal-group B (MenB) vaccine series completion and adherence to dosing schedule in the United States: A retrospective analysis by vaccine and payer type. Vaccine 37, 5899–5908, doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.06.065 (2019).

- Kurosky SK, Esterberg E, Irwin DE, Trantham L, Packnett E, Novy P, Whelan J & Hogea C. Meningococcal Vaccination Among Adolescents in the United States: A Tale of Two Age Platforms. J Adolesc Health 65, 107–115, doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.02.014 (2019).

- Folaranmi T, Pinell-McNamara V, Griffith M, Hao Y, Coronado.F & Briere E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of pertussis epidemiology in LAtin America and the Caribbean: 1980–2015. Rev Panam salud Publica 41, doi:10.26633/RPSP.2017.102 (2017).

- Ministerio da S. (http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/guia_vigilancia_epidemiologica_7ed.pdf, 2009). [accessed 29 May 2019]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/surv-manual/chpt10-pertussis.html, 2017). [accessed 29 May 2019]