ABSTRACT

The burden of chronic liver disease (CLD) in India is high, particularly among middle-aged men, with nearly 220,000 deaths due to cirrhosis in 2017. CLD increases the risk of infection, severe disease (e.g. hepatitis A virus or HAV superinfection, acute-on-chronic liver failure, fulminant hepatic failure), and mortality. Hence, various countries recommend HAV vaccination for CLD patients. While historic Indian studies showed high seroprevalences of protective HAV antibodies among Indian adults with CLD, the most recent ones found that nearly 7% of CLD patients were susceptible to HAV infection. Studies in healthy individuals have shown that HAV infection in childhood is decreasing in India, resulting in an increasing population of adults susceptible to HAV infection. As patients with CLD are at increased risk of severe HAV infection, now may be the time to recommend HAV vaccination among people with CLD in India.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

What is the context?

Patients with chronic liver diseases have progressive liver deterioration.

Hepatitis A virus infection, while generally mild in childhood, can cause acute liver deterioration in adulthood, and be particularly severe in patients with chronic liver diseases.

We conducted a review of the scientific literature on the status of hepatitis A virus infection and chronic liver diseases in India, including the associated health impacts of liver failure and mortality.

What is new?

We found that chronic liver diseases are common, mostly affecting middle-aged men as a result of hepatitis viruses, alcohol, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Also, the number of children naturally infected by hepatitis A virus is decreasing due to improved sanitation; The population reaching adulthood with acquired immunity is therefore decreasing.

This is likely also the case for patients with chronic liver diseases, putting them at risk of severe disease

What is the impact?

Evidence presented in this review supports the potential benefit of vaccination of individuals with chronic liver diseases.

A potential next step is to recommend hepatitis A virus vaccination for chronic liver disease patients in India, particularly for those without protective antibodies.

This could reduce morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs of hepatitis A virus infection among chronic liver disease patients.

Chronic liver disease (CLD)

Hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E virus (HAV, HBV, HCV, HDV, and HEV) infections and alcohol consumption can cause liver damage, as can obesity, which can result in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). CLD (disease that has lasted for ≥6 months) is a progressive deterioration in liver function, which can lead to fibrosis and cirrhosis.Citation1 Cirrhosis often starts asymptomatically (“compensated cirrhosis”), but can ultimately progress to “decompensated cirrhosis”, during which complications of liver dysfunction and portal hypertension manifest (e.g. ascites, jaundice, variceal bleeding).Citation2 Once a patient has decompensated cirrhosis, their survival will likely only be around 3–5 years.Citation3 In 2017, there were an estimated 1.5 billion cases of cirrhosis and other CLDs globally.Citation4 Liver cirrhosis was the 11th and 26th leading cause of disability-adjusted life years in men and women, respectively;Citation5 the 13th leading cause of life years lost;Citation6 and, along with other CLDs, resulted in over 1.3 million deaths in 2017.Citation6

Early treatment of patients with CLD is important. The goals of treatment are to stop disease progression (generally by managing the underlying cause, e.g. antivirals, alcohol abstinence) and to manage complications (e.g. portal hypertension, hepatorenal syndrome, bleeding esophageal varices, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatocellular carcinoma).Citation1 Ultimately, patients may require a liver transplant, which is the second commonest major organ transplantation.Citation7

Increased risk of severe infection

Patients with cirrhosis have a compromised immune system and are known to be at increased risk of bacterial infection,Citation8–12 and those who become infected have a nearly 4-fold higher risk of death compared with uninfected people with cirrhosis.Citation2 Given the effect of cirrhosis on the immune response, such patients may also be at increased risk of HAV infection. Although we could not find any confirmation of this, patients with CLD certainly appear to be at increased risk of developing more severe HAV disease if they have superimposed HAV disease.Citation13–15 For example, in an outbreak of >300,000 HAV cases in China, mortality was 5.6-fold higher among those with HAV infection superimposed on underlying HBV infection than in those with HAV but without HBV.Citation15 Acute HAV infection in patients with CLD can also result in acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), which is associated with high rates of mortality.Citation16

Patients with CLD are also at increased risk of developing fulminant hepatitis,Citation13,Citation17 also known as fulminant hepatic failure (FHF). In an Italian study, 595 adults (29.1 ± 9.8 years) with chronic HBV or HCV (without HAV antibodies) were enrolled during 1990–1997.Citation18 Of these, 27 (4.5%) acquired HAV superinfection (10/163 of those with chronic HBV and 17/432 of those with chronic HCV). FHF developed in 0/10 chronic HBV patients and 7/17 chronic HCV patients, 6/7 of whom died. None of 191 controls (without CLD) who presented with acute HAV developed FHF.Citation18 While this study implies that patients with chronic HBV are not at risk of FHF after HAV superinfection, results from a small Canadian study show that those with chronic HBV can have FHF after HAV superinfection. In the Canadian study, 4/60 cases of FHF during 1991–1997 were due to HAV.Citation19 Three of these patients had CLD (2 chronic HBV infection; 1 alcoholic cirrhosis), and all 3 died (13–35 days after admission); the patient without CLD survived.Citation19

HAV vaccination recommendations in patients with CLD

The United States (US) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends a 2-dose series of HAV or a 3-dose series of HAV+HBV vaccinations for all patients with CLD, including those with HBV, HCV, cirrhosis, NAFLD, alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis, or alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase level >2 the upper limit of normal.Citation20 Similarly, in the United Kingdom (UK), patients with various chronic liver conditions are recommended to receive HAV vaccination.Citation21

Two types of HAV vaccine are availableCitation22 – live attenuated and inactivated – of which only the latter is appropriate for immunocompromised patients such as those with CLD. The World Health Organization (WHO) has endorsed that inactivated HAV vaccines are well tolerated by patients with mild-to-moderate CLD.Citation17 It is recommended that HAV vaccination should be given as early as possible after CLD diagnosis for maximum efficacy and safety.Citation13,Citation14

Situation in India

Burden and changing etiology of CLD

In a multicenter prospective study conducted in different parts of India, 1.3% of nearly 21 million patients who attended 11 hospitals during February 2010 to January 2013 had liver disease.Citation23 One quarter of these patients had a new diagnosis of liver disease, of whom 19.8% had CLD.Citation23 Among these 13,014 patients with newly diagnosed CLD (of whom 4413 [33.9%] had decompensated cirrhosis), mean age was 42.8 ± 14.4 years and the majority (73.0%) were male.Citation23 The main etiologies were related to hepatitis viruses (54.9%), alcohol (17.3%), and NAFLD (12.8%).Citation23 However, etiology varied widely by region, with HCV being the most common in the North (44.9%), HBV in the East (47.9%) and South (40.5%), alcohol in the North-East (31.9%), and NAFLD in the Central region (43.6%) and the West (39.6%).Citation23 CLD etiologies reported in other studies have varied widely,Citation24–34 likely due to variations by region, population, and over time. The latter has been shown in a study in a tertiary care referral hospital in Eastern India, where etiologies of CLD changed substantially from 2003 to 2011, with alcohol increasing from 22.5% to 42.0% (p = .01), cryptogenic (i.e. unknown cause) decreasing from 44.9% to 25.0% (p = .001), but no significant changes in HBV (mean 22.3%) or HCV (mean 10.9%).Citation35

More recent studies have indicated that NAFLD could be becoming a major cause of CLD in India, with huge numbers of people potentially affected. For example, a study published in 2016 found that 30.7% of adults aged ≥35 years in a rural community in North India had NAFLD on ultrasonography,Citation36 while one published in 2019 reported that 528 (53.5%) of male blood donors (mean age 31 ± 8 years for males and 45 ± 8 for females) in an urban community in North India had NAFLD on ultrasonography.Citation37

Recent meta-analyses have estimated seroprevalences of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) and anti-HCV to be 1.46%Citation38 and 0.44–0.88%,Citation39 respectively in India. Based on a population of approximately 1.38 billion,Citation40 this would equate to approximately 20 million people in India having chronic HBV infection and around 6–12 million having chronic HCV infection, meaning that large numbers of people are potentially at risk for FHF, which has a very high mortality rate among patients with CLD.Citation18,Citation19 However, these numbers are dwarfed by the potential number of people with NAFLD, which, based on the two above-mentioned studiesCitation36,Citation37 and the adult Indian population,Citation40 could equate to hundreds of millions of adults with NAFLD in India. While we were unable to find data on the prevalence of alcoholic liver disease in India, given that 18% of liver-related deaths in India were due to alcohol,Citation41 there are likely also many millions of people with alcoholic liver disease in India.

Mortality

In India, deaths due to cirrhosis nearly doubled – from 110,091 to 217,896 – between 1990 and 2017 (although there was little change in the age-standardized mortality rate).Citation42 In 2017, 16.5% of global cirrhosis deaths (217,896 of 1,322,868) were in India.Citation42

Mortality rates vary among patients with CLD. For example, those with alcoholic cirrhosis had higher 1-month mortality than those with nonalcoholic cirrhosis (9.8% vs. 3.2%) in a single-center study from North East India.Citation43 In that study, patients with alcoholic versus nonalcoholic cirrhosis were more often male (97% vs. 64%) and had more advanced disease (based on various parameters).Citation43 The rates of death or orthotopic liver transplantation within 1 year are even higher among those with a first episode of decompensation (most common presentations among 110 Indian patients with cirrhosis: overt ascites [57.3%], ultrasound-detected ascites [22.7%], and hepatic encephalopathy [13.6%]), occurring in 22.2%, 28.0%, and 20.0% of these patients, respectively.Citation33 In an Indian retrospective study of 392 patients (median [range] age 50 [14–87] years; 80% male) who had died of liver-related causes (except liver metastasis from non-hepatic cancers), the most common causes of liver-related death were alcohol (30.1%), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis/cryptogenic (23.2%), hepatotropic viruses (18.6%), and bacterial/other infections (11.5%).Citation34 Most patients (85.5%) had CLD, and among those with CLD, most (70.7%) had presented with cirrhosis complications (e.g. end-stage liver disease, portal hypertension, sepsis), while 29.3% presented with ACLF.Citation34 Based on data from the WHO, approximately 54% of liver-related deaths in India are due to HBV, 18% due to alcohol, 10% due to HAV or HEV, and 10% due to HCV.Citation41 However, acute hepatitis-related deaths are largely due to HBV (54%) or HEV (37%), with 6% due to HAV and 2% due to HCV.Citation41

ACLF

ACLF (acute decompensation in a patient with CLDCitation16) occurred in 121/3220 (3.8%) patients with cirrhosis and acute HAV or HEV admitted to a hospital in Lucknow during 2000–2006.Citation32 The mean age of those with ACLF was 36.3 ± 18.0 years and 70.2% were male.Citation32 Clinical features included jaundice (100%), ascites (78.5%), coagulopathy (77.7%), encephalopathy (55.4%), hyponatremia (41.3%), renal failure (35.5%), and sepsis (33.9%).Citation32 ACLF was due to HEV in 66.1%, HAV in 27.3%, or both in 6.6%; the underlying CLD was mainly cryptogenic (36.4%), HBV (30.6%), or alcohol (10.7%).Citation32 Three-month mortality among these patients with ACLF was high (44.6%).Citation32 In another retrospective study, which included 1049 consecutive patients with ACLF (mean age 44.7 ± 12.2 years; 81.3% male) conducted in 10 tertiary centers from across India during 2011–2014, the most common precipitants of ACLF were alcohol consumption (35.7%), viral superinfection/flare (HAV, HBV, or HEV) (21.4%), and sepsis (16.6%).Citation29 The underlying CLD was mainly alcohol (56.7%), cryptogenic (19.4%), or HBV/HCV (15.9%). During a median (range) hospital stay of 8 (4–14) days, 42.6% of patients died.Citation29 In a single-center study in Eastern India (2012–2014), the most common precipitants of acute decompensation among 123 patients with ACLF (mean age 45.8 ± 12.1 years; 88.6% male) were recent alcohol intake (42.3%) and bacterial infection (36.6%).Citation44 Three-month mortality was very high (71.3%), more so in alcoholics than nonalcoholics (81.1% vs. 55.9%; p = .01).Citation44 Lastly, among 64 patients (median age 44 years; 82.8% male) with ACLF in a hospital in Hyderabad, 2015–2016, the main precipitants were infection (43.8%) and alcoholism (37.5%). Twenty-eight day mortality was high (43.8%).Citation45

Susceptibility of Indian CLD patients to HAV

Nine out of ten old studies from India (carried out up to 2007)Citation25–28,Citation30,Citation31,Citation46–48 found that nearly all patients with CLD/cirrhosis (93.2–99.0%) had evidence of past infection with HAV (as shown by HAV-immunoglobulin G or HAV-IgGCitation49 or anti-HAV antibodies), as did most healthy controls (71.2–100%) (). The study by Khanna et al.,Citation50 however, reported a much lower rate of HAV-IgG among patients with cirrhosis (60.6%), possibly because they only included patients from the upper middle or upper socioeconomic classes. All of their seronegative CLD patients were vaccinated against HAV.Citation50 The authors of most of the other studies suggested that CLD patients did not routinely require HAV vaccination (as most were already immune),Citation25,Citation27,Citation28,Citation30,Citation31,Citation46–48 while opinions on testing for HAV antibodies before potential vaccination were mixed (see ).Citation25,Citation31,Citation48

Table 1. Seroprevalence studies showing evidence of previous HAV infection (HAV-IgG or anti-HAV) in patients in India with CLD (or specifically with cirrhosis), listed chronologically

However, most of these studies are old, only including patients until 2007 at the latest and, as will be discussed further below, the epidemiology of HAV is changing in India, with declining HAV infection during childhood and subsequent increasing susceptibility in adulthood. It should also be noted that, in the two latest studies in ,Citation25,Citation48 which included patients during the mid 2000s, nearly 7% of CLD patients did not have anti-HAV/anti-IgG antibodies and were therefore susceptible to HAV infection. As suggested by Radha Krishna et al. in 2009Citation32 – based on their study that included 21 adults with ACLF due to HAV – this advice may now be outdated. In a more recent study (2011–2014), 21.4% of ACLF cases were due to HAV, HBV, or HEV superinfection, but unfortunately, the authors did not report results separately for HAV.Citation29

Changing HAV endemicity in India

If HAV is encountered during early childhood, the resultant hepatitis is generally mild, causing no symptoms or nonspecific symptoms (e.g. fever, malaise, diarrhea)Citation51 and providing long-term immunity against HAV.Citation52 However, if HAV is encountered for the first time in adulthood, most people will have symptoms (e.g. jaundice, pain), and it is associated with a mortality rate of around 1%.Citation51 HAV is also significantly more likely to result in more severe disease with increasing age.Citation53 Historically, many people in India were exposed to HAV during childhood, resulting in life-long protection.Citation52 However, with improved sanitation and hygiene, children are becoming less likely to be exposed to HAV, resulting in increasing number of adolescents and adults who are at risk of infection, and a paradoxical increase in morbidity and mortality due to HAV.Citation51,Citation52,Citation54,Citation55 Thus, and taking into account the high heterogeneity across the Indian continent, India is now thought to be shifting from high to intermediate HAV endemicity.Citation51,Citation54 This situation is particularly challenging, as in high HAV endemicity areas, most children are exposed, resulting in mild disease and lifelong immunity, while in low endemicity areas, the chance of exposure in adulthood is low.Citation54 However, with intermediate HAV endemicity, the chance of childhood exposure is reduced, leaving more adults at risk of more severe disease.Citation54

Declining HAV immunity in India

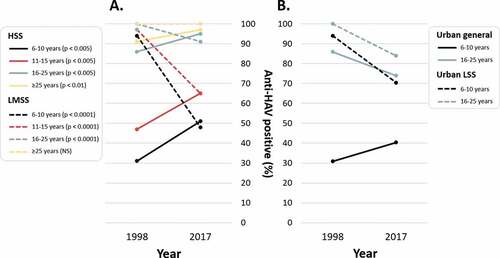

Various serological studies have reported that the proportion of healthy Indian people with seroprotective anti-HAV antibodies (i.e. previous HAV infection) has fallen over time.Citation26,Citation56–59 For example, Arankalle et al.Citation56 reported that anti-HAV positivity decreased significantly from 1982 to 1998 among children from urban high socioeconomic populations (age 6–10 years: ~86% to 30.9%; age 11–15 years: ~94% to 46.9%; combined age p < .00001), but not in adults or urban lower middle socioeconomic populations. Das et al.Citation57 reported that HAV-IgG seropositivity fell from 98.0% in 1982Citation60 to 54.1% in 1998 among those aged 15–24 years and from 98.6%Citation60 to 58.7% among those aged 25–34 years (both p < .05). Hussain et al.Citation26 reported that 71.2% of healthy subjects were positive for HAV-IgG in 1999–2003, much lower than the 94.8% reported in subjects in 1982 in an earlier study.Citation60 Gadgil et al.Citation58 found that HAV seropositivity among adult blood donors fell from 96.5% in 2002 to 92.1% in 2004–2005 (p < .01). Recently, Arankalle et al.Citation59 reported that, while HAV seropositivity decreased from 1998 to 2017 among low/middle socioeconomic children and younger adults, it increased during the same time period among high socioeconomic children and adults ().Citation59 This was likely due to HAV vaccination in the high socioeconomic population, although the vaccination status of the participants was not available. also shows that, in 1998, low/middle socioeconomic populations had considerably higher seropositivity (i.e. were much more likely to have had previous HAV infection) than high socioeconomic populations of the same age group, but by 2017, there was very little difference in seropositivity between the two populations.Citation59 Deoshatwar et al.Citation61 have also reported results from the same region (for select age groups) for 2017 and compared them with the same 1998 data as Arankalle et al.Citation59 shows that the changes in seropositivity were less pronounced in the latter study.

Figure 1. Opposing, but converging, trends in HAV susceptibility among (A) higher and lower middle socioeconomic status populations (created based on data from Arankalle et al.Citation59) and (B) urban general and lower socioeconomic status populations (created based on data from Deoshatwar et al.Citation61)

Arankalle et al.Citation59 also reported that 90–95% of 3-month-old infants in both 1995 and 2017 were seropositive for HAV, likely due to maternal antibodies. In 1995, seropositivity fell to 13.6% by age 9 months and then increased to 41.0% by age 15 months, which must have been due to natural infection as none were vaccinated. However, in 2017, seropositivity fell to only 2.2% among unvaccinated infants at age 15 months.Citation59 These studies all support a decrease in natural HAV infection during childhood, resulting in an increase in the number of susceptible adults.

Increasing HAV infection in adulthood

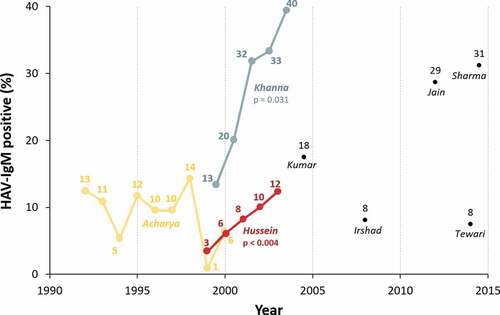

In line with declining HAV seroprotection, some studies have shown an increase in the proportion of acute viral hepatitis cases that are due to HAV over time.Citation26,Citation50 Hussain et al.Citation26 studied 1932 patients with acute viral hepatitis at a tertiary care center in Northern India, of whom 11.4% overall were HAV-IgM positive (indicating current infection). This increased from 3.4% in 1999 to 12.3% in 2003 among adults (Hussain line in ; p < .004); and from 10.6% to 22.0% in children (p < .003). At another tertiary care center in Northern India, Khanna et al.Citation50 reported increasing proportions of acute hepatitis due to HAV from 1999 to 2004 among patients with acute hepatitis aged 13–20 years (27.2% to 61.5%; p = .008), 21–30 years (13.3% to 39.5%; Khanna line in ; p = .031), and >30 years (0% to 17.3%; p = .06).

Figure 2. Increasing acute HAV infection among adults with acute viral hepatitis, created based on data from Acharya et al. 2003,Citation62 Khanna et al. 2006 (middle adult age group used),Citation50 Hussain et al. 2006,Citation26 Kumar et al. 2007 (mainly adults),Citation63 Irshad et al. 2010,Citation64 Jain et al. 2013,Citation65 Tewari et al. 2016,Citation66 and Sharma et al. 2016 (suspected viral hepatitis).Citation67 Further information on these studies can be found in Table 2

Various other Indian studies have reported on the seroprevalence of HAV-IgM antibodies among those with acute viral hepatitis, but have reported no change over time (Acharya line in ),Citation62 or have not studied their evolution over timeCitation63-69 (see and single points in ). While comparisons between studies (particularly single-center studies) should be undertaken with caution, as seropositivity varies widely by socioeconomic status, age, HAV vaccination rates, region, setting, and local outbreaks, there appears to be a slight upward trend in the proportion of adults with acute viral hepatitis who have acute HAV infection ().

Table 2. Seroprevalence studies showing evidence of current HAV infection in patients in India with (suspected) acute viral hepatitis, listed chronologically

The seroprevalence among children varied widely by study, from 16.2%Citation26 to 72.2%,Citation50,Citation66 with little correlation over time. This may relate to the socioeconomic status of the studied populations (which, as shown in , used to have a large impact on seroprevalence, but nowadays, has much less impact), but most studies did not describe this parameter.

Indian HAV immunization recommendations

HAV vaccination is not included in the routine childhood immunization schedule in India.Citation70 However, the Advisory Committee on Vaccines & Immunization Practices (ACVIP) of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) recommends HAV vaccination for all infants, as a single dose of live attenuated vaccine at 12 months or 2 doses of inactivated vaccine at 12 and 18 months of age,Citation51 which can be administered in a private setting paid for by the parents.Citation22 The IAP particularly recommends HAV vaccination for various risk groups, including children with CLD and those who are carriers of HBV and HCV.Citation51

Although the recommendation to vaccinate patients with CLD against HAV has been endorsed by the WHO,Citation17 the Indian National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) does not currently recommend HAV vaccination for adults with CLD in India, as “most adults have already been exposed to and are thus protected”.Citation71 This recommendation is supported by 9/10 old studies from India (carried out up to 2007)Citation25–28,Citation30,Citation31,Citation46–48 (). However, in the current context of changing endemicity it is very unlikely to hold true and therefore we feel that this should now be reexamined.

Indian associations and scientific society recommendations relating to HAV vaccination are detailed in .Citation72–74 The Association of Physicians of India (API) and the Indian Society of Nephrology (ISN) both indicate that patients with CLD who are not immune to HAV, those with other hepatitis virus infections, and patients awaiting or having received a liver transplant are at risk of HAV infection, but do not specifically recommend vaccination.Citation72,Citation73 The ISN, however, says that HAV vaccination “is indicated for all transplant candidates with CLD or those patients of end‑stage renal disease who have chronic hepatitis B or C” due to an increased risk of FHF.Citation73 The Indian Medical Association (IMA) does not mention CLD or other hepatitis infection, but does recommend HAV for adults or children undergoing liver transplantation.Citation74

Table 3. Adult HAV vaccination guidelines from various associations and scientific societies in India

Authors’ recommendations

Based on the currently available evidence of shifting endemicity and increasing HAV susceptibility in adulthood in India, now may be the time to revisit the existing NCDC recommendation that HAV vaccination is not necessary for those with CLD in India.Citation71 Instead, we propose that a recommendation for HAV vaccination of adults with CLD should be considered in India, as is already the case in the US,Citation20 the UK,Citation21 and Sri LankaCitation75 (a near neighbor of India), and also for children with CLD in India.Citation51 While some Indian medical association/society guidelines recognize that seronegative patients with CLD are at increased risk of HAV infection, they do not clearly recommend HAV vaccination.Citation72,Citation73

Up-to-date serological studies among Indian patients with CLD would be beneficial to confirm whether seroprotective HAV antibodies have decreased over time in these patients, in line with what has been shown in healthy people.Citation26,Citation56–59,Citation61 However, awaiting the results of such studies should not be a prerequisite for recommending HAV vaccination among patients with CLD in India.

A more targeted approach, with serological testing prior to HAV vaccination, could be a more cost-effective option than universal HAV vaccination of patients with CLD.Citation25 However, given the limited facilities for serological testing, the associated cost, and the potential for missed opportunity for vaccination if patients do not return after serological testing, this should also not be a prerequisite.

Limitations

This was not a systematic review, so although we included all relevant manuscripts that we could find on PubMed and Embase, there may have been some manuscripts (e.g. those published in Indian journals that are not listed on PubMed or Embase) that we did not manage to capture. Also, India is a large country with high socioeconomic status heterogeneity. As seropositivity rates vary considerably with socioeconomic status, age, HAV vaccination rates, region, setting, and local outbreaks, comparisons between studies from different time periods should be undertaken with caution. Futher, as already discussed, the studies that have assessed the HAV susceptibility of CLD patients are old and, while it is likely that susceptibility among these patients has increased as it has among general adults, this should be confirmed.

Summary and conclusions

The burden of CLD in India is high, resulting in high morbidity and mortality.Citation42 Patients with CLD are at increased risk of severe HAV diseaseCitation13-15,Citation17 and ACLF, which has a very high mortality rate.Citation16,Citation29,Citation32,Citation44,Citation45 Hence, such patients are recommended to receive various vaccinations, including HAV vaccination, in the US,Citation20 the UK,Citation21 and Sri Lanka.Citation75 Old studies from India showed a high seroprevalence of protective HAV antibodies among Indian adults with CLD,Citation25–28,Citation30,Citation31,Citation46–48 although the most recent ones (≤2007) found that nearly 7% of CLD patients did not have protective HAV antibodies and were therefore susceptible to HAV infection. Studies in healthy individuals have shown that HAV infection in childhood is decreasing in India,Citation56–59,Citation76 resulting in an increasing population of adults without protective antibodies, and a higher risk of HAV infection in adulthood.Citation26,Citation50 This is likely also the case among patients with CLD.

Based on seroprovalence data,Citation38,Citation39 millions of people in India likely have chronic HBV or HCV infection. Even more adults could have NAFLDCitation36,Citation37 and, along with an increasing amount of alcoholic liver disease in India,Citation35 this equates to a huge population of people with chronic hepatitis infection and/or CLD. Such people are at higher risk of severe diseaseCitation13,Citation17 (HAV superinfection, ACLF, FHF) and increased mortality.Citation15,Citation18,Citation19

It may, therefore, now be time to reexamine the existing Indian recommendations.Citation71–74 Patients with CLD who do not have HAV antibodies should receive HAV vaccination. This approach could reduce morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs of HAV infection among patients with CLD.Citation77 In situations where antibody testing is not available or practical, CLD patients should not be excluded from HAV vaccination.

elaborates on the findings in a form that could be shared with patients by healthcare professionals.

Author contributions

AA developed the search strategy and searched the databases. All authors participated in the design or implementation or analysis, and the development of the manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and gave final approval before submission.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Business & Decision Life Sciences for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination, on behalf of GSK. Benjamin Lemaire coordinated the manuscript development and editorial support. Jenny Lloyd (Compass Medical Communications Ltd.) provided writing support.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

Anar Andani, Shafi Kolhapure, and Ashish Agrawal are employees of the GSK group of companies. Anar Andani and Shafi Kolhapure hold shares as part of their employee remuneration. Bhaskar Raju declares no financial conflicts of interest. All authors declare no non-financial conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sharma A, Nagalli S. 2020. Chronic liver disease. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available at .nih.gov/books/NBK554597/, accessed April 21, 2020.

- Arvaniti V, D’Amico G, Fede G, Manousou P, Tsochatzis E, Pleguezuelo M, Burroughs AK. Infections in patients with cirrhosis increase mortality four-fold and should be used in determining prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1246–56. 1256 e1241-1245. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.019.

- Hernaez R, Sola E, Moreau R, Gines P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: an update. Gut. 2017;66:541–53. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312670.

- GBD Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7.

- GBD. DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2017;2018(392):1859–922. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32335-3.

- GBD. Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2017;2018(392):1736–88. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7.

- Manzarbeitia C Liver transplantation. Available at https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/431783-print, accessed April 21, 2020.

- Ghassemi S, Garcia-Tsao G. Prevention and treatment of infections in patients with cirrhosis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:77–93. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2006.07.004.

- Tandon P, Garcia-Tsao G. Bacterial infections, sepsis, and multiorgan failure in cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:26–42. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1040319.

- Fiuza C, Salcedo M, Clemente G, Tellado JM. In vivo neutrophil dysfunction in cirrhotic patients with advanced liver disease. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:526–33. doi:10.1086/315742.

- Christou L, Pappas G, Falagas ME. Bacterial infection-related morbidity and mortality in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1510–17. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01286.x.

- Irvine KM, Ratnasekera I, Powell EE, Hume DA. Causes and consequences of innate immune dysfunction in cirrhosis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:293. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00293.

- Reiss G, Keeffe EB. Review article: hepatitis vaccination in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:715–27. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01906.x.

- Keeffe EB. Hepatitis A and B superimposed on chronic liver disease: vaccine-preventable diseases. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2006;117:227–37. discussion 237-228.

- Cooksley WG. What did we learn from the Shanghai hepatitis A epidemic? J Viral Hepat. 2000;7(Suppl 1):1–3. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2893.2000.00021.x.

- Sarin SK, Choudhury A, Sharma MK, Maiwall R, Al Mahtab M, Rahman S, Saigal S, Saraf N, Soin AS, Devarbhavi H, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian pacific association for the study of the liver (APASL): an update. Hepatol Int. 2019;13:353–90. doi:10.1007/s12072-019-09946-3.

- World Health Organization. WHO position paper on hepatitis A vaccines – june 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2012;87:261–76.

- Vento S, Garofano T, Renzini C, Cainelli F, Casali F, Ghironzi G, Ferraro T, Concia E. Fulminant hepatitis associated with hepatitis A virus superinfection in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:286–90. doi:10.1056/NEJM199801293380503.

- Lefilliatre P, Villeneuve JP. Fulminant hepatitis A in patients with chronic liver disease. Can J Public Health. 2000;91:168–70. doi:10.1007/BF03404264.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommended adult immunization schedule for ages 19 years or older, United States, 2020. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/adult.html, accessed April 21, 2020.

- National Health Service (NHS). NHS vaccinations and when to have them: extra vaccines for at-risk people. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/nhs-vaccinations-and-when-to-have-them/, accessed June 9, 2020.

- Verma R, Hepatitis KP. A vaccine should receive priority in National Immunization Schedule in India. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8:1132–34. doi:10.4161/hv.20475.

- Mukherjee PS, Vishnubhatla S, Amarapurkar DN, Das K, Sood A, Chawla YK, Eapen CE, Boddu P, Thomas V, Varshney S, et al. Etiology and mode of presentation of chronic liver diseases in India: a multi centric study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0187033. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187033.

- Choudhuri G, Chaudhari S, Pawar D, Roy DS. Etiological patterns, liver fibrosis stages and prescribing patterns of hepato-protective agents in Indian patients with chronic liver disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 2018;66:58–63.

- Joshi N, Rao S, Kumar A, Patil S, Hepatitis RS. A vaccination in chronic liver disease: is it really required in a tropical country like India? Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25:137–39. doi:10.4103/0255-0857.32720.

- Hussain Z, Das BC, Husain SA, Murthy NS, Kar P. Increasing trend of acute hepatitis A in north India: need for identification of high-risk population for vaccination. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:689–93. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04232.x.

- Ramachandran J, Eapen CE, Kang G, Abraham P, Hubert DD, Kurian G, Hephzibah J, Mukhopadhya A, Chandy GM. Hepatitis E superinfection produces severe decompensation in patients with chronic liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:134–38. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03188.x.

- Anand AC, Nagpal AK, Seth AK, Dhot PS. Should one vaccinate patients with chronic liver disease for hepatitis A virus in India? J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:785–87.

- Shalimar SV, Singh SP, Duseja A, Shukla A, Eapen CE, Kumar D, Pandey G, Venkataraman J, Puri P, Narayanswami K, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in India: the Indian national association for study of the liver consortium experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(10):1742–49. doi:10.1111/jgh.13340.

- Acharya SK, Batra Y, Saraya A, Hazari S, Dixit R, Kaur K, Bhatkal B, Ojha B, Panda SK. Vaccination for hepatitis A virus is not required for patients with chronic liver disease in India. Natl Med J India. 2002;15:267–68.

- Xavier S, Anish K. Is hepatitis A vaccination necessary in Indian patients with cirrhosis of liver? Indian J Gastroenterol. 2003;22:54–55.

- Radha Krishna Y, Saraswat VA, Das K, Himanshu G, Yachha SK, Aggarwal R, Choudhuri G. Clinical features and predictors of outcome in acute hepatitis A and hepatitis E virus hepatitis on cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2009;29:392–98. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01887.x.

- Shah AS, Amarapurkar DN. Natural history of cirrhosis of liver after first decompensation: a prospective study in India. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018;8:50–57. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2017.06.001.

- Kumar A, Gupta V, Arora A. Most liver related deaths in India are caused by alcohol: an audit of liver mortality from tertiary care center in North India [abstract]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:e37. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2016.09.092.

- Ray G. Trends of chronic liver disease in a tertiary care referral hospital in Eastern India. Indian J Public Health. 2014;58:186–94. doi:10.4103/0019-557X.138630.

- Majumdar A, Misra P, Sharma S, Kant S, Krishnan A, Pandav CS. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in an adult population in a rural community of Haryana, India. Indian J Public Health. 2016;60:26–33. doi:10.4103/0019-557X.177295.

- Duseja A, Najmy S, Sachdev S, Pal A, Sharma RR, Marwah N, Chawla Y. High prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among healthy male blood donors of urban India. JGH Open. 2019;3:133–39. doi:10.1002/jgh3.12117.

- Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet 2015; 386:1546–55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X.

- Goel A, Seguy N, Aggarwal R. Burden of hepatitis C virus infection in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:321–29. doi:10.1111/jgh.14466.

- Worldometer. India population. Available at https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/india-population/, accessed June 9, 2020.

- Sarin SK, Kumar M, Eslam M, George J, Al Mahtab M, Akbar SMF, Jia J, Tian Q, Aggarwal R, Muljono DH, et al. Liver diseases in the Asia-pacific region: a Lancet gastroenterology & hepatology commission. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:167–228. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30342-5.

- GBD. Cirrhosis collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2020(5):245–66. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30349-8.

- Bhattacharyya M, Barman NN, Goswami B. Survey of alcohol-related cirrhosis at a tertiary care center in North East India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2016;35:167–72. doi:10.1007/s12664-016-0651-2.

- Pati GK, Singh A, Misra B, Misra D, Das HS, Panda C, Singh SP. Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) in coastal Eastern India: “a single-center experience”. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2016;6:26–32. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2015.08.002.

- Kulkarni S, Sharma M, Rao PN, Gupta R, Reddy DN. Acute on chronic liver failure-in-hospital predictors of mortality in ICU. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018;8:144–55. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2017.11.008.

- Dhotial A, Kapoor D, Kumar N. Seroprevalence of hepatitis A virus antibody in patients with chronic liver disease - experience from a tertiary care hospital in north India. Trop Gastroenterol. 2002;23:170–71.

- Duseja A, Sharma S, Das K, Dhiman RK, Chawla YK. Is vaccination against hepatitis A virus required in patients with cirrhosis of the liver? Trop Gastroenterol. 2004;25:162–63.

- John A, Chatni S, Narayanan VA, Balakrishnan V, Nair P. Seroprevalence of hepatitis A virus in patients with chronic liver disease from Kerala: impact on vaccination policy. J Indian Med Assoc. 2009;107:859–61.

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Sánchez PJ, Faix RG, Poindexter BB, Van Meurs KP, Bizzarro MJ, Goldberg RN, Frantz ID 3rd, Hale EC, et al. Early onset neonatal sepsis: the burden of group B Streptococcal and E. coli disease continues. Pediatrics. 2011;127:817–26. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-2217.

- Khanna S, Vohra P, Jyoti R, Vij JC, Kumar A, Singal D, Tandon R. Changing epidemiology of acute hepatitis in a tertiary care hospital in Northern India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:101–02.

- Advisory Committee on Vaccines & Immunization Practices (ACVIP). IAP guidebook on immunization 2018-2019. Balasubramanian S, Shastri DD, Shah AK, Chatterjee P, Pemde HK, Shivananda S, Guduru VK. eds. New Delhi (India): Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd.; 2020.

- Agrawal A, Singh S, Kolhapure S, Hoet B, Arankalle V, Mitra M. Increasing burden of hepatitis A in adolescents and adults and the need for long-term protection: a review from the Indian subcontinent. Infect Dis Ther. 2019;8:483–97. doi:10.1007/s40121-019-00270-9.

- Lee HW, Chang DY, Moon HJ, Chang HY, Shin EC, Lee JS, Kim KA, Kim HJ. Clinical factors and viral load influencing severity of acute hepatitis A. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130728. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130728.

- Poddar U, Ravindranath A. Is time ripe for hepatitis A mass vaccination? Indian Pediatr. 2019;56:731–32. doi:10.1007/s13312-019-1630-3.

- Aggarwal R, Goel A. Hepatitis A: epidemiology in resource-poor countries. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2015;28:488–96. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000188.

- Arankalle VA, Chadha MS, Chitambar SD, Walimbe AM, Chobe LP, Gandhe SS. Changing epidemiology of hepatitis A and hepatitis E in urban and rural India (1982-98). J Viral Hepat. 2001;8:293–303. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2893.2001.00279.x.

- Das K, Jain A, Gupta S, Kapoor S, Gupta RK, Chakravorty A, Kar P. The changing epidemiological pattern of hepatitis A in an urban population of India: emergence of a trend similar to the European countries. Eur J Epidemiol. 2000;16:507–10. doi:10.1023/a:1007628021661.

- Gadgil PS, Fadnis RS, Joshi MS, Rao PS, Chitambar SD. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis A in voluntary blood donors from Pune, Western India (2002 and 2004-2005). Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136:406–09. doi:10.1017/S0950268807008643.

- Arankalle V, Tiraki D, Kulkarni R, Palkar S, Malshe N, Lalwani S, Mishra A. Age-stratified anti-HAV positivity in Pune, India after two decades: has voluntary vaccination impacted overall exposure to HAV? J Viral Hepat. 2019;26:757–60. doi:10.1111/jvh.13074.

- Arankalle VA, Tsarev SA, Chadha MS, Alling DW, Emerson SU, Banerjee K, Purcell RH. Age-specific prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis A and E viruses in Pune, India, 1982 and 1992. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:447–50. doi:10.1093/infdis/171.2.447.

- Deoshatwar AR, Gurav YK, Lole KS. Declining trends in Hepatitis A seroprevalence over the past two decades, 1998-2017, in Pune, Western India. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e121. doi:10.1017/S0950268820000953.

- Acharya SK, Batra Y, Bhatkal B, Ojha B, Kaur K, Hazari S, Saraya A, Panda SK. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis A virus infection among school children in Delhi and north Indian patients with chronic liver disease: implications for HAV vaccination. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:822–27. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03051.x.

- Kumar S, Ratho RK, Chawla YK, Chakraborti A. The incidence of sporadic viral hepatitis in North India: a preliminary study. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:596–99.

- Irshad M, Singh S, Joshi YK Viral hepatitis in India: a report from Delhi. Glob J Health Sci 2010; 2:96–103.

- Jain P, Prakash S, Gupta S, Singh KP, Shrivastava S, Singh DD, Singh J, Jain A. Prevalence of hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus and hepatitis E virus as causes of acute viral hepatitis in North India: a hospital based study. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2013;31:261–65. doi:10.4103/0255-0857.115631.

- Tewari R, Makeeja V, Dudeja M. Prevalence of hepatitis A in southern part of Delhi, India. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2016;5:2067–70. doi:10.5455/ijmsph.2016.20112015426.

- Sharma AK, Dutta U, Sinha SK, Kochhar R. Upsurge in vaccine preventable hepatitis A virus infection in adult patients from a tertiary care hospital of North India. Poster presentated at the 17th International Congress on Infectious Diseases. Int J Infect Dis. abstract 43.233]. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299473755_Upsurge_in_vaccine_preventable_hepatitis_A_virus_infection_in_adult_patients_from_a_tertiary_care_hospital_of_North_India, accessed. 2016;45S:457. April 23, 2020.

- Poddar U, Thapa BR, Prasad A, Singh K. Changing spectrum of sporadic acute viral hepatitis in Indian children. J Trop Pediatr. 2002;48:210–13. doi:10.1093/tropej/48.4.210.

- Mittal A, Bithu R, Vyas N, Maheshwari RK. Prevalence of hepatitis A virus and hepatitis E virus in the patients presenting with acute viral hepatitis at a tertiary care hospital Jaipur Rajasthan. N Niger J Clin Res. 2016;5:47–50. doi:10.4103/2250-9658.197436.

- National Health Portal (NHP) India. Universal immunisation programme. Available at https://www.nhp.gov.in/universal-immunisation-programme_pg, accessed June 5, 2020.

- National Centre for Disease Control. Viral hepatitis: the silent disease facts and treatment guidelines. Available at https://ncdc.gov.in/linkimages/guideline_hep20158117187417.pdf, accessed April 30, 2020.

- Expert Group of the Association of Physicians of India on Adult Immunization in India. Executive summary: the association of physicians of India evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on adult immunization. J Assoc Physicians India 2009;57:345–56.

- Indian Society of Nephrology. Indian Society of Nephrology guidelines for vaccination in chronic kidney disease. Indian J Nephrol. 2016;26(Suppl1):S1–S30.

- Indian Medical Association. Life course immunization guidebook. A quick reference guide. Available at http://www.ima-india.org/ima/pdfdata/IMA_LifeCourse_Immunization_Guide_2018_DEC21.pdf, accessed April 5, 2019.

- Sri Lanka Medical Association (SLMA). SLMA guidelines and information on vaccines. Available at https://slma.lk/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/GSK-SLMA-Guidelines-Information-on-Vaccines.pdf, accessed June 9, 2020.

- Chitambar SD, Chadha MS, Joshi MS, Arankalle VA. Prevalence of hepatitis A antibodies in western Indian population: changing pattern. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1999;30:273–76.

- Waghray A, Waghray N, Khallafi H, Menon KV. Vaccinating adult patients with cirrhosis: trends over a decade in the United States. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:5795712. doi:10.1155/2016/5795712.