ABSTRACT

In anticipation of a potential vaccine for COVID-19, vaccine uptake may be critical in overcoming the pandemic, especially in countries like the Philippines, which has among the highest rates of infection in the region. Looking at the progress of vaccination in the country – its promises, pitfalls, and challenges – may provide insight for public health professionals and the public. The history of vaccination in the Philippines is marked by strong achievements, such as the establishment and growth of a national programme for immunization, and importantly, the eradication of poliomyelitis and maternal and neonatal tetanus. It is also marred by critical challenges which provide a springboard for improvement across all sectors – vaccine stock-outs,

strong opposition from certain advocacy groups, and the widely publicized Dengvaxia controversy. Moving forward, with recent surveys having shown that vaccine confidence has begun to improve, these experiences may inform the approaches taken to address vaccine uptake. These lessons from the past highlight the importance of a strong partnership between health leaders and the local community, bearing in mind cultural appropriateness and humility; the engagement of multidisciplinary stakeholders; and the importance of foresight in preparing public health infrastructure for the arrival of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Introduction

Much hope for life after the COVID-19 pandemic lies in the potential success of vaccines. Multiple vaccines are in various stages of development,Citation1 and preliminary results from various trials are promising.Citation2–4 However, the success of a vaccine is incumbent upon uptake in the general population.Citation5

The Philippines has among the highest Covid-19 infection rates in the region, interlaced amidst economic and political ramifications.Citation6 In countries like the Philippines, population adherence to vaccines may be critical to overcoming the pandemic.Citation7 Adherence, however, is dependent on the population’s willingness to receive the vaccine.Citation8 Analysis of the history of vaccine uptake in the Philippines may highlight pitfalls and challenges that may impact efforts to disseminate a future Covid-19 vaccine. Importantly, an eye toward history may provide insight – and foresight – as public health authorities and healthcare professionals plan the steps forward.

Overview history of vaccination in the Philippines: promises and pitfalls

In 1976, the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) was established in the Philippines through Presidential Decree No. 996, with the assistance of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in order to combat the top infectious diseases causing child mortality through increased accessibility to preventive care. This programme made basic immunization compulsory for children under the age of 8, and covered six vaccine-preventable diseases at the time: tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and measles. A National Immunization Committee (NIC) was formed in 1986 to take charge of coordinating the EPI.Citation9 The EPI was revised and expanded in 2010 to cover mumps, rubella, Hepatitis B, and H. influenza type B, through Republic Act No. 10152 – the “Mandatory Infants and Children Health Immunization Act of 2011”. This covered responsibilities of health care workers (i.e., to educate pregnant mothers on the importance of vaccination) as well as continuing education programs for health care personnel. Importantly, the Act mandated basic immunization to be freely given at any government health facility to infants and children up to 5 years of age.Citation10

Recently, newer vaccines have been introduced, such as the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), rotavirus vaccine, and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Beginning in 2013, school-based immunization was the strategy of choice to target school-aged children for more age-appropriate vaccines and missed doses for basic vaccines, and was administered by the Department of Health (DOH) in coordination with the Department of Education (DepEd) and the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG). Vaccination of senior citizens with PCV and influenza vaccines was also mandated in the program through Republic Act No. 9994 – the “Expanded Senior Citizens Act of 2010”.Citation11

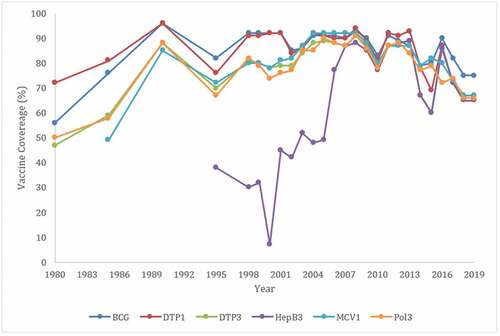

Despite having eradicated poliomyelitis in 2000, and having adopted various strategies to improve immunization coverage,Footnote1 vaccine coverage declined significantly from 2010 to 2015. shows the estimates of immunization coverage in the Philippines for BCG, DTP1, DTP3, HepB3, MCV1, and Pol3.Footnote2 In particular, DTP1 declined from a 98% coverage rate in 2013 to 69% in 2015, and further declined after a spike in 2016, completely missing the Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011–2020 (GVAP) goal of reaching 90% national coverage and 80% coverage in every district for DPT-containing vaccines.Citation12,Citation13 MCV coverage saw a steady decline in the aftermath of a measles outbreak in 2014; post-Dengvaxia®, MCV coverage declined even further, with another outbreak occurring in early 2019.Citation14 Because of this decline, many sites of resurgence of measles around the world have been traced back to the Philippines.Citation12,Citation15 Notably, three rubella outbreaks also occurred in the recent past – once in 2001, then in 2011, and finally in 2017.Citation14 Fluctuating coverage over the years was also reported in the Philippine National Demographic and Health Survey 2017 (NDHS), with the percentage of children aged 12 to 23 months who received all basic vaccinationsFootnote3 increasing from 72% in 1993 to 80% in 2008, and declining steadily after that from 77% in 2013 to 70% in 2017.Citation16

Figure 1. WHO-UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage. Philippines (PHL) 2019 revision. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/estimates?c=PHL.Citation12

Several key events may underlie the most significant dips in the graph above. In 1995, despite anti-tetanus vaccinations having been administered since 1983, a campaign was launched by pro-life groups and anti-abortion advocates to stop the administration of the tetanus toxoid vaccine. These groups alleged that the vaccine contained a small amount of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) in order to induce abortion or produce infertility; this claim may also have been augmented by reports of adverse events following immunization (AEFI), particularly inflammation at the injection site.Citation17,Citation18 Efforts to understand the public’s perception of vaccines, and catering educational information toward tackling potentially false claims about vaccine safety, may have contributed toward allaying fears regarding AEFI. Indeed, in spite of this challenge, maternal and neonatal tetanus was eliminated in the country in 2017 due to continued efforts to promote vaccine adherence. The significant and sharp decline in immunization coverage for DPT and Hepatitis B from 2014 to 2015, and continuing on to 2016, may be attributed to vaccine stock-outs.Citation19

In 2016, the Philippines incorporated the newly-licensed dengue vaccine (Dengvaxia®) into its national immunization programme, despite the mechanism of action being equivocal. It was rolled out in an expedited manner in response to an exceedingly high burden of disease in the country.Citation7,Citation20–22 The occurrence of adverse reactions in children that some have attributed to Dengvaxia®, along with inadequate social preparation and risk communication, inadvertently led to a widespread controversy amidst media hype and political discord. This media hype was possibly fueled even further by a divided stance and a diversity in opinion among the members of the medical community in the Philippines.Citation21

In the aftermath of this controversy, confidence in vaccines and/or the national immunization programme in the country plummeted.Citation21 Shortly thereafter, in early 2019, measles outbreaks were declared in several regions across the Philippines.Citation23 There were more than 33,000 cases, overrunning the capacity of many hospitals. A measles vaccination campaign was launched in response; however, challenges in administering the vaccine were met, such as the tendency for mothers to give false reports of their children’s vaccination status out of fear of being scolded by their physicians,Citation24 possibly suggesting a lack of confidence in vaccination. This may bias the next NDHS report disproportionately given an already-existing recall bias, as information on vaccination coverage is obtained not only from written vaccination records, but also from verbal reports, the latter especially in cases where official documents would not be available.Citation16

The response to vaccines other than DENV in light of public fears about DENV sheds light on the value of learning from the past. Understanding the public response – and its magnitude – to unforeseen AEFI should inform the care with which vaccination programs are implemented in the future. The Dengvaxia experience highlights the need to engage multidisciplinary stakeholders in the approach to increasing vaccine adherence. Importantly, cooperation among healthcare experts, media, and policymakers may have improved the communication between the vaccine’s manufacturer and providers on the ground and may have mitigated the backlash against vaccines in general, in light of adverse effects potentially associated with DENV.

Notably, a PulseAsia survey conducted in the Philippines in December 2018 reported that 78% of respondents believed that vaccines are safe for themselves, their children, or their family members.Citation25 These findings suggest the positive effects of education campaigns and widespread confidence in the safety of vaccines, despite the DENV controversy. It is possible, therefore, that education efforts moving forward should focus on demonstrating the utility of vaccines for a population that deems vaccines safe. These successes should also inform the approaches taken to optimize public reception of a potential COVID-19 vaccine.

Lessons and considerations for Covid-19

The successes and shortcomings highlighted in the recent history of vaccination in the Philippines shed light on lessons that can inform measures to improve vaccine uptake if and when a successful vaccine for COVID-19 becomes available. The past has shown the importance of a partnership between health leaders and the local community; the engagement of multidisciplinary stakeholders; and the importance of foresight in preparing vaccine infrastructure.

Firstly, cultural humility and appropriateness are important in promoting vaccine uptake, especially when there is a large gap in knowledge between the healthcare provider and the recipient of care, particularly for novel therapies (such as DENV when it was newly released). There may be a knowledge monopoly biased toward the physician, where patients tend to place their trust in the former to make decisions. Community engagement and education are therefore important in ensuring individuals make informed decisions about their healthcare.Citation7

Efforts to engage barangay and other local leaders may prove critical in engendering trust in the population.Citation7 Much in the same way that providers are encouraged to engage in a patient-provider partnership to grant autonomy to patients while simultaneously encouraging treatment adherence, it is critical to engage in a partnership with local leaders to create trust and encourage vaccine adherence. For example, those implementing programs may engage barangay tanods (local community custodians) and trusted community individuals and leaders; community health workers could be trained and equipped to administer the vaccine and contextualize medical jargon into the vernacular; and finally, for health care practitioners to speak eye-to-eye and lessen the knowledge gap when asking individuals to vaccinate.

Secondly, multidisciplinary collaboration is necessary. Previous crises such as the Dengvaxia controversy and now the eruption of the pandemic in the country have pulled the medical and academic community apart, when it is necessary for us to be united most. Efforts to align and build coalition among healthcare providers, data scientists, policymakers, private sector and media are merited. Healthcare workers may provide insight into attitudes toward the vaccine and the pandemic at the patient level; PulseAsia reported healthcare workers as the second-largest influence on individuals’ decision-making for vaccination next to the Department of Health, with family as the third most influential force.Citation25 Data scientists may help define patterns of success and failure among various interventions.Citation26 Policymakers, particularly at the local level, may influence local actions and decisions among citizens in their jurisdictions.Citation5,Citation27 The private sector – mavericks in supply chain and logistics management – may understand the macroscopic supply and demand factors at play, and could aid policymakers in program implementation. Both traditional and social media may inform what patients learn about vaccines. The ability to shape the narrative and public opinion makes the media a critical player in risk communication and community engagement.Citation28–30 Although the Philippines has some of the highest rates of social media use, traditional media is a key channel in advocating for vaccine adherence; several recent surveys during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that Filipinos’ primary source of information continues to be traditional media (i.e., television and/or radio), followed by social media.Citation30–32 Multidisciplinary cooperation well in advance of a future vaccine may help prime the population for adequate vaccine uptake.

Lastly, there is no shortcut to building a reliable vaccine infrastructure, especially for the 23rd most densely populated country in the world. Whether the Philippines would decide to manufacture its own vaccines or participate in advanced market commitments, one thing remains clear: the infrastructure for vaccine delivery needs to be built fast, and in a manner that is sustainable, as this would be the highway for future vaccines. Medical infrastructure is not something that will be built from scratch; years of investment in the expanded programme on immunization exist as its foundation, but its completion needs to be accelerated. Efforts must be made to modernize supply chains, taking into account the challenging archipelagic geography as well as multiple geographically isolated and disadvantaged areas (GIDAs). For example, routes for cold chains should be planned and prepared beforehand, in anticipation of an eventual vaccine. The Build! Build! Build! (BBB) Program of the national government promises to connect far flung areas through new roads, expressways, bridges, and railways, among others.Citation33 Continuous innovation is necessary to supplement these developments, which may include the development of sea ambulances, in order to make GIDAs more accessible.

Furthermore, we must engage all members of the community in a way that fosters trust. In addition to simply training health workers to educate their communities, ensuring that enough health workers are present and that all are adequately compensated and protected while in the line of duty would prepare the human infrastructure as a substrate ready to accept a COVID-19 vaccine when one becomes available. Training health workers to vaccinate is as important as training them for risk communication and managing refusals. Lastly, improving vaccine and science literacy among all members of the community is a key step in building a patient infrastructure equipped to make informed decisions in immunization.

These lessons have in common the need for foresight, so we are not caught blindsided when the vaccine arrives. In gaining a better understanding of the pitfalls and promises of the history of vaccination in the Philippines, lessons from the past must be used to guide the future.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The Department of Health of the Philippines had adopted a “Reaching Every Barangay” strategy from the “Reaching Every District” strategy of the WHO-UNICEF in 2004, which included data analysis, outreach services, and strengthening links between the community and service providers.

2. BCG – % infants who received one dose of the Bacillus Calmette Guerin vaccine at birth; DTP1/DTP3 – % infants who received the 3rd dose of either oral or inactivated polio-containing vaccine; HepB3 – % infants who received the 3rd dose of Hepatitis B-containing vaccine following the birth dose; MCV1 – % infants who received the 1st dose of measles-containing vaccine; Pol3.

3. Basic vaccinations include one dose of BCG vaccine, three doses of DPT-containing vaccine, three doses of polio vaccine (IPV or OPV), and one dose of measles-containing vaccine (measles or MMR).

References

- Willis VC, Arriaga Y, Weeraratne D, Reyes F, Jackson GP. A narrative review of emerging therapeutics for COVID-19. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2020. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.07.004.

- Xia S, Duan K, Zhang Y, Zhao D, Zhang H, Xie Z, Li X, Peng C, Zhang Y, Zhang W, et al. Effect of an inactivated vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 on safety and immunogenicity outcomes: interim analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.15543.

- Corbett KS, Edwards D, Leist SR, Abiona OM, Boyoglu-Barnum S, Gillespie RA, Himansu S, Schafer A, Ziwawo CT, DiPiazza AT, et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine development enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. bioRxiv Prepr Serv Biol. 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.06.11.145920.

- Kandimalla R, John A, Abburi C, Vallamkondu J, Reddy PH. Current status of multiple drug molecules, and vaccines: an update in SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics. Mol Neurobiol. 2020;57(10):4106–16. doi:10.1007/s12035-020-02022-0.

- Malik AA, McFadden SM, Elharake J, Omer SB. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. medRxiv. 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.05.22.20110700.

- Salva EP, Villarama JB, Lopez EB, Sayo AR, Villanueva AMG, Edwards T, Han SM, Suzuki S, Seposo X, Ariyoshi K, & Smith C. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with suspected COVID-19 admitted in Metro Manila, Philippines. Trop Med Health. 2020. doi:10.1186/s41182-020-00241-8.

- Reyes MSGL, Lee KMG, Pedron AML, Pimentel JMT, Pinlac PAV. Factors associated with the willingness of primary caregivers to avail of a dengue vaccine for their 9 to 14-year-olds in an urban community in the Philippines. Vaccine. 2020;38(1):54–62. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.001.

- Harrison EA, Wu JW. Vaccine confidence in the time of COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(4):325–30. doi:10.1007/s10654-020-00634-3.

- World Health Organization - Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Meeting of National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups for Asean Countries; 2019, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. [accessed 2020 Aug 29] https://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/14535/RS-2019-GE-49-MYS-eng.pdf.

- Government of the Philippines. Republic Act No. 10152 | official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Published 2011 [accessed 2020 Aug 29]. http://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2011/06/21/republic-act-no-10152/.

- Government of the Philippines. Republic Act No. 9994 - expanded senior citizens’ act of 2010. [accessed 2020 Aug 30]. http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/research/Philippines/RA9994-TheExpandedSeniorCitizensAct.pdf.

- World Health Organization. WHO UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage for Philippines (PHL). WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system. Global summary; Published 2020 [accessed 2020 Aug 29]. https://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/estimates?c=PHL.

- World Health Organization. WHO | global vaccine action plan 2011–2020. 2013 [accessed 2020 Aug 30]. https://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_doc_2011_2020/en/%0Ahttps://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_doc_2011_2020/en/%0Ahttp://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_doc_2011_2020/en/.

- World Health Organization. Incidence time series for Philippines (PHL). WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system. Global summary; Published 2020 [accessed 2020 Aug 30]. https://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/incidences?c=PHL.

- World Health Organization - Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Eighth Annual Meeting of the Regional Verification Commission for Measles and Rubella Elimination in the Western Pacific. 2019 [accessed 2020 Aug 29]. http://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/13936/RS-2017-GE-49-CHN-eng.pdf.

- Philippine Statistics Authority. Philippines national demographic and health survey 2017. 2018 [accessed 2020 Aug 30]. www.DHSprogram.com.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, Nickels E, Jeram S, Schuster M. Mapping vaccine hesitancy-Country-specific characteristics of a global phenomenon. Vaccine. 2014;32(49):6649–54. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.039.

- Tiff over anti-tetanus vaccine now erupted into battle. International/Philippines - PubMed. Vaccine Wkly. 1995;(Jul 24):11–13. [Accessed Aug 30, 2020]. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12289950/.

- World Health Organization, UNICEF. Progress and challenges with achieving universal immunization coverage: 2015 estimates of immunization coverage WHO/UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage (Data as of July 2016). 2016.

- Migrino JJ, Gayados B, Birol RJ, De Jesus L, Lopez CW, Mercado WC, Tolosa JM, Torreda J, Tulugan G. Factors affecting vaccine hesitancy among families with children 2 years old and younger in two urban communities in Manila, Philippines. West Pac Surveill Response J. 2020. doi:10.5365/wpsar.2019.10.2.006.

- Larson HJ, Hartigan-Go K, de Figueiredo A. Vaccine confidence plummets in the Philippines following dengue vaccine scare: why it matters to pandemic preparedness. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(3):625–27. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1522468.

- Hou J, Shrivastava S, Loo HL, Wong LH, Ooi EE, Chen J. Sequential immunization induces strong and broad immunity against all four dengue virus serotypes. Npj Vaccines. 2020;5(1):1–11. doi:10.1038/s41541-020-00216-0.

- Department of Health - Philippines. DOH EXPANDS MEASLES OUTBREAK DECLARATION TO OTHER REGIONS | department of Health website. Published 2019 [accessed 2020 Sept 11]. https://www.doh.gov.ph/node/16647.

- Beaubien J. How The Philippines Is Fighting One Of The World’s Worst Measles Outbreaks: NPR. NPR; Published 2019 [accessed 2020 Aug 29]. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2019/05/23/725726094/the-philippines-is-fighting-one-of-the-worlds-worst-measles-outbreaks.

- PulseAsia Research Inc. Ulat Ng Bayan Survey: preliminary Tables on DOH Immunization Programs. 2018.

- Dee EC, Paguio JA, Yao JS, Stupple A, Celi LA. Data science to analyse the largest natural experiment of our time. BMJ Heal Care Informatics. 2020:e100177. doi:10.1136/bmjhci-2020-100177.

- Auger KA, Shah SS, Richardson T, Hartley D, Hall M, Warniment A, Timmons K, Bosse D, Ferris SA, Brady PW, et al. Association between statewide school closure and COVID-19 incidence and mortality in the US. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.14348.

- Paguio JA, Yao JS, Dee EC. Silver lining of COVID-19: heightened global interest in pneumococcal and influenza vaccines, an infodemiology study. Vaccine. 2020. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.06.069.

- David CC, San Pascual RS, Torres ES. Reliance on Facebook for news and its influence on political engagement. PLoS One. 2019. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212263.

- Lau LL, Hung N, Go DJ, Ferma J, Choi M, Dodd W, Wei X. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of COVID-19 among income-poor households in the Philippines: A cross-sectional study. J Glob Health. 2020. doi:10.7189/JOGH.10.011007.

- Social Weather Station. Preferred Touchpoints for UHC. Unpublished raw data. 2019.

- Philippine Survey and Research Center. Vaccine Confidence Survey. Unpublished raw data. 2019.

- Republic of the Philippines - Subic-Clark Alliance for Development. Build build build projects | subic-clark alliance for development | world within reach. [ accessed 2020 Sep 19]. https://scad.gov.ph/build-build-build/.