?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Vaccines not only protect individuals, but also prevent the spread of vaccine-preventable diseases in the community. Vaccine rejection in Turkey increased 125-fold between 2012 and 2019. Thus, this cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the level of knowledge of family physicians about vaccination, which can be the keystone of vaccine rejection. Evaluations were also made of vaccine recommendations, practice, and confidence in vaccine safety. The study was conducted using a 41-item questionnaire, completed by 804 (3.3%) family physicians serving in Turkey. The most common reasons for vaccine rejection were found to be fear of disease from the vaccine substance at the rate of 53.7% (n = 298), religious reasons at 32.3% (n = 179), disbelief of protection at 9.9% (n = 55), and fear of infertility at 4.1% (n = 23). Logistic regression analysis was applied to determine the factors affecting the power of the family physician’s recommendation. The results showed that age >41 years (OR = 1.625 (1.129–2.34)), having self-efficacy (OR = 1.628 (1.183–2.24)) and belief in the usefulness of the vaccine made a positive contribution to the power to recommend vaccines (OR = 1.420 (1.996–1.012)). The results of this study demonstrated that training on vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases has a positive effect on self-efficacy (p < .0001). This study can be considered of value as the first to demonstrate the beliefs and attitudes of family physicians in Turkey. Further training courses to increase knowledge of vaccines, vaccine-preventable diseases, and communication skills would be of benefit for family physicians.

Introduction

Vaccination practice is one of the major tools in protecting the public from infectious diseases.Citation1 Countries apply vaccination programs for local epidemiological diseases and pandemic diseases in childhood and adult age groups.Citation2 Vaccines not only protect individuals, but also prevent the spread of vaccine-preventable diseases in the community. However, there is controversy over the direct and indirect harm of vaccines to human health.Citation3,Citation4 The greater attention paid to concerns about diseases caused by vaccines rather than the success of vaccines has given rise to the anti-vaxxer lobby.Citation5 Some studies have indicated that substances in vaccines can cause long-term complications. There are studies reporting multiple sclerosis cases following the Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine or increased incidence of Guillain-Barre syndrome, and autism cases following the MMR vaccine.Citation6–9 Health-care professionals making similar public statements in the media and social media can be seen in every country. Consequently, publications that question the safety of vaccines without scientific evidence has led to increased parental concerns and rejection of vaccines.Citation10,Citation11 Despite any concerns over vaccine safety or religious reasons, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that vaccines are more effective and safer than therapeutic drugs.Citation12

Turkey is a Muslim country in a strategic position between the Middle East and Europe and has a young population. To address potential risks of vaccine-preventable infectious diseases, the Expanded Program on Immunization, launched by the WHO, is being conducted in Turkey. Vaccines are delivered not only to children, but also to health workers, people aged over 65, and risk groups, and expenses are paid by the Ministry of Health.Citation13,Citation14 However, acceptance of vaccine is decreasing in Turkey: In 2011, vaccines were rejected by 183 families in Turkey, and over the following 7 years, this number increased 125-fold to reach 23,000.Citation15 In Turkey, vaccine practice is implemented by family physicians in primary health-care centers under the control of the Ministry of Health and higher vaccination rates have been reached compared to some other countries. In most countries, family physicians are the keystone of vaccine practice and have a great influence on the attitudes and knowledge of parents.Citation10,Citation16,Citation17 For that reason, it is of particular importance that the family physician trust vaccines, has good knowledge of the benefits and efficacy of vaccines and can recommend vaccines following established guidelines. It has been reported that physicians’ self-efficacy contributes to vaccine safety and benefits.Citation18 However, some publications have reported that the good relationship of the family physician with parents has little or no effect on parents’ attitudes to vaccine rejection.Citation19,Citation20 The conceptional gap in the case of vaccine rejection improves approaches that are practically applicable and empowered with evidence. To solve this problem, the continued collaboration of family physicians with parents is crucial.Citation15

There are known to be various conflicting attitudes among family physicians about vaccine rejection.Citation17 A better understanding of the concept of vaccines by both doctors and individuals, by emphasizing the preventive medicine side rather than the industrial side and informing the public about vaccine safety with well-designed studies can prevent vaccine rejection.Citation19,Citation20 Although vaccine rejection is evaluated as an individual right, controversy remains about whether parents can exercise such a right over their children and the public health risk of infectious diseases.Citation21

Given their significance as the first point of consultation in health issues for target groups for the vaccine, there is a need to examine the opinions and attitudes of family physicians toward vaccines. For this reason, this study aims at assessing family physicians’ strength in terms of recommending the vaccine, their beliefs in vaccination safety and usefulness, and their self-efficacy perceptions toward vaccinating.

Materials and methods

A questionnaire was used in this cross-sectional study to measure the level of knowledge of vaccines of family physicians working in all regions of Turkey, the awareness of the usefulness of vaccines, vaccine safety, and vaccine rejection, and the recommendations made. In Turkey, ‘family practice’ was initiated as a pilot scheme in 2004 and became fully operational in all the regions in 2013.Citation22 The current number of family physicians is 24,000, serving almost 100% of the 80 million population.

Determination of sample

The following formula was used to represent the target population and calculate the minimum sample size.

Where:

z = Z value (e.g., 1.96 for 95%confidence level)

p = percentage of picking a selection (prevalence) expressed as a decimal

e = margin of error expressed as a decimal

N = total number of family physicians in Turkey, which is approximately 24,000 in 2020.

Since there were no previously conducted studies on this subject, to reach the maximum number of samples, the p value was considered as 0.5, which is the assumption of 50% for this study. At a 95% confidence level and a 3% margin of error, the minimum sample size was calculated as 1022.

Turkey is geographically divided into seven regions. Marmara region has the largest population and number of family physicians among these regions, whereas the Southeast Anatolian region has the lowest population and number of family physicians. For the generalizability of the study, the calculated sample was stratified according to the regional distributions of family physicians working in Turkey, i.e., more family physicians were recruited from the regions with a higher population.

Data collection

Data were collected between 07/03/2019 and 08/03/2019 with responses to online survey questions. For the survey, various web links on WhatsApp, Facebook, and Gmail were constructed and sent to the family physicians. The delivery of these links was made out of working hours for family physicians working in family health centers so as not to affect each other and maintain objectivity. The distribution of the links to the provinces followed a certain sequence. Physicians who were members of the Federation of Family Medicine were contacted, when a single person in each province was monitored on the Internet during that time. For various reasons, 218 Family Physicians who were sent questionnaires refused to participate in the study. In total, 78.6% (804) of the targeted sample was reached. The security of the data was assigned to SurveyMonkey enterprise.

Variables and measurement tools

After consideration of similar studies in the literature, a 41-item questionnaire was createdCitation17,Citation18,Citation23 While the questions for the 5-point Likert-scale were adopted from the literature,Citation17 the other questions were generated with respect to the peculiarities of the Turkish context. The survey is accessible as supplementary material. The survey contains asking for socio-demographic information, age groups in patients, recommendation practices, beliefs toward vaccinate safety, knowledge of vaccinate, evaluation of vaccinate usefulness, self-efficacy perceptions of own skills of vaccinating, own vaccination history, training, and rejection.

The responses to the questionnaire given as 5-point Likert-type responses were scored as follows: Physicians with a score of >15 from the five questions examining the power to recommend vaccination were identified as physicians who could demonstrate vaccination suggestion power accepting the answer option “undecided” with a score of three as the threshold. Similarly, the concerns of family physicians about vaccination safety were evaluated as positive <18 points. In the questions examining the belief in the benefit of vaccination, ≤4 points were evaluated as positive. In the questions examining the self-efficacy of family physicians, a score >9 was evaluated as positive.

Statistical analysis

Data obtained in the study were analyzed statistically using SPSS version 20.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive data were summarized as number (n) and percentage (%). Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to measure the significance between the sources affecting self-efficacy and training within the last year. Logistic regression analysis was applied to evaluate the factors affecting the vaccine recommendation power. The reliability of the questionnaire was tested and the Cronbach’s alpha value was determined as 0.64.

Participation in the study was voluntary. Approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam University Faculty of Medicine (decision no: 221).

Results

A total of 804 doctors from across Turkey were included in the study (78.6% calculated sample). The distribution of the participants according to regions was as follows: 26. 2% (211) participants lived in the Marmara region, 23.5% (189) in Southeast Anatolia, 21.5% (173) in the Mediterranean Region, 9.8% (79) in Inner Anatolia, 7.6% (61) in Easter Anatolia, 6.3% (51) in the Aegean Region, and 5.0% (40) in the Black Sea Region. 87.3% (n = 702) of the participants were working in a city and 12.7% (n = 102) in rural areas. Considering the distribution of the participants by region, the highest participation rate was achieved with 26.2% (n = 211) in the Marmara region, where the population of the country is the most dense. The participants comprised 505 (62.8%) males and 299 (37.2%) females with a mean age of 38.4 ± 9 years. In Turkey, routine vaccinations are applied to individuals aged ≤16 years and ≥65 years. According to the responses received 119 (14.8%) of the family physicians had a proportion of 0%–16% of the patients belonging to the age group ≤16, 268 (33.9%) a proportion of 17%–21%, 228 (28.8%) a proportion of 22%–25%, 176 (22.3%) a proportion of 26%–50%. For the age group ≥65, the proportions are as follows: 294 (37.0%) had a proportion of 0%–8%; 241 (30.4%) a proportion of 9%–12%; 127 (16.0%) a proportion of 13%–17%; 132 (16.6%) a proportion of 18% and more.

It was reported by 69% (n = 555) of the physicians that vaccines had been refused by at least one patient and 87% (n = 483) identified the rejected vaccines. The most rejected vaccines were the pentavalent vaccine (Diphtheria-Pertussis-Tetanus-Inactivated Polio-Hemophilus influenza type B-combined vaccine) at the rate of 34.0% (n = 164) followed by the Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR) combined vaccine at the rate of 22.4% (n = 108) ().

Table 1. Distribution of rejected vaccines

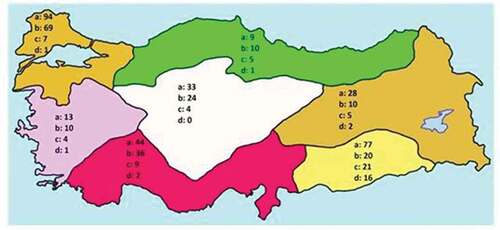

The most common reasons for rejection of the vaccine were fear of disease that could develop due to the vaccine substance in 53.7% (n = 298), religious reasons in 32.3% (n = 179), disbelief of its protection in 9.9% (n = 55), and fear of infertility in 4.1% (n = 23). When analyzed according to the geographical regions of Turkey, the highest rejection rate because of possible diseases was seen in all regions except the Black Sea region, where the highest rate was for religious reasons. Of the rejections because of fear of infertility, 69.6% (n = 16) were clustered in the Southeastern Anatolia region, 8.7% (n = 2) in the Mediterranean, 8.7% (n = 2) in the neighboring regions and 0.6% in the Marmara region. There were no cases of rejection due to infertility concerns in Central Anatolia ().

Figure 1. Distribution of causes of vaccine rejection by region

As 19 participants did not fully respond to the items related to vaccine suggestion power, safety, usefulness, and self-efficacy, these respondents were excluded. A score of >15 from the items questioning the power of vaccination suggestion was obtained by 61.2% (n = 481). A score of ≤4 points from items related to the benefits of the vaccine were obtained by 95.5% (n = 744). A score of <18 points from items related to the belief in vaccine safety were obtained by 87.3% (n = 680) and a score of >9 points related to confidence in the self-efficacy of their knowledge was obtained by 69.8% (n = 544) ().

Table 2. Attitudes of family physician about vaccine suggestions

Table 3. Attitudes of family physicions vaccine confidential/safety

Table 4. Opinions of family physicians about vaccine usefulness and self-efficacy

When the factors affecting the family physician’s suggestion power were evaluated with multivariate logistic regression analysis, age >41 years (OR = 1.625 (1.129–2.34)), having self-efficacy (OR = 1.628 (1.183–2.24)) and belief of vaccine usefulness were determined to make a positive contribution to the power of recommendation of vaccines (OR = 1.420 (1.996–1.012)) ().

Table 5. Variants that affects power of vaccine suggestions with logistic regression model

61.0% (n = 479) of the participants had a seasonal influenza vaccine in the last year and 84.8% (n = 666) of these showed their belief in preventive medicine according to their lipid profile. 60.0% (n = 471) of the family physicians received training on vaccines in the last year and 55.6% (n = 437) received training on vaccine-preventable diseases. The training about vaccine and vaccine-preventable diseases were found to contribute significantly to self-efficacy (p < .0001). 90.7% (n = 725) of the respondents reported that they trusted the information sources of family physicians and speeches of specialist colleagues about vaccination (the highest confidence in public), and 85.5% (n = 683) trusted Ministry of Health publications. 9.9% (n = 57) of the family physicians trusted colleagues who appeared in the media but did not have any expertise in this field.

Discussion

The most common cause of rejection reported by families in the current study was the possibility of adverse effects caused by the substances in the vaccines. Although religion is considered to have an important impact on society, religious reasons were the most common cause in only one region (Black Sea Region) and they were not the leading reason for vaccine rejection throughout the country. While concerns about Halal content in Muslim communities in different countries are the most important reason for vaccine rejection, this was not seen to be the case in the current study.Citation24,Citation25 The secular governance structure and modern education system for nearly a century in Turkey could have led to differences in behavior from other Muslim communities. Another reason for vaccine rejection is the concern that vaccines may cause infertility problems. In the current study, it was surprising that almost all the families with these concerns were living in the region with the highest birth rate.

The most frequently rejected vaccines in this study were pentavalent-combined vaccines followed by the MMR vaccine. International publications have reported that influenza vaccines, human papillomavirus, and newly emerging vaccines are rejected.Citation25 In the Ministry of Health routine vaccination program in Turkey, the hepatitis B vaccine is administered just afterbirth, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis and pentavalent-combined vaccine in the second month. That the parents’ decision to refuse vaccination was taken within 2 months after the birth shows that they do not have the stability of this decision before delivery. The fact that publications presenting evidence of a relationship between MMR vaccine and autism have been discussed for many years and more recent spread by media and social media tools may have led to this being the second most frequent rejection.Citation9,Citation26

The beliefs of the respondents in vaccine usefulness and safety were at a higher rate than reported in the study by VergerCitation17 et al. and lower than in studies by BonvilleCitation18 et al. in the USA. In the current study, belief in the usefulness of vaccination was seen to have a positive effect on the power of vaccine suggestion, and physician age of over 41 years was also determined to be important. Participants over a certain age have internalized the usefulness of vaccination by seeing the destruction of individuals who are not vaccinated in their social surroundings. Similarly, in an article by Wakefield about vaccine safety, it was reported that this age group has received training on vaccines on a topic that is strictly closed for discussion.

The results of this study showed that training on vaccines and preventable diseases has a positive effect on self-efficacy. As the respondents adopted the publications of the Ministry of Health as a reliable source of information rather than publications published abroad, it would be more appropriate for the Ministry of Health to provide training.Citation17,Citation27 Since the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, preventive medicine policies have been established independently of the government and the horizontal organizational model adopted with the confidence of health-care practitioners may explain the trust in the Ministry of Health. Family physicians have little confidence in colleagues who are willing to appear in the media but do not have any expertise in vaccination. According to the family physicians, there is a need for well-designed studies to identify and resolve the negative impacts on families, which have been created by colleagues with low academic reliability.

This study had some limitations, primarily that the sample size was not completely reached. The main reason for not reaching the targeted sample size was that the potential unwillingness for participation was not taken into account beforehand. Another limitation was that the respondents were asked to report only the most rejected vaccine, so the exact distribution of all rejected vaccines was not known.

Strength of the study is that that the proportion of family physicians in the different geographical regions of Turkey was taken into account, as it was explained in the methodology. Thus, the finding of our study can be extrapolated to all family physicians in Turkey.

Conclusions

The results of this study have demonstrated the power of vaccine recommendation of family physicians, which can be considered the cornerstone of vaccine immunization studies, the factors influencing this, and their beliefs in vaccine safety and usefulness. Acknowledging the significance of these factors, the data also suggest that an increase in rejection of vaccines is likely to continue. An important result is that beliefs about the effects of ingredients in vaccines are the most frequently shown reason. For that reason, it is important to provide family physicians with training instructing them about substances used in vaccines in order to increase the family physicians’ competencies in explaining vaccinates to patients. There is a need for further studies to examine the role of family physicians in solving this problem, to determine the attitudes of the families, and the factors affecting this increase.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (42.5 KB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website

References

- Andre FE, Booy R, Bock HL, Clemens J, Datta SK, John TJ, Lee BW, Lolekha S, Peltola H, Ruff TA, et al. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86(2):140–46. doi:10.2471/BLT.07.040089.

- Plotkin SL, Plotkin SA. A short history of vaccination. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA editors. Vaccines. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004. p. 1–15.

- Zipprich J, Winter K, Hacker J, Xia D, Watt J, Harriman K. Measles outbreak—California, December 2014–February 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:153–54.

- Woudenberg T, van Binnendijk RS, Sanders EA, Wallinga J, de Melker HE, Ruijs WL, Hahné SJ. Large measles epidemic in the Netherlands, May 2013 to March 2014: changing epidemiology. Euro Surveill. 2017 Jan 19;22(3):30443. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.3.30443.

- Global advisory committee on vaccine safety, 3–4 December 2003. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2004 Jan 16;79(3):16‐20.

- Sutton I, Lahoria R, Tan I, Clouston P, Barnett M. CNS demyelination and quadrivalent HPV vaccination. Mult Scler. 2009;15(1):116‐119. doi:10.1177/1352458508096868.

- Souayah N, Michas-Martin PA, Nasar A, Krivitskaya N, Yacoub HA, Khan H, Qureshi AI. Guillain-Barré syndrome after Gardasil vaccination: data from vaccine adverse event reporting system 2006–2009. Vaccine. 2011;29(5):886‐889. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.020.

- Ojha RP, Jackson BE, Tota JE, Offutt-Powell TN, Singh KP, Bae S. Guillain-Barre syndrome following quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination among vaccine-eligible individuals in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(1):232‐237. doi:10.4161/hv.26292.

- Wakefield AJ. MMR vaccination and autism. Lancet. 1999;354(9182):949‐950. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)75696-8.

- Gust DA, Strine TW, Maurice E, Smith P, Yusuf H, Wilkinson M, Battaglia M, Wright R, Schwartz B. Underimmunization among children: effects of vaccine safety concerns on immunization status. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):e16‐e22. doi:10.1542/peds.114.1.e16.

- Freed GL, Clark SJ, Butchart AT, Singer DC, Davis MM. Parental vaccine safety concerns in 2009. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):654‐659. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1962.

- Folb PI, Bernatowska E, Chen R, Clemens J, Dodoo ANO, Ellenberg SS, Farrington CP, John TJ, Lambert P-H, MacDonald NE, et al. A global perspective on vaccine safety and public health: the Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(11):1926–31. doi:10.2105/ajph.94.11.1926.

- Ministry of Health Republic of Turkey. [ accessed 2020 Aug 30]. https://hsgm.saglik.gov.tr/tr/asidb-anasayfa.

- Ministry of Health Republic of Turkey, Genişletilmiş Bağışıklama Programı Genelgesi. [ accessed 2020 Aug 30]. https://www.saglik.gov.tr/TR,11137/genisletilmis-bagisiklama-programi-genelgesi-2009.html

- Gür E. Vaccine hesitancy - vaccine refusal. Turk Pediatri Ars. 2019;54(1):1–2. Published 2019 Mar 1. doi:10.14744/TurkPediatriArs.2019.79990.

- Brown KF, Kroll JS, Hudson MJ, Ramsay M, Green J, Long SJ, Vincent CA, Fraser G, Sevdalis N. Factors underlying parental decisions about combination childhood vaccinations including MMR: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2010;28(26):4235‐4248. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.052.

- Verger P, Fressard L, Collange F, Gautier A, Jestin C, Launay O, Raude J, Pulcini C, Peretti-Watel P. Vaccine hesitancy among general practitioners and its determinants during controversies: a national cross-sectional survey in France. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(8):891–97. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.06.018.

- Bonville CA, Domachowske JB, Cibula DA, Suryadevara M. Immunization attitudes and practices among family medicine providers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(11):2646‐2653. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1371380.

- Henrikson NB, Opel DJ, Grothaus L, Nelson J, Scrol A, Dunn J, Faubion T, Roberts M, Marcuse EK, Grossman DC. Physician communication training and parental vaccine hesitancy: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):70‐79. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-3199.

- Sadaf A, Richards JL, Glanz J, Salmon DA, Omer SB. A systematic review of interventions for reducing parental vaccine refusal and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2013;31(40):4293‐4304. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.013.

- Leask J, Kinnersley P. Physician communication with vaccine-hesitant parents: the Start, not the end, of the story. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):180‐180. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-1382.

- Aile Hekimliği Kanunu. [ accessed 2020 Mar 2]. https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=17051&MevzuatTur=7&MevzuatTertip=5.

- Pulcini C, Massin S, Launay O, Verger P. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of general practitioners towards measles and MMR vaccination in southeastern France in 2012. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(1):38‐43. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12194.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, Nickels E, Jeram S, Schuster M. Mapping vaccine hesitancy–country-specific characteristics of a global phenomenon. Vaccine. 2014;32(49):6649‐6654. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.039.

- Wong LP, Sam IC. Factors influencing the uptake of 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine in a multiethnic Asian population. Vaccine. 2010;28(28):4499‐4505. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.043.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, Ouakki M, Bettinger JA, Guay M, Halperin S, Wilson K, Graham J, Witteman HO, MacDonald S, et al. Understanding vaccine hesitancy in Canada: results of a consultation study by the Canadian immunization research network. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156118. Published 2016 Jun 3. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156118.

- Yaqub O, Castle-Clarke S, Sevdalis N, Chataway J. Attitudes to vaccination: a critical review. Soc Sci Med. 2014;112:1‐11. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.018.