ABSTRACT

In Japan, the government’s recommendation for the HPV vaccine has been suspended for almost 8 years. A questionnaire survey was conducted in the Tsubaki Women’s Clinic, Matsuyama, Japan, to examine responses of the mothers of girls eligible for HPV vaccine before and after their doctor provided them an informative leaflet explaining the need for cervical cancer prevention.

Among the 53 mothers who admitted to imposing some preconditions before being willing to encourage their daughters’ HPV vaccination, 21 (40%) mothers became more willing to vaccinate their daughters immediately after receiving the cervical cancer prevention linkage explanation provided by their doctor, and seven of the mothers (33%) even returned to the clinic to get their daughter vaccinated during our study period. Logistical regression analysis revealed that having initial preconditions required for their daughters’ HPV vaccination was an independent variable influencing the mothers’ change of willingness to get their daughters vaccinated immediately after receiving the explanation using the leaflet.

We have found that to achieve maximum effectiveness, we can use an appropriate leaflet even under suspension of the governmental recommendation. Our future efforts should be focused on those mothers who are less likely to impose preconditions on their daughter’s vaccination.

Introduction

The age-adjusted incidence of cervical cancer in Japan has been steadily increasing since 2000.Citation1 In response, in the fiscal year (FY) of 2010 the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW) started publically subsidizing HPV vaccinations of all girls aged 13–16. This worked so well that, in April of 2013, HPV vaccination became a national program for girls aged 12–16. However, just two short months later, in June of 2013, there appeared reports in the media of young girls with diverse symptoms observed after HPV vaccination, including widespread pain and movement disorders. The MHLW announced a ‘temporary suspension’ of its recommendation for routine HPV immunization, to be in place until its safety could be ascertained.Citation2 The government’s recommendation suspension has been in place now for almost 8 years. During most of this time, local governments have been unable to send HPV-vaccine recommendation leaflets to girls, and their guardians, as they became eligible for the vaccine. As a result, the HPV vaccination rate in Japanese females has dramatically decreased, from a peak of almost 70% in FY 2010–2012 to nearly 0% today. The HPV vaccine status of a female in Japan has now become almost completely dependent on her fortunate/unfortunate FY of birth.Citation3–6

During the 8 years of this suspension, data on the unparalleled safety and efficacy of HPV vaccines have been accumulating in Japan and overseas.Citation7–10 Meanwhile, the MHLW has suggested that local governments should send to the age-targeted girls and their guardians, not HPV-vaccine recommendation leaflets, but rather ‘informational leaflets’ regarding the HPV vaccine. In one such city, which did send information leaflets to its girls and their guardians, the vaccination rate rose from 0% to roughly 10%;Citation11 however, this is still significantly lower than the 70% rate that had been achieved just before the suspension announcement.

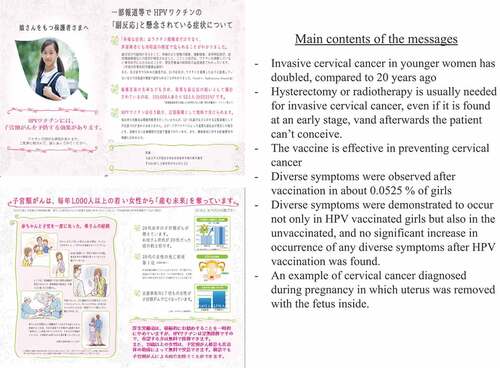

The MHLW has recently, in October 2020, extensively revised its HPV vaccine leaflet, from one leaving a ‘negative impression’, with an emphasis on the diverse events, to one with a ‘positive image’, with an emphasis on its efficacy. We had previously verified by survey the impact of the contents of these leaflets on the intention of mothers to get their daughters vaccinated.Citation12 As expected, our experimental leaflet – one that actively recommended HPV vaccination – motivated mothers to inoculate their daughters significantly better than MHLW’s leaflet focusing in on the diverse symptoms after HPV vaccination (2.2% better motivation versus 9.2%, respectively; p < .001). Our experimental leaflet can’t be used publicly yet because of the continuing MHLW ban on any official recommendations for the vaccine. Another leaflet that we created, which was positively informative, but which was not regarded as an active recommendation of HPV vaccination, increased the mothers’ vaccination intentions from 2.2% to 5.0%, but this was not a ‘statistically significant’ improvement. Another of our studies revealed that even MHLW’s former leaflet, with its negative image, could significantly increase the mothers’ intention to get their daughters inoculated – if it was their doctors explaining the contents to them.Citation13

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the potential of using our positively informative leaflet to guide their doctor’s explanation of cervical cancer and the benefits of the HPV vaccine. This leaflet, developed in a previous study.Citation12 is not to be regarded as being an active recommendation of HPV vaccination. This positive-image-leaflet doctor-presentation strategy might lead to a better acceptance of the HPV vaccine while we are still under the suspension of a governmental recommendation for it.

Methods

Survey questionnaire #1

From April to December of 2020, a questionnaire survey was conducted in the Tsubaki Women’s Clinic of Matsuyama, Japan. Among the patients who came to the clinic, the survey was given only to the women guardians/parents of girls of the HPV-vaccine-targeted ages of 12–16. Our survey investigated the mothers’ attitudes before and after they had the leaflet explained to them by their doctor. The leaflet was about cervical cancer and its prevention; it was positively informative but was not regarded as an active recommendation of HPV vaccination. We took care to ensure that the leaflet could be publicly distributed despite the suspended governmental recommendation and its prohibition against such official recommendation by other government entities (). If necessary, other data was also presented to the mothers. The questionnaire consisted of two questions: Q-(A): What preconditions have you imposed on your daughter’s HPV vaccination? (before receiving the leaflet explanation), and Q-(B): What do you think now about vaccinating your daughter (after receiving the leaflet explanation)?

In the survey, questions probing their decision-making capacity were also included. Q1: Do you usually feel it difficult to make decisions in your daily life?; Q2: Does it take much time for you to decide something?; Q3: Do you try to avoid making any decisions as much as possible?; Q4: Do you tend to leave decisions to others?; Q5: Do you often change your decision later?

We analyzed the association between the mothers’ decision-making capacity and any preconditions they required before promoting/permitting their daughters’ HPV vaccination. Factors that could influence the mothers’ intention to get their daughters vaccinated were also investigated using a multivariate analysis tool.

Next, after excluding mothers whose daughters were already vaccinated, and those who answered that they would vaccinate their daughters soon without requiring any specific preconditions, we analyzed the leaflet-explanation-induced changes in the mothers’ intention to get their daughters vaccinated. Using a logistic regression model, we conducted a multivariate analysis for factors influencing the mothers’ willingness to get their daughters vaccinated immediately after receiving an explanation using the leaflet.

Since the present study was not a validation one, but an exploratory one, we did not set a required number of cases, but we aimed to enroll a minimum of 50 mothers within the study period of 8 months to adequately analyze their intention to vaccinate their daughters.

Questionnaire survey #2

A second questionnaire survey was conducted to study the mothers who took their daughters to the Tsubaki Women’s Clinic to get HPV-vaccinated during the survey study period. We asked them why they had decided to get their daughters vaccinated. These mothers overlapped in part with those who had been educated about cervical cancer and its prevention using the leaflet in Survey #1.

Statistics

The chi-square test was used for statistical analysis of the association between the mothers’ decision-making capacity and their preconditions required for getting their daughters vaccinated. The level of statistical significance was set at p = .05. Multivariate logistical regression analysis was conducted using MedCalc statistical software to evaluate the factors that influenced the mothers’ intention to get their daughters vaccinated after receiving an explanation using the leaflet.

Results

Characteristics of mothers whose attitude toward their daughters’ HPV vaccination were investigated (Survey 1)

We received responses from 59 women, median age 43 (range 33–53), among whom 54 (92%) had received cervical cancer screening at least once (). Decision-making capacity could be evaluated in only 56 mothers, after the exclusion of three who failed answer those related questions, by assigning them a score from 1 to 7 for the answer to each question (). The median total score was 22 (16–35).

Table 1. Characteristics of the mothers who were investigated for their attitudes toward their daughters’ HPV vaccination (Survey #1)

Table 2. Decision-making capacity of the mothers

Preconditions of the mothers for their daughters’ HPV vaccination

We investigated the HPV vaccination status of the daughters and the preconditions the mothers said they required before they would encourage their daughters’ HPV vaccination – if as yet unvaccinated (). Only one of the 56 daughters (2%) had already been vaccinated. Three mothers (5%) answered that they would soon vaccinate their daughters – without any specific preconditions; 24 mothers (43%) answered that they would vaccinate their daughters if the governmental recommendation would be restarted. One mother (2%) responded that she would inoculate her daughter only after observing the safe and successful inoculation of her daughter’s friends or their acquaintances, and 13 (23%) mothers answered that they would vaccinate their daughters only after many girls of the same generation got inoculated. The association between having various levels of preconditions and their decision-making capacity was not statistically significant (p = .20, by the Chi-square test).

Table 3. Preconditions the mothers have for their daughters’ HPV vaccination at the time of entry to the study versus the decision-making capacity of the mothers

Change of the mothers’ intention to get their daughters vaccinated after receiving explanation using the leaflet

After excluding the one mother whose daughter was already vaccinated, and three mothers who answered that they already would soon vaccinate their daughters without any specific preconditions, and two mothers who did not answer this question, we analyzed for any changes in the mothers’ intention to get their daughters vaccinated after receiving an explanation of cervical cancer and the HPV vaccine using our leaflet (). Among 53 mothers, 21 (40%) strengthened their intention to inoculate their daughters and thought they would be willing to vaccinate their daughters immediately – without any specific preconditions.

Table 4. After receiving an explanation using the leaflet, change in mothers’ intention to get their daughters vaccinated

Logistic regression analysis revealed that the initial preconditions required for their daughters’ HPV vaccination at the time of entry to the study was an independent factor when it came to influencing the mothers’ willingness to get their daughters vaccinated immediately after receiving an explanation using the leaflet. The mothers who would at first inoculate their daughters if the governmental recommendation was resumed significantly increased their intention to get their daughters vaccinated (adjusted OR: 4.51, 95% CI:1.28–15.93, p = .019), compared to those who required additional preconditions including inoculation of their friends, acquaintances, or many girls of the same generation ().

Table 5. Multivariate analysis for the factors that influenced the change in mothers’ willingness to get their daughters vaccinated immediately after receiving an explanation using the leaflet

Reasons for the mothers having taken their daughters to the clinic to get HPV vaccinated (Survey #2)

During the study period, 16 mothers came in to get their daughters HPV vaccinated (). Among them, 8 (50%) were motivated to inoculate their daughters by the leaflet sent from Matsuyama City. Importantly, for seven of the 16 mothers (44%), the explanation by a clinic doctor about cervical cancer and its prevention during Survey #1 was admitted to be the trigger responsible for their daughters’ impending HPV vaccination. In fact, among 21 mothers who answered that they became more willing to inoculate their daughters immediately after their doctor/leaflet interactions during Survey #1, seven mothers (33%) returned to the clinic during our study period to get their daughters vaccinated.

Table 6. Reasons for the mothers having taken their daughters to the clinic to get HPV vaccinated

Discussion

Cervical cancer has been increasing in a younger than usual generation in Japan,Citation1 and this tragedy has been occurring under the continuing suspension of the governmental recommendation for acceptance of a vaccine mostly capable of prevention of that cancer. We have come to the conclusion that a more effective strategy needs to be pursued to penetrate the public’s current high state of hesitancy surrounding the HPV vaccine. We have already demonstrated that sending HPV vaccine information leaflets directly to vaccine-eligible girls and their guardians/parents increase HPV vaccination rates. We found the same success when we revised the information leaflet to provide a more positive and informative tenor about cervical cancer and its prevention. When a doctor participated in providing our leaflet information, these effects were even stronger.Citation11–13

In the present project, we tested a combined strategy of providing an explanation from a doctor about cervical cancer and its prevention using a leaflet which was designed to be more positively informative – but which could not be regarded by a governmental regulatory body as being an active recommendation for HPV vaccination. We first investigated the HPV vaccination status of the daughters of our survey respondents and, if unvaccinated, the preconditions the mothers might require before they would encourage their daughters’ HPV vaccination (). Of the daughters, 2% were already vaccinated, and 5% of the mothers answered that they would vaccinate their daughters soon anyway, without any specific preconditions. The combined percentages, 7%, seemed far higher than the current vaccination rate of less than 1%, suggesting that women visiting the clinic were perhaps already more pre-inclined to have their daughters vaccinated. This pre-inclination finding was consistent with our previous survey.Citation13

We found that the association between the mothers’ preconditions and their decision-making capacity was not statistically significant (p = .20), suggesting that the negative image they had of the HPV vaccine was so strong that it might be beyond their decision-making capacity to overcome.

As for the effectiveness of a doctor personally providing the education from the positively informative leaflet, 40% of the mothers, who would initially have imposed some preconditions, changed their minds, increased their intention to inoculate their daughters, and thought they would do so immediately, even without those preconditions. According to one of our previous studies, when a local government sent information leaflets directly to the girls and their guardians in a very personal way, the effort was rewarded, the local vaccination rate increased from 0% to almost 10%.Citation11 A positive and informative leaflet, one that was not an actual recommendation for HPV vaccination, increased the mothers’ intention to inoculate their daughters significantly, by up to 9.2%.Citation13 Compared to these effects, the impact gained from a combined strategy of an explanation from a doctor about cervical cancer and its prevention, and a leaflet which was positively informative but not a recommendation for vaccination, was extremely high, suggesting that this strategy might be a potential tool to penetrate the high degree of HPV vaccine hesitancy in Japan that has accumulated under the continued suspension of the governmental recommendation for the vaccine. This effectiveness was confirmed beyond just the positive survey response; it was supported by the actual act of getting their daughters vaccinated ().

We found that among the mothers who came to get their daughters HPV vaccinated at the Tsubaki Women’s Clinic in Matsuyama City during our study period, 50% were motivated to do so by the revised MHLW leaflet sent from their local government; this supported our theory that a more personalized sending of information leaflets to the targeted girls and their guardians was also an effective strategy ().

Since the leaflet used in this study corresponded to the revised MHLW leaflet, it would be useful to provide appropriate explanations about cervical cancer and the HPV vaccine to the patients and guardians/parents while they are visiting their obstetricians and gynecologists using not only our leaflet but also the revised MHLW leaflet.

Interestingly, logistic regression analysis revealed that the mothers who would inoculate their daughters if the governmental recommendation is resumed significantly increased their intention to get their daughters vaccinated compared to those who required additional preconditions, including inoculation of their friends, acquaintances, or many girls of the same generation (). This result implied that the current delimited effort of educating the targeted girls and their mothers about cervical cancer and the HPV vaccine should be more effectively focused on the mothers who are less likely to impose preconditions on their daughters’ vaccinations, which can be pre-ascertained through a simple interview process with the mothers.

There are some limitations in the present study. Only 59 women who responded to the questionnaire survey were analyzed. The data might be unable to apply to all mothers. Moreover, we could not follow up all the daughters of the women they explained using an informational leaflet.

Strong efforts from various directions will be needed for the re-dissemination of the HPV vaccine under a situation where the government continues to sustain its recommendation suspension. Otherwise, there will be a large increase in the risk for cervical cancers for those girls who fail to be vaccinated.Citation14 We sincerely ask the government to resume its recommendation for the vaccine as soon as possible, and, in addition, to enhance sending appropriate information about HPV vaccine to the targeted girls.

Abbreviations

| HPV | = | human papilloma virus |

| MHLW | = | the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare |

| FY | = | fiscal year |

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

YU received lecture fees and a research fund (grant number J550703673) from Merck Sharp & Dohme. AY received a lecture fee from Merck Sharp & Dohme. TK received a research fund (VT#55166) from Merck Sharp & Dohme.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Osaka University Hospital. Informed consent was obtained by checking the box of “I agree to participate in this survey” by all the participants in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. G.S. Buzard for his constructive critique and editing of our manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Yagi A, Ueda Y, Kakuda M, Tanaka Y, Ikeda S, Matsuzaki S, Kobayashi E, Morishima T, Miyashiro I, Fukui K, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical analysis of cervical cancer using data from the population-based Osaka cancer registry. Cancer Res. 2019;79(6):1252–59. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3109.

- Ikeda S, Ueda Y, Yagi A, Matsuzaki S, Kobayashi E, Kimura T, Miyagi E, Sekine M, Enomoto T, Kudoh K. HPV vaccination in Japan: what is happening in Japan? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18(4):323–25. doi:10.1080/14760584.2019.1584040.

- Hanley SJ, Yoshioka E, Ito Y, Kishi R. HPV vaccination crisis in Japan. Lancet. 2015;385(9987):2571. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61152-7.

- Ueda Y, Enomoto T, Sekine M, Egawa-Takata T, Morimoto A, Kimura T. Japan’s failure to vaccinate girls against human papillomavirus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(3):405–06. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.037.

- Nakagawa S, Ueda Y, Yagi A, Ikeda S, Hiramatsu K, Kimura T. Japanese crisis of HPV vaccination. Int J Pathol Clin Res. 2016;2(2):039. doi:10.23937/2469-5807/1510039.

- Nakagawa S, Ueda Y, Yagi A, Ikeda S, Hiramatsu K, Kimura T. Corrected human papillomavirus vaccination rates for each birth fiscal year in Japan. Cancer Science. 2020;111(6):2156–62. doi:10.1111/cas.14406.

- Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, Wang J, Roth A, Fang F, Sundström K, Dillner J, Sparén P. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1340–48. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917338.

- Ueda Y, Yagi A, Nakayama T, Hirai K, Ikeda S, Sekine M, Miyagi E, Enomoto T. Dynamic changes in Japan’s prevalence of abnormal findings in cervical cytology depending on birth year. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5612. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-23947-6.

- Arbyn M, Xu L. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic HPV vaccines. A Cochrane Rev Randomized Trials Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17:1085–91.

- Suzuki S, Hosono A. No association between HPV vaccine and reported post-vaccination symptoms in Japanese young women: results of the Nagoya study. Papillomavirus Res.2018;(5):96–103.

- Ueda Y, Yagi A, Abe H, Nakagawa S, Minekawa R, Kuroki H, Miwa A, Kimura T. The last strategy for re-dissemination of HPV vaccination in Japan while still under the suspension of the governmental recommendation. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):16091. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-73120-1.

- Yagi A, Ueda Y, Masuda T, Ikeda S, Miyatake T, Nakagawa S, Hirai K, Nakayama T, Miyagi E, Enomoto T, et al. Japanese mothers’ intention to HPV vaccinate their daughters: how has it changed over time because of the prolonged suspension of the governmental recommendation? Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8(3):502. doi:10.3390/vaccines8030502.

- Shiomi M, Ueda Y, Abe H, Yagi A, Sakiyama K, Kimura T, Tanaka Y, Ohmichi M, Ichimura T, Sumi T, et al. A survey of Japanese mothers on the effectiveness of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare’s revised HPV vaccine leaflet. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(10):2555–58. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1723362.

- Yagi A, Ueda Y, Nakagawa S, Ikeda S, Tanaka Y, Sekine M, Miyagi E, Enomoto T, Kimura T. Potential for cervical cancer incidence and death resulting from Japan’s current policy of prolonged suspension of its governmental recommendation of the HPV vaccine. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):15945. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-73106-z.