ABSTRACT

Background

Delay in receiving the vaccination is a major public health problem that has been associated with vaccine-preventable disease epidemics. In Ethiopia, many children have not received the benefits of age-appropriate vaccination; thus more than 90% of child deaths are largely due to preventable communicable diseases.

Objective

The present study assessed the magnitude and associated factors of delayed vaccination among 12–23 months old children in Tigray, Ethiopia.

Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study was carried out among 393, 12–23 months old children from July 1 to 30, 2018. Data were collected using a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire includes socio-demographic, economic factors, Maternal/caregiver factors, Child’s factors, and Service-related factors. We applied bivariable and multivariable logistic regression to determine predictors for delayed Vaccination. The odds ratio with 95% CI was computed to evaluate the strength of the association.

Results

393 participants were involved in the study. The magnitude of delayed vaccination was 29.5% (95% CI 26.7–45). Mothers who attend tertiary (University/college) education (AOR 0.169, 95% CI 0.032–0.882), and secondary education (AOR 0.269, 95% CI 0.114–0.636) had the protective effect of delayed vaccination. But the sickness of a child (AOR = 11.8, 95% CI 6.16–22.65) was a risk for delayed vaccination.

Conclusions

The magnitude of delayed vaccination was high, particularly among participants with Mother’s education, and Mother’s consideration in the child’s wellness to take the vaccine. This implies that it is important to give emphasis, especially for the mothers who have an uneducated and sick child to increase awareness about the advantage of vaccination, which will improve on-time vaccination.

Introduction

Vaccine-preventable diseases cause over three million childhood deaths each year globally especially in developing countries.Citation1,Citation2 Of the nearly 8.8 million yearly deaths of under-five children greater than 20% are due to vaccine-preventable diseases (VPD).Citation3 Vaccine-preventable diseases (VPD) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in children under five years of age in developing countries including Ethiopia.Citation4 Ethiopia has experienced many outbreaks and hence morbidity and mortality from vaccine-preventable diseases (VPD).Citation5 According to Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS) 2016; childhood mortality rates have declined since 2000, despite that, infant and under-5 mortality rate in Ethiopia was 48/1000 and 67/1000 respectively.Citation6 Vaccination is the most important public health interference for vaccine-preventable diseases (VPD).Citation7 It presently averts more than 2.5 million deaths every year in all age groups from diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough), and measles.Citation8,Citation9 In Ethiopia nearly 4 in 10 children aged 12–23 months have received all eight basic vaccinations; single doses of BCG and measles and three doses for each of Pentavalent, PCV, Rota, and polio vaccine. Vaccination is a key element of the health extension program package.

The country’s vaccination schedule for the above-listed vaccines strictly follows the WHO recommendations for developing countries, such as Ethiopia.Citation5 The National vaccination schedule for infants in Ethiopia is shown in ().

Table 1. National immunization schedules for infants in Ethiopia

The use of static sites, outreach sites, and mobile teams are recommended as appropriate strategies for delivering vaccination services.Citation5

The Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS) surveys have shown steady progress in Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) coverage. The percentage of children age 12–23 months who received all basic vaccinations increased from 14% in 2000 to 20% in 2005, 24% in 2011, and 39% in 2016. However, the proportion of children age 12–23 months with no vaccination decreased from 24% in 2005 to 16% in 2016.Citation6 However, timely and full vaccination coverage has not been completed in Ethiopia as planned.Citation10 In Edagahamus, the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) schedule is not applied as National advice for the timing of delivery; as a result, many children don’t receive the benefits of timely and age-appropriate vaccination. So, improving timely and age-appropriate vaccination delivery would require better understanding of the reasons for the delay.Citation11 Delay in receiving vaccination have been reported globally.Citation12 In the United States of America, up to 40% of parents delay or refuse their children’s vaccine.Citation13 63.3% of the Gambian children had a delay in the mentioned age range to receive at least one of the studied vaccines.Citation1 In Uganda, less than half of all children received all vaccines within the recommended time.Citation14 According to different kinds of literature, factors that are associated with delayed vaccination includes; marital status, educational status, occupation, income, service accessibility, transportation, distance, place of birth, birth order, number of children in the household, sickness of the child, Forget/don’t know the due date and so on.Citation1,Citation14–16 Today, parents’ vaccine hesitancy may have been increased by celebrities’ public airing of their concerns about vaccines.Citation1,Citation14–16 Parents commonly mention the fear of side effects as a reason for not vaccinating their children; e.g., in Liberia, Somalia, Armenia. In some cases, an older sibling’s experience of side effects leads to parents refused vaccination for younger children. Little is known about delayed vaccination and as per the investigators; no studies were conducted to assess delayed vaccination. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the magnitude and factors associated with delayed vaccination among 12–23 months old children in Edagahamus.

Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study design was employed among children 12–23 months old from July 1 to 30, 2018 in Edagahamus city, Tigray, and North Ethiopia. Edagahamus city is located 885 km away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, and 105 km from Mekele capital city of Tigray regional state. The total population of the Edagahamus city was 21,993; from those 10,031 were male, 11,962 were female and 795 were under two-year children (2006/2012 census). There are 32 health professionals and 13 health extension workers (HEWs) in the city with one health center and 4 health posts supported by 9 outreach vaccination sites that routinely provide immunization services. The health service currently reaches about 89% of the population including outreach programs and health posts.

Mothers/caretakers who have a vaccination card were included in the study. Critically ill mothers/caretakers who were unable to respond and did not complete their vaccination (drop out) were excluded from the study.

The sample size was determined using a single proportion calculation formula assuming the following parameters: 63.3% prevalence of children who had delayed vaccination in the Gambia,Citation1 95% CI (Ζ1-α/2) = 1.96), 5% degree of marginal error (d), and 10% non-response rate, and the minimum required sample size was 393. A simple random sampling technique was employed to recruit study respondents. Using a sampling frame obtained from the health extension workers. When two or more eligible participants are present in a household, we selected one eligible participant using a lottery method. Finally, each eligible study participant was contacted through the house to house visits. A second visit was done in case a mother was absent in the house during the first visit. If the mother is not available for the second time, a neighbor’s mother with a child was contacted.

BCG (birth – 8 weeks), Penta1, PCV1, Rota1 and OPV1 (6 weeks – 14 weeks); Penta2, PCV2, Rota2 and OPV2 (10 weeks – 18 weeks); Penta3, PCV3, and OPV3 (14 weeks – 24 weeks)] and measles vaccine (9 months – 11 months). Timeliness of vaccination of a particular antigen was assessed against the WHO recommended range as already indicated above and Children who have delayed at receiving at least one vaccine considered delayed.Citation1

Timely: Was measured if a child was vaccinated within the recommended period above. Delayed: if received after the window period. Penta-1 to Penta-3 dropout rate: the % of children vaccinated for Penta-1 who defaulted for Penta-3. BCG to Measles dropout rate: the % of children vaccinated for BCG who defaulted for measles.

Health Extension Worker: was defined as in Ethiopia, against a backdrop of acute physician shortage, Health Extension Workers are assigned to local health posts and provide a package of essential interventions to meet population health needs at this level. Through the national Health Extension Program, HEWs are recruited among high school graduates in local communities and undergo a one-year training program to deliver a package of preventive and basic curative services that fall under four main components: hygiene and environmental sanitation; family health services; disease prevention and control; and health education and communication.Citation17,Citation18

Data were collected by using an interviewer-administered and structured questionnaire adapted from the WHO survey questions. The questionnaire includes socio-demographic, economic factors, Maternal/caregiver factors, Child’s factors, and Service-related factors. Three data collectors and supervisors were recruited and they were given rigorous training for two days. The supervisors followed the process of data collection, checked the data completeness consistency, and communicate with principal investigators on daily basis.

Data were entered into Epi-info 7 and then exported to SPSS version 20.00 for analysis. We performed descriptive and inferential statistics. Tables, statements, and graphs were used to present the findings of the analyzed data. Bivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to see the crude association between the factors and outcome variables and select candidate variables (variables with p-value < 0.2) to multivariable logistic regression. Adjusted odds ratio with 95% of CI was calculated and P-values less than 0.05 in the multivariable logistic regression were considered as a significant association.

Results

Socio-demographic character of the study participants

A total of 393 mothers of children aged between 12–23 months old were interviewed from four kebeles, with a response rate of 100%. Out of the total study subjects, 222 (56.5%) have children aged 11–17 months, while 171 (43.5%) were aged 18–23 months. The mean (±SD) age of the children was 17(± 6) months old. Female children were 208 (52.9%) of the total study subjects. The age range of mothers included in the study was 17–43 years, which is a childbearing age range. The mean (± SD) age of the mothers was 29.4 (±5.3) years old. ()

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents in Edagahamus, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2018 (n = 393)

Characteristics related to mother

Overall 327 (83.2%) of mothers know the Vaccination schedule. A total of 278 (70.7%) of the mothers got health education, particularly about Vaccination during antenatal and postnatal care while they were pregnant and after the birth of the child. ()

Table 3. Distribution of maternity-related characteristics of Edagahamus, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2018 (n = 393)

Health service-related characteristics

Overall 251 (63.9%) of mothers Satisfied with the practice of providers About 246 (62.6%) mothers get advice during the Vaccination period on adverse events following vaccination ().

Table 4. Distribution of service-related characteristics of Edagahamus, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2018 (n = 393)

The magnitude of age untimely vaccination

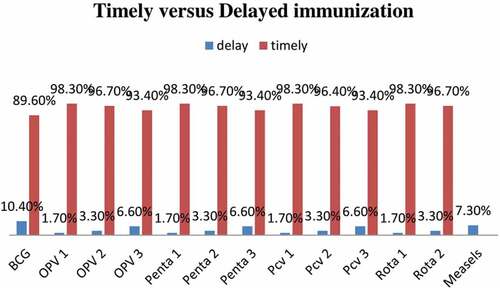

From the total respondents 116 (29.5%, 95% CI26.7%-45%) had experienced a delay in at least one of their Vaccination. For BCG 41 (10.4%) of the respondents presented after the age of 8 weeks and delayed for up to two months. For the first dose of Pentavalent, PCV, Rota, and polio vaccines 7 (1.7%) of the respondents presented after the age of 14 weeks and delayed for up to one month and a half. For the second dose of Pentavalent, PCV, Rota, and polio vaccines 13 (3.3%) of the respondents presented after the age of 18 weeks and delayed for up to two months. For the third dose of Pentavalent, PCV, and polio vaccines 26 (6.6%) of the respondents presented after the age of 24 weeks and delayed for up to two months. For the measles vaccine, 29 (7.3%) of the children presented after the age of 11 months and 5.2% and 1.4% were delayed for up to three and seven months respectively ().

Factors associated with delayed vaccination

In the bivariate logistic regression maternal occupation, marital status, educational status, lack of vaccines, lack of appointment, sickness of the child, and “don’t know“ the due date was associated with delayed Vaccination at p- the value of < 0.2. In multivariate logistic regression analysis sickness of the child, mothers’ educations have a significant association. Mothers who had tertiary education (AOR 0.169, 95% CI 0.032–0.882) and secondary education (AOR 0.269, 95% CI 0.114–0.636) were less likely to delay their infant’s Vaccination compared to those mothers with no education. Child sickness on the appointment day was more likely to delay (AOR 11.36, 95% CI 4.68–27.55) than those healthy ().

Table 5. Factors associated with delayed immunization among 11–23 months old children in Edagahamus Town, Tigray, Ethiopia, and 2018 G.C

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the magnitude and factors associated with Vaccination delay among 12–23 months old children. The overall prevalence of delayed Vaccination among the study participants in this study was 29.5% (95% CI 26.7%-45%). This finding was in line with the other study conducted in Ethiopia and developing countries.Citation19–23 Similarly, the prevalence of delayed Vaccination was in line with a study conducted in developed countries.Citation16,Citation24 This calls for timely vaccination to be considered as another indicator of vaccination program performance to improve on-time administration of vaccination for children. In contrast to this, a study done in low- and middle-income countries,Citation25 Gambia,Citation1 Kampala Uganda,Citation14 45 low-income and middle-income countries,Citation26 Zhejiang province of ChinaCitation27 and Italy.Citation28

This might be due to increased maternal/caregiver’s workload with other domestic activities while the child gets older and thereby can’t remember vaccination appointments of a child. The other possible explanation could be the difference in educational background, degree of knowledge toward Vaccination, the difference in the study population, and Vaccinations are mainly provided by public health nurses and all services are voluntary and free of charge.

More than a quarter (29.3%) of mothers/caretaker was not informative about vaccination schedule and related topics during PNC/ANC. This finding was in line with the other study conducted in Ethiopia and developing countries.Citation23,Citation29 These findings implied that the Ethiopian Government and the Ministry of Health need to plan health education programs about this vaccination schedule and related topics.

The educational status of the mother/caretaker was a predictor for delayed child Vaccination; in this study maternal education beyond the secondary level was positively associated with timeliness. Several studies also support the finding of the higher educational level being related to timely adherence to the vaccination schedules in Southwest Ethiopia,Citation30 Arba Minch town and Zuria District, Southern Ethiopia,Citation31 Hawassa Zuria District of Southern Ethiopia,Citation32 hard-to-reach areas of Ethiopia,Citation33 Mizan Aman town, bench Maji zone, Southwest Ethiopia,Citation34 Somali National Regional State, Ethiopia,Citation35 rural south western Ethiopia,Citation36 and Dessie town, south Wollo zone, Ethiopia.Citation36 Similarly, studies done in developing countries like sub-Saharan Africa,Citation37 31 low and middle-income countries,Citation38 Burkina Faso,Citation37 Nigeria,Citation12 GambiaCitation1 revealed higher educated mothers are more likely to timely adherence to the vaccination schedules than those who did not attend school. The possible reason for this may be related to the fact that the low education level can hinder the caregiver’s communication with health workers and might influence the caregiver’s awareness to seek and take advantage of public health services including child vaccination. This implies that initiatives to empower women and help them understand their advantage child vaccination should target women who are less educated.

The sickness of the children was also associated with delayed vaccination similar to the study done in Nigeria and Shenzhen, China.Citation12,Citation39 This may be around missed opportunities to vaccinate with mild illnesses. Socio-economic status and the number of children in the households were not predictors for delayed child’s Vaccination in this study, which is different from studies in Gambia and Uganda, which indicates income-related factors hindered utilization of Vaccination services so that children’s with several siblings were more likely to have untimely vaccinations, that higher cost and demands can easily discourage to vaccinate their children’s.Citation1,Citation14 This difference could be explained by the fact that free service for Vaccination is implementing in Ethiopia so that higher costs and demands were not a problem among families who participated in this study.

Limitation

This study has the following limitations. First, we did not assess other childhood vaccines like Hib and HBV vaccines separately because they are given at the same time as DPT as a single injection, so their results are likely to be similar to DPT vaccines. Second, children who do not complete their vaccination (drop out) were excluded from the analysis therefore we might have missed some children with delayed vaccinations. Third, even though vaccines are given in the first year of life in Edagahamus City, we did not study the timeliness of these vaccines. Fourth, the performance of the study in only one small city may not be generalized to the total population of the country. Fifth, as some parts of the questionnaire, depended on the memory of respondents may have resulted in recall bias. Sixth, third, because the sample size was small, some of the confidence intervals in the bivariate and multivariate logistic regression were rather wide.

Conclusions

This study confirmed that the magnitude of delayed vaccination for children aged 12–23 months was high (29.5%). Mother education level and misconception about child illness were significant but no received of education at before/during/ post-delivery was equally prevalent so a suggestion about providing more effort to increase education levels regarding the benefit of timely vaccination and the possibility of vaccination with mild infection or illness.

Abbreviations

Acknowledgments

We are highly indebted to all participants of the study, supervisors of data collection, and data collectors for their worthy efforts and participation in this study. We are also thankful for administrative bodies at all levels who endorsed us to undertake this study.

Authors’ contributions

MG and TG designed the study and performed the statistical analysis, drafted the paper, data analysis. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Ethics and consent

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee (IRC), College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Mekele University. A letter of permission was obtained from administrative bodies of the East Tigray Health Department, Edagahamus City, and selected kebeles. A letter of cooperation from kebeles administrators was also secured. Finally, written and verbal consent was obtained from every study participant included in the study during data collection time after explaining the objectives of the study and the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Paper context

The magnitude of Delayed immunization for children aged 12-23 months is high (29.5%) in Edagahamus. Delayed immunizations of children were predicted by the Mother’s education which had the protective effect of delay immunization and consideration of the mother the child was too ill to undertake vaccination when it was due was a risk for delayed immunization.

References

- Odutola A, Afolabi MO, Ogundare EO, Lowe-Jallow YN, Worwui A, Okebe J, Ota MO. Risk factors for delay in age-appropriate vaccinations among Gambian children. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):346. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-1015-9.

- Dayan GH, Shaw KM, Baughman AL, Orellana LC, Forlenza R, Ellis A, Chaui J, Kaplan S, Strebel P. Assessment of delay in age-appropriate vaccination using survival analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(6):561–70. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj074.

- Drain PK. Vaccine preventable diseases and immunization programs. Vol. 2004. Global Health Education Consortium (GHEC): World Health organization (WHO); 2012. Copenhagen Ø, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe Scherfigsvej.https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/107665/E86809.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Atnafu A, Otto K, Herbst CH. The role of mHealth intervention on maternal and child health service delivery: findings from a randomized controlled field trial in rural Ethiopia. mHealth. 2017;3(9):39–39. doi:10.21037/mhealth.2017.08.04.

- Federal Ministry of Health, A.A.. Ethiopia national expanded programme on immunization, comprehensive multi- comprehensive multi-year plan 2016 YEAR PLAN 2016 YEAR PLAN 2016-2020; 2015 Apr. African Population Studies, 30(2).

- EDHS. ETHIOPIA DEMOGRAPHIC HEALTH SURVEY; 2016. Maryland, USA: The DHS Program ICF Rockville. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR328/FR328.pdf

- Mohammed RT. Assessment of factors associated with incomplete immunization among children aged 12-23 months in Ethiopia; 2016. https://etd.uwc.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11394/4989/Mohammed_rt_mph_chs_2015.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Sodha, S.V. and Dietz, V., 2015. Strengthening routine immunization systems to improve global vaccination coverage. Br Med Bull, 113(1), pp.5–14.

- Legesse E, Dechasa W. An assessment of child immunization coverage and its determinants in Sinana District, Southeast Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15(1):31. doi:10.1186/s12887-015-0345-4.

- MOH, E., 2014. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health Health Sector Development Program IV October 2010 Contents. October 2010. https://www.healthy-newbornnetwork.org/hnn-content/uploads/HSDP-IV-FinalDraft-October-2010-2.pdf

- Lieu TA, Black SB, Ray P, Chellino M, Shinefield HR, Adler NE. Risk factors for delayed immunization among children in an HMO. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(10):1621–25. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.10.1621.

- Sadoh AE, Sadoh WE, Uduebor J, Ekpebe P, Iguodala O. Factors contributing to delay in commencement of immunization in Nigerian infants. Tanzan J Health Res. 2013;15(3). doi:10.4314/thrb.v15i3.6.

- Haelle T. Delaying vaccines increases risks—With no added benefits. Scientific American; 2014. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/delaying-vaccines-increases-risks-with-no-added-benefits/

- Babirye JN, Engebretsen IMS, Makumbi F, Fadnes LT, Wamani H, Tylleskar T, Nuwaha F. Timeliness of childhood vaccinations in Kampala Uganda: a community-based cross-sectional study. PloS One. 2012;7(4):e35432. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035432.

- Mohammadbeigi A, Mokhtari M, Zahraei SM, Eshrati B, Rejali M. Survival analysis for predictive factors of delay vaccination in Iranian children. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6. doi:10.4103/2008-7802.170868.

- Riise ØR, Laake, I, Bergsaker, MAR, Nøkleby, H, Haugen, IL, Storsæter, J. Monitoring of timely and delayed vaccinations: a nation-wide registry-based study of Norwegian children aged< 2 years. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15(1):1–8.

- Organization, W.H. and Unicef. Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: a guide for essential practice; 2015. https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-06/mps%20pcpnc.pdf

- ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR AND HUMAN DECISION PROCESSES 50, 179-211 1991 The Theory of Planned Behavior ICEK AJZEN University of Massachusetts at Amherst Address correspondence and reprint requests to Icek Ajzen. Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst (MA 01003-0034).

- Marefiaw TA, Yenesew MA, Mihirete KM. Age-appropriate vaccination coverage and its associated factors for pentavalent 1-3 and measles vaccine doses, in northeast Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. PloS One. 2019;14(8):e0218470. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0218470.

- Gibson DG, Ochieng B, Kagucia EW, Obor D, Odhiambo F, O’Brien KL, Feikin DR. Individual level determinants for not receiving immunization, receiving immunization with delay, and being severely underimmunized among rural western Kenyan children. Vaccine. 2015;33(48):6778–85. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.021.

- Ouédraogo, N., Kagoné, M., Sié, A., Becher, H. and Müller, O., 2013. Timeliness and Out-of-Sequence Vaccination among Young Children in Burkina Faso—Analysis of Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) Data. Int J Trop Dis Heal, 3, pp.45–56.

- Delrieu I, Gessner BD, Baril L, Roset Bahmanyar E. From current vaccine recommendations to everyday practices: an analysis in five sub-Saharan African countries. Vaccine. 2015;33(51):7290–98. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.107.

- Mekonnen ZA, Gelaye KA, Were MC, Tilahun B. Timely completion of vaccination and its determinants among children in northwest, Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–13. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08935-8.

- Smith PJ, Humiston SG, Marcuse EK, Zhao Z, Dorell CG, Howes C, Hibbs B. Parental delay or refusal of vaccine doses, childhood vaccination coverage at 24 months of age, and the health belief model. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(2_suppl):135–46. doi:10.1177/00333549111260S215.

- Masters NB, Wagner AL, Boulton ML. Vaccination timeliness and delay in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the literature, 2007-2017. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(12):2790–805. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1616503.

- Clark A, Sanderson C. Timing of children’s vaccinations in 45 low-income and middle-income countries: an analysis of survey data. The Lancet. 2009;373(9674):1543–49. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60317-2.

- Hu Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Liang H, Chen Z. Measles vaccination coverage, determinants of delayed vaccination and reasons for non-vaccination among children aged 24–35 months in Zhejiang province, China. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6226-7.

- Adamo G, Sturabotti G, Baccolini V, De Soccio P, Prencipe GP, Bella A, Magurano F, Iannazzo S, Villari P, Marzuillo C, et al. Regional reports for the subnational monitoring of measles elimination in Italy and the identification of local barriers to the attainment of the elimination goal. PloS One. 2018;13(10):e0205147. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205147.

- Fenta SM, Biresaw HB, Fentaw KD, Gebremichael SG. Determinants of full childhood immunization among children aged 12–23 months in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis using Demographic and Health Survey Data. Trop Med Health. 2021;49(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s41182-021-00319-x.

- Asfaw AG, Koye DN, Demssie AF, Zeleke EG, Gelaw YA. Determinants of default to fully completion of immunization among children aged 12 to 23 months in south Ethiopia: unmatched case-control study. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;23(1). doi:10.11604/pamj.2016.23.100.7879.

- Animaw W, Taye W, Merdekios B, Tilahun M, Ayele G. Expanded program of immunization coverage and associated factors among children age 12–23 months in Arba Minch town and Zuria District, Southern Ethiopia, 2013. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-464.

- Tesfaye, F., Tamiso, A., Birhan, Y. and Tadele, T., 2014. Predictors of Immunization Defaulting among Children Age 12–23 Months in Hawassa Zuria District of Southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Public Health Science, 3(3), pp.185–93.

- Girmay A, Dadi AF. Full immunization coverage and associated factors among children aged 12-23 months in a hard-to-reach areas of Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr. 2019;2019:1–8. doi:10.1155/2019/1924941.

- Meleko A, Geremew M, Birhanu F. Assessment of child immunization coverage and associated factors with full vaccination among children aged 12–23 months at Mizan Aman town, bench Maji zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr. 2017;2017:1–11. doi:10.1155/2017/7976587.

- Mohamud AN, Feleke A, Worku W, Kifle M, Sharma HR. Immunization coverage of 12–23 months old children and associated factors in Jigjiga District, Somali National Regional State, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–9.

- Wado YD, Afework MF, Hindin MJ. Childhood vaccination in rural southwestern Ethiopia: the nexus with demographic factors and women’s autonomy. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17(Suppl 1):9. doi:10.11694/pamj.supp.2014.17.1.3135.

- Schoeps A, Ouédraogo N, Kagoné M, Sié A, Müller O, Becher H. Socio-demographic determinants of timely adherence to BCG, Penta3, measles, and complete vaccination schedule in Burkina Faso. Vaccine. 2013;32(1):96–102. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.063.

- Akmatov MK, Mikolajczyk RT. Timeliness of childhood vaccinations in 31 low and middle-income countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(7):e14–e14. doi:10.1136/jech.2010.124651.

- Lin W, Xiong Y, Tang H, Chen B, Ni J. Factors associated with delayed measles vaccination among children in Shenzhen, China: a case-control study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(12):3601–06. doi:10.4161/21645515.2014.979687.