ABSTRACT

This study aimed to investigate nursing students’ perspectives regarding the role of nurses as HPV vaccine advocates and their perception of barriers to advocacy. A cross-sectional study using a Web-based survey was sent out to all undergraduate nursing students enrolled at the Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China. A total of 1,041 students responded to the survey. In total, 58.0% of students expressed an intent to advocate HPV vaccines as a counselor and 56.4% as an HPV information provider in their future practice. However, 33.4% stated that they do not intend to be HPV vaccine advocates. Grade 1 students, students from homes with higher annual household incomes and those with a higher level of knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccination expressed higher intentions to advocate for HPV vaccines as a counselor. Students who have a higher level of knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccination and have received HPV vaccines reported a higher advocacy intent in the provision of HPV information. The main perceived barriers in HPV vaccine advocacy include inadequate training (87.1%) and insufficient HPV-related knowledge (84.8%); also, anxious patients may not feel comfortable with nurses discussing HPV vaccination (52.8%). Nurses are uniquely positioned to nurture patient HPV vaccine acceptance and maybe the key strategy to increase HPV vaccination coverage in China. Institutional support is needed to train nurses as HPV vaccine advocates and should focus on enhancing HPV-related knowledge while destigmatising the embarrassment around discussing HPV-related issues with patients.

Introduction

After approximately 10 years of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine being available in many countries around the world, the vaccines were finally approved in mainland China in 2016. The Chinese authorities have approved Cervarix, a 2-valent vaccine, for girls aged 9–25 years, and Gardasil, a 4-valent vaccine, for women aged 20–45 years. HPV vaccination has not yet been recommended for men in China. A potential serious concern is that despite the substantial morbidity and mortality of cervical cancer cases caused by HPV, both the HPV vaccination and cervical screening coverage in China remain low.Citation1 As of August 2020, there is no national HPV vaccination programme in China.Citation2 HPV vaccination is currently not mandatory; it is on a voluntary basis and vaccination is self-paid.Citation3 The high price of HPV vaccine in China and the vaccine not being listed in the national immunization program are among the barriers to the uptake of the HPV vaccine.Citation3 Expert opinions and evidence from research are pointing toward the need for further HPV vaccination education intervention and promotion in China.Citation3–5 The overall infection rate of high-risk HPV in women was 19.0%Citation6 and the national overall prevalence of HPV infection was 15.54%;Citation7 hence, HPV immunization in China should be accelerated.

In line with previous research reporting that physicians serving as HPV vaccine advocates are important in enhancing HPV vaccine uptake,Citation8 nurses, who are by far the largest part of the workforce in most health-care facilities, are particularly well suited to serving as HPV vaccine advocates and can potentially reach a larger group of patients. Although the role of nurses as patient advocates is well recognized in China, their role as HPV vaccine advocates is not fully delineated or widely embraced. Nurses are at the forefront of health-care provision and can significantly influence the delivery of healthcare. They are vital to the functionality of the health-care system and are ideal patient advocates because of their regular contact with patients.Citation9,Citation10 The nature of the nursing professional authority enhances nurses’ ability to influence vaccine decisions; as a result, patients commonly seek out nurses for health-related advice.Citation11 Nurses have been regarded as ideal primary contacts for immunization information and concerns as well as immunization adherence.Citation11,Citation12 In the US, nurses are the primary sources of information and guidance about recommended student vaccinations.Citation13 In the case of the HPV vaccination, school nurses are important in educating parents about the importance of HPV vaccination in teens and simultaneously advocate cervical cancer screening and prevention.Citation14 Patients regard nurses as an approachable and informative resource for HPV vaccination and other sexually transmitted infections.Citation15 Furthermore, nurses were viewed as well suited to educating students, patients, and parents in HPV-related health problems and prevention.Citation11

The current nursing education and training in China may not sufficiently prepare students for the role of HPV vaccine advocates when they enter the healthcare workforce. It is empirical to evaluate whether it is feasible to build advocacy capacity among the nurses to significantly facilitate HPV vaccine uptake in China. We believe that effective HPV vaccination advocacy requires the provision of appropriate training and mentorship. As nursing students are the future nursing workforce, education and training that foster their enthusiasm as HPV vaccine advocates should begin during their undergraduate years. Therefore, identifying current gaps in HPV-related knowledge and attitudes and advocacy intent among undergraduate nursing students is the most important step toward achieving successful and sustainable HPV vaccine advocacy capacity among nurses. As HPV infection is known to occur primarily transmitted through sexual contact, we are also of the opinion that HPV vaccine advocacy should go beyond just providing information or recommendations to patients. The provision of counseling to prevent HPV vaccine hesitancy is essential due to the complex pathogenesis of cervical cancer development and sensitivity surrounding HPV infections.

Herein, the first objective of this study is to determine the HPV vaccine advocacy intent (both in counseling patients and the provision of HPV information) among undergraduate nursing students, and to investigate the influence of HPV-related knowledge and attitudes on advocacy intention. The second objective of this study is to assess students’ perceptions regarding barriers to HPV vaccine advocacy.

Materials and methods

Study participants and design

The sample was recruited from undergraduate nursing students at the Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China. The study adopted a cross-sectional study design using a Web-based survey. The survey was anonymous and self-administered online with a link to the questionnaire being sent to all registered nursing students. In total there were 1,267 nursing students in years 1 to 4 at the university who received the invitation to participate in the survey. The sample size was calculated based on a response rate of 50%, confidence interval of 99%, margin error of 5%, and a total of 1,267 student population. The total sample size required for this study was 436. The sample size was multiplied by the predicted design effect of two to account for the use of convenience sampling and an online survey.Citation16 Hence the minimum survey sample size was set to 872 (436 x 2) participants.

Measures

The survey consisted of five sections, which assessed the following: i) students’ socio-demographic background and HPV vaccination status, ii) knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccination, iii) perceived susceptibility to HPV infection, perceived severity of HPV infection, and perceived benefits of HPV vaccination, iv) advocacy intent and v) perceived barriers in HPV vaccine advocacy.

Knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccination

Knowledge questions consisted of a total of 20 items. Response options were true, false, and don’t know. A correct response was given a score of 1 and an incorrect or don’t know response was scored as 0. The possible total knowledge score ranged from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating better knowledge. The items of the knowledge questions had a reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.946.

Attitudes toward HPV and HPV vaccination

The questionnaire assessed students’ attitudes toward HPV and HPV vaccination (three items) and was developed based on Health Belief Model (HBM) as a theoretical framework.Citation17 The HBM is an established model commonly used to identify determinations of HPV vaccination behavior.Citation18 The questions probed perceived susceptibility to HPV infection, perceived severity of HPV infection, and perceived benefits of HPV vaccination. Response options were agree and disagree. The knowledge and attitudes questions items were adapted from a previous study.Citation19

Advocacy intent

Advocacy intent questioned students about their intention to become HPV vaccine advocates by 1) counseling patients about HPV vaccination and 2) providing HPV information or vaccine recommendations in their future career practice. Response options were strongly agree, agree, disagree and strongly disagree.

Perceived barriers in HPV vaccine advocacy

Self-developed six-item questions were used to assess students’ perceptions toward barriers in carrying out advocacy work in their future career practice. The response options were on a four-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree), with each assigned a point value, from 1 to 4. The possible total barrier score ranged from 6 to 24, with higher scores indicating higher levels of barriers. The 6 items of the barrier questions had a reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.747.

The English version of the questionnaire is shown in Appendix A. The questionnaire was content-validated by several panel experts in the field of nursing education and health research to ensure the relevance and clarity of the questions. A draft questionnaire was pilot-tested for comprehension and ease of completion with a group of 20 students not included in the final study population.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee at the Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China. Students were informed that their participation was voluntary. Online informed consent was obtained from study participants.

Statistical analyses

Internal consistency was tested using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The normality of total knowledge and barrier scores were checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The dichotomization of total knowledge and barrier scores was performed using a median split to form high and low score groups.Citation20 Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate factors influencing advocacy intent (both intention to counsel patients and to provide HPV information) and levels of barriers in advocacy. All variables found to have a statistically significant association (two-tailed, p-value < 0.05) in the univariate analyses were entered into multivariable logistic regression analyses via the forced-entry method.Citation21 Odds ratios (OR), 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) and p-values were calculated for each independent variable. The model fit was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test.Citation22 The Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic indicates a poor fit if the significance value is less than 0.05.

Results

A total of 1,041 complete responses were received between 18 December 2019 and 1 December 2020; the response rate was 82.2%. The summary of the characteristics of the respondents is provided in . Although the majority of students originated from East China (60.4%), the study sample also consisted of students who originated from the Western (23.3%) and Central (16.2%) regions. The majority of students were from households with annual incomes of below CNY¥50,000 (50.8%) and between CNY¥50,000 and CNY¥120,000 (35.4%). Only 7.5% (n = 78) have received HPV vaccines.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and factors associated with advocacy intent (N = 1041)

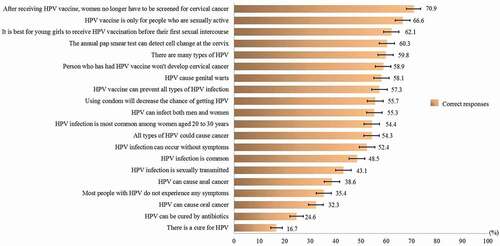

shows the proportion of correct responses to the knowledge items. Almost two-thirds of the students were not aware that HPV infection can occur without any symptoms (64.6%). A large proportion of the study participants were not aware that there is no cure for HPV infection (83.3%) and that it cannot be cured by antibiotics (75.4%). In total, 70.9% of students were aware that women who have been vaccinated against HPV still need to be screened for cervical cancer. The mean total knowledge score was 10.1 (SD ± 6.0) out of a possible score of 20, and the median was 12 (interquartile range, IQR, 5–15). On checking the normality distribution of the knowledge score using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, it was found that the data were not normally distributed (p < .05). The knowledge scores were categorized as a score of 12–20 or 0–11, based on the median split; as such, 50.7% (95%CI 47.6–53.8%) were categorized as having a score of 12–20 and 49.3% (95%CI 46.2–52.4) were categorized as having a score of 0–11. The demographic disparities by knowledge score are shown in Appendix B. Students of higher grades reported significantly higher knowledge scores. Female students and students who originated from the East region reported a higher level of knowledge.

The majority of students have a high perception of women’s susceptibility to contracting HPV (79.3%). With regard to the perception of severity, the majority agreed that the harms associated with HPV infection are severe (93.0%). Regarding the perceived benefit of HPV vaccination, the majority believed that HPV vaccines are highly effective in preventing HPV infection (90.0%) ().

In total, 604 (58.0%) of the students expressed an intent to counsel patients on HPV vaccination. Multivariable regression analysis showed that students in Grade 1 expressed significantly higher intent to counsel patients about HPV vaccination than students in Grade 4 (OR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.02–2.36). Students from households with annual incomes above CNY¥120,000 expressed a significantly higher intent to counsel patients on HPV vaccination than students from households with annual incomes below CNY¥50,000 (OR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.01–2.31). A higher knowledge score (12–20) was also significantly associated with higher intent to counsel patients on HPV vaccination (OR = 1.46, 95% CI 1.10–1.93). A total of 56.4% (n = 590) expressed intent to provide HPV information or vaccine recommendations to patients. Students who have received HPV vaccines (OR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.10–3.06) and have higher knowledge scores (OR = 1.43, 95% CI 1.08–1.88) expressed significantly higher intention to provide HPV information to patients (). The results of the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for both models are shown in the footnote of . Both models demonstrated a good fit for the data.

A total of 348 (33.4%) students reported neither wanting to advocate for counseling provision nor information. The demographic features are shown in Appendix C. Students from households with annual incomes below CNY¥50,000 compared with those above CNY¥120,000 and originated from the West compared to the East region have a significantly higher odds of not intending to be HPV vaccine advocates.

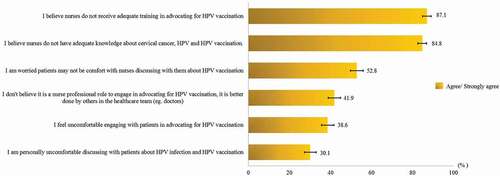

shows the proportion who reported agree/strongly agree in the perception of barriers in carrying out advocacy work in their future career practice. A high proportion perceived inadequate training received in HPV vaccination advocacy (87.1%) and a lack of knowledge about cervical cancer, HPV and HPV vaccination (84.8%). Over half reported that they are worried that patients may not feel comfortable with nurses discussing HPV vaccination (52.8%). In total, 41.9% of students viewed HPV vaccination advocacy to be better when done by other healthcare teams. Participants personally feeling uncomfortable in advocating HPV vaccination (38.6%) and discussing HPV and HPV vaccination with patients (30.1%) were also prominent.

The mean total perceived barriers score was 15.7 (SD ± 2.6). The median was 15 (interquartile range, IQR, 14–17). Upon checking the normality distribution of the barrier score using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, it was found that the data were not normally distributed (p < .05). The barrier scores were categorized as a score of 15–24 or 6–14, based on the median split; as such, 66.0% (95%CI 63.0–68.9) were categorized as having a score of 15–24 and 34.0% (95%CI 31.1–37.0) were categorized as having a score of 6–14. The multivariate logistic regression analysis in showed that students in the older age group expressed a significantly higher perception of barriers in advocacy. Students aged 22–24 years have 2 times higher odds of expressing higher perceived barriers in advocacy (OR = 2.02, 95% CI 1.31–3.12) than those aged below 20 years. Students originated from the West (OR = 1.43, 95CI % 1.03–1.98) and Central China (OR = 1.81, 95% CI 1.22–2.67) expressed higher barriers than those from East China ().

Table 2. Factors associated with perceived barriers in advocacy (N = 1041)

Discussion

As the largest component of the health workforce and having the most interpersonal contact with patients, nurses are in the best position to be HPV vaccine advocates. However, it is unknown whether the role of nurses as HPV vaccine advocates will receive a favorable response from nurses and has the potential to become the key strategy to increase HPV vaccination coverage in China. Little has been investigated about HPV advocacy intent; this study investigated perspectives from undergraduate nursing students who are the potential nursing workforce in executing the advocacy activities. Our study corresponds to the recognition of the professional role and ethical duty of nurses to provide evidence-based information to the public regarding the importance and safety of immunizations.Citation23

Firstly, the finding of the mean knowledge score being around the midpoint on the scale implies that awareness and knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccination among the nursing students was moderate. Of particular importance, this study also found that most of the students have the erroneous belief that HPV infection can be cured and were unaware that HPV can be asymptomatic. The link between HPV infections and other cancers such as oral and anal cancer was also unknown to many nursing students. The level of knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccination among the nursing students in this study is similar to that of a previous study on female health sciences students.Citation19 On a positive note, nursing students have a favorable attitude toward HPV vaccination. The majority have a high perception of susceptibility to HPV infection, perception of disease severity, and positive attitudes toward HPV vaccination.

In the present study, nursing students reported a moderate level of HPV vaccine advocacy intent, with slightly over half reporting an intent to be both HPV vaccine counselors and recommenders. However, one-third reported not wishing to be HPV vaccine advocates. These findings imply the need to further boost nursing students’ interest in HPV vaccine advocacy. In particular, this study demonstrated that students from low-income families reported lower intent to counsel patients on HPV vaccination. This result may imply that students from low socio-economic backgrounds hold a lower career aspiration. Therefore, supporting career aspirations of students from the low socio-economic backgrounds is critical. An important highlight of the study is that lower grade nursing students expressed higher advocacy intention through patient counseling than higher grade students. The low advocacy intention among grade 4 students is a particular concern. They are soon to enter the nursing workforce and should be the target group for interventions to enhance HPV vaccine advocacy intent. The reason for the decreasing intent to become HPV vaccine advocates is unknown and warrants further investigation.

A previous study has shown that practitioners with greater knowledge are more likely to discuss or recommend HPV vaccination to patients.Citation24,Citation25 Similarly, our findings revealed that a higher level of knowledge corresponds to higher advocacy intent. Poor knowledge presumably leads to an increase in the feelings of a lack of self-confidence to carry out advocacy activities. This underlines a crucial need to educate and enhance HPV-related knowledge among undergraduate nursing students to facilitate discussions with patients in the future. We also propose the assessment of HPV-related knowledge gaps among current nursing staff and the provision of professional education initiatives dedicated to current nursing staff in healthcare facilities.

The findings of perception of barriers to carry out advocacy initiatives have important implications for practice. A perceived lack of knowledge as a barrier to advocacy further confirmed that knowledge gaps exist which may hinder their ability and desire to advocate. Sensitivity surrounding the discussion about HPV and HPV vaccination with patients was also an important identified barrier to advocacy. It is well known that the stigma surrounding sexually acquired HPV infection leads to women feeling embarrassed and ashamed of pursuing vaccination as a preventive health behavior.Citation26,Citation27 Advocacy training should also be tailored to reduce stigma in nurse-patient communication around HPV vaccination. At the societal level, there is a need to cultivate a sense of cultural appropriateness of seeking preventive health behavior against sexually transmitted infections.

The regional disparities found in knowledge and advocacy barriers provide tremendously important insights into the future design of advocacy training and implementation at the regional level. It is important to note that regional disparities in cervical cancer are prominent in China, with the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer being higher in Western and Central regions than in Eastern regions.Citation28 Compared to the Eastern region, the Central and Western regions are the least economically developed regions in China. Nursing students from Western and Central regions are potentially important HPV vaccine advocates serving their local communities upon completion of their studies. However, in this study, students from Western and Central regions showed relatively lower levels of knowledge and indicated higher levels of barriers in advocacy. Hence, nursing students from the Western and the Central regions should be targeted by advocacy interventions to facilitate advocacy activities in underserved areas with high cervical cancer rates and low HPV vaccination rates.

It is important to also note that there were no gender disparities in advocacy intent. However, male nursing students reported a lower level of knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccination. It is equally important to promote a better understanding of HPV among male nursing students as they can be HPV vaccine advocates for men. Although HPV vaccination has not yet been recommended for men in China, increasing HPV vaccine knowledge and training male nursing students as HPV vaccine advocates are important to equip them to promote HPV vaccination in men when it is recommended for men in China in the future. Of note, HPV infection is a disease burden for men in China. The national HPV prevalence was 14.5% among heterosexual men in China, while in homosexual men it was reported to be as high as 59.9%.Citation29

Health beliefs toward HPV vaccination were not significantly associated with advocacy intent in the multivariable analyses. However, perceived benefit of HPV vaccination was found to be significantly associated with both HPV vaccine counseling and provision of information in the univariate analyses. This may imply that raising the perception of benefit of HPV vaccination as cervical cancer preventive may likely increase advocacy intent among the nursing students.

Several limitations should be noted when interpreting the results of the present study. The foremost limitation is that the data were collected from students’ self-reports. Inevitably, self-reported advocacy intent may be subjected to desirability response bias and may deviate from actual behavioral intention, thereby potentially resulting in an increased advocacy intention. It should also be noted that intention to carry out HPV advocacy does not necessarily imply actual behavior. Secondly, only undergraduate nursing students from one university in China were surveyed, so the results might not be generalizable to all nursing students in China. It is also important to note that near half of the study participants reported an annual household income of above CNY¥ 50,000. In 2020, China’s per capita disposable income was CNY¥32,189.Citation30 Hence, the majority of our research participants were from families with higher social-economic status. Despite these factors, the nursing student samples were collected from a large public university that consists of students with diverse sociodemographic backgrounds and originated from various regions in China. Finally, our study adopted a cross-sectional design, so we were able to identify associations between exposure and outcomes but could not infer cause and effect.

Conclusion

Nursing students have a moderate level of intention to advocate for HPV vaccine uptake in their future nursing careers. HPV-related knowledge deficiency is pronounced among nursing students and contributes to a lack of advocacy intent. Current evidence suggests that HPV vaccine advocacy training should be incorporated into undergraduate nursing education in nursing schools. It is best to target HPV education and advocacy preparedness catering for final year nursing students as they expressed the lowest advocacy intention despite being close to joining the nursing workforce. More encouragement for students from Western and Eastern regions to carry out HPV vaccination advocacy to help to reduce the burden of cervical cancer in vulnerable populations upon graduating from nursing school is needed. Nursing educators and stakeholders in the healthcare industry should strengthen the advocacy capacity of nurses and support the integration of nurses as active HPV vaccine advocates in the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Xia C, Hu S, Xu X, Zhao X, Qiao Y, Broutet N, Canfell K, Hutubessy R, Zhao F. Projections up to 2100 and a budget optimisation strategy towards cervical cancer elimination in China: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2019 Sep 1;4(9):e462–10. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30162-8.

- Zou Z, Fairley CK, Ong JJ, Hocking J, Canfell K, Ma X, Ma X, Chow EPF, Xu X, Zhang L, et al. Domestic HPV vaccine price and economic returns for cervical cancer prevention in China: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2020 Oct 1;8(10):e1335–44. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30277-1.

- Wei L, Xie X, Liu J, Qiao Y, Zhao F, Wu T, Zhang J, Ma D, Kong B, Chen W, et al. Elimination of cervical cancer: challenges promoting the HPV vaccine in China. Indian J Gynecologic Oncol. 2021 Jun;19(3):1–4. doi:10.1007/s40944-021-00536-6.

- Li J, Zheng H. Coverage of HPV-related information on Chinese social media: a content analysis of articles in Zhihu. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020 Oct 2;16(10):2548–54. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1729028.

- He J, He L. Knowledge of HPV and acceptability of HPV vaccine among women in western China: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Women’s Health. 2018 Dec;18(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/s12905-018-0619-8.

- Li K, Li Q, Song L, Wang D, Yin R. The distribution and prevalence of human papillomavirus in women in mainland China. Cancer. 2019;125:1030–37. doi:10.1002/cncr.32003.

- Zhou H-L, Zhang W, Zhang C-J, Wang S-M, Duan Y-C, Wang J-X, Yang H, Wang X-Y. Prevalence and distribution of human papillomavirus genotypes in Chinese women between 1991 and 2016: a systematic review. J Infect. 2018;76:522–28. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2018.02.008.

- Shahram S, Pielak K. Establishing physician advocates for human papillomavirus vaccination in British Columbia. Can Family Physician. 2012 Sep 1;58(9):e514–20.

- Alex J, Ramjan L, Salamonson Y, Ferguson C. Nurses as key advocates of self-care approaches to chronic disease management. Contemp Nurse. 2020;56(2):101–04. doi:10.1080/10376178.2020.1771191.

- Bird AW. Enhancing patient well-being: advocacy or negotiation? J Med Ethics. 1994 Sep 1;20(3):152–56. doi:10.1136/jme.20.3.152.

- Johnson-Mallard V, Thomas TL, Kostas-Polston EA, Barta M, Lengacher CA, and Rivers D. The nurse’s role in preventing cervical cancer: a cultural framework. Am Nurse Today. 2012 Jul 1;7(7):1–10.

- Wade GH. Nurses as primary advocates for immunization adherence. Mcn. 2014 Nov 1;39(6):351–56. doi:10.1097/NMC.0000000000000083.

- Bennett MP. Ethics and the HPV vaccine: considerations for school nurses. J Sch Nurs. 2008 Oct;24(5):275–83. doi:10.1177/1059840508322380.

- Stone A. Nurses lead charge for HPV prevention. 2020 Feb 24. https://voice.ons.org/advocacy/nurses-lead-charge-for-hpv-prevention .

- American Nurse. The nurse’s role in preventing cervical cancer: a cultural framework. 2012 Jul 11. https://www.myamericannurse.com/the-nurses-role-in-preventing-cervical-cancer-a-cultural-framework/ .

- Wejnert C, Pham H, Krishna N, Le B, DiNenno E. Estimating design effect and calculating sample size for respondent-driven sampling studies of injection drug users in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2012 May;16(4):797–806. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0147-8.

- Champion VL, Skinner CS. The health belief model. Health Behav Health Educ. 2008;4:45–65.

- Ferrer HB, Audrey S, Trotter C, Hickman M. An appraisal of theoretical approaches to examining behaviours in relation to Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination of young women. Prev Med. 2015 Dec 1;81:122–31. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.08.004.

- Lin Y, Lin Z, He F, Hu Z, Zimet GD, Alias H, Wong PL. Factors influencing intention to obtain the HPV vaccine and acceptability of 2-, 4-and 9-valent HPV vaccines: a study of undergraduate female health sciences students in Fujian, China. Vaccine. 2019 Oct 16;37(44):6714–23. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.026.

- MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):19. doi:10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.19.

- Katz MH. Multivariable analysis: a practical guide for clinicians and public health researchers. New York: Cambridge university press; 2011 Mar 10.

- Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. Hoboken , NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2013 Apr 1.

- American Academy of Nursing. Immunization is key to eliminating vaccine-preventable diseases. 2020 Apr 30. https://www.aannet.org/news/policy-news/immunizations-position-statement .

- Chow SN, Soon R, Park JS, Pancharoen C, Qiao YL, Basu P, Ngan HY. Knowledge, attitudes, and communication around human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination amongst urban Asian mothers and physicians. Vaccine. 2010;28:3809–17. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.03.027.

- McSherry LA, O’Leary E, Dombrowski SU, Francis JJ, Martin CM, O’Leary JJ, Sharp L; ATHENS (A Trial of HPV Education and Support) Group. Which primary care practitioners have poor human papillomavirus (HPV) knowledge? A step towards informing the development of professional education initiatives. PloS One. 2018 Dec 13;13(12):e0208482. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208482.

- Siu JY, Fung TK, Leung LH. Social and cultural construction processes involved in HPV vaccine hesitancy among Chinese women: a qualitative study. Int J Equity Health. 2019 Dec;18(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/s12939-019-1052-9.

- Ferrer HB, Trotter C, Hickman M, Audrey S. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination of young women in high-income countries: a qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2014 Dec;14(1):1–22. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-700.

- He R, Zhu B, Liu J, Zhang N, Zhang WH, Mao Y. Women’s cancers in China: a spatio-temporal epidemiology analysis. BMC Women’s Health. 2021 Dec;21(1):1–4. doi:10.1186/s12905-021-01260-1.

- Ma X, Wang Q, Ong JJ, Fairley CK, Su S, Peng P, Jing J, Wang L, Soe NN, Cheng F, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus by geographical regions, sexual orientation and HIV status in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2018;94(6):434–42. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2017-053412.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Households’ Income and Consumption Expenditure in 2020. 2021. http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202101/t20210119_1812523.html.

Appendix A.

Survey questionnaire

PERCEPTION ABOUT NURSES’ ROLE AS HPV VACCINE ADVOCATES

Section A

DEMOGRAPHICS

Section B

HPV VACCINATION STATUS

Section C

KNOWLEDGE ON HPV AND HPV VACCINATION

The following are questions about HPV and HPV vaccination, please answer “True,” “False” or “Don’t know

Section D

ATTITUDES TOWARD HPV AND HPV VACCINATION

Section E

HPV vaccine advocacy intent

Section F

Perceived barriers in advocacy