ABSTRACT

Worldwide, chronic diseases (noncommunicable diseases [NCDs]) cause 41 million (71%) deaths annually. They are the leading cause of mortality in India, contributing to 60% of total deaths each year. Individuals with these diseases are more susceptible to vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) and have an increased risk of associated disease severity and complications. This poses a substantial burden on healthcare systems and economies, exemplified by the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccines are an effective strategy to combat these challenges; however, utilization rates are inadequate. With India running one of the world’s largest COVID-19 vaccination programs, this presents an opportunity to improve vaccination coverage for all VPDs. Here we discuss the burden of VPDs in those with NCDs, the benefit of vaccinations, current challenges and possible strategies that may facilitate implementation and accessibility of vaccination programs. Effective vaccination will have a significant impact on the disease burden of both VPDs and NCDs and beyond.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

What is already known on this topic?

Annually, chronic or noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) cause >40 million deaths worldwide and 60% of all deaths in India

Adults with these diseases are more susceptible to vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs); however, vaccine utilization is inadequate in this population

What is added by this report?

We highlight the benefits of vaccination in adults with NCDs that extend beyond disease prevention

We discuss key challenges in implementing adult vaccination programs and provide practical solutions

What are the implications for public health practice?

Raising awareness about the benefits of vaccinations, particularly for those with NCDs, and providing national guidelines with recommendations from medical societies, will increase vaccine acceptance

Adequate vaccine acceptance will reduce the VPD burden in this vulnerable population

The unmet need

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), also known as chronic diseases, are health-related states that persist over time, limit daily living and activities, and may require ongoing medical attention.Citation1,Citation2 They include cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), chronic respiratory conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma, cancers and diabetes, amongst others.Citation1-3 NCDs are responsible for an estimated 41 million deaths worldwide each year (),Citation4-24 representing 71% of all deaths globally; 77% of these occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).Citation3 By 2030, it is estimated that NCDs will contribute to 52 million deaths annually.Citation25

Table 1. Incidence, YLD, death and YLL in patients with NCDs in 2017.Citation4-7,Citation10,Citation11

Citation13,Citation16,Citation17,Citation19-22,Citation31,Citation32

Due to a decline in fertility rates and increased longevity, world population aging will increase. Adults aged 25–65 years represent 50% of the world’s population, with 8% aged >65 years.Citation8,Citation26 Aging populations and changing lifestyles have led to a rise in the prevalence of NCDs.Citation25,Citation27 Due to immunosenescence, and a host of other age-related factors, such as declining functional reserves and resilience, older people, especially those with NCDs, are more susceptible to vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) and associated complications.Citation8-15 There is a pressing need for developing and implementing protective strategies against VPDs in this population.Citation28

This is profoundly highlighted by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.Citation29 Although the SARS-CoV-2 virus can infect people of all ages, the incidence and severity of infection increase with age.Citation30 COVID-19-related deaths were highest where a greater proportion of the population was aged ≥60 years. Chronic diseases affecting the immune, cardiovascular and respiratory systems that often accompany older age increased the risk, severity and fatality of COVID-19 for many of the older population.Citation29,Citation30

Here we provide an in-depth review of data from around the world highlighting the burden of VPDs in those with NCDs and the urgent need for proactive vaccination programs in this vulnerable population. We also discuss some of the current barriers to vaccines and potential solutions to overcome these, with a focus on the Indian population.

Indian perspective

The world’s population is aging, particularly in LMICs. By 2050, almost two-thirds of the world’s older population will reside in Asia, and by 2030, India is projected to become the most populous country in the world, with >780 million adults aged 25–64 years (53%) and 128.9 million aged ≥65 years (8.8%).Citation26,Citation27

Currently, in India, NCDs are the leading cause of mortality, representing 60% of total deaths in the country and accounting for 15% of all global NCD-related deaths.Citation36,Citation37 In 2016, the largest contribution to the total mortality burden was attributed to CVDs, which were responsible for 31% of all deaths. Chronic respiratory diseases (CRDs) contributed to 7% of total deaths.Citation38 The growing burden of NCDs in India has a significant impact on healthcare systems and economies; >20 million productive life-years are lost annually due to NCDs and associated complications, resulting in a significant loss of annual income (~US $23 billion in 2004). In 2004, Indians spent ~INR 846 billion (~US $12 billion) on out-of-pocket expenditure associated with healthcare costs for NCDs.Citation25,Citation39 Treatment for diabetes costs approximately one-third of the total income of low-income households.Citation25 Thus, there is a critical need to reduce additional healthcare costs, which are significantly impacted by VPDs.

Here we review the growing individual, social and economic burden of some of the key NCDs impacting adults and healthcare systems in India. The diseases discussed are not all-inclusive; for example, cancer is not covered here. Although the literature search was not systematically designed, we use data and evidence from various countries to discuss how adults with NCDs are not only more susceptible to VPDs but are at increased risk of associated disease severity and complications, and we consider how this population would benefit from a routine vaccination program. In India, vaccination programs are primarily focused on children and the adult vaccination coverage is negligible.Citation40 The COVID-19 pandemic has exemplified that there is an urgent need to increase the coverage of adult vaccinations, particularly amongst those with NCDs. We will discuss how potential strategies, such as increasing awareness and education around VPDs and the benefits of vaccines and implementing vaccination guidelines, may help to overcome the barriers against vaccines and, in turn, positively impact quality of life and promote healthy aging.

VPDs in adults with NCDs

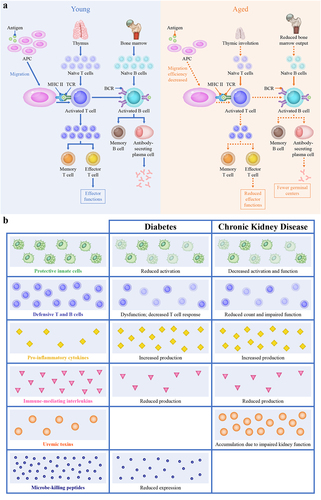

The immune system becomes compromised and dysfunctional with increasing age (immunosenescence), due to a decline in the numbers and functionality of cells that regulate innate and adaptive immune responses ().Citation33 Similarly, the immune system can become compromised in patients with NCDs ().Citation8 This puts the adult population, particularly those with NCDs, at a major disadvantage who, owing to urbanization, globalization, and increasing international travel, are more at risk of contracting VPDs, thus highlighting the need for routine vaccination programs in this patient population.Citation8-15

Figure 1. Immunologic differences in (a) older individuals and (b) those with chronic diseases.

CVD

CVD is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with an estimated 17.8 million deaths in 2017 ().Citation4 In India, CVDs were responsible for 2.2 million deaths, contributing to 23% of total deaths and 44.5% of mortality in adults aged ≥70 years.Citation5,Citation41

Infections and CVD

Influenza and respiratory tract infections are associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in the general population.Citation9,Citation14,Citation15,Citation47 According to a 2015 meta-analysis, patients experiencing acute myocardial infarction (MI) are twice as likely to have had recent influenza or other respiratory tract infections, relative to controls (pooled odds ratio [OR]: 2.01 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.47–2.76]).Citation14 Risk of acute MI or stroke was ~3–5 times greater following respiratory infections than baseline in a case-series analysis of 20,486 patients registered in the UK General Practice Research Database (MI: incidence rate ratio [IRR]: 4.95 [95% CI: 4.43–5.53]; stroke: IRR: 3.19 [95% CI: 2.81–3.62]).Citation15 In a time-series analysis of cardiovascular deaths in New York during influenza season, influenza-like illness was associated with an increase in cardiovascular mortality within 21 days in patients aged ≥65 years.Citation47 In a matched-cohort study of >3,000 patients, risk of CVD was significantly higher among those hospitalized for pneumonia.Citation9

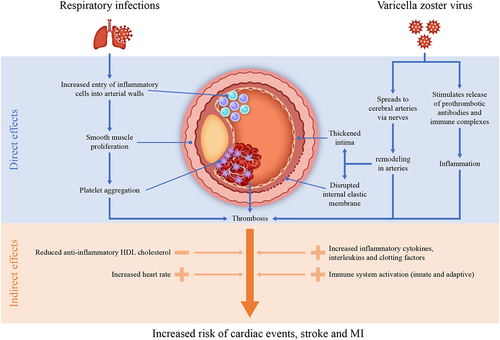

There are two proposed mechanisms by which infections increase the risk of CVD—direct or local effects on vasculature and indirect systemic expression of inflammatory cytokines ().Citation34,Citation42-46

Figure 2. The effect of VPDs.

Interestingly, patients with CVD have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality from infections. In a nationwide population cohort study in Taiwan, patients with heart failure (HF) were twice as likely to develop herpes zoster and had significantly lower event-free survival compared with patients without HF.Citation10 Similarly, HF and COPD have been identified as independent prognostic factors for influenza-associated hospitalization and mortality.Citation11 Patients with HF have a higher 30-day mortality rate when hospitalized for pneumonia.Citation13 In a retrospective analysis of the National Inpatient Sample database, influenza in patients with HF increased the duration of hospitalization and in-hospital morbidity and mortality.Citation12

CRDs

CRDs are one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, responsible for 3.9 million deaths in 2017 ().Citation4 More than 90% of COPD-related deaths occur in LMICs.Citation4,Citation18,Citation48 In India, CRDs were responsible for >830,000 deaths in 2017 and they were the fourth leading condition accounting for the most disability-adjusted life-years.Citation5

Exacerbations (acute worsening of respiratory symptoms) are one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in patients with CRDs.Citation19,Citation49,Citation50 In a long-term follow-up of >73,000 patients hospitalized for COPD in Canada, health status declined following severe exacerbations, and risk of successive severe exacerbations increased with each event.Citation49,Citation50 In a case-series analysis of data from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), acute COPD exacerbations were associated with a 65% and 51% increased risk of MI and stroke, respectively, within 91 days of onset.Citation51 Asthma exacerbations have been shown to accelerate decline in lung function and significantly increase the risk of MI and stroke.Citation52,Citation53

VPDs contribute significantly to infection-induced exacerbations in adults with CRDs.Citation19 Viruses have been detected in 60–80% and 22–64% of adults with asthma and COPD exacerbations, respectively.Citation54,Citation55 Viral infections are associated with increased duration of hospitalization, deterioration of lung function and worse hypoxemia in patients with COPD exacerbations.Citation56 Influenza causes excess morbidity and mortality in patients with COPD.Citation20 Older adults and those with NCDs are at higher risk of complications associated with influenza infection, including pneumonia and respiratory failure, and admittance to an intensive care unit (ICU).Citation57 During the 2009 influenza pandemic, hospital-based surveillance data across Central America and the Dominican Republic showed that 61% of patients who died had pre-existing chronic diseases, including asthma (11%) and COPD (5%).Citation58 In the UK, COPD and asthma were reported in 20% and 19% of influenza-infected patients, respectively,Citation59 and in Spain COPD was significantly associated with worse outcomes in patients infected with influenza (OR: 1.51 [95% CI: 1.03–2.2]; p = .002).Citation60

There are several proposed mechanisms by which infections may contribute to the pathogenesis and prognosis of CRDs. However, contribution to overall disease burden is not fully understood. Infections have been shown to increase inflammation in the airways and reduce expiratory flow, resulting in dyspnea and exacerbations.Citation50 Respiratory viral infections have been implicated in the desquamation of epithelial cells, microvascular dilation, edema and infiltration of inflammatory cells, such as CD8 T-lymphocytes, into the airway. This results in reduced muco-ciliary clearance and decreased bacterial removal via macrophages, thus increasing susceptibility to bacterial infection.Citation20,Citation61–63

Diabetes and chronic kidney disease

In 2017, diabetes resulted in 1.4 million deaths worldwide, an increase of 15.1% for type 1 and 43.0% for type 2 since 2007 ().Citation4 Diabetes is a leading cause of disability worldwide.Citation6 In India in 2017, 68 million people had diabetes, a >2-fold increase from the 26 million in 1990, and there were 228,000 deaths, accounting for 2.4% of total deaths.Citation5,Citation6,Citation64 The incidence and burden of diabetes are predicted to rise in future years.Citation6 Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was responsible for 1.2 million deaths worldwide in 2017, a 33.7% rise in mortality since 2007.Citation4,Citation7 In India, CKD was responsible for >220,000 deaths in 2017.Citation7

The unfavorable relationship between infections and disease pathology is also true for CKD and diabetes. Patients with diabetes and CKD have an increased risk of infection due to impaired immunity and possible disease complications ().Citation16

In a retrospective analysis of individual-participant data by the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, diabetes significantly increased the risk of premature death from any cause (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.80 [95% CI: 1.71–1.90]), including pneumonia and other infectious diseases.Citation22 Similarly, CKD has been implicated as a risk factor for all-cause mortality and CVD.Citation65 In a systematic review and meta-analysis of >610,000 participants, diabetes was associated with higher hospital admissions for seasonal influenza (OR: 9.91 [95% CI: 5.46–17.99]). Pandemic influenza was associated with higher risk of death in patients with diabetes.Citation17 Similarly, relative risk of hepatitis B infection was 43% higher in those with diabetes compared with those without diabetes in a retrospective study in China.Citation21

Vaccination in patients with NCDs

The risk of infections and severity of associated outcomes are significantly increased in patients with NCDs.Citation8-15 Vaccination is an effective preventative public health strategy and there are various vaccines available for adults, especially those with NCDs ().Citation66-88 Its increased utilization has the potential to reduce the incidence and socioeconomic burden of VPDs in all adults (particularly those with NCDs), and to substantially contribute to a healthier older population. Despite immunosenescence, protective immune responses are still observed in older adults, reducing serious disease and associated complications. Furthermore, the development of vaccine adjuvants and implementation of booster programs have been shown to improve immune responses in this population.Citation89,Citation90 Despite these benefits, vaccination strategies in adults, particularly in LMICs, have not been widely implemented, and there is a need for a new approach to expand vaccination programs.Citation89

Table 2. Recommendations for vaccinations in adults with key chronic diseases provided by various guidelines across the world.Citation66-88

Aging is a known risk factor for most NCDs and can increase susceptibility to infectious diseases and VPDs.Citation91 Furthermore, infections can induce inflammation, which in turn may accelerate aging.Citation92,Citation93 The World Health Organization (WHO) created the concept of ‘healthy aging’–developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older-age”–as a response to the worldwide challenges associated with an increasing aging population.Citation94 The strategy hopes to improve adult vaccination access worldwide, which may help to defer some of the negative effects of aging.Citation89

There is a wealth of evidence that demonstrates the benefits of vaccines in patients with NCDs, such as the following examples assessing the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in patients with a range of NCDs.

In a systematic review of >12,000 patients who received influenza vaccines or placebo/no-treatment (1991–2009), cardiovascular mortality was significantly reduced in vaccinated patients (relative risk [RR]: .45 [95% CI: .26–.76]; p = .003).Citation95 The influenza vaccination has also been shown to decrease the risk of stroke by ~20% (OR: .82 [95% CI: .75–.91]; p < .001); this effect was consistent across all subgroups, indicating that vaccination may be beneficial in reducing the risk of stroke even in low-risk populations.Citation96 Similarly, in a population-based study of >27,000 patients aged ≥60 years in Spain, pneumococcal vaccination was associated with a 35% (95% CI: .01–.58) reduction in the adjusted risk of ischemic stroke.Citation97 In a large meta-analysis of >230,000 patients, pneumococcal vaccination was associated with significant reduction in the risk of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) events in patients aged ≥65 years (OR: .83 [95% CI: .71–.97]).Citation98

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of >82,000 patients with HF (1990–2013),Citation99-106 all-cause mortality risk was reduced by ~30% in patients vaccinated against influenza (HR: .69 [95% CI: .51–.87).Citation107 In a case-control study (1997–1998), influenza vaccines had a protective effect in patients with known coronary heart disease (CHD), resulting in a 67% reduction in the risk of MI during the subsequent influenza season (OR: .33 [95% CI: .13–.82; p = .017]).Citation43,Citation108

In patients with COPD, influenza vaccination significantly reduced the incidence of acute exacerbations and respiratory illness (RR: .33; p = .005) in a prospective trial in India; the overall effectiveness of influenza vaccines was 67% in patients with COPD.Citation109 Yearly influenza vaccinations in Taiwan reduced the risk of hospitalization for ACS by 54% (HR: .46 [95% CI: .39–.55]; p < .001) and the risk of developing lung cancer by 60% (HR: .40 [95% CI: .35–.45]; p < .001) in patients with COPD aged ≥55 years.Citation110,Citation111 The benefit was more pronounced in those receiving ≥4 vaccinations.

In patients with diabetes, seasonal influenza vaccination was associated with a significantly reduced risk of all-cause mortality, particularly among those aged ≥65 years.Citation112 In a retrospective cohort study of data from the UK CPRD, influenza vaccination was associated with significantly fewer hospital admissions for stroke (IRR: .70 [95% CI: .53–.91]), HF (IRR: .78 [95% CI: .65–.92]), and pneumonia or influenza (IRR: .85 [95% CI: .74–.99]) and all-cause death (IRR: .76 [95% CI: .65–.83]) among diabetic patients.Citation113 In a multivariate analysis combining data from four influenza seasons (2002–2005), vaccination was associated with a 33% reduction in all-cause mortality among adults aged ≥65 years with diabetes (OR: .67 [95% CI: .47–.96]).Citation114 In a retrospective study including >9,000 elderly patients with diabetes, those vaccinated against influenza had lower rates of pneumonia and respiratory failure and were less likely to be admitted to ICU (adjusted HR: .30 [95% CI: .19–.47]).Citation115 In patients with CKD aged ≥55 years in Japan, influenza vaccination reduced the risk of hospitalization for HF by 69% (HR: .31 [95% CI: .26–.39]; p < .001) and ACS by 65% (HR: .35 [95% CI: .30–.42]; p < .001).Citation116,Citation117

The health benefits provided by these vaccines are not only limited to reducing VPDs and related complications in adults with NCDs, but may extend further in minimizing the risk of developing certain chronic diseases. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2005–2010), conducted in the United States, showed that hepatitis B vaccination was associated with a reduced risk of developing diabetes (OR: .67 [95% CI: .52–.84]).Citation118 Similarly, the Bacillus Calmette Guérin (BCG) vaccination reduced hemoglobin A1c to near-normal levels in patients with type 1 diabetes.Citation119 Both the BCG and hepatitis B vaccines are routinely administered to infants through the National Immunization Program in India.Citation120 An expanded recommendation in high-risk adults to prevent/alleviate diabetes is not currently in place, but is an interesting point for future clinical trials.

Challenges

In 2003, the WHO urged member states to “establish and implement strategies to increase vaccination coverage of all people at high risk, including the elderly and persons with underlying diseases, with the goal of attaining vaccination coverage of the elderly population of at least 75% by 2010”.Citation75 However, these goals are far from being achieved. Analysis of influenza vaccination uptake in the US and England shows that coverage consistently falls short of these targets.Citation82, Citation83 Various recommendations are in place for vaccinations in patients with NCDs; however, they vary across countries and some are incomplete ().Citation4,Citation66,Citation69-78 Despite the growing burden of NCDs in India, the Indian National Immunization Program does not include any specific recommendations for the vaccination of adults with NCDs. Some medical societies, such as the Indian Medical Association, have published vaccination guidelines that include recommendations for adults. However, these guidelines are convoluted by various risk factors and lack clear guidance for adults with NCDs. In addition, there is a need for continuity between different medical guidelines.Citation88,Citation121–126 Due to the lack of national guidelines there is negligible financial support available, leaving the cost of adult vaccinations solely to the individual. This acts as a major barrier to vaccination uptake.Citation121

Several other barriers exist that impact the coverage of adult vaccinations, including those related to access, affordability, reimbursement and infrastructure.Citation127 The impact of these barriers varies between countries; however, inadequate vaccination coverage is a worldwide problem, even in countries where recommendations, infrastructure and funding are in place to fully support adult vaccination programs.Citation127 Therefore, some of the most important challenges are those related to psychologic and educational factors.Citation128 Surveys have shown that many people are hesitant to receive vaccinations, due to a lack of awareness regarding impact of the underlying disease, and possible effectiveness of the vaccine itself. The perception of potential side effects associated with vaccinations is also a predominant barrier to vaccine uptake despite evidence demonstrating they are well tolerated and effective.Citation127–130 In addition, there is a common misperception that vaccinations are only relevant for children and are not a health priority for adults.Citation128,Citation131

In India, additional barriers prevent effective vaccination uptake. Lack of awareness and hesitancy among healthcare professionals (HCPs) and the public, as well as inadequate HCP recommendations, are major barriers to vaccination in adults with NCDs.Citation121,Citation132,Citation133 In a 2017 study, ~68% of the Indian population were unaware that adult vaccinations existed and believed that they were not necessary as they “felt healthy”.Citation134 In addition, NCD surveillance in India is insufficient, with reported inconsistencies and lack of standardization, which impede progress in understanding, preventing and treating these diseases.Citation135 Religious/cultural beliefs, particularly in rural India, may also prevent effective vaccination uptake.Citation36,Citation121,Citation132,Citation133 Compared with high-income countries, India is under tighter economic constraints, so it is of high importance that effective programs are implemented, as vaccinations are one of the most cost-effective healthcare measures available.Citation136

Solutions

Multidisciplinary recommendations by medical societies, including the Indian Medical Association, to prioritize adult vaccinations may have an impact on future programs; however, standardization of these recommendations is essential. The implementation of national guidelines for adults with NCDs is desirable; however, this would require multidisciplinary coordination and leadership among HCPs and policymakers to promote these guidelines and change the perceived need in this population.Citation121,Citation137 Raising awareness and educating HCPs and the public on the importance and benefits of adult vaccinations, particularly among those with NCDs, may help increase uptake and compliance, and ultimately reduce the burden of VPDs on the healthcare system in India.Citation121,Citation137 As patients with NCDs usually require regular medical visits, this provides an opportunity for HCPs to highlight the recommended vaccines and alleviate concerns over potential side effects to these patients in a one-to-one discussion.Citation121 The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent roll-out of the largest vaccination program in India represents a challenge but also an opportunity for implementing a more robust adult vaccination program.

In the US, the 4 PillarsTM Program was developed to provide a step-by-step guide to improve adult vaccination rates. This program focuses on convenient vaccination services, communication with patients about the importance of vaccination and the availability of vaccines, enhanced office systems to facilitate vaccination and motivation through an office champion.Citation138,Citation139 Implementation of the 4 PillarsTM Program was associated with a significant increase in vaccinations among high-risk groups, including those with chronic diseases, compared with non-high-risk groups (e.g. influenza vaccination increased in patients with chronic lung disease [OR = 1.14] and diabetes [OR = 1.14]).Citation139

Some of the key proposals that may help to increase vaccination coverage in adult patients, including those with NCDs, in India include:Citation121,Citation128,Citation138–140

Improving awareness and education of HCPs and patients

Educate on the direct and indirect benefits of adult vaccination that extend beyond disease prevention, such as improving quality of life, enabling independent living in the elderly, improving life expectancy, and reducing financial burden

Alleviate concerns about vaccine efficacy by changing the narrative to discuss the reduction in risk of disease instead of efficacy rates

Address the perception that vaccines are only for children

Promoting the concept of healthy aging and highlighting the importance of life-course vaccination for continued life-long healthcare

Implementing and distributing national adult vaccination guidelines and ensuring clear steps and paths of action are provided

Ensuring there are mechanisms for feedback to monitor desired outcomes

Involving religious leaders in education activities within the community

Conclusion

Vaccinations are one of the most cost-effective and efficient healthcare interventions for reducing the incidence and burden of VPDs, not only in children but also in adults, especially those with NCDs. However, utilization rates across the world are inadequate. This leaves adults, particularly those with NCDs, vulnerable to VPDs and their associated complications. There are numerous health and economic benefits of vaccinating adult patients with NCDs, and there should be a global focus on increasing vaccination coverage in this population and among adults in general. It is extremely important to increase awareness and education of HCPs and the public on the widespread benefits of vaccinations and ensure that vaccination programs are adequately implemented and accessible to all. In India, the lack of guidance, growing burden of NCDs and additional barriers to vaccine uptake highlight the need for action. With India implementing one of the world’s largest COVID-19 vaccination programs, now is the time to improve the awareness and accessibility of their adult vaccination programs for all VPDs, particularly among those with NCDs.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank MediTech Media for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination, on behalf of GSK Vaccines. Zoe Cornhill provided medical writing support and Danielle Lindley coordinated manuscript development and editorial support.

Disclosure statement

AV declares no conflicts of interest. ADP was previously employed and previously had stock ownership in the GSK Group of Companies. SK, AA and SA are employed by the GSK Group of Companies. SK has stock ownership in the GSK Group of Companies.

Additional information

Funding

References

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. About chronic diseases. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm .

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases: Country profiles 2018; 2018. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.who.int/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases#tab=tab_1 .

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases - Fact sheet. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases .

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1736–13. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7.

- Menon GR, Singh L, Sharma P, Yadav P, Sharma S, Kalaskar S, Singh H, Adinarayanan S, Joshua V, Kulothungan V, et al. National burden estimates of healthy life lost in India, 2017: an analysis using direct mortality data and indirect disability data. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(12):e1675–84. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30451-6.

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7.

- GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):709–33. PMC7049905. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30045-3.

- World Health Organization. Global health and aging; 2011. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health.pdf?ua=1 .

- Corrales-Medina VF, Alvarez KN, Weissfeld LA, Angus DC, Chirinos JA, Chang CCH, Newman A, Loehr L, Folsom AR, Elkind MS, et al. Association between hospitalization for pneumonia and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2015;313(3):264–74. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.18229.

- Wu PH, Lin YT, Lin CY, Huang MY, Chang WC, Chang WP. A nationwide population-based cohort study to identify the correlation between heart failure and the subsequent risk of herpes zoster. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):17. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-0747-9.

- Hak E, Verheij TJM, van Essen GA, Lafeber AB, Grobbee DE, Hoes AW. Prognostic factors for influenza-associated hospitalisation and death during an epidemic. Epidemiol Infect. 2001;126(2):261–68. doi:10.1017/S0950268801005180.

- Panhwar MS, Kalra A, Gupta T, Kolte D, Khera S, Bhatt DL, Ginwalla M. Effect of influenza on outcomes in patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7(2):112–17. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2018.10.011.

- Thomsen RW, Kasatpibal N, Riis A, Norgaard M, Sorensen HT. The impact of pre-existing heart failure on pneumonia prognosis: population-based cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1407–13. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0672-3.

- Barnes M, Heywood AE, Mahimbo AR, Rahman B, Newall AT, Macintyre CR. Acute myocardial infarction and influenza: a meta-analysis of case–control studies. Heart. 2015;101(21):1739–47. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307691.

- Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJH, Hubbard R, Farrington P, Vallance P, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(25):2611–18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041747.

- Toniolo A, Cassani G, Puggioni A, Rossi A, Colombo A, Onodera T, Ferrannini E. The diabetes pandemic and associated infections: suggestions for clinical microbiology. Rev Med Microbiol. 2019;30(1):1–17. doi:10.1097/MRM.0000000000000155.

- Mertz D, Kim TH, Johnstone J, Lam PP, Science M, Kuster SP, Fadel SA, Tran D, Fernandez E, Bhatnagar N, et al. Populations at risk for severe or complicated influenza illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5061. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5061.

- Abubakar I, Tillmann T, Banerjee A. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385(9963):117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2.

- Hewitt R, Farne H, Ritchie A, Luke E, Johnston SL, Mallia P. The role of viral infections in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016;10(2):158–74. doi:10.1177/1753465815618113.

- Frickmann H, Jungblut S, Hirche TO, Gross U, Kuhns M, Zautner AE. The influence of virus infections on the course of COPD. Eur J Microbiol Immunol. 2012;2(3):176–85. doi:10.1556/EuJMI.2.2012.3.2.

- Zhang X, Zhu X, Ji Y, Li H, Hou F, Xiao C, Yuan P. Increased risk of hepatitis B virus infection amongst individuals with diabetes mellitus. Biosci Rep. 2019;39(3):BSR20181715. doi:10.1042/BSR20181715.

- Seshasai SRK, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, Angelantonio ED, Gao P, Sarwar N, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):829–41. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1008862.

- Syed-Ahmed M, Narayana M. Immune dysfunction and risk of infection in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019;26(1):8–15. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2019.01.004.

- Casqueiro J, Casqueiro J, Alves C. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus: a review of pathogenesis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(Suppl 1):S27–36. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.94253.

- World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd_report_full_en.pdf .

- Ritchie H, Roser M. Age structure; 2019. [accessed 2021 July]. https://ourworldindata.org/age-structure .

- He W, Goodkind D, Kowal P. An aging world: 2015 - International population reports. Washington (DC); 2016. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p95-16-1.pdf .

- World Health Organization. Ageing and health; 2018. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health .

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 and the decade of healthy ageing; 2020. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/decade-of-healthy-ageing/decade-connection-series---covid-19-en.pdf?sfvrsn=d3f887b0_7 .

- Clarfield A, Jotkowitz A. Age, ageing, ageism and “age-itation” in the age of COVID-19: rights and obligations relating to older persons in Israel as observed through the lens of medical ethics. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2020;9(1):64. doi:10.1186/s13584-020-00416-y.

- Torres A, Blasi F, Dartois N, Akova M. Which individuals are at increased risk of pneumococcal disease and why? Impact of COPD, asthma, smoking, diabetes, and/or chronic heart disease on community-acquired pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease. Thorax. 2015;70(10):984–89. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206780.

- Zwaans WAE, Mallia PW. The relevance of respiratory viral infections in the exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - a systematic review. J Clin Virol. 2014;61(2):181–88. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2014.06.025.

- Salam N, Rane S, Das R, Faulkner M, Gund R, Kandpal U, Lewis V, Mattoo H, Prabhu S, Ranganathan V, et al. T cell ageing: effects of age on development, survival & function. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138(5):595–608.

- Pothineni NVK, Subramany S, Kuriakose K, Shirazi LF, Romeo F, Shah PK, Mehta JL. Infections, atherosclerosis, and coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(43):3195–201. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx362.

- Ishigami J, Matsushita K. Clinical epidemiology of infectious disease among patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2019;23(4):437–47. doi:10.1007/s10157-018-1641-8.

- Arokiasamy P. India’s escalating burden of non-communicable diseases. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(12):E1262. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30448-0.

- Sinha R, Pati S. Addressing the escalating burden of chronic diseases in India: Need for strenthening primary care. J Family Med Prim Care. 2017;6(4):701–08. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1_17.

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases: country profiles 2018. 2018. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-profiles-2018/en/ .

- Mahal A, Karan A, Engelgau M The economic implications of non-communicable disease for India. HNP discussion paper. Washington (DC): The World Bank; 2010. [accessed 2022 February]. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/13649 .

- Verma R, Khanna P, Chawla S. Adult immunization in India: Importance and recommendations. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(9):2180–82. doi:10.4161/hv.29342.

- Ministry of Home Affairs. Report on medical certification of cause of death 2017. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-Documents/mccd_Report1/MCCD_Report-2017.pdf .

- Emsley HCA, Tyrrell PJ. Inflammation and infection in clinical stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22(12):1399–419. doi:10.1097/01.WCB.0000037880.62590.28.

- Madjid M, Aboshady I, Awan I, Litovsky S, Casscekks SW. Influenza and cardiovascular disease: is there a casual relationship? Tex Heart Inst J. 2004;31(1):4–13.

- Nagel MA, Gilden D. The relationship between herpes zoster and stroke. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015;15(4):16. doi:10.1007/s11910-015-0534-4.

- Tadic M, Cuspidi C, Grassi G. Heart rate as a predictor of cardiovascular risk. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48(3):e12892. doi:10.1111/eci.12892.

- Wu PH, Chuang YS, Lin YT. Does herpes zoster increase the risk of stroke and myocardial infarction? A comprehensive review. J Clin Med. 2019;8(4):547. doi:10.3390/jcm8040547.

- Nguyen JL, Yang W, Ito K, Matte TD, Shaman J, Kinney PL. Seasonal influenza infections and cardiovascular disease mortality. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;1(3):274–81. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0433.

- World Health Organization. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); 2017. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd)

- Suissa S, Dell’Aniello S, Ernst P. Long-Term natural histroy of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax. 2012;67(11):957–63. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201518.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; 2020. [accessed 2021 July]. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/GOLD-2020-FINAL-ver1.2-03Dec19_WMV.pdf .

- Rothnie KJ, Connell O, Mullerova H, Smeeth L, Pearce N, Douglas I, Quint JK. Myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke after exacerbations of chronic obstrutcive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(8):935–46. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201710-815OC .

- O’Byrne PM, Pedersen S, Lamm CJ, Tan WC, Busse W. Severe exacerbations and decline in lung function in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(1):19–24. doi:10.1164/rccm.200807-1126OC .

- Raita Y, Camargo CA, Faridi MK, Brown DFM, Shimada YJ, Hasegawa K. Risk of acute myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke in patients with asthma exacerbation: a population-based, self-controlled case series study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(1):188–94. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.06.043.

- Grissell TV, Powell H, Shafren DR, Boyle MJ, Hensley MJ, Jones PD, Whitehead BF, Gibson PG. Interleukin-10 gene expression in acute virus-induced asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(4):433–39. doi:10.1164/rccm.200412-1621OC.

- Wark PAB, Tooze M, Powell H, Parsons K. Viral and bacterial infection in acute asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease increases the risk of readmission. Respirology. 2013;18(6):996–1002. doi:10.1111/resp.12099.

- Ko FW, Chan KP, Hui DS, Goddard JR, Shaw JG, Reid DW, Yang IA. Acute exacerbation of COPD. Respirology. 2016;21(7):1152–65. doi:10.1111/resp.12780.

- Loubet P, Samih-Lenzi N, Galtier F, Vanhems P, Loulergue P, Duval X, Jouneau S, Postil D, Rogez S, Valette M, et al. Factors associated with poor outcomes among adults hospitalizaed for influenza in France: a three-year prospective multicenter study. J Clin Virol. 2016;79:68–73. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2016.04.005.

- Chacon R, Mirza S, Rodriguez D, Paredes A, Guzman G, Moreno L, Then CJ, Jara J, Blanco N, Bonilla L, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of deaths associated with influenza A(H1N1) pdm09 in Central America and Dominican Republic 2009–2010. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):734. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2064-z.

- Pebody RG, McLean E, Zhao H, Cleary P, Bracebridge S, Foster K, Charlett A, Hardelid P, Waight P, Ellis J, et al. Pandemic influenza a (H1N1) 2009 and mortality in the United Kingdom: risk factors for death, April 2009 to March 2010. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(20):19571. doi:10.2807/ese.15.20.19571-en.

- Santa-Olalla Peralta P, Cortes-Garcia M, Vicente-Herrero M, Castrillo-Villamandos C, Arias-Bohigas P, Pachon-Del Amo I, Sierra-Moros MJ. Risk factors for disease severity among hospitalised patients with 2009 pandemic influenza a (H1N1) in Spain, April – December 2009. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(38):19667. doi:10.2807/ese.15.38.19667-en.

- Yamada K, Elliott WM, Hayashi S, Brattsand R, Roberts C, Vitalis TZ, Hogg JC. Latent adenoviral infection modifies the steroid response in allergic lung inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106(5):844–51. doi:10.1067/mai.2000.110473.

- Hogg JC. Role of latent viral infections in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(Suppl 2):S71–S5. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.164.supplement_2.2106063.

- De Serres G, Lampron N, La Forge J, Rouleau I, Bourbeau J, Weiss K, Barret B, Boivin G. Importance of viral and bacterial infections in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. J Clin Virol. 2009;46(2):129–33. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2009.07.010.

- India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Diabetes Collaborators. The increasing burden of diabetes and variations among the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(12):e1352–62. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30387-5.

- Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Amin MG, Stark PC, MacLeod B, Griffith JL, et al. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a pooled analysis of community-based studies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(5):1307–15. doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000123691.46138.E2.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart disease, stroke, or other cardiovascular disease and adult vaccination; 2016. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/rec-vac/health-conditions/heart-disease.html .

- Wang Y, Cheng M, Wang S, Wu F, Yan Q, Yang Q, Li Y, Guo X, Fu C, Shi Y, et al. Vaccination coverage with the pneumococcal and influenza vaccine among persons with chronic diseases in Shanghai, China, 2017. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):359. PMC7081528. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-8388-3.

- 23-valentpneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2008;83( 42):373–84.

- NHS England. Directed enhanced service specification. Seasonal influenza and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination programme 2019/20; 2019. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/dess-sfl-and-pneumococcal-1920.pdf .

- Davis MM, Taubert K, Benin AL, Brown DW, Mensah GA, Baddour LM, Dunbar S, Krumholz HM. Influenza vaccination as secondary prevention for cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(7):1498–502. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.004.

- Piepoli M, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney M-T, Corrà U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315–81. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106.

- World Health Organization. Recommendations on influenza vaccination during the 2019–2020 winter season; 2019. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/413270/Influenza-vaccine-recommendations-2019-2020_en.pdf .

- Gabutti G, Bolognesi N, Sandri F, Florescu C, Stefanati A. Varicella zoster virus vaccines: an update. Immunotargets Ther. 2019;8:15–28. doi:10.2147/ITT.S176383.

- Klaric JS, Beltran TA, McClenathan BM. An association between herpes zoster vaccination and stroke reduction among elderly individuals. Mil Med. 2019;184(Suppl 1):126–32. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy343.

- World Health Organization. Prevention and control of influenza pandemics and annual epidemics; 2003. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/1_WHA56_19_Prevention_and_control_of_influenza_pandemics.pdf .

- World Health Organization. Summary of WHO position papers - Recommendations for routine immunization; 2020. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.who.int/immunization/policy/Immunization_routine_table1.pdf .

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Renal disease and adult vaccination. Washington (DC): Office of the Associate Director for Communication, Digital Media Branch, Division of Public Affairs; 2016. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/rec-vac/health-conditions/renal-disease.html .

- Public Health England. Complete routine immunisation; 2020. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-complete-routine-immunisation-schedule .

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccinations for adults with lung disease; 2016. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/rec-vac/health-conditions/lung-disease.html .

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Herpes zoster vaccination; 2015. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/shingles/hcp/zostavax/hcp-vax-recs.html#:~:text=CDC%20recommends%20a%20single%20dose,precaution%20exists%20for%20their%20condition .

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumocococcal vaccination: Summary of who and when to vaccinate; 2019. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/who-when-to-vaccinate.html .

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimates of influenza vaccination coverage among adults - United States, 2017-18 Flu season; 2018. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1718estimates.htm .

- Public Health England. Seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in GP patients: winter season 2018 to 2019; 2019. [accessed 2021 July]. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/804889/Seasonal_influenza_vaccine_uptake_in_GP_patients_1819.pdf .

- NHS. Who should have the pneumococcal vaccine; 2019. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/when-is-pneumococcal-vaccine-needed/#:~:text=Adults%20aged%2065%20or%20over,serious%20forms%20of%20pneumococcal%20infection .

- NHS. Flu vaccine; 2020. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/flu-influenza-vaccine/ .

- NHS. Who can have the shingles vaccine? [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/who-can-have-the-shingles-vaccine/ .

- NHS. Hepatitis B vaccine overview; 2018. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/hepatitis-b-vaccine/ .

- Wankhedkar R, Tandon RN, Monga VK. Indian medical association: Life course immunization guidebook: a quick reference guide; 2018. [accessed 2021 July]. http://www.ima-india.org/ima/pdfdata/IMA_LifeCourse_Immunization_Guide_2018_DEC21.pdf .

- Aguado MT, Barratt J, Beard JR, Blomberg BB, Chen WH, Hickling J, Hyde TB, Jit M, Jones R, Poland GA, et al. Report on WHO meeting on immunization in older adults: Geneva, Switzerland, 22–23 March 2017. Vaccine. 2018;36(7):921–31. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.029 .

- Michel JP, Gusmano M, Blank PR, Philp I. Vaccination and healthy ageing: How to make life-course vaccination a successful public health strategy. Eur Geriatr Med. 2010;1(3):155–65. doi:10.1016/j.eurger.2010.03.013.

- Gardner ID. The effect of aging on susceptibility to infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1980;2(5):801–10. doi:10.1093/clinids/2.5.801.

- Kennedy BK, Berger SL, Brunet A, Campisi J, Cuervo AM, Epel ES, Franceschi C, Lithgow GJ, Morimoto RI, Pessin JE, et al. Aging: a common driver of chronic diseases and a target for novel interventions. Cell. 2014;159(4):709–13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.039.

- Bektas A, Schurman SH, Sen R, Ferrucci L. Aging, inflammation and the environment. Exp Gerontol. 2018;105:10–18. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2017.12.015.

- World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health; 2015. [accessed 2021 July]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf;jsessionid=8203501201A6360D0E1D3273FC0618AA?sequence=1 .

- Clar C, Oseni Z, Flowers N, Keshtkar-Jahromi M, Rees K. Influenza vaccines for preventing cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;5(5):CD005050. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005050.pub3.

- Lee KR, Bae JH, Hwang IC, Kim KK, Suh HS, Ko KD. Effect of influenza vaccination on risk of stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2017;48(3–4):103–10. doi:10.1159/000478017.

- Vila-Corcoles A, Ochoa-Gondar O, Rodriguez-Blanco T, Gutierrez-Perez A, Vila-Rovira A, Gomez F, Raga X, de Diego C, Satue E, Salsench E, et al. Clinical effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination against acute myocardial infarction and stroke in people over 60 years: the CAPAMIS study, one-year follow-up. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):222. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-222.

- Ren S, Newby D, Li SC, Walkom E, Miller P, Hure A, Attia J. Effect of the adult pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine on cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart. 2015;2(1):e000247. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2015-000247.

- Kopel E, Klempfner R, Goldenberg I. Influenza vaccine and survival in acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16(3):264–70. doi:10.1002/ejhf.14.

- Wu W-C, Jiang L, Friedmann PD, Trivedi A. Association between process quality measures for heart failure and mortality among US veterans. Am Heart J. 2014;168(5):713–20. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2014.06.024.

- Vardeny O, Claggett B, Udell JA, Packer M, Zile M, Rouleau J, Swedberg K, Desai AS, Lefkowitz M, Shi V, et al. Influenza vaccination in patients with chronic heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4(2):152–58. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2015.10.012.

- Liu IF, Huang CC, Chan WL, Huang PH, Chung CM, Lin SJ, Chen J-W, Leu H-B. Effects of annual influenza vaccination on mortality and hospitalization in elderly patients with ischemic heart disease: a nationwide population-based study. Prev Med. 2012;54(6):431–33. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.03.020.

- Kaya H, Beton O, Acar G, Temizhan A, Cavusoğlu Y, Guray U, Zoghi M, Ural D, Ekmekci A, Gungor H, et al. Influence of influenza vaccination on recurrent hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Herz. 2017;42(3):307–15. doi:10.1007/s00059-016-4460-2.

- Vila-Córcoles A, Ochoa O, de Diego C, Valdivieso A, Herreros I, Bobé F, Alvarez M, Juárez M, Guinea I, Ansa X, et al. Effects of annual influenza vaccination on winter mortality in elderly people with chronic pulmonary disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(1):10–17. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01414.x.

- Blaya-Nováková V, Prado-Galbarro FJ, Sarría-Santamera A. Effects of annual influenza vaccination on mortality in patients with heart failure. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(5):890–92. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckw141.

- Mohseni H, Kiran A, Khorshidi R, Rahimi K. Influenza vaccination and risk of hospitalization in patients with heart failure: a self-controlled case series study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(5):326–33. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw411.

- Poudel S, Shehadeh F, Zacharioudakis IM, Tansarli GS, Zervou FN, Kalligeros M, van Aalst R, Chit A, Mylonakis E. The effect of influenza vaccination on mortality and risk of hospitalization in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(4):ofz159. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz159.

- Naghavi M, Barlas Z, Siadaty S, Naguib S, Madjid M, Casscells W. Association of influenza vaccination and reduced risk of recurrent myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;102(25):3039–45. doi:10.1161/01.cir.102.25.3039.

- Menon B, Gurnani M, Aggarwal B. Comparison of outpatient visits and hospitalisations, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, before and after influenza vaccination. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(4):593–98. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01641.x.

- Chen KY, Wu SM, Liu JC, Lee KY. Effect of annual influenza vaccination on reducing lung cancer in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from a population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(47):e18035. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000018035.

- Sung LC, Chen CI, Fang YA, Lai CH, Hsu YP, Cheng TH, Miser JS, Liu J-C. Influenza vaccination reduces hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based cohort study. Vaccine. 2014;32(30):3843–49. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.064.

- Santos G, Tahrat H, Bekkat-Berkani R. Immunogenicity, safety, and effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(8):1853–66. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1446719.

- Vamos EP, Pape UJ, Curcin V, Harris MJ, Valabhji J, Majeed A, Millett C. Effectiveness of the influenza vaccine in preventing admission to hospital and death in people with type 2 diabetes. CMAJ. 2016;188(14):E342–E51. doi:10.1503/cmaj.151059.

- Rodriguez-Blanco T, Vila-Corcoles A, de Diego C, Ochoa-Gondar O, Valdivieso E, Bobe F, Morro A, Herńndez N, Martin A, Calamote F, et al. Relationship between annual influenza vaccination and winter mortality in diabetic people over 65 years. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8(3):363–70. doi:10.4161/hv.18548.

- Wang I, Lin C, Chang Y, Lin P, Liang C, Liu Y, Chang C-T, Yen T-H, Huang C-C, Sung F-C, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccination in elderly diabetic patients: a retrospective cohort study. Vaccine. 2013;31(4):718–24. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.11.017.

- Fang YA, Chen CI, Liu JC, Sung LC. Influenza vaccination reduces hospitalization for heart failure in elderly patients with chronic kidney disease: a population-based cohort study. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2016;32(3):290–98. doi:10.6515/acs20150424l.

- Chen CI, Kao PF, Wu MY, Fang YA, Miser JS, Liu JC, Sung L-C. Influenza vaccination is associated with lower risk of acute coronary syndrome in elderly patients with chronic kidney disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(5):e2588. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002588.

- Huang J, Ou HY, Lin J, Karnchanasorn R, Feng W, Samoa R, Chuang L-M, Chiu KC. The impact of hepatits B vaccination status on the risk of diabetes, implicating diabetes risk reduction by successful vaccination. PLOS One. 2015;10(10):e0139730. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139730.

- Kuhtreiber WM, Tran L, Kim T, Dybala M, Nguyen B, Plager S, Huang D, Janes S, Defusco A, Baum D, et al. Long-term reduction in hyperglycemia in advanced type 1 diabetes: the value of induced aerobic glycolysis with BCG vaccinations. NPJ Vaccines. 2018;3(1):23. doi:10.1038/s41541-018-0062-8.

- National Health Portal India. Universal Immunisation Programme. [accessed 2022 January]. https://www.nhp.gov.in/universal-immunisation-programme_pg .

- Dash R, Agrawal A, Nagvekar V, Lele J, Di Pasquale A, Kolhapure S, Parikh R. Towards adult vaccination in India: a narrative literature review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(4):991–1001. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1682842.

- Ramasubramanian V. Adult immunization in India; 2019. [accessed 2022 February]. https://apiindia.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/progress_in_medicine_2017/mu_06.pdf .

- Muruganathan A, Mathai D, Sharma SK. Adult immunization. New Delhi (India): The Association of Physicians of India Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2014.

- Guidelines for vaccination in normwal adults in India. Indian J Nephrol. 2016;26(Suppl 1):S7–S14.

- Federation of Obstetric & Gynaecological Societies of India. Good clinical practice recommendations on preconception; 2016. [accessed 2022 February]. https://www.fogsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/FOGSI-PCCR-Guideline-Booklet-Orange.pdf .

- Federation of Obstetric & Gynaecological Societies of India. Vaccination in women; 2015. [accessed 2022 February]. https://www.fogsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/vaccination_women.pdf .

- Smith LE, Webster RK, Weinman J, Amlôt R, Yiend J, Rubin J. Psychological factors associated with uptake of the childhood influenza vaccine and perception of post-vaccination side effects: a cross-sectional survey in England. Vaccine. 2017;35(15):1936–45. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.02.031.

- Doherty TM, Giudice GD, Maggi S. Adult vaccination as part of a healthy lifestyle: moving from medical intervention to health promotion. Ann Med. 2019;51(2):128–40. doi:10.1080/07853890.2019.1588470.

- Telford R, Rogers A. What influences elderly peoples’ decisions about whether to accept the influenza vaccination? a qualitative study. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(6):743–53. doi:10.1093/her/cyf059.

- Lytras T, Kopsachilis F, Mouratidou E, Papamichail D, Bonovas S. Interventions to increase seasonal influenza vaccine coverage in healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(3):671–81. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1106656.

- Sheikh S, Biundo E, Courcier S, Damm O, Launay O, Maes E, Marcos C, Matthews S, Meijer C, Poscia A, et al. A report on the status of vaccination in Europe. Vaccine. 2018;36(33):4979–92. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.06.044.

- Bagcchi S. India tackles vaccine preventable diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(6):637–38. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00009-2.

- John TJ, Dandona L, Sharma VP, Kakkar M. Continuing challenge of infectious diseases in India. Lancet. 2011;377(9761):252–69. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61265-2.

- TENNEWS.in. Majority of Indians are unaware of adult vaccinations; 2017. [accessed 2022 January]. https://tennews.in/majority-indians-unaware-adult-vaccinations/ .

- Nethan S, Sinha D, Mehrotra R. Non communicable disease risk factors and their trends in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18(7):2005–10. doi:10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.7.2005.

- Philip RK, Attwell K, Breuer T, Di Pasquale A, Lopalco PL. Life-course immunization as a gateway to health. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17(10):851–64. doi:10.1080/14760584.2018.1527690.

- Lahariya C, Bhardwaj P. Adult vaccination in India: status and the way forward. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(7):1508–10. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1692564.

- Lin CJ, Nowalk MP, Pavlik VN, Brown AE, Zhang S, Raviotta JM, Moehling KK, Hawk M, Ricci EM, Middleton DB, et al. Using the 4 pillars™ practice transformation program to increase adult influenza vaccination and reduce missed opportunities in a randomized cluster trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):623. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1940-1.

- Nowalk MP, Moehling KK, Zhang S, Raviotta JM, Zimmerman RK, Lin CJ. Using the 4 pillars to increase vaccination among high-risk adults: Who benefits? Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(11):651–55.

- World Health Organization SAGE Working group dealing with vaccine hesitancy. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy – a systematic review; 2014. [accessed 2022 January]. https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/3_SAGE_WG_Strategies_addressing_vaccine_hesitancy_2014.pdf.