ABSTRACT

Vaccine uptake rate is crucial for herd immunity. Medical care workers (MCWs) can serve as ambassadors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. This study aimed to assess MCWs’ willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, and to explore the factors affecting COVID-19 vaccination acceptance. A multicenter study among medical care workers was conducted in seven selected hospitals from seven geographical territories of China, and data were collected on sociodemographic characteristics, vaccine hesitancy, and health beliefs on COVID-19 vaccination among participants. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were performed to explore the correlations between individual factors and the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine. Among the 2681 subjects, 82.5% of the participants were willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccination. Multivariate regression analyses revealed that individuals with more cues to action about the vaccination, higher level of confidence about the vaccine, and higher level of trust in the recommendations of COVID-19 vaccine from the government and the healthcare system were more likely to get the COVID-19 vaccine. In contrast, subjects with higher level of perceived barriers and complacency were less likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccine. Overall, MCWs in China showed a high willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine. The governmental recommendation is an important driver and lead of vaccination. Relevant institutions could increase MCWs’ willingness to COVID-19 vaccines by increasing MCWs’ perception of confidence about COVID-19 vaccines and cues to action through various strategies and channels. Meanwhile, it can also provide evidence in similar circumstances in the future to develop vaccine promotion strategies.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused a significant impact on the world and becomes a pandemic of international concern.Citation1 It is obvious that rapid and high vaccine uptake levels among various population are the immediate urgency to curb the COVID-19 epidemic.Citation2 To develop herd immunity, it is estimated that at least 85% of the population have to be vaccinated given the current COVID-19 vaccine efficacy.Citation3,Citation4 Updated in March 2022, 27 of 339 vaccine candidates have been put into production, and China has reported that a total of 3.1 billion doses of the COVID-19 vaccine have been administered for free.Citation5,Citation6

Prevention and control of COVID-19 infection via vaccine programs depends not only on vaccine efficacy and safety, but also on vaccine acceptance among the general public.Citation3 Public’s vaccine acceptance is always influenced by many factors, and advice from medical professionals is often an important one, because medical care workers (MCWs) are an important source of information for vaccines and always serve as role models for the general population.Citation7,Citation8 Aside from the influence of healthcare providers vaccination behavior on others, the attitudes of healthcare providers toward vaccination have a powerful influence on the vaccination behavior of the public.Citation9 However, the actual level of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among MCWs remains unclear.

Vaccine hesitancy, a public health threat,Citation10,Citation11 has been regarded as one of the possible causes of declining vaccination coverage and increased outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.Citation12 Although MCWs are at higher risk of contracting COVID-19 and other infectious diseases than the general population, previous studies showed a widespread vaccine hesitancy among them, including the hesitancy against COVID-19 vaccination.Citation13,Citation14 In addition, some MCWs still reported continuous negative beliefs on vaccines, despite their decision to receive the vaccine.Citation15 Typically, some of them demonstrated their worries regarding its safety and long-lasting side effects, and some even occurred clinical levels of negative symptoms of emotions related to the COVID-19 vaccination.Citation13,Citation16 Therefore, vaccine hesitancy among MCWs can have widespread negative impact,Citation17–21 which can reduce their own vaccination rates and even affect vaccine acceptance in the general population.

It is full of meanings to investigate the rate of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, and to explore the relevant factors about the acceptance. Numerous studies showed the effectiveness of intervention targeting health belief model (HBM) constructs on increasing the uptake of vaccine.Citation22–24 Therefore, based on HBM, we assessed the MCWs’ acceptance and influencing factors of getting COVID-19 vaccines in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study was the first large-scale, multi-center, cross-sectional survey during the early phase of the available COVID-19 vaccine, presenting the vaccine uptake intention of the COVID-19 vaccine among MCWs in China. The findings will be helpful for policy makers to make effective rules and develop appropriate interventions on vaccines promotion during the epidemics.

Methods

Study design and participants

A multicenter, cross-sectional, population-based online survey among MCWs was conducted using a self-administered questionnaire via an investigation platform named Wenjuanxing from January 4 to 1 May 2021. Snowball convenient sampling was utilized to recruit MCWs from selected hospitals in seven cities (from Henan Province, Sichuan Province, Shandong Province, Guangdong Province, Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, and Liaoning Province, respectively) located in seven geographical territories of China. The sample size was calculated using a margin of error of 5%, a confidence level of 95%, a response rate of 50%, and a previous estimate rate of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance of 67.8%, giving a minimum sample size of 671.Citation25,Citation26 The snowball sampling was used to recruit the potential study participants. We initially invited investigators from the seven cooperative institutions, and they distributed the questionnaire to the people meeting the inclusion criteria. Medical workers were recruited from hospital departments such as respiratory and critical care medicine, general surgery, and nephrology department. In contrast, hospital administrators who were lack of clinical experience were excluded from our study. The eligibility criteria included age more than or equal to 18 and an ability to read, understand and complete an online questionnaire. Those who were younger than 18, had barriers to using mobile phones or computers, or had cognitive impairment were excluded.

Measurements

Based on the previous studies on willingness of the COVID-19 vaccination,Citation14,Citation24,Citation27,Citation28 we specifically focused on the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine and its associated factors with health beliefs in this study. The survey questionnaire contained sociodemographic information, willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine, the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale, questions based on HBM, and items about the trust. We also collected information about vaccine-related events (public data and news) on the COVID-19 vaccine, including daily change of COVID-19 vaccination from the website of the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China and information about COVID-19 vaccines on social media, from April 24 to May 11, in 2021.Citation29

Sociodemographic information

Sociodemographic variables included age, gender, living area, marital status, educational background, job status, annual household income, and attitudes toward the National Immunization Program (acceptance or rejection).

Willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine

The willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination was asked as: “Would you be willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine?”. The acceptance rate of the COVID-19 vaccine was defined as the proportion of participants who answered “yes” in this study. If the answer was “No” or “Not Sure”, the reasons of unwillingness of COVID-19 vaccination will be further explored.

Health beliefs on COVID-19 infection and vaccination

HBM has been widely used in studies of vaccine uptake in China.Citation24,Citation27 Based on the principle of HBM and previous literature,Citation24,Citation27,Citation28 we set 19 questions based on HBM. The HBM hypothesizes that susceptibility to disease, severe outcome, beneficial behavior, and few obstacles are positive factors that promote individuals to adopt disease-prevention behaviors, such as vaccination.Citation30 The following items were designed to explore related factors of getting the COVID-19 vaccine accordingly: (1) perceived susceptibility to COVID-19: “Do you agree that you will be probably infected with COVID-19 if you are not vaccinated against COVID-19?” “Do you agree that you will always be at high risk of getting COVID-19 if you are not vaccinated against COVID-19?” “Do you agree that your risk of suffering from COVID-19 will be reduced if you are vaccinated against COVID-19?” “Do you agree that the epidemic of COVID-19 can be limited if everyone is vaccinated against COVID-19?” (2) perceived severity of COVID-19 infection: “If you were infected with COVID-19, you would die.” “If you were infected with COVID-19, you might die.” “When you get COVID-19, your family’s health may be at risk.” “If you were infected with COVID-19, you will be at a greater risk of death.” (3) perceived benefits to COVID-19 vaccination: “Getting COVID-19 vaccine can prevent the COVID-19 infection of my family members.” “Getting COVID-19 vaccine can prevent economic losses caused by COVID-19 infection.” “Getting COVID-19 vaccine can provide better protection against COVID-19.” “Immunity from COVID-19 infection is better than immunity from COVID-19 vaccination.” (4) perceived barriers to COVID-19 vaccination: “You are worried about serious side effects after being vaccinated against COVID-19.” “It is not safe to get vaccinated against COVID-19.” “If you get the COVID-19 vaccine, it could lead you to get COVID-19.” “The epidemic of COVID-19 in China has been brought under control, so it is no longer necessary to be vaccinated against COVID-19.” (5) cues to action of COIVD-19 vaccination: “If a doctor recommends you to get the COVID-19 vaccine, you will take it.” “If you don’t see negative COVID-19 vaccine information, you will choose it.” “If you receive enough information about the COVID-19 vaccine, you will take it.”

These items mainly included perceptions of oneself and family members’ COVID-19 susceptibility, perceived severity of COVID-19 infection, perceived barriers and benefits to COVID-19 vaccination (4 items each), and cues to action (3 items). Except for the dimension of cues to action, items from the other four dimensions are measured on a five-point Likert-type rating scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). The dimension about cues to action contains three dichotomous questions. Disagree is equal to 0, and agree is 1. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the health belief model constructs was 0.827 for perceived susceptibility, 0.789 for perceived severity, 0.603 for perceived barriers, 0.625 for perceived benefits, and 0.525 for cues to action, respectively.

Vaccine hesitancy on COVID-19 vaccine

The COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS) was composed of 6 items which were revised based on the previous studies, in which it was developed by Sandra.Citation31 It was also used in a cross-sectional study about the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in China.Citation32 It has three dimensions: complacency refers to the belief that perceived risks of vaccine-preventable diseases are low and that vaccination is not a necessary preventive action; confidence refers to the trust in the effectiveness and safety of vaccines, the delivery system, and the motivations of vaccination policymakers; convenience refers to vaccine availability and accessibility.Citation33 The items of VHS were: (1) complacency: “Do you think the COVID-19 vaccine is not necessary?” “Do you think the COVID-19 vaccine is not important?” (2) confidence: “Do you think the COVID-19 vaccine is safe?” “Do you think the COVID-19 vaccine is effective?” (3) convenience: “Do you think the COVID-19 vaccination is convenient?” “Do you think the COVID-19 vaccine is affordable?” All items are measured on a five-point Likert-type rating scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.930 for complacency, 0.944 for confidence, and 0.864 for convenience, respectively.

Two items about trust related to the vaccine recommended by the government and healthcare system were also used, which was modified from the previous studies:Citation24,Citation34 “Do you want to get the COVID-19 vaccine recommended by the government?” “Do you trust the national healthcare system?” Each item is scored on a scale of 0 to 10. The Cronbach’s α was 0.825.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed by the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 (IBM) and SPSS Amos version 23 (IBM). Pearson correlation analysis was employed to examine the correlation of HBM and VHS dimensions, using SPSS 26.0 software. To examine the structures in HBM and VHS as separate congeneric models, each of them was tested with maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 23.0 software. The structural validity of the model was evaluated by the model fit indices, including GFI, AGFI, TLI, CFI, RMSEA, SRMR; The discriminant validity of the model was evaluated by the average variance extracted (AVE) method.Citation35 The outcome variable was a binary variable on willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccination. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were performed to explore the associations between individual factors and the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine. In order to avoid potential impacts among parts,Citation24 we performed three independent multivariate logistic regression analyses with (1) HBM variables (Model A); (2) COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (Model B); and (3) the trust items (Model C). All P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study participants and characteristics

A total of 2681 medical care workers completed the questionnaire survey. Among the participants, 40.0% (1072) were doctors, and 40.1% (1075) were nurses. 72.1% were female (1932), 90% were from urban (2426), with a mean age of 36 years old (). The majority (72.2%) were married, and most had received education beyond secondary level (93.8%), including the graduated from senior high school and the vocational or technical college. 80.0% of the respondents (2145 employees) had ever accepted the National Immunization Program ().

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among participants (N = 2681).

Willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine

Overall, when asked whether they would “decide to receive the COVID-19 vaccine”, 82.5% of all respondents (2213) said “yes”, 1.5% (40) said “no”, and 16.0% (428) were uncertain. The willingness of acceptance was 86.9% among doctors, 80.7% among nurses, and 77.3% among other medical staff (including researchers, ultrasound doctors, laboratory doctors, etc.), respectively. Male had a higher willingness of vaccination than female (86.1% vs. 81.2%). ()

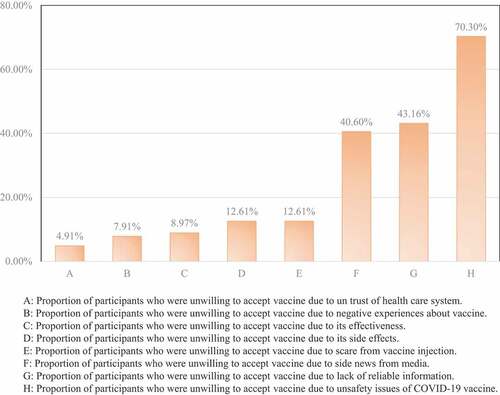

In addition, we found that the main concern of those who were unwilling to accept COVID-19 vaccination was the side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine among them (70.3%); nearly half of them thought they were lack of reliable information on the COVID-19 vaccine; 40.0% MCWs refused or hesitated against the COVID-19 vaccination due to the news of side-effect about vaccine from the media. ().

Confirmatory factor analysis on HBM and VHS

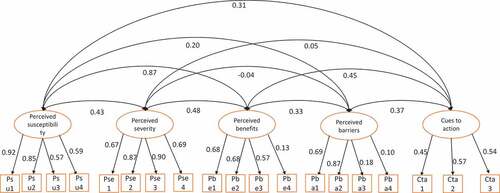

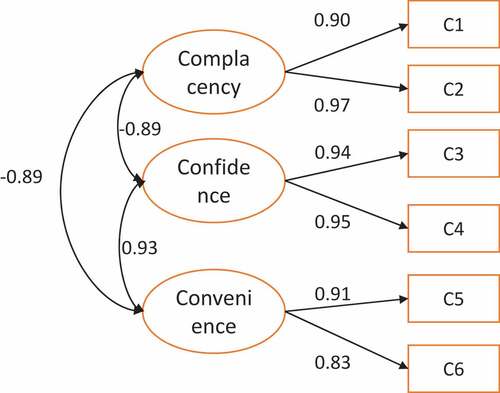

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed on HBM constructs and VHS to evaluate the validity of the model. The model fit indices in HBM were shown as follows: GFI = 0.942, AGFI = 0.918, TLI = 0.914, CFI = 0.932, RMSEA = 0.062, SRMR = 0.076; the model fit indices in VHS were GFI = 0.998, AGFI = 0.991, TLI = 0.998, CFI = 0.999, RMSEA = 0.030, SRMR = 0.003. To evaluate discriminant validity, the correlation of five dimensions in HBM was examined. When the square root of each factor’s AVE is greater than the absolute value of the correlation of this factor and the other four factors, the model demonstrates discriminant validity. As shown in , the diagonal elements in the correlation of factors matrix were the square root of AVE. All the diagonal elements were greater than the corresponding off-diagonal elements. Results of confirmatory factor analysis in HBM and VHS were shown in .

Table 2. Correlation of variables and discriminant validity in HBM by AVE.

Table 3. Correlation of variables and discriminant validity in VHS by AVE.

Univariate associations of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine

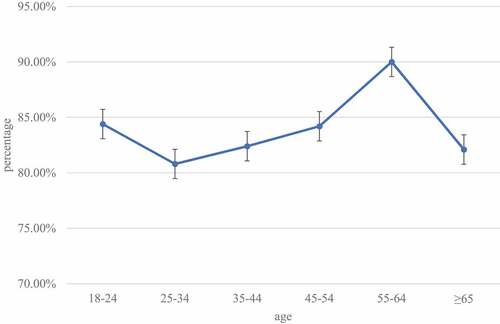

In simple logistic regression analysis, males were more willing to be vaccinated compared to their female counterparts (p < .01). Apart from the acceptance rate (80.8%) among the group aged 25–34 years, those aged between 55–64 showed more willingness to be vaccinated compared to their lower age group with marginal significance (p < .05), and the acceptance rate was 90.0%. The acceptance rates exhibited an opposite S-shape among different age groups (). Additionally, subjects living in urban, individuals with a bachelor’s degree or above educational background, doctors, medium-to-high (¥110,000–350,000) level of annual household income, and participants with acceptance of the National Immunization Program were associated with higher willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine compared to their counterparts. Respondents who perceived higher susceptibility to COVID-19 infection and had more cues to action were significantly more likely to get the COVID-19 vaccine, whereas participants who perceived more barriers to the COVID-19 vaccine were less likely to express acceptance. Respondents with a high level of complacency about the COVID-19 vaccination were less likely to get the COVID-19 vaccine, whereas participants who had higher confidence about the COVID-19 vaccine were more likely to express acceptance. Individuals with a higher level of trust in the healthcare system and the COVID-19 vaccine recommended by the government were more likely to get the vaccine ().

Figure 4. Acceptance rate of COVID-19 vaccine (%) by age groups (years) among medical care workers in China.

Table 4. Factors associated with acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine by simple logistic regression analysis.

Multivariate factors associated with the willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine

In Model A, perceived barriers (AOR = 0.875, p < .001) were maintained to be a negative factor associated with acceptance, while cues to action (AOR = 7.659, p < .001) were a significantly positive factor associated with acceptance. In Model B, confidence (AOR = 1.567, p < .001) was significantly associated with higher vaccine acceptance, while complacency (AOR = 0.828, p = .001) and convenience (AOR = 0.878, p = .041) maintained to be negative factors associated with acceptance. In Model C, trust in the COVID-19 vaccine recommended by the government (AOR = 1.494, p < .001) and the healthcare system (AOR = 1.147, p = .001) were positively associated with the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance ().

Table 5. Factors associated with acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine by multivariate logistic regression.

Vaccine-related events

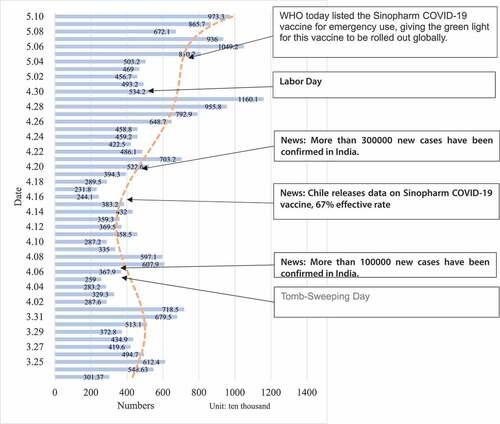

A daily increase of COVID- 9 vaccination doses among the Chinese was observed from April 23 to May 12, in 2021 (). We found that receiving information about the beneficial effect of the COVID-19 vaccine from WHO, authorities, and mass media with the news of potential threats in COVID-19 infection from surrounding countries could enhance the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination.

Discussion

MCWs are considered the most trusted sources of vaccine-related information for the public.Citation36 They are in the best position to understand the public’s attitude toward vaccination, to reflect their safety concerns, and to find ways of prompting vaccine acceptance.Citation36 The present study demonstrated a high vaccination acceptance rate (82.5%) of the COVID-19 vaccine among Chinese MCWs. This figure is substantially higher in comparison to previous studies of other countries conducted among MCWs in the same period.Citation37–39 Also, the acceptance rate among MCWs in this study was much higher than in two studies among nurses in Hong Kong (40.0% and 63.0%), among doctors in Israel (78.1%), and DRC (27.7%) in the early stage of the pandemic in 2020. This highlighted the increasing risk perception of the medical care workers during the pandemic and their need for protective measures. While the intention is a crucial driver of the uptake of health behaviors, vaccination intention is likely to be greater than actual vaccine uptake.Citation40 Therefore, it is important to identify factors associated with vaccination intention to support adjustment of policy and communications when we face the low uptake rate and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. From the current survey among MCWs, we found the proportion of MCWs indicating acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine was lower than the rate among the Chinese general public in June 2020,Citation41 and the acceptance rate among the general public in the same study (data not tabulated). This issue is still alarming due to the front-line position of MCWs in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic over the world.Citation21,Citation36,Citation42

Most of the HBM constructs were significantly associated with vaccine acceptance.Citation21,Citation24,Citation43 In this study, the five dimensions of HBM provided a framework for assessing MCWs’ intention for COVID-19 vaccines. Most constructs in HBM were significantly associated with vaccination intentions. In particular, cues to action played a significant role in vaccination promotion and the result was generally consistent with previous studies in China.Citation21,Citation43 Qin et al. found that high cues to action were proved to have the most significant effect on vaccination willingness [(COR = 61.28, 95% CI: 32.17–116.72); (AOR = 23.66, 95% CI: 9.97–56.23)].Citation43 The major influencers of cues to action were WHO, vaccine scientists, and the media.Citation44,Citation45 For instance, when WHO announced that the Sinovac vaccine was authorized for emergency use, the number of people vaccinated had risen dramatically (). By contrast, the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories, which are closely associated with distrust in science, drives people’s tendency to disobey vaccination requirements.Citation45 Therefore, by eliminating misinformation and promoting correct information about the vaccine, the government’s regulatory capacity and credibility will play a more positive role in vaccinations. The current study and previous ones also found that participants who perceived susceptible to COVID-19 were significantly more likely to accept the vaccine.Citation21,Citation24,Citation43 For example, people would get vaccinated to protect themselves before traveling on holiday ().

From VHS, we found confidence in the vaccine made significant contributions to vaccination acceptance among MCWs, which was also shown in previous studies.Citation31 Confidence in vaccines depends on trust in health care professionals, the healthcare system, science, and on socio-political context.Citation46 The current study also found that participants who trusted in the COVID-19 vaccine recommended by the government and the healthcare system were more likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccine. Therefore, in order to increase vaccine confidence, it is important to increase the trust in the government as well as in the healthcare system, which can further enhance their vaccine acceptance. However, the COVID-19 vaccine was often believed different from other “old” vaccines due to the lack of vaccine information from the authority, and the COVID-19 vaccines were produced rapidly in a short period of time after the outbreak. Due to numerous vaccine manufacturers emerged,Citation14 potential vaccine recipients were more likely to doubt the vaccine, which could compromise their vaccination rate.Citation24 Moreover, previous studies showed a significant relationship between mass media and public doubts about vaccine safety and they also showed a substantial relationship between foreign disinformation campaigns and declining vaccination rates.Citation12,Citation42,Citation47 To solve these doubts and concerns, scientific researches and expertise about vaccines play an important role.Citation48 Government should proactively provide information about their selected vaccine via related vaccine scientists to break this barrier. According to other former studies, it showed that trust in science should be considered as a necessity as soon as a vaccine becomes available.Citation16,Citation49 However, scientific evidence is sometimes uncertain and often discordant, and this may change the public perception of scientific knowledge for a long time.Citation50 Therefore, the shift in trust is important to be considered in dealing with the low acceptance issues. Based on previous research, it seems useful that the impact of political orientation, trust in science/scientists, transparency of relevant information and vaccine-related information from the national center for disease control could buffer the drivers of hesitancy and enhance the trust of the public in vaccination.Citation36,Citation51–54

The age-acceptance curve exhibited an opposite S shape showing gradually with age. The higher level of vaccine acceptance among the youngest adult group aged 18–24 years could be interpreted by the experience that they have better exposure to vaccine education and received free vaccines under the National Immunization Program since they were born.Citation55 The lowest level of vaccine willingness among the group aged 25–34 years might be attributed to married people of reproductive age, who are facing pregnancy or pregnant. In addition, compared with the doctors, the nurses also showed a weaker intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine. Since most nurses are women, pregnancy concerns could be the main reasons they hesitated to get the vaccine.Citation27 Especially in pregnant women with advanced maternal age, they are more worried about the side effects of the vaccine on their future infants.Citation27 Those findings are consistent with results from previous studies.Citation14,Citation20 However, nurses always contact patients with different illnesses, with various social-economic status, and directly access to the patients’ blood sample, hence have a high risk of being infected by the COVID-19 virus.Citation56 Besides, the high vaccine hesitancy rate among nurses could negatively impact vaccination compliance of individuals who engage with those nurses on a professional or personal level.Citation42 Therefore, we should pay more attention to the willingness of nurses and health care workers who have more contact with patients to receive the vaccine, and the dissemination of information through medical agencies and professional societies may potentially have a significant contribution in increasing the uptake of MCWs.

The findings of this study are helpful to assess the acceptance of MCWs for the COVID-19 vaccination and the potential factors influencing individuals’ vaccination behavior, which could provide a basis for the design of subsequent immunization strategies. Since our study focused on the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination, the actual vaccination behavior could be a bit different from the rate of acceptance. Although acceptance of vaccination did not equal to the behavior of vaccination, they were significantly related.Citation57,Citation58 Future research should be conducted to determine which factors affect the conversion of vaccination intention to the behavior of vaccination via longitudinal study.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, acceptance of getting the COVID-19 vaccine was self-reported by participants, and hence the information bias probably existed in this study. Second, as we utilized snowball sampling, our study population may not be representative of all MCWs, which limited the generalizability of our findings. Third, this was a cross-sectional survey based on self-reported information; hence, causality inference can hardly be drawn. Besides, the Cronbach’s α of the items measuring cues to action was 0.525, which was lower than the satisfactory criteria normally used in psychometrics, showed a relatively low internal consistency.Citation59

Conclusion

In summary, this study had examined the rate of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and the associated factors of vaccine uptake intention. The present study indicated a high acceptance rate among MCWs in China and highlighted the significance of governmental recommendations on vaccine uptake. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among MCWs could be impaired by worries on vaccination accessibility, safety and efficacy issues, and their own perceived risks of contracting the COVID-19. Also, the trust in the vaccine recommended by the government and the health care system were important for their decision of vaccination uptake. The findings of this study provided evidence-based suggestions on the implementation of vaccination strategies that aim to enhance vaccine uptake during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors’ contributions

XYS were responsible for the study design, obtaining funding and data collection. XYS, YMH, HW and WJX developed the research questions and hypotheses. HW and YMH drafted the manuscript and analyzed data under the supervision of XYS. WJX, XFG, LM, LL, CXY, YLQ, YQY and SKZ contributed to the questionnaire design and data collection. HW, YMH and WJX performed the data analysis and the interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Chinese Center for Disease Control (approval number: 202020). An electronic informed consent was provided before the start of the questionnaire survey, upon completion of the informed consent, participants filled in the online questionnaire.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

After publication, the survey data will be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author and will be produced on request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wang W, Wu Q, Yang J, Dong K, Chen X, Bai X, Chen X, Chen Z, Viboud C, Ajelli M. Global, regional, and national estimates of target population sizes for covid-19 vaccination: descriptive study. BMJ. 2020;371:m4704. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4704.

- Alzubaidi H, Samorinha C, Saddik B, Saidawi W, Abduelkarem AR, Abu-Gharbieh E, Sherman SM. A mixed-methods study to assess COVID-19 vaccination acceptability among university students in the United Arab Emirates. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(11):4074–11. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1969854.

- Randolph HE, Barreiro LB. Herd immunity: understanding COVID-19. Immunity. 2020;52(5):737–41. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.012.

- WHO. WHO lists additional COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use and issues interim policy recommendations. 2021. https://wwwwhoint/news/item/07-05-2021-who-lists-additional-covid-19-vaccine-for-emergency-use-and-issues-interim-policy-recommendations.

- National Health Commission of People’s Republic of China. [Accessed 2022 Mar 1]. https://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqjzqk/list_gzbds.html.

- Medicine LSoHT. COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker. [Accessed 2022 Mar 1]. https://vac-lshtmshinyappsio/ncov_vaccine_landscape/.

- Wheeler M, Buttenheim AM. Parental vaccine concerns, information source, and choice of alternative immunization schedules. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1782–89. doi:10.4161/hv.25959.

- Pal S, Shekhar R, Kottewar S, Upadhyay S, Singh M, Pathak D. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and attitude toward booster doses among US healthcare workers. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(11):1358–68. doi:10.3390/vaccines9111358.

- Paterson P, Meurice F, Stanberry LR, Glismann S, Rosenthal SL, Larson HJ. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine. 2016;34(52):6700–06. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042.

- Jarrett C, Wilson R, O’-Leary M, Eckersberger E, Larson HJ, Swgv H. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy – a systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4180–90. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.040.

- MacDonald NE, Hesitancy SWGV. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Peretti-Watel P, Seror V, Cortaredona S, Launay O, Raude J, Verger P, Fressard L, Beck F, Legleye S, L’Haridon O. A future vaccination campaign against COVID-19 at risk of vaccine hesitancy and politicisation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):769–70. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30426-6.

- Palgi Y, Bergman YS, Ben-David B, Bodner E. No psychological vaccination: vaccine hesitancy is associated with negative psychiatric outcomes among Israelis who received COVID-19 vaccination. J Affect Disord. 2021;287:352–53. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.064.

- Paris C, Benezit F, Geslin M, Polard E, Baldeyrou M, Turmel V, Tadié É, Garlantezec R, Tattevin P. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers. Infect Dis Now. 2021;51(5):484–87. doi:10.1016/j.idnow.2021.04.001.

- Youssef D, Abou-Abbas L, Berry A, Youssef J, Hassan H. Determinants of acceptance of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) vaccine among Lebanese health care workers using health belief model. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0264128. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264128.

- Palamenghi L, Barello S, Boccia S, Graffigna G. Mistrust in biomedical research and vaccine hesitancy: the forefront challenge in the battle against COVID-19 in Italy. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):785–88. doi:10.1007/s10654-020-00675-8.

- Lucia VC, Kelekar A, Afonso NM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. J Public Health (Oxf). 2021;43(3):445–49. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdaa230.

- Chew NWS, Cheong C, Kong G, Phua K, Ngiam JN, Tan BYQ, Wang B, Hao F, Tan W, Han X. An Asia-Pacific study on healthcare workers’ perceptions of, and willingness to receive, the COVID-19 vaccination. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;106:52–60. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.069.

- Meyer MN, Gjorgjieva T, Rosica D. Trends in health care worker intentions to receive a COVID-19 vaccine and reasons for hesitancy. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e215344. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5344.

- Kwok KO, Li KK, Wei WI, Tang A, Wong SYS, Lee SS. Editor’s choice: influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: a survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;114:103854. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103854.

- Nohl A, Afflerbach C, Lurz C, Brune B, Ohmann T, Weichert V, Zeiger S, Dudda M. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination among front-line health care workers: a nationwide survey of emergency medical services personnel from Germany. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(5). doi:10.3390/vaccines9050424.

- Wong LP, Alias H, Wong PF, Lee HY, AbuBakar S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(9):2204–14. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1790279.

- Chu H, Liu S. Integrating health behavior theories to predict American’s intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(8):1878–86. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2021.02.031.

- Wong MCS, Wong ELY, Huang J, Cheung AWL, Law K, Chong MKC, Ng RWY, Lai CKC, Boon SS, Lau JTF. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: a population-based survey in Hong Kong. Vaccine. 2021;39(7):1148–56. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.083.

- Guay M, Gosselin V, Petit G, Baron G, Gagneur A. Determinants of vaccine hesitancy in Quebec: a large population-based survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(11):2527–33. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1603563.

- Taherdoost H. Determining sample size; how to calculate survey samplesize. Int J Econ Manage Syst. 2017;2:3.

- Wang R, Tao L, Han N, Liu J, Yuan C, Deng L, Han C, Sun F, Chi L, Liu M. Acceptance of seasonal influenza vaccination and associated factors among pregnant women in the context of COVID-19 pandemic in China: a multi-center cross-sectional study based on health belief model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):745. doi:10.1186/s12884-021-04224-3.

- Huang Y, Su X, Xiao W, Wang H, Si M, Wang W, Gu X, Ma L, Li L, Zhang S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among different population groups in China: a national multicenter online survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):153. doi:10.1186/s12879-022-07111-0.

- National Health Commission of People’s Republic of China. 2021 May 12. https://www.nhcgovcn/xcs/yqjzqk/list_gzbds.html.

- Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175–83. doi:10.1177/109019818801500203.

- Quinn SC, Jamison AM, An J, Hancock GR, Freimuth VS. Measuring vaccine hesitancy, confidence, trust and flu vaccine uptake: results of a national survey of White and African American adults. Vaccine. 2019;37(9):1168–73. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.033.

- Liu XX, Dai JM, Chen H, Li XM, Chen SH, Yu Y, Zhao QW, Wang RR, Mao YM, Fu H. Factors related to public COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy based on the “3cs”model: a cross-sectional study. Fudan Univ J Med Sci. 2021;48:307–12. doi:10.3969/j.issn.16728467.2021.03.004.

- González-Block M, Gutiérrez-Calderón E, Pelcastre-Villafuerte BE, Arroyo-Laguna J, Comes Y, Crocco P, Fachel-Leal A, Noboa L, Riva-Knauth D, Rodríguez-Zea B. Influenza vaccination hesitancy in five countries of South America. Confidence, complacency and convenience as determinants of immunization rates. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0243833. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0243833.

- Han H. Testing the validity of the modified vaccine attitude question battery across 22 languages with a large-scale international survey dataset: within the context of COVID-19 vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(1):1–4. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2024066.

- Fornell C. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Market Res. 1981;18:12.

- Papagiannis D, Rachiotis G, Malli F, Papathanasiou IV, Kotsiou O, Fradelos EC. Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination among Greek health professionals. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(3):200–03. doi:10.3390/vaccines9030200.

- Garcia LY, Cerda AA. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine: a multifactorial consideration. Vaccine. 2020;38(48):7587. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.026.

- Guidry JPD, Laestadius LI, Vraga EK, Miller CA, Perrin PB, Burton CW, Ryan M, Fuemmeler BF, Carlyle KE. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(2):137–42. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2020.11.018.

- Sherman SM, Smith LE, Sim J, Amlot R, Cutts M, Dasch H, Rubin GJ, Sevdalis N. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVaccs), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(6):1612–21. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1846397.

- Sniehotta FF, Scholz U, Schwarzer R, Fuhrmann B, Kiwus U, Völler H. Long-Term effects of two psychological interventions on physical exercise and self-regulation following coronary rehabilitation. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12(4):244–55. doi:10.1207/s15327558ijbm1204_5.

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225–28. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9.

- Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, Morozov NG, Mizrachi M, Zigron A, Srouji S, Sela E. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):775–79. doi:10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y.

- Qin C, Wang R, Tao L, Liu M, Liu J. Acceptance of a third dose of COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors in China based on health belief model: a national cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(1). doi:10.3390/vaccines10010089.

- Al-Metwali BZ, Al-Jumaili AA, Al-Alag ZA, Sorofman B. Exploring the acceptance of COVID -19 vaccine among healthcare workers and general population using health belief model. J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27(5):1112–22. doi:10.1111/jep.13581.

- Han H. Trust in the scientific research community predicts intent to comply with COVID-19 prevention measures: an analysis of a large-scale international survey dataset. Epidemiol Infect. 2022;150:e36. doi:10.1017/S0950268822000255.

- Verger P, Dubé E. Restoring confidence in vaccines in the COVID-19 era. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2020;19(11):991–93. doi:10.1080/14760584.2020.1825945.

- Wilson SL, Wiysonge C. Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(10):e004206. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004206.

- Plohl N, Musil B. Modeling compliance with COVID-19 prevention guidelines: the critical role of trust in science. Psychol Health Med. 2021;26(1):1–12. doi:10.1080/13548506.2020.1772988.

- Goodman JL, Borio L. Finding effective treatments for COVID-19: scientific integrity and public confidence in a time of crisis. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1899–900. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6434.

- Provenzi L, Barello S. The science of the future: establishing a citizen-scientist collaborative agenda after covid-19. Front Public Health. 2020;8:282. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00282.

- Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, Lahiri D, Lavie CJ. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):779–88. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035.

- Harper CA, Satchell LP, Fido D, Latzman RD. Functional fear predicts public health compliance in the covid-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2021;19(5):1875–88. doi:10.1007/s11469-020-00281-5.

- Gadarian SK, Goodman SW, Pepinsky TB, Lupu N. Partisanship, health behavior, and policy attitudes in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0249596. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0249596.

- West RM, Kobokovich A, Connell N, Gronvall GK. Antibody (Serology) tests for covid-19: a case study. M Sphere. 2021;6(3):e00201–21. doi:10.1128/mSphere.00201-21.

- Yeung KHT, Tarrant M, Chan KCC, Tam WH, Nelson EAS. Increasing influenza vaccine uptake in children: a randomised controlled trial. Vaccine. 2018;36(37):5524–35. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.066.

- Si MY, Su XY, Jiang Y, Wang WJ, Gu XF, Ma L. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):113. doi:10.1186/s40249-020-00724-0.

- Lu X, Lu J, Zhang L, Mei K, Guan B, Lu Y. Gap between willingness and behavior in the vaccination against influenza, pneumonia, and herpes zoster among Chinese aged 50–69 years. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021;20(9):1147–52. doi:10.1080/14760584.2021.1954910.

- Si M, Jiang Y, Su X, Wang W, Zhang X, Gu X, Ma L, Li J, Zhang S, Ren Z. Willingness to accept human papillomavirus vaccination and its influencing factors using information–motivation–behavior skills model: a cross-sectional study of female college freshmen in mainland China. Cancer Control. 2021;28:10732748211032899. doi:10.1177/10732748211032899.

- Streiner DL. Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J Pers Assess. 2003;80(1):99–103. doi:10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18.