ABSTRACT

This study aims to provide evidence of hesitancy in receiving the COVID-19 booster vaccine and associated factors in the vaccinated population that have completed a primary vaccination series. An anonymous web-based survey was disseminated to Malaysian adults aged ≥18 years via social media platforms. A total of 1010 responses were collected, of which 43.0% (95%CI 39.9–46.0) declared a definite willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster, 38.2% (95%CI 35.2–44.3) reported being somewhat willing and only 5.7% (95%CI 4.5–7.4) reported being definitely unwilling. Demographically younger participants, those of higher income, Chinese ethnicity and those from the central region reported significantly higher odds of a definite willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine booster compared to the reference group (somewhat willing/undecided/somewhat unwilling/definitely unwilling). Having no side effects with past COVID-19 vaccination was associated with a significantly higher odds of definite willingness (OR = 2.82, 95% CI 1.33–5.99). A lower (range 6–22) pandemic fatigue score (OR = 2.34, 95% CI 1.75–3.22) and higher (range 24–30) preventive practices score (OR = 2.45, 95% CI 1.80–3.34) were also associated with higher odds of definite willingness. Regarding attitudes toward COVID-19 booster vaccine, having fewer concerns about the side effects of booster vaccination and the uncertain long-term safety of multiple COVID-19 vaccinations were found to create greater odds of a definite willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine booster. Findings from this study provided insights into demographic characteristics and important behavioral and attitudinal factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine booster hesitancy.

Introduction

Vaccines to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection are considered the most promising approach to mitigate the pandemic and prevent severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. However, immunological studies have documented a steady decline in antibody levels among vaccinated individuals.Citation1,Citation2 Waning immunity over time and the emergence of different SARS-CoV-2 variants, such as B.1.1.7, B.1.351 and B.1.617.2, leave people at risk of infection even after vaccination.Citation3,Citation4 Controlling the spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern requires a booster dose after primary vaccination series.Citation4–6 COVID-19 vaccine boosters were shown to have immunological benefits, and the vaccines showed acceptable side-effect profiles.Citation7

Malaysia’s population in 2021 is estimated to be 32.7 million.Citation8 Malaysia rolled out its COVID-19 vaccination program in early March 2021, when the country had reported over 3.7 million confirmed cases and 1,255 deaths, becoming one of the most affected countries in the Western Pacific region.Citation9 Currently, the Malaysian government has not made COVID-19 vaccination mandatory; however, unvaccinated individuals will lose out on privileges, including not being allowed to enter shopping malls, dine in restaurants or enter a place of worship.Citation10 As of 10 March 2022, Malaysia has administered at least 68 million doses of the COVID-19 vaccines, with over 27 million people having received at least one dose, 25 million having completed two doses and 15 million having received a booster dose.Citation11 Likewise, the Malaysian government has not made booster doses a mandatory condition for the complete dosage of COVID-19 vaccines for the Malaysian public. Previous studies have reported a high primary COVID-19 vaccination intent of between 83.3% and 94.3% among Malaysian public.Citation12–15 Little is known about the intention to receive a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, attitudes toward receiving a booster dose and associated factors among the Malaysian public.

The COVID-19 pandemic has enormously affected the lifestyles and well-being of the public. Pandemic fatigue is an expected and natural response to a prolonged public health crisis.Citation16 The notion of behavioral fatigue associated with adherence to COVID-19 restrictions or pandemic fatigue is a social concern.Citation17 People who feel fatigued may start to have doubts regarding the effectiveness of COVID-19 mitigation strategies and become unwilling to do what it takes to end the pandemic, including being vaccinated. Pandemic fatigue is thus a potential correlate of vaccine acceptance and can impede vaccination intention from turning into behavior.Citation18 Pandemic fatigue and vaccine hesitancy have been reported as the most challenging current issues, potentially worsening COVID-19 situation.Citation18,Citation19 It has been 2 years since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the spread of COVID-19 is still strong in Malaysia and worldwide. As yet, no studies have investigated pandemic fatigue among the Malaysian public and the link between pandemic fatigue, prevention practices to mitigate infection and COVID-19 vaccination intention.

It is well established that positive vaccination attitudes increase the rate of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in studies conducted in countries around the world.Citation20–23 Among vaccine attitudes, the existing literature indicates that the fear of COVID-19 vaccination side effects is the main cause of hesitation and refusal factors in individuals’ vaccination decision-making processes.Citation24,Citation25 We hypothesize that COVID-19 booster vaccine intentions or vaccine trust are predicted by positive attitudes toward vaccination.

This study assesses the willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster dose and associated factors in Malaysia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Demographics, self-perceived health status, experience of SARS-CoV-2 infection, experience of side-effects with COVID-19 vaccination, pandemic fatigue, practices of recommended measures against COVID-19 and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccine boosters were the factors investigated that could influence willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine booster dose.

Methods

Study participants and survey design

Convenience sampling was used for the data collection. We commenced a cross-sectional, web-based anonymous survey using an online questionnaire, and the data collection was conducted between 22 November 2021 and 9 February 2022. The inclusion criteria were that the respondents were Malaysian residents above the age of 18 years of age and who had received a completed recommended dose of primary COVID-19 vaccination series (currently one or two doses of COVID-19 vaccine depending on the product). The researchers used social network platforms (Facebook and WhatsApp) to disseminate and advertise the survey link to the general public. Both professional and personal networks of the researchers, students and alumni were used to reach the target participants. Respondents who completed the survey received a note encouraging them to disseminate the survey link to all their friends and family members. The questionnaire was developed in English and was then translated into Bahasa Malaysia, the national language of Malaysia. Questions were presented bilingually in English and Bahasa Malaysia. Prior to administration of the questionnaire, local experts validated the content of the questions, and the questionnaire was pilot tested with members of the general public. A 32-item questionnaire was designed on Google Forms, which consisted of seven pages, with the number of questions in each page ranging from 1 to 7.

In the current study, the estimated sample size was derived from the online Raosoft sample size calculator.Citation26 The calculated sample size was 385 based on a normal approximation of the binomial distribution with a finite population correction applied,Citation27 assuming an observer proportion of respondents selecting a specific response option of 50%, a 95% confidence level, a margin of error of 5% and population size of 32.4 million population in Malaysia.Citation28 The sample size was multiplied by the predicted design effect of two to account for the use of convenience sampling and an online survey.Citation29 The minimum survey sample size was therefore set to 770 (385 × 2) participants.

Measures

The survey consisted of questions (Appendix 1) that assessed (1) demographic characteristics, general health status; (2) ever having been infected with SARS-CoV-2, experience of side-effect with primary COVID-19 vaccination; (3) pandemic fatigue and practice of recommended measures against COVID-19; (4) attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine booster; and (5) intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster.

Primary COVID-19 vaccination side effects

Participants were asked to rate the severity of the side-effects they experienced in their past primary COVID-19 vaccination on a scale from 0 (no side effects at all) to 10 (very severe side effects). The scale was classified as 0, no side effect at all; 1–5 = mild to moderate; and 6–10 = moderate to severe.

Pandemic fatigue

Pandemic fatigue is an expected and natural response to a prolonged public health crisis.Citation13 In this study, the items related to COVID-19 pandemic fatigue assessed whether participants were feeling demotivation and exhaustion with the demands of life during the pandemic. To date, there is no established measurement for assessing COVID-19 pandemic fatigue, and the scale used was adapted from a previous study.Citation30 The scale consists of six items, and participants responded to these items using a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The total score ranges from 6 to 42, with higher scores indicating a higher level of pandemic fatigue.

Practice of recommended measures against COVID-19 infection

The practice of recommended measures against COVID-19 infection was measured using 10 self-developed items that covered preventive measures such as wearing facial masks, practicing hand hygiene, social distancing and avoiding crowded places. Respondents self-reported their current practices at the time of the survey, using a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = never, 1 = seldom, 2 = some of the time and 3 = most of the time). The total score ranges from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating a higher level of prevention practices.

Attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine booster

To measure attitudes related to the COVID-19 vaccine booster, we queried the perceived worry or concern of side effects when receiving COVID-19 vaccine booster and unknown long-term side effects over multiple COVID-19 vaccinations (3 items). Options were strongly agree, agree, disagree and strongly disagree.

Intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster

The intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster was measured using a one-item question (If you receive an invitation in MySejahteraCitation31 [Malaysia’s COVID-19 tracking linked to individual identities, an application developed by the Government of Malaysia to assist in managing the COVID-19 outbreaks in the country] to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster, would you be willing to take it?) on a 5-point scale (definitely not to yes definitely). The MySejahtera app is linked to individual identities

To ensure valid and reliable responses, we carried out data cleaning before analyses. Straightlining and duplicate responses were checked and removed. Force answering option was implemented in our online survey where all questions need to be answered by the study participants before moving on to the next page to avoid incomplete responses.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to examine the distribution of all variables of interest, including normality, means and frequencies. The data for pandemic fatigue and prevention practices scores were not normally distributed, so the median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to describe these scores. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for the pandemic fatigue and prevention practices scales to assess reliability in terms of internal consistency. The pandemic fatigue scale had adequate to very good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.904. The prevention practices scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.844. The chi-square test was used to compare the intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster between groups. Binary logistic regression and multivariable logistic regression were used to explore the factors affecting the intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine booster (1 = definitely willing; 0 = somewhat willing/undecided/somewhat unwilling/definitely unwilling). The variables with p < .05 in the binary logistic regression analyses were entered into the multivariable logistic regression model. The odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed for each independent variable. The model fit was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. The Hosmer–Lemeshow statistic indicated a poor fit if the significance value is less than 0.05. All analyses were also conducted using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was established at a p-value <.05.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the University of Malaya Research Ethics Committee (UM.TNC2/UMREC − 1666). Participants were informed that the survey did not collect any identifying information. All participants consented to participation by clicking on the consent agreement to participate in the research. The participants were not offered any form of incentives for their participation. They were also informed that their participation was voluntary.

Results

A total of 1,010 complete responses were received. shows the demographics of the study participants. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 78 years (mean = 32.1, SD ±11.3). The majority (85.2%) were between 18 and 44 years, female (63.7%) and of Malay ethnic origin (44.0%). Based on the occupation categories, over one-third were in professional and managerial occupations (37.9%), while students comprised 31.2% of the participants. A total of 40.3% reported an average monthly household income of MYR1001–5000. Most participants were from urban (77.1%) and suburban (16.0%) areas, and a majority of the participants were from the central region (69.5%). Most participants (90.9%) did not have any chronic diseases, and only 14.4% reported having had SARS-CoV-2 infection experience.

Table 1. Factors associated with the willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine booster dose (N = 1010).

In total, 95.1% (n = 961) had experienced vaccine-related side effects in their past primary COVID-19 vaccination, with 48.6% rating their side effects as mild to moderate (1–5) and 46.5% rating them as moderate to severe (6–10).

Pandemic fatigue

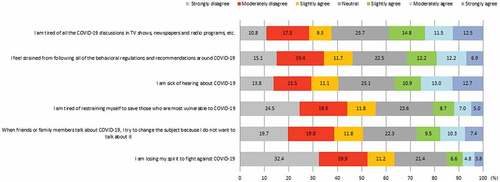

shows the proportion of the level of agreement for the six pandemic fatigue items. A total of 12.7% reported strongly agreeing that they are sick of hearing about COVID-19, and 12.5% reported being tired of all COVID-19 discussions in the media, including TV shows, newspapers and radio programs. The mean total pandemic fatigue score range was 6 to 42, and the median was 22.0 (IQR = 12.0–27.0). The pandemic fatigue score was categorized as a score of 6–22 or 23–42, based on the median split; as such, a total of 519 (51.4%; 95%CI 48.3–54.5) were categorized as having a score of 6–22 and 491 (48.6%; 95%CI 45.5–51.7) were categorized as having a score of 23–42 ().

Practice of recommended measures against COVID-19 infection

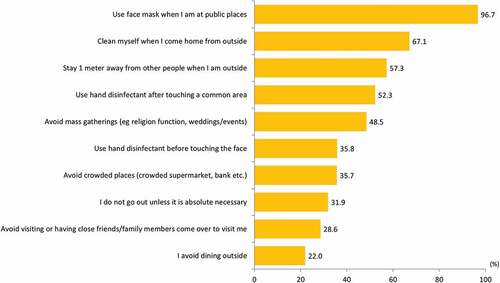

shows that the most practiced preventive measure was using a face mask (96.7%). A low proportion of respondents reported avoiding crowded places (5.7%) and not going out unless it absolutely necessary (31.9%). Avoid dining out (22.0%) and visiting or receiving visitors (28.6%) were the least practiced preventive measures. The mean total prevention practices score range was 0 to 30, and the median was 23.0 (IQR = 19.0–27.0). The preventive measures score was categorized as a score of 0–23 or 24–30, based on the median split; as such, a total of 552 (54.7%; 95%CI 51.5–57.8) were categorized as having a score of 6–22 and 458 (45.3%; 95%CI 42.2–48.5) were categorized as having a score of 23–30 ().

Attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine booster

As shown in the first and second columns of , slightly over a third (35.5%) reported fear of side effects following booster vaccination, and 33.3% reported fear of severe side effects that would need medical attention following booster vaccination. Half (50.6%) reported fear of unknown long-term side effects over multiple COVID-19 vaccinations.

Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine booster and influencing factors

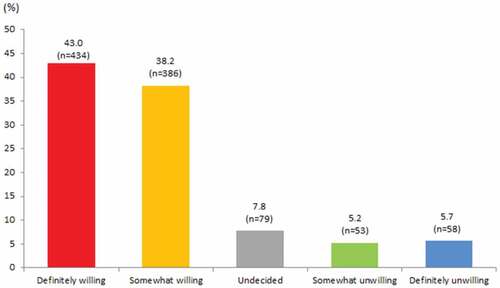

shows the proportion of responses for intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster. On the whole, 434 (43.0%) participants responded that they would be definitely willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster, while 386 (38.2%) responded somewhat willing. Only 58 (5.7%) responded definitely unwilling. The third and fourth columns of show the univariable and multivariable factors influencing willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster. In demographics, participants aged 18–24 years were found to have the highest significant odds of a definite willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine booster. Those of Chinese (OR = 3.42, 95% CI 1.67–7.02) followed by Malay (OR = 2.85, 95% CI 1.42–5.72) ethnicity reported the highest odds of a definite willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine booster. There was a significant gradual increase in the odds of a definite willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine booster by average household income. Participants from the central region reported the highest significant odds of a definite willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine booster (OR = 1.98, 95% CI 1.14–3.46)

Participants’ health status and experience with SARS-CoV-2 infection did not influence COVID-19 booster administration intention; however, participants who experienced no side effects in their previous primary COVID-19 vaccination reported significantly higher odds of a definite willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster (OR = 2.82, 95% CI 1.33–5.99) than those who experienced moderate-to-severe side effect.

Participants with a pandemic fatigue score of 6–22 were found to have a higher definite willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster (OR = 2.34, 95% CI 1.75–3.22) than those with score of 23–30. A preventive practices score of 24–30 was associated with higher odds of definite willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster (OR = 2.45, 95% CI 1.80–3.34) than a score of 0–23. Participants who had less fear of severe side effects (OR = 1.87, 95% CI 1.12–3.14) or uniquely severe side effects that would need medical attention (OR = 1.87, 95% CI 1.09–3.21) following a booster vaccination reported higher odds of definite willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster. Having a lower level of fear of unknown long-term side effects over multiple COVID-19 vaccinations was also associated with greater odds of a definite willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster (OR = 1.87, 95% CI 1.09–3.21). A higher proportion of participants with no fear of long-term side effects over multiple COVID-19 vaccinations reported a definite willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster; however, this was not a significant association in the multivariable model.

Discussion

This study assessed the intention of individuals who had completed the primary COVID-19 vaccination regime toward receiving a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and identified potential factors that might influence this intention as soon as booster COVID-19 vaccine doses are available to the public in Malaysia.

Other population surveys around the world have found varying rates of willingness to receive a booster dose, ranging from only 44.6% among the public in Jordan,Citation32 61.8% in adult AmericansCitation33 and 71% among adults in Poland,Citation34 with the highest willingness (91.1%) in the general population in China.Citation35 Our study, which used a slightly different intention scale, found that a large proportion (82.2%) indicated that they were willing (43.0% definite willingness and 38.2% somewhat willing) to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster dose. Our previous study on the willingness to receive primary COVID-19 vaccination in Malaysia that uses a similar intention scale found 48.2% indicated a definite intent followed by 46.1% reporting a probable intent.Citation15 Our results indicate that the Malaysian public reported a near similar intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine booster dose as for receiving the primary COVID-19 vaccine. Achieving very high vaccination coverage for primary vaccination and booster doses represents the most important public health strategy to control the pandemic. Efforts are still needed to address hesitancy toward receiving a booster dose, particularly among those who expressed definite and partial unwillingness and those who remain undecided, as these groups comprise 18.7% of the overall participants.

Although our study found a high willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster, there were noticeable demographic and geographical disparities in acceptance. In this study, as average monthly household income increases, so does the willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine booster. Acceptance is also relatively high in the central region, the most populous and urbanized in the country. These findings demonstrate that lower-income people living in rural and remote areas, which are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19,Citation36 may be disproportionately impacted by the pandemic due to lack of willingness to receive the vaccine, even if the COVID-19 vaccine is widely available for everyone in the country.

Previous findings on ethnic disparities in the intention to receive primary COVID-19 vaccination in Malaysia have been inconclusive, with some studies reporting Malays being more willing,Citation13,Citation14 while another reported a non-significant difference.Citation15 In this study, the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine booster among Malaysian Chinese was significantly higher than among other ethnicities. Additional investigations in a larger sample are warranted to confirm our results. The COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with unfavorable racial discrimination in many countries,Citation37,Citation38 so considerable attention needs to be paid to avoid ethnic disparities in COVID-19 vaccinations and ultimate ethnic inequalities in the impact of the COVID-19 crisis in Malaysia.

This study also found that younger participants reported a higher acceptance rate of a COVID-19 vaccine booster. A possible explanation is that younger participants are healthier and have lesser comorbidities, and would thus be more willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster. It is important to highlight that in this study, having chronic diseases was not significantly associated with COVID-19 vaccine booster acceptance. The nonsignificant association is most likely because the majority of our study participants were people aged 18–44 years and did not have any type of chronic disease. A previous study in Malaysia reported that people with existing chronic diseases had significantly lower COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates than those who were healthy.Citation39

The findings of lower willingness in a COVID-19 vaccine booster among the older age participants warrant attention. Older adults are most vulnerable to morbidity and mortality globally, and likewise in Malaysia.Citation40 The elderly in Malaysia have been prioritized for vaccination in the COVID-19 national vaccination program. A survey conducted during the primary-dose COVID-19 vaccination program found that reports of adverse events have led elderly people in Malaysia to express concerns about getting vaccinated.Citation41 The findings imply the need to address the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine booster for older adults, particularly those with multiple comorbidities and frailty, to enhance their uptake. The administration of COVID-19 vaccine booster doses in the elderly is advisable, as a large-scale study suggests that booster vaccination generated greater protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and reduced COVID-19 hospitalization, ICU admission and death in older people.Citation42 Interventions designed specifically for older adults to address their worries and concerns related to the vaccine are of paramount importance.

Pandemic fatigue and a hypothesized reduction in adherence to protective behaviors against COVID-19 have raised worldwide concerns,Citation43 and are likewise evident in this study. Higher levels of pandemic fatigue along with lower levels of prevention practices were found to be associated with lower booster vaccination acceptance. Considering the potential detrimental impact of pandemic fatigue on adherence to preventive measures, including vaccination, regular assessment of fatigue and appropriate interventions are warranted after nearly 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Increasing individual and social risk perception, strengthening institutional trust and enhancing prosocial attitudes may increase the acceptance of the measures which, in turn, could lead to stronger adherence to recommended preventive measures, including accepting vaccination.Citation43

Finally, our findings suggested that we need tailored education messages for the general public to address the concerns about the side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine booster that would dispel the misconceptions about its risks and side effects. As is also evident in the present study, a higher experience of severe side effects from the primary vaccination was associated with a higher level of booster vaccination hesitancy. To date, adverse events following immunization (AEFI) among COVID-19 vaccine recipients in Malaysia have been rare. As of 11 March 2022, only 379 AEFI were reported in one million COVID-19 vaccine doses administered.Citation44 Therefore, public health communication should address the public’s anxiety about AEFI and emphasize that the post-vaccination side effects for the third dose of COVID-19 vaccine are mild to moderate for most recipients, similar to the side effects following the first two doses.

In interpreting the results of this study, some limitations need to be considered. The first limitation is the cross-sectional design: we identified associations but could not infer cause and effect. Second, self-selection bias is another major limitation of online survey research and advertising of questionnaire using social network platform: there are undoubtedly some individuals who are more likely than others to complete an online survey.Citation45 As evident, our study respondents were mostly healthy young adults; therefore, results may not be generalizable to the wider community. Further, there is also the issue regarding self-reporting bias in an online survey, which may represent a key problem in the validity of the assessment. The tendency to report socially desirable responses may potentially lead to falsely reporting one’s willingness to get vaccinated. The findings of this study should be interpreted in light of the above-mentioned limitations. Also of important highlight, unlike other studies, our study used a wider scale, which in general provides a better reflection of respondents’ true evaluation, in assessing willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine booster. Therefore, comparisons with other studies that used an absolute willingness and unwillingness scale may not be possible. It is also important to note that many factors are associated with COVID-19 vaccine booster resistance and hesitancy that are not investigated in this study. Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings contribute tremendously to our understanding of public responses to the new COVID-19 booster-dose program in Malaysia.

Conclusion

Despite a generally high willingness to receive a booster dose of a COVID-19 vaccine among the Malaysian public, a small percentage of reported hesitating or refusing the booster dose may likely pose a threat to effective prevention and control of the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of this study indicate that substantial socioeconomic status, ethnicity and inter-regional differences exist in the willingness to receive the COVID-19 booster vaccination. This study also identified the determinants of hesitation in individual intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster; there are a range of factors that predict COVID-19 booster intentions—including experience of side effects in the past COVID-19 vaccination, pandemic fatigue and fear of side effects of the booster vaccination, as well as the uncertain long-term safety of multiple COVID-19 vaccinations. Public health communication message should be tailored specifically to address the identified factors associated with hesitancy in the administration of COVID-19 vaccine booster.

Authors’ contribution

Li Ping Wong, Yulan Lin and Zhijian Hu contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by Haridah Alias, Yan Li Siaw, Mustakiza Muslimin and Lee Lee Lai. Data analysis was performed by Li Ping Wong and Haridah Alias. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Li Ping Wong and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Levin EG, Lustig Y, Cohen C, Fluss R, Indenbaum V, Amit S, Doolman R, Asraf K, Mendelson E, Ziv A, et al. Waning immune humoral response to BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine over 6 months. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(24):e84. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2114583.

- Naaber P, Tserel L, Kangro K, Sepp E, Jürjenson V, Adamson A, Haljasmägi L, Rumm AP, Maruste R, Kärner J, et al. Dynamics of antibody response to BNT162b2 vaccine after six months: a longitudinal prospective study. Lancet. 2021;10:100208. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100208.

- Altmann DM, Boyton RJ. Waning immunity to SARS-CoV-2: implications for vaccine booster strategies. Lancet. 2021;9:1356–9. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00458-6.

- Mohapatra RJ, El-Shall NA, Tiwari R, Nainu F, Ramana KV, Sarangi AK, Mohamed TA, Designu PA, Chakraborty C, Dhama K. 2022. Need of booster vaccine doses to counteract the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants in the context of the Omicron variant and increasing COVID-19 cases: an update. Hum Vaccines Immunother. [Under publication].

- Omer SB, Malani PN. Booster vaccination to prevent COVID-19 in the era of omicron: an effective part of a layered public health approach. JAMA. 2022;327(7):628–29. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.0892.

- Wald A. Booster vaccination to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission and infection. JAMA. 2022;327(4):327–28. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.23726.

- Munro AP, Janani L, Cornelius V, Aley PK, Babbage G, Baxter D, Bula M, Cathie K, Chatterjee K, Dodd K, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of seven COVID-19 vaccines as a third dose (booster) following two doses of ChAdox1 nCov-19 or BNT162b2 in the UK (COV-BOOST): a blinded, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10318):2258–76. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02717-3.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. Current population estimates Malaysia. 2021 July 15 [accessed 2022 Mar 12]. https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=155&bul_id=ZjJOSnpJR21sQWVUcUp6ODRudm5JZz09&menu_id=L0pheU43NWJwRWVSZklWdzQ4TlhUUT09 .

- WHO. Malaysia Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report weekly report for the week ending. 2021 Mar 28 [accessed 2022 Mar 12]. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/wpro-documents/countries/malaysia/coronavirus-disease-%28covid-19%29-situation-reports-in-malaysia/covid19_sitrep_mys_20210328_final.pdf?sfvrsn=7957aad9_4&download=true .

- Dasgupta S. Independent. Malaysia government tells those who choose not to get Covid vaccine: ‘We will make life very difficult. 2021 Oct 18 [accessed 2022 Apr 21]. https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/southeast-asia/covid-malaysia-unvaccinated-health-ministry-b1940110.html .

- COVIDNOW. Vaccinations in Malaysia. 2022 Mar 16 [accessed 2022Mar 12]. https://covidnow.moh.gov.my/vaccinations/ .

- Wong LP, Alias H, Danaee M, Ahmed J, Lachyan A, Cai CZ, Lin Y, Hu Z, Tan SY, Lu Y, et al. COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine characteristics influencing vaccination acceptance: a global survey of 17 countries. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10(1):122. doi:10.1186/s40249-021-00900-w.

- Lau JF, Woon YL, Leong CT, Teh HS. Factors influencing acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine in Malaysia: a web-based survey. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2021;12(6):361–73. doi:10.24171/j.phrp.2021.0085.

- Syed Alwi SA, Rafidah E, Zurraini A, Juslina O, Brohi IB, Lukas S. A survey on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and concern among Malaysians. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1129. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11071-6.

- Wong LP, Alias H, Wong PF, Lee HY, AbuBakar S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2020;16(9):2204–14. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1790279.

- WHO Europe. Pandemic fatigue. Reinvigorating the public to prevent COVID-19. 2020 [accessed 2022 Mar 12]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/335820/WHO-EURO-2020-1160-40906-55390-eng.pdf .

- Reicher S, Drury J. Pandemic fatigue? How adherence to covid-19 regulations has been misrepresented and why it matters. BMJ. 2021;372(n137). doi:10.1136/bmj.n137.

- Lindholt MF, Jørgensen F, Bor A, Petersen MB. Public acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines: cross-national evidence on levels and individual-level predictors using observational data. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6):e048172. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048172.

- Ala’a B, Tarhini Z, Akour A. A swaying between successive pandemic waves and pandemic fatigue: where does Jordan stand? Ann Med Surg. 2021;65:102298. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102298.

- Wolff K. COVID-19 vaccination intentions: the theory of planned behavior, optimistic bias, and anticipated regret. Front Psychol. 2021;12:648289. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648289.

- Thaker J, Ganchoudhuri S. The role of attitudes, norms, and efficacy on shifting COVID-19 vaccine intentions: a longitudinal study of COVID-19 vaccination intentions in New Zealand. Vaccines. 2021;9(10):1132. doi:10.3390/vaccines9101132.

- Shmueli L. Predicting intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine among the general population using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–3. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10816-7.

- Zhang KC, Fang Y, Cao H, Chen H, Hu T, Chen Y, Zhou X, Wang Z. Behavioral intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese factory workers: cross-sectional online survey. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(3):e24673. doi:10.2196/24673.

- Cerda AA, García LY. Hesitation and refusal factors in individuals’ decision-making processes regarding a coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination. Front Public Health. 2021;9:9. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.626852.

- Norhayati MN, Yusof RC, Azman YM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance. Front Med. 2021:8. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.783982.

- Raosoft. Sample size calculator by Raosoft. 2017 [accessed 2021 Aug 18]. http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html .

- Daniel WW. Biostatistics: a foundation for analysis in the health sciences. 7th ed. New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons; 1999.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. Launching of report on the key findings population and housing census of Malaysia 2020. 2022Feb 14 [accessed 2022 Mar 13]. https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=117&bul_id=akliVWdIa2g3Y2VubTVSMkxmYXp1UT09&menu_id=L0pheU43NWJwRWVSZklWdzQ4TlhUUT09 .

- Wejnert C, Pham H, Krishna N, Le B, DiNenno E. Estimating design effect and calculating sample size for respondent-driven sampling studies of injection drug users in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(4):797–806. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0147-8.

- Lilleholt L, Zettler I, Betsch C, Böhm R. 2020. Pandemic fatigue: measurement, correlates, and consequences. Psy Arvix. [ Preprint].

- MySejahtera. Introduction. 2021 [accessed 2022 Apr 21]. https://mysejahtera.malaysia.gov.my/intro_en/ .

- Al-Qerem W, Al Bawab AQ, Hammad A, Ling J, Alasmari F. Willingness of the Jordanian population to receive a COVID-19 booster dose: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2022;10(3):410. doi:10.3390/vaccines10030410.

- Yadete T, Batra K, Netski DM, Antonio S, Patros MJ, Bester JC. Assessing acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine booster dose among adult Americans: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021;9(12):1424. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121424.

- Rzymski P, Poniedziałek B, Fal A. Willingness to receive the booster COVID-19 vaccine dose in Poland. Vaccines. 2021;9(11):1286. doi:10.3390/vaccines9111286.

- Tung TH, Lin XQ, Chen Y, Zhang MX, Zhu JS. Willingness to receive a booster dose of inactivated coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine in Taizhou, China. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021. doi:10.1080/14760584.2022.2016401.

- Daud S. The COVID-19 pandemic crisis in Malaysia and the social protection program. J Dev Soc. 2021;37:480–501. doi:10.1177/0169796X211041154.

- Chen JA, Zhang E, Liu CH. Potential impact of COVID-19–related racial discrimination on the health of Asian Americans. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(11):1624–27. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305858.

- Gruer L, Agyemang C, Bhopal R, Chiarenza A, Krasnik A, Kumar B Migration, ethnicity, racism and the COVID-19 pandemic: a conference marking the launch of a new global society. Public Health Pract (Oxf). 2021;2:100088. doi:10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100088.

- Mohamed NA, Solehan HM, Mohd Rani MD, Ithnin M, Che Isahak CI, Sobh E. Knowledge, acceptance and perception on COVID-19 vaccine among Malaysians: a web-based survey. Plos One. 2021;16(8):e0256110. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0256110.

- Din HM, Adnan RN, Akahbar SA, Ahmad SA. Characteristics of COVID-19-related deaths among older adults in Malaysia. Malays J Med Sci. 2021;28(4):138–45. doi:10.21315/mjms2021.28.4.14.

- Wong LP, Alias H, Tan YR, Tan KM. Older people and responses to COVID‐19: a cross‐sectional study of prevention practices and vaccination intention. Int J Older People Nurs. 2021:e12436. doi:10.1111/opn.12436.

- Mattiuzzi C, Lippi G. Efficacy of COVID-19 vaccine booster doses in older people. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022;13(1):275–78. doi:10.1007/s41999-022-00615-7.

- Petherick A, Goldszmidt R, Andrade EB, Furst R, Hale T, Pott A, Wood A. A worldwide assessment of changes in adherence to COVID-19 protective behaviours and hypothesized pandemic fatigue. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5:1145–60. doi:10.1038/s41562-021-01181-x.

- Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia. Status Laporan Kesan Advers Susulan Imunisasi (AEFI) Vaksin Covid-19 Sehingga 11/03/2022. 2022 Mar 16 [accessed 2022 Mar 14]. https://covid-19.moh.gov.my/semasa-kkm/2022/03/status-laporan-kesan-advers-susulan-imunisasi-aefi-vaksin-covid-19-sehingga-11-03-2022 .

- Wright KB. Researching internet-based populations: advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. JCMC 2005;10:1034. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00259.x .