ABSTRACT

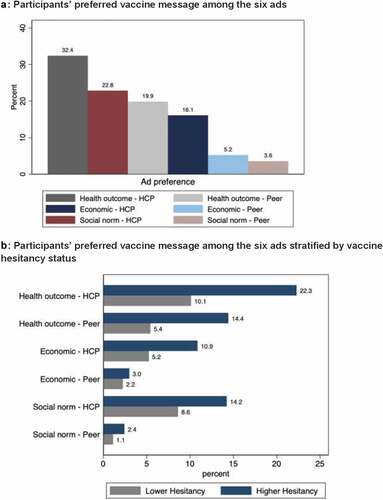

Few studies have examined the relationships between the different aspects of vaccination communication and vaccine attitudes. We aimed to evaluate the influence of three unique messaging appeal framings of vaccination from two types of messengers on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in India. We surveyed 534 online participants in India using Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) from December 2021 through January 2022. We assessed participants’ perception of three messaging appeals of vaccination – COVID-19 disease health outcomes, social norms related to vaccination, and economic impact of COVID-19 - from two messengers, healthcare providers (HCP) and peers. Using a multivariable multinomial logistic regression, we examined participants’ ad preference and vaccine hesitancy. Participants expressed a high level of approval for all of the ads, with >80% positive responses for all questions across ads. Overall ads delivered by health care workers were preferred by a majority of participants in our study (n = 381, 71.4%). Ad preference ranged from 3.6% (n = 19) social norm/peer ad to 32.4% (n = 173) health outcome/HCP ad and half of participants preferred the health outcome ad (n = 279, 52.3%). Additionally, vaccine hesitancy was not related to preference (p = .513): HCP vs. peer ads (p = .522); message type (p = .284). The results suggest that all three appeals tested were generally acceptable, as well as the two messenger types, although preference was for the health care provider messenger and health outcome appeal. Individuals are motivated and influenced by a multitude of factors, requiring vaccine messaging that is persuasive, salient, and induces contextually relevant action.

Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy – the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite availability of vaccines – has impacted efforts to control the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic in many populations. Hesitancy for COVID-19 vaccination, as with other vaccines, is complex, context-specific, and dependent upon multiple influences.Citation1,Citation2 Misinformation and disinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic have increasingly spread through social media platforms and impact vaccine uptake.Citation3 Vaccine hesitancy has been linked to outbreaks of vaccine preventable disease; and, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is strong evidence that unvaccinated individuals are at much higher risk of severe outcomes.Citation4

Many communication approaches have been proposed to address vaccine hesitancy. Broadly, approaches include dialogue-based, reminder/recall, and multi-component approaches, among others.Citation1,Citation5 A systematic review of peer-reviewed literature found that the most effective strategies were dialogue-based and multi-component and tailored to the target population’s reason for hesitancy.Citation6 A recent review found that communication interventions targeted at vaccine hesitancy outcomes have utilized a diverse range of message appeals, approaches, and messengers. These studies were largely conducted in high-income settings and focused on few vaccines (e.g., HPV, influenza, and MMR) and multi-component interventions – with varied combinations of appeal, approach, and messenger strategies.Citation7

Health communication strategies utilize a core appeal to attract recipients’ attention, and an appeal serves as a guide for what to focus on in a message. The approach to delivery of the message, such as storytelling or tailoring, serves to convey the message in a compelling manner. A review reported that interventions using approaches tailored to behavior change constructs (e.g., risk perception or self-efficacy), tailored personal narratives, and peer approaches (e.g., peer education) that utilize community norms were effective approaches to address concerns and increase vaccine acceptance.Citation7 Beyond the appeal and delivery approach, the messenger can also strongly impact the effectiveness of the message. Previous evidence has shown that one of the strongest drivers of maternal and childhood vaccine acceptance is the recommendation of a healthcare professional.Citation8

Vaccine hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines is a substantial issue in India. According to a recent nationwide survey from 27 states and union territories, 70% of the Indian population has some form of hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine, with many unsure if they will get the vaccine.Citation9 Regarding vaccination and vaccine hesitancy generally in India, a large study among caregivers (n = 38,209) of under-vaccinated children summarized reasons for missing vaccination, finding mostly individual-level factors as leading reasons for missing vaccination, including lack of awareness (45%), vaccine hesitancy/refusal related to fear of adverse events following immunizations (AEFIs) (24%), vaccine hesitancy/refusal other than fear of AEFIs (11%), child traveling (i.e., the child is not at home or in town to receive the vaccine) (8%), operational gaps (4%), and other factors (9%).Citation10

Effective strategies to encourage COVID-19 vaccination uptake must consider how different aspects of health communication can be tailored to specific contexts. Evidence indicates that health communication vaccine messaging can affect attitudes and subsequent behaviors. As a result, it is critical that messaging is persuasive.Citation11 To address this research gap, our study aimed to evaluate the influence of three specific messaging appeal framings – COVID-19 disease health outcomes, social norms related to vaccination, and economic impact of COVID-19 - of vaccination from two kinds of messengers, healthcare providers and peers, on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in India. We conducted a scoping literature review to identify appeals and messenger types that might be effective in affecting vaccine intentions.

Methods

We conducted an online survey of participants in India from December 2021 through January 2022 using Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk), a crowdsourcing marketplace for users to complete short tasks, such as surveys or short experiments, for a fee.Citation12 Related to validity, Thomas and CliffordCitation13 evaluated the validity of mTurk exclusion methods and found that with multiple, rigorous attention checks and screening methods, validity from mTurk data is comparable to data obtained from lab or field experiments.

Like other crowdsourcing platforms commonly used in academic survey research, only mTurk users who meet pre-determined inclusion criteria can see the option to opt-in to responding to the survey. Eligible survey participants can see the title and a short description of the task along with an estimated time length for task completion and any renumeration. The survey was described as “Answer a survey about COVID-19 vaccine messaging” with an estimated duration of up to 30 minutes and renumeration of $3 for completion.

Inclusion criteria for mTurk participants was at least 18 years of age, currently living in India, with a mTurk Human Intelligence Tasks (HIT) Approval Rate of 95% or higher; only users meeting these criteria could see and choose to respond to the survey. The HIT approval rate in mTurk shows the percent of prior tasks submitted by an mTurk user that were accepted as “complete” by those posting the task.Citation14 This score is used as a measure of participant quality and a 95% or higher rating is recommended as it has been found to provide higher quality responses.Citation15,Citation16

Between 13 December 2021, and 21 January 2022, we received 834 survey responses, of which 534 met our inclusion criteria for analysis. To ensure high-quality results, we followed recommendations for best practices in high quality mTurk data collection by excluding responses from the analysis if there were indications of poor attention or automated non-human robotic responders (“bots”).Citation12–15–Citation17

We utilized three strategies in the survey to ensure respondents were reading survey questions and providing quality responses. First, we presented participants with this question: “It is important for this survey that you read the questions before answering. Please select ‘Somewhat Agree.’” Respondents who did not answer correctly were automatically disqualified from the rest of the survey. Second, we excluded responses from participants who completed the survey in less than five minutes to avoid inattentive responses. The estimated time to complete the survey based on SurveyMonkey’s guidance on average time spent per question was approximately 14 minutes for this survey. Considering that many survey participants may not be native English speakers, we described the survey as taking up to 30 minutes to allow for thorough reading comprehension and response time. Prior research on mTurk data quality has found that practiced survey responders can complete surveys in quicker times compared to naïve participants. A pilot test of the survey with 10 mTurk users in India, not included in this analysis, found that on average participants completed the survey in 16 minutes (responses ranged from 23 minutes to 5 minutes) with 5 minutes as the shortest time where quality answers were provided. Third, we required participants to write-in their country of residence as a question and those responding with any country outside of India were excluded.

Survey items

The survey included 54 questions (Appendix A). It included socio-demographic questions, including age (18–24, 25–39, 40–64, 65+), gender (male, female, other, prefer not to say), level of education (secondary or high school, bachelor’s degree or 4-year college degree, graduate level degree, or other), and pregnancy status if applicable (yes, no, non-applicable).

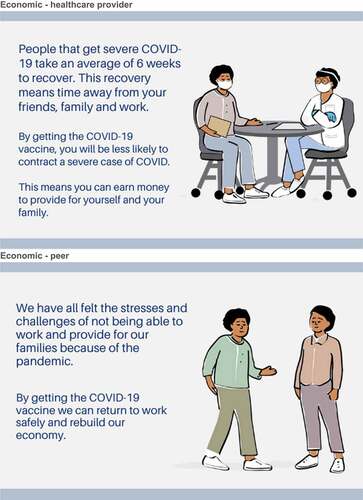

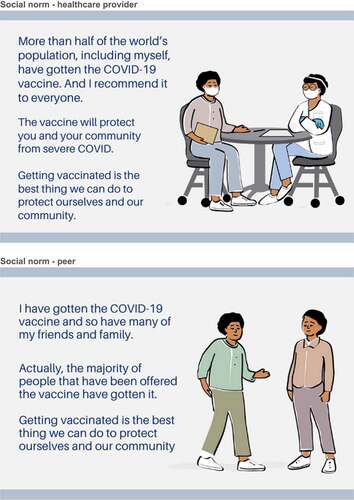

Each participant viewed six ads, which were broadly composed of two elements: messenger and appeal (Appendix B). The messengers included a healthcare provider image, which depicts a medical provider talking to a patient, and a peer image, which depicts two people, peers, speaking to each other. We included the following appeals: health outcome, which focused on the risk of COVID-19 disease and the protective effect of vaccination against disease; economic benefit, which focused on loss of work time and income due to COVID-19 infection and the protective effect of vaccination against economic loss; and social norms, which focused on how most people have received the COVID-19 vaccine and the protective effect of vaccination for the community. These appeals were chosen after we conducted a scoping literature review to identify potential messengers and appeals (manuscript under review). The review examined various appeals and messengers used in vaccine communication experiments that were evaluated for their ability to change vaccine attitudes or vaccine behaviors.

After each ad, six questions covering participant level of agreement specific to each ad were asked, including relevance (Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was relevant to me), motivation to get the COVID-19 vaccine (Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine), motivation to get COVID-19 vaccination for their child (if applicable) (Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine for my child under 18 years of age), if the ad was designed for someone like the participant (Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was designed for people like me), and if the ad would prompt the participant to tell someone about the COVID-19 vaccine (Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad would prompt me to tell someone about the COVID-19 vaccine). Participants were also asked to indicate which ad of the six would motivate them the most to get the COVID-19 vaccine (Which ad motivates you most to get the COVID-19 vaccine?).

Three questions were used to assess participant vaccine hesitancy. Participants were asked if they had ever delayed getting a recommended vaccine through a yes/no response (Have you ever delayed getting a recommended vaccine or decided not to get a recommended vaccine for reasons other than illness or allergy?). Two questions asked participants about their level of agreement related to COVID-19 vaccine safety concern (How concerned are you that a COVID-19 vaccine might not be safe?), and participant perception of vaccine effectiveness (How concerned are you that a COVID-19 vaccine might not prevent the disease?).

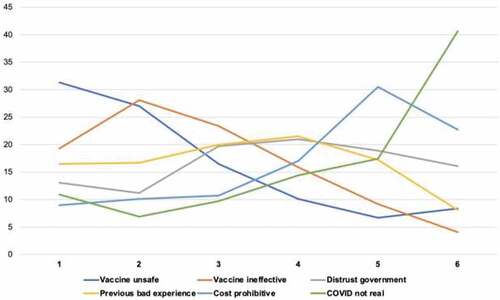

To further examine the reason why an individual may not want to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, participants were asked to rank six statements based on level of concern, with one being the most concerning, to six being the least concerning (There are multiple reasons why someone may not want to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Please rank these reasons in order, with 1 being the most concerning, to 6 being the least concerning.). Concerns included safety (I do not feel the vaccine is safe), vaccine effectiveness (I do not feel the vaccine is effective), trust in government (I do not trust the government), vaccine experience (People I know have not had a good experience getting the vaccine), and cost (It is cost prohibitive for me to get the vaccine), and belief in the existence of COVID (I believe COVID-19 is not real). An additional open-ended question was included to explore the influence of political ideology (Think of the political parties in your country. Which one is most representative of your views?).

Sample size

We determined our sample size based upon calculation of confidence interval width around an expected sample proportion of vaccine hesitancy in the study population.Citation18,Citation19 A sample size of 500 participants will yield two-sided 95% confidence intervals with a width of 0.053 (0.070, 0.123) for prevalence of vaccine hesitancy of 10% and a width of 0.089 (0.459, 0.549) for prevalence of vaccine hesitancy of 50%.

Statistical analysis

We summarized participant characteristics overall and stratified by binary vaccine hesitancy status groups and assessed differences between these groups using chi-squared tests. We collapsed ad preference responses into binary variables (strongly agree/agree vs. strongly disagree/disagree) and examined the proportion responding positively across constructs for each ad. Variables for some participant characteristics were collapsed due to small numbers in some categories, including age (collapsed to <40, ≥40 levels for regression models), gender (female and male levels used for regression models as the “Prefer not to say” option had only n = 1 observation).

We examined ad preference by asking participants which ad they most preferred using multivariable multinomial logistic regression. We estimated relative risks and 95% confidence intervals using ad 1 as the reference group (Health Outcome – Healthcare Provider ad) and a binary variable for vaccine hesitancy as our primary characteristic of interest. To clearly describe participant’s ad type preference independently of the messenger, we stratified participants by those who preferred ads delivered by healthcare providers or peers. We then assessed the relationships between ad type preference and participant characteristics in separate multivariable multinomial models. Included in models were participant characteristic data known from the literature to be associated with vaccine attitudes, including age and gender.Citation20–22 We constructed an ordinal scale from 0 to 3 to describe participants’ level of vaccine hesitancy by assigning 1 point for each of three yes/no questions. We then examined the distribution of scores and established a cutoff to stratify participants into two groups (0–1 and 2–3), which we defined as lower hesitancy and higher hesitancy. Statistical analysis was performed in Stata 16.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). The study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Results

A total of 834 participants responded to the survey (). We excluded participants for the following data quality checks: survey completion <5 minutes (n = 234, 28.1%) and failed attention check (n = 29, 3.5%). We also excluded participants for reporting a residence outside of India (n = 24, 2.9%) and incomplete survey response (n = 13, 1.6%). describes the 534 study participants available for analysis. The majority of participants were 24–39 years old (n = 448, 83.9%), male (n = 362, 67.9%), and had a bachelor’s degree or graduate degree (n = 517, 97.5%). A third of female participants reported being pregnant (n = 56/171, 32.8%).

Table 1. Participant characteristics and prevalence of vaccine hesitancy (n = 534).

Nearly all participants (n = 511, 96.2%) reported being vaccinated against COVID-19. More than a quarter (n = 145, 27.7%) reported having ever delayed or refused a recommended vaccination. Most participants were at least slightly concerned that the vaccine might not prevent COVID-19 disease (n = 430, 80.5%) or might not be safe (n = 378, 70.8%). Safety concerns were higher when asked about the vaccine for pregnant women (n = 458, 85.8%) and children under age 18 (n = 470, 88.0%).

Few participants had a score of 0 on our vaccine hesitancy scale (n = 73, 13.7%). The vaccine hesitancy scale distribution across the three questions for the remaining participants was 1 (n = 102, 19.1%), 2 (n = 226, 42.3%), and 3 (n = 133, 24.9%). We categorized participants as lower hesitancy (0 or 1 concerns) (n = 175, 32.8%) and higher hesitancy (2 or 3 concerns) (n = 359, 67.2%).

In bivariate analyses, of the demographic characteristics (age, gender, education, pregnancy status), only age was significantly associated with vaccine hesitancy status. The proportion of participants with higher hesitancy was highest among the 24–39 age group (n = 323, 72.1%) vs. the 18–24 (n = 10, 38.5%) and 40+ (n = 26, 43.3%) groups. In a multivariable logistic regression model, participants who were 24–39 (aOR: 4.91, 95% CI: 2.13, 11.3) were more likely to have higher vaccine hesitancy status and men were less likely to have higher hesitancy status, although this did not reach statistical significance (aOR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.45, 1.04, (p = .072)) (Appendix C).

Participant responses were nearly universally positive for each question about ad preference: “I agree with the message provided in this ad” (92.1% to 97.6%)), the “ad was designed for me” (87.3% to 94.4%), the “ad was relevant to me” (89.5% to 95.7%), “the ad would prompt me to tell someone else about the COVID-19 vaccine” (91.4% to 96.6%), the “ad motivates me to get the vaccine” (92.1% to 97.8%), and the “ad motivates me to get a vaccine for children under age 18” (81.5% to 88.1%) ().

Table 2. Participant preferences for message aspects across six ads.

Participant responses to the question, “Which ad would motivate you most to get the COVID-19 vaccine?” ranged from 3.6% (n = 19) for the social norm/peer ad to 32.4% (n = 173) for the health outcome/healthcare provider ad (). Half of participants preferred the health outcome ad (n = 279, 52.3%), delivered either by a healthcare provider (n = 173, 62.0%) or peer (n = 106, 38.0%). Previous studies indicate a similar influence of peers as a key determinant of vaccine uptake. Knowledge of peers who have received the COVID-19 vaccine have been associated with higher COVID-19 vaccine uptake.Citation23,Citation24 The other half of participants largely preferred the healthcare provider delivered ads with the economic message (n = 86, 75.4%) and social norm message (122, 86.5%). More than two-thirds of participants (n = 381, 71.4%) had a preference for the healthcare provider ads over the peer ads (n = 153, 28.7%). Vaccine hesitancy status was not related to preference for the six ads (p = .513), healthcare provider vs. peer ads (p = .522), nor message type (p = .284).

We ranked vaccine concerns from highest to lowest level of concern (). We stratified multivariable multinomial models by healthcare provider and peer ads (). In the healthcare provider ad model, older individuals (40+) were less likely to prefer the social norm ad vs. health outcome ad (aRR 0.30, 95% CI: 0.12, 0.73). However, in the peer ad model, older individuals (40+) were more likely to prefer the social norm ad vs. health outcome ad (aRR 5.41, 95% CI: 1.43, 20.38). There were no differences in ad preference by vaccine hesitancy status.

Table 3. Relative risk ratios of ad preference by vaccine hesitancy status and participant characteristics using multivariable multinomial logistic regression modeling.

Discussion

We conducted an online survey of participants in India to understand preferences for ads framed around health outcome, economic, or social norm messages and delivered by either a healthcare provider or peer messenger. Our study population was homogeneous and skewed to ages 24–39, male, highly-educated individuals. Participants also had a higher level of vaccination than the general population in India (95% vs. 57%); despite this, many (35%) expressed concerns about vaccine safety, effectiveness, or both.Citation25,Citation26 Vaccine safety was the most pressing concern, followed by the perception that the vaccine was ineffective, and previous negative experience with vaccines. This indicates that while a substantial proportion of individuals have received the vaccine, concerns remain, suggesting there is a need to develop tailored communication approaches to increase vaccine confidence.

Participants expressed a high level of approval for all of the ads they viewed, with >80% positive response for all questions across ads by message type and messenger. This suggests that all three appeals tested were generally acceptable, as well as the two messenger types. While the elements tested in this study were all acceptable, future work should test additional appeals and messengers to examine if there are specific appeals and messengers are more persuasive among specific target populations.

Overall, ads delivered by healthcare providers were preferred by a majority of participants in our study. While trust in healthcare providers has been declining due to the broad erosion of trust in healthcare systems in some settings during the pandemic, healthcare providers remain a critical trusted source of health information, including vaccine information.Citation27 The pandemic has illustrated the importance of continuing to build a foundation of trust between the public and the healthcare system generally.Citation28 The pandemic has also taught us the importance of peer influence, given the ubiquitous nature of peer-to-peer information exchange on social media platforms, and, as such, it is imperative to nurture peer ambassador approaches as another avenue to increase vaccine acceptance.Citation29,Citation30 Additionally, there is a need to identify other crucial messengers that hold the trust of the community.Citation31,Citation32

More than half of participants in our study preferred the health outcome ad, followed by the social norm and economic ad appeals. Appeals focused on health outcomes have been shown to increase the salience of a disease threat in some contexts.Citation33 A United States online survey that, similar to our study, evaluated health outcome, economic, and social norm frames, using a healthcare provider and peer messengers, found that the messages using personal health risks increased respondents’ intention to vaccinate, irrespective of message source.Citation11 The effect of the health outcome frame may be most impactful when the health outcome information is tailored to specific recipients. For example, obstetrician gynecologists reported that framing health outcome message appeals around the potential risk of vaccine-preventable diseases present to the fetus or newborn was perceived by providers as the most effective strategy to improve vaccine uptake among pregnant women.Citation34 Social norms and attitudes also act as strong determinants of vaccine intentions and behaviors.Citation35 Several studies have demonstrated the importance of social norms in affecting COVID-19 attitudes and intentions.Citation35,Citation36 Although in some contexts, for example among an online population of young people, messages based upon norms were not more effective than standard health outcome and benefits of vaccination framing.Citation37 A social norms approach was also shown as effective in correcting misinformation and reducing beliefs in conspiracy theories.Citation38 There is also evidence prior to the pandemic, that the influence of social norms such as the higher perceived levels of approval of vaccination from close family and friends can be a strong predictor of intentions for other vaccines.Citation39 Economic framing, and as well as monetary incentives have been shown to be successful motivators for vaccine uptake, including COVID-19 vaccination.Citation40,Citation41 However, in a US online survey, messages about economic costs, such as risk of job loss, had no effect on vaccine intention.Citation11 The economic ad was the least preferred of the three frames in our study as well. This may be because of the ad choices presented, as although it was least preferred, this was relative to the health outcome and social norms frames. Perhaps health outcomes frames, which includes mortality along with morbidity, are more persuasive than economic losses. Related to the social norms frame, in times of uncertainty such as the pandemic, individuals heavily rely on peer influence to inform their own decision-making. This may be why the social norms frame was preferred more than the economic frame.Citation42

The study had several limitations. The primary limitation is that the study population was not representative of all of India’s population of more than 1 billion individuals. This survey was conducted online and in English, and although this is one of India’s official languages, it is spoken in only certain regions and demographic sub-populations. The purpose of this survey was to add to the knowledge of responses to vaccine messaging in an online context, and thus may only reflect the preferences of the estimated 43% of India’s population that uses the internet.Citation43 Further, convenience samples such as those from mTurk may differ from national probability samples. Boas, Christenson, and Glick (2018) completed a 7,300 respondent comparison of online convenience samples recruited from Facebook, MTurk, and Qualtrics to nationally representative benchmarks in India and the United States.Citation44 Boas, Christenson, and Glick found that mTurk respondents in India were younger (average age 32), more educated, higher income, more likely to be male, less likely to be married, and had a smaller share of lower-caste members compared to nationally representative benchmarks.Citation44 We saw strong evidence of this bias in our sample, which had lower levels of participants who were older or had less education. There are likely other factors that could have affected ad preferences that were not captured. The potential effect is difficult to quantify, in either direction or magnitude, and may limit the generalizability of our results. There were participant characteristics associated with vaccine attitudes for which we did not collect data due to survey length limitations. These potential confounders – including geographical region, income, and other sociodemographic and cultural factors – were uncontrolled in our analyses and likely affect the associations we explored in this study. Lastly, the study did not have a control group, preventing comparisons for questions about vaccine attitudes between participants who viewed specific ads vs. those who viewed none.

Despite these limitations, our study is among one of the first to test various appeals and messengers for vaccine acceptance. It is clear that individuals are motivated by different factors, influenced by different information sources, and assess risks and benefits differently. Given the substantial morbidity and mortality that COVID-19 has exacted upon India specifically and the world generally, it will be even more crucial to ensure that vaccine messaging is persuasive, salient, and induces action. We believe the results of our study is one step toward this overall goal for more effective messaging, and we hope that health communicators will be able to take these results and continue to build the evidence base for persuasive messaging for vaccine acceptance.

Consent to participate

Consent was obtained from participants before the start of the questionnaire.

Ethics approval

This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (Baltimore, USA).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):1–13. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Solís Arce JS, Warren SS, Meriggi NF, Scacco A, McMurry N, Voors M, Syunyaev G, Malik AA, Aboutajdine S, Adeojo O, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Med. 2021;27(8):1385–1394. Epub 2021 Jul 16. PMID: 34272499; PMCID: PMC8363502. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01454-y.

- Pullan S, Dey M. Vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccination in the time of COVID-19: a google trends analysis. Vaccine. 2021;39(14):1877–1881. Epub 2021 Mar 6. PMID: 33715904; PMCID: PMC7936546. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.019.

- Tenforde MW, Self WH, Adams K, Gaglani M, Ginde AA, McNeal T, Patel MM, Douin DJ, Talbot HK, Casey JD. Association between mRNA vaccination and COVID-19 hospitalization and disease severity. Jama. 2021;326(20):2043–2054. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.19499.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, MacDonald NE. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4191–4203. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.041.

- Jarrett C, Wilson R, O’-Leary M, Eckersberger E, Larson HJ. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy – a systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4180–4190. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.040.

- Limaye RJ, Holroyd TA, Blunt M, Jamison AF, Sauer M, Weeks R, Wahl B, Christenson K, Smith C, Minchin J, et al. Social media strategies to affect vaccine acceptance: a systematic literature review. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021;20(8):959–973. doi:10.1080/14760584.2021.1949292.

- Lutz CS, Carr W, Cohn A, Rodriguez L. Understanding barriers and predictors of maternal immunization: identifying gaps through an exploratory literature review. Vaccine. 2018;36(49):7445–7455. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.046.

- Chandani S, Jani D, Sahu PK, Kataria U, Suryawanshi S, Khubchandani J, Thorat S, Chitlange S, Sharma D. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in India: state of the nation and priorities for research. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;18:100375. doi:10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100375.

- Gurani V, Haldar P, Aggarwal MK, Das MK, Chauhan A, Murray J, Arora NK, Jhalani M, Sudan P. Improving vaccination coverage in India: lessons from intensified mission indradhanush, a cross-sectoral systems strengthening strategy. Bmj. 2018;363:k4782. doi:10.1136/bmj.k4782.

- Motta M, Sylvester S, Callaghan T, Lunz-Trujillo K. Encouraging COVID-19 vaccine uptake through effective health communication. Front Polit Sci. 2021;3:1. doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.630133.

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s mechanical turk: a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality data? In: Kazdin AE, editor. Methodological issues and strategies in clinical research. American Psychological Association; 2016. p. 133–139. doi:10.1037/14805-009.

- Thomas KA, Clifford S. Validity and mechanical turk: an assessment of exclusion methods and interactive experiments. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;77:184–197. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.038.

- Berinsky AJ, Huber GA, Lenz GS. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.Com’s mechanical turk. Polit Anal. 2012;20(3):351–368. doi:10.1093/pan/mpr057.

- Vosgerau J, Acquisti A. Reputation as a sufficient condition for data quality on amazon mechanical turk. Behav Res Methods. 2014;46(4):1023–1031. doi:10.3758/s13428-013-0434-y.

- Matherly T. A panel for lemons? Positivity bias, reputation systems and data quality on mturk. Eur J Mark. 2019;53(2):195–223. doi:10.1108/EJM-07-2017-0491.

- O’-Brochta W, Parikh S. Anomalous responses on amazon mechanical turk: an Indian perspective. Res Politics. 2021;8(2):20531680211016972. doi:10.1177/20531680211016971.

- Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 3rd ed. New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons; 2003.

- Newcombe RG. Two-Sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17(8):857–872. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857:aid-sim777>3.0.co;2-e.

- Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines. 2020;8(3):482. doi:10.3390/vaccines8030482.

- Sethi S, Kumar A, Mandal A, Shaikh M, Hall CA, Kirk JMW, Moss P, Brookes MJ, Basu S. The UPTAKE study: implications for the future of COVID-19 vaccination trial recruitment in UK and beyond. Trials. 2021;22(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s13063-021-05250-4.

- Francis MR, Nohynek H, Larson H, Balraj V, Mohan VR, Kang G, Nuorti JP. Factors associated with routine childhood vaccine uptake and reasons for non-vaccination in India: 1998–2008. Vaccine. 2020;36(44):6559–6566. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.026.

- Singh A, Lai AHY, Wang J, Asim S, Chan P-S-F, Wang Z, Yeoh EK. Multilevel determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among south Asian ethnic minorities in Hong Kong: cross-sectional web-based survey. JMIR Public Health Surveillance. 2021;7(11):e31707. doi:10.2196/31707.

- Verelst F, Willem L, Kessels R, Beutels P. Individual decisions to vaccinate one’s child or oneself: a discrete choice experiment rejecting free-riding motives. Soc Sci Med. 2018;207:106–116. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.038.

- Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. COVID-19 vaccine tracker. Baltimore (MD); 2021. [ accessed 2022 Feb 24]. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/covid-vaccine-tracker-global-distribution/.

- Ministry of health and family welfare, government of India. CoWIN dashboard. [ accessed 2021 Feb 24]. https://dashboard.cowin.gov.in/.

- Larson HJ, Clarke RM, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Levine Z, Schulz WS, Paterson P. Measuring trust in vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14(7):1599–1609. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1459252.

- Baker DW. Trust in health care in the time of COVID-19. Jama. 2020;324(23):2373–2375. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.23343.

- Cristea D, Ilie DG, Constantinescu C, Fîrțală V. Vaccinating against COVID-19: the correlation between pro-vaccination attitudes and the belief that our peers want to get vaccinated. Vaccines. 2021;9(11):1366. doi:10.3390/vaccines9111366.

- Sasaki S, Saito T, Ohtake F. Nudges for COVID-19 voluntary vaccination: how to explain peer information? Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114561. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114561.

- Afolabi AA, Ilesanmi OS. Dealing with vaccine hesitancy in Africa: the prospective COVID-19 vaccine context. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38. doi:10.11604/pamj.2021.38.3.27401.

- Kanabar K, Bhatt N. Communication interventions to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in India. Media Asia. 2021;48(4):330–337. doi:10.1080/01296612.2021.1965304.

- Reñosa MDC, Landicho J, Wachinger J, Dalglish SL, Bärnighausen K, Bärnighausen T, McMahon SA. Nudging toward vaccination: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(9):e006237. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006237.

- O’-Leary ST, Riley LE, Lindley MC, Allison MA, Albert AP, Fisher A, Jiles AJ, Crane LA, Hurley LP, Beaty B, et al. Obstetrician–gynecologists’ strategies to address vaccine refusal among pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(1):40–47. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

- Rimal RN, Storey JD. Construction of meaning during a pandemic: the forgotten role of social norms. Health Commun. 2020;35(14):1732–1734. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1838091.

- Jaffe AE, Graupensperger S, Blayney JA, Duckworth JC, Stappenbeck CA. The role of perceived social norms in college student vaccine hesitancy: implications for COVID-19 prevention strategies [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jan 26]. Vaccine. 2022;40(12). SS0264–1. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.01.038.

- Sinclair S, Agerström J. Do social norms influence young people’s willingness to take the COVID-19 vaccine? [published online ahead of print, 2021 Jun 11]. Health Commun. 2021:1–8. doi:10.1080/10410236.2021.1937832.

- Cookson D, Jolley D, Dempsey RC, Povey R, Gesser-Edelsburg A. A social norms approach intervention to address misperceptions of anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs amongst UK parents. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0258985. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258985.

- Ryan M, Marlow LAV, Forster A. Countering vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women in England: the case of Boostrix-IPV. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):4984. doi:10.3390/ijerph17144984.

- Klüver H, Hartmann F, Humphreys M, Geissler F, Giesecke J. Incentives can spur COVID-19 vaccination uptake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(36):e2109543118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2109543118.

- Böhm R, Betsch C, Korn L. Selfish-Rational non-vaccination: experimental evidence from an interactive vaccination game. J Econ Behav Organ. 2016;131:183–195. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2015.11.008.

- Veinot TC. We have a lot of information to share with each other”: understanding the value of peer-based health information exchange. Inf Res. 2010;15(4):15–4. http://InformationR.net/ir/15-4/paper452.html

- The World Bank. Data: individuals using the internet – India. 2020. [ accessed 2022 May 9]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=IN.

- Boas TC, Christenson DP, Glick DM. Recruiting large online samples in the United States and India: Facebook, mechanical turk, and qualtrics. Political Sci Res Methods. 2020;8(2):232–250. doi:10.1017/psrm.2018.28.

Appendix A

Survey Questions

Please indicate your age in years

Please indicate your gender

Please indicate your highest level of education completed.

What country do you live in?

Are you currently pregnant?

What country’s flag is pictured? (India)

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine for my child under 18 years of age.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was relevant to me.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was designed for people like me.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad would prompt me to tell someone about the COVID-19 vaccine.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: I agree with the message provided in this ad.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: I agree with the message provided in this ad.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad would prompt me to tell someone about the COVID-19 vaccine.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was designed for people like me.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was relevant to me.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine for my child under 18 years of age.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: I agree with the message provided in this ad.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad would prompt me to tell someone about the COVID-19 vaccine.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was designed for people like me.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was relevant to me.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine for my child under 18 years of age.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: I agree with the message provided in this ad.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad would prompt me to tell someone about the COVID-19 vaccine.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was designed for people like me.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was relevant to me.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine for my child under 18 years of age.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: I agree with the message provided in this ad.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad would prompt me to tell someone about the COVID-19 vaccine.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was designed for people like me.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was relevant to me.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine for my child under 18 years of age.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

Please indicate your age in years

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: I agree with the message provided in this ad.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad would prompt me to tell someone about the COVID-19 vaccine.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was designed for people like me.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad was relevant to me.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine for my child under 18 years of age.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: this ad motivates me to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

Which ad motivates you most to get the COVID-19 Vaccine

There are multiple reasons why someone may not want to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Please rank these reasons in order, with 1 being the most concerning, to 6 being the least concerning. - I do not feel the vaccine is safe

There are multiple reasons why someone may not want to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Please rank these reasons in order, with 1 being the most concerning, to 6 being the least concerning. - I do not feel the vaccine is effective

There are multiple reasons why someone may not want to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Please rank these reasons in order, with 1 being the most concerning, to 6 being the least concerning. - I do not trust the government

There are multiple reasons why someone may not want to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Please rank these reasons in order, with 1 being the most concerning, to 6 being the least concerning. - People I know have not had a good experience getting the vaccine

There are multiple reasons why someone may not want to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Please rank these reasons in order, with 1 being the most concerning, to 6 being the least concerning. - It is cost prohibitive for me to get the vaccine

There are multiple reasons why someone may not want to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Please rank these reasons in order, with 1 being the most concerning, to 6 being the least concerning. - I believe COVID-19 is not real.

Think of the political parties in your country. Which one is most representative of your views?

Enter the following code as a completion code

Enter the following code as a completion code

Please copy and paste your mTurk Worker ID here

Appendix B

Messaging appeal images