ABSTRACT

In Quebec, during the summer of 2021, different strategies to enhance COVID-19 vaccine uptake were implemented (e.g. mobile vaccination clinics, mass communication campaigns, home vaccination). The aim was that at least 75% of 12 years and older individuals receive two doses of COVID-19 vaccines before the fall. This article explores the impact of incentives and disincentive strategies on Quebecers’ intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19. A series of cross-sectional surveys have been ongoing in Quebec since March 2020 to measure Quebecers’ attitudes and behaviors during the pandemic. In July and August 2021, in addition to sociodemographic information, the survey assessed COVID-19 risks perceptions, adherence to and perception of recommended measures (e.g. masks, physical distancing, vaccine lottery, vaccine passport) as attitudes and intention toward COVID-19 vaccines. Descriptive statistics were generated. Between July 9 to September 1, the vaccine uptake (two doses) rose from 62% to 88%. Among respondents who were unvaccinated during the period, 32% reported a positive influence of the lottery on their intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19 and 39% for the vaccine passport. Approximately half (51%) of unvaccinated respondents reported no influence from the two measures, and both positively influenced 20%. The vaccine lottery had a limited impact on willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccines among unvaccinated adults in Quebec, but the implementation of the vaccine passport appears more influential based on survey respondents’ responses.

Introduction

Vaccination against COVID-19 is a crucial strategy to prevent deaths and complications from COVID-19.Citation1 As of 1 July 2021, 83% of Quebecers aged 12 years and older had received the first dose of COVID-19 vaccines and 69%, two doses – with discrepancies in uptake across age groups, areas of residence, and other sociodemographic factors.Citation2 In anticipation of a potential wave of contamination in the fall of 2021, different strategies to maximize COVID-19 vaccine uptake rates were implemented in Quebec over the summer.

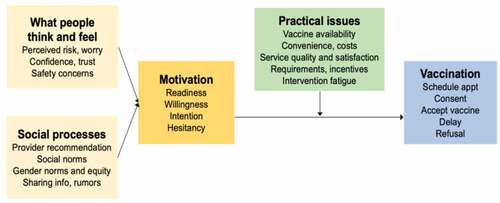

The Increasing Vaccination Model developed by the World Health Organization Behavioral and Social determinants of vaccination (BeSD) working group shows that vaccination behaviors are complex. Effective interventions to increase vaccine acceptance and uptake need to be tailored to local barriers to vaccination that can exist across the four domains (thinking and feeling, social processes, motivation, and practical factors) ()Citation3,Citation4

Many countries have implemented incentives and disincentive strategies to increase intention to be vaccinated (to impact “motivation” in the BeSD model which includes the intention, willingness, and hesitancy of people to get vaccinated). For example, three Canadian provinces have launched lotteries offering prize draws to those vaccinated against COVID-19, and 12 provinces and territories have used a form of mandatory vaccination (i.e., proofs of vaccination or vaccine passports to access to certain locations such as bars and restaurants or social activities such sport events).

Quebec’s incentives-based strategy: “Being vaccinated: It’s a win” lottery

Quebec’s vaccine lottery was announced on July 16, with draws every Friday from August 6 to September 3 for youths (12–17 years) and adults who received a dose of the vaccine in Quebec or had received a vaccine recognized by Health Canada outside of Quebec. Adults who received at least one dose of the vaccine could win weekly prizes of $150,000, and those who received two doses before August 31 could win the big prize ($1 million) or additional prizes (e.g., travel vouchers, cell phones). Adolescents could win weekly scholarships ($10,000) for the first dose and final prizes of $20,000 (for two doses).

Disincentives-based strategies: Quebec’s vaccine passport

In Quebec, the implementation of a vaccine passport to attend some “non-essential” businesses and activities was announced on 5 August 2021. Since its implementation on 1 September 2021, all Quebecers aged 13 and older without medical contraindications to vaccination are required to show proof of adequate protection against COVID-19 (i.e., two doses of vaccines or one dose and a PCR-confirmed infection) to attend outdoor events and festivals, bars and restaurants, gyms and recreation centers.Citation4 Since 14 March 2022, this measure is no longer used in Quebec.

Objective

While incentives and disincentives have been shown effective in increasing vaccine uptake rates for other routine vaccinations, their effectiveness for COVID-19 vaccine uptake rates remains unclear.Citation5 The objective of this study was to explore the perceptions of the vaccine lottery “Being vaccinated, it’s a win Contest’’ and the implementation of vaccine passports among unvaccinated respondents from a series of web panel surveys conducted weekly during the summer of 2021.

Methods

Setting, design, and recruitment

Quebec is one of the 13 jurisdictions of Canada (North America) where approximately 8 millions people lives, of which 85% are French-speaking. The first case of SARS-CoV-2 infection was identified in Quebec in February 2022 and, after the first and second waves, Quebec was the Canadian province with the highest number of cases and deaths due to COVID-19.Citation6

A series of cross-sectional surveys have been ongoing in Quebec since March 2020 to assess Quebecers’ attitudes and behaviors during the pandemic.Citation7 We report this study following the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES).Citation8

A representative sample of Quebec adults of 3,300 respondents was recruited each week using a web panelCitation9to fill out an online questionnaire. This web panel is formed by voluntary participants who subscribe to receive an invitation to fill surveys and from households or individuals recruited by an independent research firm called Leger.Citation9 Their members have agreed to participate in telephone, mail or Internet-Survey research from time to time. An invitation to answer a web-based questionnaire is sent by e-mail by the research firm to potential participants in their panel corresponding to our target population (i.e., representative of Quebec’s population in terms of age, gender, location and language). Each week, approximately 34,000 panelists received the e-mail invitation. Around 11% (i.e., app. 3,750 panelists) opened the link to the survey and 88% of them completed the entire questionnaire (i.e., app. 3,300 respondents).

In addition to sociodemographic questions, the questionnaire contains approximately 60 questions to examine Quebecers’ perceived risk to contract COVID-19, attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge about the pandemic and the preventive measures (including questions regarding vaccination and adherence to conspiracy theories inspired by the Generic Conspiracist Beliefs scaleCitation10 as well as behaviors regarding recommended measures). The questionnaire is adjusted twice a month, items are deleted or added to be able to capture attitudes and perceptions regarding recommended measures (e.g., changes in policy such as mask wearing) and epidemiological context (e.g., detection of new variants). Additional information on the methodology and surveys’ findings is available here.Citation7 Details on items used in this analysis are available in the Supplemental Material 1.

Outcomes measured

One item measured whether respondents had been vaccinated against COVID-19 since December 2020 and how many doses they had received. Another item measured intention to be vaccinated among respondents who responded ‘no’ to the vaccination behavior item. Finally, a general question about vaccine hesitancy was also asked in addition to a series of five items informed by the 5Cs model, a validated approach to calculate a vaccination hesitancy score.Citation11 A question regarding the implementation of the COVID-19 passport was added to the questionnaire for respondents who were not adequately vaccinated (i.e., only one dose, no vaccine) from August 13 to September 1st, 2021 (announcement August 5, implementation September 1st). Vaccine lottery question was asked only to non-vaccinated participants from July 30 to September 1st, 2021 (announcement July 16, draws from August 6 to September 3).

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint is vaccination intent, and the main comparison is whether lottery or passport impacted vaccination intent. Data were weighted according to some sociodemographic characteristics to represent Quebec’s population. Descriptive statistics were generated for all items. Respondents’ sociodemographics were compared with their intention to get vaccinated due to the vaccine lottery and vaccine passport. Respondents’ attitudes (e.g., COVID-19 risk perceptions, adherence to conspiracy theories) and impact of dis- and incentives-based strategies on vaccine intention were compared using the chi-square test. Mantel-Haenszel test was used to compare trends over time. Of note, findings of bivariate analysis apply only to the respondents and cannot be inferred to the whole population of Quebec due to the data collection approach (non-probability sample from a web panel).

Ethics approval

The Ethics Review Board of the Center de recherche du CHU de Québec – Université Laval provided a waiver for this study’s requirement for research ethics approval. The research firm is responsible for the informed consent process and data protection of voluntary participants. The research team receives anonymous data for analysis.

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics and general attitudes of vaccinated and unvaccinated respondents (n = 8911) for the period between August 13th and September 1st are presented in . Overall, 87% of respondents had received two doses of the vaccine, 5% had one dose, and 8% had not received the vaccine during the period.

Table 1. The sociodemographic characteristics and attitudes (%) by COVID-19 vaccination status, August 13 to 1 September 2021.

Respondents aged between 18-and 24 years old, those with a lower level of education, those that were not concerned about catching the virus, those who adhered to conspiracy theories, and those who were vaccine-hesitant in general were more likely not to be vaccinated (p < .0001 for all comparisons).

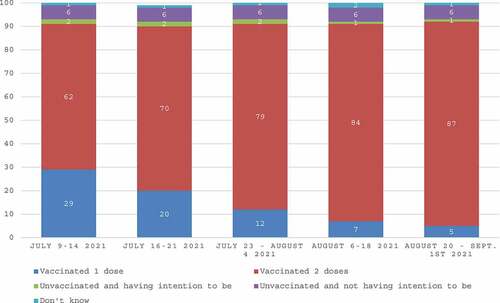

presents the distribution of vaccination status as it evolved between different data collection points from July 9 to 1 September 2021. The vaccine lottery was announced in Quebec on 16 July 2021, and the vaccine passport on 5 August 2021. The first vaccine lottery prize was pulled on 6 August 2021. The proportion of respondents who reported having received a second dose increased, from 70% to 88% (p < .0001) during this period.

Figure 2. Distribution (%) of respondents by vaccination status (number of doses) and vaccine intention (among unvaccinated respondents) across different data collection points, July 9 to 1 September 2021.

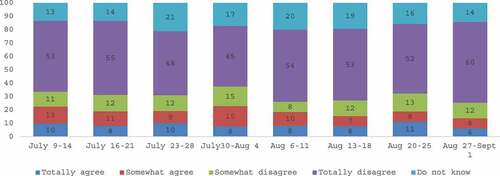

shows detailed responses to the item on intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine among unvaccinated respondents from July 9 to September 1st (n = 2 131). We observed a decrease in intention to be vaccinated (23% to 14%, p = 0.048) during the period. Before the announcement of the vaccine lottery (July 9 to 14), 53% of unvaccinated respondents totally disagreed with the item “I intend to get the vaccine against COVID-19,” while this proportion was 60% for the period from August 27 to September 1st.

Figure 3. Distribution (%) of unvaccinated respondents by intention to receive the covid-19 vaccine, period of July 9 - 1 September 2021.

Respondents who were not vaccinated but expressed positive vaccine intention for the period from July 9 to Sept. 1st were asked whether the announcement of the vaccine lottery contributed to their intention to be vaccinated, and another question about the announcement of the vaccine passport was added in August (Supplemental material 2) shows these results in the context of the aggregate survey questions on vaccination behaviors.

Overall, 32% of unvaccinated respondents reported a positive influence of the lottery on their intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19, 39% for the vaccine passport, and of them, 20% were influenced by both measures. Approximately half (51%) of unvaccinated respondents reported no influence from the two measures.

Discussion

When the vaccine lottery was announced, 91% of our respondents had already received one dose of the vaccine. Among those who were not vaccinated at that time, 32% reported being positively influenced by the lottery. The implementation of vaccine passports seemed to have a slightly higher impact on willingness to be vaccinated, with 39% of unvaccinated respondents reporting being positively influenced by this measure. Of note, 20% of respondents said that they were positively influenced in their decision to vaccinate by both measures. Although the small number of unvaccinated respondents in the surveys limits the strength of the conclusions from this study, our findings indicate that disincentive strategies could be more effective than incentive strategies.

These findings are congruent with other studies that have assessed the impact of lotteries in the context of COVID-19. For example, studies that evaluated the impact of a lottery in Ohio (United States) have shown mixed findings.Citation12,Citation13 One study concluded that the lottery increased the vaccinated share of the state population by 1.5% – about 82,000 people.Citation14 Another study conducted in the United States suggested that incentives to be vaccinated against COVID-19 can be effective, but that the type of incentive matters – smaller cash rewards for all vaccines could be more effective than lotteries.Citation15 A recent overview of the impact of lotteries implemented in Canada also presented the limited impact of this approach.Citation16 In Manitoba, public health representatives reported an increase of “several hundred” vaccination appointments over 5 days after the lottery was announced. In Alberta, people who received the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine increased from 2.6 million to 2.8 million over the summer. Still, it is difficult to attribute this increase only to the lottery as many other initiatives were ongoing at the same time.Citation16

An experimental study showed that vaccine lotteries could positively influence the motivation to be vaccinated among complacent but are likely largely ineffective for vaccine-hesitant individuals (i.e., those who have important doubts and concerns regarding the safety and usefulness of the vaccination).Citation17 Experts recently evaluated the most promising interventions to promote uptake of COVID-19 booster vaccines.Citation18 Their analysis of interventions on several criteria, including expected effectiveness and acceptability, revealed that financial incentives (ex.: vaccine lottery) could promote uptake of COVID-19 booster vaccines. Even if this type of intervention could increase the vaccination rate by a few percentage points, these measures involve high implementation costs. Other approaches to enhancing access to services and using education strategies to communicate that vaccination are safe, necessary, and prosocial could be more cost-effective.Citation19

A study that systematically reviewed the impact on vaccine uptake rates of mandatory and non-mandatory vaccination programs across Europe concluded that their effectiveness was highly dependent on the context.Citation20 Concerning COVID-19, the findings of a recent study revealed that COVID-19 certification led to an increase in vaccine uptake, with a more significant effect in countries with low uptake before implementation.Citation21 This study also showed that the increase in uptake was the highest among people under 30 years of age and was also influenced by the number of settings in which the passport or certification was required.Citation21

Over the summer and fall of 2021, every Canadian jurisdiction has also implemented a COVID-19 vaccination passport, except in Nunavut. Findings of a study using counterfactual simulations with Canadian data indicate a positive impact of these measures on vaccine uptake rates albeit small,Citation22 similar to what we observed in this study. Self-reported COVID-19 vaccination in our survey findings is closely aligned with the official data on vaccine uptake rates in Quebec from the immunization registry during the summer of 2021 (see Figure in Supplementary Material 3).Citation23 COVID-19 vaccine uptake rates for first doses slowly rose over the summer in Quebec. Still, it remains challenging to identify a direct impact of the announcement of the two measures on uptake rates. However, the announcement and implementation of the vaccine passport do coincide with an increase in receipt of first doses.

Finally, despite being a new approach never used before in Quebec, vaccine passports were well accepted by the public. In August 2021, our survey’s findings showed that 76% of Quebecers strongly supported the implementation of the vaccine passport in September in Quebec.Citation24 Similarly, another study conducted across Canada showed that most Canadians (80%) supported the introduction of a vaccination passport in their respective province.Citation25

Limits

Our findings should be interpreted considering some limitations of our approach. In addition to being non-probability samples, they may also be unrepresentative of the population, as those most interested may have responded more quickly. Although the research firm’s web panel is among the largest in Canada, there is also an overall risk of low representativeness for certain population groups. The weighting process can partially correct some representativeness biases but has limitations. Finally, as with any survey, desirability bias should not be overlooked. However, this bias should be minimized since the questionnaire is anonymous and filled out by the respondent himself without the help of an interviewer. The invitation to participate in the survey is the same as for all of the firm’s surveys. It does not mention public health or government, minimizing desirability bias. The proportion of respondents who reported being vaccinated was relatively high, and the small sample of unvaccinated respondents limited the possibility to conduct a multivariate analysis. The vaccine uptake observed is similar to those recorded in Quebec Immunization Registry,Citation23,Citation26 which is also reassuring. We did not have access to data on appointment scheduling. It would have been very interesting to assess whether demand for appointments increases after announcing and implementing those strategies, as the actual vaccination could have occurred weeks later. Finally, although we asked specific questions on the lottery and vaccine passport in our surveys, many other interventions were implemented over the summer 2021 to enhance COVID-19 vaccine uptake rates in Quebec (e.g., mass communication campaigns, opt-in clinics, mobile clinics, etc.). Furthermore, many factors could interfere with a person’s decision to get vaccinated or not at the same time (ex.: the emergence of a new variant). It is therefore impossible to specifically isolate the impact of the vaccine lottery and the announcement of the vaccine passport in Quebec.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results suggested that introducing a vaccine passport may have a slightly higher influence on the intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine than the vaccine lottery. However, during the summer 2021, a proportion of the respondents reported not being influenced by these measures, highlighting that the reasons underlying their vaccine hesitancy might not have been addressed.Citation17 In the context of increased polarization around COVID-19 vaccination decision, understanding the factors leading to vaccine hesitancy and refusal, including system-related barrier issues, remains essential to developing tailored interventions to increase vaccine acceptance and uptake. While incentives and disincentives strategies can immediately impact vaccine uptake rates, maintaining the public’s confi dence in vaccination and building resilience against vaccine disinformation remain crucial for the long-term success of vaccination.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (469 KB)Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux du Québec for funding this study and to the survey participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data are published (https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2100168). Additional information on data can be available upon request to the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2100168.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Canada PHA of. COVID-19 vaccine: Canadian immunization guide [Internet]; 2021 [accessed 2022 Feb 7]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-26-covid-19-vaccine.html

- Canada PHA of. Demographics: COVID-19 vaccination coverage in Canada - Canada.Ca [Internet]. aem2021; [accessed 2022 Jan 27]. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/vaccination-coverage/#a5

- Development of tools to measure behavioural and social drivers (BeSD) of vaccination. Progress report [Internet]; [accessed 2022 Jan 27]. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/immunization/besd_progress_report_june2020.pdf?sfvrsn=10a67e75_3

- COVID-19 vaccination passport [Internet]; [accessed 2021 Dec 21]. https://www.quebec.ca/en/health/health-issues/a-z/2019-coronavirus/progress-of-the-covid-19-vaccination/covid-19-vaccination-passport

- Vaccination programs: requirements for child care, school, and college attendance [Internet]. Guide community prev. serv. community guide2016; [accessed 2022 Feb 11]. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/vaccination-programs-requirements-child-care-school-and-college-attendance

- Institut national de santé publique du Québec. Données COVID-19 au Québec [Internet]; 2022 [accessed 2022 Jun 17]. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees

- COVID-19 - Sondages sur les attitudes et comportements des adultes québécois | INSPQ [Internet]; [accessed 2022 Feb 11]. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/sondages-attitudes-comportements-quebecois

- Improving the quality of web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) | the EQUATOR network [Internet]; [accessed 2022 Mar 18]. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/improving-the-quality-of-web-surveys-the-checklist-for-reporting-results-of-internet-e-surveys-cherries/

- Leger. Panel book [Internet]; [accessed 2021 Feb 26]. https://2g2ckk18vixp3neolz4b6605-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/PANEL-BOOK-LEO-EN.pdf

- Bruder m. Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: conspiracy mentality questionnaire.

- Betsch C, Schmid P, Heinemeier D, Korn L, Holtmann C, Böhm R, Angelillo IF. Beyond confidence: development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PloS One. 2018;13(12):1. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208601.

- Gandhi L, Milkman KL, Ellis S, Graci H, Gromet D, Mobarak R, Buttenheim A, Duckworth A, Pope DG, Stanford A, et al. An experiment evaluating the impact of large-scale, high-payoff vaccine regret lotteries. SSRN Electron J [Internet]; 2021 [accessed 2021 Sep 1]. https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3904365

- Robertson CT, Schaefer KA, Scheitrum D. Are vaccine lotteries worth the money? SSRN Electron J [Internet]; 2021 [accessed 2021 Sep 1]. https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3897933

- Barber A, West J. Conditional cash lotteries increase COVID-19 vaccination rates. SSRN Electron J [Internet]; 2021 [accessed 2021 Sep 1]. https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3894034

- Duch RM, Barnett A, Filipek M, Roope L, Violato M, Clarke P. Cash versus lotteries: COVID-19 vaccine incentives experiment* [Internet]. Health Econ. 2021 Sep 1. doi:10.1101/2021.07.26.21250865

- Duong D. Closing Canada’s COVID-19 vaccination gap. CMAJ. 2021;193(38):E1505–6. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1095963.

- Taber JM, Thompson CA, Sidney PG, O’-Brien A, Updegraff J. Experimental Tests of how hypothetical monetary lottery incentives influence vaccine-hesitant U.S. adults’ intentions to vaccinate [Internet]. PsyArXiv; 2021 [accessed 2021 Sep 1]. https://osf.io/ux73h

- Böhm R, Betsch C, Litovsky Y, Sprengholz P, Brewer N, Chapman G, Leask J, Loewenstein G, Scherzer M, Sunstein CR, et al. Crowdsourcing interventions to promote uptake of COVID-19 booster vaccines [Internet]; 2022 [accessed 2022 Mar 3]. https://psyarxiv.com/n5b6x/

- Sprengholz P, Henkel L, Betsch C. Payments and freedoms: effects of monetary and legal incentives on COVID-19 vaccination intentions in Germany [Internet]; 2021 [accessed 2022 Mar 3]. https://psyarxiv.com/hfm43/

- legislative_approaches_to_immunization_europe_sabin.pdf [Internet]; [accessed 2021 Dec 21]. https://www.sabin.org/sites/sabin.org/files/legislative_approaches_to_immunization_europe_sabin.pdf

- Mills MC, Rüttenauer T. The effect of mandatory COVID-19 certificates on vaccine uptake: synthetic-control modelling of six countries. Lancet Public Health. 2021;S2468-2667:00273–5.

- Karaivanov A, Kim D, Lu SE, Shigeoka H. COVID-19 vaccination mandates and vaccine uptake [Internet]. National bureau of economic research; 2021 [accessed 2021 Dec 21]. https://www.nber.org/papers/w29563

- Registre de vaccination du Québec [Internet]; [accessed 2022 Mar 1]. https://www.quebec.ca/sante/vos-informations-de-sante/registre-de-vaccination-du-quebec

- Faits saillants du 24 août 2021 - Sondages sur les attitudes et comportements des adultes québécois [Internet]. INSPQ; [accessed 2022 Jan 26]. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/sondages-attitudes-comportements-quebecois/24-aout-2021

- Vaccine passports, back-to-school concerns and the delta variant - September 3, 2021 [Internet]. Leger2021; [accessed 21 Dec 2021]. https://leger360.com/surveys/legers-north-american-tracker-september-3-2021/

- Données de vaccination contre la COVID-19 au Québec [Internet]. INSPQ; [accessed 2021 Sep 8]. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees/vaccination