ABSTRACT

Patients with cancer are considered at high risk of COVID-19 related complications with higher mortality rates than healthy individuals. This study investigated the perception, acceptance, and influencing factors of COVID-19 vaccination among cancer patients in Guangzhou, China. A cross-sectional survey was conducted in Guangzhou, China from August to November 2021 in two tertiary medical centers. Outpatients were recruited through hospital posters to complete a questionnaire including demographics, medical history, knowledge, and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccines and COVID-19 vaccination status. Chi-square tests and multivariable logistic regression were used to analyze predictors for acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination. In total, only 75 out of 343 patients (21.87%) had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Twenty-one patients (6.12%) had received a recommendation about COVID-19 vaccination from their physicians. Patients who were recommended by physicians to get vaccinated (aOR = 11.71 95% CI: 2.71–50.66), with a monthly income of more than CNY 5000 (aOR = 3.94, 95% CI: 1.88–8.26) were more likely to have received COVID-19 vaccination. Cancer patients who had been diagnosed for more than one year (aOR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.09–0.51), had received multiple cancer treatment strategies (aOR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.16–0.74), worried about the safety of COVID-19 vaccines (aOR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.11–0.40), were less likely to have received COVID-19 vaccination. COVID-19 vaccination uptake among cancer patients was insufficient. The proportion of cancer patients receiving vaccination recommendations from physicians remains inadequate. Physicians are expected to play an essential role in patients’ knowledge of the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak is a public emergency of international concern on 30 January 2020, which is the highest level of WHO’s alert.Citation1,Citation2 As of 16 June 2022, the cumulative number of confirmed cases and deaths of COVID-19 worldwide has reached 537.22 million and 6.31 million, respectively.Citation3 Older, chronically ill, and immunocompromised patients have been reported to be more susceptible to COVID-19.Citation4–6 Likewise, patients with cancer are particularly more vulnerable to infection than those without cancer and are associated with increased risks of severe complications and death.Citation7,Citation8 The probability of death was 25.6% in this patient population.Citation9

COVID-19 vaccines provide strong protection against serious illness, hospitalization, and death.Citation10 Evidence from prior studies indicated that vaccination would make it less likely to pass the virus on to others.Citation10,Citation11 China has approved six domestic vaccines as of 1 December 2021, including four inactivated vaccines, one adenovirus vector vaccine, and one recombinant protein subunit vaccine.Citation12 As of November 2021, the uptake rate of at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine for the general population in China is about 86.9%, and about 79.5% for people over 60 years old.Citation13,Citation14 However, the available data of COVID-19 vaccination effectiveness in this high-risk population is still limited due to the exclusion and underrepresentation of patients with cancer in most COVID-19 vaccines’ clinical trials – meanwhile, lack of guidelines on whether cancer patients should take the COVID-19 vaccine. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommended that patients with cancer be offered vaccination against COVID-19 as long as components of that vaccine are not contraindicated.Citation15 The European Society for Medical Oncology, the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network COVID-19 Vaccination Advisory Committee supported vaccination in all patients with cancer in their preliminary recommendations.Citation16 The COVID-19 vaccination guidelines issued by the Chinese government recommended that patients with cancer over three years following surgery, together with no longer undergoing radiotherapy and chemotherapy, could take inactivated vaccines or recombinant protein subunit vaccines.Citation17

Several studies suggested that the uptake rate of the COVID-19 vaccination is lower in cancer patients than in the general population due to the limited data on efficacy and safety for cancer patients. A cross-sectional study in eastern China revealed that nearly 36% of cancer patients had been vaccinated against COVID-19.Citation18 In France, 53.7% of cancer patients intend to get vaccinated once the vaccine is available.Citation19 However, multiple studies focused on the early stages of vaccination and emphasized the willingness toward COVID-19 vaccination in cancer patients. A third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine has been applied in several countries worldwide. It has been a seven-month period since the Chinese authorities officially launched a free vaccination program nationwide on 9 January 2021.Citation20 Given the limited data in China, it is imperative to check the COVID-19 vaccination perception and uptake among cancer patients. Consequently, we aimed to investigate the perception and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination among cancer patients in Guangzhou, China.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

The study was performed at the Department of Oncology of the First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University and Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center is the largest integrated center for cancer treatment and care in South China. Outpatients were recruited through hospital posters to complete a questionnaire from August to November 2021. The questionnaires were filled out by the patients themselves unless they had difficulty reading and writing, in which case the trained collectors would conduct face-to-face interviews with patients and record their responses. Eligibility criteria included (1) aged ≥18 years; (2) with any solid or hematologic malignancy and any disease stage; (3) agreeing to participate in this study and providing informed consent. Patients were excluded if they: (1) refused to participate in the survey; (2) received treatment for benign tumors; (3) were unable to communicate due to poor mental status. All participants were asked to report their contact information. The trained interviewers would supplement the missing data by telephone-based interviews. Patients with missing data that cannot be contacted will be excluded from this study. The sample size was calculated using PASS 15 based on the traditional formula for cross-sectional. The uptake of COVID-19 vaccination was estimated to be 30% (according to previously reported studies), a 95% confidence level, and a width of the confidence interval of 5%. The sample size should be 341 patients.

2.2. Questionnaire

The self-reported questionnaire consisted of four sections: (1) demographic data (age, gender, the highest level of education, occupation, income, marital status, residence, smoking, and drinking); (2) medical history (history of chronic diseases, cancer type, cancer diagnosis time, therapy status, therapeutic strategy); (3) knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines (information sources about COVID-19 vaccines, perception of the severity of SARS-CoV-2, frequency of attention to information about the COVID-19 vaccine, recommendation from physicians, and the safety of s COVID-19 vaccine for cancer patients); (4) COVID-19 vaccination (vaccination status, side effects, reasons for vaccination or non-vaccination). A pretest including twenty cancer patients was conducted for modifying questionnaires before the formal survey. All items were closed-ended and treated as categorical variables.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Frequencies and percentages were used to describe the categorical variables. Using the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination as the primary outcome, univariate and multivariable analyses were generated in this study. The Chi-square test was applied to compare the demographic variables, medical history, and knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines between the patients with different COVID-19 vaccination statuses (yes vs. no). Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the predictors for acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination and included variables with P < 0.05 in the univariate analysis. Odds ratios (OR) and their 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were estimated to report the results of the final model. In all analyses, the differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Version 20.0 (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, USA).

2.4. Ethical statement

The Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health (Shenzhen), Sun Yat-sen University, approved the study protocol (SYSU-PHS -2,021,030). Participation was voluntary, and the patient’s informed consent was obtained before completing the questionnaire. Participants were informed about the study’s purposes. All collected information would be anonymized and kept strictly confidential.

3. Results

3.1. Background characteristics

In total, 343 eligible patients completed the questionnaire in this survey (). Amidst these, 152 patients (44.31%) were male, and 191 patients (55.69%) were female. The age of the patients ranged from 20 to 78 years (median: 51 years, interquartile range: 41–59). Seventy-five patients (21.87%) reported that they had already received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Most of the patients were not residents of Guangzhou (68.22%), were married (87.76%), obtained a high school or below education (75.22%), and had a monthly income less than CNY 5000 (USD 785). Overall, the majority of patients had a diagnosis of head and neck cancer (40.23%), followed by breast cancer (14.87%) and gynecologic cancer (12.54%), and most of them were diagnosed within one year. 271 (79.01%) participants were receiving multiple ongoing therapies. The uptake rate of at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine for people over 60 years old was 13.25%, and that of people aged 18–59 was 24.62%.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients surveyed.

3.2. Knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine

As shown in , half of the cancer patients obtained COVID-19-related information by the Internet (50.15%), while merely 4.37% of them preferred to receive information by reading newspapers. Regarding the frequency of following information related to the COVID-19 vaccine, more than half of the patients followed it frequently (58.6%). Concerning the severity of COVID-19, most of the patients acknowledged that the COVID-19 remains a severe infectious disease. However, only 21 (6.12%) patients had received a recommendation about COVID-19 vaccination from their physicians, and 71 (20.70%) patients reported that physicians recommended them not to get vaccinated. Regarding the safety of a COVID-19 vaccine, around half of the patients (50.44%) remain unsure whether the COVID-19 vaccine is safe for cancer patients. In addition, most patients were confused with the national COVID-19 vaccination recommendations (65.31%).

Table 2. Knowledge about and attitude toward the COVID-19 vaccine among cancer patients.

3.3. Predictors for acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination

presents the predictors for acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination among cancer patients. In the multivariate Logistic regression analysis, patients who were recommended by physicians to get vaccinated (aOR = 11.71 95% CI: 2.71–50.66), with a monthly income of more than CNY 5000 (aOR = 3.94, 95% CI: 1.88–8.26) were more likely to have received COVID-19 vaccination. Cancer patients who had been diagnosed for more than one year (aOR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.09–0.51), had received multiple cancer treatment strategies (aOR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.16–0.74), and worried about the safety of COVID-19 vaccines (aOR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.11–0.40) were less likely to have received COVID-19 vaccination.

Table 3. Correlates of COVID-19 vaccination among cancer patients.

3.4. Reasons for vaccination and none-vaccination

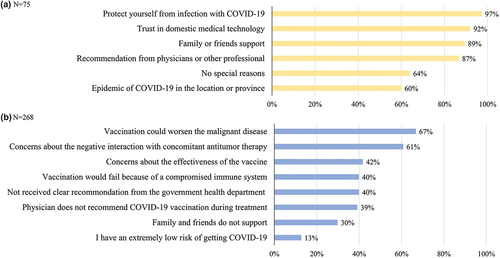

Among 21.87% of participants having at least one dose of any COVID-19 vaccine, the most common reason was to protect themselves from being infected with COVID-19 (97%), followed by the trust in domestic medical technology (92%), supports from family or friends (89%), and recommendations from physicians or other professionals (87%) ().

Figure 1. Reasons to uptake and not to uptake COVID-19 vaccination among cancer patients in China. (a) uptake at least one dose of any COVID-19 vaccine; (b) not uptake any COVID-19 vaccine.

Regarding the reasons for non-vaccination, 67% of participants were concerned that vaccination could worsen the malignant disease. 61% of participants worried about the negative interaction with concomitant antitumor therapy. 42% of participants were concerned about the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine that was developed rapidly. 40% of participants agreed that the vaccine was unlikely to have a protective effect due to the impaired immune system secondary to cancer, and the same proportion of participants demonstrated that they failed to receive a clear recommendation from the local health department for cancer patients. Other reasons were: the physician recommended them not to get COVID-19 vaccination during treatment (39%), family and friends disagreed (30%), and a few patients indicated a low risk of COVID-19 infection (13%).

3.5. Side effects

The most commonly reported side effects are presented in . Swelling and pain at the injection site occurred in 10.61% of the patients following the first dose of the inactivated vaccine, while it reached 12.5% after the second dose. Other general side effects consist of tiredness, myalgia, headache, and runny nose. Notably, two patients demonstrated worsening diabetes ulceration and angina pectoris, respectively, following the first dose of the inactivated vaccine.

Table 4. Commonly reported side effects after COVID-19 vaccination among the 75 participants of the study who received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this investigation represents one of the few studies in China providing insight into COVID-19 vaccination perception and uptake among cancer patients. It was found that the proportion of COVID-19 vaccination was only 21.87% in the current population. Monthly income, time since cancer diagnosis, ongoing treatment, perceptions of the vaccine, and physician’s recommendation were associated with the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination.

Even though most cancer patients indicated willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 in previous studies,Citation21,Citation22 our data showed a low acceptance of the vaccine. This study found that the vaccination rate in the cancer population (21.87%) was much lower than that in the general Chinese population (86.90%). It was only 13.25% among people over 60 years old, which was far lower than the reported vaccine coverage rate (79.50%) for this population during the same period. The uptake rate of the COVID-19 vaccine in this study was also lower than that in prior studies. In Tunisia,Citation23 35.0% of cancer patients have been vaccinated against COVID-19, similar to a cross-sectional survey in Eastern China (35.54%).Citation18 In Serbia, 41% of cancer patients have received a COVID-19 vaccine.Citation24 However, merely 14.5% of cancer patients in Ethiopia have received the first round of the COVID-19 vaccine, and 48.8% refused to get vaccinated.Citation25 Cancer patients seem to be more skeptical of the COVID-19 vaccine than the general population despite the clear recommendations.

Approximately 70% of the patients have not received specific guidance from physicians pertaining to COVID-19 vaccination. Roughly half of the cancer patients remain unsure of the safety of this vaccine. In line with prior studies, our findings showed that the recommendation from physicians is a substantial predictor of COVID-19 vaccination among cancer patients. A nationwide multicenter survey from Korea reported that 91.2% of cancer patients were willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19 under the recommendation of physicians, and nearly 30% can change their decision based on physicians’ recommendations.Citation26 Furthermore, previous studies focused on seasonal influenza vaccination illustrated that the probability of getting vaccinated against influenza was seven times higher when patients were informed about vaccination by physicians.Citation27 Therefore, enhancing physicians’ awareness of this issue and proactively providing education and assistance to patients on COVID-19 vaccination might significantly grow the vaccination coverage.

Our results displayed that patients with higher monthly incomes were more likely to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Previous studies by Jagdish et al.Citation28 and Fisher et al.Citation29 also reported that lower-income individuals were more likely to be hesitant to accept COVID-19 vaccination. This might be attributed to the preexisting vaccine hesitation, lower health literacy and awareness, less communication with physicians, and cost-based concerns in lower-income groups.Citation30–32 This study also showed that patients undergoing multiple treatments and initial cancer diagnosed for over one year have more likelihood of being vaccinated. This finding was consistent with a study from Eastern China indicating that undergoing multiple cancer treatments is a catalyst for patients’ vaccine hesitation.Citation18 Although it has been said that significant two-fold increased risk estimates of death and/or admittance to hospital due to COVID-19 for patients diagnosed with cancer less than one year ago, patients diagnosed with cancers less than a year were more likely to be under active treatment, and therefore, would be considered as the highest risk group of immunosuppression.Citation33 These patients might be more concerned about the negative interaction between vaccines and multiple concomitant antitumor therapies, which is also one of the most common reasons for refusing COVID-19 vaccination in the current study.

In regard to the refusal of vaccination, our findings demonstrated that concerns about the safety and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine among patients with active cancer and insufficient information from the government were considered as other critical wherefores. Similarly, the distrust in the COVID-19 vaccine among cancer patients has also been widely reported. In Tunisia, 74.0% of the patients questioned the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines;Citation23 in Ethiopia, 84.4% were concerned that vaccines would not be effective in cancer patients.Citation25 Currently, there is still controversy as to whether cancer patients can produce antibodies in protective levels subsequently vaccination, even if the growing evidence that COVID-19 vaccines are safe and well-tolerated in these patients.Citation34,Citation35 A cohort study reported that 90% of cancer patients produced adequate antibody response to the mRNA – based vaccine, even though the antibody titers were significantly lower than that produced in healthy controls.Citation36 Moreover, several studies have documented that one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine yields poor efficacy among cancer patients, while a substantial increase in immunogenicity following the second dose despite the antibody titer remaining lower in contrast to healthy controls.Citation35,Citation37,Citation38 Given that cancer patients are at high risk of breakthrough COVID-19, morbidity, and death, the benefits of vaccination outweigh its risks. Patients who have been vaccinated against COVID-19 are supposed to take additional prophylactic measures, such as continuing social distancing, hygiene, and wearing a mask.

Consistent with previous studies,Citation24,Citation34,Citation35 no severe side effects occurred among the study population. The primary side effects were swelling and pain at the injection site, followed by tiredness and myalgia. Side effects afterward the second shot may be harsher than the patients experienced after the first shot. Alfred et al.Citation39 and Waissengrin et al.Citation40 implied no significant difference in side effects between patients undergoing active treatment, including combination with immunotherapy, and patients who did not receive any treatment. Although these data provide adequate evidence for eliminating cancer patients’ concerns about vaccine side effects, continuous safety monitoring for vaccinated patients is acquired to assess the long-term impact on healthfully.

Some limitations should be acknowledged. First, this study was conducted in two tertiary hospitals with limited sample size, generalization should be made cautiously to other geographic locations in China. Second, the questionnaire may not be comprehensive to explain why cancer patients refuse to get vaccinated. Third, the cross-sectional data in this study were prone to potential recall bias and hence failed to establish a causal relationship. Finally, the potential risks of vaccines may be underestimated due to patients who cannot be tracked.

In conclusion, the current findings denoted that the COVID-19 vaccination uptake among cancer patients was insufficient. Income, date of cancer diagnosis, ongoing treatment, perceptions of the vaccine, and physicians’ recommendations were associated with acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination. The proportion of cancer patients receiving vaccination recommendations from physicians remains inadequate. Physicians are expected to play an essential role in patients’ knowledge of the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines.

Author contributions

HZ, ZP conceived the study and designed the protocol with LF and SW. LF, SW, BW, WZ and YS conducted this study. LF and BW contributed to statistical analysis and interpretation of data. LF, SW and HZ drafted the manuscript with all authors critically revising the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, HZ, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations. Emergency committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCov); 2005. https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-2005-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov.

- Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, Zhao J, Liu H, Peng J, Li Q, Jiang C, Zhou Y, Liu S, et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81(2):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021.

- Johns Hopkins University and Medicine. COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- Kim L, Garg S, O’Halloran A, Whitaker M, Pham H, Anderson EJ, Armistead I, Bennett NM, Billing L, Como-Sabetti K, et al. Risk factors for intensive care unit admission and in-hospital mortality among hospitalized adults identified through the US coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET). Clin Infect Dis. 2021 May 4;72(9):e206–e214. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1012.

- Parohan M, Yaghoubi S, Seraji A, Javanbakht MH, Sarraf P, Djalali M. Risk factors for mortality in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Aging Male. 2020;23(5):1416–1424. doi:10.1080/13685538.2020.1774748.

- Fu L, Wang B, Yuan T, Chen X, Ao Y, Fitzpatrick T, Li P, Zhou Y, Lin Y-F, Duan Q, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;80(6):656–665. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.041.

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K, Li C, Ai Q, Lu W, Liang H, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–337. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30096-6.

- Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, Shyr Y, Rubinstein SM, Rivera DR, Shete S, Hsu C-Y, Desai A, de Lima Lopes G, et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. The Lancet. 2020 June 20;395(10241):1907–1918. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31187-9.

- Saini KS, Tagliamento M, Lambertini M, McNally R, Romano M, Leone M, Curigliano G, de Azambuja E. Mortality in patients with cancer and coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and pooled analysis of 52 studies. Eur J Cancer. 2020;139:43–50. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2020.08.011.

- Hodgson SH, Mansatta K, Mallett G, Harris V, Emary KRW, Pollard AJ. What defines an efficacious COVID-19 vaccine? a review of the challenges assessing the clinical efficacy of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(2):e26–e35. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30773-8.

- Chung JY, Thone MN, Kwon YJ. COVID-19 vaccines: the status and perspectives in delivery points of view. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;170:1–25. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2020.12.011.

- COVID19 Vaccine Tracker Team. COVID-19 vaccine development and approvals tracker. [ accessed 2022 Jan 12. https://covid19.trackvaccines.org/country/china/.

- National Health Commission. 2021. https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1716933380465042951&wfr=spider&for=pc.

- National Health Commission. 2021. http://news.china.com.cn/2021-11/30/content_77902447.html.

- Ribas A, Sengupta R, Locke T, Zaidi SK, Campbell KM, Carethers JM, Jaffee EM, Wherry EJ, Soria J-C, D’Souza G, et al. Priority COVID-19 vaccination for patients with cancer while vaccine supply is limited. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(2):233–236. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-20-1817.

- Desai A, Gainor JF, Hegde A, Schram AM, Curigliano G, Pal S, Liu SV, Halmos B, Groisberg R, Grande E, et al. COVID-19 vaccine guidance for patients with cancer participating in oncology clinical trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(5):313–319. doi:10.1038/s41571-021-00487-z.

- National Bureau of Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 vaccination technical guidelines. 1st ed. 2021. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3582/202103/c2febfd04fc5498f916b1be080905771.shtml.

- Hong J, Xu X-W, Yang J, Zheng J, Dai S-M, Zhou J, Zhang Q-M, Ruan Y, Ling C-Q. Knowledge about, attitude and acceptance towards, and predictors of intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine among cancer patients in Eastern China: a cross-sectional survey. J Integr Med. 2022;20(1):34–44. doi:10.1016/j.joim.2021.10.004.

- Barrière J, Gal J, Hoch B, Cassuto O, Leysalle A, Chamorey E, Borchiellini D. Acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among French patients with cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(5):673–674. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.066.

- Zheng W, Sun Y, Li H, Zhao H, Zhan Y, Gao Y, Hu Y, Li P, Lin Y-F, Chen H, et al. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and hesitancy among HIV-infected men who have sex with men in mainland China: a cross-sectional survey. Hum Vaccines Immunotherapeutics. 2021 Dec 2;17(12):4971–4981. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1996152.

- Brodziak A, Sigorski D, Osmola M, Wilk M, Gawlik-Urban A, Kiszka J, Machulska-Ciuraj K, Sobczuk P. Attitudes of patients with cancer towards vaccinations—results of online survey with special focus on the vaccination against COVID-19. Vaccines. 2021 Apr 21;9(5). doi:10.3390/vaccines9050411.

- Kelkar AH, Blake JA, Cherabuddi K, Cornett H, McKee BL, Cogle CR. Vaccine enthusiasm and hesitancy in cancer patients and the impact of a webinar. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 Mar 19;9(3). doi:10.3390/healthcare9030351.

- Khiari H, Cherif I, M’Ghirbi F, Mezlini A, Hsairi M. COVID-19 vaccination Acceptance and its associated factors among cancer patients in Tunisia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2021 Nov 1;22(11):3499–3506. doi:10.31557/apjcp.2021.22.11.3499.

- Matovina Brko G, Popovic M, Jovic M, et al. COVID-19 vaccines and cancer patients: acceptance, attitudes and safety. J Buon. 2021;26(5):2183–2190.

- Tadele Admasu F. Knowledge and proportion of COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors among cancer patients attending public hospitals of addis ababa, Ethiopia, 2021: a multicenter study. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:4865–4876. doi: 10.2147/idr.S340324.

- Chun JY, Kim SI, Park EY, Park S-Y, Koh S-J, Cha Y, Yoo HJ, Joung JY, Yoon HM, Eom BW, et al. Cancer patients’ willingness to take COVID-19 vaccination: a nationwide multicenter survey in Korea. Cancers. 2021 Aug 1;13(15):3883. doi:10.3390/cancers13153883.

- Poeppl W, Lagler H, Raderer M, Sperr WR, Zielinski C, Herkner H, Burgmann H. Influenza vaccination perception and coverage among patients with malignant disease. Vaccine. 2015;33(14):1682–1687. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.02.029.

- Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, Wiblishauser MJ, Sharma M, Webb FJ. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):270–277. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x.

- Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine : a survey of U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Dec 15;173(12):964–973. doi:10.7326/m20-3569.

- Webb FJ, Khubchandani J, Striley CW, Cottler LB. Black-White differences in willingness to participate and perceptions about health research: results from the population-based health street study. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2019 Apr;21(2):299–305. doi:10.1007/s10903-018-0729-2.

- Ferdinand KC, Nedunchezhian S, Reddy TK. The COVID-19 and influenza “twindemic”: barriers to influenza vaccination and potential acceptance of SARS-CoV2 vaccination in African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(6):681–687. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2020.11.001.

- Quinn SC, Jamison AM, Freimuth V. Communicating effectively about emergency use authorization and vaccines in the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(3):355–358. doi:10.2105/ajph.2020.306036.

- Johannesen TB, Smeland S, Aaserud S, Buanes EA, Skog A, Ursin G, Helland Å. COVID-19 in cancer patients, risk factors for disease and adverse outcome, a population-based study from Norway. Front Oncol. 2021;11:652535. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.652535.

- Tran S, Truong TH, Narendran A. Evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine response in patients with cancer: an interim analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2021;159:259–274. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.10.013.

- Monin L, Laing AG, Muñoz-Ruiz M, McKenzie DR, Del Molino Del Barrio I, Alaguthurai T, Domingo-Vila C, Hayday TS, Graham C, Seow J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one versus two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 for patients with cancer: interim analysis of a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(6):765–778. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00213-8.

- Massarweh A, Eliakim-Raz N, Stemmer A, Levy-Barda A, Yust-Katz S, Zer A, Benouaich-Amiel A, Ben-Zvi H, Moskovits N, Brenner B, et al. Evaluation of seropositivity following BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccination for SARS-CoV-2 in patients undergoing treatment for Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021 Aug 1;7(8):1133–1140. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2155.

- Palich R, Veyri M, Marot S, Vozy A, Gligorov J, Maingon P, Marcelin A-G, Spano J-P. Weak immunogenicity after a single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine in treated cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(8):1051–1053. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.04.020.

- Guven DC, Sahin TK, Kilickap S, Uckun FM. Antibody responses to COVID-19 vaccination in Cancer: a systematic review. Front Oncol. 2021;11:759108. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.759108.

- So ACP, McGrath H, Ting J, Srikandarajah K, Germanou S, Moss C, Russell B, Monroy-Iglesias M, Dolly S, Irshad S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine safety in Cancer patients: a single centre experience. Cancers. 2021 July 16;13(14). doi:10.3390/cancers13143573.

- Waissengrin B, Agbarya A, Safadi E, Padova H, Wolf I. Short-Term safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):581–583. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00155-8.