ABSTRACT

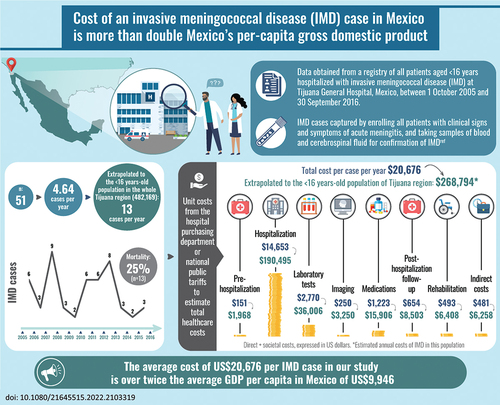

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) is an uncommon but serious and potentially fatal condition mainly affecting children and adolescents. Active surveillance between 2005 and 2016 at Tijuana General Hospital, Mexico, indicated that the incidence of IMD in Tijuana was higher than previously thought, at 2.69 per 100,000 population aged <16 years. The objective of this study was to estimate the economic burden associated with 51 IMD cases in children aged <16 years identified over the 11 years of active surveillance at Tijuana General Hospital, Mexico. Healthcare resource usage for the IMD cases was obtained from the hospital database and combined with unit costs from the hospital purchasing department or national databases to estimate total healthcare costs over a follow-up period of 3 months. Societal costs were represented by the value of lost wages for parents or guardians. All costs were expressed in US$. Over the 11-year study period there were 51 IMD cases, of which 13 (25%) were fatal. The total cost for all 51 cases over the 11-year study period was US$1,054,499 (average per case US$20,676), of which direct healthcare costs comprised US$1,029,948 (average per case US$20,195) and societal costs US$24,551 (average per case US$481). Extrapolated to the population of Tijuana region aged <16 years, the estimated annual economic burden of IMD was US$268,794. The major cost driver was the cost of hospitalization. These data illustrate the significant economic burden associated with IMD in Tijuana, and will be useful in assessing optimal vaccination programs against meningococcal disease in Mexico.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

Introduction

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) is caused by the bacterial pathogen Neisseria meningitidis.Citation1 Most IMD cases are from serogroups A, B, C, W135, X or Y.Citation2 IMD is a serious health problem due to its rapid progression to severe and/or fatal disease.Citation3 Initial symptoms are typically nonspecific in the first few hours, with more specific symptoms such as hemorrhagic rash developing later, and patients may be close to death within 24 hours.Citation4 The most frequent presentations are meningitis and sepsis, with other clinical manifestations such as arthritis and pericarditis also possible.Citation5 The incidence of IMD varies between countries, with estimated annual incidence of < 1 per 100,000 in the United States of America (USA) and EuropeCitation6–8 and 10–100 per 100,000 in the ‘meningitis belt’ of sub-Saharan Africa.Citation9 In Latin America, the incidence of IMD has been reported at 1.9 per 100,000 in Brazil, 1.3 per 100,000 in Uruguay, 0.8 per 100,000 in Chile, and 0.06 per 100,000 in Mexico.Citation10,Citation11 The incidence of IMD varies widely across Latin America, and the very low rates reported in some countries combined with the high proportion of meningitis without identified bacterial etiology probably underestimate the burden of disease in the region.Citation11 IMD incidence is consistently highest in infants aged <1 year in the Latin America region.Citation11 For example, a systematic literature review in Brazil reported incidence rates in infants aged <1 year ranging from 14.7 to 31.3 per 100,000, with the next highest incidence in young children aged 1–4 years, in whom IMD incidence ranged from 7.0 to 11.3 per 100,000.Citation12 In Europe and North America, there is a second IMD peak in adolescents and young adults.Citation13 Data from Chile show no similar second peak in IMD in adolescents in Latin America.Citation14 In the African ‘meningitis belt’ 24 countries have conducted vaccination campaigns against meningitis A and 10 have included the vaccine in routine childhood immunization programs, resulting in a sustained decrease in the incidence of N. meningitidis A in the region. However, the occurrence of large-scale outbreaks remains unpredictable.Citation15 Meningococcal carriage rates peak in late adolescence and young adulthood.Citation9 Studies from Latin America have reported carriage rates of 6.5% in children and adolescents aged 10–19 years in ChileCitation16 and 4% in students aged 18–24 years in Chile.Citation17 In general, throughout the Latin American region, children aged <1 year have a high incidence of IMD while adolescents play an important role in carriage and transmission.Citation18

The mortality rate for meningococcal disease across the world is 5–20%.Citation3,Citation6 In Latin America, IMD case-fatality rates (CFR) are high, reported at 20% in Brazil in 2006, 15% in Uruguay in 2006 and 11% in Chile in 2007.Citation19 In a study of data from Chile over the period 2009–2019, median CFR was reported at 21.6% overall, with a peak of 27.9% in 2015, and CFRs for certain serogroups exceeding 30% in some years.Citation14 Higher rates have been associated with IMD outbreaks.Citation18 Long-term sequelae occur in a substantial proportion of survivors; a systematic literature review of 31 studies reported amputations in up to 8% and skin scars in up to 55% of childhood IMD cases, and hearing loss in up to 19% of infant cases and 13% of childhood cases.Citation20 Even in IMD survivors without sequelae, reduced health-related quality of life persisted for years after infection.Citation20 IMD is also associated with substantial economic burden. Healthcare costs have been estimated at Can$45,768–52,631 per case in Canada,Citation21 US$23,294 per hospitalization in the USA,Citation22 and US$18,920 per case in Denmark.Citation23 IMD is also associated with a substantial economic burden extending beyond healthcare costs. In Germany, the lifetime indirect cost per IMD case resulting from productivity losses of patients or parents was estimated at €2740 using the friction cost approach, and €117,000 using the human capital approach. The indirect cost of IMD could thus be more than twice the total discounted direct costs (estimated at €54,300 per IMD case), depending on the method used.Citation24

In Mexico, the surveillance system Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica (SINAVE) has reported a low estimated national annual incidence of IMD, around 0.056 per 100,000.Citation25 However, cases with symptoms compatible with IMD are not routinely confirmed by culture, which may lead to under-reporting of IMD in Mexico.Citation26 SINAVE is a passive surveillance system, without active case-finding, and such systems are likely to under-report disease incidence.Citation18,Citation27 Active surveillance offers more clinical and epidemiological information, is more robust and more costly, compared with passive surveillance.Citation18 Active surveillance over 11 years (2005 to 2016) conducted at the Tijuana General Hospital in northern Mexico, near the border with the USA, identified 51 cases of IMD, giving an estimated incidence rate of 7.61 per 100,000 in children aged <2 years and 2.69 per 100,000 in children aged <16 years.Citation28 These data indicate that the incidence of IMD in northern Mexico revealed by active surveillance may be considerably higher than suggested by the SINAVE data, comparable with incidence in the USA.Citation26 Information on the impact of IMD on healthcare resource utilization, healthcare cost and societal cost is currently lacking in Mexico. The objective of the present study was to address this by investigating the healthcare and indirect costs associated with the acute phase of IMD and the short-term management of sequelae (up to 3 months after hospital discharge) in children aged <16 years in Tijuana, Mexico. By combining this information with the previously published incidence data from Tijuana,Citation28 we also estimated the economic burden for acute (up to 3 months after hospital discharge) IMD in children and adolescents in this region of Mexico.

Materials and methods

Patient population

Data were obtained from a registry of all patients aged <16 years hospitalized with IMD at Tijuana General Hospital, Mexico, between 1 October 2005 and 30 September 2016. The Mexican national health system is divided into four health insurance systems: ‘IMSS’ (Mexican Insurance for Social Workers); ‘ISSSTE’ (Insurance for Federal Government Workers); ‘ISSSTE per State’ (Insurance for State Government Workers); and ‘Seguro Popular’ (Popular Insurance) which covers the rest of the population not covered by the other insurance systems.Citation28 Tijuana General Hospital belongs to Seguro Popular, and all patients who live in Tijuana and are in Seguro Popular attend only the Tijuana Hospital. Active surveillance captured all IMD cases by enrolling all patients with clinical signs and symptoms of acute meningitis, clinical febrile purpura and/or sepsis, and taking samples of blood and cerebrospinal fluid for confirmation of IMD by conventional isolation from all positive cultures and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).Citation28 The database/registry contained all aggregated anonymized data from each patient during hospitalization and for three months of post-discharge care. Data were formatted in Microsoft Excel.

All patients received the hospital’s standard of care.

Healthcare costs per IMD case

Healthcare resource usage was obtained from the database and included the following information for each IMD case:

Pre-hospitalization: number of ambulatory consultations and emergency room consultations;

Hospitalization: number of days of intensive care unit (ICU) and non-ICU hospital treatment, number of laboratory tests for disease diagnosis and progression, imaging studies, antibiotic treatment and vasopressor treatment;

Post-hospitalization: number of follow-up consultations and rehabilitation therapies for patients with sequelae for up to three months after discharge (estimated at 20 sessions for mild sequelae, 40 sessions for moderate sequelae and 60 sessions for severe sequelae, based on hospital standards and a personal communication from the hospital specialist in Rehabilitation Medicine).

This information on absolute numbers of healthcare resources used for the IMD cases included in the study, recorded in the hospital database, was multiplied by unit costs for each type of resource, obtained from the hospital purchasing department or the national tariff (). All cost estimates collected in Mexican currency were converted to April 2021 US dollars (US$) ($20.00 Mexican pesos = 1.00 US$).

Table 1. Unit costs of healthcare resources.

Societal costs per IMD case

Indirect or societal costs were estimated as lost wages for the patient’s parent or guardian. We assumed that only one of the parents worked full-time, and that working days included weekends. The value of lost wages was based on Mexican national average data of US$16.60 per day (2020 value),Citation29 multiplied by the total number of pre-hospitalization consultations, days in hospital, post-hospitalization consultations and therapy consultations recorded across the 51 cases. We then divided this total by 51 to obtain the average societal cost per case.

Annual IMD cases in Tijuana region

To estimate the total number of IMD cases annually in the whole Tijuana region, we extrapolated the annual IMD incidence rate of 2.69 cases per 100,000 population in children aged <16 years from our previous publicationCitation28 to the population aged <16 years in Tijuana region (482,169).Citation30 As the Tijuana General Hospital belongs to the Seguro Popular health insurance system, and all patients who live in Tijuana and are in Seguro Popular attend only the Tijuana Hospital, the denominator used to calculate the IMD incidence rate was the population who belongs to the Seguro Popular in Tijuana.Citation28

Annual IMD economic burden in Tijuana region

To estimate the annual economic burden of IMD in children aged <16 years in Tijuana region, we multiplied the estimated annual total number of IMD cases in Tijuana region by the average healthcare cost per IMD case and the average societal cost per IMD case. Summing the healthcare cost and societal cost gave the estimated total annual economic burden of IMD in Tijuana region.

Results

Patient characteristics and outcomes

A total of 51 IMD cases were identified in children and adolescents aged <16 years at Tijuana General Hospital over the study period, as previously published.Citation28 summarizes the patients’ demographic characteristics and clinical outcomes. The median age was 36 months (range 3 days to 15 years), and 28 patients (55%) were male. All patients were resident in Tijuana. One patient, who developed a serogroup B related IMD, had received tetravalent (A, C, Y, W) meningococcal conjugate vaccine in California, USA; all other cases had not received meningococcal vaccination. Of the 51 cases, 13 (25%) were fatal, and 12 of the 38 survivors (32%) developed sequelae requiring rehabilitation therapy.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics and outcomes of IMD cases in children aged <16 years at Tijuana General Hospital during the study period.

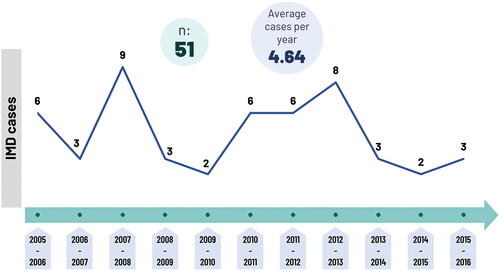

The average number of cases per year over the study period was 4.64 per year, ranging from 2 cases to 9 cases per year ().

Healthcare costs of IMD

summarizes the number of healthcare resource units utilized across all 51 IMD cases and the average number per case, together with the cost across all 51 cases for each type of healthcare resource. All cases were diagnosed with a complete diagnostic kit comprising blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture, PCR for meningococcus, CSF cytochemistry, and Gram stain. In addition, patients required laboratory controls to evaluate their progress and response to treatment, conducted three times per patient per day for patients in ICU and once per patient per day in non-ICU care. A set of imaging studies (chest and abdominal X-ray, brain computed tomography [CT] and echocardiogram) were conducted for each patient on admission. Medication costs included only antibiotics and vasopressor drugs since these were the only available data.

Table 3. Direct healthcare costs associated with IMD cases in children aged <16 years at Tijuana General Hospital during the study period.

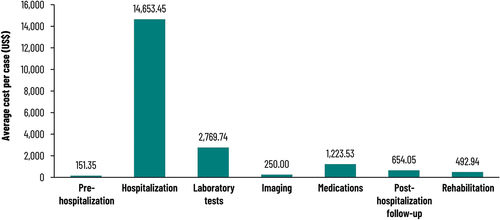

presents the total costs for each component of direct healthcare costs across the 51 IMD patients in the study.

Figure 2. Average direct healthcare costs (US$) per case associated with the 51 IMD cases that occurred in children aged <16 years at Tijuana General Hospital during the study period. Total direct healthcare cost per case = US$20,195.

Societal costs of IMD

The total number of days of lost wages was 1479 across the 51 cases (average 29 days per case), comprising 153 days pre-hospitalization, 570 days of hospital stay, 456 days for post-hospitalization follow-up and 300 days for rehabilitation therapy. Multiplying this by the average daily wage in Mexico gave a total of US$24,551 for societal costs across all the cases during the 11-year study period (average of US$481 per case).

Total economic burden of IMD

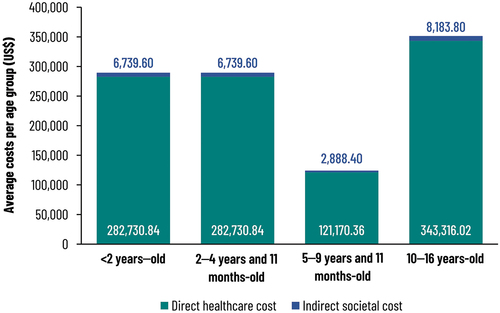

Summing the direct healthcare costs and societal costs gave a total of US$1,054,499 across the 51 cases (average US$20,676 per case). shows the distribution of the overall cost by age group. Costs were highest in adolescents aged 10–16 years ().

Total annual economic burden of IMD in Tijuana region

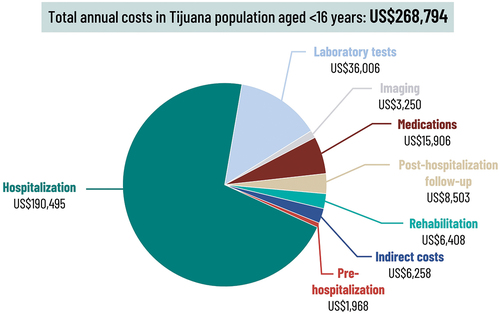

At an annual incidence rate of 2.69 cases per 100,000 population in children aged <16 years, as reported in our previous publication,Citation28 the annual number of IMD cases expected in Tijuana region would be 13. shows the estimated total annual cost of these IMD cases in Tijuana region, including both direct healthcare and societal costs. Direct healthcare costs accounted for most of the economic burden.

Discussion

This study estimated the economic burden associated with cases of acute IMD (follow-up period up to 3 months after hospital discharge) in children and adolescents aged <16 years admitted to the Tijuana General Hospital in Mexico over an 11-year period from 1 October 2005 to 30 September 2016. Our results showed that the direct healthcare costs totaled US$1,029,948 across the 51 IMD cases reported during the 11-year study period, an average of US$20,195 per case. The societal cost of parents’ or guardians’ lost wages totaled US$24,551, an average of US$481 per case, and the total cost was US$1,054,499, an average of US$20,676 per case. Extrapolating these costs to the whole Tijuana region, based on the incidence of IMD in the population aged <16 years from our previous publication,Citation28 and population data, gave an estimate of US$268,794 for the overall annual economic burden of IMD (direct healthcare costs US$262,536 and societal costs US$6,258). To our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of the economic burden of IMD in children and adolescents in Mexico. As such it provides valuable information for healthcare decision-makers on the economic consequences of this uncommon but serious illness.

An earlier study investigated the burden of IMD in Latin America and the Caribbean, coordinated by the Sabin Vaccine Institute in collaboration with the Pan American Health Organization, the International Vaccine Access Center at Johns Hopkins University, and the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention.Citation31,Citation32 This study suggested that the cost per IMD case could be up to US$6,228 per patient, varying in countries across the region,Citation32 which is considerably lower than the cost reported in the present study. A further study of the cost of managing two IMD outbreaks in Brazil and Colombia reported the acute cost during the disease response and disease surveillance phase (up to 1 month) at US$11,475 per IMD outbreak case in Brazil and US$123 per IMD outbreak case in Colombia.Citation33 The estimate in Colombia included only the cost of personnel and chemoprophylaxis, whereas the estimate in Brazil also included the costs of gasoline, office supplies and vaccination.Citation33 The present study provides detailed cost data obtained from real patients treated over 11 years of active surveillance in Mexico, and is a valuable addition to the limited available evidence.

Our study covered only the acute phase of IMD disease, up to three months after hospital discharge. We did not attempt to estimate the long-term costs of sequelae. A modeling study estimating the lifetime costs of IMD in Germany found that sequelae accounted for 81% of the total direct cost.Citation24 Indirect costs associated with sequelae, resulting from productivity losses for patients or parents caring for a child, were estimated at €1210 per survivor using the friction cost approach or €88,200 per survivor using the human capital approach.Citation24 Lost productivity resulting from premature mortality was estimated at €213 per case using the friction cost method (children aged <15 years incur no premature mortality cost using this approach because they are not part of the labor force), or €355,000 per death using the human capital approach.Citation24 These are clearly substantial costs, and as 12 of the 38 survivors (32%) experienced sequelae in our study, not including these long-term costs will result in a significant under-estimate of the overall costs of IMD over a long time horizon.

As is the case for most diseases affecting children, our findings indicate that the majority of the total economic burden comes directly from the use of healthcare resources (direct costs). However, societal costs also should be considered as a significant part of the total economic burden to society. This is particularly true for a severe disease such as IMD which causes long-term sequelae in a substantial proportion of cases, resulting in long-term productivity losses first for parents caring for disabled children and then for the children themselves as they reach working age. In this study, societal costs may likely be underestimated as we only considered the loss of parents’ or guardians’ daily wages as a measure of societal cost, and did not include other costs such as transportation, medications before hospitalization or productivity loss. We also assumed that only one parent lost wages, and that the number of days of lost wages was the same as the number of consultations or days in hospital for the child with IMD. If more than one parent experienced wage loss, or if additional days were lost, this could result in underestimation of the cost of lost wages. Furthermore, we did not attempt to estimate the economic impact of future lost productivity from premature mortality in the 25% of IMD cases who died, or costs associated with long-term disability (which can occur in up to 20% of survivorsCitation32 or costs such as long-term rehabilitation or special nutrition in the 12 (32%) survivors with sequelae. For example, a study in Denmark reported that including the productivity loss from premature death substantially increased the economic burden of IMD.Citation23 An alternative approach to estimating societal costs, the human capital approach, includes the value of an average individual’s future earnings until retirement age and would therefore capture the economic impact of lost productivity due to premature mortality or disability. Using this approach would result in a much larger estimate for societal cost than our estimate. However, it also requires making substantial assumptions leading to uncertainty in the calculations, and therefore we decided not to use the human capital approach in this study, despite the potential for underestimation of societal costs.

Within direct healthcare costs, our results indicated that hospitalization was the major component, accounting for 73% of healthcare costs per case (). This finding is consistent with other studies of the cost of IMD which have shown hospital admission to be a major cost driver in DenmarkCitation23 and Canada.Citation21 However, as our study covered the acute phase of disease only (up to 3 months post-hospitalization), our estimate of direct cost does not include the cost of managing long-term disability due to sequelae. A modeling study from Germany estimated that sequelae accounted for 81% of direct costs over a lifetime horizon,Citation24 and therefore our study will have under-estimated total direct costs over the long term.

Hospitalization costs in our study were US$14,653 per IMD case, which is broadly similar to values reported from high-income countries including Denmark (US$12,370),Citation23 Canada (Can$40,075),Citation21 Australia (Aus$12,312)Citation34 and the USA (US$23,294).Citation22 This is potentially of concern since the economy of Mexico is not comparable to these high-income countries. For example, the average gross domestic product (GDP) per capita for Mexico was US$8,329 in 2020, compared with US$63,593 for the USA in the same year.Citation35 This illustrates the high economic burden of IMD to the Mexican healthcare system in relation to the country’s income. Indeed, the average cost of US$20,676 per IMD case in our study is over twice the average GDP per capita in Mexico of US$8,329.35 Furthermore, inequalities in health and healthcare remain a challenge to the health system in Mexico, despite recent improvements in health insurance coverage.Citation36,Citation37

Although IMD is a reportable condition in Mexico, few cases are reported to the national surveillance system, leading to an assumption of negligible incidence in Mexico.Citation38,Citation39 However, incidence of IMD in the neighboring USA varies between 0.5 and 1.5 cases per 100,000 population,Citation40 and studies using active surveillance have reported similar or higher incidence rates in the Tijuana region of Mexico.Citation26,Citation28 Furthermore, a well-documented outbreak of IMD with high fatality occurred in Tijuana in 2013,Citation41 indicating that IMD is associated with a considerable disease burden in Mexico. A quadrivalent vaccine is available (although not widely used) against serogroups A, C, W and Y and further vaccines against serogroup B. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends large-scale meningococcal vaccination programs in countries with annual IMD incidence of 2–10 cases per 100,000 population and vaccination of risk groups (such as children and young adults in closed communities) where annual IMD incidence is <2 cases per 100,000.Citation2 The incidence rates reported for IMD of 3.08 per 100,000Citation26 and 2.69 per 100,000Citation28 would make the Tijuana region of north-western Mexico a candidate for large-scale meningococcal vaccination under these criteria. The results presented here build on this evidence of substantial IMD disease burden by indicating that IMD is also associated with significant economic burden in the Tijuana region. The average cost of an IMD case was higher than costs reported in Mexico for chronic kidney disease (US$9,091 per case per year),Citation42 or children hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus infection (US$8,313 per case).Citation43 Cost-effectiveness evaluation of meningococcal vaccination in north-western Mexico, using the cost data from the present study, would be a potentially valuable area for future research.

The main strengths of our study are that it estimated costs using real data on healthcare resource usage associated with treating real IMD cases over 11 years of active surveillance. This surveillance started in the emergency room with immediate cultures and samples for PCR taken prior to the start of antibiotics and immediately sent to the microbiology laboratory for rapid processing. In addition, this surveillance methodology was strengthened by a close communication between clinicians and laboratory personnel.

Nevertheless, the study also had some limitations. First, data were obtained from a single hospital, Tijuana General Hospital, which may not be representative of the whole country. Tijuana General Hospital belongs to the Seguro Popular health insurance system, and it is possible that cases in patients who attended private hospitals would not be captured in our study, potentially leading to under-reporting. The results may not be generalizable to other regions of Mexico, as the incidence of IMD elsewhere in the country is unknown. However, the unit costs and healthcare resource usage data obtained in this study may be applicable to future research estimating the economic impact of IMD in other regions if further active surveillance programs are established to provide robust incidence data elsewhere in Mexico. Second, we did not include the costs generated during the 2013 outbreak, in which costly public health measures including antibiotic treatment and questionnaires were implemented. Third, costs of prophylaxis to close contacts were not included. Fourth, societal costs included only lost daily wages for one parent and therefore did not include work undertaken by the other parent, although at least 20 of the 51 mothers contributed to the family economy by informal work. Furthermore, other societal costs such as productivity losses due to long-term disability resulting from sequalae were not included. Fifth, we only included short-term rehabilitation costs up to three months after hospital discharge; as discussed above, this could result in a substantial underestimate of long-term direct costs as sequelae have been estimated to account for 81% of direct costs over a lifetime horizon.Citation24 Sixth, pre-hospital medication costs, and medication costs other than antibiotics and vasopressors, were not included due to an absence of data. These limitations would tend to underestimate the cost of IMD, and therefore the overall economic impact of IMD in Mexico may be higher than reported here.

In conclusion, this study provides the first estimate of the economic burden of IMD in children and adolescents in Mexico. Our findings indicate that IMD was associated with significant economic burden, averaging US$20,676 per case for acute treatment (up to 3 months after hospital discharge). Results of this study may be useful in assessing optimal vaccination programs against meningococcal disease in Mexico.

Supplemental Online Appendix

Download MS Word (14.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Business & Decision Life Sciences platform for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination, on behalf of GSK. Pierre-Paul Prevot coordinated manuscript development and editorial support. Carole Nadin (Fleetwith Ltd, on behalf of GSK) provided writing support, Janne Tys provided design support.

Disclosure statement

DVO, AGH, MYCA, GHG are employees in the GSK group of companies and hold shares in the GSK group of companies. ECC and EZLR declares fees from GSK during the conduct of this study. Authors declare no other financial and non-financial relationships and activities.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2103319

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chang Q, Tzeng YL, Stephens DS. Meningococcal disease: changes in epidemiology and prevention. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:1–10. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S28410.

- World Health Organization. Meningococcal vaccines: WHO position paper. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2011;86. p. 521–540.

- Pace D, Pollard AJ. Meningococcal disease: clinical presentation and sequelae. Vaccine. 2012;30(Suppl 2):B3–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.062.

- Thompson MJ, Ninis N, Perera R, Mayon-White R, Phillips C, Bailey L, Harnden A, Mant D, Levin M. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet. 2006;367(9508):397–403. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67932-4.

- Vazquez JA, Taha MK, Findlow J, Gupta S, Borrow R. Global meningococcal initiative: guidelines for diagnosis and confirmation of invasive meningococcal disease. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(14):3052–3057. doi:10.1017/S0950268816001308.

- Cohn AC, MacNeil JR, Harrison LH, Hatcher C, Theodore J, Schmidt M, Pondo T, Arnold KE, Baumbach J, Bennett N, et al. Changes in Neisseria meningitidis disease epidemiology in the United States, 1998-2007: implications for prevention of meningococcal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(2):184–191. doi:10.1086/649209.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meningococcal disease; 2020 [accessed 2021 Sep 10]. https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/surveillance/index.html.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance atlas of infectious diseases; 2021 [accessed 2021 Sep 10]. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/surveillance-atlas-infectious-diseases.

- Pelton SI. The global evolution of meningococcal epidemiology following the introduction of meningococcal vaccines. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(2 Suppl):S3–S11. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.012.

- Vespa Presa J, Abalos MG, Sini de Almeida R, Cane A. Epidemiological burden of meningococcal disease in Latin America: a systematic literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;85:37–48. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2019.05.006.

- Safadi MA, Cintra OA. Epidemiology of meningococcal disease in Latin America: current situation and opportunities for prevention. Neurol Res. 2010;32(3):263–271. doi:10.1179/016164110X12644252260754.

- Vespa Presa J, de Almeida RS, Spinardi JR, Cane A. Epidemiological burden of meningococcal disease in Brazil: a systematic literature review and database analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;80:137–146. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2019.01.009.

- Jafri RZ, Ali A, Messonnier NE, Tevi-Benissan C, Durrheim D, Eskola J, Fermon F, Klugman KP, Ramsay M, Sow S, et al. Global epidemiology of invasive meningococcal disease. Popul Health Metr. 2013;11(1):17. doi:10.1186/1478-7954-11-17.

- Villena R, Valenzuela MT, Bastias M, Santolaya ME. Invasive meningococcal disease in Chile seven years after ACWY conjugate vaccine introduction. Vaccine. 2022;40(4):666–672. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.075.

- World Health Organization. Control of epidemic meningitis in countries in the African meningitis belt, 2019. Weekly Epidemiological Rec 2020;95:133–144.

- Diaz J, Carcamo M, Seoane M, Pidal P, Cavada G, Puentes R, Terrazas S, Araya P, Ibarz-Pavon AB, Manriquez M et al. Prevalence of meningococcal carriage in children and adolescents aged 10-19 years in Chile in 2013. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9(4):506–515. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2015.12.011.

- Rodriguez P, Alvarez I, Torres MT, Diaz J, Bertoglia MP, Carcamo M, Seoane M, Araya P, Russo M, Santolaya ME. Meningococcal carriage prevalence in university students, 1824 years of age in Santiago, Chile. Vaccine. 2014;32(43):5677–5680. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.015.

- López P, Gentile A, Ávila-Agüero ML, Efron A, Torres CN, Chacón E, Gabastou J-M, Brea J, Torres JP, Falleiros-Arlant LH, et al. Latin American forum on meningococcal disease, Latin American update: its prevention. Arch Pediatr. 2022;7:200.

- Pan American Health Organization. Frequently asked questions on meningococcal disease; 2021 [accessed 2022 Mar 1]. https://www.paho.org/en/documents/frequently-asked-questions-meningococcal-disease.

- Olbrich KJ, Muller D, Schumacher S, Beck E, Meszaros K, Koerber F. Systematic review of invasive meningococcal disease: sequelae and quality of life impact on patients and their caregivers. Infect Dis Ther. 2018;7(4):421–438. doi:10.1007/s40121-018-0213-2.

- Rampakakis E, Vaillancourt J, Mursleen S, Sampalis JS. Healthcare resource utilization and cost of invasive meningococcal disease in Ontario, Canada. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38(3):253–257. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002251.

- O’Brien JA, Caro JJ, and Getsios D. Managing meningococcal disease in the United States: hospital case characteristics and costs by age. Value Health. 2006;9(4):236–243. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00113.x.

- Gustafsson N, Stallknecht SE, Skovdal M, Poulsen PB, Ostergaard L. Societal costs due to meningococcal disease: a national registry-based study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:563–572. doi:10.2147/CEOR.S175835.

- Scholz S, Koerber F, Meszaros K, Fassbender RM, Ultsch B, Welte RR, Greiner W. The cost-of-illness for invasive meningococcal disease caused by serogroup B Neisseria meningitidis (MenB) in Germany. Vaccine. 2019;37(12):1692–1701. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.013.

- Safadi MA, Gonzalez-Ayala S, Jakel A, Wieffer H, Moreno C, Vyse A. The epidemiology of meningococcal disease in Latin America 1945-2010: an unpredictable and changing landscape. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141(3):447–458. doi:10.1017/S0950268812001689.

- Chacon-Cruz E, Sugerman DE, Ginsberg MM, Hopkins J, Hurtado-Montalvo JA, Lopez-Viera JL, Lara-Munoz CA, Rivas-Landeros RM, Volker ML, Leake JA. Surveillance for invasive meningococcal disease in children, US-Mexico border, 2005-2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(3):543–546. doi:10.3201/eid1703.101254.

- Thacker SB, Choi K, Brachman PS. The surveillance of infectious diseases. JAMA. 1983;249(9):1181–1185. doi:10.1001/jama.1983.03330330059036.

- Chacon Cruz E, Alvelais Palacios JA, Lopatynsky Reyes EZ, Rodriguez Valencia JA, Volker Soberanes ML. Meningococcal disease in children: eleven years of active surveillance in a Mexican hospital and the need for vaccination in the Tijuana region. J Infec Dis Treat. 2017;3(01):1–4. doi:10.21767/2472-1093.100031.

- Datosmacro C Expansión - México Salario minimo; 2020 [accessed 2021 Sep 10]. https://datosmacro.expansion.com/mercado-laboral/salario-medio/mexico.

- INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda; 2020 [accessed 2021 Sep 10]. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/boletines/2021/EstSociodemo/ResultCenso2020_BC.pdf.

- Sabin Vaccine Institute. Sizing up a killer: understanding meningococcal disease in Latin America 2021 [accessed 2021 Oct 2]. https://www.sabin.org/updates/blog/sizing-killer-understanding-meningococcal-disease-latin-america.

- Pan-American Health Organization. New study reveals significant healthcare system costs associated with meningococcal disease; 2012 [accessed 2021 Oct 2]. https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=6542:2012-importantes-costos-salud-asociados-meningococica&Itemid=135&lang=en.

- Constenla D, Carvalho A, Alvis Guzman N. Economic impact of meningococcal outbreaks in Brazil and Colombia. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2(4):ofv167. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofv167.

- Wang B, Haji Ali Afzali H, Marshall H. The inpatient costs and hospital service use associated with invasive meningococcal disease in South Australian children. Vaccine. 2014;32(37):4791–4798. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.05.069.

- World Bank. GDP per capita (current US$); 2020 [accessed 2022 Mar 1]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD.

- Barraza-Llorens M, Panopoulou G, Diaz BY. Income-Related inequalities and inequities in health and health care utilization in Mexico, 2000-2006. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013;33(2):122–130, 129 ppreceding 122. doi:10.1590/s1020-49892013000200007.

- Urquieta-Salomon JE, Villarreal HJ. Evolution of health coverage in Mexico: evidence of progress and challenges in the Mexican health system. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(1):28–36. doi:10.1093/heapol/czv015.

- Padron F. Meningitis meningocóccica en los niños. Rev Med Hosp Central San Luis Potosi. 1949;1:193–218.

- Almeida-Gonzalez L, Franco-Paredes C, Perez LF, Santos-Preciado JI. Meningococcal disease caused by Neisseria meningitidis: epidemiological, clinical, and preventive perspectives. Salud Publica Mex. 2004;46(5):438–450. doi:10.1590/s0036-36342004000500010.

- Harrison LH. Epidemiological profile of meningococcal disease in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(Suppl 2):S37–44. doi:10.1086/648963.

- Chacon-Cruz E, Espinosa-De Los Monteros LE, Navarro-Alvarez S, Aranda-Lozano JL, Volker-Soberanes ML, Rivas-Landeros RM, Alvelais-Arzamendi AA, Vazquez JA. An outbreak of serogroup C (ST-11) meningococcal disease in Tijuana, Mexico. Ther Adv Vaccines. 2014;2(3):71–76. doi:10.1177/2051013614526592.

- Figueroa-Lara A, Gonzalez-Block MA, Alarcon-Irigoyen J. Medical expenditure for chronic diseases in Mexico: the case of selected diagnoses treated by the largest care providers. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0145177. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0145177.

- Mould-Quevedo JF, Contreras-Hernández I, Martínez-Valverde S, Villasis-Keever MA, Granados-García VM, Salinas-Escudero G, Muñoz-Hernández O. Direct medical costs of treating Mexican children under 2 years of age with respiratory syncytial virus. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2012;69:111–115.