ABSTRACT

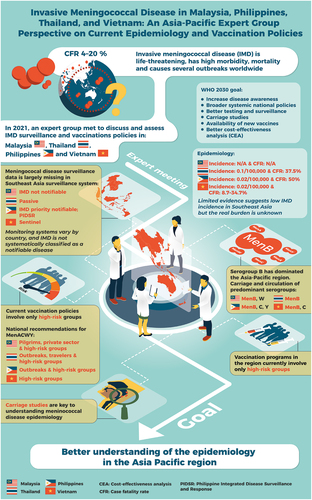

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) imposes a significant burden on the global community due to its high case fatality rate (4-20%) and the risk of long-term sequelae for one in five survivors. An expert group meeting was held to discuss the epidemiology of IMD and immunization policies in Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. Most of these countries do not include meningococcal immunization in their routine vaccination programs, except for high-risk groups such as immunocompromised people and pilgrims. It is difficult to estimate the epidemiology of IMD in the highly diverse Asia-Pacific region, but available evidence indicate serogroup B is increasingly dominant. Disease surveillance systems differ by country. IMD is not a notifiable disease in some of them. Without an adequate surveillance system in the region, the risk and the burden of IMD might well be underestimated. With the availability of new combined meningococcal vaccines and the World Health Organization roadmap to defeat bacterial meningitis by 2030, a better understanding of the epidemiology of IMD in the Asia-Pacific region is needed.

Introduction

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) caused by Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus) imposes a considerable burden worldwide.Citation1–3 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 250,000 deaths due to meningitis in 2019, with one in five affected persons left with long-term severe sequelae.Citation4 The six meningococcal serogroups (MenA, MenB, MenC, MenW, MenX, and MenY) are responsible for almost all cases of IMD worldwide.Citation1,Citation5

Estimating the epidemiology and burden of IMD in the Asia-Pacific region can be very challenging. The recommendations and the organization of communicable disease monitoring systems varies by country and IMD is not classified as a notifiable disease in some countries.Citation6

Material and methods

An expert group meeting was convened to discuss the IMD epidemiology and immunization policies in some Asia-Pacific countries. The objective of the meeting was to consolidate existing information and determine knowledge gaps regarding IMD burden and serogroup distribution in Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, and Vietnam. In addition, current meningococcal immunization policies were reviewed to identify challenges and opportunities for improving immunization. The meeting was held online on 3 March 2021, with 23 participants, including 13 epidemiologists and infectious disease experts from these countries, and 10 experts from the GSK team. The proceedings of this meeting are reflected in this paper.

Malaysia

Incidence data

IMD is not a mandatory notifiable disease. Moreover, there is little incidence data availableCitation7–12 from the earliest publication in 1977Citation7 to the most recent review in 2015Citation13 and all are concerned with retrospective hospital patient records. Based on these retrospective studies, Haemophilus influenzae was found to be the most common cause of meningitis in Malaysia until the H. influenzae type b (Hib) conjugate vaccine was included in the National Immunization Program (NIP) in 2002.Citation14 Since 1980, N. meningitidis is responsible for 3.5–13.0% of meningitis cases in Malaysia.Citation13

Carriage and circulating serogroups

Rohani et al. (2007) found a carriage rate of 37.0% among 3195 healthy young army recruits.Citation15 In Al-Azeri et al. (2002), returning pilgrims had a 51.3% (n = 41/76) higher rate of N. meningitidis compared to pre-hajj.Citation16

Among army recruits, the detected serogroups were either MenX, MenZ or MenY (81.0% cumulative for the three), MenW (4.7%) and MenA (3.3%).Citation15 MenW serogroups were detected in the majority of pilgrims returning from Hajj.Citation16 MenB and MenW were the predominant serogroups among 21% of 123 N. meningitidis genotyped isolates (114 carrier and nine clinical strains).Citation17 During 1987–2004, 11 microbiologically confirmed cases were reported in a large university hospital in Kuala Lumpur; mortality rate was 25%. One of the six serogrouped cases was MenB, while the other five were MenW.Citation11

A pattern of increased N. meningitidis resistance to penicillin has been observed.Citation17,Citation18 Among 123 N. meningitidis strains, 64.9% (74/114) of carrier strains and almost all (8/9, 89.0%) of clinical strains were susceptible to penicillin. Thus, 33.3% of all N. meningitidis strains had intermediate resistance to penicillin.Citation17

Meningococcal vaccination

Routine meningococcal vaccination is recommendedCitation6 for at-risk population, travelers to parts of the world with meningitis epidemics, and Hajj.Citation19,Citation20 Only quadrivalent conjugate meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY) vaccines are available and routinely administered in the private sector on a case-by-case basis, in one or two injections. Hajj pilgrims should receive it within a period of five years to 10 days before pilgrimage.Citation19–22

Thailand

Incidence data

Thailand has a well-established passive surveillance system for communicable diseases, under which healthcare professionals (HCPs) are required to report suspected cases within 24 hours.Citation23 However, confounding factors like low disease awareness among HCPs, low number of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, cost of such PCR tests and antibiotic use prior to laboratory confirmation of the disease, appear to contribute to underestimation of the disease burden.

According to official annual surveillance reports, from 2010 to 2019 the IMD incidence was less than 0.10 per 100,000 population overall.Citation23 In 2012, the case fatality rate (CFR) reached 37.5%.Citation23 The incidence was highest in children aged 0–4 years, with only a few cases reported in adolescents and adults.Citation23 The southern and western borders had the highest incidence of IMD (1971–2019).Citation23

Carriage and circulating serogroups

A retrospective analysis of bacterial cultures and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) specimens collected in 13 public hospitals from 1994 to 1999 reported N. meningitidis in 0.002% and 0.02% of those samples, respectively.Citation24 Penicillin-resistant N. meningitidis isolates, with a minimum inhibitory concentration ≥0.125 g/mL, were also reported.Citation24

Another study found an unadjusted incidence of 24.6 suspected meningitis cases of all causes per 100,000 people.Citation25 Hib, Gram positive cocci, Gram negative bacilli, and N. meningitidis caused 39.1, 26.1, 21.7, and 13.0% of confirmed bacterial meningitis, respectively.Citation25

MenB was predominant (50–80%) among cases diagnosed in 1994–1999Citation6,Citation24 and among 11 clinical isolates of N. meningitidis obtained from Shoklo Malaria Research Unit, Mae Sot in 2007; four of these isolates were resistant to chloramphenicol.Citation26

Meningococcal vaccination

Only MenACWY conjugate vaccines are available in Thailand.Citation27 Meningococcal vaccination is recommended (a) in the event of an outbreak from a vaccine-preventable serogroup (serogroups A, C, Y, and W), (b) for people traveling to countries where the disease is endemic, such as Africa or the Middle East, and (c) for individuals routinely operating in laboratories where N. meningitidis may be present in the form of a solution.Citation28

Philippines

Incidence data

Meningococcal disease is endemic to Philippines, with about 100 cases reported yearly and no seasonal variation.Citation29 It is among the priority notifiable diseases under the Philippine Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (PIDSR) protocol.Citation30 The latest available PIDSR reported 130 meningococcal cases of any severity level, from suspected symptomatic to laboratory confirmed, from January 1 to 29 June 2019.Citation31 The highest incidence was among the youngest age groups: 49.2% (64/130) aged <5 years, and 25.4% (33/130) aged <1 year.Citation31 There were 68 deaths accounting for an overall CFR of 50.0%.Citation31 Aye et al. (2020) reported an annual incidence of 0.02 cases per 100,000 population.Citation6

Carriage and circulating serogroups

MenB caused two of the seven epidemics during 1998–2011, while MenA caused the largest epidemic during 2004–2006 with 418 cases.Citation32,Citation33 In a large prospective, cross-sectional study on carriage among school and university students (age 5–24 years), MenB was the predominant serogroup (65.7%, 23/35) isolated across age groups, followed by MenC (8.6%, 3/35), and MenY (5.7%, 2/35).Citation34 Aye et al. (2020), also reported a predominance of MenB serogroup (68.0% of cases) in 2017–2018 PCR surveillance data and the presence of MenW (16.7%) in 2018 PCR surveillance data.Citation6

Meningococcal vaccination

Meningococcal vaccination is not included in the Philippine Expanded Immunization Program.Citation35 However, polysaccharide and conjugate MenACWY are available in Philippines and vaccination is suggested for immunocompromised individuals, patients with retroviral infections, travelers, pilgrims, and residents of hyperendemic or endemic areas, and during outbreaks.Citation29,Citation33,Citation36

Vietnam

Incidence data

First evidence of IMD in Vietnam involved an outbreak with 1015 cases in Ho Chi Minh City in 1977.Citation37–39 Since 2012, an IMD surveillance system has been implemented in the country.Citation37 In 2018, the incidence rate was 0.02 per 100,000 population.Citation40 High incidence rates have been recorded in surveillance studies, ranging from 1.9 per 100,000 among army recruitsCitation41 to 36.2 per 100,000, among newborns aged less than one month in Hanoi.Citation42 In Hanoi, reported incidence rates for children under the age of five years varied from 2.6 to 7.4 per 100,000.Citation42,Citation43 Reported CFRs are also high, ranging from 8.7%Citation41 to 34.7%.Citation39

Carriage and circulating serogroups

Sporadic cases of MenC were reported in southern Vietnam in 2006 and 2012, and MenC caused an outbreak during 1977–1979.Citation6,Citation38 MenC was predominant in CSF samples and MenB in bacterial isolates from the Kim et al. (2012) study, but the number of samples examined was small.Citation42 Hib was detected in 16.6% of the specimens, N. meningitidis in 14.2%, and S. pneumoniae in 4.7%.Citation42 MenB was the predominant serogroup (94%), among 109 isolates from Southern Vietnam collected between the 1980s and 2019. MenC was only found in 6% of isolates.Citation44 Similarly, MenB predominated among the carrier serogroups at 56% (n = 34), followed by MenC at 21% (n = 13), and the remaining isolates were not typeable.Citation44 A prospective, population-based surveillance study conducted in all Vietnamese military hospitals from January 2014 to June 2021 identified 69 IMD cases, of which 91% were MenB.Citation41

Meningococcal vaccination

Meningococcal vaccine is not provided under the NIP and is recommended only for high-risk groups. MenACWY polysaccharide vaccine and a bivalent B Outer Membrane Vesicles and C meningococcal polysaccharide vaccines are the only meningococcal vaccines available in Vietnam.Citation45,Citation46 These are mainly provided through the private health sector.

Experts commentary

The limited data accumulated so far suggest low incidence of IMD in Southeast Asia, but the burden remains unclear.Citation47 Sporadic cases in the region are now more easily identified due to advances in diagnostic tools, genotyping, and disease awareness (e.g. outbreaks increased appreciation of preventive measures). The available data from the Asia-Pacific region in general,Citation6 and from the four countries in this paper, suggest a shifting epidemiology, with MenB serogroup currently predominating. IMD is not considered a notifiable disease in several countries, and reliable epidemiological data is scarce in the region, necessitating surveillance system improvements.Citation6 The limited N. meningitidis carriage data available are inconclusive due to the variability in the populations involved, the study design, the sample handling and the method of analysis.Citation47 Because most of the disease transmission occurs between carriers,Citation29,Citation47,Citation48 inter-epidemic carriage data are vital to determine the most effective local prevention strategies.Citation6,Citation47 Future research should involve collaborative regional multicenter studies applying similar designs.Citation47 Larger representative populations and age groups across countries would fill evidence gaps and allow regional comparisons of carriage and seroprevalence.Citation47 Pilgrims deserve special consideration in study designs evaluating pre- and post-mass gathering carriage, including vaccination status and potential impact on carriage.

Given the high morbidity and mortality rates of IMD, the experts agreed that vaccination is the most effective approach for prevention in the Asia-Pacific countries considered. Current recommendations are geared toward high-risk groups, travelers and outbreak control. Locally generated disease burden data, based on IMD surveillance evidence, are needed to document the potential need to broaden the existing meningococcal vaccine recommendations.Citation49 MenB and MenACWY conjugate vaccines could be considered eventually in NIPs for immunization of the identified high-risk groups. Their administration to non-high risk groups is currently only possible through the private health sector. Simultaneously, vaccination awareness campaigns should be conducted, considering the problems and impediments to a successful immunization plan. HCPs rarely, if ever, contribute to building up knowledge of local meningococcal disease morbidity, mortality, and medical implications.Citation1,Citation50 Even in countries with available laboratory facilities like Thailand, HCPs rarely order PCR tests. As a necessity, HCPs should receive adequate training in the collection, processing, and diagnosis of clinical samples. Moreover, guidelines should be developed and proactively communicated to HCPs to ensure that clinical samples are appropriately sent for laboratory detection. Simultaneously, awareness should be increased among HCPs regarding meningococcal disease burden.

A graphical abstract of the context, novelty, and impact of the expert meeting that can be shared with patients, healthcare professionals, and decision-makers is available in .

Conclusion

The expert group meeting revealed a paucity of credible monitoring data on IMD epidemiology in Southeast Asia and recognized the severity of the disease and the importance of prevention through vaccination. The absence of robust epidemiological data highlights the importance of implementing reliable surveillance systems.

National immunization programs currently only involve at-risk populations, while the general population can access vaccination only through the private sector. With new combined meningococcal conjugate vaccines available and the WHO roadmap to defeat bacterial meningitis by 2030,Citation50 a better understanding of the epidemiology of IMD in the Asia-Pacific region is warranted. Vaccination has proven successful to contain and control other types of bacterial meningitis, such as Hib. Many countries are currently implementing pneumococcal conjugate vaccine programs and IMD appears as one of the next bacterial meningitis challenges to overcome.

Abbreviations

| CFR | = | case fatality rate |

| CI | = | confidence intervals |

| CSF | = | cerebrospinal fluid |

| HCP | = | healthcare professionals |

| Hib | = | H. influenzae type b |

| IMD | = | Invasive meningococcal disease |

| MenACWY | = | quadrivalent meningococcal ACWY |

| MenAC | = | bivalent A and C meningococcal conjugate vaccine |

| MenBC | = | bivalent B and C meningococcal conjugate vaccine |

| MIC | = | minimum inhibitory concentration |

| NIP | = | national immunization program(s) |

| PCR | = | polymerase chain reaction |

| PIDSR | = | Philippine Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response |

| WHO | = | World Health Organization |

Author contributions

OC and OO were in charge of supervision and project administration and performed data curation and investigation. All authors participated in the discussion and the development of this manuscript and gave final approval before submission.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current work.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the global and regional teams of GSK, in particular, Thanabalan Fonseka; Saravanan Periempam; Kris Lodrono; Minh Nguyen; Jittakarn Mitisubin; Phatu Boonmahittisut; Deliana Permatasari, Huu Khanh Truong, Gaurav Mathur, and Jennifer Belen for their participation in the Expert Group meeting. The authors thank the Business & Decision Life Sciences platform for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination, on behalf of GSK. Athanasia Benekou, on behalf of GSK, provided medical writing support.

Disclosure statement

OC and OO are employed by and hold shares in GSK. JC reports involvement as a member of the board of the Philippine Foundation for Vaccination Inc., and received educational grants from Sanofi Pasteur for participation in meetings as a speaker. MLAMG and TDV received honoraria for the advisory board from GSK for attending the IMD SEA Expert Group meeting. MLAMG is President of the Philippine Foundation for Vaccination. OC, OO, JC, MLAMG and TDV declare no other financial and non-financial relationships and activities. UT, TC, TMD, NTLH, ZI, MMN, ALTOL, TT, and SDT declare no financial and non-financial relationships and activities and no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acevedo R, Bai X, Borrow R, Caugant DA, Carlos J, Ceyhan M, Christensen H, Climent Y, De Wals P, Dinleyici EC. The Global Meningococcal Initiative meeting on prevention of meningococcal disease worldwide: epidemiology, surveillance, hypervirulent strains, antibiotic resistance and high-risk populations. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18(1):1–6. doi:10.1080/14760584.2019.1557520.

- Wang B, Santoreneos R, Giles L, Haji Ali Afzali H, Marshall H. Case fatality rates of invasive meningococcal disease by serogroup and age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2019;37(21):2768–2782. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.04.020.

- Vyse A, Anonychuk A, Jakel A, Wieffer H, Nadel S. The burden and impact of severe and long-term sequelae of meningococcal disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013;11(6):597–604. doi:10.1586/eri.13.42.

- WHO. Defeating meningitis by 2030. 2021 [accessed 2022 Jan 24]. https://www.who.int/initiatives/defeating-meningitis-by-2030.

- Parikh SR, Campbell H, Bettinger JA, Harrison LH, Marshall HS, Martinon-Torres F, Safadi MA, Shao Z, Zhu B, von Gottberg A. The ever changing epidemiology of meningococcal disease worldwide and the potential for prevention through vaccination. J Infect. 2020;81(4):483–498. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.079.

- Aye AMM, Bai X, Borrow R, Bory S, Carlos J, Caugant DA, Chiou C-S, Dai VTT, Dinleyici EC, Ghimire P. Meningococcal disease surveillance in the Asia–Pacific region (2020): the global meningococcal initiative. J Infect. 2020;81(5):698–711. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.07.025.

- Lee EL, Puthucheary SD, Khoo BH, Thong ML. Purulent meningitis in childhood. Med J Malaysia. 1977;32:114–119.

- Lyn P, Pan Fui L. Management and outcome of childhood meningitis in east Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 1988;43:90–96.

- Choo KE, Ariffin WA, Ahmad T, Lim WL, Gururaj AK. Pyogenic meningitis in hospitalized children in Kelantan, Malaysia. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1990;10:89–98.

- Hussain IH, Sofiah A, Ong LC, Choo KE, Musa MN, Teh KH, Ng HP. Haemophilus influenzae meningitis in Malaysia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17(9 Suppl):S189–90.

- Raja NS, Parasakthi N, Puthucheary SD, Kamarulzaman A. Invasive meningococcal disease in the University of Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. J Postgrad Med. 2006;52(1):23–29; discussion 9.

- Nur H, Ibrahim J, Rohela M, Nissapatorn V. Bacterial meningtis: a five year (2001-2005) retrospective study at University Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2008;39:73–77.

- McNeil HC, Jefferies JM, Clarke SC. Vaccine preventable meningitis in Malaysia: epidemiology and management. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13:705–714.

- WHO. School immunization programme in Malaysia 24 February to 4 March 2008. 2008 [accessed 2022 Jan 6]. https://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/policies_strategies/Malaysia-school-immunization.pdf.

- Rohani MY, Ahmad Afkhar F, Amir MA, et al. Serogroups and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of Neisseria meningitidis isolated from army recruits in a training camp. Malays J Pathol. 2007;29(2):91–94.

- AlAzeri A. Meningococcal carriage among Hajjis in Makkah, 1421 H. Saudi Epidemiol Bull. 2002;9(1):3–4.

- Kuppusamy P. Thesis: distribution of serogroups and genotypes among Neisseria Meningitidis strains in Malaysia. 2009 [accessed 2022 Jan 6]. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/42994173.pdf.

- Ariza A, Rohani M, Ariza A. Neisseria meningitidis isolates with moderate susceptibility to penicillin. Med J Malaysia. 2004;59(4):558–559.

- Academy of Medicine Malaysia. Malaysian clinical practical guidelines on adult vaccination. 2003 [accessed 2022 Jan 6]. http://www.acadmed.org.my/view_file.cfm?fileid=283.

- Malaysian Society of Infectious Diseases & Chemotherapy. Guidelines for adult immunisation. 3rd ed. 2020 [accessed 2022 Jan 9]. https://adultimmunisation.msidc.my/.

- Goni MD, Naing NN, Hasan H, Wan-Arfah, N, Deris, ZZ, Arifin, WN, Baaba, AA. Uptake of recommended vaccines and its associated factors among Malaysian pilgrims during Hajj and Umrah 2018. Front Public Health. 2019;7:268.

- Ministry of Health – Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2020/1441H-Hajj and Umrah health regulations. Health requirements and recommendations for travelers to Saudi Arabia for Hajj and Umrah. 2020 Jan 14 [accessed 2022 Jan 6]. https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Hajj/HealthGuidelines/HealthGuidelinesDuringHajj/Pages/HealthRequirements.aspx.

- Ministry of Public Health Thailand. Division of epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. Annual Epidemiological Surveillance Report; 2019 [accessed 2021 July 8]. https://apps-doe.moph.go.th/boeeng/annual.php.

- Pancharoen C, Hongsiriwon S, Swasdichai K, et al. Epidemiology of invasive meningococcal disease in 13 government hospitals in Thailand, 1994-1999. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2000;31(4):708–711.

- Muangchana C, Chunsuttiwat S, Rerks-Ngarm S, Kunasol P. Bacterial meningitis incidence in Thai children estimated by a rapid assessment tool (RAT). Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2009;40:553–562.

- Batty EM, Cusack TP, Thaipadungpanit J, et al. The spread of chloramphenicol-resistant Neisseria meningitidis in Southeast Asia. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:198–203.

- WHO. Vaccination schedule for Thailand. 2022 [accessed 2022 Jan 6]. https://immunizationdata.who.int/pages/schedule-by-country/tha.html?DISEASECODE=MENINGOCOCCAL&TARGETPOP_GENERAL=.

- Department of Disease Control, Thailand. Meningococcal disease. [accessed 2022 Jan 6]. https://ddc.moph.go.th/disease_detail.php?d=19.

- Borrow R, Lee JS, Vazquez JA, Enwere G, Taha MK, Kamiya H, Kim HM, Jo DS. Meningococcal disease in the Asia-Pacific region: findings and recommendations from the Global Meningococcal Initiative. Vaccine. 2016;34(48):5855–5862.

- Manual of procedures for the philippine integrated disease surveillance and response. 3rd ed. National Epidemiology Center Department of Health; 2014 Apr [accessed 2021 July 9]. https://doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/publications/PIDSRMOP3ED_VOL1_2014.pdf.

- Meningococcal Disease. Monthly surveillance report No. 6. January 1 to June 29, 2019. Epidemiology Bureau Public Health Surveillance Division. Republic of the Philippines Department of Health; [accessed 2021 July 9]. https://doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/statistics/2019%20Meningococcal%20Disease%20Monthly%20Surveillance%20Report%20No.%206.pdf.

- Raguindin PF, Rojas VM, Lopez AL. Meningococcal disease in the Philippines: a systematic review of the literature. Abstract 0365 19th International Congress on Infectious Diseases (ICID); 2020; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. p. 149–150.

- Jaramillo-Fabay X. Terror in the air: meningococcal disease outbreak in the Philippines. Pediatr Infect Dis Soc Philippines. 2007;10(1):17–25.

- Gonzales ML, Bianco V, Vyse A. Meningococcal carriage in children and young adults in the Philippines: a single group, cross-sectional study. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145:126–132.

- Expanded Program on Immunization. Republic of the Philippines Department of Health. [accessed 2021 July 10].

- WHO. Meningococcal disease in the Philippines - 2005 update. [accessed 2022 Jan 7]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2005_01_19a-en.

- Decision N 975/QĐ-BYT of Ministry of Health on 29 March 2012 [in Vietnamese]. [accessed 2022 Jan 7]. http://www.bvmatbinhdinh.vn/pages/2010/documents/2012/boyte/QD.975.2012.BYT.PDF.

- WHO. Control of epidemic meningococcal disease: WHO practical guidelines. 2nd ed. WHO/EMC/BAC/98.3; 1998 [accessed 2022 Jan 7]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/64467.

- Oberti J, Hoi NT, Caravano R, Tan CM, Roux J. An epidemic of meningococcal infection in Vietnam (southern provinces). Bull World Health Organ. 1981;59:585–590.

- Vietnam health statistics yearbook 2018 [in Vietnamese]. [accessed 2022 Jan 7]. https://moh.gov.vn/documents/176127/0/NGTK+2018+final_2018.pdf/29980c9e-d21d-41dc-889a-fb0e005c2ce9.

- Van CP, Nguyen TT, Bui ST, Nguyen TV, Tran HTT, Pham DT, Trieu LP, Nguyen MD. Invasive meningococcal disease remains a health threat in Vietnam people’s army. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:5261–5269.

- Kim SA, Kim DW, Dong BQ, Kim JS, Anh DD, Kilgore PE. An expanded age range for meningococcal meningitis: molecular diagnostic evidence from population-based surveillance in Asia. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:310.

- Anh DD, Kilgore PE, Kennedy WA, Nyambat B, Long HT, Jodar L, Clemens JD, Ward JI. Haemophilus influenzae type B meningitis among children in Hanoi, Vietnam: epidemiologic patterns and estimates of H. Influenzae type B disease burden. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74(3):509–515.

- Phan T, Ho N, Vo D, Pham H, Ho T, Nguyen H, Nguyen TV. Abstract 0357. Characterization of Neisseria meningitidis in Vietnam from 1980s–2019. International Congress on Infectious Diseases 2020. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:120–158.

- Phan CH, Nguyen TPT, Doan UY, Nguyen TA, Thollot Y, Nievera MC. Safety of a quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy subjects aged 9 months to 55 years in Vietnam. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28:515–520.

- VUFO-NGO Resource Centre. 160,000 doses of meningococcal vaccine to be available in Vietnam next month. [accessed 2022 Jan 10]. https://www.ngocentre.org.vn/vi/news/160000-doses-meningococcal-vaccine-be-available-vietnam-next-month.

- Serra L, Presa J, Christensen H, Trotter C. Carriage of Neisseria meningitidis in low and middle income countries of the Americas and Asia: a review of the literature. Infect Dis Ther. 2020;9:209–240.

- Caugant DA, Maiden MC. Meningococcal carriage and disease–population biology and evolution. Vaccine. 2009;27:B64–70.

- WHO. Immunization analysis and insights. Surveillance for Vaccine Preventable Diseases (VPDs); 2017 [accessed 2021 July 19]. https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/immunization-analysis-and-insights/surveillance/surveillance-for-vpds.

- WHO. Defeating meningitis by 2030. Baseline Situation Analysis; 2019 [accessed 2021 July 15]. https://www.who.int/initiatives/defeating-meningitis-by-2030.