ABSTRACT

Penile cancer is a rare malignant disease. Paclitaxel combined with platinum is often used as a first-line chemotherapeutic regimen for late-stage penile cancer, and there is no standard second-line treatment. Clinical trials of immunotherapy for penile cancer are ongoing. There are no reports on PD1 inhibitor treatment in metastatic penile carcinoma patients with MMR/MSI status heterogeneity. A 68-year-old patient was hospitalized with bilateral inguinal lymph node metastasis and local penile recurrence after penile cancer surgery. The lesion of the right inguinal lymph node showed a mismatch-repair-deficient (dMMR)/microsatellite instability-low (MSI-L) status. After 3 cycles of sintilimab (a PD1 inhibitor) combined with paclitaxel and cisplatin, the partial response of the tumor was evaluated. Subsequently, sintilimab monotherapy was used as maintenance treatment for 2 months. However, The lesion of local penile recurrence showed mismatch repair proficient (pMMR)/microsatellite stability (MSS) status by secondary biopsy when progressed rapidly. Interestingly, after continued treatment with sintilimab combined with gemcitabine, the patient achieved a partial response again. We should be aware of the importance of secondary biopsy for different lesions to confirm the heterogeneity of MMR/MSI status. For penile cancer patients with MMR/MSI status heterogeneity, PD1 inhibitors combined with chemotherapy are safe and effective. Due to oligometastatic lesion progression caused only by the heterogeneity of MMR/MSI status, PD1 inhibitor cross-line therapy can also be considered an appropriate treatment.

Background

Penile cancer is a rare malignancy in Western countries. It accounts for under 1% of cancers in men in the United States, with approximately 2200 new cases and 420 deaths occurring in 2020. Penile cancer is more common in less developed areas of the world, such as Africa, Asia, and South America. In these areas, penile cancer can account for up to 10% to 20% of all malignancies in men. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) accounts for 95% of penile cancers. Management of penile carcinoma depends on the stage of the tumor at the time of diagnosis. Surgical treatment is the primary treatment for patients with early-stage disease, and neoadjuvant therapy or systemic therapy is the main treatment for locally advanced disease or patients with metastatic penile cancer who are ineligible for surgery. Paclitaxel combined with platinum is often used as a first-line chemotherapeutic agent. However, patients whose metastatic penile carcinoma progresses or recurs after front-line cisplatin-based chemotherapy experience poor responses to the available salvage treatments, with a median overall survival time of <6 months.Citation1 After the failure of the first-line treatment, there is no standard second-line treatment. Due to the low incidence of penile cancer, immunotherapy-related clinical trials are still ongoing. Nevertheless, PD-1 inhibitors can be considered for the treatment of penile cancers with microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair-deficient (dMMR) status, according to NCCN guidelines. However, there have been no reports on penile cancer patients with dMMR/MSI-H status heterogeneity or treatment models after the development of immune resistance to therapy.

We present the case of a patient with metastatic penile carcinoma with MMR/MSI status heterogeneity who was treated with sintilimab plus chemotherapy and achieved an excellent response. Thus, after oligometastatic lesion progression, cross-line immunotherapy still provides therapeutic benefits.

Case presentation

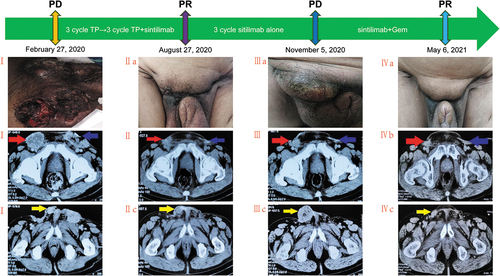

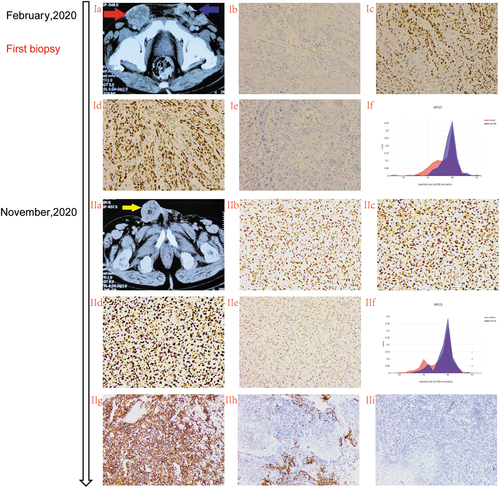

A 68-year-old male patient with no past medical history was originally diagnosed with moderate to poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the penis in 2018. He underwent partial penectomy with lymph node dissection without adjuvant therapy. In February 2020, he experienced local recurrence (named lesion C) (Ic) and bilateral inguinal lymph node metastases with a palpable fixed inguinal nodal mass (named lesions A and B) (stage IV T×N3M0 AJCC 8th) (Ib). The metastatic lymph nodes were pathologically confirmed to be squamous cell carcinoma. The patient’s HPV status was unknown. Thereafter, he received 3 cycles of chemotherapy with paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, q3 W) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2, q3 W). Three weeks later, a pelvic computed tomography was performed to assess tumor progression according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. Meanwhile, Lesion A was confirmed to have a mismatch-repair-deficient (dMMR) status (loss of MLH1 and PMS2 protein expression) by immunohistochemistry (Ib–Ie). Beginning 20 May 2020, the patient was administered the original chemotherapy regimen combined with sintilimab (200 mg, q3w) for 3 cycles. Subsequently, the bilateral inguinal lymph node metastases were significantly reduced in size and considered healed without serious treatment-related adverse events. Partial response was assessed in lesion A and lesion B on 27 August 2020 (IIa–IIc). Subsequently, the patient received maintenance monotherapy treatment with sintilimab. In November 2020, after 3 cycles and 3 months of disease control, the pelvic computed tomography scan showed a dimensional increase in lesion C (20 mm vs. 55 mm) (IIIa,IIIc), which was rebiopsied and displayed a mismatch-repair-proficient (pMMR) status (IIb–IIe). Based on the rareness of this finding, the different areas were macrodissected and tested separately for MSI and TMB by next-generation sequencing (NGS) to confirming the previous immunohistochemistry (IHC) results. Surprisingly, Lesion A showed MSH-L status with MLH1 mutation, while lesion C showed MSS with a high tumor exonic mutational burden (TMB) (14.2 mutations/megabase) (,IIf). Meanwhile, the Lesion C had a PD-L1 tumor proportion score 60% and combined positive score 70 (clone 22C3)(IIg–IIi). On 16 June 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted accelerated approval of pembrolizumab for the treatment of adult and pediatric patients with unresectable or metastatic tumor mutational burden-high (TMB-H) [>10 mutations/megabase (mut/Mb)] solid tumors, as determined by an FDA-approved test, following progression after prior treatment and when no satisfactory alternative treatment options are available.Citation2 Therefore, the patient was treated with sintilimab combined with gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2, d1,8, q3w) and achieved a partial response without serious treatment-related adverse events in May 2021 (Ⅳa–Ⅳc). The last treatment was in November 2021. By the time of submission, the patient was still in the process of follow-up.

Figure 1. Summary of patient treatment history.

Figure 2. Different lesions represented MMR heterogeneity during treatment.

Discussion

Penile squamous cell carcinoma (PSCC) is a rare disease. The primary treatment is surgical management for early-stage tumors. Systemic chemotherapy is the mainstay of therapy for locoregional and metastatic disease. In the era of immunotherapy, ongoing penile SCC-related phase 2 clinical trials evaluating PD-L1/PD-1 targeting for metastatic penile cancer patients who are unfit for or progress following platinum-based chemotherapy. Pembrolizumab (a PD-1 inhibitor) can be used for unresectable or metastatic, microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair-deficient (dMMR) tumors that have progressed following prior treatment and when no satisfactory alternative treatment options are available.Citation3,Citation4 As shown in our study, patients achieved a partial response and a longer remission time after treatment with a PD-1 inhibitor.

However, there are few reports regarding tumor MMR-MSI status heterogeneity among solid tumors, including penile squamous cell carcinoma. Here, we present a case report that offers a unique opportunity to discuss challenges and implications for the diagnostic approach and therapeutic management of this special subgroup.

Q1:

What are the causes of tumors with MMR/MSI status heterogeneity, and how can we confirm them?

In everyday practice, molecular markers vary between different areas, different metastatic lesions and over time, such as the K-ras mutation and Her-2 amplification status. Fotios Loupakis et al. presented the case of a patient with mCRC with MMR/MSI status heterogeneity in adjacent tumor areas.Citation5 This patient’s tumor heterogeneity was very similar to that of our reported patient. This phenomenon is caused by somatic mutations rather than germline mutations in mismatch repair-related genes, such as the MLH1 gene, which is similar to our case.

To confirm tumor MMR and MSI status heterogeneity, detection errors must be excluded. Camille Evrard et al. suggested using new and accurate methods such as microsatellites analyzed using next-generation sequencing (NGS) and analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) detection to confirm tumor MMR/MSI status heterogeneity. Here, to eliminate detection errors, MMR status was determined by two different methods, microsatellite instability (MSI) analysis using next-generation sequencing (NGS) and immunohistochemistry of the MMR proteins in the patient’s tumor tissue (as shown ).

Q2:

How can acquired immunotherapy resistance be solved in patients with MMR-MSI status heterogeneity?

Tumor heterogeneity results in the selection of tumor subclones that can escape antitumor immunity, leading to acquired resistance to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. Several clinical trials of combinations of immunotherapeutic agents with targeted agents, cytotoxic chemotherapy, and/or radiation are ongoing to overcome resistance to ICI therapy. No data exist concerning the dynamic evolution of MMR and MSI status during tumor progression, especially under treatment selection pressure. To date, no studies have been published regarding the efficacy of ICIs on tumors with MMR and MSI status heterogeneity. This represents a challenge in our tumor evaluation system and affects decisions regarding the withdrawal of immunotherapy after disease progression for patients with MMR-MSI status heterogeneity. Our patient achieved a partial response after immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy despite acquired resistance.

Q3:

Which biomarker can better predict the efficacy of immunotherapy for penile cancer?

For most solid tumors, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression is used as a predictor of the efficacy of immunotherapy, such as in lung cancer, gastric cancer, and esophageal cancer. PD-L1 expression as determined by the antibody clone 5H1 has been detected in 40–60% of penile SCC.Citation6 However, there is no standard process or cutoff value for PD-L1 expression detection in penile cancer. Sabina Davidsson et al. found that PD-L1 expression varied greatly in tumor cells using two different anti-PD-L1 antibodies (7.3% with antibody clone SP142 vs. 32.1% with antibody clone 28.8). In our case, the tumor had a PD-L1 tumor proportion score 60% and combined positive score 70 with antibody clone 22C3. In addition, the expression level of PD-L1 in tumor cells was different from that in tumor-infiltrating immune (TII) cells. PD-L1 expression is closely related to the clinicopathological features of penile cancer.Citation7 With the development of clinical trials of penile cancer and standardization of test methods, the detection of PD-L1 expression is expected to become the most promising predictor of immunotherapy efficacy.

Despite a lack of standardization of quantification and reporting systems, tumor mutational burden (TMB) is widely used as a predictor of the efficacy of immunotherapy. Recently, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of ICIs for patients with a TMB ≥10 mutation/megabase. This was also one of the reasons for not replacing immunotherapy in our case.

The FDA approved PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition treatment for any solid tumor showing MSI-H and/or defects in the MMR system. A few studies have reported that pembrolizumab produces an objective response in penile cancer patients with MSI-H status.Citation8 In addition, the detection methods of MMR status are standardized. Therefore, dMMR/MSI-H status is by far the most significant predictor of immunotherapy.

Conclusion

In our case, we emphasize the role of MMR/MSI status heterogeneity in tumor precision therapy and the significance of secondary puncture biopsy. Despite the lack of primary evidence for using immunotherapy for penile squamous cell carcinoma, chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy should be considered for penile squamous cell carcinoma with dMMR/MSI-L status.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the manuscript and are in agreement with the content. YY-D wrote the manuscript in consultation with XL-Z. YZ and WL-L conducted data collection. WQ-H, LZ and JZ revised the manuscript and directed the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

| dMMR | = | mismatch-repair-deficient |

| pMMR | = | mismatch repair proficient |

| MSI | = | microsatellite instability |

| TMB | = | tumour mutational burden |

| PD-1 | = | programmed cell death protein 1 |

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wang J, Pettaway CA, Pagliaro LC. Treatment for metastatic penile cancer after first-line chemotherapy failure: analysis of response and survival outcomes. Urology. 2015;85(5):1–4. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.12.049.

- Subbiah V, Solit DB, Chan TA, Kurzrock R. The FDA approval of pembrolizumab for adult and pediatric patients with tumor mutational burden (TMB) ≥10: a decision centered on empowering patients and their physicians. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(9):1115–18. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2020.07.002.

- Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, Skora AD, Luber BS, Azad NS, Laheru D, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500596.

- Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, Lu S, Kemberling H, Wilt C, Luber BS, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357(6349):409–13. doi:10.1126/science.aan6733.

- Loupakis F, Maddalena G, Depetris I, Murgioni S, Bergamo F, Dei Tos AP, Rugge M, Munari G, Nguyen A, Szeto C, et al. Treatment with checkpoint inhibitors in a metastatic colorectal cancer patient with molecular and immunohistochemical heterogeneity in MSI/dMMR status. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):297. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0788-5.

- Udager AM, Liu TY, Skala SL, Magers MJ, McDaniel AS, Spratt DE, Feng FY, Siddiqui J, Cao X, Fields KL, et al. Frequent PD-L1 expression in primary and metastatic penile squamous cell carcinoma: potential opportunities for immunotherapeutic approaches. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(9):1706–12. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdw216.

- Davidsson S, Carlsson J, Giunchi F, Harlow A, Kirrander P, Rider J, Fiorentino M, Andrén O. PD-L1 expression in men with penile cancer and its association with clinical outcomes. Eur Urol Oncol. 2019;2(2):214–21. doi:10.1016/j.euo.2018.07.010.

- Hahn AW, Chahoud J, Campbell MT, Karp DD, Wang J, Stephen B, Tu S-M, Pettaway CA, Naing A. Pembrolizumab for advanced penile cancer: a case series from a phase II basket trial. Invest New Drugs. 2021;39(5):1405–10. doi:10.1007/s10637-021-01100-x.