ABSTRACT

As infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae is an important cause of pneumonia in children, the World Health Organization recommends childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs). In January 2017, PCV universal mass vaccination (UMV) was introduced in Poland for children aged <2 years. The objective of this study was to estimate and describe the trends in the incidences of various types of pneumonia hospitalizations in Poland before (2013–2016) and after (2017–2018) introduction of the UMV program. The study was conducted at the regional hospitals of Opole and Bialystok and included all hospitalized children aged <2 years with a primary or secondary diagnosis of pneumonia in their electronic medical records. Pneumonia diagnoses were identified based on International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) codes for bacterial, viral, and other/unknown-cause pneumonias. The effect of the implementation of PCV UMV was modeled via an inferential multivariate model. Among 4,168 children included in the study, 64.3% were admitted before PCV UMV. The number of radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia cases varied between 55 and 176 cases per 100,000 person-years, and no trend was observed over time. However, inferential modeling showed statistically significant decreasing trends in the incidence rates of bacterial-coded pneumonia (28.48%), viral-coded pneumonia (35.36%), all-cause pneumonia (24.60%), and radiograph-confirmed likely non-bacterial pneumonia (24.98%) among children eligible for UMV. This might be the first indication of the impact of the PCV UMV program in Poland.

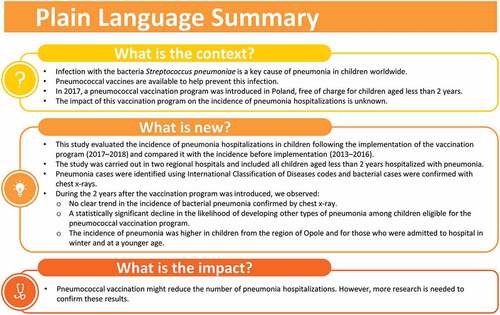

Plain Language Summary

What is the context?

Infection with the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae is a key cause of pneumonia in children worldwide.

Pneumococcal vaccines are available to help prevent this infection.

In 2017, a pneumococcal vaccination program was introduced in Poland, free of charge for children aged less than 2 years.

The impact of this vaccination program on the incidence of pneumonia hospitalizations is unknown.

What is new?

This study evaluated the incidence of pneumonia hospitalizations in children following the implementation of the vaccination program (2017-2018) and compared it with the incidence before implementation (2013-2016).

The study was carried out in two regional hospitals and included all children aged less than 2 years hospitalized with pneumonia.

Pneumonia cases were identified using International Classification of Diseases codes and bacterial cases were confirmed with chest x-rays.

During the 2 years after the vaccination program was introduced, we observed:

No clear trend in the incidence of bacterial pneumonia confirmed by chest x-ray.

A statistically significant decline in the likelihood of developing other types of pneumonia among children eligible for the pneumococcal vaccination program.

The incidence of pneumonia was higher in children from the region of Opole and for those who were admitted to hospital in winter and at a younger age.

What is the impact?

Pneumococcal vaccination might reduce the number of pneumonia hospitalizations. However, more research is needed to confirm these results.

Introduction

Infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) is a major cause of pneumonia in children worldwide.Citation1 This bacterium represents a major global public health problem and is also responsible for other conditions, including meningitis, otitis media, sinusitis, bronchitis and febrile bacteremia.Citation2,Citation3 In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 294,000 deaths annually among children <5 years of age are caused by pneumococcal infections, with a further 23,300 deaths in children co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus.Citation4

To prevent S. pneumoniae infections, the WHO has recommended the inclusion of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) in childhood immunization programs worldwide since 2012.Citation4,Citation5 Currently, three PCVs are approved for use, which contain a variable number of antigens (7, 10 or 13): the 7-valent PCV (PCV7), the 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV) and the 13-valent PCV (PCV13).Citation6

In Poland, between 2007 and 2011, the number of children (aged 0–6 years) hospitalized due to bacterial pneumonia as identified by International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) codes increased from 3,822 to 11,466, which comprised 0.5% and 1.2% of all child hospitalizations, respectively.Citation7 Children aged 1–2 years were the most frequently hospitalized group.Citation7

Poland was one of the last countries in Europe to introduce PCV universal mass vaccination (UMV) free of charge.Citation8 Previously, vaccination was only available for high-risk patients and, since 2006, children in the Polish city of Kielce, where PCV7 was introduced free of charge in the vaccination schedule for children aged 5 years or younger.Citation9,Citation10 The vaccination rate in Kielce was around 99% and resulted in a significant decrease in the number of pneumonia-related hospitalizations in children during the first year the vaccine was made freely available.Citation9,Citation10 The greatest declines in admission rate and mortality were observed in children aged 2 years or younger, but declines were reported for all age groups, probably due to herd effects.Citation9,Citation10 Following the positive experience in Kielce, in January 2017 Poland introduced a PHiD-CV UMV program. All children born after 1st January 2017 were eligible to receive three doses of PHiD-CV on a 2–4–13-month schedule, up to 2 years of age.Citation8

Previous studies have evaluated pneumonia hospitalization rates and trends prior the introduction of the PHiD-CV into the UMV program in Poland; however, none of them explored these data following the inclusion of PHiD-CV.Citation7,Citation11 Here, we aimed to address this data gap by investigating the rates and trends of pneumonia hospitalizations following implementation of the PHiD-CV UMV program (2017–2018) and comparing the data with the pre-PHiD-CV UMV period (2013–2016). provides an overview of the context, novelty and impact of the current study in a form that could be shared with parents of young children.

Patients and methods

This observational study aimed to describe trends in the incidence of hospitalizations for pneumonia in children aged <2 years in Poland before (2013–2016) and after (2017–2018) the introduction of the PHiD-CV UMV program.

The study was conducted at the regional pediatric hospitals in the Polish cities of Opole and Bialystok, which are centralized treatment centers for all cases of pediatric pneumonia in their regions. They were selected based on their ability to identify eligible patients, experience in extraction and exportation of electronic medical records (EMRs), availability of data of interest (i.e., diagnosis codes, date and age), availability of chest radiographs and staff resources, including on-site radiologists and information technology personnel responsible for the EMR system.

The EMRs included patient-level data for demographics (i.e., month and year of birth and sex) and hospitalization details (i.e., primary and secondary diagnoses, admission and discharge dates). Pneumonia diagnoses were classified in the EMRs according to ICD-10 codes for bacterial pneumonia (J13–J15, J85.1, J86); viral pneumonia (J10.0, J11.0, J12); and other pneumonia (J16–J18) (details are provided in Table S1).Citation12 The UMV time period was defined according to the year of birth: all children born before 1st January 2017 were classified as children born during the pre-UMV period, while all children born on 1st January 2017 or later were classified as children born during the post-UMV period.

Objectives

The primary objective was to describe trends in the incidence of hospitalizations for radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia during the pre- and post-UMV periods. Secondary objectives were to describe trends in the incidences of hospital admissions for (1) ICD-10-coded bacterial pneumonia, (2) ICD-10-coded viral pneumonia, (3) ICD-10-coded all-cause pneumonia and (4) radiograph-confirmed likely non-bacterial pneumonia during the pre- and post-UMV periods.

Study population and sample size

The study included all children aged <2 years admitted to hospital with EMRs of interest and with a primary or secondary diagnosis of pneumonia (following ICD-10 codes) between 1st January 2013 and 31st December 2018. The sample size was expected to be approximately 550–750 hospitalizations per year.

Endpoints

A validation analysis (see Text S1) showed that only 18.1% of ICD-10-coded bacterial pneumonia were likely bacterial on radiograph review according to WHO guidelines,Citation13 but 87.5% of cases of ICD-10-coded non-bacterial pneumonia were likely non-bacterial on radiograph review. Based on this, the primary endpoint (hospitalizations for radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia) included all cases with ICD-10-coded bacterial pneumonia (J13–J15, J85.1, J86) classified as likely bacterial pneumonia based on radiographs. Secondary endpoints were defined as follows:

ICD-10-coded bacterial pneumonia hospitalizations (J13–J15, J85.1 or J86).

ICD-10-coded viral pneumonia hospitalizations (J10.0, J11.0 or J12).

ICD-10-coded all-cause pneumonia hospitalizations (J10.0, J11.0, J12–J18, J85.1 or J86).

Radiograph-confirmed likely non-bacterial pneumonia hospitalizations included all cases with ICD-10-coded non-bacterial pneumonia (J10.0, J11.0, J12 or J16–J18) and all cases with ICD-10-coded bacterial pneumonia (J13–J15, J85.1, J86) reclassified as likely non-bacterial based on radiographs.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC) and R software (R Core Team, 2013). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics (i.e., diagnosis date and sex) and hospitalization characteristics. Frequency tables were generated for categorical variables. Mean, median and standard deviation (SD) are provided for continuous data. It was assumed that all infants born in 2017 and later were vaccinated. The annual incidence rate of radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia was calculated as the total number of radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia cases divided by the person-years at risk (based on the number of births in the region during the preceding 24 months) and multiplied by 100,000.

For all endpoint definitions, the monthly incidence of pneumonia was modeled as a function of eligibility for the UMV program (inferential model) using a generalized mixed model (via SAS PROC GLIMMIX), with a negative binomial distribution and a log-link. The log of the eligible population (i.e., the number of births during the preceding 24 months) was used as the offset variable. In addition to eligibility for the UMV program, other factors that were adjusted for were age, region, admission seasonality, non-UMV time trends and seasonality of birth. A p-value of 0.05 (two-sided) was used to denote statistically significant results.

Changes in study conduct

The study was initiated at four study sites. However, two of these sites did not continue to participate due to contracting issues. Consequently, the study was based on data from two sites from the regions of Opole and Bialystok.

Regulatory and ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with all legal and regulatory requirements, including all applicable patient privacy requirements, Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices and the guiding principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by an ethics committee at each study site. Data privacy was ensured by using pseudonymized data.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

As shown in , a total of 4,168 children were included in the study, with a mean (SD) age at hospital admission of 9.1 (6.7) months and a higher proportion of males (60.8%) than females (39.2%). 64.3% of the children were admitted during the pre-UMV period (2013–2016).

Table 1. Characteristics of the children (aged <2 years) hospitalized with pneumonia in two Polish hospitals during 2013–2018.

Of the total admitted, 1,453 patients (34.9%) had an ICD-10 diagnosis code for bacterial pneumonia, 606 (14.5%) for viral pneumonia and 2,099 patients (50.4%) had pneumonia due to other or unspecified organisms. The most commonly recorded ICD-10 codes were J18 “Pneumonia, unspecified organism” in Opole and J15 “Bacterial pneumonia, not elsewhere classified” in Bialystok.

Information on the year of birth was missing for four patients, while non-pneumonia ICD-10 diagnosis codes (J10.1, J10.8 and J11.1) were listed for 10 patients (0.2%). These patients were excluded from the analyses; hence, 4,154 children were included.

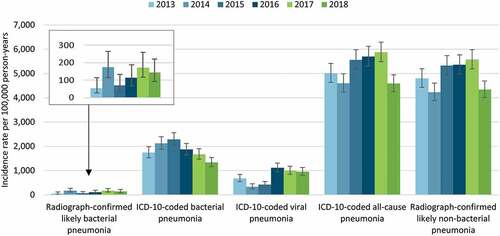

Primary endpoint (radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia)

A total of 98 radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia hospitalizations were observed during 2013 to 2018, 47 in Opole and 51 in Bialystok (Table S2). During the pre-UMV period, the incidence rate ranged from 55 to 176 per 100,000 person-years, while in the post-UMV period it was 174 and 144 per 100,000 person-years (Table S2). As shown in , the incidence rate did not exhibit a clear trend over time.

Figure 2. Incidence rate of pneumonia hospitalizations among children aged <2 years in two Polish cities by year (2013–2018).

To model the effect of implementing PHiD-CV in the UMV program, the incidence rate was modeled using an inferential model. The analysis showed that eligibility for UMV had no statistically significant effect on the incidence rate of radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia over time ().

Table 2. Estimated percentage change and effect of universal mass vaccination with 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine on the incidence rate of pneumonia hospitalizations among children aged <2 years in two Polish hospitals (inferential model).

Secondary endpoint (ICD-10-coded bacterial pneumonia)

There were 1,452 hospitalizations coded for bacterial pneumonia which were analyzed, 597 in Opole and 855 in Bialystok (Table S2). The incidence rate varied between 1,744 and 2,283 per 100,000 person-years during the pre-UMV period, and was lower (1,672 and 1,339 per 100,000 person-years) during the post-UMV period, visually indicating a declining trend (Table S2 and ).

Again, the incidence rate was modeled using an inferential model that included the same variables used to evaluate the primary outcome. The analysis showed that, after implementation of the UMV program, children were statistically significantly less likely to have ICD-10 coded bacterial pneumonia ().

Other secondary objectives

A total of 606 hospitalizations for viral-coded pneumonia was recorded between 2013 and 2018, 384 and 222 cases in Opole and Bialystok, respectively (Table S2). The overall incidence rate varied between 335 and 1,115 per 100,000 person-years during the pre-UMV period, while it remained stable during the post-UMV period (999 and 954 per 100,000 person-years) ().

As mentioned above, 4,154 hospitalizations coded for all-cause pneumonia were analyzed, 3,035 patients in Opole and 1,119 in Bialystok (Table S2). The incidence rate ranged from 4,596 to 5,702 per 100,000 person-years during the pre-UMV period, and was 5,878 and 4,587 per 100,000 person-years in 2017 and 2018, respectively (Table S2 and ).

For radiograph-confirmed likely non-bacterial pneumonia, a total of 3,928 hospitalizations were analyzed, 2,939 in Opole and 989 in Bialystok (Table S2). The overall incidence rate varied between 4,229 and 5,361 per 100,000 person-years in the pre-UMV period and was 5,574 and 4,339 per 100,000 person-years in the post-UMV years (Table S2 and ).

The results from the inferential model are shown in . For viral pneumonia, all-cause pneumonia and radiograph-confirmed likely non-bacterial pneumonia, eligibility for UMV was associated with a statistically significantly lower incidence of hospitalization.

For all pneumonia types analyzed in this study, the results from the inferential model showed that younger age, living in Opole and being admitted to hospital during the winter were factors statistically significantly associated with higher incidence (data not shown).

Discussion

Overall, for the 6-year period 2013–2018, 4,158 children aged <2 years hospitalized due to pneumonia were included in the study and data from 4,154 of them were analyzed. The most commonly recorded causes of pneumonia were ICD-10 diagnosis codes J18 “Pneumonia due to unspecified organisms” and J15 “Bacterial pneumonia, not elsewhere classified.” This code distribution is consistent with that observed in a recent comprehensive analysis that focused on pneumonia hospitalizations in Poland prior to the introduction of the PHiD-CV UMV program in 2017.Citation11 Surprisingly, these two ICD-10 codes were reported differently in the two participating regions, with Opole most frequently registering the ICD-10 code J18 (67.2%) and Bialystok the ICD-10 code J15 (76.2%), which suggests either inconsistent coding practicesCitation7 or a tendency to classify pneumonia as bacterial pneumonia based on clinical findings.Citation14 Currently, rapid and accurate techniques to identify the microbial etiology of pneumonia remain elusive despite advances in medical technology.

In the current study, the yearly incidence rate of radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia hospitalizations varied between 55 and 176 per 100,000 person-years during the period prior to PHiD-CV UMV implementation (i.e., 2013–2016). This incidence is substantially lower than the 512–586 per 100,000 person-years reported in Gajewska et al.’s 2009–2016 study of Polish children.Citation11 These differences could be related to (1) the methodology used to identify bacterial pneumonia-related hospitalizations; while Gajewska et al. used ICD-10 coding only, the present analysis also considered radiographs to define radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia cases, which has a higher specificity;Citation15 or (2) the wider coverage of hospitals in Gajewska et al.’s study (93% of the hospitals in Poland) than in the present study (two regions).Citation11

Overall, the incidence rate and number of radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia hospital admissions did not follow a clear trend, which might be due to the short observational period following PHiD-CV UMV implementation (i.e., 2017 and 2018). Although vaccination was estimated to cover 94% of children born in 2017,Citation11 at no point in the study period was the entire study cohort eligible for PHiD-CV vaccination. All children aged 2 years or less would only have become eligible for vaccination in 2019. In addition, the small number of radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia cases might be affected by the difficulty of retrospectively reviewing and classifying radiographs without any clinical context.

On the other hand, the inferential models showed statistically significant declining trends among children eligible for PHiD-CV UMV in the incidence rates of bacterial-coded pneumonia, viral-coded pneumonia, all-cause pneumonia and radiograph-confirmed likely non-bacterial pneumonia.

Regarding the differences between regions, the incidence rates of bacterial-coded pneumonia were variable, remaining stable in Bialystok but decreasing in Opole. This could be explained by possible geographic variations in coding practices and vaccination coverage. Living in Bialystok was a factor statistically significantly associated with lower incidence of all pneumonia types analyzed in this study. Seasonality was another predictor for all pneumonia types analyzed in this study, with increased hospital admission rates in winter, a well-known factor reported in previous studies.Citation16,Citation17

Study limitations and strengths

The present study has several limitations. First, the post-UMV period analyzed (i.e., 2 years) might be too short to observe any significant trends. As stated above, at no point in the study period was the entire study cohort eligible for PHiD-CV vaccination. The study used previously collected medical data available in an electronic format in the hospital records. We did not contact the parents/guardians and we did not ascertain the vaccination status of the children. In addition, just two regions of Poland were included in the study; therefore, the results observed might not be generalizable to other jurisdictions in Poland or to other countries. Radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia cases were confirmed from radiographs; we did not assess other clinical data (e.g., body temperature) or microbiological investigations that might have provided a more accurate clinical diagnosis. Also, as it is inherent to this type of study, any observed trend could reflect changes in medical practice, access to healthcare or in the use of ICD-10 diagnosis codes. Finally, the selection of cases was made based on the ICD-10 diagnosis code given at the time of admission and discharge; as hospital coding processes can be influenced by both medical and non-medical factors, the final discharge codes may not fully reflect the actual diagnosis.

Despite these limitations, the present study also has several strengths. First, this is the first study to analyze rates and trends of pneumonia hospitalizations following implementation of the PHiD-CV UMV program in Poland. Second, the retrospective approach based on extraction of data from EMRs minimized selection bias, as all cases matching the selection criteria were included. Finally, as the use of ICD-10 diagnosis codes can be influenced by both medical and non-medical factors, we undertook a validation analysis to assess how accurately bacterial and non-bacterial pneumonia ICD-10 codes reflected chest radiographs. Based on the results of this analysis, all radiographs for pneumonia cases with bacterial ICD-10 codes were reviewed and assessed based on the WHO diagnosis criteria.Citation13

Conclusion

After 2 years of PHiD-CV UMV implementation in Poland, no trend was observed in the evolution of the incidence rate of radiograph-confirmed likely bacterial pneumonia hospitalizations. However, in the inferential models, a statistically significant downward trend was observed for bacterial-coded, viral-coded, all-cause and radiograph-confirmed likely non-bacterial pneumonia among children eligible for PHiD-CV UMV, which may represent the first sign of an impact of this program. Lower age, living in Opole and being admitted to hospital during winter were significantly associated with higher incidence for all types of pneumonia. Further research, involving larger geographic areas and with a longer post-UMV observation period, would be helpful for deriving more conclusive observations.

Abbreviations

| CI | = | confidence interval |

| EMR | = | electronic medical record |

| ICD-10 | = | International Classification of Diseases 10th revision |

| PCV | = | pneumococcal conjugate vaccine |

| PCV7 | = | 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine |

| PCV13 | = | 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine |

| PHiD-CV | = | 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine |

| SD | = | standard deviation |

| S. pneumoniae | = | Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| UMV | = | universal mass vaccination |

| WHO | = | World Health Organization |

Author contributions

All authors participated in the design or implementation or analysis and interpretation of the study; and in the development of this manuscript and in its critical review with important intellectual contributions. All authors had full access to the data and gave approval before submission. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The work described was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors for conduct, reporting, editing and publication of scholarly work in medical journals.

Data sharing statement

GSK makes available anonymized individual participant data and associated documents from interventional clinical studies which evaluate medicines, upon approval of proposals submitted to www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. To access data for other types of GSK sponsored research, for study documents without patient-level data and for clinical studies not listed, please submit an enquiry via the website.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (154.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (170.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Monica Tafalla, Dominique Rosillon, Alicja Ksiazek and Meheni Khellaf (all GSK employees at the time the study was conducted), as well as Dara Stein (Evidera), for their contribution to the study design and/or protocol; Patricia Izurieta and Attila Mihalyi (GSK) for their contribution to the interpretation of the results; Ranjeetha Noorithaya (GSK) for data management; Sofia Fernandes and Barbara Gomez (PPD/Evidera) for project management; and Nikola Bulow (GSK) for technical writing of the study protocol. The authors would also like to thank Business & Decision Life Sciences platform for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination, on behalf of GSK. Leire Iralde Lorente (Business & Decision Life Sciences, on behalf of GSK) provided medical writing support.

Disclosure statement

AB and RD are employed by GSK. AB holds shares in GSK. EB is a consultant working on behalf of GSK. JZ declares he has received personal fees from GSK for the submitted work. AW declares that she took part as principal investigator in clinical studies for Pfizer, outside the submitted work. DS and CC are employees of PPD, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific (Evidera at the time of the study conduct), a contract research organization which received fees from GSK for performing the submitted work (data collection and statistical analysis), and which receives fees from multiple clients from the pharmaceutical industry for performing other scientific studies. JW declares having received grant from GSK for the submitted work. JW also declares having received honoraria for clinical trials and support for attending meetings from Pfizer, honoraria for advisory boards and lectures from GSK and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. The authors declare no other financial and non-financial relationships and activities.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2128566

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sattar SBA, Sharma S. Bacterial pneumonia. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing;2021[accessed 2022 Jun 13]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513321/ .

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal disease (Streptococcus pneumoniae). 2020 [accessed 2021 July 29]. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/diseases/pneumococcal-disease-streptococcus-pneumoniae .

- World Health Organization. Pneumococcal disease. 2021 [accessed 2021 July 28]. https://www.who.int/teams/health-product-and-policy-standards/standards-and-specifications/vaccine-standardization/pneumococcal-disease .

- World Health Organization.Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in infants and children under 5 years of age: WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2019;94:1–7 .

- WHO Publication.Pneumococcal vaccines WHO position paper – 2012 – recommendations. Vaccine. 2012;30(32):4717–18. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.093 .

- World Health Organization. Information sheet – observed rate of vaccine reactions – pneumococcal vaccine. 2012 [accessed 2021 Jul 30]. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/pvg/global-vaccine-safety/pneumococcal-vaccine-rates-information-sheet.pdf .

- Gajewska M, Lewtak K, Scheres J, Albrecht P, Goryński P. Trends in hospitalization of children with bacterial pneumonia in Poland. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2016;24(3):188–92. doi:10.21101/cejph.a4164 .

- Polish National Institute of Public Health. National Institute of Hygiene – National Research Institute. Vaccinations. Pneumococcal vaccine. [accessed 2022 March 07]. https://szczepienia.pzh.gov.pl/szczepionki/pneumokoki/ .

- Patrzalek M, Gorynski P, Albrecht P. Indirect population impact of universal PCV7 vaccination of children in a 2 + 1 schedule on the incidence of pneumonia morbidity in Kielce, Poland. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31(11):3023–28. doi:10.1007/s10096-012-1656-0 .

- Patrzałek M, Albrecht P, Sobczynski M. Significant decline in pneumonia admission rate after the introduction of routine 2+1 dose schedule heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) in children under 5 years of age in Kielce, Poland. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29(7):787–92. doi:10.1007/s10096-010-0928-9 .

- Gajewska M, Goryński P, Paradowska-Stankiewicz I, Lewtak K, Piotrowicz M, Urban E, Cianciara D, Wysocki MJ, Książek A, Izurieta P. Monitoring of community-acquired pneumonia hospitalisations before the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine into Polish National Immunisation Programme (2009–2016): a nationwide retrospective database analysis. Vaccine. 2020;38(2):194–201. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.031 .

- ICD10Data.com. Influenza and pneumonia. [accessed 2022 July 7]. https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/J00-J99/J09-J18 .

- Department of vaccines and biologicals. World Health Organization (WHO). Standardization of interpretation of chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children. 2001 [accessed 2021 July 15]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/66956/WHO_V_and_B_01.35.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.%20Accessed%2018%20September%202018 .

- Beckman KD. Coding common respiratory problems in ICD-10. Fam Pract Manag. 2014;21:17–22 .

- Hansen J, Black S, Shinefield H, Cherian T, Benson J, Fireman B, Lewis E, Ray P, Lee J. Effectiveness of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children younger than 5 years of age for prevention of pneumonia: updated analysis using World Health Organization standardized interpretation of chest radiographs. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(9):779–81. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000232706.35674.2f .

- Cilloniz C, Ewig S, Gabarrus A, Ferrer M, Puig de la Bella Casa J, Mensa J, Torres A. Seasonality of pathogens causing community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology. 2017;22(4):778–85. doi:10.1111/resp.12978 .

- Lin HC, Lin CC, Chen CS, Lin HC. Seasonality of pneumonia admissions and its association with climate: an eight-year nationwide population-based study. Chronobiol Int. 2009;26(8):1647–59. doi:10.3109/07420520903520673 .