ABSTRACT

COVID-19 appears to put people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA) at a higher risk of catastrophic consequences and mortality. However, investigations on the hesitancy and vaccination behavior of PLWHA in China were lacking compared to the general population. From January 2022 to March 2022, we conducted a multi-center cross-sectional survey of PLWHA in China. Logistic regression models were used to examine factors associated to vaccine hesitancy and COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Among 1424 participants, 108 participants (7.6%) were hesitant to be vaccinated while 1258 (88.3%) had already received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Higher COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was associated with older age, a lower academic level, chronic disease, lower CD4+ T cell counts, severe anxiety and despair, and high perception of illness. Lower education level, lower CD4+ T cell counts, and significant anxiety and depression were all associated with a lower vaccination rate. When compared to vaccinated participants, those who were not hesitant but nevertheless unvaccinated had a higher presence of chronic disease and lower CD4+ T cell count. Tailored interventions (e.g. targeted education programs) based on these linked characteristics were required to alleviate concerns for PLWHA in promoting COVID-19 vaccination rates, particularly for PLWHA with lower education levels, lower CD4+ T cell counts, and severe anxiety and depression.

Introduction

A growing body of research suggests that people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) who contract SARS-CoV-2 are more likely to require hospitalization and have poor clinical outcomes than people who do not have HIV/AIDS.Citation1 However, in terms of vaccine effectiveness, COVID-19 vaccines provide the same benefits to PLWHA as they do to everyone else.Citation2 As a result, ensuring vaccination coverage can mitigate the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on PLWHA to some extent. People living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA) should not be excluded from COVID-19 vaccine access plans regardless of their immune status, and nations should prioritize PLWH COVID-19 vaccination based on their epidemiological setting.Citation3 Despite considerable experimental evidence of the benefits of COVID-19 vaccinations for PLWHA, vaccine hesitancy remains one of the ten threats to global health.Citation4 Because PLWHA have compromised immune function, they are especially concerned about the possible harm of the COVID-19 vaccinations to their immune system.Citation5 According to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Novel Coronavirus Vaccine Technical Guide (First Edition), vaccination is recommended for inactivated and recombinant subunit vaccines, while for adenovirus vector vaccines, individuals should be fully informed and weigh the benefits against the risks.Citation6 However, as the only strategy of preventing viral infections and providing long-term immunity,Citation7 vaccines should be extensively distributed in order to build herd immunity. However, receiving the COVID-19 vaccines is critical for PLWHA, since studies has shown that immunological weakness is a risk factor for severe COVID-19 in people living with HIV.Citation8

According to the World Health Organization, COVID-19 vaccines have been tested in large, randomized controlled studies with persons of all ages, genders, nationalities, and those with known medical disorders. The vaccines have demonstrated great efficiency across all demographics and have been confirmed to be safe and effective in people with a variety of underlying medical disorders linked with an elevated risk of serious diseases.Citation9 On this basis, several researchers have undertaken specific trials for them to examine the true effects of the vaccines in order to eradicate the fear of COVID-19 vaccines among PLWHA. We found that most of the previous studies were in support of vaccines being delivered to PLWHACitation10–12 in the context of sustained antiretroviral therapy and a two-dose series of immunizations.Citation12

Countries have done numerous willingness surveys based on their national situations in order to thoroughly explore the hesitancy of PLWHA to be vaccinated. A French study followed up on 237 HIV-infected patients for treatment, and 68 (28.7%) participants declared their hesitancy to be vaccinated against COVID-19.Citation13 Some studies found a link between sociodemographic characteristics and vaccination willingness. A systematic review and meta-analysis found lower vaccination intentions among women than that in men.Citation14

According to the available literature, the majority of the studies in China to investigate the willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 were conducted on healthy people in the provinces where the experimental teams were situated, with little attention devoted to the PLWHA population. However, given that the PLWHA population has been documented to be one of the high-risk populations when infected with COVID-19, vaccination willingness of the PLWHA population should not be overlooked. Furthermore, most earlier studies only focused on vaccination willingness and its affecting factors, with few studies focusing on vaccination behavior because the vaccination rate was relatively low when the vaccine was first introduced, particularly for PLWHA.Citation15,Citation16

In this study, we aimed to investigate vaccination hesitancy and vaccination rate among PLWHA two years after the outbreak of COVID-19 in China from January to March 2022. We not only investigated vaccination hesitancy and vaccination rate among PLWHA but we also compared the findings to studies performed during periods of low vaccination rates in order to investigate factors related to vaccination intentions among PLWHA at different point in time. This survey looked at sociodemographic characteristics, physical health conditions and conditions related to HIV infection (such as the presence of chronic disease conditions, CD4+T cell count in the most recent episode of testing and exercising situation, an so on), mental health conditions (such as self-reported anxiety and depression) and brief illness perception.

Methods

Study design, participants, and sampling

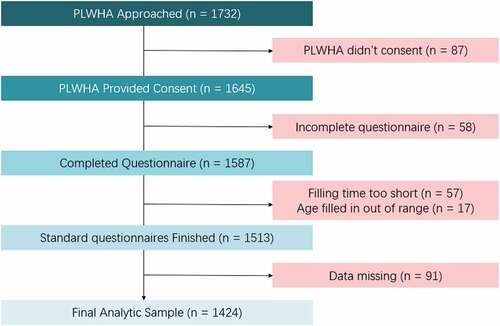

This was a multi-center hospital-based cross-sectional study of PLWHA on the Chinese mainland. To choose participants, we used a multistage sampling strategy. In the first stage, we separated mainland China into three regions (eastern, central, and western). Each region of mainland China had one province chosen at random, namely Beijing (eastern region), Shanxi (central region), and Guizhou (western region), respectively. In the second stage, we randomly chose one city from each province and designated institutions for PLWHA antiretroviral therapy service, namely the Fifth Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital (Fengtai), the Fourth People’s Hospital of Datong (Datong) and Guiyang Public Health Clinical Center (Guiyang). At the third stage, PLWHA who were treated in these three designated medical institutions were selected from January 2022 to March 2022 through convenient sampling. The study’s inclusion criteria were PLWHA aged above 18 who have been diagnosed with HIV/AIDS and were being treated at the designated institutions. The exclusion criteria were participants with severe mental illnesses who were unable to communicate. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University (IRB00001052–22008) and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Among 1732 participants approached, 1587 participants completed the questionnaire, with a response rate of 91.6%. We removed 57 participants with insufficient filling time, 17 participants who were outside the required age range, and 91 participants with data missing, yielding 1424 participants included in the final analysis ().

Recruitment and data collection

On a regular basis, PLWHA went to designated medical institutions to obtain HIV/AIDS follow-up services. The Fifth Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, the Fourth People’s Hospital of Datong and the Guiyang Public Health Clinical Center were designated as institutions in charge of PLWHA treatment. In China, the appointments and COVID-19 vaccinations were available at community health service center. Individuals were vaccinated in voluntary. The investigators in this study were trained outpatient medical professionals in these three hospitals who were knowledgeable with PLWHA. They explained the purpose and procedures of the study, answered queries about privacy protection, and recruited participants. PLWHA were invited to participate in the study throughout the follow-up process. The anonymous questionnaire was self-administered by participants using an online questionnaire collection platform (specifically Wen Juan Xing) under the introduction and interpretation of trained outpatient medical personnel. In order to thoroughly ensure the anonymity of the study, questionnaires were completely self-administered, including clinical data. However, convenient electronic medical record made it possible for the patients to timely refer to whenever they were uncertain about the questions, and investigators could offer to help at any time.

Vaccine hesitancy and uptake

The primary outcomes of this study are the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy rate and vaccination rate. The question “Do you think people living with HIV/AIDS should be vaccinated against COVID-19?” was used as a proxy to collect the participants’ hesitancy to COVID-19 vaccination; the response categories were as follows: should, uncertain, and should not. The hesitancy rate is the proportion of participants that answered “uncertain” or “should not” out of all participants. To assess the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines, we asked “Have you been vaccinated against COVID-19?.” Participants could select between “Yes” and “No.” We did not further explore the dose of COVID-19 vaccines they have vaccinated for those who responded “Yes.” The uptake rate is the proportion of participants who chose “Yes” out of all participants. However, it should be noted that participants who were vaccinated were automatically labeled as not hesitant, regardless of their “hesitancy” option.

Related factors

Based on prior studies,Citation17–19 we investigated information including sociodemographic characteristics, basic health conditions, HIV infection characteristics, and illness perception. Sociodemographic characteristics included gender, age, nationality, marital status, educational background, and economic level. Basic health conditions included chronic disease history, physical activity level, HIV/AIDS improvement according to the doctors, self-reported anxiety, self-reported depression, and self-reported general health condition. To study chronic conditions, we used “Have you been told by your doctor that you have a chronic disease (for example, hypertension, diabetes, cardiopathy, anemia, stroke and cerebrovascular diseases, viral hepatitis, dyslipidemia.)?.” For anxiety, participants could select one of six levels to do a quick emotional self-evaluation, with “No” “Little” “Moderate” “Severe” “Very severe” “Extremely severe”, and “Never” “Seldom” “Sometimes” “Much time” “Most of the time” “All the time” for depression. The last three options were merged into one group, “Severe or above” and “Much time or above” respectively. Similarly, participants might score their overall health as “Excellent” “Very good” “Good” “Moderate” or “Bad.” Physical activities level was measured according to the Physical Activity Rating Scale (PARS-3). Characteristics related to HIV infection included time since HIV diagnosis, CD4+ T cell count in the most recent episode of testing, and HIV infection routes. The CD4+ T cell count in the most recent episode of testing was assessed and documented using flow cytometry. In this study, illness perception was evaluated by the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ) for HIV/AIDS, which was a universal measure to assess the participants’ perceptions of current illness.Citation20,Citation21 The B-IPQ consisted of eight multiple choice items and one open-ended question about the etiology of the participants’ illness. The eight items were as follows (1) consequences (how much does your illness affect your life), (2) timeline (how long do you think your illness will continue), (3) personal control (how much control do you feel they have over your illness), (4) treatment (how much do you think their treatment can help your illness), (5) identity (how much do you experience symptoms from your illness), (6) concern (how concerned are you about your illness), (7) comprehension (how well do you feel that you understand their illness), (8) emotion (how much does your illness affect you emotionally). Each item was scored ranging from 0 to 10. Except for question 3, 4, and 7, greater scores indicated a higher level of negative attitude perception (reversed scored). The B-IPQ total score varied from 0 to 80, with higher scores indicating more negative illness perceptions. By tertile, We divided the B-IPQ score into three groups (low, mediate, and high).

Statistical analysis

The overall vaccine hesitancy rate, vaccination rate, and the rates in specific characteristic populations were all calculated. The Chi-square test was used to compare the different distributions of vaccine hesitancy rate and vaccination rate among specific characteristic populations based on sociodemographic characteristics, HIV infection conditions, general health condition, subjective psychological status, and illness perception. The multivariable models included relevant components with p-values less than 0.05 in the Chi-square test. We utilized multivariable logistic regression models to investigate factors associated with vaccine hesitancy and vaccination rates, respectively. We calculated adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% CIs, and obtained forest plots. Furthermore, we used a multivariable logistic regression model among the participants who were not hesitant to take COVID-19 vaccine, to examine factors associated with PLWHA who were not hesitant but remained unvaccinated (NU), versus those who were vaccinated. In the sensitivity analysis, the missing values were filled by multiple imputation method to test the robustness of the results. A p < .05 was the threshold for statistical significance. R 4.1.2 were used in the statistical analysis and statistical mapping.

Results

Basic characteristics

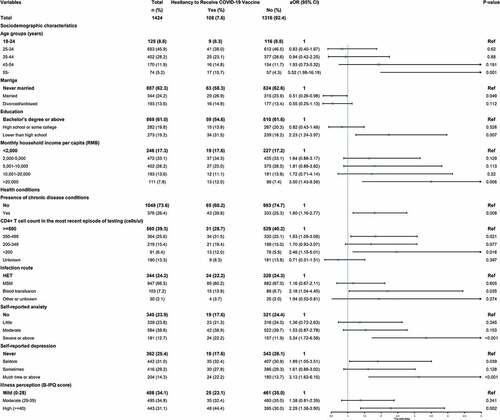

The majority of the 1424 participants were male (n = 1295, 90.9%), between the ages of 18 to 44 (n = 1180, 82.9%), currently single (n = 887, 62.3%), were from Han group (n = 1245, 87.4%), and held a bachelor’s degree or above (n = 869, 61.0%). Regarding HIV-related health conditions and characteristics, 26.4% (n = 376) of the 1424 participants reported having chronic diseases, 8.1% (n = 116) received their diagnosis within 1 year, 39.3% (n = 560) reported their CD4+ T cell count level to be above 500/µL, 66.5% (n = 947) were infected through homosexual contact, 77.8% (n = 1108) reported mild sports activity, 81.0% (n = 1153) reported improvement of HIV/AIDS according to the doctors, 47.7% (n = 679) reported little or no anxiety, and 56.5% (n = 804) reported seldom or never depression ().

Table 1. Basic information among 1424 people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA).

Vaccine hesitancy

COVID-19 vaccination posed apprehension in 108 out of 1424 participants (7.6%). The hesitancy regarding COVID-19 vaccines varied according to sociodemographic and health condition characteristics. In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, vaccine hesitancy among PLWHA was linked with older age, lower educational level, higher income, presence of chronic disease conditions, lower CD4+ T cell counts, severe anxiety, severe depression, and high illness perception ( and Table S1).

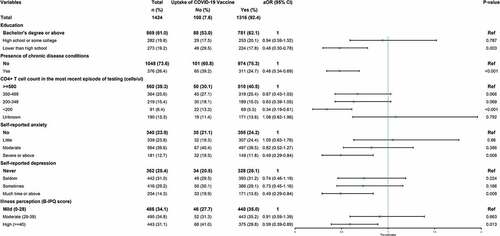

COVID-19 vaccination rate

A total of 1258 participants (88.3%) have already accepted at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccines. The COVID-19 vaccination rate also varied according to sociodemographic and health condition characteristics. In the multivariable logistic regression model, lower vaccination rates were associated with lower level of education, the presence of chronic disease, lower CD4+ T cell counts, severe anxiety, severe depression, and high illness perception ( and Table S2). Furthermore, when compared to the vaccinated group, the presence of chronic disease (aOR = 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.7) and lower than 200/µL CD4+ T cell counts (aOR = 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1–0.7) were linked with not hesitate but unvaccinated (Table S3). In the sensitivity analysis, the results were stable.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first cross-sectional study to simultaneously investigate COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and vaccination rate in the PLWHA population in China two years after the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. The overall vaccine hesitancy rate was 7.6%, and a higher hesitancy rate was associated with older age, presence of chronic disease conditions, a lower CD4+ T cell count, severe anxiety and depression, high illness perception, and so on. In our study, the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among PLWHA was 88.3%, and factors related to higher vaccination included a higher level of education, the absence of chronic disease, higher CD4+ T cell counts, and so on. With the ongoing emergence of COVID-19 variants, especially the recently discovered immune escape of omicron variants BA.4 and BA.5,Citation22 the relevance of vaccination in PLWHA population protection has been emphasized. PLWHA have been identified as one of the high-risk categories for COVID-19-related severe illness and death.Citation3 The findings of our study can be used to identify high-risk populations with poor vaccination intention and rate, allowing us to improve the vaccination coverage of the PLWHA population.

The degree of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in our study was 7.6%, which was lower than a prior study among PLWHA raised in China, and comparable to the results of non-HIV+ individuals in previous studies.Citation18,Citation23 A cross-sectional study conducted in China between July and August 2021 revealed that 27.5% of the PLWHA participants were hesitant to receive COVID-19 vaccines.Citation24 Another research, raised contemporaneously in China, found that 47.2% of the HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM) had higher vaccine hesitancy.Citation25 Nonetheless, in our study, PLWHA were less hesitant to receive COVID-19 vaccination than in other nations.Citation26–28 Overall, the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among PLWHA in our study was 88.3%, which was significantly higher than in prior studies. According to one research, only 8.7% of investigated HIV-infected MSM in China have been vaccinated against COVID-19 till February 2021.Citation25 Still, the vaccination rate is higher than in other nations and areas.Citation27,Citation29,Citation30 One possibility was that the high vaccination rate revealed in our study could be due to the government’s recent efforts to encourage immunization. The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Novel Coronavirus Vaccine Technical Guide (First Edition) provided a detailed answer to the topic of whether immunocompromised people should be vaccinated.Citation6 According to the safety features of past vaccines of the same type, the government advised that the PLWHA population receive inactivated vaccine and recombinant subunit vaccine. Another rationale was that the study setting (hospitals) and the study year (the year of 2022) might also be related with low vaccine hesitancy in this study. Furthermore, the dissemination of novel SARS-COV-2Citation11 and the impending recurrence of the original epidemic strainsCitation31–33 may also contribute to the large rise in COVID-19 vaccination among PLWHA. In our study, however, 11.7% of the PLWHA population is still unvaccinated. Recent studies have found that Omicron may evolve mutations to evade the humoral immunity elicited by BA.1 infection,Citation22 increasing the probability of COVID-19 infection in the PLWHA population. As a result, how to eradicate vaccine hesitancy among unvaccinated people remains a critical concern for PLWHA population.

Our study found that vaccine hesitancy was significantly influenced by old age. The reasons could be several. PLWHA are especially concerned about the potential harm of the COVID-19 vaccines to their immune system since they have reduced immune function.Citation5 According to the World Health Organization, sensationalist articles in the mainstream lay press may exacerbate uncertainty and doubt, perhaps leading to decreased COVID-19 vaccine coverage.Citation5 Existing research pointed to older people’s inability to grasp, analyze, and assess media content, such as the credibility of online news Citation34 and health information offered in the media.Citation35,Citation36 At the same time, senior persons, who may lack judgment on the authority of digital media, may find it difficult to gain access to reasonably approved institutions and organizations. What’s more, older people are more likely to suffer from chronic diseases, which raises concerns about the vaccination’s possible risk, thereby exacerbating their vaccine hesitancy. However, the World Health Organization states that elderly people are more prone to develop severe diseases if infected, thus they are among the top priority groups to be vaccinated.Citation37 As a result, we must ensure that the senior PLWHA population has easier access to vaccines and relevant health knowledge, that they have access to health care, and that they can assess the benefits and risks of immunization.

In our study, the PLWHA population’s CD4+ T cell count was a key factor influencing both vaccine hesitancy and uptake. A low CD4+ count indicated that the patient was less likely to comply with medical/HIV treatment/advice and hence was less likely to receive COVID-19 vaccine. The CD4+ T cell count is a well-known indication of the immunological and clinical state in HIV/AIDS.Citation38 We found that a lower CD4+ T cell count was associated with a reduced vaccination rate. According to an online site that provides access to the latest, federally approved HIV/AIDS medical practice guidelines, PLWH should receive the full series of COVID-19 vaccines regardless of CD4+ T count or viral load, because the possible benefits outweigh potential dangers.Citation39 Previous evidence also indicated that CD4+ T cell counts did not appear to alter immunogenicity,Citation10,Citation40 implying that PLWHA with a lower CD4+ T cell count level should be vaccinated, given their increased risk of SARS-COV-2 infection.

Anxiety and depression were found to have a substantial effect both on the rate of vaccine hesitancy and vaccination. There have been few studies on anxiety, depression, and vaccine hesitancy in the PLWHA population.Citation25 However, studies have found that anxiety suppressors are more prone than the overall population to be vaccine hesitant. A prior study conducted among the general population in China found that participants with moderate or severe levels of generalized anxiety were more likely to be unwilling to be vaccinated.Citation31 Another study found that immunization was inversely associated with fears of unpleasant reactions, a detrimental influence on HIV/AIDS progression, or antiretroviral medication.Citation15

Our study showed that the presence of chronic disease was associated with not being hesitant but remaining unvaccinated. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, investigations and trials on COVID-19 vaccines have been actively conducted across the country,Citation32,Citation33 and many studies have reported the effectiveness and safety of vaccination for patients with chronic diseases in the general population,Citation41 but there is relatively insufficient evidence on the safety and efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine among PLWHA with chronic diseases. Concerns about vaccine safety among PLWHA with chronic disease may be related with delayed vaccination. Our findings suggested that in the future, RCT and real-world research on the effectiveness and safety of COVID-19 vaccines for PLWHA with chronic diseases should be strengthened, which could help to raise the PLWHA population’s vaccination rate on the basis of safety.

However, there are some limitations in this study. First, selection bias could not be avoided as convenience sampling was used and participants were only caught in hospital settings, despite the fact that the overall number of PLWHA in China was estimated to be 1.053 million.Citation42 Also, subjectively self-administered questionnaire may lead to recall bias regarding clinical data, which was also ineluctable in consideration of thoroughly confirming the anonymity of the study. Second, we did not thoroughly study the brand of PLWHA vaccine and vaccination doses, which may have overlooked the increase in vaccination hesitancy induced by the vaccine’s influence on patients. Third, we used a proxy question “Do you think people living with HIV/AIDS should be vaccinated against COVID-19?” to investigate the vaccine hesitancy, which can vary between individuals and groups. Fourth, we did not gather risk perception about COVID-19 disease and vaccine, as well as other potential hesitation factors (such as CD4/CD8 ratio, viral load, and cognition function). Fifth, we did not employ well-established standard questionnaires to assess psychological aspects. The results we have so far are far from comprehensive. In the course of future studies, especially in evaluating vaccine hesitancy, we will refine our surveys on the severity and risk of specific diseases and the perception of vaccine benefits and side effects in specific patient populations to provide more accurate analyses.

Conclusions

To summarize, approximately one-tenth of PLWHA are still hesitant to be vaccinated, and more than eight in ten have received at least one dose of the vaccine. Higher COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was related to older age, a lower educational level, higher income, presence of chronic disease conditions, lower CD4+ T cell counts, severe anxiety and severe depression, and a high illness perception. Factors related to a lower vaccination rate included a lower level of education, the presence of chronic disease, lower CD4+ T cell counts, severe anxiety, severe depression, and high illness perception. When compared to vaccinated participants, the presence of chronic disease was related to not being hesitate but unvaccinated. Our findings highlighted that tailored interventions (e.g., targeted education programs) based on these associated factors were required to reduce concerns for PLWHA in promoting their COVID-19 vaccination rate, particularly for PLWHA with lower education levels, lower CD4+ T cell counts, and severe anxiety and depression. Furthermore, research on the effectiveness and safety of COVID-19 vaccines for PLWHA with chronic diseases should be strengthened to promote vaccination behavior among the PLWHA population who have vaccination willingness in the future.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Jue Liu; Data curation, Xuan Lv, Chaobo Zhao, Su Song, Hai Long, and Weidong Liu; Formal analysis, Xuan Lv; Methodology, Xuan Lv, Chaobo Zhao and Jue Liu; Supervision, Jue Liu; Writing – original draft, Xuan Lv and Chaobo Zhao; Writing – review & editing, Xuan Lv, Chaobo Zhao, Min Du, Huihuang Huang, Bing Song, Su Song, Hai Long, Weidong Liu, Min Liu and Jue Liu.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University (IRB00001052-22008) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent statement

All participants signed paper informed consent forms prior to participating in the survey.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (185 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants in this study and the staff who contributed during the data collection process. We are also thankful to the Fifth Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Guiyang Public Health Clinical Center, and the Fourth People’s Hospital of Datong for facilitating the investigation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data set used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2151798

Additional information

Funding

References

- Yang X, Sun J, Patel RC, Zhang J, Guo S, Zheng Q, Olex AL, Olatosi B, Weissman SB, Islam JY, et al. Associations between HIV infection and clinical spectrum of COVID-19: a population level analysis based on US National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) data. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(11):e690–9. doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00239-3.

- Garbuglia AR, Minosse C, Del Porto P. mRNA- and adenovirus-based vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 in HIV-Positive people. Viruses. 2022;14(4):748. doi:10.3390/v14040748.

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): COVID-19 vaccines and people living with HIV. [ accessed 2021 Jul 14]. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-covid-19-vaccines-and-people-living-with-hiv.

- Trogen B, Oshinsky D, Caplan A. Adverse consequences of rushing a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: implications for public trust. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2460–61. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.8917.

- Harrison N, Poeppl W, Herkner H, Tillhof KD, Grabmeier-Pfistershammer K, Rieger A, Forstner C, Burgmann H, Lagler H. Predictors for and coverage of influenza vaccination among HIV-positive patients: a cross-sectional survey. HIV Med. 2017;18(7):500–06. doi:10.1111/hiv.12483.

- Technical guideline for the inoculation of COVID-19 vaccines. [ accessed 2021 Apr 1]. http://en.nhc.gov.cn/2021-04/01/c_83365.htm.

- Trovato M, Sartorius R, D’Apice L, Manco R, De Berardinis P. Viral emerging diseases: challenges in developing vaccination strategies. Front Immunol. 2020;11:2130. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.02130.

- Hoffmann C, Casado JL, Härter G, Vizcarra P, Moreno A, Cattaneo D, Meraviglia P, Spinner CD, Schabaz F, Grunwald S, et al. Immune deficiency is a risk factor for severe COVID-19 in people living with HIV. HIV Med. 2021;22(5):372–78. doi:10.1111/hiv.13037.

- Safety of COVID-19 vaccines. [ accessed 2021 Mar 31]. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/safety-of-covid-19-vaccines.

- Levy I, Wieder-Finesod A, Litchevsky V, Biber A, Indenbaum V, Olmer L, Huppert A, Mor O, Goldstein M, Levin EG, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in people living with HIV-1. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(12):1851–55. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2021.07.031.

- Frater J, Ewer KJ, Ogbe A, Pace M, Adele S, Adland E, Alagaratnam J, Aley PK, Ali M, Ansari MA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdox1 nCov-19 (AZD1222) vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in HIV infection: a single-arm substudy of a phase 2/3 clinical trial. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(8):E474–85. doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00103-X.

- Tuan JJ, Zapata H, Critch‐gilfillan T, Ryall L, Turcotte B, Mutic S, Andrews L, Roh ME, Friedland G, Barakat L, et al. Qualitative assessment of anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein immunogenicity (QUASI) after COVID-19 vaccination in older people living with HIV. HIV Med. 2022;23(2):178–85. doi:10.1111/hiv.13188.

- Vallee A, Fourn E, Majerholc C, Touche P, Zucman D. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among French people living with HIV. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(4):302. doi:10.3390/vaccines9040302.

- Zintel S, Flock C, Arbogast AL, Forster A, von Wagner C, Sieverding M. Gender differences in the intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2022;1–25. doi:10.1007/s10389-021-01677-w.

- Zhao HP, Wang H, Li H, Zheng W, Yuan T, Feng A, Luo D, Hu Y, Sun Y, Lin Y-F, et al. Uptake and adverse reactions of COVID-19 vaccination among people living with HIV in China: a case–control study. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(12):4964–70. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1991183.

- Transcript of the Press Conference of the Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of The State Council on November 30, 2021. [ accessed 2021 Nov 30]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/gwylflkjz174/index.htm.

- Tao L, Wang R, Han N, Liu J, Yuan C, Deng L, Han C, Sun F, Liu M, Liu J. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women in China: a multi-center cross-sectional study based on health belief model. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(8):2378–88. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1892432.

- Qin C, Wang R, Tao L, Liu M, Liu J. Acceptance of a third dose of COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors in China based on health belief model: a national cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(1):89. doi:10.3390/vaccines10010089.

- Du M, Tao L, Liu J. The association between risk perception and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for children among reproductive women in China: an online survey. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:741298. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.741298.

- Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(6):631–37. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020.

- Teunissen JS, van der Oest MJW, van Groeninghen DE, Feitz R, Hovius SER, Van der Heijden EPA. The impact of psychosocial variables on initial presentation and surgical outcome for ulnar-sided wrist pathology: a cohort study with 1-year follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):109. doi:10.1186/s12891-022-05045-x.

- Cao Y, Yisimayi A, Jian F, Song W, Xiao T, Wang L, Du S, Wang J, Li Q, Chen X, et al. BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 escape antibodies elicited by Omicron infection. Nature. 2022;608(7923):593–602. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04980-y.

- Tao L, Wang R, Liu J. Comparison of vaccine acceptance between COVID-19 and seasonal influenza among women in China: a national online survey based on health belief model. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:679520. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.679520.

- Liu Y, Han J, Li X, Chen D, Zhao X, Qiu Y, Zhang L, Xiao J, Li B, Zhao H. COVID-19 vaccination in people living with HIV (PLWH) in China: a cross sectional study of vaccine hesitancy, safety, and immunogenicity. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(12):1458. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121458.

- Zheng W, Sun Y, Li H, Zhao H, Zhan Y, Gao Y, Hu Y, Li P, Lin Y-F, Chen H. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and hesitancy among HIV-infected men who have sex with men in mainland China: a cross-sectional survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(12):4971–81. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1996152.

- Nusair MB, Arabyat R, Khasawneh R, Al-Azzam S, Nusir AT, Alhayek MY. Assessment of the relationship between COVID-19 risk perception and vaccine acceptance: a cross-sectional study in Jordan. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(1):2017734. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2017734.

- Jaiswal J, Krause KD, Martino RJ, D’Avanzo PA, Griffin M, Stults CB, Karr AG, Halkitis PN. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination hesitancy and behaviors in a national sample of people living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2022;36(1):34–44. doi:10.1089/apc.2021.0144.

- Ekstrand ML, Heylen E, Gandhi M, Steward WT, Pereira M, Srinivasan K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among PLWH in South India: implications for vaccination campaigns. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;88(5):421–25. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000002803.

- Menza TW, Capizzi J, Zlot AI, Barber M, Bush L. COVID-19 vaccine uptake among people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(7):2224–28. doi:10.1007/s10461-021-03570-9.

- Prestage G, Storer D, Jin F, Haire B, Maher L, Philpot S, Bavinton B, Saxton P, Murphy D, Holt M. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and its impacts in a cohort of gay and bisexual men in Australia. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(8):2692–702. doi:10.1007/s10461-022-03611-x.

- Sekizawa Y, Hashimoto S, Denda K, Ochi S, So M. Association between COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and generalized trust, depression, generalized anxiety, and fear of COVID-19. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):126. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-12479-w.

- Li Q, Lu HZ. Latest updates on COVID-19 vaccines. Biosci Trends. 2020;14(6):463–66. doi:10.5582/bst.2020.03445.

- Shereen MA, Bashir N, Khan MA, Kazmi A, Khan S, Zhen L, Wu J, et al. Covid-19 management: traditional Chinese medicine Vs. Western medicinal antiviral drugs, a review and meta-analysis. Fresenius Environ Bull. 2021;30(5):5537–49.

- Guess A, Nagler J, Tucker J. Less than you think: prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Sci Adv. 2019;5(1):eaau4586. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aau4586.

- Eronen J, Paakkari L, Portegijs E, Saajanaho M, Rantanen T. Assessment of health literacy among older Finns. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(4):549–56. doi:10.1007/s40520-018-1104-9.

- Rasi P, Vuojärvi H, Rivinen S. Promoting media literacy among older people: a systematic review. Adult Educ Q. 2020;71:37–54. doi:10.1177/0741713620923755.

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Vaccines. [ accessed 2022 Mar 16]. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-vaccines.

- Ford N, Meintjes G, Vitoria M, Greene G, Chiller T. The evolving role of CD4 cell counts in HIV care. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12(2):123–28. doi:10.1097/COH.0000000000000348.

- Guidance for COVID-19 and People with HIV. [ accessed 2022 Feb 22]. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/guidance-covid-19-and-people-hiv/guidance-covid-19-and-people-hiv?view=full.

- Milano E, Ricciardi A, Casciaro R, Pallara E, De Vita E, Bavaro DF, Larocca AMV, Stefanizzi P, Tafuri S, Saracino A. Immunogenicity and safety of the BNT162b2 COVID-19 mRNA vaccine in PLWH: a monocentric study in Bari, Italy. J Med Virol. 2022;94(5):2230–36. doi:10.1002/jmv.27629.

- Feikin DR, Higdon MM, Abu-Raddad LJ, Andrews N, Araos R, Goldberg Y, Groome MJ, Huppert A, O’Brien KL, Smith PG. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet. 2022;399(10328):924–44. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00152-0.

- Na H. Research progress in the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in China. China CDC Wkly. 2021;3(48):1022–30. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2021.249.