ABSTRACT

Before COVID-19, influenza vaccines were the most widely recommended vaccine during pregnancy worldwide. In response to immunization during pregnancy, maternal antibodies offer protection against potentially life-threatening disease in both pregnant people and their infants up to six months of age. Despite this, influenza vaccine hesitancy is common, with few countries reporting immunization rates in pregnant people above 50%. In this review, we highlight individual, institutional, and social factors associated with influenza vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy. In addition, we present an overview of the evidence evaluating interventions to address influenza vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy. While some studies have indicated promising results, no single intervention has consistently effectively increased influenza vaccine uptake during pregnancy. Using a social-ecological model of health framework, future strategies addressing multiple levels of vaccine hesitancy will be needed to realize the potential health benefits of prenatal immunization programs.

Plain Language Summary

Pregnant people are a high priority group for influenza vaccination annually. Although vaccination can protect both mother and infant, vaccination rates are suboptimal during pregnancy. Previous research has suggested reasons for suboptimal vaccination rates, including concerns about the safety of vaccination during pregnancy and limited access to, and awareness of, influenza vaccines during pregnancy. Studies that have attempted to increase influenza vaccination rates during pregnancy have mostly shown no effect – with some exceptions. Public health professionals need to reevaluate strategies for improving vaccination rates during pregnancy.

Introduction

Influenza illness causes a significant global burden of disease, contributing to over five million hospitalizations and up to 645,000 deaths annually.Citation1,Citation2 Population groups where the risk of hospitalization is greatest include older adults, individuals with predisposing medical conditions, certain racial and ethnic minority groups, pregnant people, and infants <6 months old. Pregnancy is a risk factor for severe influenza infection, with pregnant people at a seven-fold increase in the risk of influenza-associated hospital admissions compared to the non-pregnant population.Citation3 This increased susceptibility to severe illness is particularly observable during influenza pandemics.Citation4,Citation5 For example, although pregnant people account for just 1% of the U.S. population, they accounted for 5% of deaths in the U.S. during the 2009 influenza A/H1N1 pandemic.Citation4 Influenza infection during pregnancy impacts both maternal and fetal health.Citation6 In addition to an increased risk of maternal health complications, a recent prospective cohort study of three middle-income countries found that prenatal influenza infection was linked with a 10-fold increase in the risk of stillbirth, and was associated with lower birthweight compared to no maternal infection.Citation7

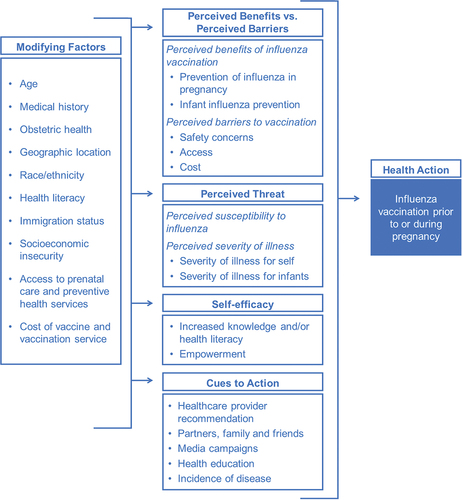

Infants <6 months old are also at higher risk of severe influenza compared to other population groups, and the burden of influenza disproportionately affects infants <6 months old compared to older children. Between 4 and 15% of children under the age of five years require medical care for laboratory-confirmed influenza during the influenza season. Hospitalization rates range from 0.4 to 1.0 per 1,000 children under the age of five years;Citation8,Citation9 Rates of influenza hospitalization are more than three-fold higher among infants <6 months old compared to infants 2–4 years old,Citation8 and pediatric influenza-associated deaths are highest among infants <6 months old.Citation10 Globally, 16% of influenza-associated deaths occur in children <5 years of age, predominantly among infants <6 months old.Citation2 Because six months of age is the earliest that effective influenza vaccines can be administered, primary immunization is not possible for infants <6 months old, leaving them susceptible to potentially life-threatening influenza infections ().

Figure 1. Direct and indirect health impacts of influenza on infants <6 months of age.

Seasonal influenza immunization offers the best method of protection against severe disease for pregnant people and infants <6 months old. Maternal antibodies produced in response to vaccination have been shown to protect the mother from severe infection.Citation11 Because these antibodies also cross the placenta, they additionally offer passive protection for infants until six months of age.Citation12 Despite the benefits of influenza immunization for pregnant people and infants <6 months old, hesitancy toward influenza vaccination during pregnancy has been a long-standing, global issue for the successful implementation of influenza vaccination programs.Citation13 As defined by the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy, vaccine hesitancy is the delay in acceptance, or refusal of vaccination, despite the availability of vaccination services.Citation14 Despite the availability of influenza vaccines in more than 75% of high-income countries that have recommendations promoting prenatal immunization,Citation15 influenza vaccination rates during pregnancy across multiple high-income countries have historically been suboptimal.Citation16 In the US, only 61% of pregnant people received an influenza vaccine during the 2019–20 influenza season.Citation17 Similarly suboptimal immunization rates are reported in other high-income countries, including the UK, Canada, and Australia.Citation18–20 Limited data are available to document influenza vaccination rates among pregnant people in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). However, immunization rates in LMICs are anticipated to be low, given influenza vaccines are not included in Global Vaccine Alliance (GAVI) support and 4% of GAVI-eligible and only 26% of GAVI-ineligible LMICs have policies recommending influenza vaccination during pregnancy.Citation15 Closing the maternal influenza vaccination gap is a global public health priority.

This review highlights the available evidence on the individual and systems-level factors associated with influenza vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy – as well as evidence to support future interventions to improve vaccination rates and improve health outcomes for mothers and infants <6 months old.

Search methodology

We searched online databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Embase, from inception to 10 September 2022 for articles relevant to two themes: 1) influenza vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy and 2) strategies for increasing vaccine acceptance during pregnancy. Search terms to identify factors associated with influenza vaccine hesitancy included keywords related to “influenza,” “vaccine uptake,” “vaccine predictors,” “vaccine hesitancy,” and “pregnancy.” Search terms to identify interventions to increase influenza vaccine acceptance included keywords related to “influenza vaccine,” “intervention,” “strategy,” and “pregnancy.” We additionally searched clinicaltrials.gov to identify ongoing randomized controlled trials that aim to increase vaccine acceptance during pregnancy. We provide a narrative synthesis of articles and ongoing studies identified through this search.

Factors associated with prenatal vaccine hesitancy

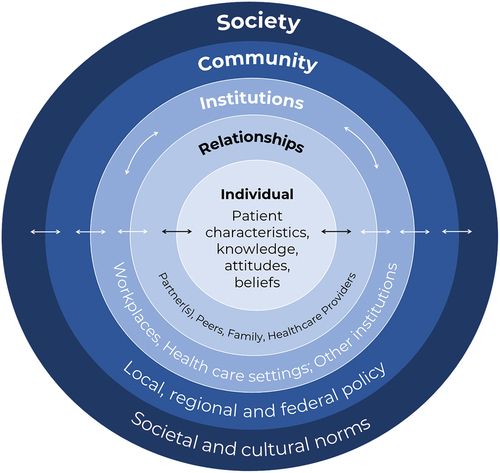

The factors associated with influenza vaccine acceptance and hesitancy during pregnancy have been extensively evaluated, particularly following the 2009 influenza A/H1N1 pandemic. A systematic review identified key categories of factors associated with prenatal vaccine hesitancy, including vaccine access and convenience, individual and cultural values, health literacy, social influences, emotions regarding vaccination, and perceptions of vaccine risk and benefit and personal vaccination history.Citation21 Guided by the Health Belief Model, these factors can be grouped into modifying factors, individual beliefs, and cues to action ().Citation22

Modifying factors

Much of the existing literature has focused on individual-level factors that modify the probability of influenza vaccination during pregnancy.Citation13,Citation23,Citation24 Studies of sociodemographic factors associated with vaccine hesitancy have identified younger age, higher parity, and being unmarried/partnered and/or unemployed. Additionally, delayed and inadequate prenatal care as well as lack of preexisting medical conditions are positively associated with influenza vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy.Citation23 In 2020, although 61% of pregnant people in the U.S. received an influenza vaccine, notable social and economic disparities exist. In 2020, immunization rates were lowest among pregnant people who were: Black (53%), ages 18–24 (55%), unmarried (49%), with a high-school education or less (46%), and those who were unemployed (51%), living below poverty or relying on public health insurance (48%), and living in a rural area of the U.S. (57%).Citation17

A history of influenza vaccination is one of the strongest predictors of influenza vaccine acceptance among pregnant and non-pregnant adults.Citation23,Citation25 Among pregnant people, the odds of receiving an influenza vaccine are nearly four times higher for those who have previously received an influenza vaccine.Citation21 However, this behavior may not apply to immunization history outside of pregnancy. Some studies have shown that acceptance of seasonal influenza vaccine in a prior pregnancy is not associated with receipt of seasonal influenza vaccines in a future pregnancy.Citation21 While much of the evidence supporting these factors have been documented in high-income countries, a recent systematic review of 11 studies reported similar factors associated with influenza vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy in low- and middle-income countries.Citation26

Because influenza vaccines are administered seasonally, vaccination is most likely to occur during pregnancies that coincide with influenza vaccine availability, typically offered several months before the start of the influenza season. Several studies have documented the influence of gestational age and calendar time on the likelihood of receiving seasonal influenza vaccination during pregnancy.Citation27–29 Furthermore, vaccination rates tend to be highest during the second and third trimesters, with multiple factors contributing to differences in vaccine uptake by gestational age. The observed hesitancy to vaccinate early in pregnancy has been linked with patient and provider concerns about safety for vaccination for early fetal development.Citation30,Citation31 In addition, several national policies, predominantly in parts of Europe, have specifically excluded the first trimester in their recommendation of influenza vaccination during pregnancy.Citation32 As a result, vaccination rates are lowest among those in the first trimester of pregnancy at the start of influenza vaccine campaigns.Citation27

Health literacy is another important individual factor that has been linked with influenza vaccination hesitancy during pregnancy. The odds of influenza vaccination are more than five times higher among pregnant people who have general information about the vaccine and three times higher among pregnant people who are aware of national vaccine recommendations.Citation21 Surveys of pregnant people from around the world have consistently documented low awareness of influenza vaccine recommendations during pregnancy,Citation29–35 with one survey in China indicating awareness of vaccine recommendations was as low as 15% among pregnant patients.Citation36

Individual beliefs associated with maternal influenza vaccine hesitancy

Individual beliefs are influential in the likelihood of influenza vaccination, and some have previously suggested that individual beliefs are more influential than sociodemographic factors.Citation37 Numerous studies have documented concerns about the safety of influenza vaccination during pregnancy as one of the most influential factors driving vaccine hesitancy. Concerns about the safety of vaccines administered during pregnancy have been commonly cited by both pregnant patients and healthcare providers.Citation13,Citation24,Citation38 The odds of influenza vaccination are lower for pregnant people who believe influenza vaccine is unsafe or causes birth defects or miscarriage.Citation21 Concerns about side effects of influenza vaccination in general are associated with a 2–3 fold lower odds of influenza vaccination.Citation21

Perceived susceptibility to influenza, perceived severity of disease, and perceived benefits of influenza vaccination are also influential factors.Citation38 Vaccination is more common when pregnant people believe the influenza vaccine is effective, has benefits for the mother, and has benefits for their infant.Citation21 Pregnant people who believe they are susceptible to seasonal influenza have nearly two-fold greater odds of influenza vaccination compared to those who do not feel they were susceptible to influenza infection.Citation21 Further, pregnant people who believe that seasonal influenza can be harmful to their pregnancy or their unborn infant are nearly four times more likely to receive seasonal influenza vaccine.Citation21

Cues to action

The strongest predictor of influenza vaccination during pregnancy is receipt of a recommendation from a healthcare provider.Citation21 A meta-analysis of 49 studies found that the odds of influenza vaccination was 12 times higher among those who received a healthcare provider recommendation compared to those who received no recommendation.Citation21 Qualitative research has indicated that the offer of vaccination by a healthcare provider during a prenatal care visit was often a key factor in the final decision to vaccinate.Citation21 Recommendation by healthcare providers serves multiple roles; they are a cue to action, can improve health literacy, and be used to address concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy.

Despite the strong link between a healthcare provider recommendation and influenza vaccine acceptance during pregnancy, not all providers recommend influenza vaccination to pregnant patients, and the likelihood of receiving a recommendation is dependent on calendar time, medical risk factors, sociodemographic factors, and the type of prenatal care provider.Citation29,Citation39 For example, a recent study in Germany showed that between 2015 and 2018, just 20% of the pregnant individuals received a vaccine recommendation during their pregnancy. Just as individual-level factors have been linked with vaccine hesitancy, similar individual-level factors have been associated with receipt of a vaccine recommendation from a healthcare provider. Having a high-risk pregnancy, not being foreign-born, and conception in spring are each associated with a higher likelihood of receiving a healthcare provider recommendation for influenza vaccination.Citation29,Citation39 Black and uninsured pregnant people are also less likely to report receipt of an influenza vaccine recommendation by a healthcare provider.Citation20,Citation40

Although obstetric policymaking bodies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommend influenza vaccination during pregnancy,Citation41 some providers express hesitation in recommending influenza vaccination to pregnant patients or report challenges in administering vaccines. Historical surveys conducted between 2003 and 2006 have shown that 5–6% of U.S. obstetricians feel vaccines should not be given during pregnancy, and 50–68% do not feel influenza vaccine should be administered during the first trimester.Citation42,Citation43 While support for influenza vaccination has increased among obstetricians, the proportion of prenatal care providers outside the U.S. who recommend or administer influenza vaccines to pregnant patients can be much lower (<70%).Citation44–46

Several institutional barriers may influence the likelihood of a healthcare provider recommendation and/or offer of vaccination. Immunization services increase demands on facilities and staffing, including vaccine purchasing, cold chain storage, and reimbursement. Challenges to vaccine ordering, supply maintenance, and storage are relatively newer challenges to obstetricians,Citation47,Citation48 and these challenges have been previously linked with lower immunization rates. For example, immunization rates are lower in clinical settings that do not include adequate staffing or workload allocation to support immunization service provision.Citation38,Citation49

Prenatal care providers who are not obstetricians also have an influential role in reducing influenza vaccine hesitancy among pregnant patients. Although more than 60% of pregnant people say they would have been vaccinated if a midwife or primary care provider recommended the vaccine, several studies have shown that midwives and primary care providers hesitate to recommend vaccines to pregnant patients.Citation50,Citation51 Pregnant people who receive most of their prenatal care from a primary care provider or midwife are less likely to be recommended influenza vaccine compared to those receiving prenatal care from an obstetrician.Citation39 Although midwives express interest in advising pregnant patients on influenza vaccination, previous surveys in multiple countries have documented barriers, including logistical, interprofessional, and educational barriers.Citation52–55 Different views on which healthcare provider is responsible for offering influenza vaccination for pregnant patients have been cited by primary care providers, obstetricians and midwives.Citation50,Citation51 Regardless, lack of a healthcare provider recommendation presents a missed opportunity for vaccination.

Other potential sources of cues to action include spouses/partners, family members, and pregnant peers. However, these social cues to action have been less commonly evaluated for influenza vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy. While one small qualitative study indicated that family and friends have little influence on decision to vaccinate,Citation56 having family and friends vaccinated against COVID-19 has been identified as a protective factor against COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy. The potential influence of partners, peers, family, and society on influenza vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy should be further evaluated.

Socioeconomic & regional disparities in maternal influenza immunization

Several of the individual and provider-level factors discussed impact select population groups more than others. Disparities in influenza vaccination rates are influenced by various social determinants of health (SDoH), most specifically neighborhood and built environment, economic instability, healthcare access and quality, language and literacy, and race/ethnicity and discrimination.Citation57 Studies have consistently shown that individuals with greater social and economic vulnerability who have publicly funded or no insurance coverage are less likely to receive influenza vaccination during pregnancy.Citation58–61 This may be particularly problematic in rural settings, where pregnant people rely more heavily on publicly funded prenatal care and primary care providers and more frequently experience healthcare professional shortages.Citation61–63 As a result, pregnant people in rural areas may experience fewer opportunities to receive vaccines, may not be recommended or offered influenza vaccine as frequently as urban-residing pregnant people, and may be less aware of vaccine recommendations – all factors positively associated with influenza vaccination during pregnancy.Citation39,Citation61 These barriers can be seen in lower immunization rates observed in rural areas. For example, a recent analysis of U.S. data indicated that the absolute prevalence of influenza vaccination was 4% lower among rural-residing pregnant people compared to urban-residing pregnant people.Citation64

One of the greatest disparities in influenza immunization rates reported has been by race. Black pregnant people in the U.S. consistently have the lowest rate of influenza immunization during pregnancy and are less likely to receive recommendations from healthcare providers.Citation40,Citation65,Citation66 Even after receiving a provider recommendation, influenza immunization rates among Black pregnant people are 9% lower compared to white pregnant people.Citation17 A survey of pregnant people in two U.S. states (Georgia and Colorado) showed that Black and Latina/x pregnant people are less confident in vaccine safety and efficacy and have a lower perceived risk of disease compared to white pregnant people.Citation67 These observations may be influenced by medical mistrust, an issue highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic.Citation68,Citation69

In addition to disparities within countries and regions, significant global disparities exist regarding access to influenza vaccines during pregnancy. Despite global recommendations by the WHO,Citation70 as of 2014, only 4% of low and lower-middle-income countries who were GAVI-eligible countries, 26% of countries from low and lower-middle-income countries who were not GAVI-eligible and 50% of upper-middle-income countries had a policy recommending influenza vaccination during pregnancy.Citation15 Among WHO Member States, 6% of Member States in the Africa region, 18% of Member States in the South-East Asian region, and 38% of Member States in the East Mediterranean region have influenza vaccine policies targeting pregnant people.Citation15 Low rates of vaccine recommendations are likely to be driven by limited data on influenza burden, healthcare infrastructure and complex vaccine supply issues in low- and middle-income countries.Citation71

Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal influenza vaccine hesitancy

Multiple studies have documented the disruption to childhood immunization programs resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic,Citation72–77 indicating that in 2020 alone, coverage of recommended childhood immunizations has declined globally by 2.7%.Citation78 However, fewer studies have documented the impact on adult immunization services. One UK study of 1,404 recently pregnant people found that 40% of respondents had a pregnancy vaccination appointment canceled by their provider, 21% reported difficulty accessing pregnancy vaccinations, and 45% experienced fear related to attending pregnancy vaccination appointments during the pandemic.Citation79 A small international survey of 48 clinicians found that more than 50% of clinicians reported challenges delivering recommended prenatal vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic, including issues with patient access to immunization services due to social distancing and lockdown measures and fear of infection, clinical staff shortages, and vaccine supply issues.Citation80 Post-pandemic declines in influenza immunization have been documented in the Vaccine Safety Datalink data, with 66% of pregnant people vaccinated in the 2019–20 season, 61% in the 2020–21 season, and 52% in the 2021–22 influenza season. Despite these rates, the COVID-19 pandemic may positively influence influenza vaccine acceptance in the future. Additional surveys have shown that pregnant people report greater trust in healthcare providers in providing vaccine information after the COVID-19 pandemic.Citation81 This may be an indication that the COVID-19 pandemic could potentially improve influenza immunization rates among pregnant people, but more research is needed.

Promoting influenza immunization during pregnancy

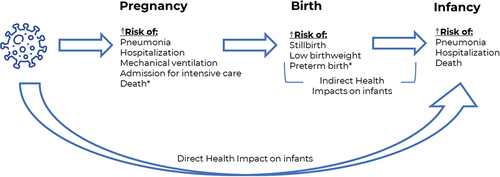

Influential factors driving influenza vaccine behavior during pregnancy can be addressed at multiple levels, from the individual to society. Drawing from Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory and the Ecological Model of Health Behaviors, the Social-Ecological Model of Health Promotion can serve as a useful framework for implementing multi-level interventions to increase influenza vaccine uptake among pregnant people. The socio-ecological model of health identifies myriad factors that influence health at five intersecting levels: (1) individual, (2) relationship/interpersonal, (3) institutional, (4) community, and (5) society ().Citation82 Examining each level of the Social-Ecological Model can help to develop targeted interventions to address vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy.

The individual-level constitutes a pregnant persons’ health status and sociodemographic factors, as well as their knowledge, skills, and attitudes regarding influenza vaccines. Interventions at this level tend to focus on education and skill-building, possibly utilizing motivational interviewing. The relationship or interpersonal-level considers the influence of formal and informal social support networks that have direct contact with the pregnant person, including spouses/partners, family, friends, and peer groups. For pregnant people, interventions at this level may target the health literacy and influence of familial and social networks and leverage the support of pregnant peers.

Moving on to systems-level factors, the institutional-level includes rules and social interactions that occur within institutions, such as schools, workplaces, and healthcare systems. Interventions at this level may address patient-provider communication, provider and staff education, and healthcare information technology (e.g., provider alerts or mHealth interventions). The community-level reflects the larger social system in which pregnant people and their relationships occur. Interventions at this level address local, regional, and federal policy, and may include health plan incentives, access to low-cost or free vaccines, and health policies that promote and support vaccination during pregnancy. Finally, the society-level reflects the macrosystem and cultural context in which pregnant people and their contacts reside, including cultural and social norms. These can directly or indirectly influence individual behavior through policies and programs promoting immunization. Interventions at this level may address social norms by developing tailored social marketing and health communication campaigns.

Data on strategies to increase influenza vaccination during pregnancy

To date, there is limited evidence outlining a consistently effective intervention to address vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy. Previous investigators have classed interventions into three groups: staff education and training, information, and education for patients, and health systems improvements,Citation83 and these interventions have predominantly targeted individual and institutional-level factors and patient-provider communication (). These interventions have offered mixed and often disappointing results, and despite the benefits of multi-component strategies, it is impossible to disentangle the effects of specific constituent strategies.Citation40,Citation83,Citation109

Table 1. Summary of strategies for increasing influenza vaccine acceptance during pregnancyCitation40,Citation83.

Individual and institutional-level factors which have shown some positive effects on influenza vaccination rates include patient and provider reminders (i.e., “nudges”), midwifery-led immunization services, and patient and provider education.Citation83–93 Similar strategies have been evaluated for pertussis vaccine promotion during pregnancy and have been found to be effective.Citation109 For example, a randomized controlled trial of 321 pregnant people showed that patient education was effective in doubling influenza vaccination rates during pregnancy.Citation84

More recently, there has been work to deploy motivational interviewing interventions in clinical settings to promote prenatal immunization.Citation94 Motivational Interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based practice that originated from alcohol and substance-abuse counselingCitation95 and is increasingly used in a range of health-related behavioral interventions.Citation96,Citation97 MI is a technique that aims to support decision-making by applying a person-centered collaborative approach to behavior change using open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries (i.e., OARS) to promote self-efficacy and motivation to adopt positive health behaviors.Citation54,Citation94,Citation98,Citation99 Although multiple experimental and quasi-experimental studies have shown MI can effectively be used to address parental vaccine hesitancy,Citation100–102 the effects of MI have not yet been well described in pregnant people. Several ongoing trials are currently evaluating the use of motivational interviewing to increase vaccine acceptance during pregnancy. For example, an ongoing pragmatic controlled trial in Colorado (U.S.) will train prenatal care providers to use motivational interviewing with pregnant patients.Citation98

Results have not consistently supported a strong effect of these individual and provider-level strategies. Despite some promise,Citation84,Citation103 results from clinical trials have not consistently identified positive improvement in vaccination rates associated with patient and provider educationCitation85–87–Citation104 or with immunization reminders or nudges,Citation105,Citation106 with some concluding that improving patient education and awareness is likely insufficient on its own to address vaccine hesitancy.Citation13,Citation40 A recent systematic review indicated that although awareness of recommended vaccines during pregnancy is associated with vaccine acceptance, awareness alone is rarely sufficient to drive vaccine behavior.Citation21

Fewer studies have targeted the effects that personal relationships can have on vaccine decision-making. One recent chart review in Florida (U.S.) compared vaccination rates among patients who received prenatal care in a CenteringPregnancy approach (i.e., evidence-based group prenatal care) to those who received traditional individualized prenatal care.Citation107 The investigators observed a 24% absolute increase in influenza vaccine uptake and 12% absolute increase in pertussis vaccine uptake among CenteringPregnancy patients compared to traditional care patients.Citation107 While these results are promising and may allude to the power of peer influence on medical decision-making, this study was observational and single center, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

Although more recently investigators have initiated social media campaigns to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy,Citation108 to our knowledge, the effects of mass and social media campaigns on uptake of influenza vaccines among pregnant people have not yet been evaluated. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the One Vax Two Lives social media campaign was created to increase public access to evidence on COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy.Citation108 Although the impact of this campaign on COVID-19 vaccination rates during pregnancy have not yet been reported, similar campaigns could be evaluated in the context of other recommended vaccines, including influenza vaccine.

As evidenced by existing data, it is unlikely that interventions solely focusing on individual-level factors or awareness alone will offer significant success. Considering this, strategies for addressing influenza vaccine hesitancy among pregnant people require reevaluation. Future studies should evaluate the effect of interventions targeting multiple levels of factors influencing influenza vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy – from individual to societal.

When considering intervention strategies, it is important to note the interplay between each level. For example, peer interventions (e.g., group prenatal care or new parent classes) leverage interpersonal relationships, but also require institutional buy-in (e.g., provider recruitment and education) and community-level supports (e.g., insurance coverage of group care) to be viable. As another example, health literacy interventions using motivational interviewing may require addressing both the institutional (e.g., staff and provider training) and individual-levels (e.g., assessing potential change in knowledge, attitudes, and skills). Looking forward, multi-component interventions which target the overlapping levels of the social ecological environment may offer more success than individual-level interventions alone in reducing influenza vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy, thereby improving health outcomes among pregnant people and infants <6 months old.

Conclusions

Pr7enatal influenza immunization has the potential to protect against severe illness in pregnant people and infants <6 months old. Despite its promise, vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy has historically hindered the health impacts of prenatal immunization, and few studies have identified interventions that can consistently increase vaccination rates during pregnancy. As a result, reconsideration of previously evaluated strategies to address influenza vaccine hesitancy during pregnancy is needed. Given the population health benefits maternal influenza immunization can offer research and investment into innovative and effective, multilevel interventions remains vital to support global maternal and infant health.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lafond KE, Porter RM, Whaley MJ, Suizan Z, Ran Z, Aleem MA, Thapa B, Sar B, Proschle VS, Peng Z, et al. Global burden of influenza-associated lower respiratory tract infections and hospitalizations among adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2021;18(3):e1003550. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003550.

- Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, Muscatello DJ, Palekar R, Tempia S, Cohen C, Gran JM, Schanzer D, Cowling BJ, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1285–11. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2.

- Mertz D, Lo CK, Lytvyn L, Ortiz JR, Loeb M. Pregnancy as a risk factor for severe influenza infection: an individual participant data meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):683. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4318-3.

- Siston AM, Rasmussen SA, Honein MA, Fry AM, Seib K, Callaghan WM, Louie, J, Doyle, TJ, Crockett, M, Lynfield, R, et al. Pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus illness among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA. 2010;303(15):1517–25. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.479.

- Louie JK, Acosta M, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA. Severe 2009 H1N1 influenza in pregnant and postpartum women in California. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):27–35. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0910444.

- Fell DB, Savitz DA, Kramer MS, Gessner BD, Katz MA, Knight M, Luteijn JM, Marshall H, Bhat N, Gravett MG, et al. Maternal influenza and birth outcomes: systematic review of comparative studies. BJOG. 2017;124(1):48–59. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14143.

- Dawood FS, Kittikraisak W, Patel A, Rentz Hunt D, Suntarattiwong P, Wesley MG, Thompson MG, Soto G, Mundhada S, Arriola CS, et al. Incidence of influenza during pregnancy and association with pregnancy and perinatal outcomes in three middle-income countries: a multisite prospective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):97–106. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30592-2.

- Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Griffin MR, Szilagyi PG, Staat MA, Iwane MK, Snively BM, Suerken CK, Hall CB, Weinberg GA, et al. The burden of influenza in young children, 2004–2009. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):207–16. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1255.

- Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Weinberg GA, Szilagyi P, Staat MA, Iwane MK, Bridges CB, Grijalva CG, Zhu Y, Bernstein DI, et al. The underrecognized burden of influenza in young children. New Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):31–40. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054869.

- Shang M, Blanton L, Brammer L, Olsen SJ, Fry AM. Influenza-associated pediatric deaths in the United States, 2010–2016. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4). doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2918.

- Thompson MG, Kwong JC, Regan AK, Katz MA, Drews SJ, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Klein NP, Chung H, Effler PV, Feldman BS, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza-associated hospitalizations during pregnancy: a multi-country retrospective test negative design study, 2010–2016. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(9):1444–53. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy737.

- Omer SB. Maternal immunization. New Engl J Med. 2017;376(13):1256–67. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1509044.

- Wilson RJ, Paterson P, Jarrett C, Larson HJ. Understanding factors influencing vaccination acceptance during pregnancy globally: a literature review. Vaccine. 2015;33(47):6420–29. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.046.

- MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Ortiz JR, Perut M, Dumolard L, Wijesinghe PR, Jorgensen P, Ropero AM, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Heffelfinger JD, Tevi-Benissan C, Teleb NA, et al. A global review of national influenza immunization policies: analysis of the 2014 WHO/UNICEF joint reporting form on immunization. Vaccine. 2016;34(45):5400–05. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.07.045.

- Irving SA, Ball SW, Booth SM, Regan AK, Naleway AL, Buchan SA, Katz MA, Effler PV, Svenson LW, Kwong JC, et al. A multi-country investigation of influenza vaccine coverage in pregnant individuals, 2010–2016. Vaccine. 2021;39(52):7598–605. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.018.

- Razzaghi H, Kahn KE, Black CL, Lindley MC, Jatlaoui TC, Fiebelkorn AP, Havers FP, D’Angelo DV, Cheung A, Ruther NA, et al. Influenza and Tdap vaccination coverage among pregnant women — United States, April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(39):1391–97. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6939a2.

- McHugh L, Van Buynder P, Sarna M, Andrews RM, Moore HC, Binks MJ, Pereira G, Blyth CC, Lust K, Foo D, et al. Timing and temporal trends of influenza and pertussis vaccinations during pregnancy in three Australian jurisdictions: the Links2HealthierBubs population-based linked cohort study, 2012–2017. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;in press. doi:10.1111/ajo.13548.

- McRae JE, Dey A, Carlson S, Sinn J, McIntyre P, Beard F, Macartney K, Wood N. Influenza vaccination among pregnant women in two hospitals in Sydney, NSW: what we can learn from women who decline vaccination. Public Health Res Pract. 2022;32(2). doi:10.17061/phrp31232111.

- Walker JL, Rentsch CT, McDonald HI, Bak J, Minassian C, Amirthalingam G, Edelstein M, Thomas S. Social determinants of pertussis and influenza vaccine uptake in pregnancy: a national cohort study in England using electronic health records. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6):e046545. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046545.

- Kilich E, Dada S, Francis MR, Tazare J, Chico RM, Paterson P, Larson HJ. Factors that influence vaccination decision-making among pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0234827. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234827.

- Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2(4):328–35. doi:10.1177/109019817400200403.

- Okoli GN, Reddy VK, Al-Yousif Y, Neilson CJ, Mahmud SM, Abou-Setta AM. Sociodemographic and health-related determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence since 2000. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(6):997–1009. doi:10.1111/aogs.14079.

- Myers KL. Predictors of maternal vaccination in the United States: an integrative review of the literature. Vaccine. 2016;34(34):3942–49. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.042.

- Foppa IM, Ferdinands JM, Chung J, Flannery B, Fry AM. Vaccination history as a confounder of studies of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine X. 2019;1:100008. doi:10.1016/j.jvacx.2019.100008.

- Raut S, Apte A, Srinivasan M, Dudeja N, Dayma G, Sinha B, Bavdekar A. Determinants of maternal influenza vaccination in the context of low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0262871. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262871.

- Vilca LM, Verma A, Buckeridge D, Campins M. A population-based analysis of predictors of influenza vaccination uptake in pregnant women: the effect of gestational and calendar time. Prev Med. 2017;99:111–17. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.02.010.

- Hutcheon JA, Savitz DA. Invited commentary: influenza, influenza immunization, and pregnancy—it’s about time. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184(3):187–91. doi:10.1093/aje/kww042.

- Brixner A, Brandstetter S, Böhmer MM, Seelbach-Göbel B, Melter M, Kabesch M, Apfelbacher C. Prevalence of and factors associated with receipt of provider recommendation for influenza vaccination and uptake of influenza vaccination during pregnancy: cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):723. doi:10.1186/s12884-021-04182-w.

- Yuen CY, Tarrant M. Determinants of uptake of influenza vaccination among pregnant women – a systematic review. Vaccine. 2014;32(36):4602–13. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.067.

- Rand CM, Bender R, Humiston SG, Albertin C, Olson-Chen C, Chen J, Hsu YSJ, Vangala S, Szilagyi PG. Obstetric provider attitudes and office practices for maternal influenza and Tdap vaccination. J Womens Health. 2022;31(9):1246–54. doi:10.1089/jwh.2022.0030.

- ECDC. Seasonal influenza vaccination and antiviral use in EU/EEA member states – overview of vaccine recommendations for 2017–2018 and vaccination coverage rates for 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 influenza seasons. Stockholm: ECDC; 2018.

- Young A, Charania NA, Gauld N, Norris P, Turner N, Willing E. Knowledge and decisions about maternal immunisation by pregnant women in Aotearoa New Zealand. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):779. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08162-4.

- Brillo E, Ciampoletti M, Tosto V, Buonomo E. Exploring Tdap and influenza vaccine uptake and its determinants in pregnancy: a cross-sectional study. Ann Ig. 2022;34(4):358–74. doi:10.7416/ai.2022.2503.

- Albattat HS, Alahmed AA, Alkadi FA, Aldrees OS. Knowledge, attitude, and barriers of seasonal influenza vaccination among pregnant women visiting primary healthcare centers in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia. 2019/2020. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(2):783–90. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2183_20.

- Wang J, Sun D, Abudusaimaiti X, Vermund SH, Li D, Hu Y. Low awareness of influenza vaccination among pregnant women and their obstetricians: a population-based survey in Beijing, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(11):2637–43. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1596713.

- Henninger ML, Irving SA, Thompson M, Avalos LA, Ball SW, Shifflett P, Naleway AL. Factors associated with seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnant women. J Womens Health. 2015;24(5):394–402. doi:10.1089/jwh.2014.5105.

- MacDougall DM, Halperin SA. Improving rates of maternal immunization: challenges and opportunities. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(4):857–65. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1101524.

- Regan AK, Mak DB, Hauck YL, Gibbs R, Tracey L, Effler PV. Trends in seasonal influenza vaccine uptake during pregnancy in Western Australia: implications for midwives. Women Birth. 2016;29(5):423–29. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2016.01.009.

- Callahan AG, Coleman-Cowger VH, Schulkin J, Power ML. Racial disparities in influenza immunization during pregnancy in the United States: a narrative review of the evidence for disparities and potential interventions. Vaccine. 2021;39(35):4938–48. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.028.

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 732: influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(4):e109–14. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002588.

- Wu P, Griffin MR, Richardson A, Gabbe SG, Gambrell MA, Hartert TV. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy: opinions and practices of obstetricians in an urban community. South Med J. 2006;99(8):823–28. doi:10.1097/01.smj.0000231262.88558.8e.

- CDC. Influenza vaccination in pregnancy: practices among obstetrician-gynecologists--United States, 2003-04 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(41):1050–52.

- Ricco M, Vezzosi L, Gualerzi G, Balzarini F, Capozzi VA, Volpi L. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of obstetrics-gynecologists on seasonal influenza and pertussis immunizations in pregnant women: preliminary results from North-Western Italy. Minerva Ginecol. 2019;71(4):288–97. doi:10.23736/S0026-4784.19.04294-1.

- Dvalishvili M, Mesxishvili D, Butsashvili M, Kamkamidze G, McFarland D, Bednarczyk RA. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of healthcare providers in the country of Georgia regarding influenza vaccinations for pregnant women. Vaccine. 2016;34(48):5907–11. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.033.

- Noh JY, Seo YB, Song JY, Choi WS, Lee J, Jung E, Kang S, Choi MJ, Jun J, Yoon JG, et al. Perception and attitudes of Korean obstetricians about maternal influenza vaccination. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(7):1063–68. doi:10.3346/jkms.2016.31.7.1063.

- Kissin DM, Power ML, Kahn EB, Williams JL, Jamieson DJ, MacFarlane K, Schulkin J, Zhang Y, Callaghan WM. Attitudes and practices of obstetrician–gynecologists regarding influenza vaccination in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1074–80. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182329681.

- Power ML, Leddy MA, Anderson BL, Gall SA, Gonik B, Schulkin J. Obstetrician–gynecologists’ practices and perceived knowledge regarding immunization. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(3):231–34. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.019.

- Ishola DA Jr., Permalloo N, Cordery RJ, Anderson SR. Midwives’ influenza vaccine uptake and their views on vaccination of pregnant women. J Public Health (Oxf). 2013;35(4):570–77. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fds109.

- Wilcox CR, Little P, Jones CE. Current practice and attitudes towards vaccination during pregnancy: a survey of GPs across England. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(692):e179–85. doi:10.3399/bjgp20X708113.

- Krishnaswamy S, Wallace EM, Buttery J, Giles ML. A study comparing the practice of Australian maternity care providers in relation to maternal immunisation. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;59(3):408–15. doi:10.1111/ajo.12888.

- Arreciado Marañón A, Fernández-Cano MI, Montero-Pons L, Feijoo-Cid M, Reyes-Lacalle A, Cabedo-Ferreiro RM, Manresa-Domínguez JM, Falguera-Puig G. Knowledge, perceptions, attitudes and practices of midwives regarding maternal influenza and pertussis vaccination: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8391. doi:10.3390/ijerph19148391.

- Pringle W, Greyson D, Graham JE, Dubé È, Mitchell H, Trottier M, Berman R, Russell ML, MacDonald SE, Bettinger JA. Suitable but requiring support: how the midwifery model of care offers opportunities to counsel the vaccine hesitant pregnant population. Vaccine. 2022;40(38):5594–600. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.07.055.

- Smith SE, Gum L, Thornton C. An exploration of midwives’ role in the promotion and provision of antenatal influenza immunisation: a mixed methods inquiry. Women Birth. 2021;34(1):e7–13. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2020.04.009.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, Kaminsky K, Green CR, Ouakki M, Bettinger JA, Brousseau N, Castillo E, Crowcroft NS, Driedger SM, et al. Vaccination during pregnancy: canadian maternity care providers’ opinions and practices. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(11):2789–99. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1735225.

- Gauld N, Martin S, Sinclair O, Petousis-Harris H, Dumble F, Grant CC. Influences on pregnant women’s and health care professionals’ behaviour regarding maternal vaccinations: a qualitative interview study. Vaccines. 2022;10(1):76. doi:10.3390/vaccines10010076.

- US Department of Health and Human Sevices. Social Determinants of Health. Healthy People 2030; 2022. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health.

- Kiefer MK, Mehl R, Costantine MM, Landon MB, Bartholomew A, Mallampati D, Manuck T, Grobman W, Rood KM, Venkatesh KK. Association between social vulnerability and influenza and tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccination in pregnant and postpartum individuals. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2022;4(3):100603. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2022.100603.

- Chan HJ, Chang JY, Erickson SR, Wang CC. Influenza vaccination among pregnant women in the United States: findings from the 2012–2016 national health interview survey. J Womens Health. 2019;28(7):965–75. doi:10.1089/jwh.2018.7139.

- Cambou MC, Copeland TP, Nielsen-Saines K, Macinko J. Insurance status predicts self-reported influenza vaccine coverage among pregnant women in the United States: a cross-sectional analysis of the national health interview study data from 2012 to 2018. Vaccine. 2021;39(15):2068–73. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.026.

- Kaur R, Callaghan T, Regan AK. Disparities in prenatal immunization rates in rural and urban US areas by indicators of access to care. J Rural Health. 2022. doi:10.1111/jrh.12647.

- Wendling A, Taglione V, Rezmer R, Lwin P, Frost J, Terhune J, Kerver J. Access to maternity and prenatal care services in rural Michigan. Birth. 2021;48(4):566–73. doi:10.1111/birt.12563.

- Sullivan MH, Denslow S, Lorenz K, Dixon S, Kelly E, Foley KA. Exploration of the effects of rural obstetric unit closures on birth outcomes in North Carolina. J Rural Health. 2021;37(2):373–84. doi:10.1111/jrh.12546.

- Kaur R, Callaghan T, Regan AK. Disparities in maternal influenza immunization among women in rural and urban areas of the United States. Prev Med. 2021;147:106531. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106531.

- Arnold LD, Luong L, Rebmann T, Chang JJ. Racial disparities in U.S. maternal influenza vaccine uptake: results from analysis of Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data, 2012–2015. Vaccine. 2019;37(18):2520–26. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.02.014.

- Ahluwalia IB, Ding H, Harrison L, D’Angelo D, Singleton JA, Bridges C. Disparities in influenza vaccination coverage among women with live-born infants: pRAMS surveillance during the 2009–2010 influenza season. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(5):408–16. doi:10.1177/003335491412900504.

- Dudley MZ, Limaye RJ, Salmon DA, Omer SB, O’Leary ST, Ellingson MK, Spina CI, Brewer SE, Bednarczyk RA, Malik F, et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities in maternal vaccine knowledge, attitudes, and intentions. Public Health Rep. 2021;136(6):699–709. doi:10.1177/0033354920974660.

- Gary FA, Thiese S, Hopps J, Hassan M, Still CH, Brooks LM, Prather, S, Yarandi, H. Medical mistrust among Black women in America. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2021;32:10–15.

- Morgan KM, Maglalang DD, Monnig MA, Ahluwalia JS, Avila JC, Sokolovsky AW. Medical mistrust, perceived discrimination, and race: a longitudinal analysis of redictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in US Adults. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;1–10. doi:10.1007/s40615-022-01368-6.

- WHO. Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper – November 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87(47):461–76.

- Krishnaswamy S, Lambach P, Giles ML. Key considerations for successful implementation of maternal immunization programs in low and middle income countries. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(4):942–50. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1564433.

- Gambrell A, Sundaram M, Bednarczyk RA. Estimating the number of US children susceptible to measles resulting from COVID-19-related vaccination coverage declines. Vaccine. 2022;40(32):4574–79. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.06.033.

- Onimoe G, Angappan D, Chandar MCR, Rikleen S. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on well child care and vaccination. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:873482. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.873482.

- Moura C, Truche P, Sousa Salgado L, Meireles T, Santana V, Buda A, Bentes A, Botelho F, Mooney D. The impact of COVID-19 on routine pediatric vaccination delivery in Brazil. Vaccine. 2022;40(15):2292–98. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.076.

- Ji C, Piche-Renaud PP, Apajee J, Stephenson E, Forte M, Friedman JN, Science M, Zlotkin S, Morris SK, Tu K. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on routine immunization coverage in children under 2 years old in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective cohort study. Vaccine. 2022;40(12):1790–98. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.008.

- MacDonald SE, Paudel YR, Kiely M, Rafferty E, Sadarangani M, Robinson JL, Driedger SM, Svenson LW. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on vaccine coverage for early childhood vaccines in Alberta, Canada: a population-based retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e055968. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055968.

- Walker B, Anderson A, Stoecker C, Shao Y, LaVeist TA, Callison K. COVID-19 and routine childhood and adolescent immunizations: evidence from Louisiana Medicaid. Vaccine. 2022;40(6):837–40. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.12.022.

- Kim S, Headley TY, Tozan Y. Universal healthcare coverage and health service delivery before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a difference-in-difference study of childhood immunization coverage from 195 countries. PLoS Med. 2022;19(8):e1004060. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1004060.

- Skirrow H, Barnett S, Bell S, Mounier-Jack S, Kampmann B, Holder B. Women’s views and experiences of accessing pertussis vaccination in pregnancy and infant vaccinations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-methods study in the UK. Vaccine. 2022;40(34):4942–54. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.06.076.

- Saso A, Skirrow H, Kampmann B. Impact of COVID-19 on immunization services for maternal and infant vaccines: results of a survey conducted by imprint—the immunising pregnant women and infants network. Vaccines. 2020;8(3):556. doi:10.3390/vaccines8030556.

- Bruno S, Nachira L, Villani L, Beccia V, Di Pilla A, Pascucci D, Quaranta G, Carducci B, Spadea A, Damiani G, et al. Knowledge and beliefs about vaccination in pregnant women before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2022;10:903557. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.903557.

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–77. doi:10.1177/109019818801500401.

- Bisset KA, Paterson P. Strategies for increasing uptake of vaccination in pregnancy in high-income countries: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2018;36(20):2751–59. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.013.

- Wong VWY, Fong DYT, Lok KYW, Wong JYH, Sing C, Choi AY, Yuen CYS, Tarrant M. Brief education to promote maternal influenza vaccine uptake: a randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2016;34(44):5243–50. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.09.019.

- Frew PM, Kriss JL, Chamberlain AT, Malik F, Chung Y, Cortés M, Omer SB. A randomized trial of maternal influenza immunization decision-making: a test of persuasive messaging models. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2016;12(8):1989–96. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016.1199309.

- Chamberlain AT, Seib K, Ault KA, Rosenberg ES, Frew PM, Cortés M, Whitney EAS, Berkelman RL, Orenstein WA, Omer SB. Improving influenza and Tdap vaccination during pregnancy: a cluster-randomized trial of a multi-component antenatal vaccine promotion package in late influenza season. Vaccine. 2015;33(30):3571–79. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.048.

- Chamberlain AT, Seib K, Ault KA, Rosenberg ES, Frew PM, Cortes M, Whitney EAS, Berkelman RL, Orenstein WA, Omer SB. Impact of a multi-component antenatal vaccine promotion package on improving knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about influenza and Tdap vaccination during pregnancy. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2016;12(8):2017–24. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1127489.

- Hoppe KK, Eckert LO. Achieving high coverage of H1N1 influenza vaccine in an ethnically diverse obstetric population: success of a multifaceted approach. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:746214. doi:10.1155/2011/746214.

- Panda B, Stiller R, Panda A. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy and factors for lacking compliance with current CDC guidelines. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(3):402–06. doi:10.3109/14767058.2010.497882.

- Bushar JA, Kendrick JS, Ding H, Black CL, Greby SM. Text4baby influenza messaging and influenza vaccination among pregnant women. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(6):845–53. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2017.06.021.

- Goodman K, Mossad SB, Taksler GB, Emery J, Schramm S, Rothberg MB. Impact of video education on influenza vaccination in pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 2015;60:471–79.

- Meharry PM, Cusson RM, Stiller R, Vázquez M. Maternal influenza vaccination: evaluation of a patient-centered pamphlet designed to increase uptake in pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(5):1205–14. doi:10.1007/s10995-013-1352-4.

- Kriss JL, Frew PM, Cortes M, Malik FA, Chamberlain AT, Seib K, Flowers L, Ault KA, Howards PP, Orenstein WA, et al. Evaluation of two vaccine education interventions to improve pertussis vaccination among pregnant African American women: a randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2017;35(11):1551–58. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.01.037.

- Gagneur A. Motivational interviewing: a powerful tool to address vaccine hesitancy. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2020;46(04):93–97. doi:10.14745/ccdr.v46i04a06.

- Miller WR. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behav Cogn Psychother. 1983;11(2):147–72. doi:10.1017/S0141347300006583.

- Gregory EF, Maddox AI, Levine LD, Fiks AG, Lorch SA, Resnicow K. Motivational interviewing to promote interconception health: a scoping review of evidence from clinical trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(11):3204–12. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2022.07.009.

- Lim D, Schoo A, Lawn S, Litt J. Embedding and sustaining motivational interviewing in clinical environments: a concurrent iterative mixed methods study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):164. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1606-y.

- Brewer SE, Cataldi JR, Fisher M, Glasgow RE, Garrett K, O’Leary ST. Motivational Interviewing for Maternal Immunisation (MI4MI) study: a protocol for an implementation study of a clinician vaccine communication intervention for prenatal care settings. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e040226. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040226.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. New York (NY): Guildford Press; 2012.

- Gagneur A, Battista MC, Boucher FD, Tapiero B, Quach C, De Wals P, Lemaitre, T, Farrands, A, Boulianne, N, Sauvageau, C, et al. Promoting vaccination in maternity wards ─ motivational interview technique reduces hesitancy and enhances intention to vaccinate, results from a multicentre non-controlled pre- and post-intervention RCT-nested study, Quebec, March 2014 to February 2015. Euro Surveill. 2019;24:1800641.

- Jamison KC, Ahmed AH, Spoerner DA, Kinney D. Best shot: a motivational interviewing approach to address vaccine hesitancy in pediatric outpatient settings. J Pediatr Nurs. 2022;67:124–31. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2022.08.012.

- Cole JW, A MHC, McGuire K, Berman S, Gardner J, Teegala Y. Motivational interviewing and vaccine acceptance in children: the MOTIVE study. Vaccine. 2022;40(12):1846–54. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.01.058.

- Stockwell MS, Westhoff C, Kharbanda EO, Vargas CY, Camargo S, Vawdrey DK, Castaño PM. Influenza vaccine text message reminders for urban, low-income pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2014;Suppl 104(S1):e7–12. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301620.

- Frew PM, Saint-Victor DS, Owens LE, Omer SB. Socioecological and message framing factors influencing maternal influenza immunization among minority women. Vaccine. 2014;32(15):1736–44. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.030.

- Yudin MH, Mistry N, De Souza LR, Besel K, Patel V, Blanco Mejia S, Bernick R, Ryan V, Urquia M, Beigi RH, et al. Text messages for influenza vaccination among pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2017;35(5):842–48. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.002.

- Regan AK, Bloomfield L, Peters I, Effler PV. Randomized controlled trial of text message reminders for increasing influenza vaccination. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(6):507–14. doi:10.1370/afm.2120.

- Roussos-Ross D, Prieto A, Goodin A, Watson AK, Bright MA. Increased Tdap and influenza vaccination acquisition among patients participating in group prenatal care. J Prim Prev. 2020;41(5):413–20. doi:10.1007/s10935-020-00606-z.

- Marcell L, Dokania E, Navia I, Baxter C, Crary I, Rutz S, Soto Monteverde MJ, Simlai S, Hernandez C, Huebner EM, et al. One Vax Two Lives: a social media campaign and research program to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(5):685–95. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.06.022.

- Mohammed H, McMillan M, Roberts CT, Marshall HS. A systematic review of interventions to improve uptake of pertussis vaccination in pregnancy. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0214538. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0214538.