ABSTRACT

The seasonal influenza vaccine coverage remains suboptimal among children even though guardians expressed high willingness to vaccinate their children. This study aimed to determine the association between vaccine hesitancy and uptake to facilitate vaccination; thus, bridging the gap. A cross-sectional design, using stratified cluster random sampling, was conducted among guardians of 0–59-month-old Chinese children from July to October in 2019. A structural equation model was applied to explore the interrelationships between factors including vaccine hesitancy, vaccination, social influence, and relative knowledge among guardians. Of the 1,404 guardians, 326 were highly hesitant to vaccinate their children, 33.13% (108/326) of whom had vaccinated their children. Moreover, 517 and 561 guardians had moderate and low vaccine hesitancy, with corresponding vaccine coverage of 42.75% (221/517) and 47.95% (269/516). Guardians’ gender, age, and education level were demographic variables with significant moderating effects. Social influence considered impact of communities, family members, friends, neighbors, healthcare workers, bad vaccination experience and sense on price. Actual vaccine uptake was negatively significantly associated with hesitancy (β = -0.11, p < .001) with positive association with social influence (β = 0.61, p < .001). Vaccine hesitancy was negatively significantly associated with relative knowledge (β = -2.14, p < .001) and social influence (β = -1.09, p < .001). A gap is noted between cognitions and behaviors among children’s guardians regarding influenza vaccination. A comprehensive strategy including emphasizing benefits of the influenza vaccination, risk of infection, and ensuring high vaccine confidence among healthcare workers can help transform the willingness to engage in the behavior of vaccination.

Introduction

Seasonal influenza, an acute viral infection caused by influenza viruses, spreads globally each year, leading to three to five million cases of severe illness.Citation1 To illustrate, 29000 to 650,000 respiratory deaths globally were due to influenza in 2018.Citation2,Citation3 Due to immunologic barrier, children are considered as one of the most susceptible groups to acquire influenza infection.Citation4 Influenza may lead to hospitalizations for lower respiratory infection, nonspecific febrile illness, or central nervous system complications in children.Citation4 A systematic review of influenza-associated hospitalizations among children demonstrated that influenza infection resulted in nearly one million worldwide hospitalizations among children aged <5 years annually from 1982 to 2012.Citation5 The admission rates could reach up to a high-intensity level of more than 8 per 10,000 population among children aged 0–5 years old during peak seasons in 2019 in Hong Kong China.Citation6 A study in China estimated that children of 0–4 years old had the highest attack rate of 31.9% compared to general population.Citation7

The seasonal influenza vaccine is the most effective tool to prevent influenza and its complications.Citation8 Yet, the current National Immunization Program (NIP) in China has not included the influenza vaccine.Citation8 The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDCP) developed the Introduction of Seasonal Influenza Vaccination in China, 2020–2021(ISIVC) to decrease the risk of severe infections and complications caused by the influenza virus infection.Citation9 The CCDCP recommends annual administration of the seasonal influenza vaccine to children 6–59 months of age.Citation9 Despite the development of the 2020–2021 recommendation, the coverage of vaccine uptake among children aged 6–59 months remained low, varying from 8.6% to 26.4% between the 2009–2010 and 2012–2013 influenza seasons and 28.4% (95% CI: 23.6–33.2%) in the 2018–2019 season in China.Citation8

Vaccine hesitancy (VH), which is believed to be responsible for decreasing vaccine coverage, was reported as one of the top ten public health threats by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2019.Citation8 According to the WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE), VH refers to the delay in the acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite the availability of vaccination services, and is complex and context-specific.Citation10 Specifically, VH as defined by SAGE as the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate, a behavior-based definition, was controversial without a robust theory base and was not emphasizing the practical (or access) barriers to vaccination uptake.Citation11–13 In practice, VH is conceptualized as attitude or cognition toward vaccination (i.e. positive, negative, or neutral on vaccination).Citation14–17 And the experience of vaccination was used to describe VH (i.e., having been vaccinated, having not been vaccinated, or delaying to be vaccinated) as past behavior being identified as a strong predictor of influenza vaccine acceptance and as a decision-making process on vaccination if vaccines are available (i.e., being undecided, indecisive, or not yet having made a decision or plan to vaccinate soon).Citation1,Citation8,Citation18,Citation19 The concept of VH, which was a complex and multifactorial continuum of hesitancy between vaccine acceptance and refusal, increasingly gained traction.Citation20 VH has prompted more attention to the fact that, as for all behaviors, vaccination attitudes and decisions should be seen on a continuum, ranging from a small number of vaccine-resistant individuals to a majority who accept to be vaccinated.Citation12 According to the survey of willingness and behavior in the vaccination among the elderly conducted in Shanghai, China, vaccination uptake was inconsistent with VH among persons aged 50–69 years.Citation21 Additionally, guardians expressed high willingness or cognition to obtain the influenza vaccine for their children but the coverage of vaccination uptake remained low (54.2% of willingness vs 38.3% of vaccination globally, 74.2% and 80.5% of willingness in 2018 and 2019 vs 49.4% of vaccination in the USA).Citation21–23 Therefore, we aimed to facilitate bridging the gap between cognitions and behaviors among guardians by determining the interrelationships between vaccine uptake of influenza, hesitancy, and factors including social influence and knowledge.

Materials and methods

Survey design and participants

This is a secondary analysis and the details are presented in the prior protocol.Citation8

Measures

The questionnaire used in this study was divided into four sections: (1) socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age, residence with response options of urban and rural, education level with response options of High/secondary school, Junior college, Bachelor or higher, annual household income with response options of RMB<50K, <100K, <200K), (2) vaccination behaviors (VB) and VH, (3) knowledge on influenza and influenza vaccination, and (4) social influence.

Vaccination behaviors and vaccine hesitancy

VB: Children who had already been vaccinated against the influenza in previous seasons were considered as the vaccinated. Guardians were asked whether their children had been vaccinated with the influenza vaccine before.

VH: Three conceptualizations of VH (attitudes or cognitions, behaviors, and prediction to make decisions) were used to describe VH. To explore the gap between cognitions and behaviors against the influenza among guardians, we identified VH as attitudes or cognitions on vaccination, using the Modified Vaccine Hesitancy scale to quantify VH.

The Modified Vaccine Hesitancy Scale: This scale based on the Health Belief Model was used to measure VH, including perceived risk, benefit, and barrier. Perceived risk was measured using the following questions: (1) Influenza is a great threat to my child’s health and (2) Child has high risk of getting influenza. Perceived benefit was measured using the following questions: (1) Influenza vaccine is necessary to prevent my children from getting influenza, (2) Influenza vaccine is effective to prevent influenza, (3) Influenza vaccine has protective effect for the unvaccinated around the vaccines, and (4) Influenza vaccine is safe. Perceived barrier was measured using the following questions: (1) Influenza vaccine is expensive for me; and (2) I can easily find time taking my children to the clinic for influenza vaccines. The responses were provided on a five-point Likert scale. Then, scores from eight questions were added together to get the total score, stratified by VH score using trisection: high hesitancy (<28), moderate hesitancy (28 ~ 30), and low hesitancy (≥31). A higher score indicated a lower level of VH. Perceived risk was divided into two levels, using P50: high(≥8) or low(<8). Perceived barrier was divided into two levels, using the cut-half value: high (≥7) or low (<7). Perceived benefit was divided into two levels, using the cut-half value: high (≥16) or low (<16).

Knowledge on influenza and influenza vaccination

Four questions were included to measure: (1) I know that influenza is different from common cold; (2) I think that influenza vaccine can only prevent influenza; (3) I know that government recommends influenza vaccination; and (4) I know that influenza vaccine is recommended to be vaccinated annually. Respondents were asked to answer “yes” or “no.”

Social influence

Regarding social influence, six questions were included: (1) promotion by communities, (2) family members’ attitudes to children getting influenza vaccine, (3) friends and neighbors’ attitudes to children getting influenza vaccine, (4) healthcare workers (HCWs)’ attitudes to children getting influenza vaccine, (5) bad vaccination experience, and (6) sense on price of influenza vaccine.

Statistical analysis

We used IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0 and IBM SPSS AMOS, version 23.0 (Corporation, New York, NY, United States) for analysis. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. The proportions of categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test or Pearson’s chi-square test. Logistic regression was used to measure behaviors to vaccination, only considering variables with significant associations with behaviors to vaccinate (p < .1). The associations were reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) after adjustment for potential confounders, including socio-demographic characteristics and VH. Then, data was stratified by confounding factors including gender, age, residence, education level, and annual household income. A structural equation model (SEM) was established by taking vaccine uptake as internal variables and social influence, relative knowledge and VH as external variables to determine the interrelationships between them among guardians. Five indices were used to evaluate if the proposed model was supported (). The indices included the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), parsimony normed fit index (PNFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).Citation21 The level of the GFI and AGFI should be >0.9, the level of the CFI should be >0.8, the level of the PNFI should be >0.5, and the RMSEA should be <0.08, respectively. When the fit indices are satisfactory, the path coefficients in the SEM are further scrutinized.Citation21 All tests were two-tailed, and P-values less than 0.05 or a 95% CI were considered statistically significant.

Table 1. Demographic profiles and vaccination behavior.

Results

Overall, 1,489 participants were recorded, of whom 1,404 respondents were retained for analysis as 85 guardians did not complete the questionnaires.

Demographic characteristic of vaccination behaviors

Among 1,404 guardians in this sample, 972 (69.23%) were female, 501 (35.68%) were aged under 30 years old, 716 (50.99%) lived in an urban area, and 942 (67.09%) had a college education degree or higher. Furthermore, 326 (23.22%) guardians were highly hesitant to receive influenza vaccination for their children and 33.13% (108/326) of them had vaccinated their children. Five hundred and seventeen(36.82%) showed moderate VH and 42.75% (221/517) had vaccinated their children and 561 (39.96%) showed low VH and 47.95% (269/516) had vaccinated their children. Moreover, 42.59% (598/1404) of guardians had vaccinated their children (). The vaccination rate of highly resistant parents was significantly lower than that among parents with low or moderate vaccine hesitancy (χ2 = 18.53, p < .001).

Determinants of vaccination behaviors

Variables of guardians’ gender (aOR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.01–1.63), age group (30–40: aOR : 1.32, 95% CI: 1.04–1.67;≥40: aOR: 2.22, 95% CI: 1.28–3.85), education level (junior college: aOR:0.67, 95% CI: 0.52–0.87; bachelor or higher: aOR:0.47, 95%CI: 0.29–0.76), and perceived benefit (aOR: 1.64, 95% CI: 1.21–2.24) were related to having VB ().

After stratifying for confounders including gender, age, residence, education level and annual household income, VB was associated with VH and perceived benefit (p <.05). Furthermore, VB was associated with perceived risk among guardians with junior college education (χ2 = 9.26, p = .002) ().

Table 2. Vaccine hesitancy and actual uptake stratified by demographic profiles.

Table 3. Perceived risk, perceived benefit and actual uptake stratified by demographic profiles.

Table 4. Indexes of model fitness for the structural equation model.

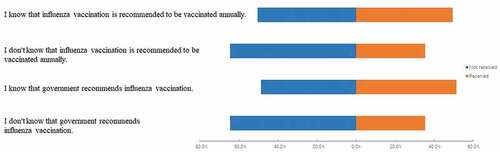

Those who know that government recommends influenza vaccination (χ2 = 35.88, p < .001) and that the influenza vaccine is recommended to be taken annually (χ2 = 28.38, p < .001) were more likely to vaccinate their children ().

Figure 1. Knowledge on influenza and influenza vaccination (p < .001).

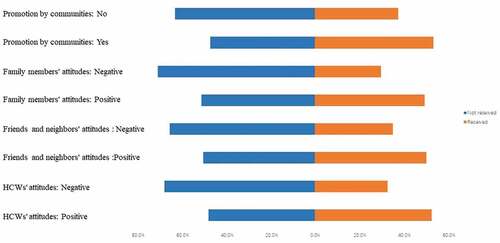

Those who reported that their communities promote influenza vaccination (χ2 = 31.63, p < .001), with support of their family members (χ2 = 49.26, p < .001), friends and neighbors (χ2 = 32.23, p < .001), and HCWs (χ2 = 56.00, p < .001) were more likely to vaccinate their children ().

Structural equation model

The SEM model demonstrated a well-fitted model, as supported by all of the fit indices (GFI = 0.933; AGFI = 0.912; CFI = 0.890; PNFI = 0.729; and RMSEA = 0.060) (). The SEM model further showed that actual vaccination uptake was significantly associated with VH (β = -0.11, p < .001) and social influence (β = 0.61, p < .001). Moreover, VH was significantly associated with relative knowledge (β = -2.14, p < .001) and social influence (β = -1.09, p < .001). Social influence was significantly associated with relative knowledge (β = 0.07, p < .001) and perceived benefit (β = 1.99, p < .001), barrier (β = -0.66, p < .001), and risk (β = 0.77, p < .001) ( and ).

Table 5. Path diagram of knowledge, social influence, perceived benefit, perceived risk, perceived barrier, vaccine hesitancy and influenza vaccination.

Discussion

We employ a cross-sectional design among children’s guardians to find that cognitions are inconsistent with behaviors of influenza vaccination, implying that there is a gap between them. Moreover, vaccine hesitancy, social influence, and relative knowledge play an essential role in actual vaccination activity.

According to our survey, coverage of the influenza vaccine in China among children remains low compared to USA and Australia.Citation24,Citation25 Over half of the guardians with low VH do not vaccinate their children in this analysis even though VH can be a predictive indicator of coverage figures. Santibanez et al. report that association between VH and influenza vaccination coverage may suggest a positive role for reduction of VH in increasing vaccination coverage.Citation26 They provide the evidence that the vaccination rate is not only affected by acceptance but also by logistics or opportunity-related factors.Citation13,Citation26 We observe that the gap between VH and VB is widespread, according to the stratified analysis, especially across female sex, young guardians, low-income families, and parents with low education levels. Therefore, according to VB should be consistent with the intention to vaccinate children among females, young guardians, low-income guardians and guardians with low education levels. Elimination on the gap between willingness and behavior can be taken by reducing the economic burden of vaccines for low-income families and promoting guardians with lower education levels to turn vaccination intention into vaccination behavior; thus, leading to guardians vaccinating their children.Citation4 Access (ie, the ability of individuals to be reached by, or to reach, recommended vaccines) and affordability (ie, the ability of individuals to afford vaccination, in terms of both financial and nonfinancial costs) are summarized into 5A factors influencing vaccine uptake.Citation13 The surplus fund in individual medical savings account of basic social medical insurance (BSMI) in Ningbo China could be used to pay for the influenza vaccination of the insured persons and their families.Citation27 Also, it has been previously documented that vaccine hesitancy is associated with worse service accessibility and high sensitivity of adverse reactions.Citation9,Citation21 Our data show that the decision for guardians to vaccinate their children is based on balancing benefit and risk perceptions on influenza infection or adverse effects from vaccination. The significant gap between cognitions and behaviors against influenza may be due to an imbalance between the high sensitivity to risk of the influenza infection, leading to increased willingness to vaccinate children among guardians, and availability and accessibility of the influenza vaccine.Citation28

In our study, guardians’ gender, age, education level, related knowledge, and social influence take effects on vaccination. We find that males are more likely to vaccinate their children than females, consistent with previous studies.Citation29–31 Specifically, vaccine uptake has been observed to be influenced by education of parents among guardians with lower education.Citation32 Furthermore, data show that it is more difficult for the young parents to coordinate time of vaccination for children and their work leading to low vaccination.Citation22,Citation33 Coverage of the influenza vaccine remains low among low-income guardians even though they have a positive awareness of vaccine value. Vaccine-related knowledge is a significant factor influencing parents’ intentions about their children’s influenza vaccination; this evidence aligns with recent results.Citation34 Furthermore, promotion of policies on vaccination by government is momentous.Citation13 Most guardians who know that the government recommends influenza vaccination annually choose to vaccinate their children in our analysis.Citation35 The relationship between social influence and behavioral intention has also been studied.Citation36 In our study, social influence, including the attitude of family, friends, and HCWs, are seen as determinants of vaccination. Trust in healthcare providers’ advice and mainstream medicine as well as the influence of social norms have been observed to be key factors in vaccine decision-making.Citation32 Groups with high-risk report willingness to follow HCWs’ advice for vaccination and require knowledge of vaccination.Citation37 The lack of vaccine recommendation from HCWs results in parents being less likely to vaccinate their children against influenza, which is in line with previous studies.Citation38–43 Rose supposes that the high-risk perception for influenza vaccines echoes the numerous vaccine controversies – most of which focuses on its safety rather than the reason of the supposed uselessness of this vaccine.Citation44,Citation45 It therefore appears that the likelihood of vaccination for children will increase followed by strengthening HCW vaccine confidence.Citation32

Our data indicate that social influence, relative knowledge, and VH are associated with VB. Our observations also reveal that multiple factors are directly associated with actual vaccine uptake (including VH and social influence) and that some factors (such as related knowledge and social influence) may also concurrently affect VB by influencing VH. In addition, our data indicate that VH is directly affected by the mentioned factors (such as social influence and relative knowledge). The complexity in “achieving from willingness to behavior” among guardians is demonstrated.Citation46 When vaccination is viewed as the social norm, social pressure and responsibility act as a powerful driver of vaccination uptake.Citation39 Positive social influence reduces VH and improves the vaccination rate among guardians. Furthermore, social influence improves related knowledge, which has been evidenced as one of the key elements in the control of pandemics as individuals with high levels of knowledge are more likely to generate protective intentions.Citation47 We find that VB is influenced by both external and internal factors including social influence, relative knowledge, and VH directly or indirectly, which provides the basis for finding more factors and exploring the relationships among them for the low vaccination rate of guardians with low vaccine hesitancy.

In addition to the important insights gained from this study, there are limitations which must be addressed. Firstly, this is a cross-sectional study and the samples are derived from one province in China. Thus, the conclusions for VH may not be accurately generalized to other areas in the country. Secondly, history of influenza vaccination in children is used to describe influenza VB. Even though past behavior is identified as a strong predictor of influenza vaccine acceptance, we cannot be certain whether guardians will vaccinate their children against influenza during the peak of the next influenza season. Furthermore, this survey is conducted in 2019 before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Guardians may change their mind to vaccinate their children due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, vaccine uptake is affected by acceptance, logistical or opportunity-related factors. However, guardians may have changed their minds regarding vaccination, and this consideration is not included in this study.

Conclusions

In this study, we show that cognitions are inconsistent with behaviors regarding influenza vaccination for children, especially among young female guardians, low-income families and parents with low education levels. Moreover, we observe that vaccination is influenced by social influence, relative knowledge, and hesitancy. Our findings suggest that a comprehensive strategy emphasizing the benefits of the influenza vaccine, risk of influenza infection, and ensuring high confidence in vaccines among HCWs help transform willingness into vaccination behavior, thus, leading to children getting vaccinated against the influenza.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alzeer AA, Alfantoukh LA, Theneyan A, Bin Eid F, Almangour TA, Alshememry AK, Alhossan AM. The influence of demographics on influenza vaccine awareness and hesitancy among adults visiting educational hospital in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 2021;29(2):188–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2021.01.001. PMID: 33679179.

- Li L, Liu Y, Wu P, Peng Z, Wang X, Chen T, Wong JYT, Yang J, Bond HS, Wang L, et al. Influenza-associated excess respiratory mortality in China, 2010–15: a population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(9):e473–81. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30163-X. PMID: 31493844.

- World Health Organization. Fact sheet on seasonal influenza. [accessed 2018 Nov 6]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en/.

- Zhao M, Liu H, Qu S, He L, Campy KS. Factors associated with parental acceptance of influenza vaccination for their children: the evidence from four cities of China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(2):457–64. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1771988. PMID: 32614707.

- Lafond KE, Nair H, Rasooly MH, Valente F, Booy R, Rahman M, Kitsutani P, Yu H, Guzman G, Coulibaly D, et al. Global role and burden of influenza in pediatric respiratory hospitalizations, 1982–2012: a systematic analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13(3):1001977. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001977. PMID: 27275597.

- Flu Express. Week 4. Hong Kong: Respiratory Disease Office of the Centre for Health Protection; 2019.

- Wu S, VANA L, Wang L, McDonald SA, Pan Y, Duan W, Zhang L, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Zhang X, et al. Estimated incidence and number of outpatient visits for seasonal influenza in 2015–2016 in Beijing, China. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(16):3334–44. doi:10.1017/S0950268817002369. PMID: 29117874.

- Wei ZSX, Yang Y, Yang Y, Zhan S, Fu C. Seasonal influenza vaccine hesitancy profiles and determinants among Chinese children’s guardians and the elderly. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021 May;20(5):601–10. doi:10.1080/14760584.2021.1908134. PMID: 33792476.

- Xu L, Qin Y, Yang J, Han W, Lei Y, Feng H, Zhu X, Li Y, Yu H, Feng L, et al. Coverage and factors associated with influenza vaccination among kindergarten children 2-7 years old in a low-income city of north-western China (2014-2016). PLoS One. 2017;12(7):0181539. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181539. PMID: 28749980.

- Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger JA. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763–73. doi:10.4161/hv.24657. PMID: 23584253.

- Olson O, Berry C, Kumar N. Addressing parental vaccine hesitancy towards childhood vaccines in the United States: a systematic literature review of communication interventions and strategies. Vaccines Basel. 2020;8(4):590. doi:10.3390/vaccines8040590. PMID: 33049956.

- Bedford H, Attwell K, Danchin M, Marshall H, Corben P, Leask J. Vaccine hesitancy, refusal and access barriers: the need for clarity in terminology. Vaccine. 2018;36(44):6556–58. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.004. PMID: 28830694.

- Turner PJ, Larson H, È D, Fisher A. Drivers and how the allergy community can help. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(10):3568–74. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2021.06.035. PMID: 34242848.

- Chang K, Lee SY. Why do some Korean parents hesitate to vaccinate their children? Epidemiol Health. 2019;41:e2019031. doi:10.4178/epih.e2019031. PMID: 31319656.

- Chung-Delgado K, Valdivia Venero JE, Vu TM. Vaccine hesitancy: characteristics of the refusal of childhood vaccination in a Peruvian population. Cureus. 2021;13(3):e14105. doi:10.7759/cureus.14105. PMID: 33907645.

- Cordina M, Lauri MA, Lauri J. Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination, vaccine hesitancy and intention to take the vaccine. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2021;19(1):2317. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2021.1.2317. PMID: 33828623.

- Gilkey MB, McRee AL, Magnus BE, Reiter PL, Dempsey AF, Brewer NT, Moore AC. Vaccination confidence and parental refusal/delay of early childhood vaccines. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159087. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159087. PMID: 27391098.

- Marshall S, Moore AC, Sahm LJ, Fleming A. Parent attitudes about childhood vaccines: point prevalence survey of vaccine hesitancy in an Irish population. Pharmacy Basel. 2021;9(4):188. doi:10.3390/pharmacy9040188. PMID: 34842830.

- Schmid P, Rauber D, Betsch C, Lidolt G, Denker ML, Cowling BJ. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior – a systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005 – 2016. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170550. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170550. PMID: 28125629.

- Buchan SA, Kwong JC. Trends in influenza vaccine coverage and vaccine hesitancy in Canada, 2006/07 to 2013/14: results from cross-sectional survey data. CMAJ Open. 2016;4(3):E455–62. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20160050. PMID: 27975047.

- Lu X, Lu J, Zhang L, Mei K, Guan B, Lu Y. Gap between willingness and behavior in the vaccination against influenza, pneumonia, and herpes zoster among Chinese aged 50-69 years. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021;20(9):1147–52. doi:10.1080/14760584.2021.1954910. PMID: 34287096.

- Goldman RD, McGregor S, Marneni SR, Katsuta T, Griffiths MA, Hall JE, Seiler M, Klein EJ, Cotanda CP, Gelernter R, et al. Willingness to vaccinate children against influenza after the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Pediatr. 2021;228:87–93 e2. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.08.005. PMID: 32771480.

- Nekrasova E, Stockwell MS, Localio R, Shults J, Wynn C, Shone LP, Berrigan L, Kolff C, Griffith M, Johnson A, et al. Vaccine hesitancy and influenza beliefs among parents of children requiring a second dose of influenza vaccine in a season: an American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Pediatric Research in Office Settings (PROS) study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(5):1070–77. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1707006. PMID: 32017643.

- González-Block MÁ, Gutiérrez-Calderón E, Pelcastre-Villafuerte BE, Arroyo-Laguna J, Comes Y, Crocco P, Fachel-Leal A, Noboa L, Riva-Knauth D, Rodríguez-Zea B, et al. Influenza vaccination hesitancy in five countries of South America. Confidence, complacency and convenience as determinants of immunization rates. PLoS One. 2020 Dec 11;15(12):e0243833. 10.1371/journal.pone.0243833. PMID: 33306744.

- Frawley JE, McManus K, McIntyre E, Seale H, Sullivan E. Uptake of funded influenza vaccines in young Australian children in 2018; parental characteristics, information seeking and attitudes. Vaccine. 2020 Jan 10;38(2):180–86. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.033. Epub 2019 Oct 23. PMID: 31668365.

- Santibanez TA, Nguyen KH, Greby SM, Fisher A, Scanlon P, Bhatt A, Srivastav A, Singleton JA. Parental vaccine hesitancy and childhood influenza vaccination. Pediatrics. 2020;146(6):e2020007609. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-007609. PMID: 33168671x.

- Hong J, Xu XW, Yang J, Zheng J, Dai SM, Zhou J, Zhang QM, Ruan Y, Ling CQ. Knowledge about, attitude and acceptance towards, and predictors of intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine among cancer patients in Eastern China: a cross-sectional survey. J Integr Med. 2022 Jan;20(1):34–44. doi:10.1016/j.joim.2021.10.004. PMID: 34774463.

- Ruggiero KM, Wong J, Sweeney CF, Avola A, Auger A, Macaluso M, Reidy P. Parents’ intentions to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35(5):509–17. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.04.005. PMID: 34217553.

- Wang Q, Xiu S, Zhao S, Wang J, Han Y, Dong S, Huang J, Cui T, Yang L, Shi N, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: COVID-19 and influenza vaccine willingness among parents in Wuxi, China—A cross-sectional study. Vaccines Basel. 2021;9(4):342. doi:10.3390/vaccines9040342. PMID: 33916277.

- Yufika A, Wagner AL, Nawawi Y, Wahyuniati N, Anwar S, Yusri F, Haryanti N, Wijayanti NP, Rizal R, Fitriani D, et al. Parents’ hesitancy towards vaccination in Indonesia: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Vaccine. 2020;38(11):2592–99. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.01.072. PMID: 32019704.

- Ren J, Wagner AL, Zheng A, Sun X, Boulton ML, Huang Z, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. The demographics of vaccine hesitancy in Shanghai, China. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0209117. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0209117. PMID: 30543712.

- Marquez RR, Gosnell ES, Thikkurissy S, Schwartz SB, Cully JL. Caregiver acceptance of an anticipated COVID-19 vaccination. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152(9):730–39. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2021.03.004. PMID: 25483505.

- Ding X, Tian C, Wang H, Wang W, Luo X. Associations between family characteristics and influenza vaccination coverage among children. J Public Health Oxf. 2020;42(3):e199–205. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdz101. PMID: 31553048.

- Shono A, Kondo M. Factors associated with seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among children in Japan. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):72. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-0821-3. PMID: 25886607.

- Wong KK, Cohen AL, Norris SA, Martinson NA, Mollendorf C, Tempia S, Walaza S, Madhi SA, McMorrow ML, Variava E, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices about influenza illness and vaccination: a cross-sectional survey in two South African communities. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2016;10(5):421–28. doi:10.1111/irv.12388. PMID: 26987756.

- Williams SE. What are the factors that contribute to parental vaccine-hesitancy and what can we do about it? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(9):2584–96. doi:10.4161/hv.28596. PMID: 25483505.

- Song Y, Zhang T, Chen L, Yi B, Hao X, Zhou S, Zhang R, Greene C. Increasing seasonal influenza vaccination among high risk groups in China: do community healthcare workers have a role to play? Vaccine. 2017 Jul 24;35(33):4060–63. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.054. PMID: 28668569.

- Newcombe J, Kaur R, Wood N, Seale H, Palasanthiran P, Snelling T. Prevalence and determinants of influenza vaccine coverage at tertiary pediatric hospitals. Vaccine. 2014;32(48):6364–68. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.044. PMID: 24962754.

- Biezen R, Brijnath B, Grando D, Mazza D. Management of respiratory tract infections in young children-A qualitative study of primary care providers’ perspectives. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):15. doi:10.1038/s41533-017-0018-x. PMID: 28258279.

- Tuckerman J, Misan S, Salih S, Joseph Xavier B, Crawford NW, Lynch J, Marshall HS. Influenza vaccination: uptake and associations in a cross-sectional study of children with special risk medical conditions. Vaccine. 2018;36(52):8138–47. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.09.039. PMID: 30454947.

- Abdullahi LH, Kagina BM, Ndze VN, Hussey GD, Wiysonge CS. Improving vaccination uptake among adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;1(1):CD011895. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011895.pub2. PMID: 31978259.

- Lin CJ, Nowalk MP, Zimmerman RK, Ko F-S, Zoffel L, Hoberman A, Kearney DH. Beliefs and attitudes about influenza immunization among parents of children with chronic medical conditions over a two-year period. J Urban Health. 2006;83(5):874–83. doi:10.1007/s11524-006-9084-z. PMID: 16770701.

- Zakhour R, Tamim H, Faytrouni F, Khoury J, Makki M, Charafeddine L, Alameddine M. Knowledge, attitude and practice of influenza vaccination among Lebanese parents: a cross-sectional survey from a developing country. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258258. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258258. PMID: 34648535.

- Wilson R, Zaytseva A, Bocquier A, Nokri A, Fressard L, Chamboredon P, Carbonaro C, Bernardi S, Dubé E, Verger P. Vaccine hesitancy and self-vaccination behaviors among nurses in southeastern France. Vaccine. 2020 Jan 29;38(5):1144–51. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.11.018. PMID: 31810781.

- Di Martino G, Di Giovanni P, Di Girolamo A, Scampoli P, Cedrone F, D’Addezio M, Meo F, Romano F, Di Sciascio MB, Staniscia T. Knowledge and attitude towards vaccination among healthcare workers: a multicenter cross-sectional study in a Southern Italian region. Vaccines Basel. 2020 May 24;8(2):248. 10.3390/vaccines8020248. PMID: 32456273.

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DM, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007-2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150–59. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081. PMID: 24598724.

- Elhadi M, Msherghi A, Alsoufi A, Buzreg A, Bouhuwaish A, Khaled A, Alhadi A, Alameen H, Biala M, Elgherwi A, et al. Knowledge, preventive behavior and risk perception regarding COVID-19: a self-reported study on college students. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(Suppl 2):75. doi:10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.23586. PMID: 33623599.