?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Vaccines are not free from adverse outcomes. However, the evidence of adverse outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination among health-care professionals (HCPs) in the study setting was scanty. Aimed to assess outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors among health-care professionals in Oromia region, Ethiopia. An online cross-sectional survey was conducted from 1 October to 30 October 2021. Data were collected using questionnaire created on Google forms. A snowball sampling technique through the authors’ network on the popular social media was used. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 25. The Adjusted Odd Ratio (AOR) along with the 95% confidence level and variables with a p value <.05 were considered to declare the statistical significance. About 93.9% of the participants had experienced mild-to-moderate adverse outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination. Being married [AOR = 4.19, 95% CI:2.07,8.45] ,family size >5 [AOR = 5.17, 95% CI: 1.74, 15.34], family not tested for COVID-19 [AOR = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.15,0.97], lack of family support to take the vaccine [AOR = 3.58, 95% CI: 1.75, 7.33], heard anything bad about the vaccine [AOR = 4.17, 95% CI: 1.90,9.13] and very concerned as the vaccine could cause Adverse Events Following Immunization (AEFI) [AOR = 6.24, 95% CI: 1.96,19.86] were statistically associated with the outcome. The study showed that over nine out-of-often participants had experienced mild-to-moderate adverse outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination. However, severe adverse outcome experienced was very low, which could not hinder to take the vaccine due to fear of its side effects. Marital status, family size, family tested for COVID-19, lack of family support to take the vaccine, hearing anything bad about the vaccine, and being concerned about as the vaccine could cause adverse events were factors associated with the outcome.

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by a newly discovered coronavirus, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).Citation1,Citation2 World Health Organization (WHO) declared it as a global pandemicCitation3,Citation4 on 12 March 2020 and the first confirmed case was reported in Ethiopia on March 13, 2020.Citation5 So, nowadays we are living in a pandemic situation given its rapid spread and the occurrence of new variants.Citation6,Citation7 To prevent this pandemic and related consequence, various risk mitigation measures were implemented to halt its spread and reduce the negative health, social, economic impact of the pandemic across every corner of the world, including Ethiopia.Citation8–10

Vaccination is an effective way of combating infectious conditions and is particularly essential for controlling this pandemic.Citation11 Hence, hundreds of candidate vaccines have been tested and deployed for use all over the world.Citation12,Citation13 Based on this, the Ethiopian health minister launched the COVID-19 vaccine on the 13th of March 2021 and the first candidates to receive this vaccine were population groups with a relatively higher risk of contracting the virus.Citation12,Citation14 However, due to the inadequate supply of vaccines globally, governments have prioritized high-risk groups to receive the initial supply of vaccines. Those high-risk groups include healthcare workers; older people, especially those with chronic co-morbid conditions; and those in essential services.Citation15 Healthcare professionals are at a high risk of contracting the COVID-19 disease due to their direct or indirect contact with exposed clients or patients.Citation16,Citation17

As of January 27, 2022, about 61.1% of the world population had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. But, only 10% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose.Citation18 Ethiopia, as of January 27, 2022, about 2.7 million of the 3.7 million people who received their first vaccination have been fully vaccinated and the types of vaccines administered were AstraZeneca, Johnson and Johnson/Janssen, Sinopharm, and Pfizer-BioNTech.Citation19

However, vaccines are not free from side effects, or “adverse effects,” but some adverse events may be due to coincidence and are not caused by the vaccine.Citation20 Also, false information and miss-trusts have been contributed to the growing anxiety and vaccine hesitancy associated with a fear of the occurrence of long-term adverse events.Citation21 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other studies; symptoms at the injection site (swelling, pain, and redness) as well as systemic effects (back pain, tiredness, headache, muscle pain, joint pain, chills, fever, and nausea) are listed as reactions due to COVID-19 vaccines.Citation22–24 So, following its utilization, post-market adverse events and various safety-related studies have been conducted across different countries by different scholars regarding AEFI from different angles.Citation8 Of these, AEFI was reported in Afghanistan as, 93.5%;Citation25 Korea, 90%;Citation26 Togo, 71.5%;Citation10 South India, 58%Citation27 and Indonesia, 38.5%,Citation28 in Ethiopia’s two regions, Amhara and Tigray, studies focusing on AstraZeneca have also been reported.Citation8,Citation12

To the knowledge of the authors, no prior studies have been conducted on the AEFI of COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors among healthcare professionals in Oromia region, Ethiopia. Also, studies that have been conducted elsewhere mostly focus on specific vaccines, full dosages, and various views or perspectives from the current study. Therefore, to fill these gaps, this study aimed to assess outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination and identify associated factors among healthcare professionals in the study setting.

Methods and materials

Study setting, design, and period

An online cross-sectional E-survey was conducted among healthcare professionals (HCPs) working across different health institutions in the Oromia region, Ethiopia from 1 October to 30 October 2021.

Population and eligibility criteria

All employed healthcare professionals and selected HCPs working in the health institutions were the source and study population, respectively. Employed HCPs aged 18 and up who live in the region, can read and understand English, and agreed to participate and complete the survey were included in the analysis. Whereas, who could not access the Internet to use Facebook, e-mail, and telegram services were excluded. Also, incomplete responses were excluded from the analysis.

Sample size and technique

The sample size was initially determined using a single population proportion formula by considering the following assumptions: where the proportion of AEFI among HCPs was taken as 50% (as there was no previous study in Ethiopia at the time). By considering 5% margins of error and a 10% potential non-response rate, the sample size became 423.

Where:

n = is the desirable calculated sample size

Z α/2 = Standard normal variable at 95% confidence level (1.96)

P = the proportion of AEFI (50%).

d = margin of error (5%)

Therefore, the sample size “n” was calculated as:

Since the data was collected online, about 602 participants responded in a given period. However, after considering the eligibility criteria and excluding incomplete data, 522 HCPs were included in the final analysis. The study participants were selected using snowball sampling techniques through the author’s network using the most popular social media like Facebook, Telegram, and also e-mails.

Study variables and measurements

The dependent variable was outcomes following immunization of COVID-19 vaccination. The socio-demographic and economic (age, sex, religion, ethnicity, residence, marital status, educational status, family size, and monthly income); profession and work area (place of work or types of facility, types of profession); health status and exposure (perceived own health status, perceived family health status, tested for COVID-19, history of chronic illness, history of vaccination for other diseases, and contact history with COVID-19 patients or clients) and vaccine-related factors were the independent variables considered.

Basically, two major questions were asked: First, “Have you taken the COVID-19 vaccine at least one dose as of today?” This question was answered as either a “Yes or No” type close-ended question to know the vaccination status. Second, if you have been vaccinated against any types of COVID-19 vaccines at least once, have you experienced any adverse outcomes were asked to report any reactions they might have suffered after receiving the vaccine immediately? This question was also answered as either a “Yes or No” type closed-ended question to know the occurrence of AEFI. Based on this, Yes for any adverse outcomes and No for no adverse outcomes. Then, they were asked about a list of adverse outcomes that they may have experienced if they said yes, such as; headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, cough, chills, fatigue, joint pain, back pain, throat pain, abdominal pain, diarrhea, pain at vaccination sites, redness at the vaccination site, sleeping disorder, skin rash and etc. they had experienced immediately within 48 h of COVID-19 vaccination. Also, as the study participants were health professionals, they themselves could determine the presence or absence of AEs and they could have also reported if they had been diagnosed by senior health professionals working on health facilities.

Operational definitions

Adverse outcomes following immunization

Any unfavorable medical occurrence that occurs immediately or with in a short-term (48 h) after immunization and does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the use of the vaccine and coupling events or other events. Those respondents who had experienced any AEFI immediately answered “Yes” and those who had not experienced AEFI immediately answered “No.” They are very common, common, uncommon, and very rare adverse events or reactions reported by respondents following COVID-19 vaccine immunization, which were classified as mild, moderate, or severe. A serious AEFI is one that results in hospitalization or a prolongation of hospitalization, permanent disability or incapacity, or death. Non-serious AEFI is defined as an event that does not pose a potential risk to the recipient’s health and can range from mild-to-moderate symptoms, which did not affect daily activities. Mild; when it did not totally affect daily activities,whereas moderate when it partially affect daily activities.Citation29

Data collection and procedures

An online platform was utilized to collect data using a semi-structured self-administered questionnaire. It was adapted by reviewing different literates.Citation30 The questionnaire was comprised of four main sections, namely, socio-demographic and socio-economic; profession and work area; health status and exposure; and Vaccine-related factors. The tool has a brief introduction to the study’s background, objective of the study, eligibility criteria, and voluntary nature of participation; a declaration of confidentiality and anonymity; and informed consent of each participant, asking whether or not they want to participate in the study. The link to the questionnaire was sent to the authors through the most popular social media platforms such as Facebook, Telegram, and e-mail during data collection. Before beginning the survey, the respondents’ responses, as well as the terms and conditions of Google forms, were verified.

Data quality assurance

Different measures were undertaken to maintain the quality of the data before, during, and after data collection. The questionnaire prepared in English was translated into the Afan Oromo language and then translated back into English, and the contents of the questionnaires were checked for consistency before the actual data collection. Additionally, pretesting of the questionnaire was conducted on some of the HCPs surrounding us, and then, after feedback had been received from those participants, necessary modifications and corrections were made accordingly to the questionnaire before distributing the link. The exclusion of incomplete responses was also done for the final analysis.

Data analysis procedure

Completed questionnaires were extracted from Google Forms and exported to Microsoft Excel 2013 for coding and then exported to SPSS version 25 for data analysis. Data analysis was performed using a variety of descriptive statistics such as frequency distribution and percentage. Variables with a p ≤ .25 on binary logistic regression analysis were considered as candidates for multivariable logistic regression analysis. A backward (LR) variable selection method was used in multivariable logistic regression. Independent variables with p-values <.05 and Adjusted Odds Ratio at 95% CI were used to declare the predictors of the outcome variable. Finally, the goodness of model fitness was assessed using the Hosmer and Lemeshow test, which indicated that the model was appropriate for data analysis at p-value > .05.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

A total of 522 participants were involved in the study. The mean age of the participants was 30.9 ± 4.75, with more than three-quarters (406) (77.8%) of them being within the age range of 25 to 34 years old. The majority of the participants were males, 471 (90.2%); Oromo, 321 (61.5%); protestant, 168 (32.2%); and married, 351 (67.2%). In this study, both bachelors and master’s degree holders together accounted for 80.8%. Also, about 85.8% of the respondents reside in urban areas, and 13.8% of them have five or more children per household ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of the participants on the study outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination among health-care professionals in Ethiopia, 2021 (N = 522).

About 183 (35.1%), 160 (30.7%), 153 (29.3%), 23 (4.4%), and 3 (0.6%) of these were clinicians, academicians, health office staff, academicians working in university hospitals or colleges, and other staff. According to the work area distribution, 152 (29.1%), 114 (21.8%), 112 (21.5%), and 100 (19.2%) of them work in universities or colleges (academicians), hospitals, health centers, and health offices, respectively. Profession-wide, most of the participants were public health, with 258 (49.4%), and nurses, with 124 (23.8%).

Regarding health status and exposure-related characteristics, 117 (22.4%) of the respondents’ family members (at least one member) had been tested for COVID-19, of which 60 (24.7%) of them had taken the vaccine. Almost 48 (9.2%) of the respondents had major chronic diseases. Nearly half (249, 47.7%) of the respondents had children less than five years old, of which 213 (85.5%) of them had been vaccinated for other diseases before.

About 248 (47.1%) of the respondents had taken care of confirmed COVID-19 patients. Of these, 125 (23.9%) and 123 (23.6%) had direct and no direct contact with them, respectively. About 199 (38.1%) of respondents perceived that they were at risk of getting COVID-19 disease.

Outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination

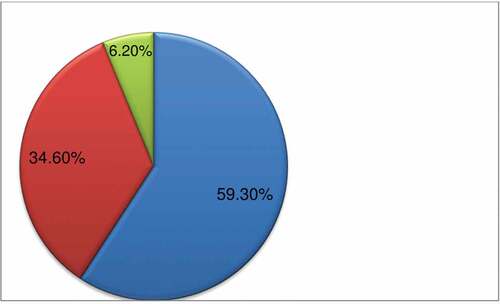

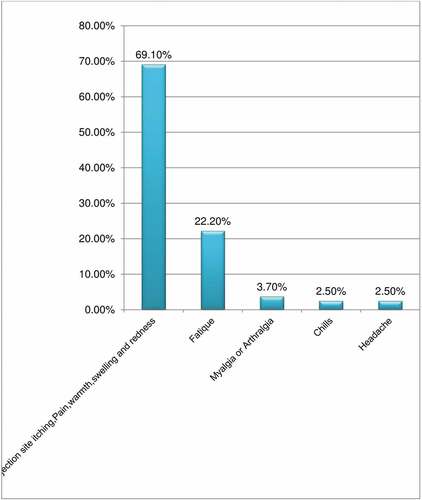

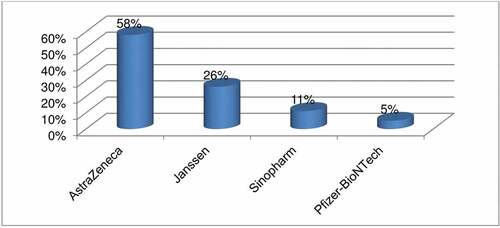

The study showed that of those respondents who had taken the vaccine, about 243(75%) (68.2–79.7%) of them had experienced AEFI of COVID-19 vaccination (). Regarding their perceived severity of those adverse outcomes 144 (59.3%), 84 (34.6%), and 15 (6.2%) of the respondents had experienced mild, moderate, and severe infections, respectively (). As it was indicated on , the most predominant adverse events reported following immunization was mostly associated with the injection site (itching, warmth, pain, swelling, and tenderness) (69.1%) followed by fatigue (22.2%). The predominant type of vaccine received was Astrazenica vaccine, which was accounted as 58% ().

Figure 1. Outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare professionals in Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2021 (N = 324).

Figure 2. COVID-19 vaccine associated SEs or AEs following immunization among healthcare professionals in Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2021.

Figure 3. Types of COVID-19 Vaccines received among healthcare professionals in Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2021.

Table 2. Factors associated with outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination among health-care professionals in Ethiopia, 2021 (N = 324).

Factors associated with outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination

Variables such as; age, marital status, educational status, family size, monthly income, types of profession, expertise or staffing, family tested for COVID-19, presence of chronic disease, having children <5 year, ever taken care (previous contact) of the confirmed COVID-19 patients/clients, risk of getting COVID-19 disease, peer support to take the vaccine, family support to take the vaccine, heard any things bad about the vaccine and concerned about the vaccine could cause adverse events were statistically associated with outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination on binary logistic regression analysis ().

After controlling for possible confounders, variables such as marital status, family size, family tested for COVID-19, family support to take the vaccine, hearing anything bad about the vaccine, and being concerned about as the vaccine could cause adverse events were statistically associated with outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination in multivariable logistic regression analysis ().

The study implies that married respondents were 4 times more likely to experience AEFI of COVID-19 vaccination [AOR = 4.19, 95% CI: 2.07, 8.45] than their counterparts. The odds of experiencing AEFI after COVID-19 vaccination were 5.17 times higher among respondents with a family size greater than five [AOR = 5.17, 95% CI: 1.74, 15.34] than among respondents with a family size of less than five.

The probability of experiencing AEFI of COVID-19 vaccination among HCPs whose families were not tested for COVID-19 was reduced by 61% [AOR = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.15, 0.97] as compared to their counterparts.

Respondents who did not have family support to take the vaccine were 3.58 times more likely to experience AEFI of COVID-19 vaccination [AOR = 3.58, 95% CI: 1.75, 7.33] than those who had family support. Also, the odds of experiencing AEFI of COVID-19 vaccination were 4.17 times higher among respondents who had heard anything bad about the vaccines [AOR = 4.17, 95% CI: 1.90, 9.13] than their counterparts. Lastly, the probability of experiencing AEFI after COVID-19 vaccination was 6 times higher [AOR = 6.24, 95% CI: 1.96, 19.86] among respondents who were very concerned that the vaccine could cause AEFI compared to those who were not at all concerned about it ().

Discussion

This study assessed AEFI of COVID-19 vaccination and it revealed that three-fourths of the participants had experienced the AEs. This finding was greater than study done in Tigray region of Ethiopia, 63.8%; South India, 58% and Indonesia, 38%.Citation8,Citation27,Citation28 The discrepancy might be due to vaccine on which the AEFI was assessed, time period considered for data collection and socio-cultural differences as a result of differences in geographic area. The current study considered any vaccine, whereas previous studies focused on highly specific vaccines.

However, it was lower than the study conducted in other countries, such as Afghanistan, 93.5%Citation25 and Korea, 90%.Citation26 The probable reason for this discrepancy might be due to difference in study population as medical students might have experienced an adverse event more than employed and experienced healthcare professional staff due to medical student syndrome. Also, it was in line with the study conducted in UK, 71.9%Citation20 and one of the low- and middle-income countries,Citation12 which revealed that AEFI of COVID-19 vaccination was reported as 75.8%. Additionally, the most important finding revealed by this study was that, almost 94% of the outcomes experienced were mild-to-moderate infection which can enable any one to take the vaccine without any rumors as this indicated as it also had no negative externalities associated with the vaccine intake.

Marital status, family size, family tested for COVID-19, having family support to take the vaccine, heard any things bad about the vaccine and concerned about as the vaccine could cause adverse events were variables associated with outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination. This showed that the probability of developing AEFI of COVID-19 vaccination was experienced among married respondents by four folds more than their counterparts. This finding was supported by a study done in Togo,Citation10 where over 50% of married respondents were prone to AEFI of COVID-19 vaccination and perceptions about serious and life-threatening side effects have been reported in the study. Also, the finding was in line with studies done in Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Tigray region, EthiopiaCitation8 and Southern EthiopiaCitation30 in which almost half of the study participants had experienced AEFI in both studies. This could be due to similarity in population characteristics, the health system under which they have been governed, and also that married individuals might have a higher risk perception than unmarried ones because they can think more about their families as they might have at least two or more families.

Respondents with a family size of more than 5 were five times more likely than their counterparts to experience AEFI after COVID-19 vaccination. This finding was a unique finding from studies conducted elsewhere and could be due to the fact that an individual with a higher family member might have a higher risk perception than their counterpart. Also, studies supported thatCitation31 having more children increases the probability of getting COVID vaccine. This could be due to the fact that, those respondents who had more child had greatest fear for being affected by COVID-19 due to higher confinement in one house and overcrowding and this in turn could result in the higher chance of experiencing adverse reactions and there might be greater probability of encountering history of sub-clinical infections.

The probability of experiencing AEFI was reduced by 61% among healthcare professionals whose families were not tested for COVID-19. This finding was supported by the study conducted in Ghana,Citation16 which showed that about 83.8% had reported that no member in their households had been diagnosed with COVID-19 and a higher proportion of those whose household member (s) had been diagnosed with COVID-19, 57.9% indicated acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccines. This indicates that the more the household members were not tested for the disease, the lower the acceptance of the vaccine, which in turn indicates the less likelihood of experiencing adverse events. This could be in turn explained as the study subjects might have a higher frequency of having a history of subclinical COVID-19 infection as they are higher risk group that could urge them to be tested for the disease, because of fear of the disease due to there might be repeated contact with the COVID-19 clients or patients in the health facilities and the experiences of vaccine AEs was more likely happen in such population groups.

Regarding family support to take the vaccine, respondents who did not have family support to take the vaccine were almost four times more likely to experience the events than those who had family support. This finding was supported by studies done in other countries.Citation12,Citation30 This could be due to fear of signs and symptoms associated with the vaccine they had misinformed without any scientific evidence.

The findings also revealed that the odds of experiencing AEFI of COVID-19 vaccination were higher among respondents who had heard anything bad about the vaccines. This result was in line with different studies that have been conducted on different aspects and perspectives of the vaccines. Of these, studies were done in GhanaCitation16 and in other countries.Citation12,Citation30 This is supported by an insight given by one of the surveys conducted,Citation32 where people who were exposed to negative information about the vaccine from the media reported more adverse events, thereby increasing people’s concerns.

Finally, the study showed that the probability of experiencing adverse events following immunization was six times higher among respondents who were very concerned that the vaccine could cause AEFI. This is in line with a study done in Ghana,Citation16 Togo,Citation10 low- and middle-income countriesCitation33 and the Amhara region of Ethiopia.Citation34 Concerns about side effects are the most common reasons for hesitancy reported in these studies. This is because hesitancy is mostly driven by concerns about vaccine safety, efficacy, and side effects. These are also the major reasons for COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among HCWs globally.

The study had limitations. One was the cross-sectional nature of the study, as it could not show a cause and effect relationship. Two, this study used non-probability sampling techniques, such as snowball, which could be difficult to generalize to the whole healthcare professionals. Three, health professionals who had no access to internet services could not participate in this study. Four, an online survey could lead to a low response rate. Five; there might be the probability for the occurrence of coincidental events that are not due to the vaccine or immunization process but are temporally associated with immunization within a time period that might result in over estimation for the occurrences of an event. Despite this, the findings of this study will be used as evidence and input for HCPs, decision makers, policy designers, implementers, and managers of health service organizations at different levels to convince anyone of rumors regarding the misinformation about vaccine adverse events disseminated in the community at this critical time when health systems across the globe are being challenged due to this pandemic.

Conclusion and recommendation

The study showed that over nine out of ten participants had experienced mild-to-moderate adverse outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination. However, the severe adverse outcome experienced was very low, which could not hinder to take the vaccine due to fear of its side effects. Marital status, family size, family tested for COVID-19, having family support to take the vaccine, hearing anything bad about the vaccine, and concern about as the vaccine could cause adverse events were factors associated with outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination.

Hence, health managers at different levels of the health system should enhance full vaccination of any HCPs as this might have no negative externality. The authors also encourage all the eligible populations to receive the COVID-19 vaccine as the benefits of vaccination outweigh the risk of any adverse events. Finally, further studies will be recommended to assess the long-term side effects and provider-side costs associated with the vaccination.

Authors contribution

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical approval

This clinical research was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Wallaga University, Institute of Health Sciences (Reference number: IRB/298/2021). It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The questionnaire was designed to be anonymous, and the result did not identify the personalities of the respondents; rather it was presented as aggregated statistics. The data was kept in a protected and safe location.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all the study participants and Wallaga University for their due cooperation and involvement during the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

All the data supporting the study’s findings are within the manuscript. Additional detailed information and raw data will be shared upon request addressed to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017.

- Sim MR. The COVID-19 pandemic. Major risks to healthcare and other workers on the front line. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77(5):281–82. doi:10.1136/oemed-2020-106567.

- Eurosurveillance Editorial Team. Note from the editors. World Health Organization declares novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) sixth public health emergency of international concern. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(5):2019–20. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.200131e.

- Ndwandwe D, Wiysonge CS. COVID-19 vaccines:safety surveillance manual. Curr Opin Immunol. 2021;71:111–16. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2021.07.003.

- University JH. COVID-19 data in motion: Internet. 2021 Oct 5.

- Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu Y, Mao Y-P, Ye R-X, Wang Q-Z, Sun C, Sylvia S, Rozelle S, Raat H. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of COVID during the early outbreak period. Infect Dis Poverty [Internet]. 2020;9(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x%0A(2020).

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 weekly epidemiological update. World Health Org [Internet]. 2022;Edition 73(Jan):1–23. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-weekly-epidemiological-update.

- Tequare MH, Abraha HE, Adhana MT, Tekle TH, Belayneh EK, Gebresilassie KB, Wolderufael AL, Ebrahim MM, Tadele BA, Berhe DF. Adverse events of Oxford/AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine among health care workers of Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Tigray, Ethiopia. IJID Reg [Internet]. 2021;1(Aug):124–29. doi:10.1016/j.ijregi.2021.10.013.

- World Health Organization. Overview of public health and social measures in the context of COVID-19. World Health Org. 2020;2020(May):1–8.

- Konu YR, Gbeasor-Komlanvi FA, Yerima M, Sadio AJ, Tchankoni MK, Zida-Compaore WIC, Nayo-Apetsianyi J, Afanvi KA, Agoro S, Salou M. Prevalence of severe adverse events among health professionals after receiving the first dose of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 coronavirus vaccine (Covishield) in Togo, March 2021. Arch Public Heal [Internet]. 2021;79(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s13690-021-00741-x.

- Manning ML, Gerolamo AM, Marino MA, Hanson-Zalot ME, Pogorzelska-Maziarz M. Factors influencing adverse events following immunization with AZD1222 in Vietnamese adults during first half of 2021. Nuseing Outlook [Internet]. 2021;69(Jan):565–73. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2021.01.019.

- Solomon Y, Eshete T, Mekasha B, Assefa W. Covid-19 vaccine: side effects after the first dose of the oxford astrazeneca vaccine among health professionals in low-income country: Ethiopia. J Multidiscip Healthc [Internet]. 2021;14:2577–85. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S331140.

- Onyeaka H, Al-Sharify ZT, Ghadhban MY, Al-Najjar SZ. A review on the advancements in the development of vaccines to combat coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Exp Vaccine Res [Internet]. 2021;10(1):6–12. doi:10.7774/cevr.2021.10.1.6.

- Organization WH. Ethiopia introduces COVID-19 vaccine in a national launching ceremony [Internet]. 2021. https://www.afro.who.int/news/ethiopia-introduces-covid-19-vaccine-national-launching-ceremony.

- Kaur SP, Gupta V. COVID-19 Vaccine: a comprehensive status report. Virus Res [Internet]. 2020;288(Jan):13. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198114.

- Khalis M, Hatim A, Elmouden L, Diakite M, Marfak A, Ait El Haj S, Farah R, Jidar M, Conde KK, Hassouni K. Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination among health care workers: a cross-sectional survey in Morocco. Hum Vaccines Immunother [Internet]. 2021;17(12):5076–81. doi:10.1155/2021/9998176%0AResearch.

- Chou R, Dana T, Buckley DI, Selph S, Fu R, Totten AM. Epidemiology of and risk factors for coronavirus infection in health care workers; A living rapid review. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2020;173(2):120–36. doi:10.7326/M20-1632.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations. WHO [Internet]. 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

- World Health Organization. Ethiopia-WHO coronavirus(COVID-19) dashboard [Internet]. 2022. https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/et.

- National Academy of Sciences. Adverse effects of vaccines :evidence and causality. Inpharma Wkly [Internet]. 2011;1030:21. www.iom.edu/vaccineadverseeffects.

- Scheel DP. Oxford–astrazeneca COVID-19 vaccine efficacy published. Ann Oncol [Internet]. 2020;20(Jan):19–20. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32623-4.

- Andrzejczak-Grządko S, Czudy Z, Donderska M. Side effects after COVID-19 vaccinations among residents of Poland. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(12):4418–21. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202106_26153.

- Klugar M, Riad A, Mekhemar M, Conrad J, Buchbender M, Howaldt H-P, Attia S. Side effects of mrna-based and viral vector-based COVID-19 vaccines among German healthcare workers. Biology (Basel) [Internet]. 2021;10(8):1–21. https://www.mdpi.com/journal/biology.

- Riad A, Pokorná A, Mekhemar M, Conrad J, Klugarová J, Koščík M, Klugar M, Attia S. Safety of chadox1 ncov-19 vaccine: independent evidence from two EU states. Vaccines. 2021;9(6):1–12. doi:10.3390/vaccines9060673.

- Azimi M, Dehzad WM, Atiq MA, Bahain B, Asady A. Adverse effects of the COVID-19 vaccine reported by lecturers and staff of Kabul University of Medical Sciences, Kabul, Afghanistan. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:4077–83. doi:10.2147/IDR.S332354.

- Jeon M, Kim J, Oh CE, Lee J-Y. Adverse events following immunization associated with coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination reported in the mobile vaccine adverse events reporting system. J Korean Med Sci [Internet]. 2021;36(17):1–8. doi:10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e114.

- Basavaraja CK, Sebastian J, Ravi MD, John SB. Adverse events following COVID-19 vaccination: first 90 days of experience from a tertiary care teaching hospital in South India. Ther Adv Vaccines Immunother [Internet]. 2021;9(2020 Mar):1–12. doi:10.1177/25151355211055833.

- Supangat S, Sakinah EN, Nugraha MY, Qodar TS, Mulyono BW, Tohari AI. COVID-19 vaccines programs: Adverse Events Following Immunization (AEFI) among medical clerkship students in Jember, Indonesia. Digit Repos Univ Jember. 2021;22(1):58. doi:10.1186/s40360-021-00528-4.

- Abarca RM. Global manual on surveillance of adverse events following immunizaion. WHO. Nuevos Sist Comun e Inf. 2021:2013–15.

- Zewude B, Habtegiorgis T, Hizkeal A, Dela T, Siraw G. Perceptions and experiences of COVID-19 vaccine side-effects among healthcare workers in Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Pragmatic Obs Res [Internet]. 2021;12:131–45. doi:10.2147/POR.S344848.

- Eric B, Elizaveta P. Family size and vaccination among older individuals: the case of COVID-19 vaccine. SHARE ERIC. 2021. doi:10.17617/2.3361025.

- Rief W. Fear of Adverse Effects and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: recommendations of the Treatment Expectation Expert Group. JAMA Heal Forum [Internet]. 2021 Mar 6;2(4):e210804. https://jamanetwork.com/on.

- Machingaidze S, Wiysonge CS. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Nat Med [Internet]. 2021;27(8):1338–39. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01459-7.

- Aemro A, Amare NS, Shetie B, Chekol B, Wassie M. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care workers in Amhara region referral hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Epidemiol Infect [Internet]. 2021;149(e225):1–8. doi:10.1017/S0950268821002259.