ABSTRACT

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is a highly contagious sexually transmitted infection that leads to preventable cancers of the mouth, throat, cervix, and genitalia. Despite the wide availability of HPV Vaccine (HPVV) in Canada, its uptake remains suboptimal. This review aims to identify factors (barriers and facilitators) in HPV vaccine uptake across English Canada at three levels (provider, system, and patient). We explored academic and gray literature to examine factors involved in HPVV uptake and synthesized results based on interpretive content analysis. The review identified the following factors of prime significance in the uptake of the HPV vaccine (a) at the provider level, ‘acceptability’ of the HPV vaccine, and ‘appropriateness’ of an intervention (b) at the patient level, the ‘ability to perceive’ and ‘knowledge sufficiency’ (c) at the system level, ‘attitudes’ of different players in vaccine programming, planning and delivery. Further research is needed to conduct population health intervention research in this area.

Introduction

The verb “eradicate” has never been used in the context of cancer before, and to “eradicate” Human Papillomavirus (HPV) related cancers (cervical, oral, and genital), preventive strategies should target optimal uptake of HPV immunization in all jurisdictions of Canada.Citation1 Canada has been a success story in implementing a publicly funded school-based HPV immunization program.Citation1 Canada’s earlier achievements are challenged by the negative influence of the rapidly prevailing anti-vaccine activism, hence reversing the earlier gains.Citation2 Therefore, despite a widespread effort to gain optimal uptake of publicly funded Human Papilloma Virus Vaccine (HPVV) programs throughout Canada, the uptake of HPVV remains suboptimal in some Canadian jurisdictions.Citation3 The COVID-19 pandemic has further affected cancer control efforts across the spectrum.Citation4 International efforts highlighted that the diagnoses of cancers were reduced by 40% between March 9 and May 17, 2020.Citation5 Moreover, the program interruptions will notably impact future cancer survival.Citation4 Information on the determinants of HPVV uptake is vital for health policymakers to develop strategies that enhance the uptake of widely available HPVV and meet the target the Government of Canada has set of reaching 90% HPVV coverage among Canadian adolescents by 2025.Citation6

Human papillomavirus is the most common viral infection of the reproductive tract and is the leading cause (more than 95%) of cervical cancer.Citation7 All sexually active women and men contract at least one of its types at some point in life.Citation8 According to the Canadian Cancer Society, HPV is more common than any other sexually transmitted infection combined.Citation9 Most will never know if they have been infected because HPV often does not cause any symptoms, making it hard to know exactly when or how the virus was spread.Citation9 Lung cancer has a high incidence but low survival; therefore, its prevalence is lower because fewer survivors remain in the population over time.Citation4 In contrast, cervical cancer falls into the top 10 cancer types for the 25-year prevalence due to its high survival and the younger average age at diagnosis.Citation4 The projections by the Oncosims model indicate that increasing HPVV uptake to 90% from 67% would result in a 23% reduction in cervical cancer incidence rates, which in turn causes a 23% decline in the average annual cervical cancer mortality rate.Citation6 Vaccination against HPV is a cornerstone in preventing HPV-related infections and cancers developed as a sequela.Citation10

Despite this widespread effort, HPVV uptake has remained suboptimal in certain Canadian jurisdictions.Citation3 The rate of cervical cancer among Canadian women has not declined since 2005.Citation11 The suboptimal uptake of HPVV with a status quo of cervical cancer incidence rate is partly because HPV immunization’s impact on cancer prevention has not been realized adequatelyCitation1 by vaccine providers and vaccine receivers.Citation12 This is further challenged by the presence of a significant portion of women who remained under-screened or unscreened for detection of cancerous changes via pap smearCitation13 The disease’s infectious nature, its widespread transmission, and the consequent development of cancer of a preventable origin have become common knowledge among scientists and public health professionals. Further exploration of determinants of HPVV uptake (barriers and facilitators) is required to situate contextually appropriate policies around enhancing its uptake. It should be realized that HPV is the most common Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) that causes cancers of preventable nature. Thus, primary prevention of HPV by vaccination should be a high priority in Canada’s cancer prevention efforts. Clearly, a thorough examination of determinants of HPVV uptake across English Canada is an important topic, although literature on this topic is sparse.

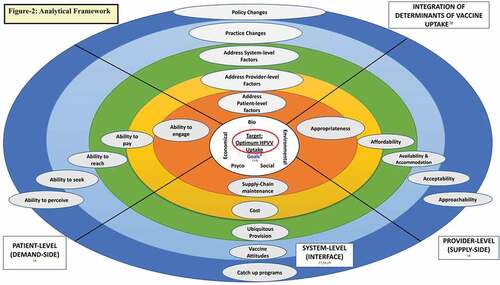

This review brings together literature that articulates barriers and facilitators in HPVV uptake by meaningfully integrating determinants of vaccine uptake on both the demand and supply sides to balance the health-care equation and ultimately lead to enhanced HPVV utilization (refer to Figure −2: Analytical Framework). Extrapolating on Engel’s biopsychosocial concept model,Citation14 we classify the identified barriers and facilitators at three levels: provider, patient, and system level to illuminate the factors adherent to HPVV uptake distinctively on either side of the health-care equation (the supply vs demand side).Citation15 Using several 10 A’s themes from Levesque’s conceptual framework,Citation16 the provider-level determinants (of vaccine uptake) include appropriateness, affordability, availability, acceptability, and approachability.Citation16 The patient-level determinants include the ability to engage, ability to pay, ability to reach, ability to seek, and ability to perceive. The system-level determinants include ubiquitous Provision,Citation17 catch-up Programs,Citation18 supply-Chain maintenance, cost, and vaccine Attitudes.Citation19 We connect the identified factors with a set of vaccine uptake determinantsCitation20 to uncover high-resolution quality improvement investment targets for under-immunized population groups.

Methods

A systematic approach was implemented to review studies of barriers and facilitators affecting HPVV uptake across English Canada.

Search strategy

We undertook an extensive and systematic review of the literature using the following electronic databases: Medline, PubMed, SCOPUS, and Web of Sciences. We developed and conducted searches in consultation with an academic librarian using various combinations of keywords and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms using the search strategy worksheet by the University of Ottawa.Citation21

Broadly, the selection criteria for studies included any study that identifies barriers and facilitators in HPVV uptake involving individuals eligible for and receiving the HPV vaccine. We assessed the studies for the following outcomes: 1) If the study discussed factors around decreased uptake of HPVV (barriers) and/or 2) If the study examined factors around increased uptake of vaccine (facilitators and interventions).

We conducted a search after creating the search syntaxes. Search syntaxes individual to each database and a master list of keywords prepared and utilized for academic literature search are included in the appendix. We searched the gray literature in two steps. A general search utilizing Google Scholar was followed by a specific search using websites of relevance and interest: Urban Public Health Network (UPHN) and Ontario Public Health Libraries Association (OPHLA). We used keywords for gray literature after shortlisting from the master list of keywords prepared for the academic literature search (refer to search strategy sheet).

Eligibility criteria

Studies eligible for inclusion were on the topic of HPVV; human subjects, wholly or partially targeting Canadian populations; published in English; during 2010–2019 (inclusive); and highlighted, addressed, studied, and discussed barriers and/or facilitators around the uptake of HPVV. This review included empirical studies that used any study design, any immunization program types, or study settings (i.e. community-based, publicly funded, health care based, school-based, hybrid), any serological HPV vaccine type (i.e. quadrivalent, non-valent, bivalent, etc.), all factors affecting (increase or decrease) HPV vaccine uptake and/or completion of all the HPV vaccine doses, at all levels (i.e. policy, individual, community, organizational, interpersonal, institutional, intrapersonal, etc.), and from multiple perspectives (i.e., key stakeholders, community members, parents, teachers, professionals involved in the program, young females, and males, school goers, health care, and policy practitioners, different Canadian subpopulations, i.e., refugee, immigrant, indigenous, etc.). All studies meeting inclusion criteria were included for level-1 screening.

Level-1 screening

This phase involved abstract and title screening. References identified through academic and gray literature searches were exported and assessed for level-1 screening by employing a screening tool software: DistillerSR. Studies qualified by level-1 screening were promoted to level-2 for a full-text screen.

Level 2 eligibility

This phase involved a full-text screen, also called the eligibility check. All qualified studies from level 1 were obtained in full-text form and were subjected to a full-length reading to ensure they fulfilled the eligibility criteria. DistillerSR facilitated this phase.

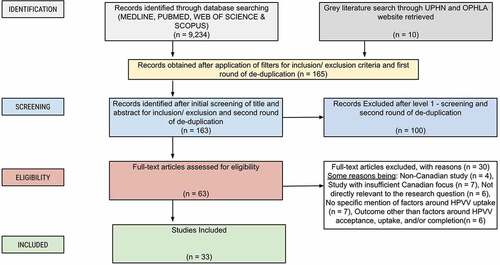

We carried out level-1 screening and level-2 eligibility checks. The PRISMA flow diagram () displays the process of its execution. Before data extraction, a senior colleague, and an expert in the field of immunization sought studies that required a second assessor agreement or a second opinion on inclusion. Utilizing the master list of keywords and MESH terminologies and with the help of a sociologist, the selection of various keywords for level-1 and level-2 screening was made after incorporating those in DistillerSR.

Data abstraction

Data on specific characteristics from the included studies were abstracted using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Version 2014). We extracted data on the following: the year of publication and data collection, study purpose, design/method(s), settings, location, population attributes, factors around the HPV vaccine uptake and/or completion (barriers/facilitators), and limitations unique to each included study.

Procedure of analysis

This review uses preexisting theoretical constructs deductively, then reaffirms the various theoretical constructs, with inductive aspects following the content analysis approach. Closely following the guidelines, we carried out interpretive content analysis by creating and assigning codes and building categories to the emerging themes from the text of the included studies.Citation22

Based on the research questions (barriers and facilitators in HPVV uptake), we selected the context to be analyzed based on the included studies. This step was followed by choosing the text called “text-selection” to be analyzed based on the medium (research studies and provincial reports)Citation23,Citation26 criteria of inclusion and selected parameters (i.e., date range, study location, study design, etc.). We then define the units and categories of analysis based on the analytical framework (). We prepared the analytical framework utilizing the following sources: Levesque’s conceptual framework,Citation16 Engel’s biopsychosocial concept model,Citation14 the system-level determinantsCitation17–19and determinants of vaccine uptakeCitation20 that integrate HPVV uptake factors at three levels.

The units and categories were coded based on the selected text’s presence and frequency of themes (including words, phrases, and characteristics). Using the pre-identified themes at three levels (patient, provider, and system), the themes that emerged in the selected text were bolded as depicted in . Following the coding rules, we similarly furthered text coding and carried out several iterations before obtaining the final set of codes. We then matched the final set of codes against the vaccine determinants at all three levels (provider, patient, and system) and synthesized results based on prominent themes based on the frequency of a particular theme(s) for barriers and facilitators in HPVV uptake. Finally, we reiterated the review’s main findings and elaborated on each, discussing the limitations of this work and implications based on the review’s findings.

Table 1. A summary of salient features of the 33 studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Table 2. Descriptive characteristics of findings from studies meeting eligibility criteria based on publication date, study settings & design/method.

Table 3. Descriptive characteristics of findings from studies meeting eligibility criteria based on vaccine receiver and provider subgroups, HPVV status, and factors around HPV immunization.

Table 4. Barriers and facilitators around human papillomavirus immunization uptake across English Canada.

Results

This review identified 9,234 references through academic literature via database searches. A Grey literature search identified additional ten references by manually searching through UPHN and OPHLA websites. After application of filters based on inclusion and exclusion criteria and carrying out the first round of deduplication, the number of identified references (N = 9,234) was reduced to 165 (refer to : PRISMA flow diagram). The studies identified were then subjected to level-1 screening and to the second round of deduplication, which excluded additional 100 references, leaving 63 for the full-text screen. A level-2 eligibility check assessed 63 references based on a full-text screen, which excluded 30 more, leaving a total of 33 references (: PRISMA flow diagram).

The reasons for the exclusion of the references from the academic literature search record included: non-Canadian studies (N = 4), insufficient Canadian focus (N = 7), not directly relevant to the review focus area (N = 6), no specific mention of factors around HPVV uptake (N = 7), and outcome other than a factor for HPVV acceptance, uptake, and/or completion (N = 6). For references from a gray literature search, the main reasons for exclusion included being outside the study period (N = 1) and the study being too broad in scope (N = 1). : The PRISMA flow diagram depicts references flow through various levels of searches and screenings in this review, accompanied by a display of reasons for exclusion. In total, 33 references (studies) qualified for inclusion. An account of all the included studies is given in .

Overview of searched literature

The results of this review are reported in two parts.

First, a tabulated display () of descriptive statistics of the literature is provided across Canadian jurisdictions based on the date of study publication (2010–14, 2015–19), study settings (school-based, community-based, hybrid), and study design/method (survey [quantitative], qualitative, cohort, cross-sectional, mixed-method, community-driven, review and reports).

Similarly, a tabulated display () of descriptive statistics on the various participant groups identified in this review and variations captured across the respective subgroups is provided and that included: 1) vaccine receivers (school/university goers, young girls and boys age > 9, parents of kids in grade > 4, newcomers, Canadian population), and vaccine providers (physicians, pharmacists, public health professionals, others), 2) HPV vaccine status (uptake, completion, catch-up, and hybrid), and 3) factors around HPV immunization at various levels (personal, system, and hybrid).

Overall, shows that more studies were conducted during the years 2015–19 than in 2010–14, mostly followed hybrid study settings (a combination of school and community based) and used a survey method. depicts that the most prominent subgroup of vaccine receivers were school/university goers, and for vaccine providers, these were physicians and others (such as nurses, etc.). Concerning HPVV status, a significant portion of the studies examined uptake rates and/or factors as opposed to vaccine completion or catch-up rates and/or factors. Interestingly, more studies reported personal factors (referred to as patient-level factors in this review) followed by system-level factors and a combination of system and personal factors.

Second, results are reported based on interpretive content analysis that alludes to the most significant barriers and facilitators in the uptake of HPVV at three levels (provider, system, and patient), drawing from the concept of the health-care equation based on the analytical framework ().

Reporting significant factors in HPVV uptake – patient level

The ability to perceive stood out as a prominent theme among the themes drawn from various coding categories, i.e., ability to seek, ability to pay, ability to perceive, ability to engage, and ability to reach. Within the identified theme (i.e., ability to perceive), knowledge insufficiency around HPVV was the main barrier to its optimal uptake.

Interestingly, ability to perceive was again found as the most prominent theme among the themes drawn from various coding categories. Within this theme (i.e., ability to perceive), knowledge sufficiency around HPVV remained the central factor in facilitating HPVV uptake.

Reporting significant factors in HPVV uptake - provider level

Content analysis revealed acceptability as the most prominent theme among the themes drawn from various coding categories, i.e., appropriateness, availability, approachability, and affordability. Overall, most studiesCitation27–29–Citation31,Citation32 identified the acceptability of the HPV vaccine as the main barrier to its uptake from a provider’s perspective. Acceptability represented issues with HPVV recommendation practices due to several interrelated factors that retard HPVV uptake.

Appropriateness was determined as the central theme among the themes drawn from various coding categories for facilitators from a provider’s perspective. ‘Appropriateness’ mainly reflected tailored interventions.

Reporting significant factors in HPVV uptake – system level

Attitude was identified as the most prominent system-level barrier to HPVV from other coding categories, i.e., cost, provision, catch-up programs, and supply chain maintenance.Citation31

It was worth noting that attitudes again stood out as the main factor that carried the potential to serve as an influential facilitator in optimizing HPVV at the system level when components of attitudes, as discussed in the discussion section, were addressed adequately (please refer to ).

Discussion

In this section, we first discuss how studies compare based on barriers and facilitators and then reiterate key findings, highlighting how they can be used to enhance HPVV uptake. This is followed by a discussion of limitations and future research.

Patient level barriers and facilitators

Concerning patient-level barriers, Fernandes et al. reported that a lack of knowledge about vaccines, their potential efficacy, side effects, and even uncertainty about vaccination cost play a significant role in HPVV uptake.Citation35 LiteratureCitation36,Citation42 reaffirmed that knowledge about HPV immunization is critical as a vast majority of parents expressed concerns about HPVV safetyCitation48 and wished to delay the HPV vaccine for their daughters due to not having enough information to make an informed decision.

Furthermore, DubeCitation3 reinforced that the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of the different players involved in the HPV vaccination system also play their role in HPVV uptake. GraceCitation29 highlighted that lack of knowledge was an influential factor around HPVV uptake as the participants had misconceptions or beliefs that HPV was predominantly or exclusively a risk for females. The same studyCitation29 also highlighted that the participants lacked knowledge about the vaccine’s availability, which indicates insufficient knowledge about HPVV.

Low literacy around the HPV vaccine has led to various misconceptions and misperceptions. Stanley reported that the most significant barrier around HPVV was adult participants’ concerns about being over the recommended age.Citation43 Also, most adult participants perceived that their own risk of HPV was low.Citation45 Moreover, parents refuse HPVV for their daughters perceiving they are not sexually active, so vaccination is unnecessary.Citation46

Finally, Scott and colleaguesCitation30 revealed that families’ lack of knowledge about the vaccine, attitudes not informed by evidence-based science, and their perception of lack of data on HPVV efficacyCitation43 are all factors contributing to misperception secondary to knowledge insufficiency.

Concerning patient-level facilitators, DubeCitation51 identified the self-estimated sufficiency of knowledge on HPVV, its perceived efficacy, and acceptability by vaccine providers and the public as important facilitators around HPVV uptake. Rambout reported that the perceived benefits of HPVV among vaccine receivers were an influential factor in its uptake.Citation47

Similarly, KrawczykCitation46 reaffirmed that parental acceptance was influenced mainly by the perceived benefits of HPVV, e.g., health protection, HPV-related cancer, and infection prevention. Along similar lines, Stanley asserted that knowledge about the importance of personal protection from HPV disease was the most common motivating factor in getting the HPVVCitation43 for oneself and in deciding for their children.

Teachers’ education on HPVV and their knowledge and understanding about the relevance of HPVV were recognized as factors of prime importanceCitation36,Citation52 as they help public health staff to distribute vaccine information material, consent forms, and set up HPV vaccine clinics in the schools. Furthermore, parents’ lack of literacyCitation48 around HPVV posed significant challenges to trusting the healthcare system and the school vaccine programs.Citation46 A studyCitation49 determining the difference in vaccine uptake between the two service delivery models (in-school and community) also examined whether socioeconomic status (SES) was a contributing factor. The studyCitation49 highlighted that girls with lower socioeconomic status were differently disadvantaged by not having access to an “in-school” vaccination. Thus, improving the overall knowledge levels around HPVV might combat factors around contextual, social normsCitation47 and cultural sensitivity.Citation36

Provider level barriers and facilitators

Concerning provider-level barriers, FerrerCitation27 and IsenorCitation33 highlighted health-care professional recommendations and provisions as significant. GraceCitation28 illuminated that health-care professional recommendation practices are limited in their perspectives on the prevention and therapeutic benefits of vaccinating specific subpopulations such as older GBM (Gay, Bisexual, and Men who have sex with men). GraceCitation28 also highlighted cost/insurance coverage, especially for some older patients, as an overarching factor that leads to inconsistent recommendation practices.

MarkowitzCitation31 expressed that uncertainty around two HPV vaccine types, the extent of catch-up vaccine programs, and the role of manufacturers and interest groups in promoting the HPV vaccine served as overarching factors in HPV vaccine recommendation practices and provisions. Moreover, WilsonCitation32 asserted that difficulties receiving agreement from local school boards to set up HPVV clinics and refusals from some Catholic schools contribute to the non-acceptability of HPVV by the school administration. ShapiroCitation38 identified that certain subgroups prefer receiving HPVV outside the school setting due to reasons, such as fear of needles and peer pressure.

GraceCitation29 reaffirmed that HPV literacy levels serve as a substantial obstacle to its provision and acceptance, and the long-standing gendered association with HPVVCitation29 further complicates this. Changing communication modes around HPVV uptake has also served as a significant barrier to accepting HPVV.Citation34

Concerning provider-level facilitators, MrklasCitation39 suggested that interventions tailored to address specific barriers to HPVV, especially relevant to contextual differences, play a vital role in increasing its uptake. The same study highlighted that tailored interventions also lessen hesitancy issues around HPV uptake. Rubens and colleaguesCitation36 encouraged targeted health promotions to enhance HPVV uptake. JaneczekCitation40 reaffirmed that interventions designed to address specific barriers unique to regional context are imperative at all levels, including vaccine receivers, health-care providers, and social marketing. JaneczekCitation40 also provided an example of a ‘tailored intervention’ appropriate to specific contexts in which school-based clinics were deemed more effective for administering HPVV.

Dube and colleaguesCitation54 reported primary schools as an effective and appropriate means to obtain higher HPV immunization coverage since HPVV is preferable before the commencement of sexual activity. WilsonCitation32 advocated for Grade 8 students to be able to request HPV immunization without parental consent if they were judged capable of providing informed consent.

Bird’sCitation37 review provided important information that could be utilized to infer gaps in the HPV delivery and administration system. BirdCitation37 reported that HPV vaccine uptake in females (57.2%) was higher than in males (47.0%) when given through school-based programs (69.6%) compared to community-based (18.66%). Furthermore, to develop a suitable intervention, HendersonCitation34 suggested establishing and strengthening community inter-generational relationships to combat trust issues in the health system. Finally, the Canadian Immunization Committee (CIC) reportCitation41 called for consideration of new and unresolved research priorities and evaluation of indicators (i.e., adequate measures to prioritize the assessments of new and ongoing HPV immunization programs) to devise locally and nationally driven policies and interventionsCitation41

System level barriers and facilitators

Attitude was the most significant factor at the system level. Attitudes reflect three main componentsCitation53. The affective component reflects a person’s feelings/emotions about the HPVV. A studyCitation51 reported physicians’ intention to recommend HPVV was perceived as acceptability by both vaccine providers (working at system level in vaccine program planning and roll-out) and vaccine receivers45,28,3. Moreover, Physicians’ self-estimated sufficiency of knowledge on HPVV and perceived efficacy of HPVV were also reported as barriers to HPVV.Citation51

The behavioral component reflects people’s attitudes and influences their behavior. From the studies discussed above, it was clear that multiple factors at all three levels (patient, provider, and system level) play a role in shaping people’s attitudes and their behavior; hence, the associated factors served as important barriers to HPVV. Some of those factors included social group values and normsCitation3 and fear of side effectsCitation46,Citation48 which might be the reasons for the parental refusal,Citation44 especially among those parents who had a previous history of refusing mandatory or optional vaccines.Citation44,Citation50 Pre-informed behaviors could also contribute to difficulty in receiving agreements from local school boards to hold HPVV clinics in schools.Citation32

The cognitive component reflects people’s belief/knowledge about HPV infection and the HPV vaccine. Studies reported people’s beliefs that HPV was either predominantly or exclusively a risk factor for females'Citation29 concerns about being over the recommended ageCitation43 doubts about vaccine safety benefitsCitation31 uncertainty around the vaccine types, and the role of manufacturers and interest group in its promotion,Citation31 all of these factors are significant barriers to optimal HPVV uptake.

The key findings from this review are as follows: (a) interrelated factors (i.e. acceptability to provide HPV vaccine recommendations and appropriateness of tailored interventions) play a role in HPV vaccine uptake at the provider level, (b) the ability to perceive (knowledge sufficiency and knowledge insufficiency) was identified as the main factor at the patient level, and (c) attitudes toward HPV vaccine (a combination of feelings/emotions, belief, behavior, and knowledge) stood out as the main factor at the system level.

Drawing on the literature reviewed, this analysis revealed that in providing HPV vaccine programming, planning, delivery, and administration services, there is no one-size-fits-all strategy that could effectively enhance HPV vaccine uptake. A combination of factors should be considered. For instance, factors that hinder the ‘acceptability’ of the HPV vaccine should be addressed to design appropriately tailored interventions that suit the context of local population subgroups to obtain optimal HPVV uptake. The identified barriers that impede providers’ abilities to make recommendations and provisions should be addressed through proper staffing, regular training of front-line providers to refine provider’s perceptions about HPV vaccine prevention and therapeutic benefits, education on the use of different communication modes to address questions and concerns around gendered association around HPV vaccine, the vaccine types, cost and insurance plan, and catch-up programs. Strategies should be in place to train providers on practicing culturally appropriate modes of communication and service delivery for different population subgroups.

Analysis of the identified literature also showed that raising awareness of HPV infection and its prevention is the strongest factor for enhancing rates of HPVV uptake. Multicomponent educational strategies should be devised, followed, and maintained in a phased manner. Educational campaigns, workshops, and advertisements on social media platforms are possible avenues for increasing awareness of this highly contagious sexually transmitted infection. Social media can be used, as it was for COVID-19, to create awareness about HPVV among the public. The literature shows that social media can serve as an excellent platform for public health intervention in raising awareness around COVID-19 infection and vaccines and addressing vaccine hesitancy.Citation55 Social media can be crucial not only in disseminating health information but can also tackle infodemics and misinformation.Citation56

The findings also reveal the attitudes of different stakeholders working at the system level in planning, programming, roll out, and delivery of HPV vaccines should be appropriately addressed. System-level workers range from medical health officers to physicians, immunization specialists, managers, and more; therefore, multifaceted strategies are required that address knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs of system-level workers to facilitate HPV vaccine provision.Citation38 Strategies could include regularly holding educational workshops, refresher courses, and feedback sessions for continuous improvement. Quality improvement surveys and audits that collect high-resolution information and investment targets should be launched and regularly operated to enhance HPV uptake by under-immunized populations.

There are limitations to this review. One of the major limitations is that it was not undertaken following a specific type of review procedures, such as systematic review, scoping review, etc. The review, however, follows an organized approach detailed throughout methods and results. We also did not carry out a quality assessment of the studies included in the review using a quality appraisal tool or checklist. Only one coder undertook coding, which precluded comparison of coding, category formation, and labeling during the analysis process. The review was limited in its scope to only English Canada; therefore, it did not include French manuscripts. Also, more than half of the included studies targeted one-time uptake of the HPV vaccine to determine vaccine status, and none embarked upon all dose series completion and/or a catch-up vaccine status. As a consequence of these limitations, the review might have missed some factors important to HPVV uptake among subpopulations who encounter unique challenges with vaccine catch-up programs or would otherwise remain unable to complete all vaccination doses against HPV infection.

There is scope for future research to explore and address factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake at all levels, i.e., provider recommendation, patient acceptance, and potent delivery by the health-care system. Improved understanding of the system-, provider-, and patient-level factors of HPVV in different jurisdictions of Canada will help target high-resolution investment targets and guide the classification of the identified barriers and facilitators according to the province-specific requirements around the country. Increased HPV vaccine uptake will help procure herd immunity against HPV, which is important to meet the target that the Government of Canada has set of reaching 90% HPVV coverage among Canadian adolescents by 2025.Citation6 Reducing the occurrence of HPV-related cancers will take Canada toward the fulfillment of an essential step toward the WHO goals of a global strategy in eliminating preventable cancer.Citation57

With a better understanding of the underlying determinants of inconsistent and sub-optimal HPV vaccination coverage, policymakers, and health-care professionals can devise effective and locally tailored interventions. This review’s findings should be used to guide future research, especially those plans to carry out population health intervention research in this topic area. There remains an urgent need to further elucidate the determinants of HPVV uptake as well as actively use knowledge already generated to formulate strategies that enhance its uptake in all jurisdictions of Canada. The existence and availability of safe and effective vaccines like the HPV vaccine in even a developed country like Canada have limited impact when their utility is not appropriately realized.

Consent for publication

I consent to publish the data and images enclosed with this submission.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Sandro Galea, Shahid Ahmed, Thilina Bandara, and Charles Plante.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Special topic: hPV-associated cancers. ( Members of the Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee, ed); 2016.

- D’souza G, Agrawal Y, Halpern J, Bodison S, Gillison ML. Oral sexual behaviors associated with prevalent oral human papillomavirus infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(9):1263–27. doi:10.1086/597755.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, Clément P, Bettinger JA, Comeau JL, Deeks S, Guay M, MacDonald S, MacDonald NE, Mijovic H, et al. Challenges and opportunities of school-based HPV vaccination in Canada. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1650–55. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1564440.

- The Canadian Cancer Society. Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada, in collaboration with the provincial and territorial cancer registries. A 2022 special report on cancer prevalence; 2022. http://cancer.ca/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2022-EN.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Wait times for priority procedures in Canada, 2021: focus on the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Published online 2021. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/wait-times-chartbook-priority-procedures-in-canada-2016-2020-en.pdf.

- Smith A, Baines N, Memon S, Fitzgerald N, Chadder J, Politis C, Nicholson E, Earle C, Bryant H. Moving toward the elimination of cervical cancer: modelling the health and economic benefits of increasing uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(2):80–84. doi:10.3747/co.26.4795.

- Cervical cancer. [Accessed 2022 Dec 1]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer.

- CDC. About HPV. Published 2020 Mar 19 [accessed 2020 Oct 7]. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/about-hpv.html.

- Lee S Human papillomavirus. Canadian Cancer Society. [Accessed 2022 Dec 1]. https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/reduce-your-risk/get-vaccinated/human-papillomavirus-hpv.

- Lee LY, Garland SM. Human papillomavirus vaccination: the population impact. F1000res. 2017;6:866. doi:10.12688/f1000research.10691.1.

- Canadian Cancer Statistics. Special topics: cancer in adolescents and young adults. ( Loraine Marrett, Prithwish De, Dagny Dryer, Larry Ellison, Eva Grunfeld, Heather Logan, Maureen Maclntyre, Les Mer, Howard Morrison. The Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee for Canadian Cancer Statistics., ed); 2009.

- Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Special Topic: HPV-Associated Cancers. ( Canadian Cancer Statistics., ed). Toronto (ON): Canadian Cancer Society; Canadian Cancer Statistics; 2016.

- McDonald JT, Kennedy S. Cervical cancer screening by immigrant and minority women in Canada. J Immigrant Min Health. 2007;9(4):323–34. doi:10.1007/s10903-007-9046-x.

- Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. J Med Philos. 1981;6(2):101–23. doi:10.1093/jmp/6.2.101.

- Israel S. How social policies can improve financial accessibility of healthcare: a multi-level analysis of unmet medical need in European countries. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):41. doi:10.1186/s12939-016-0335-7.

- Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):18. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-12-18.

- Beshears J, Choi JJ, Laibson DI, Madrian BC, Reynolds GI. Vaccination rates are associated with functional proximity but not base proximity of vaccination clinics. Med Care. 2016;54(6):578–83. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000523.

- Crawshaw AF, Farah Y, Deal A, Rustage K, Hayward SE, Carter J, Knights F, Goldsmith LP, Campos-Matos I, Wurie F, et al. Defining the determinants of vaccine uptake and under vaccination in migrant populations in Europe to improve routine and COVID-19 vaccine uptake: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(9):e254–66. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00066-4.

- Fisk RJ. Barriers to vaccination for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) control: experience from the United States. Global Health J. 2021;5(1):51–55. doi:10.1016/j.glohj.2021.02.005.

- Bhugra P, Grandhi GR, Mszar R, Satish P, Singh R, Blaha M, Blankstein R, Virani SS, Cainzos‐achirica M, Nasir K. Determinants of influenza vaccine uptake in patients with cardiovascular disease and strategies for improvement. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(15):e019671. doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.019671.

- Bibliothèque/Library. Guides de recherche research guides: systematic reviews: planning. Published online 2017 Jul 31 [accessed 2021 Apr 21]. https://uottawa.libguides.com/systematicreview/planning

- Luo A Content Analysis. Published 2019 Jul 18 [accessed 2021 Apr 21]. https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/content-analysis/

- Regional Health Authority. NB. Reasons for no or under HPV immunization-report_school-year_2015-2016- Newbrunscwick-Nb.Pdf. 2016.

- Regional Health Authority. NB. Reasons for no or under HPV immunization-report_school-year_2017-2018-Newbrunscwick-Nb.Pdf. 2017.

- Regional Health Authority. NB. Reasons for no or under HPV immunization-report_school-year_2018-2019-Newbrunscwick-Nb.Pdf. 2019.

- HPV ad hoc scientific committee. HPV vaccination in Québec: knoweledge update and expert panel proposals.Pdf. Published online 2012.

- Ferrer HB, Trotter C, Hickman M, Audrey S. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination of young women in high-income countries: a qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):700. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-700.

- Grace D, Gaspar M, Rosenes R, Grewal R, Burchell AN, Grennan T, Salit IE. Economic barriers, evidentiary gaps, and ethical conundrums: a qualitative study of physicians’ challenges recommending HPV vaccination to older gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1). doi:10.1186/s12939-019-1067-2.

- Grace D, Gaspar M, Paquette R, Rosenes R, Burchell AN, Grennan T, Salit IE. HIV-positive gay men’s knowledge and perceptions of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccination: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207953. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0207953.

- Scott K, Batty ML. HPV vaccine uptake among Canadian youth and the role of the nurse practitioner. J Community Health. 2016;41(1):197–205. doi:10.1007/s10900-015-0069-2.

- Markowitz LE, Tsu V, Deeks SL, Cubie H, Wang SA, Vicari AS, Brotherton JML. Human papillomavirus vaccine introduction – the first five years. Vaccine. 2012;30:F139–48. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.039.

- Wilson SE, Karas E, Crowcroft NS, Bontovics E, Deeks SL. Ontario’s school-based HPV immunization program: school board assent and parental consent. Can J Public Health. 2012;103(1):34–39. doi:10.1007/BF03404066.

- Isenor JE, Slayter KL, Halperin DM, McNeil SA, Bowles SK. Pharmacists’ immunization experiences, beliefs, and attitudes in New Brunswick, Canada. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2018;16(4):1310. doi:10.18549/pharmpract.2018.04.1310.

- Henderson RI, Shea-Budgell M, Healy C, Letendre A, Bill L, Healy B, Bednarczyk RA, Mrklas K, Barnabe C, Guichon J, et al. First nations people’s perspectives on barriers and supports for enhancing HPV vaccination: foundations for sustainable, community-driven strategies. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;149(1):93–100. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.024.

- Fernandes R, Potter BK, Little J. Attitudes of undergraduate university women towards HPV vaccination: a cross-sectional study in Ottawa, Canada. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):134. doi:10.1186/s12905-018-0622-0.

- Rubens-Augustson T, Wilson LA, Murphy MS, Jardine C, Pottie K, Hui C, Stafström M, Wilson K. Healthcare provider perspectives on the uptake of the human papillomavirus vaccine among newcomers to Canada: a qualitative study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1697–707. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1539604.

- Bird Y, Obidiya O, Mahmood R, Nwankwo C, Moraros J. Human papillomavirus vaccination uptake in Canada: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Prev Med. 2017;8(1):71. doi:10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_49_17.

- Shapiro GK, Guichon J, Kelaher M. Canadian school-based HPV vaccine programs and policy considerations. Vaccine. 2017;35(42):5700–07. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.079.

- Mrklas KJ, MacDonald S, Shea-Budgell MA, Bedingfield N, Ganshorn H, Glaze S, Bill L, Healy B, Healy C, Guichon J, et al. Barriers, supports, and effective interventions for uptake of human papillomavirus- and other vaccines within global and Canadian indigenous peoples: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):40. doi:10.1186/s13643-018-0692-y.

- Janeczek O Region of peel – public health. Improving Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccine uptake: a rapid review. Published online 2019.

- Canadian Immunization Committee. Recommendations for HPV immunization programs-Canadian immunization committee-SK.Pdf. Published online 2014.

- Ogilvie G, Anderson M, Marra F, McNeil S, Pielak K, Dawar M, McIvor M, Ehlen T, Dobson S, Money D, et al. A population-based evaluation of a publicly funded, school-based HPV vaccine program in British Columbia, Canada: parental factors associated with HPV vaccine receipt. PLoS Med. 2010;7(5):e1000270. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000270.

- Stanley C, Secter M, Chauvin S, Selk A. HPV vaccination in male physicians: a survey of gynecologists and otolaryngology surgeons’ attitudes towards vaccination in themselves and their patients. Papillomavirus Res. 2018;5:89–95. doi:10.1016/j.pvr.2018.03.001.

- Remes O, Smith LM, Alvarado-Llano BE, Colley L, Lévesque LE. Individual- and regional-level determinants of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine refusal: the Ontario grade 8 HPV vaccine cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1047. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1047.

- McComb E, Ramsden V, Olatunbosun O, Williams-Roberts H. Knowledge, attitudes and barriers to Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake among an immigrant and refugee catch-up group in a Western Canadian province. J Immigr Minor Health. 2018;20(6):1424–28. doi:10.1007/s10903-018-0709-6.

- Krawczyk A, Perez S, King L, Vivion M, Dubé E, Rosberger Z. Parents’ decision-making about the human papillomavirus vaccine for their daughters: iI. Qualitative results. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2015;11(2):330–36. doi:10.4161/21645515.2014.980708.

- Rambout L, Tashkandi M, Hopkins L, Tricco AC. Self-reported barriers and facilitators to preventive human papillomavirus vaccination among adolescent girls and young women: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2014;58:22–32. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.009.

- Carpiano RM, Polonijo AN, Gilbert N, Cantin L, Dubé E. Socioeconomic status differences in parental immunization attitudes and child immunization in Canada: findings from the 2013 Childhood National Immunization Coverage Survey (CNICS). Prev Med. 2019;123:278–87. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.03.033.

- Musto R, Siever JE, Johnston JC, Seidel J, Rose MS, McNeil DA. Social equity in human papillomavirus vaccination: a natural experiment in Calgary Canada. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):640. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-640.

- Shapiro GK, Tatar O, Dube E, Amsel R, Knauper B, Naz A, Perez S, Rosberger Z. The vaccine hesitancy scale: psychometric properties and validation. Vaccine. 2018;36(5):660–67. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.043.

- Dubé E, Gilca V, Sauvageau C, Bettinger JA, Boucher FD, McNeil S, Gemmill I, Lavoie F, Ouakki M, Boulianne N. Clinicians’ opinions on new vaccination programs implementation. Vaccine. 2012;30(31):4632–37. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.100.

- Whelan NW, Steenbeek A, Martin-Misener R, Scott J, Smith B, D’angelo-Scott H. Engaging parents and schools improves uptake of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: examining the role of the public health nurse. Vaccine. 2014;32(36):4665–71. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.026.

- McLeod SA Attitudes and behavior. Published online 2018 [accessed 2019 Jan 21].

- Dube E Prevention by vaccination of diseases attributable to HPV-QUBEC.Pdf. Published online 2008.

- Cascini F, Pantovic A, Al-Ajlouni YA, Failla G, Puleo V, Melnyk A, Lontano A, Ricciardi W. Social media and attitudes towards a COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review of the literature. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;48:101454. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101454.

- Tsao SF, Chen H, Tisseverasinghe T, Yang Y, Li L, Butt ZA. What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: a scoping review. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(3):e175–94. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30315-0.

- WHO. Draft: global strategy towards eliminating cervical cancer as a public health problem. Geneva, Switzerland. Published online 2019.