ABSTRACT

The biggest threat to the effectiveness of vaccination initiatives is a lack of information about and trust in immunization. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of knowledge of and positive attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine in Ethiopia. PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, EMBASE, and the Ethiopian University online library were searched. To look for heterogeneity, I2 values were computed and an overall estimated analysis was carried out. Although 2108 research articles were retrieved, only 12 studies with a total of 5,472 participants met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review and meta-analysis. The pooled estimates of participants with good knowledge of and positive attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine were found to be 65.06% (95% CI: 56.69–73.44%; I2 = 82.3%) and 60.15% (95% CI: 45.56–74.74%; I2 = 89.4%), respectively, revealing that there is a gap in knowledge of and positive attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine in Ethiopia. A holistic and multi-sectoral partnership is necessary for a successful COVID-19 vaccination campaign.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging respiratory disease caused by a single-strand, positive-sense ribonucleic acid (RNA) SARS-CoV-2 virus (abbreviation for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2).Citation1 COVID-19 causes morbidity within the range of mild respiratory disease to severe complications characterized by acute respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock, and other metabolic and hemostasis disorders and death.Citation2,Citation3

Nations have been taking various measures (travel bans and economic lockdowns, declaring states of emergencies to enforce the compulsory wearing of face masks, keeping social/physical distance, prohibition of public gatherings, and closure of faculties) to prevent the fast spread of the virus. However, poor understandings of the diseases among the community and burden of pandemic have made these measures less effective.Citation4–6

To fight the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, researchers from all over the world have made remarkable efforts to create vaccines against the disease.Citation7 Vaccination is the most effective ways of controlling infectious disease; reduce the occurrence of severe disease and death.Citation8 However, individuals and groups who choose to delay or refuse to take vaccines challenge the success of vaccine program.Citation9 Vaccine hesitancy is believed to be responsible for decreasing vaccine coverage, increased risk of vaccine preventable disease outbreaks and caused by multiple factors, mainly; due to poor knowledge and unfavorable attitude toward the vaccine.Citation10–13

Knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine is affected by lack of information or the spread of misinformation (define as incorrect or erroneous information conveyed regardless of intent to deceive) by many platforms (media, news headlines, talk programs, and popular publications) and lack of trust in immunization.Citation14–19 These factors have the potential to have serious negative repercussions, as individuals become not only uninformed but also less able to believe in scientific truths and trust experts.Citation15–18 Many people in developing nations still believe that vaccination is dangerous and unneeded,Citation20 which leads to vaccine hesitation and anti-vaccination behavior in the community.Citation18–19,Citation21–24 Therefore, studying knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine among the general population is an interesting topic to reduce COVID-19 diseases transmission rate in Ethiopia.Citation25

Based on studies conducted in different region of Ethiopia, the prevalence of good knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine among general population was between 46.8%−79.2%Citation25–31 and favorable attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine was between 24.2%−95.6%.Citation25–36 Given these variations, there is no overall estimate of the prevalence of knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine at national level. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the pooled prevalence of knowledge and attitude regarding of COVID-19 vaccine among the general population in Ethiopia. The study will provide fundamental data for policymakers, clinicians, and other stakeholders in order to help develop an appropriate strategies and interventions for COVID-19 vaccine campaign in Ethiopia.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

All studies reported the prevalence of knowledge, attitude, or both of COVID-19 vaccine, used English language for reporting, had full text available for search, done by cross-sectional study design and conducted only in Ethiopia were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. Studies reported duplicated sources, unrelated research topic, used design other than cross-sectional study, and articles with no full text available (insufficient data and outcome of interest not reported) and attempts to contact the corresponding author via e-mail not possible were excluded this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Search strategy

Both manual search (google and google scholar) and electronic search with indexed database search (PubMed, Web of Science, and EMBASE) were used to identify relevant articles. Various other gray literature databases (searching from the reference lists of the included studies, websites of government agencies and the Ethiopian institutional research repositories) were used. We applied search terms independently and/or in combination using “OR,” “AND” or “NOT.” In EMBASE, we used Boolean operators and Emtree terms (a controlled vocabulary or standard words used to make searching easier) to identify relevant articles, whereas in Web of science we used synonyms, Boolean operators, key words, and topics. In Google Scholar and other manual search, key words/phrases were used. In PubMed medical subject headings (MeSH) terms was used as follows: (((((((((((((COVID-19) OR (SARS-2)) OR (coronavirus)) OR (highly contagious diseases)) AND (vaccine)) OR (immunization)) OR (preventive measures)) OR (COVID-19 vaccine)) OR (SARS-2 vaccine)) OR (coronavirus vaccine)) AND (knowledge)) OR (awareness)) AND (attitude)) AND (Ethiopia).

The review was commenced from Oct 15, 2022 to Nov 15, 2022. All of the accessible studies that had been published in English up to Nov 15, 2022 were included in the present meta-analysis and systematic review.

In terms of reporting the findings of the literature search, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline was usedCitation37 (S1 File). The systematic review was prospectively registered on International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with unique of number CRD42022373035.

Study selection and data extraction

After imported the articles from the databases to Endnote reference manager version 7, duplicates of articles were checked and removed systematically. Three independent authors (GA, AY, and NA) have screened and reviewed the title and abstract. Any disagreement was resolved through discussions lead by a fourth author (EC). Additionally, these authors have reviewed the full text and extracted the relevant data from the articles, which fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

The name of the first author, year of publication, study region, study setting, study population, the prevalence of knowledge of COVID-19 vaccine, the prevalence of attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccine, sample size, number of cases of knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine, number of cases of attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine were extracted carefully on an Excel spreadsheet.

Quality assessment

The two independent authors (GA and NA) appraised the quality of the included studiesCitation25–36 using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal checklist for cross-sectional studies.Citation38 Any disagreement was discussed and resolved by the third author (MM). The critical analysis checklist has eight parameters with yes, no, unclear, and not an applicable options. Studies were considered low risk when they scored 50% and above of the quality assessment indicators as reported in supplementary file (S2 File).

Risk of bias assessment

This systematic review and meta-analysis study used a risk of bias assessment tool developed by Hoy et alCitation39 consisting of 10 items that assess four domains of bias, internal and external validity. The risk of bias was assessed by three independent authors (DN, MA, KD) for included studies.Citation25–36 The first four items (items1–4) evaluate the presence of selection bias, non-response bias and external validity. The other six items (items 5–10) assess the presence measurement bias, analysis-related bias, and internal validity. Therefore, studies that received ‘yes’ for eight or more of the 10 questions were classified as ‘low risk of bias.’ Studies that received ‘yes’ for six to seven of the 10 questions were classified as ‘moderate risk’, whereas studies that received ‘yes’ for five or fewer of the 10 questions were classified as ‘high risk’ as reported in (S3 File).

Outcome measurement

Knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine

Study participants who responded ≥50% of knowledge-related questions were thought to have good knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine, whereas study participants who responded ≤50% of knowledge-related questions were considered to have poor knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine.

Attitude toward the COVID-19 vaccines

Accordingly, study participants who responded ≥50% of attitude-related questions were considered to have positive attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine, whereas study participants who responded ≤50% of attitude-related questions were considered to have negative attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine

Statistical analysis

Firstly, selected articles were entered into Microsoft Excel spreadsheet format and imported to STATA version 14. statistical software for analysis. Weighted inverse variance random effect model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine among the general population in Ethiopia. We used random effect model because there is heterogeneity between studies. Cochrane Q-test and I2 statistics were computed to assess heterogeneity among all studies. Accordingly, values of I2 0, 25, 50, and 75% represented no, low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively.

Funnel plot, Begg and Egger’s regression tests were done to assess publication bias. The p value > .05 indicated that there was no publication bias. A trim and fill analysis was done to see the effect of publication bias.

Subgroup analysis was done based on the study region, study population and year of publication. Forest plot format was used to present the pooled prevalence knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine with 95%CI.

Results

Search results

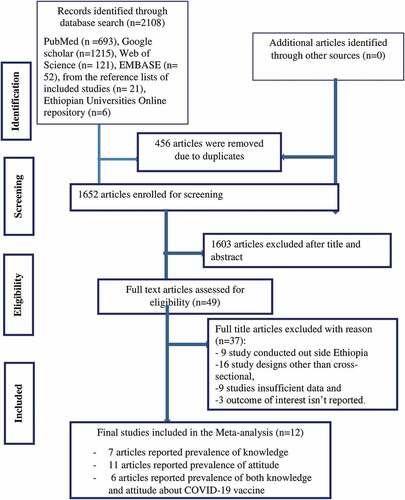

There were 2108 articles found in the databases including, 693 from PubMed, 1215 from Google Scholar, 52 from EMBASES, 121 from Web of sciences, 6 from Ethiopian universities’ research repositories, and 21 from the reference lists of included studies. While a total of 2096 articles were excluded due to various reasons. For instance, 456 articles were removed because of duplicates, 1603 due to irrelevant titles and abstracts, 16 due to the study designs, 9 due to study areas, 9 insufficient data and 3 outcome of interest not reported. Finally, 12Citation25–36 articles were included in the study. From the included studies, seven articles, 11 articles, and 6 articles reported prevalence of knowledge, attitude, and both knowledge and attitude about COVID-19 vaccine ().

Characteristics of included studies

In this study, a total of 12 articlesCitation25–36 with a sample size of 5,472 study participants were included in the analysis. The author’s names, publication year, study design, sample size, study setting, the prevalence of knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine, number of cases of knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine were listed.

The majority of the studies (4 articles)Citation25–28 were conducted in the South Nation Nationalities and Peoples’ region (SNNP), three from Amhara,Citation29,Citation31,Citation33 one from Oromia,Citation36 one from Adis AbabaCitation30 and the remaining three studies were conducted through an online survey by sending the questionnaire through e-mail, telegram, and other means of communication for those who able to access the internet.Citation32,Citation34,Citation35 Regarding publication year, the earliest in 2021 and the latest in Sep 29, 2022. The sample sizes ranged from 319 to 668. The prevalence of knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine were ranged from 46.8% to 79.2% and 24.2 to 95.6%, respectively. From the included studies, seven articles, 11 articles, and 6 articles reported prevalence of knowledge, attitude, and both knowledge and attitude about COVID-19 vaccine. All 12 studies were assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal checklist. Two of the included studies had reported moderate riskCitation31,Citation34 and the rest had reported low risk. A detailed description of the studies was found in .

Table 1. Descriptions of the studies used in the systematic review and meta-analysis for the knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine in Ethiopia.

Level of knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine

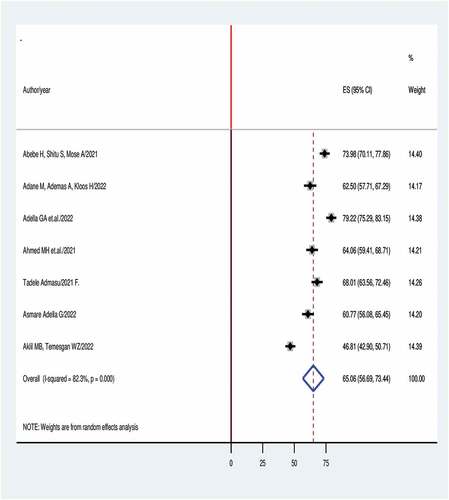

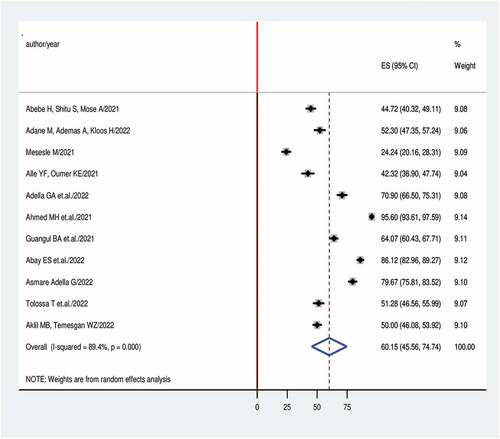

The pooled prevalence of the knowledge about and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccine among the general population in Ethiopia is presented by the forest plots in . A random-effect model showed that the pooled level of good knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine was 65.1% (95% CI: 56.7–73.4%; I2 = 82.3%). The overall pooled estimated positive attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine was 60.2% (95% CI: 45.6–74.7%; I2 = 89.4%) ().

Figure 2. Forest plot of knowledge with the height of the diamond is the overall effect size (ES) (65.1%) while the width is the confidence interval (CI) at 95% (56.7–73.4%). The y-axis shows the standard error of each study while the x-axis the estimate of effect size of the each study. The vertical dotted line denotes the no effect. The box represents the effect size of each study and the line across the box is confidence interval of each study.

Figure 3. Forest plot of attitude with the height of the diamond is the overall effect size (ES) (60.2%) while the width is the confidence interval (CI) at 95% (45.6–74.7%). The y-axis shows the standard error of each study while the x-axis the estimate of effect size of the each study. The vertical dotted line denotes the no effect. The box represents the effect size of each study and the line across the box is confidence interval of each study.

Leave – one- out sensitivity analysis

A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to show the influence of each study on the pooled prevalence of a good level of knowledge about and a positive attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine by excluding one study at a time.

Based on the finding from sensitivity analysis, two studies in the review had an impact on the pooled level of good knowledge about COVID-19 vaccineCitation28,Citation31 and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccineCitation26,Citation32 ().

Table 2. A leave – out-one sensitivity analysis for knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine in Ethiopia.

Subgroup analysis

In this subgroup analysis, the level of good knowledge and positive attitude toward COVID-19 were examined by study region, study population, and year of publication. The subgroup analysis based on region showed that a level of good knowledge were 69.6% in SNNP region, 54.6% in Amhara region and 68.0% in Adis Ababa. Based on study population, 74.0% in adult population (age>18), 63.3% in healthcare workers and 46.8% in college students. Based on year of publication, 68.8% of a good level of knowledge was in 2021 and 62.3% in 2022.

With regard to positive attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine, the subgroup analysis based on region showed that 72.8% in SNNP region, 48.4% in Amhara region, 58.2% at national level and 51.3% in Oromia region. Based on study population, 44.7% in adult population (age > 18), 65.4% in health-care workers and 50.0% in college students. Based on year of publication, 54.2% of a positive attitude was in 2021 and 65.1% in 2022 ().

Table 3. The overall estimated level of good knowledge and positive attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine in Ethiopia, 95% CI and heterogeneity estimate with a p-value for sub-group analysis.

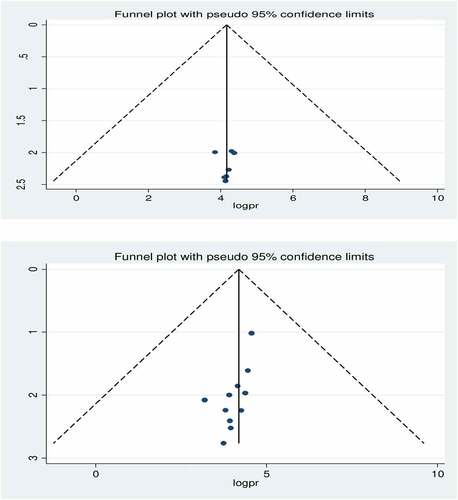

Publication bias

The presence of publication bias was checked using funnel plot visualization and Egger’s and Begg’s regression tests (P < .05). The funnel plot visualization was symmetric distribution for good level of knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine. The Egger and Begg tests both revealed no statistical evidence of publication bias for a good level of knowledge (P = .9 and P = .4, respectively).

The funnel plot visualization was asymmetric distribution for positive level of attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine, but the results of the Begg (P = .1) and Egger (P = .1) tests showed the absence of publication bias ().

Figure 4. For the top figure funnel plot showing symmetrical distribution of studies indicating the visual absence of publication bias for included studies reporting knowledge. For the bottom figure funnel plot showing asymmetrical distribution of studies indicating the visual presence of publication bias for included studies reporting attitude. For both the top and bottom figures, the Y-axis is the standard error and the X-axis is the study result or effect size. The dotted diagonal line of the funnel is the 95% confidence interval and the vertical. The vertical dotted line is the line of no-effect and dots are included studies reporting knowledge of and attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine.

Discussion

Due to the scant availability of literature, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to better understand attitudes and levels of knowledge regarding the COVID-19 vaccine among the general population in Ethiopia. We included all eligible studiesCitation25–36 found via a variety of electronic search engines and undertook a subgroup analysis to assess the proportion of people with good knowledge and positive attitudes by study region, study population and year of publication.

This study’s findings revealed that the pooled prevalence of good knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine was 65.1% (95% CI: 56.7–73.4%), which was consistent with a study conducted in Bangladesh (62.1%)Citation40 and higher than in West India (35.5%) and Malaysia (38.0%).Citation41,Citation42 However, levels of good knowledge were higher than our finding in Greece (88.3%), Oman (88.4%) and Romania (95.2%).Citation43–45 This could be attributed to variations in the spread and burden of COVID-19 across these countries.Citation46 The discrepancy could also be due to differences in the respondents’ local norms and cultures and exposure to credible social media disseminating information regarding the vaccine.Citation47,Citation48 The variation could also be explained by differences in awareness of the severity of COVID-19 and access to healthcare services. The pooled prevalence showed that significant numbers of Ethiopians (about 35.0% of the study population) had poor knowledge of the COVID-19 vaccine. This implies that improving knowledge regarding the benefits, effectiveness, and safety of the COVID-19 vaccine could be a strategy for achieving vaccination coverage goals in the general population. Having good knowledge is a driver for receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, as it helps individuals understand the seriousness of the disease and the benefits of vaccination.

This study’s findings revealed that the pooled prevalence of positive attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine was 60.2% (95% CI: 45.6–74.7%), which was consistent with studies done in Belgium (72.4%) and Italy (50.0%)Citation49,Citation50 and higher than in studies examining the UK (36.9%) and Egypt (34.3%).Citation51,Citation52 This variation may be explained by differences in culture, socio-economic status, and health policy implementation.

The results of the subgroup analysis indicated that the pooled proportion of positive attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers in Ethiopia was 65.4%. This implies that a considerable proportion of healthcare workers hold unfavorable views, making them less likely to recommend vaccination to their patients. Evidence indicates that healthcare workers’ attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine were found to influence their intention to suggest the vaccine to their patients and the general population.Citation53 Hence, future educational priorities need to focus on healthcare workers to influence their own use of the vaccine and help the general population accept vaccination.

In this study, we used a random-effect model to manage a significant variation that resulted in between-study heterogeneity. We assessed leave-one-out sensitivity and the results show that every study had a significant impact on the pooled good level of knowledge and positive attitudes. We also assessed possible variability sources via subgroup analysis using the study populations and regions and years of publication. The high degree of heterogeneity may be due to differences in the sample populations, paper quality, or socio-cultural, ethnic, and regional differences.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strengths of the study include the use of a comprehensive electronic search strategy through a variety of datasets to determine overall levels of knowledge and attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine, the use of JBI-MAStARI appraisal, and access to gray literature. The limitations included the absence of standard measurement of ‘good knowledge’ and ‘positive attitude’ among different groups of the population that the research team could operationalize, and the research may be biased. The absence of a similar previous study makes it very difficult to compare the findings of this study. Predictors of knowledge and attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine were missed. Hence, future researchers should consider the factors related to knowledge and attitudes regarding the COVID-19 vaccine. Since some regions did not report knowledge or attitude data, the results of this study were not representative of all regions in Ethiopia.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis reported that there was a significant gap in good knowledge of and positive attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine in Ethiopia. In addition, the pooled prevalence of good knowledge and positive attitudes differed based on study populations, regions and years of publication. A holistic and multi-sectoral partnership is necessary for a successful COVID-19 vaccination campaign. Further health education and communication are crucial methods for improving knowledge and attitudes regarding the COVID-19 vaccine, and finally, to improve vaccine acceptance.

Authors’ contribution

All authors made considerable contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or evaluation and interpretation of data; took section in drafting the article or revising it significantly for necessary intellectual content; agreed to put up to the current journal; gave ultimate approval of the version to be published; and agree to be responsible for all elements of the work.

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analyzed during study are included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent to participate are not applicable since we used already previously done research.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (389.4 KB)Acknowledgments

Our special gratitude goes to the authors of included studies who helped us to do this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2179224

Additional information

Funding

References

- Masters PS. 2019. Coronavirus genomic RNA packaging. Virology. 537(August):198–11. doi:10.1016/jvirol201908031.

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):5 07–513. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7.

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, et al. 2020. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 323(11):1061–69. doi:10.1001/JAma.2020.1585.

- Mehtar S, Preiser W, Lakhe NA, Bousso A, TamFum JJM, Kallay O, Seydi M, Zumla A, Nachega JB. Limiting the spread of COVID-19 in Africa: one size mitigation strategies do not fit all countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(7):e881–83. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30212-6. PMID: 32530422.

- FDRE (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia). COVID-19 state of emergency. Addis Ababa: FDRE; 2020.

- Overview of Public Health and Social Measures in the Context of COVID-19. Interim Guidance, World Health Organization; 2020. file:///C:/Users/user/Downloads/WHO-2019-nCoVPHSM_Overview-2020.1-eng.pdf

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). First COVID-19 vaccine authorized for use in the European Union. Stockholm: ECDC; 2020 [accessed 2021 May 19. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/first-Covid-19-vaccine-authorised-use-europeanunion

- Paterson P, Meurice F, Stanberry LR, Glismann S, Rosenthal SL, Larson HJ. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine. 2016 Dec 20;34(52):6700–06. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042.

- Lurie N, Saville M, Hatchett R, Halton J. Developing COVID-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. N Engl J Med. 2020 May 21;382(21):1969–1973. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2005630.

- MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015 Aug 14;33(34):4161–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Di MG, Di GP, Di GA, Scampoli P, Cedrone F, D’addezio M, Meo F, Romano F, Di Sciascio MB, Staniscia T. 2020. Knowledge and attitude towards vaccination among healthcare workers: a multicenter cross-sectional study in a Southern Italian Region. Vaccines. 8(2):248. doi:10.3390/vaccines8020248.

- Lee H, Moon SJ, Ndombi GO, Kim K-N, Berhe H, Nam EW. 2020. Covid-19 perception, knowledge, and preventive practice: comparison between South Korea, Ethiopia, and democratic republic of congo. Afr J Reprod Health. 24(s1):66–77. doi:10.29063/ajrh2020/v24i2s.11.

- Zhang KC, Fang Y, Cao H, Chen H, Hu T, Chen Y, Zhou X, Wang Z. 2021. Behavioral intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese factory workers: cross-sectional online survey corresponding author. J Med Internet Res. 23(3):1–17. doi:10.2196/24673.

- Farrell J, McConnell K, Brulle R. 2019. Evidence-based strategies to combat scientific misinformation. Nat Clim Chang. 9(3):191–95. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0368-6.

- Koulolias V, Jonathan GM, Fernandez M, Sotirchos D. Combating misinformation: an ecosystem in co-creation. UK: OECD Publishing; 2018. p. 30

- Safieddine F, Dordevic M, Pourghomi P, editors. Spread of misinformation online: simulation impact of social media newsgroups. 2017 Computing Conference. London, UK: IEEE; 2017. p. 899-906. doi: 10.1109/SAI.2017.8252201.

- Ullah I, Khan KS, Tahir MJ, Ahmed A, Harapan H. 2021. Myths and conspiracy theories on vaccines and COVID-19: potential effect on global vaccine refusals. Vacunas. 22(2):93–97. doi:10.1016/j.vacun.2021.01.001.

- Wirsiy FS, Nkfusai CN, Ako-Arrey DE, Kenfack Dongmo E, Titu Manjong F, Nambile Cumber S. 2021. Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine in Africa. Int J Maternal Child Health AIDS. 10(1):134. doi:10.21106/ijma.482.

- Donato KM, Singh L, Arab A, Jacobs E, Post D. Misinformation about COVID-19 and Venezuelan migration: trends in Twitter conversation during a pandemic. Harvard Data Sci Rev. 2022. doi:10.1162/99608f92.a4d9a7c7.

- Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger JA. 2013. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 9(8):1763–73. doi:10.4161/hv.24657.

- Hayawi K, Shahriar S, Serhani MA, Taleb I, Mathew SS. 2022. Anti-Vax: a novel Twitter dataset for COVID-19 vaccine misinformation detection. Public Health. 203:23–30. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2021.11.022.

- Kalayou MH, Tilahun B, Endehabtu BF, Nurhussien F, Melese T, Guadie HA. 2020. Information seeking on Covid-19 pandemic: care providers’ experience at the university of Gondar teaching hospital, Northwest of Ethiopia. J Multidiscip Healthc. 13:1957. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S283563.

- O’neil M, Khan I, Holland K, Cai X. Communication, society. Mapping the connections of health professionals to COVID-19 myths and facts in the Australian Twittersphere. Info Common Soc. 2022;1–23. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2022.2032260.

- Yigit M, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, Senel E. Evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine refusal in parents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40(4):e134–6. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000003042.

- Abebe H, Shitu S, Mose A. 2021. Understanding of COVID-19 vaccine knowledge, attitude, acceptance, and determinates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among adult population in Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 14:2015. doi:10.2147/IDR.S312116.

- Ahmed MH, Siraj SS, Klein J, Ali FY, Kanfe SG. 2021. Knowledge and attitude towards second COVID-19 vaccine dose among health professionals working at public health facilities in a low income country. Infect Drug Resist. 14:3125. doi:10.2147/IDR.S327954.

- Asmare Adella G. Knowledge and attitude toward the second round of COVID-19 vaccines among teachers working at southern public universities in Ethiopia. Hum Vacc Immunotherapeut. 2022 Jan;18(1):1–7. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2018895.

- Adella GA, Abebe K, Atnafu N, Azeze GA, Alene T, Molla S, Ambaw G, Amera T, Yosef A, Eshetu K, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and intention to accept COVID-19 vaccine among patients with chronic diseases in southern Ethiopia: multi-center study. Front Public Health. 2022;10. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.917925.

- Adane M, Ademas A, Kloos H. Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of COVID-19 vaccine and refusal to receive COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers in northeastern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2022 Dec;22(1):1–4. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-12362-8.

- Tadele Admasu F. Knowledge and proportion of COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors among cancer patients attending public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021: a multicenter study. Infect Drug Resist. 2021 Nov;Volume 14:4865–76. doi:10.2147/IDR.S340324.

- Aklil MB, Temesgan WZ. Knowledge and attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors among college students in Northwest Ethiopia, 2021. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. 2022 May;9:23333928221098903. doi:10.1177/23333928221098903.

- Mesesle M. 2021. Awareness and attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Infect Drug Resist. 14:2193. doi:10.2147/IDR.S316461.

- Alle YF, Oumer KE. Attitude and associated factors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health professionals in Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, North Central Ethiopia; 2021: cross-sectional study. Virusdisease. 2021 Jun;32(2):272–78. doi:10.1007/s13337-021-00708-0.

- Guangul BA, Georgescu G, Osman M, Reece R, Derso Z, Bahiru A, Azeze ZB. Healthcare workers attitude towards SARS-COVID-2 vaccine, Ethiopia. Global J Infect Dis Clin Res. 2021 Jun 29;7(1):043–8. doi:10.17352/2455-5363.000045.

- Abay ES, Belew MD, Ketsela BS, Mengistu EE, Getachew LS, Teferi YA, Zerihun AB, Pakpour AH. Assessment of attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among clinical practitioners in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PloS One. 2022 Jun 16;17(6):e0269923. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0269923.

- Tolossa T, Wakuma B, Turi E, Mulisa D, Ayala D, Fetensa G, Mengist B, Abera G, Merdassa Atomssa E, Seyoum D, et al. Attitude of health professionals towards COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors among health professionals, Western Ethiopia: a cross-sectional survey. PloS One. 2022 Mar 9;17(3):e0265061. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265061.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA GroupThe Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. PMID: 19621072.

- Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews Checklist for Prevalence Studies. Adelaide, South Australia: Joanna Briggs Institute; Adelaide; 2017.

- Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, Baker P, Smith E, Buchbinder R. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. PMID: 22742910.

- Islam MS, Siddique AB, Akter R, Tasnim R, Sujan MS, Ward PR, Sikder MT. Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions towards COVID-19 vaccinations: a cross-sectional community survey in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2021 Jan 1;21(1). 10.1186/s12889-021-11880-9.

- Mohamed NA, Solehan HM, Mohd Rani MD, Ithnin M, Che Isahak CI, Sobh E. Knowledge, acceptance, and perception on COVID-19 vaccine among Malaysians: a web-based survey. PloS One. 2021 Aug 13;16(8):e0256110. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0256110.

- Bhartiya S, Kumar N, Singh T, Murugan S, Rajavel S, Wadhwani M. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards COVID-19 vaccination acceptance in West India. Int J Commun Med Public Health. 2021;8(3):1170. doi:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20210481.

- Papagiannis D, Malli F, Raptis DG, Papathanasiou IV, Fradelos EC, Daniil Z, Rachiotis G, Gourgoulianis KI. 2020. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) of health care professionals in Greece before the outbreak period. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(14):1–14. doi:10.3390/ijerph17144925.

- Al-Marshoudi S, Al-Balushi H, Al-Wahaibi A, Al-Khalili S, Al-Maani A, Al-Farsi N, Al-Jahwari A, Al-Habsi Z, Al-Shaibi M, Al-Msharfi M, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) toward the COVID-19 vaccine in Oman: a pre-campaign cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021 Jun;9(6):602. doi:10.3390/vaccines9060602.

- Popa GL, Muntean AA, Muntean MM, Popa MI. Knowledge and attitudes on vaccination in southern Romanians: a cross-sectional questionnaire. Vaccines. 2020;8(4):1–7. doi:10.3390/vaccines8040774.

- Keni R, Alexander A, Nayak PG, Mudgal J, Nandakumar K. 2020. COVID-19: emergence, spread, possible treatments, and global burden. Front Public Health. 8:216. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00216.

- Chan NN, Ong KW, Siau CS, Lee KW, Peh SC, Yacob S, Chia YC, Seow VK, Ooi PB. The lived experiences of a COVID-19 immunization programme: vaccine hesitancy and vaccine refusal. BMC Public Health. 2022 Dec;22(1):1–3. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-12632-z.

- Singh A, Lai AH, Wang J, Asim S, Chan PS, Wang Z, Yeoh EK. Multilevel determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among South Asian ethnic minorities in Hong Kong: cross-sectional web-based survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021 Nov 9;7(11):e31707. doi:10.2196/31707.

- Verger P, Scronias D, Dauby N, Adedzi KA, Gobert C, Bergeat M, Gagneur A, Dubé E. Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: a survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada, 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2021 Jan 21;26(3):2002047. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.3.2002047.

- La Vecchia C, Negri E, Alicandro G, Scarpino V. Attitudes towards influenza vaccine and a potential COVID-19 vaccine in Italy and differences across occupational groups, September 2020. Med Lav. 2020;111:445.

- Paul E, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: implications for public health communications. Lancet Reg Health-Europe. 2021 Feb 1;1:100012. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012.

- Omar DI, Hani BM. Attitudes and intentions towards COVID-19 vaccines and associated factors among Egyptian adults. J Infect Public Health. 2021 Oct 1;14(10):1481–88. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2021.06.019.

- Iguacel I, Maldonado AL, Ruiz-Cabello AL, Samatán E, Alarcón J, Ángeles Orte M, Santodomingo Mateos S, Martínez-Jarreta B. Attitudes of healthcare professionals and general population toward vaccines and the intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19 in Spain. Front Public Health. 2021;9. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.739003.