ABSTRACT

Vaccination for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is important to reduce rates of cervical and oropharyngeal cancer. We aimed to evaluate if a program to initiate HPV vaccination at 9 years improved initiation and completion rates by 13 years of age. Data on empaneled patients aged 9–13 years from January 1, 2021 to August 30, 2022 were abstracted from the electronic health record. Primary outcome measures included HPV vaccination initiation and series completion by 13 years of age. The secondary outcome measure was missed opportunities for HPV vaccination. In total, 25,888 patients were included (12,433 pre-intervention, and 13,455 post-intervention). The percentage of patients aged 9–13 with an in-person visit who received at least 1 dose of HPV vaccine increased from 30% pre-intervention to 43% post-intervention. The percentage of patients who received 2 doses of vaccine increased from 19.3% pre-intervention to 42.7% post-intervention. For the overall population seen in-person, initiation of HPV vaccination by age 13 years increased from 42% to 54%. HPV completion increased as well (13% to 18%). HPV vaccination initiation at 9 years of age may be an acceptable and effective approach to improving vaccination rates.

Introduction

Over 35,900 men and women in the United States are diagnosed with cancer caused by the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) each year.Citation1 Oropharyngeal cancer is the most common cancer associated with HPV infection followed by cervical cancer.Citation2 Vaccination against HPV substantially reduces the risk of HPV associated cancers.Citation2,Citation3 It is estimated that HPV vaccination could prevent more than 90% of cancers caused by HPV or roughly 33,000 cases every year.Citation4

Initiation of HPV vaccination is recommended for children at the age of 11–12 years and may begin at 9 years of age.Citation5,Citation6 Initiation at ages less than 12 years allows for a more robust immune response developmentCitation1 and provides a longer period of time to achieve completion of the vaccine series before potential exposure to HPV at sexual debut. The United States has had low uptake of HPV vaccination with only 76.9% initiation and 61.7% completion in 2021Citation7 Initiation and completion rates can be low from a variety of reasons including that adolescents seek care less often than younger children,Citation8 particularly after completion of the 11 year old vaccine requirements. This can make it challenging to complete the multi-dose vaccine series. The current vaccine series recommends 2 doses 6 to 12 months apart if initiated at age less than 15 years or 3 doses (0, at least 1 month, at least 6 months) if initiated at age 15 years or greater.Citation5,Citation6 According to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), adolescents are considered fully vaccinated if they have had one dose of meningococcal vaccine, one tetanus, diphtheria toxoids and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine, and have completed the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine series by their 13th birthday.Citation9 A study by St Sauver et al.Citation10 showed that when HPV vaccination was initiated at 9 or 10 years of age, they were more likely to complete the series as compared to a similar cohort aged 11 or 12 years old.

Similar to other systems, Denver Health and Hospital Authority (DHHA) in Denver, Colorado saw overall decreased rates of childhood immunizations for children over the age of 2 years old, including HPV immunization, during the pre-vaccine phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020 – approximately mid-May 2021). This was likely from a reduction in patients seeking care, particularly well child care.Citation11 In May of 2021, the Pediatric Quality Improvement (QI) team at DHHA modified institutional guidelines to decrease the standard age of initiation of the HPV vaccination series to age 9 years in order to improve vaccination rates. A comprehensive QI program for initiation of HPV vaccination at first opportunity (age 9) was simultaneously implemented. In this exploratory analysis, we aimed to evaluate if a program to initiate HPV vaccination at age 9 years improved HPV initiation and completion rates by 13 years of age.

Materials and methods

Setting

The intervention took place at DHHA in Denver, CO which includes 28 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) which are all a part of Vaccines For Children Program (VFC).Citation12,Citation13 The population served by DHHA is racially and ethnically diverse with patients in 2018 identifying as 58% white, 26% black, and 15% other/unknown race; 47% of patients identified as Hispanic. In addition, more than 75% of patients have public insurance or are self-pay.Citation12

Intervention

Children eligible and due for any vaccines are offered vaccination at any outpatient (except for telehealth visits) and inpatient visits. DHHA employs ‘standing orders’ which allow authorizing nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals to assess patient vaccine status and administer needed vaccinations without examination or direct order from the attending provider.Citation14 This practice saves time and reduces missed opportunities for vaccination. In the May of 2021, the DHHA Pediatric Quality Improvement Workgroup, Immunization Workgroup and Ambulatory Quality Improvement Committee unanimously approved a change in institutional recommendations to initiate HPV vaccination at age 9 for all patients. This change spanned all primary care specialties that see children (family medicine, pediatrics, school-based, and internal medicine/pediatrics). Best Practice Advisories (BPAs) are alerts within our electronic health record (EHR) (EPIC; Verona, WI) that allow medical assistants and other health professionals to know that a patient is due for vaccination. The BPA for HPV vaccination initiation was changed from 11 years old to 9 years old at the end of May 2021 to alert the medical assistant that any 9-year-old seen for an in-person visit (well and acute visits) would be eligible to receive an HPV vaccination. Brief education was provided to clinical staff including engagement of clinical and EHR champions who educate and train their clinical team on QI changes. These champions are asked to relay changes to their clinical team. At the end of 2021, it was also added to an institutional dashboard that monitors quality metrics by month and provides data on missed opportunities to vaccinate at the clinic, provider, and medical assistant levels (see Supplementary Table).

Population and data abstraction

Patient data from January 1, 2021 to August 30, 2022 were electronically abstracted from the DHHA EHR (EPIC; Verona, WI). Empaneled patients aged 9–13 years, defined as those patients who had been seen in a primary care clinic within the last 18 months, were included as a denominator of possible patients who could be affected by the intervention. To calculate missed opportunities to vaccinate in clinics, only active patients defined as patients who had had an in-person visit in primary care (acute or well visit) at DHHA between January 1, 2021 to August 30, 2022, were included. Patients with telehealth visits or nurse-line visits were excluded from the evaluation of missed-opportunities. The pre- intervention period included 5 months while the post-intervention period included 14 months due to COVID-19 pandemic disruption in child and adolescent vaccination. We abstracted data on demographics, encounter data (types of visits (in-person v other), eligibility for HPV vaccination, action taken on BPAs and HPV vaccination status.

Outcome measures

In alignment with HEDIS measuresCitation9 the primary outcome measures were (1) HPV vaccine initiation by 13 years of age and (2) HPV vaccination series completion by 13 years of age. The secondary outcome measure was missed opportunity for HPV vaccination. We defined a missed opportunity as an in-person visit (acute or well) at primary care clinic where a patient was eligible for HPV vaccination and was not vaccinated.

Data analysis

Because this was an exploratory analysis, descriptive statistics were computed (number and percentage) by month. The project was reviewed by Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board at the University of Colorado, Denver and was exempted as it was determined not to be human subjects research.

Results

Participant demographics

In total, 25,888 patients, from 9 to 12 + 364 days, were included; 12,433 in the pre-intervention, and 13,455 in the post-intervention periods. The mean ages of included patients pre- and post-intervention were 10.61 and 10.59 years respectively. The number of empaneled patients increased over the time period. For both groups (pre-; post-intervention), the majority of patients were white (66.3%; 66.4%), Hispanic(69.4%; 67.7%), spoke English (56.4%; 57.6%) and utilized Medicaid (85.7%; 84.0%). There were similar numbers of males and females (Demographics; ).

Table 1. Demographics of patients.

HPV vaccination initiation

The percentage of patients aged 9–13 with an in-person visit who received at least 1 dose of HPV vaccine by age 13 years increased from 30.3% (n = 3,767) pre-intervention to 42.8% (n = 5,764) post-intervention. The percentage of patients with an in-person visit who received two doses of vaccine by age 13 years increased from 19.3% (n = 2,403) pre-intervention to 42.7% (n = 5,741) post-intervention (Demographics; ).

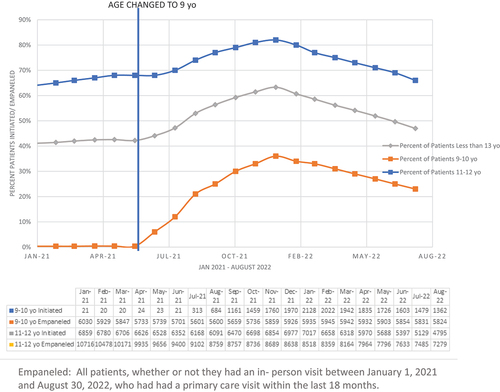

In total, 0.4% of all empaneled patients 9–10 years (inclusive) initiated HPV vaccination by age 11 pre-intervention vs an average of 24% post-intervention. Post-intervention there was a rise in initiation to a peak of 44% in January 2022 with a decrease to 23% thru August 2022. For those 11–12 years (inclusive) 66% initiated HPV vaccination pre-intervention vs an average of 74% post-intervention. Post-intervention there was a rise in initiation to a peak of 82% in January 2022 with a decrease to 66% thru August 2022. Overall, initiation of HPV vaccination 9–12 years (inclusive) increased from 42% in the pre-intervention period to 54% in the post-intervention period with a rise to 63% in January 2022 and then a decrease to 47% thru August 2022 (Difference 12%; ).

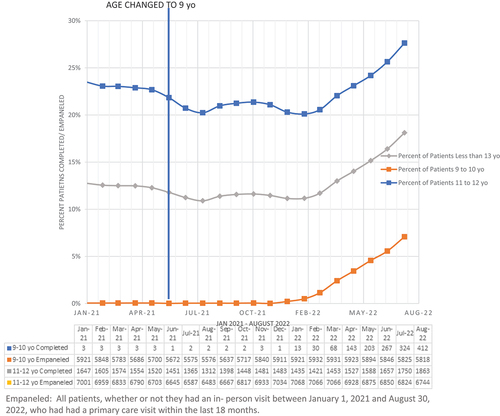

HPV vaccination completion

The percent of empaneled patients who were 9–10 years (inclusive) who were up-to-date for HPV vaccination was 0.1% pre- intervention and increased to 2% of patients post-intervention. For those 11–12 years (inclusive), 23% patients were up-to-date for HPV vaccination pre-intervention vs 22% post-intervention. Overall, completion rates of the HPV vaccination series for empaneled patients 9–12 years (inclusive) remained stable at 13% in the pre- and post-intervention periods. However, these HPV vaccine completion rates, steadily increased starting in February 2022 (8 months post-intervention) and reached 18% by August 2022 ().

Missed opportunities

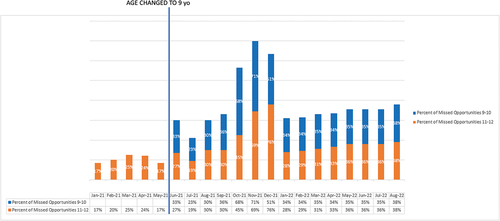

The rate of missed opportunities (those patients seen in-person during the pre- and post-intervention time periods) was 39% post-intervention in patients 9 to 11 years old. For these patients only data on missed opportunities in the post-intervention period was available. For those 11 up to 13 years, the percent of missed opportunities increased from 21% pre- intervention to 38% post intervention ().

Discussion

In this descriptive evaluation we found that changing the age of initiation of HPV vaccination to 9 years of age increased the rate of HPV vaccination initiation by 13 years of age. Overall average vaccine completion rates were 13% in both periods but over the post-intervention study period, the monthly rates increased steadily from 13% to 18%. Because this period lasted only 15 months, we did not expect an increase in HPV vaccine series completion by age 13 years. It is not clear if the increase in completion rates was from the intervention or from increased volumes of children presenting to clinics during the vaccine-era of the pandemic. There was high uptake of HPV vaccination among children 9–10 years old.

There are several possible explanations for the low HPV vaccination rates of empaneled patients. The primary driver of low rates was likely that empaneled patients did not seek care in a primary care clinic during the time period. This effect may have been exemplified by reductions in care seen as a result of the pandemic, including a reduction in acute visits from enhanced social distancing measures in the community. In the post-intervention period, when eligible patients were in clinic, they were offered and accepted a vaccine nearly 66% percent (total intervention period) of the time. The total number of patients under 13 receiving HPV vaccination increased substantially after the intervention. It is difficult to know if the difference was driven by the intervention versus an increase in in-person visits after the initial stages of the pandemic or other factors.

We did not assess vaccination hesitancy as part of this project however, hesitancy likely plays a significant role in under-vaccination. In a study by Rositch et al.Citation14 looking at reasons for HPV vaccination non-initiation in patients aged 13–17 years, 63% of parents were hesitant with the top reasons for hesitancy being: (1) safety concern/side effects, (2) lack of necessity, (3) reporting the adolescent is already up-to-date, (4) reporting the adolescent is not sexually active, and (5) lack of provider recommendation. In our evaluation, of those that were in clinic and did not receive the series, we cannot delineate if it was because vaccination was not offered or was declined by the parent and for what reason. Further investigations could look at HPV vaccination non-initiation for children aged 9 to 10 years to see if the parent reasons for hesitancy differ.

Past interventions have largely focused on improving acceptability of the HPV vaccine and reducing missed opportunities in clinic.Citation15,Citation16 While these approaches are clearly important, including in our system, our data suggest that when seen in clinic, most patients are more likely to be vaccinated. Of those not seen in clinic, improving access to vaccinations outside of traditional clinical settings may be more impactful given the low percent of patients in this age group that regularly seek care. These setting could include schools, dental clinics,Citation17 pharmacies, school-based health centersCitation18 and other community-based locations. Studies have also shown that initiation of HPV vaccines at a younger age increases likelihood of vaccine completion by age 13 years.Citation10

This QI project was easy to implement and aligned with current workflows in clinics. There was high acceptability to administrators, clinicians and staff as it aligned with organizational values. In addition, it did not require major EHR changes or process changes including no change to medical assistant workflow which includes assessing for vaccines at all in-person visits with EHR prompts. There was no need for significant parent/adolescent discussion outside of current best practice. Other studies have used similar interventions (EHR BPA changes for medical assistants) in quality improvement projects with excellent results.Citation19,Citation20

Barriers to implementation and uptake included high turn-over of staff and need for re-training. Perhaps more and sustained communication with providers and clinical staff would have led to higher uptake than what was seen. While most children eligible to receive HPV vaccine were vaccinated, 30–40% of eligible children presenting for in-patient visits were missed. It is possible that uptake was different for different specialties within DHHA (Pediatrics, Family Medicine, Pediatrics/Internal Medicine) which could account for the differences, but we did not account for specialty in our analyses.

Overall, it remains to be seen if completion rates for children by age 13 years old improve with time. Other studies with initiation at ages 9–10 do show increased completion with longer follow-up times.Citation21,Citation22 There was a notable decrease in the percentage of HPV vaccination (percent of missed opportunities) during in-person visits from September to December 2021, but overall post-implementation there was an increase in total numbers of HPV vaccine given. For context, the omicron variant surge started in December 2021 with a surge of both omicron and delta variants occurring in January 2022.Citation23,Citation24 We suspect that the increase in missed opportunities during this time period was due to pandemic-associated issues including vaccine refusal secondary to an increased number of sick visits and high staff turnover with many new staff forgetting to recommend HPV vaccination. It is possible that parents refused vaccination because of concern for the HPV vaccination at a young age but more likely other factors were involved.

Strengths of this evaluation include the ability to evaluate a large number of diverse patients 9–12 years old (inclusive) within an extensive community health system and the ease and acceptability of the intervention. This intervention could likely be replicated in other health systems including those in resource-limited settings.

There are some important limitations. We did not talk to patients or parents directly about the acceptability of HPV vaccination at a younger age or reasons some parents/guardians refused vaccination when it was offered. Because we only had a 14 month post-intervention period, we did not assess for completion after age 13. Although we did see an increase in completion rates even with a short post-intervention period it is not clear if this change is directly associated with the intervention versus an increase in in-person visits among empaneled patients during this time period.

Conclusion

A low-cost, pragmatic intervention to initiate HPV vaccination at 9 years of age had high uptake among patients less than 11 years of age and improved overall initation rates by age 13 years. It remains to be seen if initiation at first opportunity improves completion rates by age 13 years. Future studies should look at HPV vaccination completion rates as well as sustainability of the improvement of HPV vaccination initiation.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (610.8 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristin Breslin and Maria Casaverde for their contributions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2180971.

Additional information

Funding

References

- “HPV”. Centers for disease control and prevention. 2020 Sep 14. www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/protecting-patients.html.

- Senkomago V, Henley SJ, Thomas CC, Mix JM, Markowitz LE, Saraiya M. Human papillomavirus-attributable cancers - United States, 2012–2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 23;68(33):724–7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6833a3. PMID: 31437140; PMCID: PMC6705893.

- Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, Wang J, Roth A, Fang F, Sundström K, Dillner J, Sparén P. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1340–48. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1917338.

- Saraiya M, Unger ER, Thompson TD, Lynch CF, Hernandez BY, Lyu CW, Steinau M, Watson M, Wilkinson EJ, Hopenhayn C, et al. HPV typing of cancers workgroup. US assessment of HPV types in cancers: implications for current and 9-valent HPV vaccines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015 Apr 29;107(6):djv086. doi:10.1093/jnci/djv086. PMID: 25925419; PMCID: PMC4838063.

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination - updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Dec 16;65(49):1405–08. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6549a5. PMID: 27977643.

- Saslow D, Andrews KS, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Smith RA, Fontham ETH, The American Cancer Society Guideline Development Group. Human papillomavirus vaccination 2020 guideline update: American cancer society guideline adaptation. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(4): 274- 273. doi: 10.3322/caac.21616.

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Markowitz LE, Valier MR, Fredua B, Crowe SJ, Stokley S, Singleton JA. 2022. National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 71:1101–08. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7135a1.

- US Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. Adolescent health: summary and policy options. Washington (DC): US Government Printing Office. OTA-H-468; 1991.

- Immunizations for Adolescents. National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Immunizations for adolescents - NCQA. [ Accessed 2022 Oct 20].

- St Sauver JL, Rutten LJF, Ebbert JO, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Jacobson RM. Younger age at initiation of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination series is associated with higher rates of on-time completion. Prev Med. 2016 Aug;89:327–33. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.039. Epub 2016 Feb 28. PMID: 26930513; PMCID: PMC4969174.

- Brammer CA, Kimmins LM, Swanson R, Kuo J, Vranesich P, Jacques-Carroll LA, Shen AK. Decline in child vaccination coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic — Michigan Care Improvement Registry, May 2016–May 2020. MMWR. 2020;69(20):630–31. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6920e1.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Denver health: how a safety net system maximizes its value. AHRQ Pub No 19-0052-3. Published 2019. Updated 2019.[Accessed 2019 Dec 28]. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/lhs/lhs_case_studies_denver_health.pdf.

- Vaccines for Children Program (VFC). Centers for disease control and protection. VFC: Vaccines for Children Program | CDC. [Accessed 2022 Oct 20].

- Rositch A, Liu T, Chao C, Moran M, Beavis A. Levels of parental human papillomavirus vaccine hesitancy and their reasons for not intending to vaccinate: insights from the 2019 National Immunization Survey -Teen. J Adolesc Health. 2022 Mar 9;71(1):39–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.01.223.

- Cataldi JR, O’leary ST, Markowitz LE, Allison MA, Crane LA, Hurley LP, Brtnikova M, Beaty BL, Gorman C, Meites E, et al. Changes in strength of recommendation and perceived barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination: longitudinal analysis of primary care physicians, 2008–2018. J Pediatr. 2021 Jul;234:149–57.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.03.002. Epub 2021 Mar 6. PMID: 33689710.

- Rand CM, Tyrrell H, Wallace-Brodeur R, Goldstein NPN, Darden PM, Humiston SG, Albertin CS, Stratbucker W, Schaffer SJ, Davis W, et al. A learning collaborative model to improve human papillomavirus vaccination rates in primary care. Acad Pediatr. 2018 Mar;18(2S):S46–52. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2018.01.003. PMID: 29502638.

- Daley EM, Vamos CA, Thompson E, Vázquez-Otero C, Griner SB, Merrell L, Kline N, Walker K, Driscoll A, Petrila J. The role of dental providers in preventing HPV-related diseases: a systems perspective. J Dent Educ. 2019 Feb;83(2):161–72. doi:10.21815/JDE.019.019. PMID: 30709991.

- Munn MS, Kay M, Page LC, Duchin JS Completion of the human papillomavirus vaccination series among adolescent users and nonusers of school-based health centers. Public Health Rep. 2019 Sep/Oct;134(5):559–66. doi:10.1177/0033354919867734. Epub 2019 Aug 12. PMID: 31404508; PMCID: PMC6852067.

- Tomcho MM, Lou Y, O’leary SC, Rinehart DJ, Thomas-Gale T, Penny L, Frost HM. Closing the equity gap: an intervention to improve chlamydia and gonorrhea testing for adolescents and young adults in primary care. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13(2022):21501319221131382. doi:10.1177/21501319221131382.

- Implementation of the connect for health pediatric weight management program: study protocol and baseline characteristics

- Simione M, Farrar-Muir H, Mini FN, Perkins ME, Luo M, Frost H, Orav J, Metlay J, Ah Z, Kistin CJ, et al. Implementation of the connect for health pediatric weight management program: study protocol and baseline characteristics. J Comp Eff Res. 2021;10(11):881–92. doi:10.2217/cer-2021-0076.

- Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Talluri R, Wonodi C, Shete S. Trends in HPV vaccination initiation and completion within ages 9–12 years: 2008-2018. Pediatrics. 2021 Jun;147(6):e2020012765. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-012765. Epub 2021 May 3. PMID: 33941585; PMCID: PMC8785751.

- Ferrara P, Dallagiacoma G, Alberti F, Gentile L, Bertuccio P, Odone A. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer: a systematic review of the impact of COVID-19 on patient care. Prev Med. 2022 Nov;164:107264. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107264. Epub 2022 Sep 20. PMID: 36150446; PMCID: PMC9487163.

- CDC museum COVID-19 timeline | David J. Sencer CDC museum | CDC. [Accessed 2022 Dec 22].