ABSTRACT

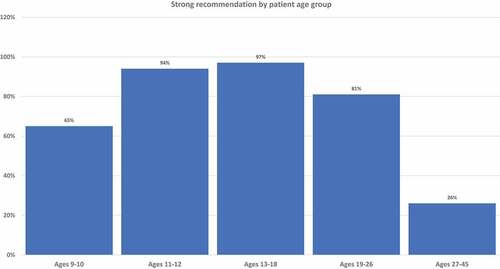

Clinician recommendation remains a critical factor in improving HPV vaccine uptake. Clinicians practicing in federally qualified health centers were surveyed between October 2021 and July 2022. Clinicians were asked how they recommended HPV vaccination for patients aged 9–10, 11–12, 13–18, 19–26, and 27–45 y (strongly recommend, offer but do not recommend strongly, discuss only if the patient initiates the conversation, or recommend against). Descriptive statistics were assessed, and exact binomial logistic regression analyses were utilized to examine factors associated with HPV vaccination recommendation in 9–10-y-old patients. Respondents (n = 148) were primarily female (85%), between the ages of 30–39 (38%), white, non-Hispanic (62%), advanced practice providers (55%), family medicine specialty (70%), and practicing in the Northeast (63%). Strong recommendations for HPV vaccination varied by age: 65% strongly recommended for ages 9–10, 94% for ages 11–12, 96% for ages 13–18, 82% for age 19–26, and 26% for ages 27–45 y. Compared to Women’s Health/OBGYN specialty, family medicine clinicians were less likely to recommend HPV vaccination at ages 9–10 (p = .03). Approximately two-thirds of clinicians practicing in federally qualified health centers or safety net settings strongly recommend HPV vaccine series initiation at ages 9–10. Additional research is needed to improve recommendations in younger age groups.

Introduction

Oncogenic HPV infections cause oropharyngeal, cervical, anal, penile, vulvar, and vaginal cancers.Citation1 Data demonstrate reduction in oncogenic HPV infections, precancers, and cancers among vaccinated individuals.Citation2–6 Immunity appears highly durable, with no evidence of waning of protection over more than a decade of follow-up.Citation7,Citation8 In addition, data indicate that vaccination at younger ages is more effective than in the later teen years.Citation5,Citation9–11 Taken together, these data indicate that HPV vaccination of all adolescents prior to HPV exposure has the potential to prevent over 40,000 cancers in the United States each year.Citation12,Citation13

HPV vaccination has been routinely recommended for adolescent females since 2007Citation14 and for adolescent males since 2011.Citation15 The most recent guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), published in 2019, allow vaccination beginning at age 9, recommend routine vaccination at ages 11–12, recommend catch-up vaccination at ages 13–26, and recommend shared clinical decision-making for individuals aged 27–45.Citation16

However, coverage with at least one dose of HPV vaccine in the United States remains approximately 20% points lower than coverage with other adolescent vaccines, and only half of adolescents complete the HPV vaccine series by the recommended age of 13.Citation17 Due to persistent coverage gapsCitation17 and data indicating that initiating the HPV vaccine series at age 9 improved on-time completion,Citation18–22 the American Academy of PediatricsCitation23 and the American Cancer SocietyCitation24 both revised their recommendations to begin routine recommendation of the HPV vaccine series starting at age 9. The American Academy of Pediatrics and American Cancer Society statements are consistent with 2019 recommendations from the CDC,Citation16 but go further by including a routine recommendation for ages 9 and 10 rather than a permissive recommendation.

The majority of literature has focused on HPV vaccination at ages 11 and older,Citation25–28 with fewer studies examining attitudes toward and acceptability of HPV vaccination beginning at age 9. A qualitative study indicated that both parents and clinicians found HPV vaccine initiation at age 9 to be acceptable to parents, and clinicians found discussions to be straightforward and productive.Citation29 A national survey conducted in February–March 2021 found that approximately 20% of clinicians recommend HPV vaccination age ages 9–10.Citation30 However, little is known about clinician recommendation in safety net settings that often serve patients at the highest risk of future cervical cancer development. This study describes HPV vaccine recommendation practices among clinicians practicing in federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and other safety net settings.

Methods

Participant recruitment

Between October 2021 and July 2022, clinicians were recruited through periodic recruitment messages via the American Cancer Society Vaccinating Adolescents Against Cancer (VACs) program, and the professional networks of authors (RP, SV). This paper reports a sub-analysis of a cross-sectional survey which focused on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on cervical cancer screening. Clinicians were eligible to participate if they: 1) performed cervical cancer screening and 2) were currently practicing in an FQHC or safety net facility in the United States. This study was approved by Moffitt Cancer Center’s Scientific Review Committee and then reviewed by an Institutional Review Board who determined the study was exempt (MCC #20048).

Survey content and study variables

Survey items were developed based on a review of recent literature exploring the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer screening practices,Citation31,Citation32 the investigators’ clinical observations, and input of an eight-member Advisory Board including clinicians, researchers, subject matter experts, and public health experts. The draft survey was subsequently reviewed by a panel of FQHC providers who perform cervical cancer screening (n = 8), refined based on their feedback, piloted with a small group of FQHC providers identified through the networks of the authors (RP, SV), further revised, and finalized.

Clinician sociodemographic characteristics

Clinician sociodemographic characteristics included age categories; gender identity; race, and ethnicity. Medical training was assessed as physician or advanced practice providers (APP), which included physician assistants (PA), nurse practitioners (NP), and certified nurse midwives (CNM). Medical specialty included obstetrics and gynecology (OBGYN), family medicine, internal medicine, pediatric/adolescent medicine, and women’s health. Clinician training variables included: (1) MD and DO and (2) APPs: NPs, CNMs, PAs, others. Based on prior research indicating the effect of specialty on HPV vaccination,Citation33 the Clinician Specialty variable included: (1) women’s health and OBGYN, (2) Family medicine, and (3) internal medicine, pediatric/adolescent medicine, and other. Geographic locations included four US regions (northeast, south, midwest, and west) and a non-responder category for those who did not provide state or zip code. Based on national data indicating geographic variation in coverage rates by the US regionCitation17 as well and distribution of respondents, the region was categorized as Northeast, South, and all others (West & Midwest).

Outcome of interest: HPV recommendation by age

Participants were asked how they recommend HPV vaccines for each of the following age groups: ages 9–10, 11–12, 13–18, 19–26, and 27–45 y. Based on other national surveys,Citation34 response options included: “strong recommendation,” “offer but do not recommend strongly,” “recommend against,” “do not discuss unless patient brings it up,” “I do not see this age range in my practice.”

Analytic plan

We utilized descriptive statistics (frequencies/percentages) to assess clinician characteristics and outcome variables. Due to small cell sizes, exact binary logistic regression analysis was utilized to examine factors associated with clinician HPV vaccination recommendation in 9–10-y-olds. Age, gender, race/ethnicity, region, and clinician type were included as covariates in the regression model. Due to limited numbers, we categorized race/ethnicity as white non-Hispanic versus all others. We had only one transgender participant, which precluded inclusion of transgender as a variable in regression models. To avoid excluding their data, they were included with “female” in the analysis because 85% of the sample identified as female; analysis categorizing this participant as “male” yielded similar results. Manual forward selection was used with a significance level for entry of 0.10. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4.

Results

Physician sample

Our sample of 148 clinicians was primarily female (85%), between the ages of 30–39 (38%), white, non-Hispanic (62%), were APPs (NP, CNM, PA) (55%), and were family medicine clinicians (70%), and practiced in the Northeast (63%). We excluded clinicians who reported that they did not see patients within each relevant age group from both percentages of recommendation strength and from regression analyses. details clinician and practice characteristics.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants.

HPV vaccination recommendation practices

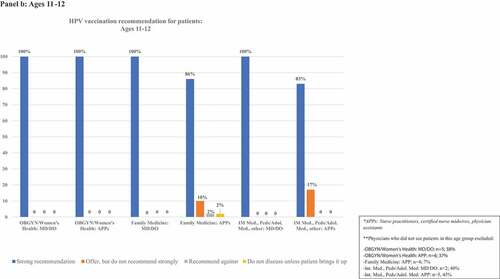

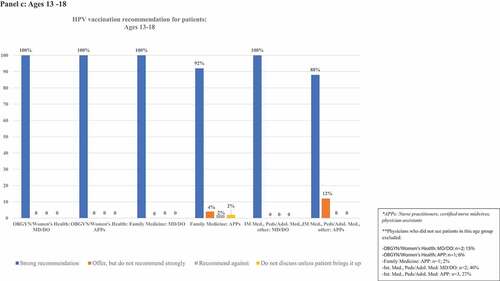

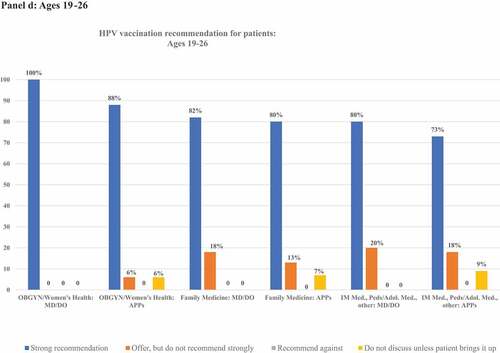

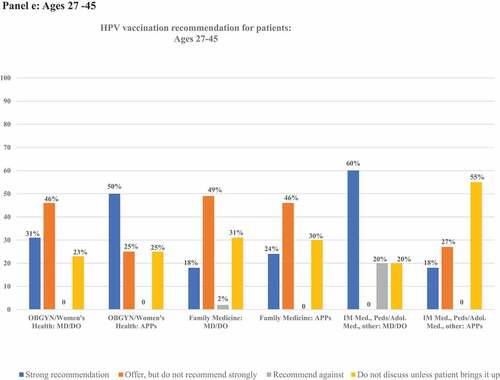

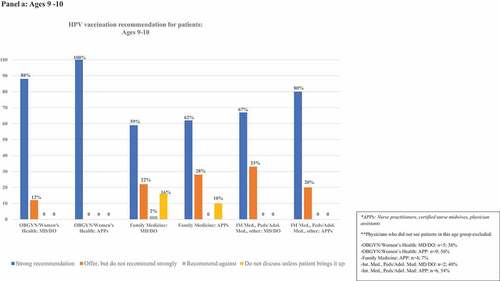

details frequencies of HPV vaccination recommendation practices in each age group. illustrates rates of strong recommendation by age overall, and illustrates recommendation strength for each age group for each subcategory of clinician specialty and training.

Figure 1. Proportion of clinicians giving strong recommendations for HPV vaccination at each age group. Clinicians who do not see patients in each age group are excluded from denominators.

Figure 2. Proportion of clinicians giving strong recommendations for HPV vaccination at each age group, categorized by clinician specialty and training. Panels describe recommendation practices for patients aged 9–10 y (panel A), 11–12 y (panel B), 13–18 y (panel C), 19–26 y (panel D), and 27–45 y (panel E). Clinicians who do not see patients in each age group are excluded from denominators and noted in footnotes.

Table 2. Clinician HPV vaccination recommendation practices by age.

Ages 9–10

Eighty-two percent (n = 122) of respondents saw patients aged 9–10 y. Among these, 65% (n = 80) indicated they strongly recommend HPV vaccination to patients aged 9–10 y, 23% (n = 28) offered, but do not strongly recommend it, 11% (n = 13) did not discuss the vaccine unless the patient/family brings it up, and one clinician recommended against HPV vaccination. Recommendations varied by clinician type. Among OBGYN/Women’s Health clinicians, 62% of MD/DOs and 44% of APPs saw 9–10-y-old patients. Of those who saw 9–10-y-old patients, 88% of MD/DOs and 100% of APPs strongly recommended HPV vaccination. In contrast, nearly all Family Medicine clinicians saw this age group, but strong recommendations were given by only 59% and 62% of the Family Medicine MD/DOs and APPs, respectively. Approximately half of clinicians in other specialties saw patients in this age group, and strong recommendations were given by 67% of MD/DOs and 80% of APPs.

Ages 11–12

Eighty-five percent (n = 126) of respondents saw patients aged 11–12 y. Among these, 94% (n = 118) strongly recommended vaccination, while 5% (n = 6) offered, but did not strongly recommend it. One clinician indicated they do not discuss the vaccine unless the patient/family brings it up and one recommended against vaccination. Among OBGYN/Women’s Health clinicians, 62% of MD/DOs and 63% of APPs saw 11–12-y-old patients. Of those who saw 11–12-y-old patients, 100% of both MD/DOs and APPs strongly recommended HPV vaccination. Nearly all Family Medicine clinicians saw this age group, and strong recommendations were given by 100% of MD/DOs and 86% of APPs. Approximately half of clinicians in other specialties saw patients in this age group, and strong recommendations were given by 100% of MD/DOs and 83% of APPs.

Ages 13–18

Ninety-four percent (n = 139) of respondents saw patients aged 13–18 y. Among these, 96% (n = 134) strongly recommended vaccination in this age group, and 2% (n = 3) offered, but did not strongly recommend it. One clinician did not discuss the vaccine unless the patient/family brings it up, and one recommended against vaccination. Among OBGYN/Women’s Health clinicians, 85% of MD/DOs and 94% of APPs saw 13–18-y-old patients. Of those who saw 13–18-y-old patients, 100% of both MD/DOs and APPs strongly recommended HPV vaccination. Nearly all Family Medicine clinicians saw this age group, and strong recommendations were given by 100% of MD/DOs and 92% APPs. More than half of clinicians in other specialties saw patients in this age group, and strong recommendations were given by 100% of MD/DOs and 88% of APPs.

Ages 19–26

All respondents saw patients in this age group. Most clinicians (82%, n = 122) indicated they strongly recommend HPV vaccine to patients aged 19–26 y, 14% (n = 20) offered, but did not strongly recommend the vaccine, and 4% (n = 6) did not discuss it unless the patient/family brings it up. No clinicians recommended against vaccination in this age group. Among OBGYN/Women’s Health clinicians, 100% of MD/DOs and 88% of APPs strongly recommended HPV vaccination. Among Family Medicine clinicians, 82% of MD/DOs and 80% of APPs strongly recommended HPV vaccination. Among clinicians of other specialties, 80% of MD/DOs and 73% of APPs strongly recommended HPV vaccination.

Ages 27–45

All respondents saw patients in this age group. Among these, 26% (n = 39) provided a strong recommendation for HPV vaccine in this age group, 41% (n = 62) offered, but did not strongly recommend it, and 30% (n = 45) did not discuss it unless the patient/family brings it up. Two clinicians recommended against HPV vaccination in this age group. Among OBGYN/Women’s Health clinicians, 31% of MD/DOs and 50% of APPs strongly recommended HPV vaccination. Among Family Medicine clinicians, 18% of MD/DOs and 24% of APPs strongly recommended HPV vaccination. Among clinicians of other specialties, 60% of MD/DOs and 18% of APPs strongly recommended HPV vaccination.

Factors associated with HPV vaccination recommendation

details logistic regression model results for clinician and practice characteristics associated with odds of HPV vaccination recommendation in 9–10-y-old patients. Race/ethnicity, age, region, and gender were all subsequently dropped from the model in logistic regression analyses as p > .10. Clinician specialty was significantly associated with odds of HPV vaccination recommendation in 9–10-y-olds (p = .088). Compared to clinicians representing the Women’s Health/OBGYN specialty, family medicine clinicians were less likely to report that they strongly recommend HPV vaccination to their 9–10-y-old patients (OR = 0.11, 95% CI: .014–.869, p = .0364).

Table 3. Final model of clinician and practice characteristics associated with odds of reporting strong recommendation for patients aged 9–10 y old. Using manual forward selection, the following variables sequentially fell out of the model (p > .10): 1) race/ethnicity 2) age 3) region, and 4) gender.

Discussion

This study indicates high overall support for HPV vaccination among this cohort of clinicians practicing in federally qualified health centers or safety net settings. Two-thirds of clinicians strongly recommended HPV vaccination for patients ages 9–10, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society.Citation23,Citation24 Nearly all clinicians strongly recommended HPV vaccination at ages 11–18, the ages for which recommendations are harmonized among all organizations and also universally paid for by the Vaccines for Children program.Citation35 Approximately 70% of clinicians were following guidelines for patients aged 27–45, either offering but not strongly recommending HPV vaccination or allowing patient to lead discussions, consistent with CDC recommendations for shared clinical decision-making with patients when deemed appropriate.Citation16

Strong provider recommendation has overwhelmingly been demonstrated as the most important factor associated with HPV vaccination acceptance in the literature.Citation28,Citation36–38 Yet, a systematic review of studies published between 2012 and 2019 identified age, geographic, socioeconomic, and racial disparities in HPV vaccination recommendation, with fewer recommendations for patients who were younger, living in the South, nonwhite, low-income, or uninsured.Citation27 Prior national surveys indicated increasing rates of provider recommendation among 11–12-y-olds from 35% in 2009 to 40% in 2011Citation39 to 59% in 2021.Citation30 Recommendations appear to vary by populations sampled: a 2018 study of members of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians found higher rates of strong HPV vaccine recommendations at ages 11–12: 84% for pediatricians and 69% for family medicine physicians.Citation34 In this study, 94% of clinicians strongly recommended vaccination at ages 11–12.

Few studies have examined recommendations at ages 9–10. The most recent national survey, conducted in February–March 2021, found that only 20% of clinicians routinely recommended HPV vaccination at ages 9–10.Citation30 Our finding that 65% of clinicians surveyed strongly recommended HPV vaccination at ages 9–10 could be due to several factors, including greater promotion by the American Academy of Pediatrics and American Cancer Society during the April–August 2021 “back to school” vaccination period (after the prior survey was completed) or different distributions of respondents by specialty, region, and practice type. In addition, clinicians who practice in safety net settings may have more positive attitudes toward vaccination. HPV vaccination rates have been and remain higher among adolescents living below the poverty line in the United States,Citation17 many of whom receive care at in safety net settings. Research has also shown positive associations between clinician HPV vaccine recommendation and practices with higher proportions of Black and Hispanic patients and Vaccines for Children (publicly subsidized) vaccine insurance coverage.Citation40 High rates of strong recommendations at all ages in this study may also stem from higher awareness of the burden of HPV-related diseases and cervical cancer among clinicians who provide both vaccination and cancer screening. Prior research demonstrates an association between knowledge and vaccine recommendation.Citation40 Research spanning more than a decade has demonstrated an association between clinician comfort discussing sexually transmitted infections and vaccine recommendations,Citation25,Citation26,Citation41 and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advocates strong recommendations for HPV vaccination by its members.Citation42 Our results supported this: though only approximately half of OBGYN/Women’s Health clinicians saw patients aged 9–10 y, they had higher rates of strong recommendations for HPV vaccination than family medicine clinicians. Recommending vaccination at ages 9–10 may be also be encouraged by clinicians’ positive experiences. A 2020 qualitative study found high parental acceptance of HPV vaccination at ages 9–10. Providers attributed vaccine acceptability to reduced stigma related to sexual activity and the need for fewer shots per visit.Citation25

Recommending HPV vaccination at ages 9–10 may provide a way to close the gap between HPV vaccination coverage and coverage with other adolescent vaccines.Citation19,Citation20,Citation29 Several studies indicate up to twofold higher rates of HPV vaccine series completion when the series is initiated at ages 9–10.Citation19–21,Citation43 In addition, longitudinal studies with four to 10 y of follow-up show that initiating vaccination at ages 9–10 can lead to year-over-year improvement of vaccine completion by age 13 over an entire clinic population.Citation18,Citation44

A strength of our study is its focus on FQHCs, who care for patients at highest risk of cervical cancer. This study, however, also has limitations. Due to the limited scope of the project, we aimed to recruit only 150 respondents, which limits our ability to statistically identify associations between provider characteristics and HPV vaccine recommendations, as well as explore recommendation practices by males, pediatricians, and clinicians from race/ethnicities other than white/non-Hispanic, and those affiliated with academic medical centers. We recruited our sample via FQHC networks, therefore, while national in scope, it is not a nationally representative sample and we were unable to calculate a response rate. The project was targeted to clinicians who provide cervical cancer screening, which limited the number of pediatricians. Prior literature indicates that pediatricians are more likely to recommend HPV vaccine than family medicine physicians.Citation30,Citation34 The attitudes of clinicians who both provide vaccination and screening may differ from the group of clinicians who provide HPV vaccination in the pediatric setting only. It is possible that this group of family medicine clinicians who provide cervical cancer screening may have more positive attitudes toward HPV vaccination than the general population of family medicine clinicians. Finally, those who responded to the survey may have more experience with the burden of HPV disease and cervical cancers than the general clinician population. In addition, this study did not include qualitative data to explain the quantitative findings. Future research should explore reasons for lower recommendation rates by clinicians at ages 9–10, describe why a small number of clinicians do not discuss HPV vaccination, and examine parental attitudes toward vaccination at ages 9–10 to provide guidance for strategies to improve recommendation rates.

Conclusions

In this study of clinicians practicing at FQHCs and safety-net settings, approximately two-thirds of clinicians strongly recommended HPV vaccination at ages 9–10. While this is higher than prior studies, respondents reported >90% strong recommendation to older adolescent age groups. Our findings suggest the need for additional research to improve provider recommendations based on the updated guidance of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society for routine vaccine initiation at age 9.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- IARC. Cervical cancer screening IARC handbooks of cancer prevention volume 18. Published online 2022 [accessed 2022 Dec 23]. https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Handbooks-Of-Cancer-Prevention/Cervical-Cancer-Screening-2022.

- Brown DR, Kjaer SK, Sigurdsson K, Iversen O-E, Hernandez‐avila M, Wheeler C, Perez G, Koutsky L, Tay E, Garcia P, et al. The impact of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV; types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine on infection and disease due to oncogenic nonvaccine HPV types in generally HPV-naive women aged 16–26 years. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(7):926–9. doi:10.1086/597307.

- Mix JM, Van Dyne EA, Saraiya M, Hallowell BD, Thomas CC. Assessing impact of HPV vaccination on cervical cancer incidence among women aged 15-29 years in the United States, 1999-2017: an ecologic study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2021;30(1):30–37. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-0846.

- Brisson M, Bénard É, Drolet M, Bogaards JA, Baussano I, Vänskä S, Jit M, Boily M-C, Smith MA, Berkhof J, et al. Population-level impact, herd immunity, and elimination after human papillomavirus vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis of predictions from transmission-dynamic models. Lancet Public Health. 2016;1(1):e8–17. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(16)30001-9.

- Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, Wang J, Roth A, Fang F, Sundström K, Dillner J, Sparén P. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1340–48. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917338.

- Arbyn M, Bryant A, Beutels P, PPL Martin-Hirsch, E Paraskevaidis, E Van Hoof, M Steben, Y Qiao, FH Zhao, A Schneider, A Kaufmann, J Dillner, L Markowitz, A Hildesheim. Prophylactic vaccination against human papillomaviruses to prevent cervical cancer and its precursors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011(4):CD009069. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009069.

- Kjaer SK, Nygård M, Dillner J, Brooke Marshall J, Radley D, Li M, Munk C, Hansen BT, Sigurdardottir LG, Hortlund M, et al. A 12-year follow-up on the long-term effectiveness of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in 4 Nordic countries. Clin Infect Dis off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2018;66(3):339–45. doi:10.1093/cid/cix797.

- Porras C, Tsang SH, Herrero R, Guillén D, Darragh TM, Stoler MH, Hildesheim A, Wagner S, Boland J, Lowy DR, et al. Efficacy of the bivalent HPV vaccine against HPV 16/18-associated precancer: long-term follow-up results from the Costa Rica vaccine trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(12):1643–52. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30524-6.

- Falcaro M, Castañon A, Ndlela B, Checchi M, Soldan K, Lopez-Bernal J, Elliss-Brookes L, Sasieni P. The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: a register-based observational study. Lancet Lond Engl. 2021;398(10316):2084–92. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02178-4.

- Gertig DM, Brotherton JM, Budd AC, Drennan K, Chappell G, Saville AM. Impact of a population-based HPV vaccination program on cervical abnormalities: a data linkage study. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):227. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-227.

- Perkins RB, Lin M, Wallington SF, Hanchate A. Impact of number of human papillomavirus vaccine doses on genital warts diagnoses among a national cohort of U.S. adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(6):365–70. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000615.

- Senkomago V, Henley SJ, Thomas CC, Mix JM, Markowitz LE, Saraiya M. Human papillomavirus-attributable cancers - United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(33):724–28. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6833a3.

- Saraiya M, Unger ER, Thompson TD, Lynch CF, Hernandez BY, Lyu CW, Steinau M, Watson M, Wilkinson EJ, Hopenhayn C, et al. US assessment of HPV types in cancers: implications for current and 9-valent HPV vaccines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(6):djv086. doi:10.1093/jnci/djv086.

- ACIP. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56. (No RR-2).

- ACIP. Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males–Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(50):1705–08.

- Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, Unger ER, Romero JR, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):698–702. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a3.

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Markowitz LE, Valier MR, Fredua B, Crowe SJ, Stokley S, Singleton JA. National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — national immunization survey-teen, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(35):1101–08. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7135a1.

- Casey SM, Jansen E, Drainoni ML, Schuch TJ, Leschly KS, Perkins RB. Long-term multilevel intervention impact on human papillomavirus vaccination rates spanning the COVID-19 pandemic. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2022;26(1):13–19. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000648.

- Perkins RB, Legler A, Jansen E, Bernstein J, Pierre-Joseph N, Eun TJ, Biancarelli DL, Schuch TJ, Leschly K, Fenton ATHR, et al. Improving HPV vaccination rates: a stepped-wedge randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1). doi:10.1542/peds.2019-2737.

- Goleman MJ, Dolce M, Morack J. Quality improvement initiative to improve human papillomavirus vaccine initiation at 9 years of age. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(7):769–75. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2018.05.005.

- St Sauver JL, Rutten LJF, Ebbert JO, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Jacobson RM. Younger age at initiation of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination series is associated with higher rates of on-time completion. Prev Med. 2016;89:327–33. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.039.

- Cox JE, Bogart LM, Elliott MN, Starmer AJ, Meleedy-Rey P, Goggin K, Banerjee T, Samuels RC, Hahn PD, Epee-Bounya A, et al. Improving HPV vaccination rates in a racially and ethnically diverse pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2022;150(4):e2021054186. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-054186.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on. Why AAP recommends initiating HPV vaccination as early as age 9. Published online 2019 [accessed 2022 Sep 28]. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/14942?autologincheck=redirected?nfToken=00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000.

- American Cancer Society. ACS updates HPV vaccination recommendations to start at age 9. Published online 2020 [accessed 2022 Sep 28]. https://www.cancer.org/latest-news/acs-updates-hpv-vaccination-recommendations-to-start-at-age-9.html.

- Gilkey MB, McRee AL. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12(6):1454–68. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1129090.

- Lin C, Mullen J, Smith D, Kotarba M, Kaplan SJ, Tu P. Healthcare providers’ vaccine perceptions, hesitancy, and recommendation to patients: a systematic review. Vaccines. 2021;9(7):713. doi:10.3390/vaccines9070713.

- Kong WY, Bustamante G, Pallotto IK, Margolis MA, Carlson R, McRee A-L, Gilkey MB. Disparities in healthcare providers’ recommendation of HPV vaccination for U.S. adolescents: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2021;30(11):1981–92. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-21-0733.

- Constable C, Ferguson K, Nicholson J, Quinn GP. Clinician communication strategies associated with increased uptake of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: a systematic review. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(6):561–69. doi:10.3322/caac.21753.

- Biancarelli DL, Drainoni ML, Perkins RB. Provider experience recommending HPV vaccination before age 11 years. J Pediatr. Published online 2019 Nov 19;217:92–97. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.10.025.

- Kong WY, Huang Q, Thompson P, Grabert BK, Brewer NT, Gilkey MB. Recommending human papillomavirus vaccination at age 9: a national survey of primary care professionals. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(4):573–80. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2022.01.008.

- Miller MJ, Xu L, Qin J, Hahn EE, Ngo-Metzger Q, Mittman B, Tewari D, Hodeib M, Wride P, Saraiya M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on cervical cancer screening rates among women aged 21–65 years in a large integrated health care system — Southern California, January 1–September 30, 2019, and January 1–September 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(4):109–13. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7004a1.

- Wentzensen N, Clarke MA, Perkins RB. Impact of COVID-19 on cervical cancer screening: challenges and opportunities to improving resilience and reduce disparities. Prev Med. 2021;151:106596. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106596.

- Brennan LP, Rodriguez NM, Head KJ, Zimet GD, Kasting ML. Obstetrician/Gynecologists’ HPV vaccination recommendations among women and girls 26 and younger. Prev Med Rep. 2022;27:101772. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101772.

- Kempe A, O’leary ST, Markowitz LE, Crane LA, Hurley LP, Brtnikova M, Beaty BL, Meites E, Stokley S, Lindley MC. HPV vaccine delivery practices by primary care physicians. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20191475. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-1475.

- CDC. Vaccines for children program. Published 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/index.html.

- Fenton AT, Eun TJ, Clark JA, Perkins RB. Indicated or elective? The association of providers’ words with HPV vaccine receipt. Hum Vaccines Immunother. Published online 2018 May 30 ;1–7. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1480237.

- Eun TJ, Hanchate A, Fenton AT, et al. Relative contributions of parental intention and provider recommendation style to HPV and meningococcal vaccine receipt. Hum Vaccines Immunother. Published online 2019 Mar 12;1–6. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1591138.

- Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: the impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine. 2016;34(9):1187–92. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.023.

- Vadaparampil ST, Malo TL, Kahn JA, Salmon DA, Lee J-H, Quinn GP, Roetzheim RG, Bruder KL, Proveaux TM, Zhao X, et al. Physicians’ human papillomavirus vaccine recommendations, 2009 and 2011. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(1):80–84. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.009.

- Btoush R, Kohler RK, Carmody DP, Hudson SV, Tsui J. Factors that influence healthcare provider recommendation of HPV vaccination. Am J Health Promot AJHP. 2022;36(7):1152–61. doi:10.1177/08901171221091438.

- Bynum SA, Staras SAS, Malo TL, Giuliano AR, Shenkman E, Vadaparampil ST. Factors associated with Medicaid providers’ recommendation of the HPV vaccine to low-income adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2014;54(2):190–96. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.006.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Adolescent Health Care; and Immunization, Infectious Disease, and Public Health Preparedness Expert Work Group. Human papillomavirus vaccination: ACOG committee opinion, number 809. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(2):e15–21. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004000.

- Kashani BM, Tibbits M, Potter RC, Gofin R, Westman L, Watanabe-Galloway S. Human papillomavirus vaccination trends, barriers, and promotion methods among American Indian/Alaska Native and non-Hispanic white adolescents in Michigan 2006-2015. J Community Health. 2019;44(3):436–43. doi:10.1007/s10900-018-00615-4.

- Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Talluri R, Wonodi C, Shete S. Trends in HPV vaccination initiation and completion within ages 9-12 years: 2008-2018. Pediatrics. 2021;147(6):e2020012765. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-012765.