ABSTRACT

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has wreaked havoc across the globe for approximately three years. Vaccination is a key factor to ending this pandemic, but its protective effect diminishes over time. A second booster dose at the right time is needed. To explore the willingness to receive the fourth dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and its influencing factors, we commenced a national, cross-sectional and anonymous survey in mainland China among people aged 18 and above from October 24 to November 7, 2022. A total of 3,224 respondents were eventually included. The acceptance rate of the fourth dose was 81.1% (95% CI: 79.8–82.5%), while it was 72.6% (95% CI: 71.1–74.2%) for a heterologous booster. Confidence in current domestic situation and the effectiveness of previous vaccinations, and uncertainty about extra protection were the main reasons for vaccine hesitancy. Perceived benefit (aOR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.159–1.40) and cues to action (aOR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.60–1.88) were positively associated with the vaccine acceptance, whereas perceived barriers (aOR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.72–0.84) and self-efficacy (aOR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.71–0.89) were both negatively associated with it. Additionally, sex, age, COVID-19 vaccination history, time for social media, and satisfaction with the government’s response to COVID-19 were also factors affecting vaccination intention. Factors influencing the intention of heterologous booster were similar to the above results. It is of profound theoretical and practical significance to clarify the population’s willingness to vaccinate in advance and explore the relevant influencing factors for the subsequent development and promotion of the fourth-dose vaccination strategies.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has wreaked havoc across the globe for approximately three years. As of February 5, 2023, there have been more than 671.6 million confirmed cases and 6.8 million deaths caused by COVID-19.Citation1 After December 2021, the number of confirmed cases and deaths worldwide continues to rise markedly with the emergence of the Omicron (B1.1.519) variant and its subvariants.Citation1,Citation2 It has been well documented that the Omicron variant carries multiple spike mutations with higher transmissibility and ability to evade natural infection-induced or vaccine-induced immunity than previous variants.Citation3 Despite the availability of several oral antivirals, including azvudine and favipiravir, vaccination is still considered to be an essential and effective way to prevent poor prognosis.Citation4–6 In response to those challenges and to reduce the burden on the healthcare system, Israeli authorities approved the fourth dose of BNT162b2 on 2 January, 2022 for people aged 60 years or older, healthcare workers, and other high-risk groups.Citation7 Chile, France, Italy, the United Kingdom, the United States, Singapore, and other countries also subsequently started to implement fourth-dose vaccination strategies.Citation8–10 According to the WHO weekly report released on October 26, 2022,Citation11 16 studies conducted among long-term care facility residents, older adults, healthcare workers, and adults have assessed the relative vaccine effectiveness of a second booster dose of mRNA vaccines.Citation11 Compared with the third dose, the fourth dose of COVID-19 vaccine provided improved protection against infection, symptomatic disease, and severe outcomes during an omicron-dominant period, although the duration of protection remains unknown.Citation11–13

The local epidemic in China has recently shown a complex situation with widespread and multiple transmission chains.Citation14 Undoubtedly, building a strong and robust immune barrier is the key to ending COVID-19. As of November 11, 2022, approximately 892.9 million people have received their first booster vaccination in China, including 46.7 million people who received a heterologous booster dose.Citation15 Heterologous booster refers to the use of vaccines with different technical routes for the purpose of complementing advantages and avoiding adverse effects.Citation16,Citation17 Deng et al. showed higher geometric mean titers (GMTs) of neutralizing antibodies against different SARS-CoV-2 variants and better efficacy in the heterologous booster group.Citation18 In addition, inhaled aerosolized Ad5 COVID-19 vaccine followed by two doses of inactivated vaccine may induce higher neutralizing antibody levels against Omicron variant BA.5.Citation16 Its use in existing vaccine regimens in China exhibits significant potential for preventing emerging Omicron-induced pandemic waves. A second booster dose at the right time is needed to end the COVID-19 pandemic.Citation14 Although widespread vaccination of the fourth dose has not yet begun globally before we conducted this survey, especially for the whole population, we believe it is of profound theoretical and practical significance to clarify the population’s willingness to vaccinate in advance and explore the relevant influencing factors for the subsequent development and promotion of the fourth dose vaccination strategies.Citation7–9,Citation14

Mainly constituted by individual health beliefs (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived barriers, and perceived benefit), cues to action, self-efficacy and demographic characteristics, the health belief model (HBM) is a long-established and traditional health education model.Citation19–24 It has been widely used to predict and explain the acceptance of vaccines against COVID-19, measles, human papillomavirus, etc., and influencing factors among different populations in recent years.Citation25–30 Given the urgency of the current global epidemic and the recurrence of outbreaks, it is worth considering the implementation of the fourth dose in advance. Therefore, we conducted an anonymous survey in mainland China based on the HBM in the whole population, with the aim of providing basic data to support the rapid adjustment and implementation of vaccination strategies in China and other countries.

Methods

Study design and data collection

From October 24, 2022 to November 7, 2022, we conducted a national, cross-sectional and anonymous survey among Chinese adults via an online platform called Wen Juan Xing (Changsha Ranxing Information Technology Co., Ltd., Hunan, China). As one of the largest data science companies in China, it has a professional sample database covering more than 6.2 million respondents with multiple attributes (age, sex, location, occupation, etc.) and quality control conditions to accurately facilitate the target population for research purposes. A random stratified sampling method was used to match the relative proportion of the population of 31 provinces with the Seventh National Population Census.Citation31 Chinese residents aged 18 years and above were the target population. If the target individual cannot respond within one day, another random selection will be conducted until the expected sample size is obtained.

Sample size

We used PASS software 15.0 (NCSS LLC., Kaysville, U.T., USA) to calculate the sample size with a series of preset parameters in advance. The acceptance rate (p) ranged from 50% to 99%, along with an α of 0.05 and a two-sided confidence interval width of 0.2p. To be statistically reliable, at least 402 respondents were needed.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire used in this survey comprised 5 parts: 1) sociodemographic characteristics and health status; 2) knowledge factors; 3) items on the HBM; 4) other items about COVID-19; and 5) acceptance of both the fourth dose and the heterogeneous booster dose of COVID-19 vaccines. All questions were constructed and evaluated by a panel of experts, including two public health experts and one epidemiologist specializing in infectious diseases, to ensure the validity.

Sociodemographic characteristics consisted of age, sex, location, economic region, education level, marital status, and occupation. For health status, two items were set to clarify the history of chronic diseases and vaccination history against COVID-19.

In terms of knowledge factors, we investigated respondents’ knowledge of COVID-19 on common symptoms, transmission routes, high-risk groups, characteristics of Omicron, infectivity of asymptomatic patients, and sequelae of COVID-19. The protective effect of COVID-19 vaccines against severe illness, death, and sequelae of COVID-19 and the change in vaccine effectiveness over time were also included. Each correct answer earned 1 point, out of a total of 20 points in this section. All participants were classified into “low (score 0–6),” “moderate (score 7–13)” and “high (score 14–20)” levels according to their final scores.

In the HBM section, we set 16 items in six dimensions, including perceived susceptibility (2 items), perceived severity (2 items), perceived impairment (3 items), perceived benefit (3 items), action cues (3 items) and self-efficacy (3 items). From low to high, each item scored from 1 to 3 points, which were assigned answers of “Disagree,” “Not clear,” and “Agree,” respectively. The reliability of this scale was confirmed by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α = 0.77).

To explore additional factors influencing the intention to receive the fourth dose and the heterogenous booster, we also asked respondents about the amount of daily time they spent on social media browsing COVID-19 and vaccine-related information, whether they had experienced a community lockdown within the past six months, and their satisfaction with the government’s response against COVID-19 and medical services during the pandemic.

COVID‑19 vaccine acceptance

We investigated two types of vaccination intentions. First, all participants were invited to answer the question “If a fourth dose of COVID-19 vaccine is available, would you be willing to receive it?” The response was “Yes” or “No or not sure.” Respondents who answered “No or not sure” were asked to specify the reasons for their vaccine hesitancy. People who selected “Yes” were then expected to further answer another question: “If available, would you prefer to receive a vaccine produced by a different technical route (heterologous booster) as the fourth dose?” The response was “Yes” or “No or not sure.” The heterologous booster in this study mainly refers to the recombinant adenovirus type 5 (AD5)-vectored COVID-19 vaccine Convidecia. The vaccine acceptance rate was defined as the proportion of people who answered “Yes” among all eligible respondents.

Statistical analysis

Means, standard deviations (SDs), frequencies and percentages were reported to summarize the characteristics of all participants. Comparisons among groups were performed using the t test and the χ2 test for continuous variables and categorical variables, respectively. We used multivariable logistic regression analyses to assess the association between vaccine acceptance and the investigated factors. To minimize the omission of influencing factors, all independent investigated variables were added to the model via a backward stepwise method (P < .1). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% CIs were calculated to express factors associated with vaccine acceptance. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used to assess the goodness of model fitting. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., NY, USA), and statistical significance was attributed to two-sided P values <.05.

Results

Basic characteristics of the study population

A total of 3,224 respondents were eventually included in our analyses. shows the basic characteristics of the study population. Among them, 90.1% were younger than 40 years old, 54.2% were male, 72.3% lived in urban areas, and 79.8% had at least a bachelor’s degree. Of note, 74.6% of the study participants indicated that they had experienced community lockdown within the past six months, and approximately 35% were dissatisfied or unsure with basic medical services during COVID-19. In this survey, 2,729 (84.6%) participants reported a vaccination history of a third dose, and most of them (93.4%) were satisfied with the government’s response to COVID-19.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population (n = 3,224).

Attitudes toward the fourth dose and heterologous booster

As shown in , 81.1% (95% CI: 79.8–82.5%) of 3,224 participants exhibited their intention to receive the fourth dose of COVID-19 vaccine if available, while the rate decreased to 72.6% (95% CI: 71.1–74.2%) for heterologous booster. People who had a higher education level, had a vaccination history, spent more time on social media, and learned more about COVID-19 and vaccines were prone to receive both the fourth dose and the heterologous booster (all Ptrend<0.05). The acceptability of both the fourth dose and heterologous booster differed significantly among the groups stratified by sex, marital status, satisfaction with the government’s response to COVID-19 and basic medical treatment during the epidemic. Younger adults only showed a relatively higher vaccine acceptance rate toward the fourth dose. Significant differences in heterologous booster acceptance were also found in the groups stratified by location and occupation.

Comparison of vaccine acceptance based on the HBM

shows the scores of all participants on the six main dimensions of the HBM and specific items for each dimension. According to our results, responders in the acceptant group scored higher on perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefit, cues to action, and self-efficacy than the hesitant group (all P < .001). In the dimension of perceived barriers, the hesitant group scored significantly higher than the acceptant group. Similar results were found in all specific items of each dimension, with only one exception in self-efficacy.

Table 2. Comparison of the acceptance of the fourth dose and heterologous booster based on HBM in China.

Factors related to the acceptance of the fourth dose of COVID-19 vaccine

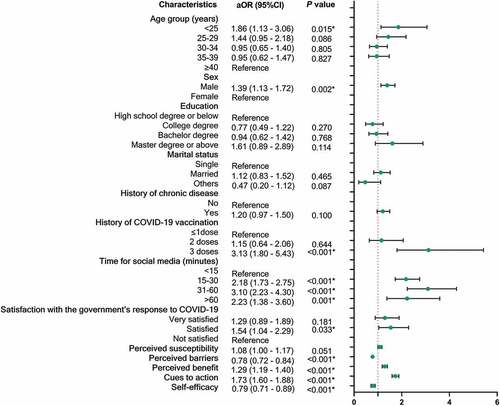

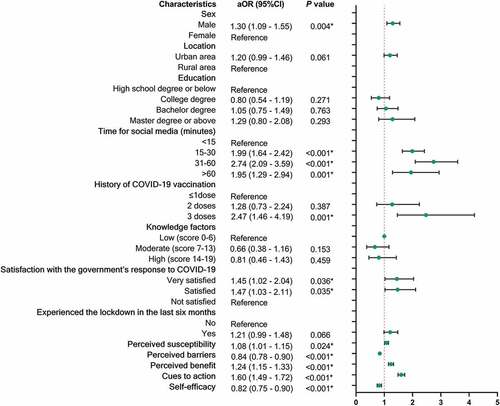

present the variables that were retained in the multivariable model after backward stepwise regression. Age, marital status, and history of chronic disease were included in but excluded in . Location, knowledge factors and lockdown experience in the last six months appear only in .

Figure 1. Multivariable logistic regression of the factors associated with the acceptance of the fourth dose of COVID-19 vaccine in China (n = 3,224).

Figure 2. Multivariable logistic regression of the factors associated with the acceptance of heterologous booster against COVID-19 in China (n = 3,224).

As shown in , males and adults younger than 25 years old showed a higher willingness to receive the fourth dose against COVID-19. People with a history of COVID-19 vaccination, especially for the third dose (aOR = 3.13, 95% CI: 1.80–5.43), and who spent more time on social media acquiring COVID-19 information (15–30 min: aOR = 2.18, 95% CI: 1.73–2.75; 31–60 min: aOR = 3.10, 95% CI: 2.23–4.30; >60 min: aOR = 2.23, 95% CI: 1.38–3.60) were more likely to accept the fourth dose than other groups. Most of the constructs in the HBM were significantly associated with the willingness to receive the fourth dose. Perceived benefit (aOR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.159–1.40) and cues to action (aOR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.60–1.88) were positively associated with the vaccine acceptance, while perceived barriers (aOR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.72–0.84) was a negative factor for vaccination willingness. Surprisingly, our results show that people with higher self-efficacy were less likely to get vaccinated (aOR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.71–0.89). Satisfaction with the government’s response to COVID-19 was also one of the positive factors affecting vaccination intention. However, the association between perceived susceptibility and vaccination intention was not significant for the fourth dose but was significant for the heterologous booster dose ().

Adjusted associations between the vaccine acceptance of the heterologous booster and potential influencing factors are exhibited in . Perceived susceptibility (aOR = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.01–1.05), perceived benefit (aOR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.15–1.33), and cues to action (aOR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.49–1.72) positively associated with the vaccine acceptance. However, with the scores on perceived barriers (aOR = 0.84, 95% CI: 0.78–0.90) and self-efficacy (aOR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.75–0.90) increasing, people’s willingness to vaccinate decreased. Sex, time for social media, history of COVID-19 vaccination, and satisfaction with the government were also significantly associated with vaccine acceptance of heterologous booster dose.

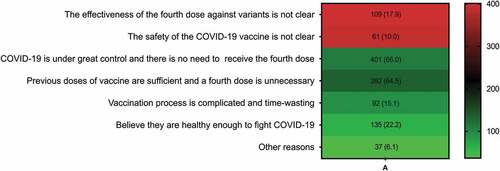

Reasons for vaccine hesitancy about the fourth dose

According to the results, 608 of 3,324 respondents (18.9%) were hesitant to receive the fourth dose of COVID-19 vaccine. shows all the reasons explaining vaccine hesitancy. Obviously, 66.0% of them believed that COVID-19 is under great control in China, and 64.5% of them considered that the previous doses already had sufficient protection against the variants. In addition, 17.9% expressed doubts about the extra protection provided by the fourth dose against variants, such as Omicron. The perceived time-consuming nature of vaccination and concerns about the safety of four consecutive doses also contributed to the vaccine hesitancy.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first national study to explore the willingness to receive the fourth dose and a heterologous booster against COVID-19 and its influencing factors. We found that among 3,224 respondents from 31 provinces, 81.1% exhibited their intention to receive the fourth dose, while the acceptability for a heterologous booster was 72.6%. Confidence in the current domestic situation and protection provided by previous vaccinations were the main reasons for vaccine hesitancy. Sex, COVID-19 vaccine history, time for social media, satisfaction with the government, and four dimensions of the HBM (perceived barriers, perceived benefit, cues to action, and self-efficacy) were all significantly associated with vaccine acceptability for both the fourth dose and the heterologous booster. However, the willingness to use heterologous booster was not associated with age but was associated with perceived susceptibility. Our results may provide a preliminary theoretical basis and practical support for the relevant institutions to clarify the vaccination intentions and influencing factors in advance, helping to carry out publicity and education for the target population and to promote vaccination coverage when necessary.

This study was carried out when several countries have started the fourth vaccination, while the domestic second booster dose had barely been widely rolled out. Our results show that 81.1% of the respondents were willing to receive the fourth dose against COVID-19 if necessary. There are limited studies on the willingness to receive the fourth dose now. Only one online study conducted by Galanis et al. found that the acceptance rate toward the fourth dose was 69.1% among a nurse group in Greece.Citation8 Globally, the acceptance rate of the third dose ranged from 41% to 98% in previous studies.Citation22,Citation32–34 A cross-sectional study conducted before the introduction of the third dose in the United States showed that only 61.8% of 2,138 respondents intended to receive it.Citation33 Another meta-analysis involving 31 publications systematically summarized vaccination acceptance rates in 33 countries, ranging from 23.6% to 97.0% at the beginning of initial vaccination.Citation35 Ecuador (97.0%), Malaysia (94.3%), Indonesia (93.3%) and China (91.3%) had the highest acceptance rates.Citation35 We found that when vaccines with different technical routes were selected as the fourth injection (heterologous booster), the vaccine acceptance rate decreased to 72.6%. This may be related to the lack of understanding of the safety and efficacy of heterologous vaccination, insufficient publicity efforts, and the late implementation of heterologous booster in China. Vaccine acceptance is a decisive factor for the successful control of a pandemic.Citation36,Citation37 Assessing people’s attitudes toward the fourth dose in advance, including heterologous booster, may help authorities quickly develop targeted coverage promotion measures when subsequent vaccinations are needed one day in the future.

Of the six main dimensions of the health belief model, perceived barriers were negatively associated with both vaccination intentions, while perceived benefits and action cues were positively associated. The perception of susceptibility may only influence people’s willingness to receive a heterogenous booster dose. Our results are consistent with previous studies, including studies related to vaccine acceptance of initial vaccinations and the first booster shots.Citation22,Citation28,Citation38–41 The association between perceived severity and vaccination intention was inconsistent.Citation42,Citation43 In addition, self-efficacy refers to a person’s ability to engage in a certain behavior and achieve the expected result in a specific situation.Citation44 The results from both of our regression models indicated that acceptance of the fourth dose and the heterologous booster decreased with the increasing self-efficacy scores. The results of previous studies mostly support a positive correlation between self-efficacy and preventive behavior, but our findings are inconsistent with this.Citation25,Citation45,Citation46 However, the results in show higher self-efficacy scores in the acceptant group. The above hints may suggest there were confounders that led to these inconsistent findings, and more reliable studies are expected to be performed. When changes in the external environment make it clear that it is time for people to receive a second booster shot, such as a more severe domestic COVID-19 epidemic, a decrease in the level of antibodies obtained from previous vaccination, and increased immune evasion of the novel variants, vaccine acceptance may increase rapidly due to a series of measures tailored to the health beliefs model.

Studies have demonstrated that heterologous booster immunization showed higher GMTs of neutralizing antibodies against different SARS-CoV-2 variants and better efficacy.Citation17,Citation18,Citation47 According to our results, people living in urban areas and employed by enterprises or public institutions reported a higher heterologous booster acceptance rate than other groups. This may be attributed to their higher level of education, greater access to information, greater acceptance of new things and higher pursuit of health, among others.Citation48–50 Trust is an intrinsic and potentially modifiable component of successful vaccination against COVID-19. Our study found that satisfaction with the government’s response to COVID-19 and the provision of basic health services also influenced vaccination intentions. Consistent with previous studies in 20 countries, trust in government was strongly and positively associated with COVID-19 acceptance and helped the public comply with recommended actions.Citation51,Citation52 Clear and consistent communication by government officials is critical to building public confidence in vaccine programs.Citation51,Citation52 In addition, people’s willingness to vaccinate increased as they spent more time browsing information about COVID-19 via social media. Wang et al. showed an association between social media and vaccine hesitancy.Citation53 Research on social media interventions and vaccine acceptance is an emerging field, so it is a good time to identify novel and innovative strategies that can increase vaccine acceptance on a large scale.Citation54,Citation55 Taking appropriate social media, strengthening community dissemination of COVID-19 and vaccine-related knowledge, and regulating medical professionals’ social media content are also effective measures to increase the vaccination rate.Citation53–56

Our results indicate that satisfaction with the situation of epidemic control and confidence in previous doses of vaccines were the two reasons owned more than half of the supportive explanations for vaccine hesitation. This survey was conducted before a new epidemic occurred in China, so favorable conditions may have made people hesitant to vaccinate. Obviously, people’s attitude toward vaccines will change with time and environment, which also suggests that the authorities should conduct publicity and education on the urgency of epidemic prevention and control and the necessity of a second booster dose when the fourth dose should be fully deployed or only targeted at certain vulnerable groups. In addition, uncertain additional protection against variants was also important. According to data from Israel’s Health Ministry, the number of severe cases among persons who were 60 years of age or older per 100,000 person-days was 1.5 and 177 in the aggregated four-dose groups compared with 3.9 and 361 in the three-dose group.Citation7 The results of a cohort study in Singapore by Celine Y. Tan et al. showed that among people aged 80 years or older, those who received the fourth dose had a lower risk of symptomatic infection, hospitalization, and severe illness than those who did not receive the fourth dose, with vaccine effectiveness rates of 22.2% (95% CI: 19.6–24.7%), 55.0% (95% CI: 51.8–58.3%), and 63.0% (95% CI: 56.3–68.5%), respectively.Citation57 Studies have provided sufficient evidence for additional protection provided by the fourth dose against symptomatic infection, severe illness, hospitalization, and death due to the omicron variant.Citation7–59

There are some limitations in our study. First, this online survey using an existing sample service database may lead to selection bias. Only users accessing the Internet have the chance of being selected. In this regard, we chose an online platform with a large sample base (approximately 6.2 million samples) and tried to increase the sample size under the condition of financial support. Stratified random sampling was also adopted to reduce selection bias. Second, the proportion of elderly people in the recruited population was very low. As a high-risk group for severe illness, death and sequelae after infection, the elderly population is the priority group for COVID-19 vaccination in all countries, and it is urgent to improve their effective immunization coverage. Our results need to be interpreted with caution due to the limitations of Internet accessibility for elderly individuals. We hope that follow-up studies can pay timely and targeted attention to the intention of the fourth dose among elderly individuals, immunocompromised people, and other groups with higher risk to provide more direct theoretical support and practical help for the subsequent possible vaccination plan.

Conclusions

81.1% of all participants were willing to receive the fourth dose, while the acceptability for a heterologous booster was 72.6%. Confidence in the current domestic situation and the effectiveness of previous vaccinations and uncertainty about extra protection were the main reasons for vaccine hesitancy. Sex, COVID-19 vaccine history, time for social media, satisfaction with the government, and four dimensions of the HBM (perceived barriers, perceived benefit, cues to action, and self-efficacy) were significantly associated with vaccine acceptability for both the fourth dose and the heterologous booster. It is of profound theoretical and practical significance to clarify the population’s willingness to vaccinate in advance and explore the relevant influencing factors for the subsequent development and promotion of fourth-dose vaccination strategies.

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | = | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| HBM | = | Health belief model |

| CI | = | Confidence intervals |

| aOR | = | Adjusted odds ratio. |

Author contributions

Conceptualization, C.Q., and J.L.; methodology and analysis, C.Q.; visualization, C.Q., and W.Y.; writing-original draft preparation, C.Q.; review and editing, L.T., M.D., Y.W., and Q.L.; supervision, M.L. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data in the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study met the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052–21126). Respondents were informed that their participation was voluntary, and consent was implied on the completion of the questionnaire.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants who enrolled in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- (JHU) CfSSaECaJHU. COVID-19 dashboard 2023. Updated 2023 Feb 5. [accessed 2023 Feb 5]. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- Rana R, Kant R, Huirem RS, Bohra D, Ganguly NK. Omicron variant: current insights and future directions. Microbiol Res. 2022;265:127204. [accessed 2022 Sept 25]. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2022.127204.

- Orgnization WH. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants 2022. Updated 2022 Nov 23. [accessed 2022 Nov 23]. https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/.

- Sun Y, Dai H, Wang P, Zhang X, Cui D, Huang Y, Zhang J, Xiang T. Will people accept a third booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine? A cross-sectional study in China. Front Public Health. 2022;10:914950. [accessed 2022 July 30]. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.914950.

- Yu B, Chang J. The first Chinese oral anti-COVID-19 drug Azvudine launched. Innovation. 2022;3(6):100321. [accessed 2022 Sept 16]. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2022.100321.

- Joshi S, Parkar J, Ansari A, Vora A, Talwar D, Tiwaskar M, Patil S, Barkate H. Role of favipiravir in the treatment of COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:501–10. [accessed 2020 Nov 2]. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.069.

- Bar-On YM, Goldberg Y, Mandel M, Bodenheimer O, Amir O, Freedman L, Alroy-Preis S, Ash N, Huppert A, Milo R. Protection by a fourth dose of BNT162b2 against Omicron in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(18):1712–20. [accessed 2022 Apr 6]. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2201570.

- Galanis P, Vraka I, Katsiroumpa A, Siskou O, Konstantakopoulou O, Katsoulas T, Mariolis‐sapsakos T, Kaitelidou D. Predictors of second COVID-19 booster dose or new COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among nurses: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2022. [accessed 2022 Nov 9]. doi:10.1111/jocn.16576.

- Tanne JH. Covid-19: Pfizer asks US regulator to authorise fourth vaccine dose for over 65s. Bmj. 2022;376:o711. [accessed 2022 Mar 19]. doi:10.1136/bmj.o711.

- (IVAC) IVAC. COVID-19 Data 2022. Updated 2022 Nov 24. [accessed 2022 Nov24]. https://view-hub.org/covid-19/effectiveness-studies?targetboost=boost2&field_covid_studies_variant_tabl=23732&field_covid_studies_population=23423&field_covid_studies_vaccine_all=23615.

- Orgnization WH. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19- 26 October 2022. Updated 2022 Oct 26. [accessed 2022 Nov23]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19—26-october-2022.

- Grewal R, Kitchen SA, Nguyen L, Buchan SA, Wilson SE, Costa AP, Kwong JC. Effectiveness of a fourth dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine against the omicron variant among long term care residents in Ontario, Canada: test negative design study. Bmj. 2022;378:e071502. [accessed 2022 July 7]. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-071502.

- Magen O, Waxman JG, Makov-Assif M, Vered R, Dicker D, Hernán MA, Lipsitch M, Reis BY, Balicer RD, Dagan N. Fourth dose of BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide setting. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(17):1603–14. [accessed 2022 Apr 14]. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2201688.

- Rodewald L, Wu D, Yin Z, Feng Z. Vaccinate with confidence and finish Strong. China CDC Wkly. 2022;4(37):828–31. [accessed 2022 Oct 27]. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2022.172.

- Press conference of the state council joint prevention and control mechanism 2022. Updated 2022 Nov 5. [accessed 2022 Nov 23]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/gwylflkjz212/index.htm.

- Zhong J, Liu S, Cui T, Li J, Zhu F, Zhong N, Huang W, Zhao Z, Wang Z. Heterologous booster with inhaled adenovirus vector COVID-19 vaccine generated more neutralizing antibodies against different SARS-CoV-2 variants. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11(1):2689–97. [accessed 2022 Oct 6]. doi:10.1080/22221751.2022.2132881.

- Atmar RL, Lyke KE, Deming ME, Jackson LA, Branche AR, El Sahly HM, Rostad CA, Martin JM, Johnston C, Rupp RE, et al. Homologous and heterologous Covid-19 booster vaccinations. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(11):1046–57. [accessed 2022 Jan 27]. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2116414.

- Deng J, Ma Y, Liu Q, Du M, Liu M, Liu J. Comparison of the effectiveness and safety of heterologous booster doses with homologous booster doses for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10752. [accessed 2022 Sept 10]. doi:10.3390/ijerph191710752.

- Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175–83. [accessed 1988 Jan 1]. doi:10.1177/109019818801500203.

- Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1–47. [accessed 1984 Jan 1]. doi:10.1177/109019818401100101.

- Cummings KM, Jette AM, Rosenstock IM. Construct validation of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1978;6(4):394–405. [accessed 1978 Jan 1]. doi:10.1177/109019817800600406.

- Qin C, Wang R, Tao L, Liu M, Liu J. Acceptance of a third dose of COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors in China based on health belief model: a national cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2022;10(1). [accessed 2022 Jan 23]. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.986916.

- Hossain MB, Alam MZ, Islam MS, Sultan S, Faysal MM, Rima S, Hossain MA, Mamun AA. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the adult population in Bangladesh: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2021;16(12):e0260821. [accessed 2021 Dec 10]. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260821.

- Qin C, Wang R, Tao L, Liu M, Liu J. Association between risk perception and acceptance for a booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine to children among child caregivers in China. Front Public Health. 2022;10:834572. [accessed 2022 Apr 5]. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.834572.

- Chen H, Li X, Gao J, Liu X, Mao Y, Wang R, Zheng P, Xiao Q, Jia Y, Fu H, et al. Health belief model perspective on the control of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and the promotion of vaccination in China: web-based cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(9):e29329. [accessed 2021 July 20]. doi:10.2196/29329.

- Hossain MB, Alam MZ, Islam MS, Sultan S, Faysal MM, Rima S, Hossain MA, Mamun AA. Health belief model, theory of planned behavior, or psychological antecedents: what predicts COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy better among the Bangladeshi adults? Front Public Health. 2021;9:711066. [accessed 2021 Sept 8]. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.711066.

- Suess C, Maddock J, Dogru T, Mody M, Lee S. Using the health belief model to examine travelers’ willingness to vaccinate and support for vaccination requirements prior to travel. Tour Manag. 2022;88:104405. [accessed 2021 Aug 31]. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104405.

- Tao L, Wang R, Han N, Liu J, Yuan C, Deng L, Han C, Sun F, Liu M, Liu J. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women in China: a multi-center cross-sectional study based on health belief model. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(8):2378–88. [accessed 2021 May 15]. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1892432.

- Vermandere H, van Stam MA, Naanyu V, Michielsen K, Degomme O, Oort F. Uptake of the human papillomavirus vaccine in Kenya: testing the health belief model through pathway modeling on cohort data. Global Health. 2016;12(1):72. [accessed 2016 Nov 17]. doi:10.1186/s12992-016-0211-7.

- Zambri F, Perilli I, Quattrini A, Marchetti F, Colaceci S, Giusti A. Health belief Model efficacy in explaining and predicting intention or uptake pertussis vaccination during pregnancy. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2021;57(2):167–73. [accessed 2021 June 17]. doi:10.4415/ann_21_02_09.

- Bureau SS. Bulletin of the seventh national census 2021. [ Updated 2021 May 11. [accessed 2022 Nov24]. http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2021-05/13/content_5606149.htm.

- Abdelmoneim SA, Sallam M, Hafez DM, Elrewany E, Mousli HM, Hammad EM, Elkhadry SW, Adam MF, Ghobashy AA, Naguib M, et al. COVID-19 vaccine booster dose acceptance: systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7(10):298. [accessed 2022 Oct 27]. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed7100298.

- Yadete T, Batra K, Netski DM, Antonio S, Patros MJ, Bester JC. Assessing acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine booster dose among adult Americans: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021;9(12):1424. [accessed 2021 Dec 29]. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121424.

- Yoshida M, Kobashi Y, Kawamura T, Shimazu Y, Nishikawa Y, Omata F, Zhao T, Yamamoto C, Kaneko Y, Nakayama A, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine booster hesitancy: a retrospective cohort study, Fukushima vaccination community survey. Vaccines. 2022;10(4). [accessed 2022 Apr 24]. doi:10.3390/vaccines10040515.

- Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9(2). [accessed 2021 Mar 7]. doi:10.3390/vaccines9020160.

- Harrison EA, Wu JW. Vaccine confidence in the time of COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(4):325–30. [accessed 2020 Apr 23]. doi:10.1007/s10654-020-00634-3.

- Palamenghi L, Barello S, Boccia S, Graffigna G. Mistrust in biomedical research and vaccine hesitancy: the forefront challenge in the battle against COVID-19 in Italy. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):785–88. [accessed 2020 Aug 19]. doi:10.1007/s10654-020-00675-8.

- Wang R, Tao L, Han N, Liu J, Yuan C, Deng L, Han C, Sun F, Chi L, Liu M, et al. Acceptance of seasonal influenza vaccination and associated factors among pregnant women in the context of COVID-19 pandemic in China: a multi-center cross-sectional study based on health belief model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):745. [accessed 2021 Nov 5]. doi:10.1186/s12884-021-04224-3.

- Lin Y, Hu Z, Zhao Q, Alias H, Danaee M, Wong LP. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: a nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(12):e0008961. [accessed 2020 Dec 18]. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008961.

- Baccolini V, Renzi E, Isonne C, Migliara G, Massimi A, De Vito C, Marzuillo C, Villari P. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Italian university students: a cross-sectional survey during the first months of the vaccination campaign. Vaccines. 2021;9(11):1292. [accessed 2021 Nov 28]. doi:10.3390/vaccines9111292.

- Bartoš V, Bauer M, Cahlíková J, Chytilová J. Communicating doctors’ consensus persistently increases COVID-19 vaccinations. Nature. 2022;606(7914):542–49. [accessed 2022 June 2]. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04805-y.

- Du M, Tao L, Liu J. The association between risk perception and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for children among reproductive women in China: an online survey. Front Med. 2021;8:741298. [accessed 2021 Sept 28]. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.741298.

- Kelly BJ, Southwell BG, McCormack LA, Bann CM, MacDonald PDM, Frasier AM, Bevc CA, Brewer NT, Squiers LB. Predictors of willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):338. [accessed 2021 Apr 14]. doi:10.1186/s12879-021-06023-9.

- Orji R, Vassileva J, Mandryk R. Towards an effective health interventions design: an extension of the health belief model. Online J Public Health Inform. 2012;4(3). [accessed 2012 Jan 1]. doi:10.5210/ojphi.v4i3.4321.

- Shahnazi H, Ahmadi-Livani M, Pahlavanzadeh B, Rajabi A, Hamrah MS, Charkazi A. Assessing preventive health behaviors from COVID-19: a cross sectional study with health belief model in Golestan Province, Northern of Iran. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):157. [accessed 2020 Nov 19]. doi:10.1186/s40249-020-00776-2.

- Jadil Y, Ouzir M. Exploring the predictors of health-protective behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-country comparison. Environ Res. 2021;199:111376. [accessed 2021 May 28]. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.111376.

- Costa Clemens SA, Weckx L, Clemens R, Almeida Mendes AV, Ramos Souza A, Silveira MBV, da Guarda SNF, de Nobrega MM, de Moraes Pinto MI, Gonzalez IGS, et al. Heterologous versus homologous COVID-19 booster vaccination in previous recipients of two doses of CoronaVac COVID-19 vaccine in Brazil (RHH-001): a phase 4, non-inferiority, single blind, randomised study. Lancet. 2022;399(10324):521–29. [accessed 2022 Jan 26]. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(22)00094-0.

- Andrejko KL, Pry J, Myers JF, Jewell NP, Openshaw J, Watt J, Jain S, Lewnard JA, Samani H, Li SS, et al. Prevention of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by mRNA-Based vaccines within the general population of California. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(8):1382–89. [accessed 2021 July 21]. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab640.

- Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, Wiblishauser MJ, Sharma M, Webb FJ. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):270–77. [accessed 2021 Jan 4]. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x.

- Quinn SC, Jamison AM, Freimuth V. Communicating effectively about emergency use authorization and vaccines in the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(3):355–58. [accessed 2020 Nov 26]. doi:10.2105/ajph.2020.306036.

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225–28. [accessed 2020 Oct 22]. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9.

- Faasse K, Newby J. Public perceptions of COVID-19 in Australia: perceived risk, knowledge, health-protective behaviors, and vaccine intentions. Front Psychol. 2020;11:551004. [accessed 2020 Oct 30]. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.551004.

- Wang R, Qin C, Du M, Liu Q, Tao L, Liu J. The association between social media use and hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccine booster shots in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(5):2065167. [accessed 2022 June 8]. doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2065167.

- Limaye RJ, Holroyd TA, Blunt M, Jamison AF, Sauer M, Weeks R, Wahl B, Christenson K, Smith C, Minchin J, et al. Social media strategies to affect vaccine acceptance: a systematic literature review. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021;20(8):959–73. [accessed 2021 July 2]. doi:10.1080/14760584.2021.1949292.

- Daley MF, Glanz JM. Using social media to increase vaccine acceptance. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(4, Supplement):S32–33. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2020.10.018.

- Qin C, Liu Q, Du M, Yan W, Tao L, Wang Y, Liu M, Liu J. Neighborhood social cohesion is associated with the willingness toward the booster dose of COVID-19 vaccines among the Chinese older population. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(6):2140530. [accessed 2022 Nov 15]. doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2140530.

- Tan CY, Chiew CJ, Lee VJ, Ong B, Lye DC, Tan KB. Effectiveness of a fourth Dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine against Omicron variant among elderly people in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(11):1622–23. [accessed 2022 Sept 13]. doi:10.7326/m22-2042.

- Gazit S, Saciuk Y, Perez G, Peretz A, Pitzer VE, Patalon T. Short term, relative effectiveness of four doses versus three doses of BNT162b2 vaccine in people aged 60 years and older in Israel: retrospective, test negative, case-control study. Bmj. 2022;377:e071113. [accessed 2022 May 25]. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-071113.

- Mallapaty S. Fourth dose of COVID vaccine offers only slight boost against Omicron infection. Nature. 2022. [accessed 2022 Feb 25]. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-00486-9.