ABSTRACT

Prior to the COVID pandemic, Puerto Rico (PR) had one of the highest Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine rates in the United States. The COVID pandemic and administration of COVID vaccines might have impacted attitudes toward HPV vaccination. This study compared attitudes toward HPV and COVID vaccines with respect to school-entry policies among adults living in PR. A convenience sample of 222 adults (≥21 years old) completed an online survey from November 2021 to January 2022. Participants answered questions about HPV and COVID vaccines, attitudes toward vaccination policies for school-entry, and perceptions of sources of information. We assessed the magnitude of association between the agreement of school-entry policies for COVID and HPV vaccination by estimating the prevalence ratio (PRadjusted) with 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI). The most trusted source of information for HPV and COVID vaccines were healthcare providers (42% and 17%, respectively) and the CDC (35% and 55%, respectively), while the least trusted were social media (40% and 39%, respectively), and friends and family (23% n = 47, and 17% n = 33, respectively). Most participants agreed that HPV (76% n = 156) and COVID vaccines (69% n = 136) should be a school-entry requirement. Agreement with school policy requiring COVID vaccination was significantly associated with agreement of school policy requiring HPV vaccination (PRadjusted:1.96; 95% CI:1.48–2.61) after controlling for potential confounders. Adults living in PR have an overall positive attitude about mandatory HPV and COVID vaccination school-entry policies, which are interrelated. Further research should elucidate the implications of the COVID pandemic on HPV vaccine attitudes and adherence rates.

Introduction

The Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States of America (USA).Citation1 In 2018, about 13 million new HPV infections were estimated in the USA.Citation1 Almost 80% of HPV-associated cancers are attributed to HPV infection; of those, 92% could be prevented with HPV immunization.Citation2 The HPV vaccine (9vHPV) currently used in the USA targets the HPV-associated cancer variants.Citation3 Given that the HPV vaccine is more effective before any exposure to HPV, in 2019 the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended HPV vaccination at age 11 or 12, catch-up vaccinations for all persons through age 26, and selective vaccination in individuals between 27 and 45 years old.Citation4

The burden of HPV-malignancies is a public health concern in the USA mainland and its territories. Puerto Rico (PR) has the highest incidence of cervical and penile cancers in all states and territories.Citation5 To address these health disparities, on January 2010, Law No. 9 was enacted in PR to provide the HPV vaccine to girls aged 11 to 18 at no out-of-pocket cost. This law was later expanded in 2012 to include boys.Citation6 Most recently, on August 2018, the PR Secretary of Health added the HPV vaccine to the list of required vaccines for school entrance among children aged 11 and 12 years.Citation7 In the 2019–2020 academic period, the school HPV vaccine requirement was expanded to children between 11 to 14 years old and later broadened its reach in 2020–2021 to students up to 16 years of age. Prior to and during the implementation period, the PR Department of Health, the academia, health care professionals, and community coalitions were actively promoting the HPV vaccine.Citation6 However, concerns about vaccine safety, violation of patient autonomy, and lack of education about HPV and vaccines were documented by the PR media before implementing the HPV school-entry requirement.Citation8 Despite the reluctance to the HPV vaccine by some community groups, recent analyses by this team from the PR Immunization Registry comparing the period between 2017 (a pre-policy year) to 2019 (post-policy), identified 54% increase in initial HPV vaccination among children aged 11 and 12 (58.3% in 2017 to 89.8% in 2019).Citation7,Citation9 This suggests that mandatory school requirement for the HPV vaccine is an effective strategy to increase HPV vaccine uptake among this group.

Unfortunately, this effort was later interrupted by environmental disasters in PR (hurricanes and earthquakes)Citation10 added to the COVID pandemic.Citation11 To control the pandemic, the government of PR was actively enforcing strict restrictions to control COVID infections and promoted COVID vaccination. Between the period of 2020 to 2022, a total of 68 executive orders were made by the Puerto Rican government related to COVID control, of those, ten specifically targeted COVID vaccines and booster requirements.Citation12 For example, in 2021, the government required vaccination completion among governmental employees,Citation13 contractors, and healthcare and lodging (e.g., hotel) workers.Citation14 The government also required all students, starting at age 5, to be fully vaccinated against COVID to have in-person classes.Citation15 In January 2022, a mandate requiring a booster shot was also enacted for students (to continue in-person learning) and for access and visit to cinemas, theaters, and massive cultural activities,Citation16 and in March 2022, the COVID vaccinations mandates were lifted. The PR mandates led to a completion rate of 87% for the primary COVID vaccination series among the eligible population in 2022, one of the highest in the US.Citation17,Citation18 Nevertheless, while the COVID vaccination was promoted during the pandemic the HPV vaccination rates significantly decreased in the US and worldwide,Citation19–21 and this could be attributed to reduced vaccination access.Citation22,Citation23

Furthermore, concerns about COVID vaccine safety and efficacy, its novelty, the rigor of testing, and lack of trust in the government have been documented in PR.Citation24 The easy access to health information via the Internet (i.e., social media) can influence vaccination decisions and hesitancy.Citation25,Citation26 The rate at which false health information can now be propagated through social and traditional media across the globe is alarming.Citation27 Considering that it has been documented that health professionals, academic institutions, and government agencies tend to be the most trusted sources of COVID information,Citation28 an active role of these groups on social media facilitating reliable health information is needed.Citation25,Citation26

Due to the detrimental effect of widespread misleading information about COVID vaccines that could have influenced individuals’ overall perceptions about vaccines,Citation29 including HPV vaccines, it is important to evaluate how individuals’ attitudes about these vaccines are related. To provide some light on this relationship, this study aims to access and compare the attitudes of individuals to school policies that require the HPV and COVID vaccination, as well as knowledge and perceptions of trusted and untrusted sources of information about these vaccines. We also evaluated how participants’ perceptions about trusted and untrusted sources of information are related to attitudes about school vaccination policies and to perceived knowledge of HPV and COVID vaccines.

Methods

Participants and procedures

This cross-sectional study is part of a study entitled Implementation of School-Entry Policies for Human Papillomavirus Vaccination (HPV-PIVac Study R01CA232743). The HPV-PIVac Study is an ongoing study assessing the impact of compulsory HPV vaccination for school entry in PR. For the current study, we recruited Spanish-speaking participants ≥21 years old living in PR through a HPV-PIVac study Facebook advertisement campaign. We defined the target population using Facebook Ads Manager tool, and some organizations also shared the campaign on their Facebook pages.

The study survey assessed participants’ opinions about HPV and the COVID vaccines. A panel of experts reviewed and approved a final version of the survey. Between November 19, 2021 to January 13, 2022, a total of 242 individuals consented and opened the online survey, 20 participants were excluded for the following reasons: did not answer any question (n = 12), were younger than 21 (n = 6), did not reported age (n = 1), and answered <10% of the questionnaire (n = 1). The online survey was in Spanish and available through the Qualtrics platform. Participants’ contact information was collected for those interested in a $25 lottery and/or a follow-up phone interview. The University of Puerto Rico Medical Science Campus Institutional Review Board approved this study (Protocol number: A8060218).

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

Self-reported data about age, sex, marital status, highest education level achieved, current employment situation, parent or guardian status, the total number of children younger than 18 and between ages 11 and 16, household income and health care coverage were collected. Some sociodemographic questions (i.e., age, partner status, highest education level achieved, and household income) were obtained from the Spanish version of the Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccine Survey.Citation30 Participants also reported their COVID vaccine status (completed doses, partial doses, or have not received the vaccine).

HPV and COVID vaccines knowledge

In terms of perceived knowledge, participants were asked “How much would you say you know about the human papillomavirus vaccine?” and “How much would you say you know about the COVID vaccine?.” Possible answers were (0) No knowledge/(1) Little knowledge/(2) Moderate knowledge/(3) A lot of knowledge.

Attitudes toward vaccination policies

Participants were asked about their attitudes about HPV vaccines as a policy for school entry by asking: “Do you agree with the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine being included in the list of required vaccines for people between 11 and 16 years old to go to school in Puerto Rico?” In relation to COVID vaccines, participants were also asked “Currently, would you agree that the COVID vaccine is included in the list of vaccines required for children and youth to attend school in Puerto Rico?” Possible answers were (0) No/(1) Yes/(99) I don’t know.

Sources of information for HPV and COVID vaccines

Participants’ perception of trusted and untrusted sources of information questions were adapted from Axios/Ipsos Coronavirus Index (Wave 33).Citation31 Regarding HPV vaccine sources, participants were asked, “Which of the following resources are you most confident in providing accurate information about the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine?” and “Which of the following resources are you least confident in providing accurate information about the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine?” In terms of sources of information for the COVID vaccine, participants were asked, “Which of the following resources are you most confident in providing accurate information about the COVID vaccine?” and “Which of the following resources are you least confident in providing accurate information about the COVID vaccine?” For all questions, participants selected one option between the following alternatives: Department of Health/Physician or health provider/Department of Education/School or Colleges (K-12)/Coalitions or community groups/Social Media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram)/Internet/Friends and family/CDC, Centers for Control and Disease Prevention.

Statistical analysis

To describe the study group, we initially presented the overall distribution of the following variables: sociodemographic data, HPV and COVID vaccine knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of trusted and untrusted sources of information. The variable age was summarized with measures of central tendency and dispersion (mean ± SD, median, range). Categorical variables were summarized with absolute numbers and percentages. To evaluate differences between HPV and COVID vaccine perceived knowledge and school policies attitudes, we calculated paired t-test and X2 test, respectively. We also assessed group differences by parental status (participants with children vs without children) by calculating independent t-test and X2 tests for these variables of interest. For these statistical analyses, HPV and COVID vaccine attitudes were dichotomized and coded as follows: Yes = 1 and No/Do not know = 0. We assessed the magnitude of the association between agreement with HPV and COVID vaccination school policies by estimating the prevalence ratio (PRadjusted) with 95% confidence intervals using the log-binomial model.Citation32 We performed this estimation with and without potential demographic confounders (age, sex, education, and having children between the ages of 11 and 16). Previously, we assessed the interaction terms between predictors of this model using the likelihood ratio test. However, we did not find any significant interaction terms (p > .05). We additionally conducted log-binomial models with a subsample (only including the participants with children) to assess the relationship of this association among this group. However, in this analysis, the model was not adjusted by sex, given that 89% of this subsample were women. Data management and statistical analysis were performed using SPSS (version 27, IBM) and Stata version 14 (USA: StataCorp LLC).

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 222 participants from PR completed the questionnaire. Demographic characteristics are shown in . Participants’ average age was 37 years old (median = 34; range: 21–70; SD = 11), the majority were female (87%; n = 194), with at least some college of education (92%; n = 205). About half of the sample had private medical insurance (58%; n = 129), children (58%; n = 129), and annual household income less than $25,000 (51%; n = 114). Most participants (80%; n = 178) completed the COVID vaccine doses.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants in this study (n = 222).

Knowledge and attitudes

Participants perceived knowledge about the HPV vaccine was moderate (mean = 1.92; SD = .85; range = 0–3), while for the COVID vaccine, it was moderately high (mean = 2.50; SD = .57; range = 1–3), and this difference was statistically significant (t-test = −10.03; p < .001). Participants perceived knowledge about the HPV and COVID vaccines were significantly correlated (r = .428; p < .001). More than half of the participants agreed that HPV (76%; n = 156) and COVID vaccines (69%; n = 136) should be required for school entry, and this difference was significant (X2 = 40.88; p < .001; see ). No significant differences were found for HPV vaccine knowledge (participants with children: mean = 1.93, SD = .87; participants without children: mean = 1.90; SD = .84; t-test = 0.26; p = .80) and COVID vaccine knowledge by children status (participants with children: mean = 2.46, SD = .60; participants without children: mean = 2.56; SD = .52; t-test = −1.22; p = .23). No significant difference was found for the association between agreement that HPV vaccine school-entry policy by children status (participants with children: 72% agreed, n = 84; participants without children: 80% agreed, n = 72; X2 = 1.59; p = .21); however, participants with children were less likely to agree that COVID vaccines should be required for school-entry (participants with children: 57% agreed, n = 64; participants without children: 86% agreed, n = 72; X2 = 18.45; p < .001).

Table 2. HPV and COVID vaccines knowledge and attitudes for school-entry policy.

Trusted and untrusted source of information

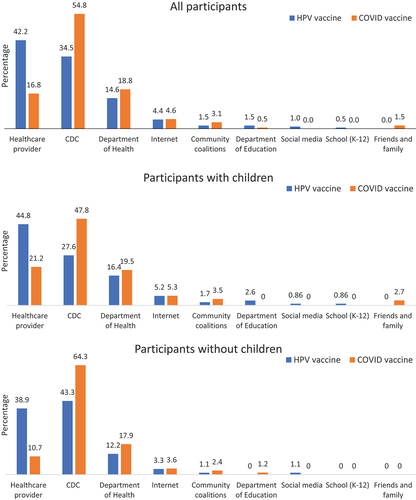

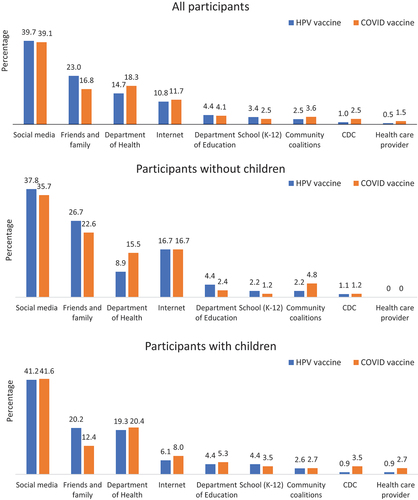

Participants most frequently endorsed trusted sources of information for HPV and COVID vaccines were: health care providers, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Department of Health (see ). Particularly, for the HPV vaccine, healthcare providers (42%; n = 87) and the CDC (35%; n = 71) were the two most trusted sources of information, while for the COVID vaccine, the CDC (55%, n = 108) and the Department of Health (19%; n = 37) were the most trusted sources. The two most trusted sources of information for HPV and COVID vaccines among participants with children were healthcare providers (45%; n = 54, and 21%; n = 24, respectively) and the CDC (28%; n = 32, and 48%; n = 54, respectively). The least trusted sources of information for HPV and COVID vaccines were social media (40%; n = 81, and 39%; n = 77, respectively), family and friends (23%; n = 47, and 17%; n = 33, respectively), and the Department of Health (15%; n = 30 and 18%; n = 36, respectively; see ). Similar findings were found for participants with children (see ).

HPV and COVID vaccines association

Agreement with the school-entry policy requiring COVID vaccination was positively associated with agreement with the school-entry policy requiring HPV vaccination (PRadjusted:1.96; 95% CI:1.48–2.61) after adjusting for age, sex, education, and having children between the age of 11 and 16 years (see ). Additional models with only parents with children show as well a significant association between agreement with the school-entry policy requiring COVID and agreement with a school-entry policy requiring HPV vaccination (PRadjusted:2.01; 95% CI:1.45–2.78) (data not shown).

Table 3. Magnitude of the association between the agreement for the HPV and COVID vaccines requirements for school-entry.

Discussion

Mass COVID vaccination uptake is recommended to control the COVID pandemic, and significant efforts have been made to promote COVID vaccines. In our study, we found -as expected- that most participants knew about COVID vaccines. Also, participants reported a higher level of COVID vaccine knowledge than for the HPV vaccine, even though, HPV vaccines have been accessible since 2006 in the USA and PR,Citation6 and HPV vaccination has been a school entry requirement in PR since 2018. Thus, the impact of the COVID pandemic has led to higher public perceived knowledge and promotion of the COVID vaccine, in contrast to HPV vaccines, for which education efforts have targeted a specific age group (9 to 26 years old)—the individuals who benefit the most from the vaccine.Citation33

Considering that HPV vaccines are also recommended to young adults up to 26 years old,Citation34 post hoc analysis indicated that among the participants between the ages 21 to 26 in our sample, only 67% reported moderate to strong HPV vaccine knowledge. This suggests that greater efforts are needed to improve HPV vaccine knowledge among the general population, especially young adults. Nevertheless, when we evaluated participants’ agreement with HPV vaccine school-entry mandatory policies, most participants reported agreeing with it. This is encouraging as agreement with vaccine mandate is associated with greater vaccine intention.Citation35

Supported by previous studies evaluating COVID vaccine trust and acceptance,Citation36,Citation37 we found that trust in the government and the Department of Health was associated with COVID vaccine acceptance. When evaluating trusted sources of information, we found that the Department of Health was considered by 14–19% of participants as the most trusted source of information for HPV and COVID vaccines, and similarly, about 14–18% rated the Department of Health as the least trusted source of information. It is concerning and contradictory to what we expected that a proportion of individuals consider the Department of Health the least trusted source of information regarding its role in implementing HPV and COVID vaccine policies in PR. Considering that recent findings indicate that mandatory vaccination policies could lead to greater discontent and more vaccine reactance in individuals with negative attitudes about mandates,Citation35 this disagreement in trust could be attributed in part to the PR governor’s administrative orders in support of the Department of Health, dictating COVID vaccine requirements to gain access to specific work and social settings.Citation12–16,Citation38 Specifically, political conservatives tend to have greater distrust in the government and lower COVID vaccine trust.Citation37 In PR, the administrative orders were controversial and created resistance from those against vaccination, anti-vax and conservative groups to speak out against the compulsory requirements,Citation39–41 and provoking legal actions.Citation42 Nevertheless, recent studies also found that when individuals are informed about the vaccine’s public health and economic benefits, it reduces vaccine reactance.Citation35 In PR, the COVID vaccines have been arduously promoted by community-based organizations, health providers, and religious-based entities.Citation43–47 While the mandatory efforts might have led to greater reactance among specific groups in PR, it also had the expected impact of increasing COVID uptake among the general population. These mandatory policies, in combination with public health education, resulted in PR being the US jurisdiction with the highest percentage (86.7%) of the total population with completed primary COVID vaccine series.Citation18 Nevertheless, the mandatory policies in PR might have resulted in vaccine distrust among specific population sub-groups, and efforts should be made to repair the trust of vaccines and the Department of Health.

Attitudes about one vaccine could influence individual attitudes toward other vaccines. Prior studies have found that individuals with a history of receiving the influenza vaccine were more willing to take the COVID vaccine.Citation48,Citation49 Similarly, a study in PR found that in relation to vaccine-hesitant parents, a greater proportion of parents who are not hesitant to vaccines reported intention of vaccinating their children for COVID. Citation50 A recent review of factors affecting vaccine attitudes influenced by the pandemic, suggested that the pandemic increased vaccination hesitancy.Citation29 For example, a study in California, USA evaluating parents’ perspectives on routine vaccinations found that childhood vaccine confidence remained the same during the pandemic, but vaccine hesitancy and risk perception increased.Citation51,Citation52 Similarly, a study in Saudi Arabia suggested a possible increase in caregivers’ routine vaccination hesitancy during the pandemic.Citation53,Citation54 A longitudinal study among older adults in the United Kingdom found that while older adults reported less complacency (e.g., vaccination is low in priority) and mistrust of vaccine benefits, they reported greater calculation and worry about vaccines later in the pandemic.Citation55 Although prior studies have not evaluated the pandemic implications on HPV vaccine attitudes and uptake, a previous systematic review identified that children’s and parents’ positive vaccine attitudes, previous vaccination history, and higher vaccine-related knowledge are related to HPV vaccine uptake.Citation56 As expected, this study found that individuals with positive attitudes about COVID vaccine school policies also had positive attitudes about HPV vaccine school policies. This finding suggests that COVID vaccine perception is related to HPV vaccine attitudes and vice versa.

Although this study provides relevant information about the attitudes toward HPV and COVID vaccines among adults living in PR, limitations must be considered. First, due to convenience sampling, findings might reflect selection bias, where participants with more positive attitudes about HPV and COVID vaccines might be more interested in participating in this study. Second, due to the source of participant recruitment – Facebook–and sample characteristics (i.e., highly educated sample with low socioeconomic status), findings might not be generalizable to the general population. Third, only 20% of the participants had children between the ages of 11 to 16, among whom we expected to have greater knowledge of HPV vaccines. Finally, participants’ perceived knowledge about HPV and COVID vaccines was measured by perceived self-report, not objectively. Additional research is needed to evaluate participants’ knowledge about HPV and COVID vaccines objectively.

Despite the previous limitations, this study elucidated perceived knowledge, attitudes about school-entry policies, and trusted sources of information of the HPV and COVID vaccines among adults living in PR. Findings suggest a relationship exists between the attitudes toward the HPV and COVID vaccines and raise opportunities to assess the individuals’ perceptions of the Department of Health of PR. Further research is needed to identify the impact of the positive and negative messages about the COVID vaccines on the attitudes toward the HPV vaccine in the general public. In addition, future studies should assess the perception of the Department of Health immunization policies over time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections prevalence, incidence, and cost estimates in the United States. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/prevalence-2020-at-a-glance.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancers associated with human papillomavirus, United States—2014–2018. USCS Data Brief. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention UDoHaHS; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/pdf/USCS-DataBrief-No26-December2021-h.pdf.

- Petrosky E, Bocchini JA Jr, Hariri S, Chesson H, Curtis CR, Saraiya M, Unger ER, Markowitz LE. Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1.

- Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, Unger ER, Romero JR, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. Wiley Online Lib. 2019;19(11):3202–9. doi:10.1111/ajt.15633.

- Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, Markowitz LE, Thomas CC, Thompson TD, Razzaghi H, Saraiya M. Human papillomavirus–associated cancers—United States, 2008–2012. Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2016;65(26):661–6. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6526a1.

- Medina-Laabes DT, Colón-López V, Rivera-Figueroa V, Vázquez-Otero C, Arroyo-Morales GO, Arce-Cintrón L, Fernández-Rivera P, Vega I, Soto-Abreu R, Díaz-Miranda OL, et al. Esfuerzos realizados en Puerto Rico hacia la consolidación de políticas públicas para la prevención de cánceres asociados al VPH. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 2022;46:1. doi:10.26633/RPSP.2022.3.

- Colón-López V, Vázquez-Otero C, Rivera-Figueroa V, Arroyo-Morales GO, Medina-Laabes DT, Soto-Abreu R, Díaz-Miranda OL, Rivera Á, Cardona I, Ortiz AP, et al. HPV vaccine school entry requirement in Puerto Rico: historical context, challenges, and opportunities. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:18. doi:10.5888/pcd18.210035.

- Colón-López V, Rivera-Figueroa V, Arroyo-Morales GO, Medina-Laabes DT, Soto-Abreu R, Rivera-Encarnación M, Díaz-Miranda OL, Ortiz AP, Wells KB, Vázquez-Otero C, et al. Content analysis of digital media coverage of the human papillomavirus vaccine school-entry requirement policy in Puerto Rico. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11311-9.

- Colon-Lopez V, Hull P, Diaz-Miranda O, Machin M, Vega-Jimenez I, Medina-Laabes DT, Soto-Abreu R, Fernandez M, Ortiz AP, Suárez-Pérez EL, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine initiation and up-to-data vaccine coverage for adolescents after the implementation of school-entry policy in Puerto Rico. PLOS Global Public Health. 2022;2(11):e0000782. doi:10.1371/journal.pgph.0000782.

- Colón-López V, Díaz-Miranda OL, Medina-Laabes DT, Soto-Abreu R, Vega-Jimenez I, Ortiz AP, Suárez EL. Effect of Hurricane Maria on HPV, Tdap, and meningococcal conjugate vaccination rates in Puerto Rico, 2015–2019. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2021 Dec 2;17(12):5623–7. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2004809.

- Gilkey MB, Bednarczyk RA, Gerend MA, Kornides ML, Perkins RB, Saslow D, Sienko J, Zimet GD, Brewer NT. Getting human papillomavirus vaccination back on track: protecting our national investment in human papillomavirus vaccination in the COVID-19 Era. J Adolesc Health. 2020 Nov;67(5):633–4. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.013.

- LexJuris Puerto Rico. Ordenes Ejecutivas por el Coronavirus (COVID-19). 2022 [accessed 2022 Jun 26]. https://www.lexjuris.com/Ordenes/Index.htm.

- Goverment of Puerto Rico. Executive order of the governor of Puerto Rico, Hon. Pedro R. Pierluisi, to direct every public agency to require their employees to receive a COVID-19 vaccines in order to work in person, and for other purposes related to safeguarding the public health and safety. OE-2021-0582021.

- Goverment of Puerto Rico. Executive order of the governor of Puerto Rico, Hon. Pedro R. Pierluisi, to require the contractors of the executive branch, and the health and lodging sectors to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. OE-2021-0622021.

- Goverment of Puerto Rico. Executive order of the governor of Puerto Rico, Hon. Pedro R. Pierluisi, to implement varios initiatives against COVID-19, and to repeal administrative bulletins Nos. OE-2021-058, OE-2021-062, OE-2021,063, and OE-2021-064. OE-2021-0752021.

- Goverment of Puerto Rico. Executive order of the governor of Puerto Rico, Hon. Pedro R. Pierlluisi, in order to require a COVID-19 booster shot for students, the lodging sector, theaters, movie theaters, coliseums, convention and activity centers. OE-2022-0032022.

- Departamento de Salud. COVID-19 en cifras en Puerto Rico. Updated 2022 May 5th [accessed 2022 May 5th]. https://www.salud.gov.pr/estadisticas_v2#resumen.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. [accessed 2022 Jul 22]. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations_vacc-people-additional-dose-totalpop.

- Daniels V, Saxena K, Roberts C, Kothari S, Corman S, Yao L, Niccolai L. Impact of reduced human papillomavirus vaccination coverage rates due to COVID-19 in the United States: a model based analysis. Vaccine. 2021 May 12;39(20):2731–5. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.04.003.

- Gountas I, Favre-Bulle A, Saxena K, Wilcock J, Collings H, Salomonsson S, Skroumpelos A, Sabale U. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HPV vaccinations in Switzerland and Greece: road to recovery. Vaccines. 2023;11(2):258. doi:10.3390/vaccines11020258.

- Wähner C, Hübner J, Meisel D, Schelling J, Zingel R, Mihm S, Wölle R, Reuschenbach M. Uptake of HPV vaccination among boys after the introduction of gender-neutral HPV vaccination in Germany before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infection. 2023 Feb 10;2023. doi:10.1007/s15010-023-01978-0.

- Turner K, Brownstein NC, Whiting J, Arevalo M, Vadaparampil S, Giuliano AR, Islam JY, Meade CD, Gwede CK, Kasting ML, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among a national sample of United States adults ages 18–45: a cross-sectional study. Prev Med Rep. 2023 Feb 1;31:102067. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.102067.

- Ryan G, Gilbert PA, Ashida S, Charlton ME, Scherer A, Askelson NM. Challenges to adolescent HPV vaccination and implementation of evidence-based interventions to promote vaccine uptake during the COVID-19 pandemic: “HPV is probably not at the top of our list”. Prev Chronic Dis. 2022;19. doi:10.5888/pcd19.210378.

- López-Cepero A, Cameron S, Negrón LE, Colón-López V, Colón-Ramos U, Mattei J, Fernández-Repollet E, Pérez CM. Uncertainty and unwillingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine in adults residing in Puerto Rico: assessment of perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(10):3441–9. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1938921.

- Betsch C, Brewer NT, Brocard P, Davies P, Gaissmaier W, Haase N, Leask J, Renkewitz F, Renner B, Reyna VF, et al. Opportunities and challenges of Web 2.0 for vaccination decisions. Vaccine. 2012 May 28;30(25):3727–33. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.025.

- Puri N, Coomes EA, Haghbayan H, Gunaratne K. Social media and vaccine hesitancy: new updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(11):2586–93. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1780846.

- Center for Informed Democracy & Social Cybersecurity. A project tracking PA vaccine conversations and misinformation on Twitter. [accessed 2022 Jul 22]. https://www.cmu.edu/ideas-social-cybersecurity/research/pa-vaccine-hesitancy-project.html.

- Lu L, Liu J, Yuan YC, Burns KS, Lu E, Li D. Source trust and COVID-19 information sharing: the mediating roles of emotions and beliefs about sharing. Health Educ Behav. 2021;48(2):132–9. doi:10.1177/1090198120984760.

- Altman JD, Miner DS, Lee AA, Asay AE, Nielson BU, Rose AM, Hinton K, Poole BD. Factors affecting vaccine attitudes influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccines. 2023;11(3):516. doi:10.3390/vaccines11030516.

- Cunningham RM, Kerr GB, Orobio J, Munoz FM, Correa A, Villafranco N, Monterrey AC, Opel DJ, Boom JA. Development of a Spanish version of the parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019 May 4;15(5):1106–10. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1578599.

- Ipsos. Topline and methodology. 2020. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-12/topline-axios-wave-33.pdf.

- Suárez E, Pérez CM, Rivera R, Martínez MN. Applications of regression models in epidemiology. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons; 2017.

- Center for Disease Control Prevention. HPV vaccination recommendations. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/recommendations.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV vaccine. [accessed 2022 Jul 20]. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/vaccine-for-hpv.html.

- Sprengholz P, Felgendreff L, Böhm R, Betsch C. Vaccination policy reactance: predictors, consequences, and countermeasures. J Health Psychol. 2022;27(6):1394–407. doi:10.1177/13591053211044535.

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021 Feb 1;27(2):225–8. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9.

- Latkin CA, Dayton L, Yi G, Konstantopoulos A, Boodram B. Trust in a COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S.: a social-ecological perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2021 Feb;270:113684. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113684.

- Departamento de Salud. Vacunacion COVID-19: ordenes administrativas. [accessed 2022 Jul 22]. https://www.vacunatepr.com/%C3%B3rdenes-administrativas.

- Telemundo PR. Representante de Proyecto Dignidad levanta bandera sobre vacunación compulsoria. https://www.telemundopr.com/noticias/puerto-rico/representante-de-proyecto-dignidad-levanta-bandera-sobre-vacunacion-compulsoria/2239227/.

- Personas “antivacuna” protestan en centro de vacunación de Plaza las Américas. NotiCentrotv. https://www.wapa.tv/noticias/locales/personas–antivacuna–protestan-en-centro-de-vacunacion-de-plaza-las-americas_20131122518858.html.

- Se manifiestan en el Capitolio contra la vacunación compulsoria. Telemundo PR. https://www.telemundopr.com/noticias/puerto-rico/se-manifiestan-en-el-capitolio-contra-la-vacunacion-compulsoria/2239743/.

- Pares Arroyo M. Apelativo determina que el gobernador no puede emitir órdenes que regulen la conducta. Endi. https://www.elnuevodia.com/noticias/locales/notas/apelativo-determina-que-el-gobernador-no-puede-emitir-ordenes-que-regulen-la-conducta/.

- Departamento de Salud. COVID-19. [accessed 2022 Jul 22]. https://www.salud.gov.pr/CMS/142.

- VocesPR. Galeria vacunaciones COVID-19. 2022 Jul 22 [accessed 2022 Jul 22]. https://www.vocespr.org/galeriavacunacionescovid19.

- Burgos Gonzalez B. Se esperan variantes de COVID-19 más difíciles de tratar, aseguran destacados científicos del País. [accessed 2022 Jul 22]. https://medicinaysaludpublica.com/noticias/covid-19/se-esperan-variantes-de-covid19-mas-dificiles-de-tratar-aseguran-destacados-cientificos-del-pais/11239.

- Pares Arroyo M. La vacunación masiva: el arma perfecta en la lucha contra el COVID-19. [accessed 2022 Jul 22].

- Instrucción Pastoral sobre la importancia moral de vacunarse contra el COVID-19 (VERSIÓN COMPLETA). 2021. http://ceppr.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/CEP-INSTRUCCION-PASTORAL-SOBRE-LA-IMPORTANCIA-MORAL-DE-VACUNACION-CONTRA-COVID-19.pdf.

- Paul E, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: implications for public health communications. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021 Feb;1:100012. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012.

- Cordina M, Lauri MA. Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination, vaccine hesitancy and intention to take the vaccine. Pharm Prac (Granada). 2021;19(1):2317. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2021.1.2317.

- Alemán-Reyes AG, Díaz-Rivera E, Rodríguez-Quiñones AJ, Molina-Pérez XS, Oquendo-Claudio GI, Vega A, Colón-Díaz M. Correlation between parental vaccine hesitancy, socio-demographic factors, and novel SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in Puerto Rico. P R Health Sci J. 2022;41:185–91.

- He K, Mack WJ, Neely M, Lewis L, Anand V. Parental perspectives on immunizations: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on childhood vaccine hesitancy. J Community Health. 2022 Feb 1;47(1):39–52. doi:10.1007/s10900-021-01017-9.

- Almuzaini Y, Alsohime F, Subaie SA, Temsah M, Alsofayan Y, Alamri F, Alahmari A, Alahdal H, Sonbol H, Almaghrabi R, et al. Clinical profiles associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection and complications from coronavirus disease-2019 in children from a national registry in Saudi Arabia. Ann Thorac Med. 2021 Jul-Sep;16(3):280–6. doi:10.4103/atm.atm_709_20.

- Temsah M-H, Alhuzaimi AN, Aljamaan F, Bahkali F, Al-Eyadhy A, Alrabiaah A, Alhaboob A, Bashiri FA, Alshaer A, Temsah O, et al. Parental attitudes and hesitancy about COVID-19 vs. routine childhood vaccinations: a national survey. Original research. Front Public Health. 2021 Oct 13;9. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.752323.

- Alsubaie SS, Gosadi IM, Alsaadi BM, Albacker NB, Bawazir MA, Bin-Daud N, Almanie WB, Alsaadi MM, Alzamil FA. Vaccine hesitancy among Saudi parents and its determinants. Result from the WHO SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy survey tool. Saudi Med J. 2019 Dec;40(12):1242–50. doi:10.15537/smj.2019.12.24653.

- Gallant AJ, Nicholls LAB, Rasmussen S, Cogan N, Young D, Williams L. Changes in attitudes to vaccination as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study of older adults in the UK. PLoS One. 2021;16(12):e0261844. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0261844.

- Kessels SJM, Marshall HS, Watson M, Braunack-Mayer AJ, Reuzel R, Tooher RL. Factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake in teenage girls: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012 May 21;30(24):3546–56. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.063.