ABSTRACT

COVID-19 vaccination is effective for cancer patients without safety concerns. However, COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy is common among cancer patients. This study investigated factors affecting primary COVID-19 vaccination series completion rate among cancer patients in China. A multicentre cross-sectional study was conducted in four Chinese cities in different geographic regions between May and June 2022. A total of 893 cancer inpatients provided written informed consent and completed the study. Logistic regression models were fitted. Among the participants, 58.8% completed the primary COVID-19 vaccination series. After adjusting for background characteristics, concerns about interactions between COVID-19 vaccination and cancers/cancer treatment (adjusted odds ratios [AOR]: 0.97, 95%CI: 0.94, 0.99) were associated with lower completion of primary vaccination series. In addition, perceived higher risk of COVID-19 infection comparing to people without cancers (AOR: 0.46, 95%CI: 0.24, 0.88), perceived a high chance of having severe consequences of COVID-19 infection (AOR: 0.68, 95%CI: 0.51, 0.91) were also associated with lower completion rate. Being suggested by significant others (AOR: 1.32, 95%CI: 1.23, 1.41) and perceived higher self-efficacy to receive COVID-19 vaccination (AOR: 1.48, 95%CI: 1.31, 1.67) were positively associated with the dependent variable. Completion rate of primary COVID-19 vaccination series was low among Chinese cancer patients. Given the large population size and their vulnerability, this group urgently needs to increase COVID-19 vaccination coverage. Removing concerns about interactions between COVID-19 vaccination and cancers, using fear appeal approach, involving significant others, and facilitating patients to make a plan to receive COVID-19 vaccination might be useful strategies.

Introduction

Globally, cancer is the second leading cause of death. In 2020, the number of newly diagnosed cases and deaths of cancer was 18.1 and 10 million worldwide, and China accounted for 24% of these newly diagnosed cases and 30% of cancer-related deaths.Citation1–3 Retrospective cohort study of adults with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) showed that having metastatic solid tumors was associated with higher odds of mortality with COVID-19.Citation4,Citation5 As compared to people without cancers, cancer patients have been observed to be at higher risk of COVID-19 infection due to the immunosuppressed status caused by the malignancy and cancer treatments (e.g., chemotherapy and surgery).Citation6–8 Previous studies consistently showed that cancer patients, especially those with lung cancer, hematological cancer, metastatic cancer, or recent cancer treatment, were observed to have worse clinical outcomes after COVID-19 infection comparing to those without cancers.Citation6,Citation7,Citation9–11 For instance, studies showed that cancer patients with COVID-19 had a higher risk of hospitalization and death comparing to COVID-19 patients without cancers.Citation7,Citation11 Moreover, some cancer patients have delayed cancer treatments due to health anxieties associated with high risk and severe outcomes of COVID-19 infection and their desire to avoid exposure to COVID-19.Citation12 Such a phenomenon might negatively affect their cancer prognosis.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated high immunogenicity from COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancers, with better results for solid tumors than hematological malignancies, and with a good safety profile.Citation13 Given their high vulnerability to COVID-19 and the promising vaccine efficacy, cancer patients are considered as a priority group to receive the COVID-19 vaccination.Citation14 The World Health Organization (WHO and other international health authorities consistently recommend COVID-19 vaccination for all cancer patients.Citation15–21 However, cancer patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation and/or cellular therapy, and those with hematologic and/or solid tumor malignancies, should postpone vaccination until their treatment is completed.Citation16 In China, the National Guideline for COVID-19 vaccination (third edition) listed lymphoma and leukemia as contraindications.Citation22 Other people with solid tumors who are not on immunotherapy, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy are recommended to receive the inactivated, subunit, or recombinant COVID-19 vaccination.Citation22,Citation23 The guideline also highlighted that patients receiving immunotherapy, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy should receive the COVID-19 vaccination after completing these treatments.Citation22,Citation23

COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy is common among cancer patients. The prevalence of willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccination among cancer patients ranged from 17.9% in Hong Kong, China,Citation24 44.2% in Ethiopia,Citation25 53.7% in France,Citation26 55% in Lebanon,Citation27 60.3% in Poland,Citation28 to 61.8% in Korea.Citation29 As compared to studies among the general population in these countries during the same period, cancer patients had a much lower willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination.Citation30–33 In Ethiopia, a study reported that only 14.5% of cancer patients had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccination.Citation25 However, no study reported the COVID-19 vaccination uptake among cancer patients in mainland China.

Studies suggested the immune responses and vaccine efficacy in cancer patients was lower among cancer patients than the general population.Citation13,Citation34 Compared to healthy adults, there is less evidence of vaccine safety among cancer patients.Citation16,Citation21,Citation35 Therefore, cancer patients may be more concerned about the interactions between COVID-19 vaccination and cancers/cancer treatments, such as worrying about cancers leading to poorer vaccine efficacy, shorter duration of protection, and more severe side effects. However, no study has investigated whether such concerns are barriers of COVID-19 vaccination uptake among cancer patients. Previous studies also suggested that being male, older age, history of seasonal influenza, overweight or obese, receiving cancer treatment, perceived severe consequences of COVID-19, perceived more benefits of COVID-19 vaccination, and receiving suggestions made by physicians were facilitators to receive COVID-19 vaccination among cancer patients,Citation24–26,Citation28,Citation29 while concerns about vaccine safety and side effects, depression, and anxiety were barriers to receive such vaccination.Citation24,Citation26,Citation28,Citation29 These factors were also considered by this study.

In addition, exposure to information related to COVID-19 vaccination influenced people’s decision to take up such vaccines.Citation36 Thoughtful consideration of the veracity of information may mitigate the negative impact of misinformation related to COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination.Citation37,Citation38 To our knowledge, no study investigated the influence of information exposure or thoughtful consideration of the veracity of exposed information on COVID-19 vaccination uptake among cancer patients.

To fill the abovementioned knowledge gaps, this study was to investigate factors affecting completion of primary COVID-19 vaccination series among cancer inpatients in four Chinese cities in different geographic regions. We examined the effects of following factors: sociodemographic factors, perceptions and media exposure related to COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination.

Materials and methods

Study design

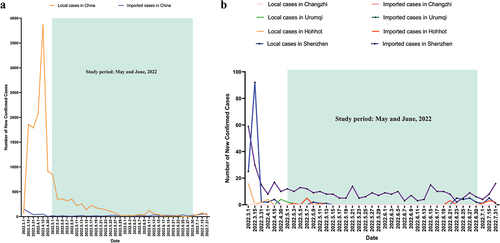

This is a multicentre cross-sectional survey conducted between May and June 2022. The study sites covered four conveniently selected Chinese cities, including one in the North (Changzhi), one in the Northeast (Hohhot), one in the West (Urumqi), and one in the South (Shenzhen). During the study period, all study sites followed the national guideline.Citation22 The situation of COVID-19 in China during the study period was shown in .

Participants

The inclusion criteria of the study participants were: 1) cancer patients who were hospitalized in the four participating hospitals during the study period, 2) aged 18 years or above, and 3) willing to provide written informed consent to complete the survey. Exclusion criteria applied to patients: 1) critical illness or intensive care unit admission, 2) with a diagnosis of lymphoma, leukemia, mental illness, or who were taking medication for mental illness, or 3) were diagnosed with dementia or unable to communicate effectively with the investigators. Physicians confirmed the first two inclusion and all exclusion criteria based on their medical records. We excluded patients with lymphoma or leukemia because both types of cancers were listed as contraindications of COVID-19 vaccination during the study period.Citation22

Recruitment and data collection

Medical staff in the participating hospitals approached all cancer inpatients, screened their eligibility, briefed them about the study, and invited them to complete a face-to-face interview. We approached all 1325 cancer inpatients during the study period, 1018 were eligible for the study, 125 refused to participate, and 893 provided written informed consent and completed the interview. The main reasons for refusal were lack of time and/or other logistic reasons (n = 90) and lack of interest in joining the study (n = 35). The overall response rate was 87.7% (79.0% in Hohhot, 80.1% in Changzhi, 94.3% in Shenzhen, and 97.6% in Urumqi). The recruitment procedures were shown in . No incentives were given to the participants.

Sample size planning

The target sample size was 800. We used “tests for two proportions” function in the PASS software. Among the 800 participants, we assumed 50% of them (n = 400) did not have a facilitating condition and the completion rate of primary vaccination series to be 10–40%. We input these parameters into the PASS and the results showed that such sample size could detect a smallest odds ratio of 1.49 between people with and without such facilitating condition (power: 0.80; alpha: 0.05; PASS11.0, NCSS LLC).

Ethical considerations

Prospective participants were informed that the survey was anonymous, their information would be kept strictly confidential, and they had the right to refuse to participate or withdraw from the study at any time. Refusal and withdrawal would not affect their access to any services. Written informed consent was obtained. This study was conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Changzhi Medical College (reference: RT2022027, date of approval: May 18, 2022).

Measurements

Development of the questionnaire

We performed in-depth interview to understand cancer patients’ perspective of COVID-19 vaccination. Ten cancer inpatients were purposively recruited in a participating hospital. With written informed consent, interviews were conducted by medical staff and audio recorded. We transcribed interviews and kept a code book to record special data and transform the data into categories to identify main themes. We identified three themes related to the barriers: 1) concerns that COVID-19 vaccination would be less effective, and with shorter protection period and more side effects for cancer patients, 2) concerns that cancer treatment would reduce effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination, and 3) concerns about COVID-19 vaccination would negatively affect cancer treatment. Three other themes were related to the facilitators. They were: 1) perceived high risk of COVID-19, 2) cancer patients were more likely to have severe consequences following COVID-19 infection, and 3) suggestions made by doctors and family members. Based on the findings and literature review, a panel of epidemiologists, behavioral health experts, health psychologists, and oncologists developed the questionnaire. The questionnaire was tested among 20 cancer inpatients to assess clarity and readability. All participants in the pilot study agreed that the questions were easy to understand and the length was acceptable. These cancer inpatients did not participate in the actual survey. The panel finalized the questionnaire based on their comments.

Background characteristics

Participants reported sociodemographic characteristics, including age, gender, ethnicity, education level, relationship status, and employment status. The medical staff extracted cancer-related characteristics from their medical records, including type and current treatment of cancers, and the presence of metastatic cancers. Presence of other chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension/hyperlipidemia, and other chronic diseases) were also extracted from their medical record.

COVID-19 vaccination uptake

The number of doses of COVID-19 vaccination received by the participants was extracted from their vaccination records. We defined completion of the primary COVID-19 vaccination series as receiving at least two doses of COVID-19 vaccination. We used a checklist to assess local adverse events (pain, redness, itching, swelling, induration, and skin rashes in the arm where the shot was given) and systematic adverse events (abnormal skin and mucosa, diarrhea, anorexia, vomit, nausea, muscle/joint pain, headache, cough, fatigue, fever, and others) within one month after receiving COVID-19 vaccination. The same checklist was used to measure self-reported adverse events of COVID-19 vaccination among general populationCitation39 and diabetic patients in China.Citation40

Perceptions related to COVID-19 vaccination

We measured perceptions related to COVID-19 vaccination based on the Health Belief Model (HBM).Citation41 Five items were constructed to measure concerns related to potential interactions between cancer/cancer treatment and COVID-19 vaccination. These concerns were considered as barriers to receive COVID-19 vaccination in our in-depth interview of cancer patients. The Perceived Barrier Scale was formed by summing up individual item scores. The measurements of cue to action and perceived self-efficacy were adapted from scale/item validated in the Chinese population.Citation37,Citation42 The response categories for these measurements were 1 = disagree, 2 = neutral, and 3 = agree. The Cronbach’s alpha of the Perceived Barrier Scale and the Cue to Action Scale were 0.92 and 0.89, respectively.

In addition, four items measured perceived susceptibility and perceived severity. Two items asked the participants to compare their risk of COVID-19 and chance of having severe consequences if contracting COVID-19 versus people without cancers (response categories: 1= much lower, 2 = somewhat lower, 3 = similar, 4 = somewhat higher, & 5 = much higher). Two other items measured their chance of contracting the Omicron variant of COVID-19 and having severe consequences if contracting COVID-19 (response categories: 1 = low, 2 = moderate, 3 = high, & 4 = uncertain).

Media influences related to COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination

Items measuring the frequency of exposure to topics related to COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination were adapted from validated measurements in the Chinese population.Citation37 The topics included infectivity of the Omicron variant of COVID-19, the relatively low risk of having severe consequences or death after infecting Omicron variant of COVID-19, COVID-19 pandemic was not under control after COVID-19 vaccination rollout, and people contracting COVID-19 after completing primary vaccination series (response categories: 1 = almost never, 2 = seldom, 3 = sometimes, & 4 = always). A validated item measured the frequency of thoughtful consideration about the veracity of COVID-19-specific information.Citation43

Statistical analysis

The frequency distribution of all study variables were presented. Mean and standard deviation (SD) of the item and/or scale scores representing perceptions and media influence were also presented. Cronbach’s alpha for the scales was calculated using the “reliability analysis” in the SPSS. Cronbach’s alpha is a measure to assess the reliability, or internal consistency, of a set of scale or test item. We performed exploratory factor analysis using principal component analysis with varimax rotation. The dependent variable was the completion of the primary COVID-19 vaccination series. We first assessed the significance between background characteristics and the dependent variable using univariate logistic regression models. Perceptions and media influence were independent variables of interest. We fitted a single logistic regression model to obtain adjusted odds ratios (AOR), which involved one of these independent variables of interest and all significant background variables in univariate analysis. There were no missing values for the participants who completed the survey. SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp) was used for data analysis, with P < .05 considered as statistically significant.

Results

Background characteristics

About half of the participants were over 60 years old (45.1%) and female (45.6%). The majority of the participants were the Han majority (83.2%), married (91.4%), did not receive tertiary education (85.7%), and without afull-time work (79.8%). The most common type of cancer among the participants was lung cancer (24.0%), followed by colorectal cancer (16.2%) and gastric cancer (11.6%). At the time of this study, most of the participants were under cancer treatment (93.5%); 6.5% had metastatic cancers. In addition to cancers, 18.6% of the participants had at least one other chronic conditions ().

Table 1. Background characteristics of the participants (n = 893).

COVID-19 vaccination uptake

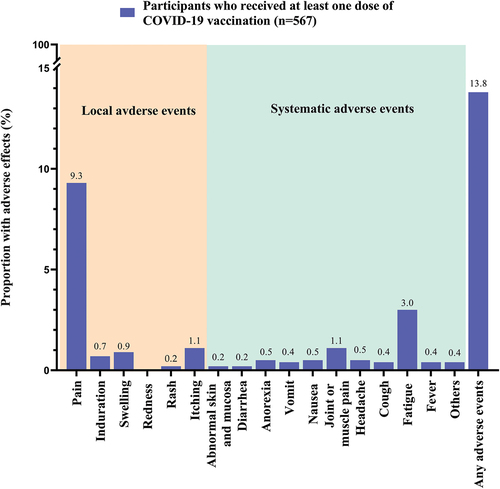

Among the participants, 29.5% received two doses of COVID-19 vaccination, and 29.3% received the third dose. The proportion of completing the primary COVID-19 vaccination series was 58.8% (95%CI, 55.5–62.0%) (). Among participants who received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccination (n = 567), 97.7% (n = 554) completed their last dose in the past year (≤6 months: 49.2%; 7–12 months: 48.5%). Among vaccinated participants, 13.8% reported having some side effects. The most common side effects was pain in the injection site (n = 53, 9.3%), followed by fatigue (n = 17, 3.0%), muscle/joint pain (n = 6, 1.1%) and itching in the injection site (n = 6, 1.1%). Most of the reported side effects were mild ().

Table 2. COVID-19 vaccination uptake, perceptions and media influences related to COVID-19 vaccination (n = 893).

Perceptions and media influence related to COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination

About 40% of the participants were concerned that COVID-19 vaccination would have weaker protection, shorter protection duration and more side-effects among cancer patients. A similar proportion of participants perceived cancer therapy would reduce effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination, and COVID-19 vaccination would negatively affect cancer control. About half of the participants perceived a higher risk of COVID-19 infection (44.5%) and more severe consequences of COVID-19 infection comparing to people without cancers (45.6%). Item responses and scale scores of other perceptions related to COVID-19 vaccination were shown in . Regarding media influence, 43.8% of the study participants were always exposed to information about the infectivity of the Omicron variant of COVID-19 on TV, radio, newspaper, and the internet. Relatively few participants were exposed to other topics through these channels. Only 17.5% of the participants always considered the veracity of COVID-19-specific information ()

Factors associated with completion of primary COVID-19 vaccination series

In univariate analysis, participants who were older and without a full-time work had lower completion of primary vaccination series. Receiving tertiary education and presence of chronic conditions other than cancers were positively associated with the dependent variable. As compared to those with lung cancers, people having gastric cancers, colorectal cancer and other cancers were more likely to complete the primary vaccination series, while those with breast cancers had a lower completion rate ().

Table 3. Associations between background characteristics and completion of primary COVID − 19 vaccination series among cancer patients (n = 893).

After adjustment for significant background characteristics, participants who perceived a higher risk of COVID-19 infection than people without cancers did (AOR: 0.46, 95%CI:0.24, 0.88), and a high chance of having severe consequences if contracting COVID-19 (AOR: 0.68, 95%CI: 0.51, 0.91) were less likely to complete the primary vaccination series. A significant and negative association was also found between perceived barriers to receive COVID-19 vaccination and the dependent variable (AOR: 0.97, 95%CI: 0.94, 0.99). Being suggested by significant others (AOR: 1.32, 95%CI: 1.23, 1.41) and perceived self-efficacy to receive COVID-19 vaccination (AOR: 1.48, 95%CI: 1.31, 1.67) were positively associated with the dependent variable. Frequency of exposure to topics on different media channels and thoughtful consideration about the veracity of the information were not significantly associated with the dependent variable ().

Table 4. Factors associated with and completion of primary COVID-19 vaccination series among cancer patients (n = 893).

Discussion

This study was the first time to find that concerns about the interactions between COVID-19 vaccination and cancer/cancer treatment were barriers to receive COVID-19 vaccination among cancer patients. According to the principle of social marketing, health promotion should tailor to the needs of the target population. This study provided some practical implications to inform health promotion for cancer patients. We found a low COVID-19 vaccination uptake among our participants, as only 58.8% completed the primary vaccination series, and 29.3% received a booster dose. Although these figures were higher than that reported in Ethiopia (14.5%),Citation25 they were much lower than those of the general population in China. By March 2022, 90.47% of people in China had completed the primary COVID-19 vaccination series, and 48.9% received a booster dose.Citation44 Given the large population size of cancer patients in China and their vulnerability to the emerging variants of concerns, low COVID-19 vaccination coverage in this group would diminish the nation’s efforts to build a “great wall of immunization.”Citation44 There is hence a strong need to promote COVID-19 vaccination among cancer patients.

This study has numerous practical implications for developing vaccination promotion strategies for cancer patients. First, more attention should be given to older cancer patients who did not receive tertiary education, and were without full-time work. In contrast with studies targeting cancer patients in other countries,Citation29 older participants were less likely to complete the primary COVID-19 vaccination series in our study. Previous studies showed that older people in China had lower COVID-19 vaccination uptake compared to their younger counterparts.Citation42 China was recently hit by the Omicron variants of COVID-19 and most of the COVID-19 associated death occurred among older adults who had not completed the primary vaccination series.Citation45 Previous studies suggested that cancer and older age were two independent risk factors of COVID-19 mortality.Citation8,Citation46 Therefore, such information should be disseminated to cancer patients to increase their awareness. In this study, participants with a full-time work were more likely to complete the primary COVID-19 vaccine series. One possible explanation is that many local employers required their employees to receive COVID-19 vaccination. Lower education level was a barrier of COVID-19 vaccination uptake among cancer patients in this study. Therefore, health communication messages promoting COVID-19 vaccination for cancer patients should be straightforward and easy to understand by people with low literacy levels. Moreover, future programs promoting COVID-19 vaccination for cancer patients should be aware of the difference in vaccine hesitancy among people with various cancers. Focused attention should be given to patients with breast cancers and lung cancers as participants in this study with diagnosis of these cancers reported lower COVID-19 vaccination uptake. In addition, people with other chronic diseases reported higher COVID-19 vaccination uptake in this study. Participants with other chronic conditions may perceive that they are more vulnerable to COVID-19 and hence have higher motivation to use COVID-19 vaccination to protect themselves.

Second, removing concerns about interactions between COVID-19 vaccination and cancers/cancer treatments is potentially valuable for future programs, as these concerns were barriers to complete COVID-19 vaccination in this study. Recent evidence showed that in patients with past and active neoplasms, the BNT162b2 vaccine has similar efficacy and safety profiles as the general population.Citation47 In China, inactivated vaccines are in the most widespread in China (over 85% of all COVID-19 vaccine doses administered). However, there was a lack of evidence about the differences in efficacy and safety of inactivated COVID-19 vaccines between people with and without cancers. Such evidence is important to address cancer patients’ concerns about interactions between COVID-19 vaccination and cancers/cancer treatments and to support COVID-19 vaccination implementation for cancer patients. The mRNA vaccines are not yet available in China. Although the duration of protection might be shorter for cancer patients, recent evidence showed that the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine had similar vaccine efficacy and safety profiles among people with and without cancers.Citation34 Therefore, the country may consider introducing them for cancer patients. Furthermore, recent studies showed that receiving a COVID-19 vaccine booster dose could significantly increase antibody titers among cancer patients and many countries have been recommending a third and a fourth dose of COVID-19 vaccine to cancer patients.Citation48–50 Therefore, the country may also consider introducing a COVID-19 vaccine booster dose to cancer patients. Many regions have already recommended a third and fourth dose of COVID-19 vaccines to immunodeficiency people, such as cancer patients, including in Hong Kong, China.Citation51 In order to remove participants’ concerns about cancer treatment and COVID-19 vaccination. Health communication messages should emphasize that people undergoing active cancer treatments responded well to COVID-19 vaccination,Citation52 and no evidence shows that COVID-19 vaccination would affect cancer treatments.

Third, modifying other perceptions related to COVID-19 vaccination based on the HBM is potentially useful in future health promotion. Both perceived higher susceptibility and severity of COVID-19 were significantly associated with lower completion of primary vaccination series in this study. It was possible that cancer patients who completed the COVID-19 vaccination felt the vaccines were protecting them and hence perceived a lower risk and less severe consequences of COVID-19 infection. Our study was a cross-sectional survey and could not establish causal relationship. In our study, we measured relative (i.e., as compared to people without cancers) and absolute levels of perceived susceptibility and severity. Interestingly, the relative level of susceptibility and absolute level of severity were significantly associated with the COVID-19 vaccination completion, while the associations between the other two measurements and the dependent variable were non-significant. Our findings suggested that relative level of susceptibility and absolute level of severity was significantly associated with the COVID-19 vaccination completion. Therefore, health communication should increase relative level of susceptibility by emphasizing cancer patients have a higher risk of COVID-19 infection than people without cancers, and enhancing absolute level of severity by highlighting high risk of hospitalization and mortality among cancer patients following COVID-19 infection. In line with studies among cancer patients in other countries and among general population in China, being suggested by significant others to take up COVID-19 vaccination was a facilitator of completing primary vaccination series.Citation24–26,Citation28,Citation29 Future programs should involve physicians and family members of cancer patients to provide a solid cue to action to complete COVID-19 vaccination series. In addition, it is useful to increase perceived self-efficacy, as it was a facilitator to complete primary COVID-19 vaccination series and there was much room for improvement. Previous studies suggested some useful strategies to increase self-efficacy, such as informing cancer patients about suitable timing to receive COVID-19 vaccination and facilitating them to form a solid plan to receive the vaccination.Citation53

Fourth, in contrast to our hypothesis, exposure to information related to COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination through different media channels were not significantly associated with completing the primary vaccination series. Future health promotion should focus on modifying individual-level determinants (e.g., perceptions). Health promotion needs to be evidence-based.

The first strength of this study lies in being a multi-center study, hence the extrapolation of the research results is more representative. Secondly, this is the first application of the HBM used to explain COVID-19 vaccination uptake related factors, the results of this study theoretically point out the direction for carrying out targeted health education and behavioral intervention to improve the COVID-19 vaccination rate of tumor patients through the HBM model.

This study had some limitations. First, our findings are most applicable to the time when zero COVID policy was implemented in China. When China started to relieve its COVID-19 control measures, the number of COVID-19 cases increased dramatically and people might perceive a much higher risk of COVID-19 and hence a stronger need to get vaccinated. Second, adverse events of COVID-19 vaccination were self-reported and recall bias existed. Third, we only targeted inpatients and our findings could not be generalized to all cancer patients. Fourth, the study sites were selected conveniently and the sample could not represent all cancer patients in China. Fifth, we could not obtain the characteristics of cancer patients who refused to join the study. These patients might have different characteristics as compared to study participants and selection bias existed. However, the magnitude of selection bias might be limited as our response rate was quite high. Moreover, we did not include the perceived benefit of COVID-19 vaccination, a facilitator of vaccination uptake among cancer patients in previous studies, due to the limited length of the questionnaire. Furthermore, this was a cross-sectional survey and could not establish causal relationship.

In conclusion, we found a low completion rate of primary COVID-19 vaccination series among cancer patients in China. Given the large population size and their vulnerability to COVID-19, there is an urgent need to increase COVID-19 vaccination coverage among cancer patients in China. The findings of our study indicated that removing concerns about interaction between COVID-19 vaccination and cancers/cancer treatments, using fear appeal approach, involving significant others, and facilitating patients to make a plan to receive COVID-19 vaccination would be useful strategies.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Z.W., J.X.; methodology: L.Z., R.S., J.Y., Z.W., J.X.; data curation: L.Z., R.S., J.Y., X.D., Y.W.; project administration: L.Z., R.S., J.Y., X.D., Y.W.; writing-original draft preparation: S.C., P.S-f.C., Z.W.; writing-review and editing: S.C., P.S-f.C., Z.W., J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional review board statement

This study was conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Changzhi Medical College (reference: RT2022027, date of approval: May 18, 2022).

Informed consent statement

Prospective participants were informed that the survey was anonymous, their information will be kept strictly confidential, and they had the right to refuse to participate or withdraw from the study at any time. Refusal and withdrawal would not affect their access to any services. Written informed consent was obtained.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as they contain sensitive personal behaviors but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sikkema KJ, Abler L, Hansen NB, Wilson PA, Drabkin AS, Kochman A, MacFarlane JC, DeLorenzo A, Mayer G, Watt MH, et al. Positive choices: outcomes of a brief risk reduction intervention for newly HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1808–12. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0782-3.

- Carrico AW, Nation A, Gómez W, Sundberg J, Dilworth SE, Johnson MO, Moskowitz JT, Rose CD. Pilot trial of an expressive writing intervention with HIV-Positive methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;29(2):277–82. doi:10.1037/adb0000031.

- Cao W, Chen H-D, Yu Y-W, Li N, Chen W-Q. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134(7):783–91. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000001474.

- Harrison SL, Fazio-Eynullayeva E, Lane DA, Underhill P, Lip GYH. Comorbidities associated with mortality in 31,461 adults with COVID-19 in the United States: a federated electronic medical record analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(9):e1003321. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003321.

- Rosenthal N, Cao Z, Gundrum J, Sianis J, Safo S. Risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality in a US national sample of patients with COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2029058. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29058.

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K, Li C, Ai Q, Lu W, Liang H, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–7. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6.

- Wang QQ, Berger NA, Xu R. Analyses of risk, racial disparity, and outcomes among US patients with cancer and COVID-19 infection. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):220–7. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6178.

- Dai M, Liu D, Liu M, Zhou F, Li G, Chen Z, Zhang Z, You H, Wu M, Zheng Q, et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2: a multicenter study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(6):783–91. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0422.

- Rugge M, Zorzi M, Guzzinati S. SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Italian Veneto region: adverse outcomes in patients with cancer. Nat Cancer. 2020;1(8):784–8. doi:10.1038/s43018-020-0104-9.

- Joharatnam-Hogan NN, Daniel Hochhauser D, Shiu K-K, Rush H, Crolley V, Butcher E, Sharma A, Muhammad A, Vasdev N, Anwar M, et al. LBA83 outcomes of the 2019 novel coronavirus in patients with or without a history of cancer: a multi-centre North London experience. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S1209–S1209. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.2324.

- Meng YF, Lu W, Guo E, Liu J, Yang B, Wu P, Lin S, Peng T, Fu Y, Li F, et al. Cancer history is an independent risk factor for mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a propensity score-matched analysis. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1). doi:10.1186/s13045-020-00907-0.

- Fujita K, Ito T, Saito Z, Kanai O, Nakatani K, Mio T. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on lung cancer treatment scheduling. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11(10):2983–6. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.13615.

- Cavanna L, Citterio C, Toscani I. COVID-19 vaccines in cancer patients. Seropositivity and safety. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(9):1048. doi:10.3390/vaccines9091048.

- American Cancer Society. COVID-19 vaccines in people with cancer. [accessed 2023 May 12]. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/managing-cancer/coronavirus-covid-19-and-cancer/covid-19-vaccines-in-people-with-cancer.html.

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 advice for the public: getting vaccinated. 2022. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines/advice.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Recommendations of the national comprehensive cancer network® (NCCN®) advisory committee on COVID-19 vaccination and pre-exposure prophylaxis*. 2022. https://www.nccn.org/docs/default-source/covid-19/2021_covid-19_vaccination_guidance_v5-0.pdf?sfvrsn=b483da2b_114.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer survivors-staying well during COVID-19. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/survivors/staying-well-during-covid-19.htm.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Vaccines-efficacy, effectiveness and duration of immunity - EU/EEA authorised COVID-19 vaccines. 2022. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/latest-evidence/vaccines.

- Gauci ML, Coutzac C, Houot R, Marabelle A, Lebbé C. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for cancer patients treated with immunotherapies: recommendations from the French society for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer (FITC). Eur J Cancer. 2021;148:121–3. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.02.003.

- Garassino MC, Vyas M, de Vries EGE, Kanesvaran R, Giuliani R, Peters S. The ESMO call to action on COVID-19 vaccinations and patients with cancer: vaccinate. Monitor. Educate. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(5):579–81. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.068.

- European Society of Medical Oncology. ESMO statements on vaccination against COVID-19 in people with cancer. 2022. https://www.esmo.org/covid-19-and-cancer/covid-19-vaccination.

- Heilongjiang Province People’s Government. COVID-19 vaccination (Third Edition). 2022 [accessed 2022 June 28]. https://www.hlj.gov.cn/n200/2021/0908/c988-11022120.html.

- 徐若男, 聂建云, 王涛, 李健斌, 殷咏梅, 王晓稼, 耿翠芝, 宋尔卫, 江泽飞, 王福生. 乳腺癌患者新冠疫苗接种中国专家共识. 传染病信息. 2021;34(6):481–4.

- Chan W-L, Ho YHT, Wong CKH, Choi HCW, Lam K-O, Yuen K-K, Kwong D, Hung I. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination in cancer patients in Hong Kong: approaches to improve the vaccination rate. Vaccines. 2021;9(7):792. doi:10.3390/vaccines9070792.

- Tadele Admasu F. Knowledge and proportion of COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors among cancer patients attending public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021: a multicenter study. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:4865–76. doi:10.2147/IDR.S340324.

- Barrière J, Gal J, Hoch B, Cassuto O, Leysalle A, Chamorey E, Borchiellini D. Acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among French patients with cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(5):673–4. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.066.

- Moujaess E, Zeid NB, Samaha R, Sawan J, Kourie H, Labaki C, Chebel R, Chahine G, Karak FE, Nasr F, et al. Perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine among patients with cancer: a single-institution survey. Future Oncol. 2021;17(31):4071–9. doi:10.2217/fon-2021-0265.

- Brodziak A, Sigorski D, Osmola M, Wilk M, Gawlik-Urban A, Kiszka J, Machulska-Ciuraj K, Sobczuk P. Attitudes of patients with cancer towards vaccinations—results of online survey with special focus on the vaccination against COVID-19. Vaccines. 2021;9(5):411. doi:10.3390/vaccines9050411.

- Chun JY, Kim SI, Park EY, Park S-Y, Koh S-J, Cha Y, Yoo HJ, Joung JY, Yoon HM, Eom BW, et al. Cancer patients’ willingness to take COVID-19 vaccination: a nationwide multicenter survey in Korea. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(15):3883. doi:10.3390/cancers13153883.

- Wong MCS, Wong ELY, Huang J, Cheung AWL, Law K, Chong MKC, Ng RWY, Lai CKC, Boon SS, Lau JTF, et al. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: a population-based survey in Hong Kong. Vaccine. 2021;39(7):1148–56. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.083.

- Abebe H, Shitu S, Mose A. Understanding of COVID-19 vaccine knowledge, attitude, acceptance, and determinates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among adult population in Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:2015–25. doi:10.2147/IDR.S312116.

- Gagneux-Brunon A, Detoc M, Bruel S, Tardy B, Rozaire O, Frappe P, Botelho-Nevers E. Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: a cross-sectional survey. J Hosp Infect. 2021;108:168–73. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.020.

- Bou Hamdan M, Singh S, Polavarapu M, Jordan TR, Melhem NM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among university students in Lebanon. Epidemiol Infect. 2021;149:e242. doi:10.1017/S0950268821002314.

- Lee LYW, Starkey T, Ionescu MC, Little M, Tilby M, Tripathy AR, Mckenzie HS, Al-Hajji Y, Barnard M, Benny L, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 breakthrough infections in patients with cancer (UKCCEP): a population-based test-negative case-control study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(6):748–57. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00202-9.

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. COVID-19 vaccination guidelines (First Edition). 2021. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqfkdt/202103/c2febfd04fc5498f916b1be080905771.shtml.

- Zhang KC, Fang Y, Cao H, Chen H, Hu T, Chen Y, Zhou X, Wang Z. Behavioral intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese factory workers: cross-sectional online survey. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(3):e24673. doi:10.2196/24673.

- Zhang K, Fang Y, Chan PSF, Cao H, Chen H, Hu T, Chen Y, Zhou X, Wang Z. Behavioral intention to get a booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine among Chinese factory workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9):5245. doi:10.3390/ijerph19095245.

- Singh A, Lai AHY, Wang J, Asim S, Chan PSF, Wang Z, Yeoh EK. Multilevel determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among South Asian Ethnic Minorities in Hong Kong: cross-sectional web-based survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7(11):e31707. doi:10.2196/31707.

- Huang X, Yan Y, Su B, Xiao D, Yu M, Jin X, Duan J, Zhang X, Zheng S, Fang Y, et al. Comparing immune responses to inactivated vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 between people living with HIV and HIV-Negative individuals: a cross-sectional study in China. Viruses. 2022:14(2). doi:10.3390/v14020277

- Xu J, Chen S, Wang Y, Duan L, Li J, Shan Y, Lan X, Song M, Yang J, Wang Z. Prevalence and determinants of COVID-19 vaccination uptake were different between Chinese diabetic inpatients with and without chronic complications: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(7):994. doi:10.3390/vaccines10070994.

- Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi:10.1177/109019818401100101.

- Wang Z, Fang Y, Yu F-Y, Chan PSF, Chen S. Governmental incentives, satisfaction with health promotional materials, and COVID-19 vaccination uptake among community-dwelling older adults in Hong Kong: a random telephone survey. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(5):732. doi:10.3390/vaccines10050732.

- Pan Y, Xin M, Zhang C, Dong W, Fang Y, Wu W, Li M, Pang J, Zheng Z, Wang Z, et al. Associations of mental health and personal preventive measure compliance with exposure to COVID-19 information during work resumption following the COVID-19 outbreak in china: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(10):e22596. doi:10.2196/22596.

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China.88.01% of people in China completed COVID-19 vaccination. 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 5]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-03/26/content_5681691.htm.

- The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Archive of statistics on 5th wave of COVID-19. statistics based on data up to 15 March 2022 00: 00. [accessed 2022 Mar 17]. https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/pdf/5th_wave_statistics/5th_wave_statistics_20220315.pdf.

- Kang SJ, Jung SI. Age-related morbidity and mortality among patients with COVID-19. Infect Chemother. 2020;52(2):154–64. doi:10.3947/ic.2020.52.2.154.

- Thomas SJ, Perez JL, Lockhart SP, Hariharan S, Kitchin N, Bailey R, Liau K, Lagkadinou E, Türeci Ö, Şahin U, et al. Efficacy and safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in participants with a history of cancer: subgroup analysis of a global phase 3 randomized clinical trial. Vaccine. 2022;40(10):1483–92. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.12.046.

- Wang Y, Zhang L, Chen S, Lan X, Song M, Su R, Yang J, Wang Z, Xu J. Hesitancy to receive the booster doses of COVID-19 vaccine among cancer patients in China: a multicenter cross-sectional survey — four PLADs, China, 2022. China CDC Wkly. 2023;5(10):223–8. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2023.041.

- Mai AS, Lee ARYB, Tay RYK, Shapiro L, Thakkar A, Halmos B, Grinshpun A, Herishanu Y, Benjamini O, Tadmor T, et al. Booster doses of COVID-19 vaccines for patients with haematological and solid cancer: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2022;172:65–75. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2022.05.029.

- Re D, Seitz-Polski B, Brglez V, Carles M, Graça D, Benzaken S, Liguori S, Zahreddine K, Delforge M, Bailly-Maitre B, et al. Humoral and cellular responses after a third dose of SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients with lymphoid malignancies. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):864. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28578-0.

- The Government of the Hong Kong SAR. COVID-19 vaccination programme. 2021 [accessed 2021 Mar 1]. https://www.covidvaccine.gov.hk/en/programme.

- Khan QJ, Bivona CR, Martin GA, Zhang J, Liu B, He J, Li KH, Nelson M, Williamson S, Doolittle GC, et al. Evaluation of the durability of the immune humoral response to COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer undergoing treatment or who received a stem cell transplant. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(7):1053–8. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.0752.

- Wu J, Xia Q, Miao Y, Yu C, Tarimo, CS, Yang Y. Self-perception and COVID-19 vaccination self-efficacy among Chinese adults: a moderated mediation model of mental health and trust. J Affect Disord. 2023;333:313–20. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.047.