?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Vaccine hesitancy is a significant public health issue globally. We aim to document the barriers toward seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among healthcare workers (HCWs) and pregnant women (PW) in Pakistan. We performed a concurrent mixed methods study in four cities (Karachi, Islamabad, Quetta, and Peshawar) across Pakistan from September to December 2021. The quantitative component consisted of independent cross-sectional surveys for PW and HCWs, and the qualitative component comprised of in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) among HCWs. Simple linear regression was used to determine the association of sociodemographic variables with knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Overall, 750 PW and 420 HCWs were enrolled. Among the PW, 44% were willing to receive the vaccine if available free of cost. Only 44% of the HCWs were vaccinated; however, 86% intended to get vaccinated and were willing to recommend the vaccine to their patients. HCWs refused vaccine due to side-effects (65%), cost (57%), and allergies (36%). An education level of secondary school and above was predictive of higher attitude and knowledge scores while having received the COVID-19 vaccine was associated with higher practice scores for both PW and HCWs. Several themes emerged from the interviews: 1) HCWs’ knowledge of influenza and its prevention, 2) HCWs’ perception of motivators and barriers to influenza vaccine uptake and 3) HCWs’ attitudes towrd vaccine promotion. We report low influenza vaccine coverage among HCWs and PW in Pakistan. Educational campaigns addressing misconceptions, and improving affordability and accessibility through government interventions, can improve vaccine uptake.

Introduction

Influenza is a viral respiratory infection that is endemic globally.Citation1 Approximately, 1 billion cases of influenza occur annually, with 3–5 million cases of severe illness resulting in 290,000–650,000 global deaths.Citation2 The risk of complications and disease severity is higher in certain vulnerable groups such as immunosuppressed patients, the elderly (>65 years), children younger than 5 years, and pregnant women. Despite the availability of antiviral drugs in the market, vaccination against influenza plays a crucial role in preventing flu-related morbidity, mortality, and economic consequences.Citation2 Globally, influenza vaccination has prevented about 7.5 million flu cases, 3.7 million medical visits, 105,000 hospitalizations, and 6,300 fatalities between 2019–2020.Citation3,Citation4 Currently, seasonal influenza vaccines are available in both inactivated and live attenuated forms, in either trivalent or quadrivalent formulations, and have efficacy estimates ranging from 16% to 76%.Citation2

Based on the established literature, the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) by the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends healthcare workers, pregnant women, children aged 6 to 59 months, the elderly and, persons with underlying chronic conditions as the priority groups to receive the seasonal influenza vaccine.Citation5 Despite these recommendations, vaccine coverage in the priority groups remains suboptimal in Pakistan and there is a lack of influenza vaccination policy at national level.Citation6 Vaccines are solely accessible through private markets, with the supply being sporadic and delayed, and individuals seeking vaccination must personally cover the associated costs.Citation6 Additionally, there exists a lack of clear understanding among the population regarding influenza-related complications, recommendations from healthcare providers, and safety concerns associated with vaccination during pregnancy.Citation6

Among the various high-risk groups, we find that pregnant women and healthcare workers are linked in terms of their healthcare seeking practices. Previous research has revealed 10 to 12 times greater odds of pregnant women receiving an influenza vaccination when they received a recommendation from their healthcare providers.Citation5,Citation7 Vaccination during pregnancy effectively prevents influenza in both pregnant women and their infants <6 months of age, who are ineligible for the vaccine.Citation8 The knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) model suggests that the behavior of healthcare workers is crucial as pregnancy-related practices often depend on their recommendations.Citation9 Previous literature has also shown that healthcare workers are more likely to recommend vaccination to pregnant if they would personally take the influenza vaccine themselves.Citation10 In addition, health professionals receiving immunization training were more confident advising pregnant women.Citation10

Thus, this study aims to document the enablers and barriers of seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among two priority groups, pregnant women, and healthcare workers in Pakistan.

Methods

Study design

We used a concurrent mixed methods approach to gain insight about seasonal influenza vaccination in Pakistan. The quantitative component consisted of independent cross-sectional surveys for pregnant women and HCWs while the qualitative component consisted of in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs). Both the data collection components were conducted simultaneously and independently of each other. Finally, the narrative qualitative information was triangulated with the quantitative findings, and final interpretative statements were made.

Quantitative component

We conducted community-based cross-sectional surveys in four cities (Karachi, Islamabad, Quetta, and Peshawar) across Pakistan from September to December 2021. We aimed to capture the diversity of the four major provinces of Pakistan in terms of their ethnicity, culture, and healthcare facilities across the provinces. Thus, we selected major cities from each province, in terms of their population size: Karachi (16,459,472), Lahore (13,095,166), Peshawar (2,272,812), and Quetta (1,129,361).Citation11

Since no specific sampling frame was available for pregnant women and healthcare workers in these cities, we used convenience sampling to gather data. We identified hospitals in the chosen cities and enrolled healthcare workers and pregnant women who were visiting these hospitals as participants in the study after obtaining written informed consent. The recruitment of pregnant women and healthcare workers took place at Polyclinic Hospital in Islamabad, Sandeman Hospital in Quetta, as well as Northwest General Hospital and Jinnah Medical College in Peshawar. In Karachi city, pregnant women were enrolled from a community site in Korangi District (Ibrahim-Hyderi) while HCWs were enrolled from the Aga Khan University Hospital and its affiliated secondary care hospitals.

Study tools

We collected quantitative data using separate standardized tools for PW and HCWs. The tools were adapted from a generic PIVI (The Partnership for Influenza Vaccine Introduction) survey tool by researchers at the Aga Khan University, Pakistan to suit local needs taking inputs from WHO EMRO experts and other research team members (supplemental file 1 and 2).Citation12 The questionnaire is pre-validated and previously tested for reliability and item selection and is being currently used in KAP studies by PIVI in Low-and Middle-Income countries (LMICs).Citation13 The study tool was designed to inquire about the demographic information of the healthcare workers (HCWs) and pregnant women (PW), their vaccination status, the reasons for not receiving the influenza vaccination, and the general knowledge of influenza disease and vaccines.

The HCW questionnaire had 37 questions which were divided into three sections. The first section comprised of 21 questions about the history, general knowledge and attitudes about influenza and influenza vaccines. The second section had three questions (question number 22–24) regarding the knowledge and attitudes about influenza and its vaccines in patient care and the third section asked about sociodemographic characteristics such as gender, age, employment status, COVID-19 vaccination status (question number 25–37). A detailed breakdown of the questions according to the KAP model is described in .

The study tool for PW included 42 questions divided into three sections. The first 11 questions gathered details regarding the current pregnancy status, health history and antenatal care visits. The second section (questions 12–36) included questions on the knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding influenza and influenza vaccine in pregnancy. The third section (questions 37–42) asked about demographic details such as age, education, marital status, and employment status. A detailed breakdown of the questions according to the KAP model is described in .

The response options could be ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘don’t know’ or a set of alternatives/possible answers. Both PW and HCWs were given 12 statements which assessed attitudes toward the influenza vaccine using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. For each component, higher values corresponded to more positive beliefs and attitudes toward the vaccine and higher levels of knowledge. The English language questionnaire was first translated into regional languages (Urdu and Pashto) and a backward translation was done to ensure consistency. The translated tools were pretested in a small sample. The questionnaire took 15–20 minutes to complete and was administered by trained community health workers (CHWs)/data collectors at all study sites using an online app built with the REDCap software. Data was then transferred daily and stored at a local server at the Aga Khan University Hospital with restricted access.

Sample size

Sample size was calculated using the standard formula for cross-sectional studies:

where: n = estimated sample size, Zα at 5% level of significance = 1.96, d = level of precision, estimated to be 0.05, p = We assumed an adequate knowledge level of 50% among HCWs for maximum sample size; hence, the primary sample size = ((1.96)2 × (0.5 × 0.5))/(0.05 × 0.05) = 384 subjects. The expected response rate was estimated to be 90%. Therefore, the planned sample size = 384 × 100/90 = 426 subjects. For healthcare workers, the calculation was done at the national level in Pakistan. Regarding pregnant women, the sample size was determined for the province of Sindh and extended to encompass other provinces as well.

Statistical analysis

Mean ± SD were reported for continuous variables, median (IQR) were reported for non-normal discrete variables and numbers with percentages were reported for categorical variables. Scores for knowledge and practice questions were coded as: 0 = “No,” 1 = “Yes” and 2 = “Don’t know.” To calculate the score, a correct answer was computed as one, and a wrong answer was computed as 0. Not answering or not knowing was considered neutral and calculated as zero. Attitude scores were obtained by adding Likert scale points for each question, values ranged from ‘strongly agree’ = 5 to ‘strongly disagree’ = 1. A simple linear regression model was used to predict the knowledge, attitude and practice scores at univariate level using socio-demographic characteristics, all the factors with p-value <.10 were considered for multivariate analysis. A backward selection procedure was used to derive a parsimonious model for retaining only variables significant at p-value ≤.05.Citation14 We assessed multicollinearity among independent variables using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) at a cutoff point of 10.0. All analyses were performed using STATA version 17.0.

Quality assurance

To ensure the study’s credibility, we implemented quality control measures at various stages, starting with selecting and training interviewers. The interviewers were chosen based on specific criteria, such as having at least a secondary level of education, proficiency in one of the major local languages, and prior experience administering electronic app-based surveys. We conducted a one-day training process for interviewers, including a simulation exercise using a lay respondent to replicate the entire survey process. During the initial visits and interviews, a trained team member or field supervisor was present to supervise and ensure proper implementation of the consent process and adherence to the established protocols. We performed pilot testing on 5% of the sample size. As part of our routine quality checks (QC), approximately 10% of the interviews were selected for verification through phone calls.

Qualitative component

Participants and data collection

We adopted a qualitative study design, with includes in-depth interviews and focused group discussions with healthcare workers in Pakistan. The in-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted with healthcare workers (HCWs) at various stakeholder positions. Participants were selected through purposive sampling. The interviews were conducted either in-person or online until a point of saturation was reached. In addition, three separate focus group discussions (FGDs) were held with 10–12 HCWs each, including community physicians at Rehri Goth and residents and nurses at the Aga Khan University Hospital. To ensure a diversity of perspectives, we made sure that at least half of our interviewees were women, participants were both vaccinated and unvaccinated, and had a range of ages and occupations.

We developed a semi-structured questionnaire in Urdu based on literature and expert consultation. The topics covered in the questionnaire included perceptions about influenza as a disease, vaccine effectiveness and safety, barriers to vaccine uptake, and thoughts on vaccine promotion strategies. Prior to the study’s commencement, two pilot interviews were conducted to test the semi-structured questionnaire and refine the flow of the interview.

HK, a research coordinator with a master’s level qualitative research training, conducted the IDIs and FGDs from September till December 2021. The interviews lasted an average of 45–60 minutes and were conducted in a separate area using open-ended questions and probes. The responses were recorded with a portable recorder without disclosing participants’ identification, and field notes were taken to contextualize the findings. No repeat interviews were conducted.

Data were collected on socio-demographics, knowledge regarding the influenza vaccine, attitudes, and beliefs toward vaccine utilization. The anonymized audio recordings, transcripts, and notes were stored on password-protected institutional servers accessible only to investigators at AKU. Finally, participant quotations were identified by a unique number.

Content analysis

The data collected through semi-structured interviews was analyzed through inductive thematic analysis. The interviews were translated from Urdu to English and verbatim transcription of the interviews was done. The data was manually coded into themes, ensuring consistency before and after translation. Relevant themes that emerged from codes, were independently identified by HK and SS through an iterative process. The transcripts were coded using colored pens with each code assigned a different color and written in the margins of the transcript next to the relevant text. A matrix was used to organize the data by codes and participants, enabling comparison of the frequency and distribution of codes across different participants. The codes were then organized into categories based on their relevance to the research question. The final set of codes included seven categories, which were organized into three broad themes: knowledge of influenza disease and vaccine, HCWs’ perceptions of motivators and barriers to influenza vaccination uptake, and HCW’s attitudes toward vaccine promotion. MIN reviewed the themes and resolved discrepancies between investigators. Reporting adheres to the COREQ criteria.Citation15

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from Aga Khan University’s Ethical Review Committee (ERC 2021–6649–18992). No personal identifiers were collected. Interviews were conducted after obtaining consent and taking care of confidentiality of the participants.

Results

Quantitative results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the HCWs

describes the sociodemographic characteristics and COVID-19 vaccination status of the 420 HCWs enrolled in the study. There was an almost equal representation of participants from all provinces. The mean age was 33.7 ± 7.8 years. Majority of the HCWs (52.6%) were males, 49.8% were doctors and 34.8% were employed in the medicine department. COVID-19 vaccination rates were high (96.4%) in the cohort.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the enrolled healthcare workers.

Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of healthcare workers regarding influenza vaccine

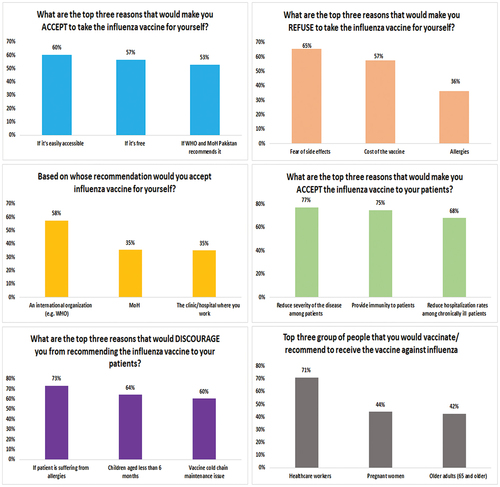

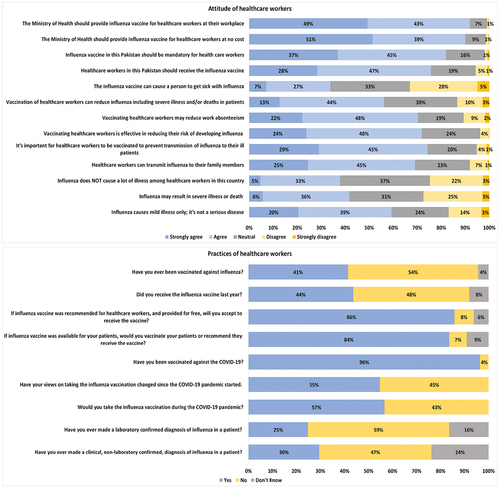

describes the influenza-related knowledge of the healthcare workers. Of the 420 HCWs enrolled, 39% believed that influenza causes mild illness only; it’s not a serious disease. Only 25% of the HCWs ever made a laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of influenza in their practice. The most common reasons for vaccine refusal were, fear of side effects (65%), cost of the vaccine (57%) and allergies (36%). They identified HCWs (71%), pregnant women (44%), and older adults (65 years and above) (42%) as the priority groups to receive the vaccine. Majority of the HCWs believed that the vaccine reduced disease severity (77%), provided immunity (75%) and reduced hospitalization in high-risk groups (68%). describes the attitudes and practices of the HCWs. Only 44% of the HCWs were vaccinated, however, their intent to receive the vaccine was high (86%) and a similar proportion were willing to recommend the vaccine to their patients. More than half of the HCWs (58%) were willing to receive the flu vaccine if an international organization (such as the WHO) recommended it.

Sociodemographic predictors of KAP scores among HCWs

and S1 describe the simple linear regression analysis of sociodemographic variables on KAP scores. Among healthcare workers, residing in KPK (β: −3.9, P = .002) and Baluchistan province (β: −13.7 P < .001), being employed as a nurse as compared to a doctor (β: −6.2, P < .001), having a work experience of 5–9 years as compared to <5 years (β: −2.25, P = .04) were predictors for a poor attitude toward vaccine uptake. Residing in Baluchistan province (β: −1.6, P < .001) and being employed as a nurse (β: −0.56, P = .029) were associated with poor practice scores. HCWs residing in Islamabad (β: 2.3, P < .001), female HCWs (β: 0.43, P = .045), and those vaccinated against COVID-19 (β: 2.2, P < .001) had a greater probability for higher practice scores.

Table 2. Sociodemographic predictors of KAP scores among healthcare workers.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the pregnant women

describes the sociodemographic characteristics of the pregnant women. Most respondents (56.7%) were residents of Sindh province, 34.0% were aged between 25–29 years, 39.6% received no formal education and only 6% were employed. Mean gestational age at the time of interview was 25.5 ± 12.8 weeks. The median number of total pregnancies was three (IQR 2–5). Only, 27.9% of the PW had received the COVID-19 vaccine.

Table 3. Sociodemographic characteristics of the enrolled pregnant women.

Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of pregnant women regarding influenza vaccine

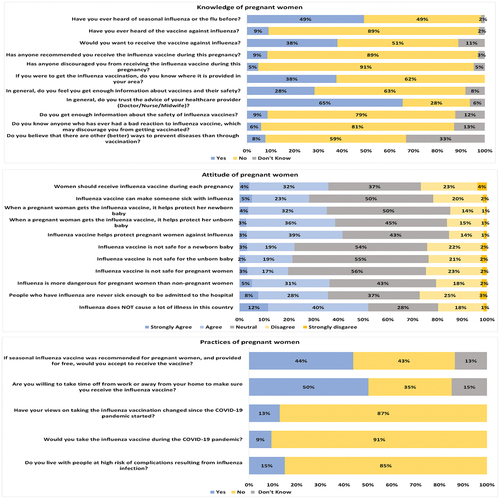

describes the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the pregnant women. Overall, 9% of the PW had heard of the vaccine previously and were recommended by HCWs to receive the vaccine during their antenatal visits, 38% of the PW wanted to receive the vaccine and knew where it would be available in their area, 5% were discouraged by their community from receiving the vaccine during pregnancy, 39% of the PW agreed/strongly agreed that the vaccine would protect their unborn baby while 20% agreed/strongly agreed with the statement that it was not safe for pregnant women. Forty-four percent of the pregnant women were willing to get the vaccine if it were recommended to them and available free of cost.

Sociodemographic predictors of KAP scores among PW

and S2 describe the simple linear regression analysis of sociodemographic variables on KAP scores among PW. As compared to pregnant women residing in urban Sindh, PW from Islamabad, KPK and Baluchistan province had lower knowledge scores as shown by negative coefficients (β: −0.80, P < .001), (β: −1.74, P < .001) and (β: −1.00, P < .001) respectively. An education level of minimum secondary school (β: 0.53, P = .014), higher secondary or above (β: 0.69, P = 0.008) and being currently employed (β: 0.73, P = .023) were significantly associated with higher knowledge scores. Belonging to the age group of less than 18 years was associated with both poor attitude scores (β: −4.25, P = .024) and poor practice scores (β: −0.77, P = .026). An education level of minimum secondary (β: 1.8, P = .021) and higher secondary or above (β: 2.2, P = .018) was a predictor of higher attitude scores whereas having received the COVID-19 vaccination was associated with a greater probability for higher practice scores (β: 0.53, P < .001).

Table 4. Sociodemographic predictors of KAP scores among pregnant women.

Qualitative results

We conducted 11 IDIs and three FGDs each with 10 participants. Only two out of the 11 IDI participants were vaccinated whereas all the FGD participants had received the flu vaccine. The characteristics of the HCWs who participated in the interviews are described in . The qualitative study highlighted three themes:

Table 5. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants in IDIs and FGDs.

Theme 1: HCWs’ knowledge of influenza and its prevention

Most HCWs did not have an appreciable knowledge of the disease and personal risk factors such as chronic illness and asthma which are associated with influenza complications. Participants were aware of the suboptimal vaccine coverage in Pakistan compared to High-Income Countries.

Most people take vaccine in the USA and UK, but in Pakistan we don’t have much increase in vaccine coverage. (IDI #2)

According to the participants, the most vulnerable groups to receive the vaccine were children aged 6 months to 15 years, the elderly population, people with comorbidities, and HCWs.

Theme 2: HCWs’ perception of motivators and barriers to influenza vaccine uptake

HCWs acknowledged the vaccine’s importance for patients’ health, disease severity and transmissibility. Professional factors, such as workload, absenteeism, and exposure risk, contributed to increased vaccine uptake. Other factors such as employer encouragement, convenient access, and free workplace vaccines also motivated HCWs to get vaccinated.

It should be mandatory for healthcare workers to get the vaccine, since taking sick leaves is difficult and work efficiency suffers. (FGD, community physicians)

Some HCWs were confident of their immunity against infection, and they reported never having experienced severe illness. Previous side-effects to influenza vaccine (feeling sick) were a key barrier. Many HCWs cited a lack of confidence in the vaccine’s effectiveness and believed that vaccination can cause exposure to the virus and result in an influenza-like illness.

It is wrongly said that vaccination prevents flu. I believe that the vaccine itself exposes and infects us with flu virus. We suffer from flu symptoms within 3–5 days after vaccination. (FGD nurses)

One HCW who was pregnant at enrollment, was unsure of the vaccine’s safety.

I am pregnant, I do not know about the vaccine, so I do not have any idea if it is safe. Should I take it or not, first I need to consult my doctor. (FGD, nurses)

HCWs identified lack of awareness, affordability, and accessibility as key barriers. Additionally, a lack of clear, consistent communication by the government, and misrepresentation of the vaccine exaggerated by various social media sources out of conspiracy and monetary gain discouraged vaccine uptake.

People are worried they may fall ill after taking vaccine… . (IDI #5)

False information on social media is a barrier; Misleading messages on vaccination are shared around by people. From a religious point of view, people don’t believe that vaccine prevents illness. They think the vaccine is a foreign conspiracy. (IDI #7)

People don’t get vaccinated because vaccine is not available at government level. (IDI #2)

Theme 3: HCWs’ attitudes toward vaccine promotion

HCWs listed several media sources which are regularly used by the general public and can be used to disseminate vaccine-related information.

Television, WhatsApp, Facebook, and other social media are commonly used in the Pakistani population. Other than that, caller tunes and mobile networks can play a part. WHO is the most responsible organization? (IDI #13)

However, they believed the most reliable communication was provided by the WHO, government health departments and healthcare providers, vaccinators working with non-governmental organizations and spiritual leaders.

Trusted sources are our healthcare providers … vaccinators partnering with NGOs. They spread approved messages of the health department or WHO; people must also use government or WHO website. (FGD, residents)

The HCWs were aware of their responsibilities in promoting vaccine uptake among the community. Most of them believed that regular public service reminders should be circulated among the general population and HCWs. Other suggestions to improve coverage were to develop a standardized surveillance system, improve vaccine affordability, vaccine promotion, and the introduction of non-injectables.

We should increase awareness, have meetings with public health consultants, practitioners, doctors and stakeholders regarding the disease. (IDI #2)

110 %, because if they are ready to use vaccine recognizing its importance, we can educate the patients. Because every person accepts their community’s health care provider’s advice and has trust in them. Stakeholders play a very wider role. (IDI #12)

Promote influenza on electronic media and newspapers. Concise communication and messages will be helpful in awareness of the population, 80% of people are unaware of this disease, and they don’t know about what influenza is especially for old age persons. (IDI #7)

Discussion

We assessed the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of influenza vaccination among two priority groups, i.e., healthcare workers and pregnant women in four cities across Pakistan. Through a mixed methods approach, we examined the barriers and enablers of vaccine uptake among HCWs and the beliefs that influenced their decision to vaccinate themselves and recommend it to the community. The influenza vaccine coverage among HCWs in Pakistan was 44%. These coverage estimates are higher than previous surveys from Pakistan, which report around 8.8–20.1% of the healthcare workers to be vaccinated and are comparable with other WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region countries.Citation13,Citation16-18 The HCWs in our study had a low level of awareness, as only 25% of them ever made a laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of influenza in their practice and 39% of the HCWs did not perceive themselves to be susceptible to severe disease. Previously, Ali et al. reported that 60% of the HCWs believed asymptomatic hospital workers cannot transmit the virus and the vaccine contains a live virus which may cause influenza.Citation17 The HCWs are often in close contact with vulnerable populations, and these misconceptions contribute to an increased risk of infection transmission. Our qualitative interviews revealed mistrust regarding vaccine effectiveness, even in the presence of scientific evidence endorsing the vaccine’s efficacy. Previous studies showed that 60.5% of the HCWs from Pakistan perceived vaccination as inadequate in providing complete protection against the flu, possibly due to inadequate coverage and a mismatch between the vaccine and the circulating viral strains.Citation16 Most HCWs in Pakistan lack awareness of the WHO Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) flu guidelines.Citation16 They require accurate and up-to-date vaccine information, along with regular training sessions on the etiology and pathogenesis of influenza and reassurance regarding vaccine safety. Therefore, joint efforts involving stakeholders, healthcare workers, and media sources can effectively implement a national education and communication strategy, enhancing awareness among healthcare workers and all vulnerable groups. HCWs highlighted international and government health authorities as reliable sources for vaccine promotion. Recommendations by the World Health Organization (WHO) or the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) could notably boost vaccine uptake.

In our study, although a majority (86%) of healthcare workers (HCWs) expressed willingness to receive the vaccine, the actual vaccine coverage remained suboptimal. This discrepancy can be attributed to the challenges of affordability and accessibility that affect the general population in LMICs. There is limited vaccine production capacity, and a disparity in vaccine supply with only, 1–4% of the global supply of seasonal influenza vaccines reaching countries in Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean, and Southeast Asia.Citation19 Pakistan lacks an influenza surveillance system, and there is limited data regarding the disease burden and cost-effectiveness of the vaccine. In addition, the vaccine demand experiences unpredictable fluctuations depending on the timing and severity of the influenza outbreaks, public attitudes toward vaccination, and vaccine availability. Pakistan also lacks the infrastructure to manage vaccine delivery. The need to identify specific target groups and a limited timeframe of 2–3 months available for vaccine administration before the flu season begins results in reduced accessibility not only for influenza vaccines but also for other essential immunizations.Citation6 The financial cost of vaccines further exacerbates the situation, the vaccine costs around 2000 Pakistani rupees which is equivalent to 6.7 US dollars. This is unaffordable in comparison to the minimum daily wage of majority of the Pakistani population leading to underutilization of seasonal influenza vaccines. Thus, efforts must be made at the ministerial level to establish an influenza strong surveillance system, introduce seasonal influenza vaccine into the national policy and program, perform routine monitoring of vaccine effectiveness as well as take measures to reduce vaccine costs and manage delivery and regulatory systems, marketing and at the country-level.

In our study, the healthcare workers exhibited a sense of collective responsibility for preventing influenza transmission within the community, and they were well aware of the high-risk groups susceptible to influenza complications. The experience of the pandemic also led 55% of the HCWs to acknowledge shifts in their perceptions of vaccine acceptance, the majority of the cohort (96.4%) were vaccinated against COVID-19. Previous literature has regarded the pandemic as a quasi-experimental event that influenced various established psychological factors affecting vaccine acceptance such as the efficacy and safety of influenza vaccines, the severity of influenza itself, and the trust in healthcare professionals and health authorities regarding vaccines.Citation20 The motivation among HCWs to receive vaccination for the sake of their patients’ well-being is a positive aspect that can be leveraged to enhance vaccination rates and overall public health outcomes. This sense of responsibility can be further reinforced through education and training initiatives that underscore the pivotal role HCWs play in accomplishing public health objectives. In our study, only 9% of the pregnant women were aware of the vaccine and were recommended by HCWs to get vaccinated during their antenatal visits. This is consistent with a previous survey from Pakistan in which none of the pregnant women were vaccinated.Citation21 Most women thought that the vaccine was unsafe for the unborn baby. However, if a seasonal vaccine was recommended to them and available free of cost, 44% intended to receive it. Thus, it was evident that pregnant women lacked knowledge, but they were strongly influenced by their healthcare providers’ recommendation. This was seen in previous study from Pakistan as well.Citation21

Our study has a few strengths and limitations. We used a mixed methods approach which allowed us to gain insight about the barriers and enablers of influenza vaccine uptake. We recruited both vaccinated and unvaccinated participants as well as HCWs from various departments, occupations, stakeholder positions and both primary and tertiary care settings which allowed us to gather different perspectives. We also collected quantitative data from a large sample size of 750 pregnant women from both hospital and community settings across Pakistan. This study was conducted at the time of waxing and waning COVID-19 waves, so it became difficult to obtain qualitative data from pregnant women in Pakistan. Another limitation was that our findings were a convenience sample of participants from four major cities in Pakistan which may not be generalizable to HCWs in rural areas. Before conducting the attitudinal portion of the analysis, we could not exclude subjects who were unaware of the influenza vaccine since it would have substantially reduced our sample size.

Conclusion

We report poor knowledge and inadequate vaccine practices among HCWs. Our findings highlight several key areas among priority groups, i.e., healthcare workers and pregnant women which can be addressed by targeted interventions to increase vaccine uptake.

Author contributions

MIN, SM, AA, WK and FJ conceptualized the study and its methodology, MIN, SK, HK, JM contributed to implementation of the research. MIN, MFQ, SS and HK contributed to the quantitative and qualitative data analysis and writing of the manuscript. All authors had access to the data, contributed to all drafts of the paper and approved the final copy for publication.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from Aga Khan University’s Ethical Review Committee (ERC 2021–6649–18992). No personal identifiers were collected. Interviews were conducted after obtaining consent and taking care of confidentiality of the participants.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (57.6 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the pregnant women and healthcare workers who participated in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.We have not uploaded the data on a repository and so there is no URL provided.

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2258627.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. Seasonal influenza factsheet. 2022.

- EMRO W. Global influenza strategy 2019 to 2030. Wkly Epidemiol Monit. 2019.

- CDC. Estimated influenza illnesses, medical visits, and hospitalizations averted by vaccination in the United States — 2019–2020 influenza season. 2020.

- Oakley S, Bouchet J, Costello P, Parker J. Influenza vaccine uptake among at-risk adults (aged 16–64 years) in the UK: a retrospective database analysis. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1734. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11736-2.

- WHO. WHO SAGE seasonal influenza vaccination recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020.

- Farrukh MJ, Ming LC, Zaidi STR, Khan TM. Barriers and strategies to improve influenza vaccination in Pakistan. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10(6):881–11. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2016.11.021.

- Kilich E, Dada S, Francis MR, Tazare J, Chico RM, Paterson P, Larson HJ. Factors that influence vaccination decision-making among pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2020;15(7):e0234827. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234827.

- Benowitz I, Esposito DB, Gracey KD, Shapiro ED, Vázquez M. Influenza vaccine given to pregnant women reduces hospitalization due to influenza in their infants. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(12):1355–61. doi:10.1086/657309.

- Collins J, Alona I, Tooher R, Marshall H. Increased awareness and health care provider endorsement is required to encourage pregnant women to be vaccinated. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(10):2922–9. doi:10.4161/21645515.2014.971606.

- Vishram B, Letley L, Jan Van Hoek A, Silverton L, Donovan H, Adams C, Green D, Edwards A, Yarwood J, Bedford H, et al. Vaccination in pregnancy: attitudes of nurses, midwives and health visitors in England. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(1):179–88. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1382789.

- Statistics PBo. Salient features of final census-2017. 2022.

- Bresee JS, Lafond KE, McCarron M, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Chu SY, Ebama M, Hinman AR, Xeuatvongsa A, Bino S, Richardson D, et al. The partnership for influenza vaccine introduction (PIVI): supporting influenza vaccine program development in low and middle-income countries through public-private partnerships. Vaccine. 2019;37(35):5089–95. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.06.049.

- Shahid S, Kalhoro S, Khwaja H, Hussainyar MA, Mehmood J, Qazi MF, Abubakar A, Mohamed S, Khan W, Jehan F, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards seasonal influenza vaccination among pregnant women and healthcare workers: a cross-sectional survey in Afghanistan. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2023;17(3):e13101. doi:10.1111/irv.13101.

- Steyerberg E. Clinical prediction models: a practical approach to development, validation, and updating. 2009.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Umbreen G, Rehman A, Avais M, Jabeen C, Sadiq S, Maqsood R, Rashid HB, Afzal S, Webby RJ, Chaudhry M, et al. Knowledge, attitude, practice and barriers associated with influenza vaccination among health care professionals working at tertiary care hospitals in Lahore, Pakistan: a multicenter analytical cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11(1):136. doi:10.3390/vaccines11010136.

- Ali I, Ijaz M, Rehman IU, Rahim A, Knowledge AH. Attitude, awareness, and barriers toward influenza vaccination among medical doctors at tertiary care health settings in Peshawar, Pakistan-a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2018;6:173. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00173.

- Zaraket H, Melhem N, Malik M, Khan WM, Dbaibo G, Abubakar A. Review of seasonal influenza vaccination in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: policies, use and barriers. J Infect Public Health. 2019;12(4):472–8. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2018.10.009.

- Palache A. Seasonal influenza vaccine provision in 157 countries (2004-2009) and the potential influence of national public health policies. Vaccine. 2011;29(51):9459–66. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.030.

- Soveri A, Karlsson LC, Antfolk J, Mäki O, Karlsson L, Karlsson H, Nolvi S, Karukivi M, Lindfelt M, Lewandowsky S, et al. Spillover effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on attitudes to influenza and childhood vaccines. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):764. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-15653-4.

- Khan AA, Varan AK, Esteves-Jaramillo A, Siddiqui M, Sultana S, Ali AS, Zaidi AKM, Omer SB. Influenza vaccine acceptance among pregnant women in urban slum areas, Karachi, Pakistan. Vaccine. 2015;33(39):5103–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.014.