ABSTRACT

Expanding access to HPV vaccination is critical to increasing HPV vaccine uptake. We assessed the determinants and barriers to consistent offering of HPV vaccine among healthcare facilities. This was a cross-sectional survey of healthcare providers (HCPs) in Texas. Prevalence of the reasons healthcare practices do not consistently offer HPV vaccination was estimated. Multivariable regression analyses were conducted. Of 1169 HCPs included in the study, 47.5% (95% CI: 44.6–50.3%) reported their practices do not provide HPV vaccination or do not offer it consistently. Compared to physicians, nurses had 77% lower odds (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR): 0.23, 95% CI: 0.16–0.32, p-value: < .001), and physician assistants had 89% lower odds (AOR: 0.11, 95% CI: 0.07–0.16, p-value: < .001) of their healthcare practices consistently offering HPV vaccination. Compared to university/teaching hospitals, the odds of healthcare practices consistently offering HPV vaccination were 44% lower (AOR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.35–0.91, p-value: 0.019) in solo practices but 266% higher (AOR: 3.66, 95% CI: 2.04–6.58, p-value: < .001) in FQHC/public facilities. The common reasons healthcare practices do not consistently offer HPV vaccination were; HPV vaccination is not within the scope of the practice (48.1%), referrals to other clinics (27.7%), and limited personnel (11.4%). Non-physicians were more likely to report that HPV vaccination was not in their scope and to refer patients than physicians. Moreover, solo practices were more likely to report challenges with acquisition and storage of the vaccine and referral of patients as reasons for not consistently offering HPV vaccination than university/teaching hospitals, FQHC/public facilities, or group practices. System-level interventions including training of non-physicians and expansion of practice enrollment in programs that support HPV vaccine acquisition and storage are needed.

Introduction

HPV infections are highly prevalent and impose an enormous economic burden on individuals and governments.Citation1,Citation2 In the United States, about 13 million new HPV infections occur annually.Citation3 These HPV infections have been linked with 80% of HPV-associated cancers, including cancer of the cervix, vagina, vulva, anus, oropharynx, and penis.Citation1 In addition to the four billion dollars in lost productivity from premature mortality, the U.S. spends eight billion dollars annually in direct medical costs to prevent and treat HPV-associated diseases.Citation2,Citation4 HPV vaccine is safe and effective in preventing HPV infections and associated diseases.Citation5–7 Therefore, all males and females are recommended to receive HPV vaccination at ages 11–12 up to 26 years, with the option of starting as early as nine years.Citation8 Adults aged 27 to 45 could get vaccinated based on a shared decision with their providers.Citation8

Despite its effectiveness, the HPV vaccination rate in the United States is behind target, with Texas having one of the lowest HPV vaccination rates nationally.Citation9–11 In 2022, the HPV vaccination completion rate (Up-To-Date) nationally in the United States was 63%, whereas, in Texas, the completion rate was only 59%.Citation9 Several patient and provider-level factors have been identified as barriers to HPV vaccination recommendation and uptake.Citation12–14 For instance, at the patient level, HPV vaccine hesitancy from misinformation on the safety of the HPV vaccine persists in the U.S., despite evidence to the contrary.Citation15,Citation16 More so, provider-level factors such as healthcare providers’ knowledge and self-efficacy in counseling hesitant patients also influence the recommendation and uptake of HPV vaccination.Citation17–20 However, health system factors, including those at the practice level, substantially impact the ability of healthcare facilities to offer HPV vaccination to eligible patients. For example, the recommendation and offering of HPV vaccination at the practice level vary by the type of healthcare facility.Citation12,Citation21 In addition, healthcare organizations with structured HPV training models for HCPs tend to have higher vaccination rates.Citation22,Citation23 More so, lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic indicate that U.S. counties with resource-constrained health systems defined by healthcare workforce, infrastructure, and spending per capita report less vaccination uptake.Citation24 Therefore, it is critical to understand how system-level factors impact the consistent offering of HPV vaccination by healthcare practices.

However, while the literature is replete with studies on patient and provider-level determinants of HPV vaccination recommendation and uptake, HPV vaccination barriers at the organizational or system level remain understudied. Moreover, amidst laudable strategies, such as the Vaccine for Children (VFC) program, which targets health system vaccination barriers in the U.S., HPV vaccination rates have continued to be suboptimal.Citation25,Citation26 Limited studies have specifically assessed why healthcare practices fail to offer HPV vaccination to eligible patients consistently. Also, there is a paucity of studies that have examined provider and practice-related factors associated with the consistent provision of HPV vaccination by healthcare practices. The consistent offering of HPV vaccination by healthcare practices may help boost HPV vaccination rates. Also, understanding how variations in the structure and systems of different healthcare facilities impact the consistent offering of HPV vaccination could inform tailored strategies to ensure healthcare facilities offer HPV vaccination to patients at every clinical encounter. This insight will be valuable in addressing systemic gaps in HPV vaccination uptake and inform future policies and interventions to expand HPV vaccination access and mitigate barriers at the practice level. We used data from frontline HCPs to determine reasons practices do not consistently offer HPV vaccination and the factors associated with the consistent offering of HPV vaccination by healthcare practices.

Methods

Study design, data source, and population

We conducted a cross-sectional study using data from a survey that targeted all healthcare providers practicing in Texas. The survey was administered between January and April 2021 by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. A list of all healthcare providers was obtained from the LexisNexis referential database.Citation27 This database contains all HCPs practicing in Texas with their e-mail addresses, a description of the provider type, and sex. The eligibility criteria were healthcare professionals, including physicians (internists, pediatricians, obstetricians/gynecologists, and family medicine physicians), nurse practitioners, and physician assistants with a current practicing license in Texas, and for whom e-mail addresses were available in the LexisNexis database. All eligible HCPs received an e-mail invitation to complete an online survey after providing informed consent. The survey was estimated to be completed in ten minutes, and all participants were compensated with a $10 gift card. The study was approved by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (IRB No: 2019–1257) and is reported following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.Citation28

Study measures

Dependent variables

Offering of HPV vaccination by healthcare practice or facility

This was measured using the survey question, “Does your practice offer HPV vaccination?” Possible responses were, “Yes, always offered,” “Yes, but not consistently,” “No,” and “I don’t know.” Consistent with the CDC ACIP guideline for HCPs to offer HPV vaccination at every clinic encounter, we combined “Yes, but not consistently” and “No” responses. Thus, this variable was operationalized as binary, “Yes, always offered” vs. “No or not consistently.” All those who responded, “I don’t know,” (n = 114) were excluded from the study.

Reasons practice does not consistently offer HPV vaccination

All HCPs who responded “Yes, but not consistently” or “No” to the preceding question were asked to select all that applied to a follow-up question, “Please indicate why your practice setting does not consistently offer HPV vaccination.” The reasons assessed were “Limited dedicated personnel,” “Challenges with vaccine acquisition,” “Challenges with vaccine storage,” “We frequently run out of vaccine due to limited stock,” “Refer to other clinics,” “HPV vaccines are controversial,” “Not in our scope,” “We choose not to,” and “Other.”

Independent variables

Healthcare practice-related factors

Practice-related factors assessed were practice location (rural vs. urban), practice type (solo practice, group practice, university or teaching hospital, Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC)/public facility, and Other), and the number of patients seen weekly (0–50, 51–100, and >100).

HCPs’ sociodemographic factors

The following sociodemographic characteristics of HCPs were assessed, HCPs’ sex (male vs. female), age (<35 years, 35–54 years, and ≥55 years), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic Other), provider type (physician, nurse, physician assistant, and other), and years in practice (≤10 years, 11–20 years, and >20 years).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented for provider and practice-related characteristics in the overall population of HCPs included in the study using frequency and proportions. Also, we described the distribution of provider and practice-related characteristics stratified by the consistent offering of HPV vaccination by healthcare practice using proportions and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The prevalence of HCPs who reported their healthcare practices always offered HPV vaccination was estimated. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine provider and practice-related factors associated with healthcare practices providing HPV vaccination consistently. We did not conduct any variable selection. Variables included in the regression model were selected a priori based on past literature and relevance to the study. In addition, the prevalence for each reason healthcare practices do not consistently offer HPV vaccination was estimated in the overall population of respondents and stratified by provider type and practice type. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p-value <.05. All analyses were conducted using Stata/IC Version 15.1.

Results

A total of 1283 HCPs completed the overall survey (response rate of 7%). Among HCPs responding to the question, does your practice offer HPV vaccination, 614 (52.5% (95% CI: 49.7–55.4%)) reported their practices always offer HPV vaccination, and 555 (47.5% (95% CI: 44.6–50.3%)) reported their practices do not provide HPV vaccination or do not offer it consistently (). Overall, HCPs were predominantly aged 35–54 years (62.0%), females (76.0%), non-Hispanic Whites (54.6%), physicians (41.5%), and practiced in urban settings (95.5%). Also, HCPs worked in group practices (34.1%), university/teaching hospitals (27.2%), FQHC/public facilities (10.1%), or other facilities (16.3%) ().

Table 1. Baseline descriptive statistics and prevalence of practices that consistently offer HPV vaccination stratified by the provider and practice-level characteristics (N = 1169).

Healthcare practices were more likely to consistently offer HPV vaccination if providers were physicians (75.9%) than nurses (42.7%) or physicians assistant (28.8%) (). Also, the prevalence of healthcare practices consistently offering HPV vaccination was higher in FQHC/public facilities (78.8%) than in group practice (60.6%), university/teaching hospitals (45.6%), or solo practice (42.4%). In addition, healthcare practices were more likely to consistently offer HPV vaccination if HCPs see 51–100 patients per week in their practice (65.4%) compared to those who see ≤ 50 patients weekly (38.0%) ().

Findings from multivariable regression analysis revealed that compared to physicians, nurses had 77% lower odds (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR): 0.23, 95% CI: 0.16–0.32, p-value: <.001) and physician assistants had 89% lower odds (AOR: 0.11, 95% CI: 0.07–0.16, p-value: <.001) of their healthcare practices consistently offering HPV vaccination (). Also, compared to university/teaching hospitals, the odds of healthcare practices consistently offering HPV vaccination were 44% lower (AOR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.35–0.91, p-value: .019) in solo practices and 266% higher (AOR: 3.66, 95% CI: 2.04–6.58, p-value: <.001) in FQHC/public facilities.

Table 2. Multivariable regression analyses of the association between provider and practice-related characteristics and the consistent offering of HPV vaccination by healthcare practices.

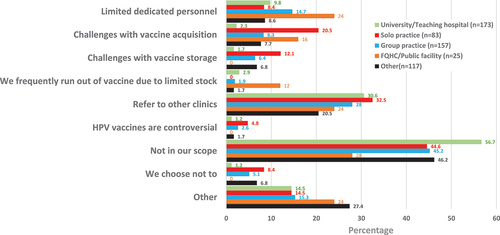

As shown in , the most common reason healthcare practice settings do not consistently offer HPV vaccination is that HPV vaccination is not within the scope of the practice (48.1% (95% CI: 43.9–52.3%)) and referrals to other clinics (27.7% (95% CI: 24.2–31.6)). Also, HCPs reported that practices do not consistently offer HPV vaccination due to limited personnel (11.4% (95% CI: 9.0–14.3)), challenges with vaccine acquisition (8.5% (95% CI: 6.4–11.1)), and challenges with vaccine storage (5.6% (95% CI: 4.0–7.8)).

Figure 1. Reasons why healthcare practices do not consistently offer HPV vaccination to eligible patients (N = 555).

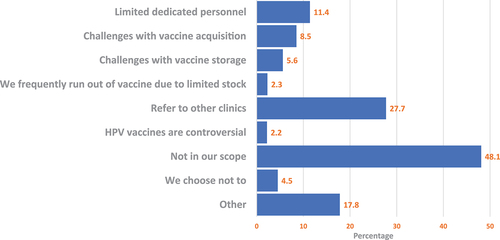

Upon stratification of the reason practice settings do not consistently offer HPV vaccination by provider type, non-physicians were more likely to report that HPV vaccination was not in their scope than physicians (52.1% vs. 33.3%) (). Also, non-physicians were more likely to refer patients for HPV vaccination than physicians (30.4% vs. 18.0%). However, physicians were more likely to report limited dedicated personnel (20.5% vs. 8.9%), challenges with vaccine acquisition (15.4% vs. 6.6%), challenges with vaccine storage (9.4% vs. 4.6%), or choose not to (6.8% vs. 3.9%) as reasons for not consistently offering HPV vaccination in their practices ().

Figure 2. Reasons why healthcare practices do not consistently offer HPV vaccination to eligible patients stratified by provider type (N = 555).

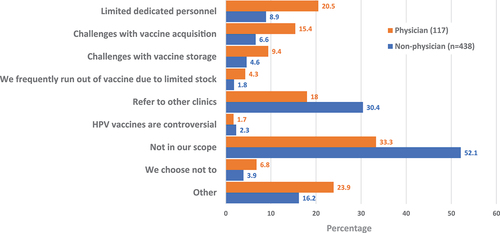

Furthermore, stratification of the reasons practices do not consistently offer HPV vaccination by practice type revealed that HCPs in university/teaching hospitals (56.7%) were more likely to report that HPV vaccination was not in their scope than those in group practices (45.2%), solo practices (44.6%), or FQHCs/public facilities (28.0%) (). Similarly, HCPs in university/teaching hospitals were more likely to report referral of patients for HPV vaccination as the reason practice settings do not consistently provide HPV vaccination than those in group practices or public facilities (30.6% vs. 28.0% vs. 24%). Also, solo practices were more likely to report challenges with the acquisition and storage of the vaccine and referral of patients as the reason for not consistently offering HPV vaccination than University/teaching hospitals, FQHC/public facilities, or group practices ().

Discussion

We aimed to understand why healthcare practices do not consistently offer HPV vaccination to eligible patients and identify the factors associated with the consistent offering of HPV vaccination by healthcare practices. We found that only about half of the healthcare practices in Texas consistently offer HPV vaccination, indicating a significant gap in adherence to the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) guideline that patients should be offered vaccines at every clinical encounter.Citation29 The low rate of consistent HPV vaccination offered by healthcare practices, as found in our study, may underscore the suboptimal HPV vaccination rates seen locally and nationally.Citation9 Findings from several studies provide overwhelming evidence to support the willingness of patients to accept the HPV vaccination if their providers offer it.Citation30–32 This calls for novel ways of expanding access to HPV vaccination by strengthening healthcare systems with resources and capabilities to offer HPV vaccination consistently. There is an urgent need to expand the distribution of HPV vaccination to non-traditional medical settings, such as pharmacies and specialty clinics, and to utilize venues outside conventional medical settings.Citation33,Citation34 Moreover, a President’s Cancer Panel earmarked expanding avenues for access to HPV vaccination services as a means to accelerate HPV vaccine uptake.Citation33 Besides pharmacies and major hospitals, schools remain a major site for dispensing HPV vaccines, particularly in states with HPV vaccination mandates.Citation35,Citation36 Therefore, recruiting the full spectrum of various health facilities to offer HPV vaccination consistently will help increase access to HPV vaccines. Moreover, since various health facilities serve distinct demography, this approach could rapidly expand HPV vaccine access within communities.

While there are known patient-level determinants of HPV vaccination recommendation, our findings highlight opportunities to identify and address practice-level barriers to HPV vaccination.Citation37,Citation38 We found that the type of healthcare provider and the type of practice were associated with offering HPV vaccination consistently. Specifically, practices were more likely to consistently offer HPV vaccination if the healthcare provider was a physician compared to a nurse or a physician assistant. The relationship between the type of healthcare provider and the provision of HPV vaccination suggests that interventions need to be tailored to provider type (i.e., physicians vs. advanced-level practitioners). Previous studies have shown that increasing healthcare providers’ knowledge of HPV correlates with their likelihood to recommend HPV vaccines to eligible populations.Citation39 Thus, healthcare practices could be well positioned to consistently offer HPV vaccination by facilitating routine HPV vaccination training for providers.Citation22,Citation40 Furthermore, Federally Qualified Health Centers and public facilities were more likely to offer HPV vaccination than university or solo practices. This suggests that organizational systems and objectives, such as a focus on preventive care and laid down policies or protocols, may influence the offering of HPV vaccination. For example, a study among physicians indicated that a substantial proportion (70%) expressed that their capacity to recommend the HPV vaccine was restricted due to the absence of preventive care visits for patients belonging to the eligible age group.Citation41 Understanding and leveraging practice uniqueness could be a promising strategy for providing targeted practice-level interventions to improve HPV vaccination recommendations.

Importantly, our study provides valuable insights into why healthcare practices do not offer HPV vaccination consistently. We found that the most common reasons healthcare practice settings do not consistently offer HPV vaccination were that it is not within the scope of their practice, referrals to other clinics, limited personnel, and logistical challenges of handling vaccines such as vaccine acquisition and storage. Also, solo practices were more likely to report challenges with vaccine acquisition and storage and referral of patients as the reason for not consistently offering HPV vaccines, which resonates with a previous study.Citation42 For solo practices, the cost associated with storing the vaccine and the logistics of maintaining vaccine stocks may not be enough incentive to offer HPV vaccination. However, the VFC program which provides a system to support practices in stocking, storing, and handling vaccines is pivotal in enhancing vaccine accessibility and delivery to patients at no cost.Citation25 Therefore, novel ways of expanding the enrollment of practices in VFC are needed to strengthen its impact and help address the reasons practices are not offering HPV vaccination consistently. More so, a national survey of private practitioners in the U.S. found significant dissatisfaction with the vaccine payment administration.Citation43 It’s also been shown that one of the significant barriers impeding the offering of HPV vaccination is the reimbursement model, which is known to affect the market access for HPV vaccines and immunotherapeutics.Citation44,Citation45 Increasing reimbursement rates and timeliness while reducing the complexities of stocking vaccines would mitigate VFC enrollment barriers and help incentivize practices to enroll in the VFC program.Citation46 Currently, assessing HPV vaccination is not one of the payment quality metrics.Citation47 This lack of emphasis on HPV vaccination in quality metrics could lead to a lower prioritization of HPV vaccination in healthcare systems. Our findings shed light on the significant role of healthcare providers and the practice settings in providing HPV vaccination and highlight the need for system-level interventions to improve HPV vaccination rates in specific provider and practice contexts.

From a policy perspective, our findings suggest that policies aimed at increasing HPV vaccination rates should consider the role of healthcare providers and practice settings. Such policies should emphasize the need to train and equip healthcare providers with the skills and resources to increase their self-efficacy to make strong recommendations.Citation40 In addition, policies could encourage or require practice settings to offer HPV vaccination consistently by expanding quality measures or incentives to include HPV vaccination. Moreover, our findings could inform the development of advocacy campaigns to increase HPV vaccination rates. These campaigns should be tailored to solo practices, nurses, and physician assistants who are less likely to consistently offer HPV vaccination and frequently refer patients to other clinics. Campaigns could provide information and resources tailored to these providers or settings and share success stories and best practices from other practices that consistently offer HPV vaccination.

Our study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, as with any cross-sectional study, we are unable to establish causality due to the simultaneous measurement of exposure and outcome. Therefore, we can only report associations and not causal relationships between the provider and practice-related factors and the offering of HPV vaccination by healthcare practices consistently. Second, our study relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to recall and social desirability biases. Providers may have overestimated or underestimated their practices’ HPV vaccination offerings, which could have influenced our results. However, we attempted to minimize this bias by assuring participants of the confidentiality of their responses. Third, most HCPs in our study practiced in urban regions, limiting the generalizability of our findings to healthcare practices in urban settings. Finally, the response rate was low. However, given that this was a study of frontline HCPs mostly in non-academic settings, the response rate is reasonable. Similar surveys involving frontline HCPs have also reported low response rates and noted challenges with recruiting HCPs for health service research.Citation48,Citation49 Also, we found no significant difference between respondents and non-respondents with regard to provider type and sex, minimizing the potential for selection bias. Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insights into the factors associated with the consistent offering of HPV vaccination by healthcare practices. Our findings underscore the importance of a systemic approach to improving HPV vaccination rates. More so, this study highlights systemic barriers to HPV vaccination and provides a foundation for future research and policy interventions to improve HPV vaccination rates. Findings from this study could inform strategies to improve HPV vaccination rates and ultimately reduce the burden of HPV-related cancers. Moreover, given that this was a state-wide survey of healthcare providers, our findings are generalizable to other states and settings with similar demographics as our study population.

In conclusion, our study highlights the need for system-level interventions to improve HPV vaccination rates. Such interventions should incorporate education and training for healthcare providers, particularly nurses and physician assistants, to increase their knowledge and self-efficacy in recommending the HPV vaccine consistently. Additionally, strategies to address the common reasons for not consistently offering HPV vaccination, such as clarifying the scope of practice and expanding practice enrollment in the VFC program, should be implemented. Future research should focus on developing and testing these interventions to improve HPV vaccination rates and ultimately reduce the burden of HPV infections and associated diseases. Our findings underscore the need for a multi-faceted approach to improving HPV vaccination rates and addressing the various reasons healthcare practices do not consistently offer HPV vaccination.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and design of the study: IO, OGC-A, SS; Formal Analyses: IO; Writing-original draft: IO, BAAK; Writing-review & editing: OGC-A, SS; Interpreted study data: IO, OGC-A, BAAK, SS; Funding acquisition: SS; Supervision: SS

Role of the funder

The funders were not involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation of data, or manuscript writing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Texas healthcare professionals for participating in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data related to this manuscript can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancers associated with human papillomavirus, United States—2015–2019. USCS data brief, no 32. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services Web site; Updated 2022 [accessed 2023 Jun]. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/about/data-briefs/no31-hpv-assoc-cancers-UnitedStates-2015-2019.htm.

- Priyadarshini M, Prabhu VS, Snedecor SJ, Corman S, Kuter BJ, Nwankwo C, Chirovsky D, Myers E. Economic value of lost productivity attributable to human papillomavirus cancer mortality in the United States. Front Public Health. 2021;8:624092. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.624092.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus: HPV infection. CDC website web site; Updated 2023. [accessed 2023 Jun]. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/about-hpv.html.

- Chesson HW, Ekwueme DU, Saraiya M, Watson M, Lowy DR, Markowitz LE. Estimates of the annual direct medical costs of the prevention and treatment of disease associated with human papillomavirus in the United States. Vaccine. 2012;30(42):6016–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.056.

- Arana JE, Harrington T, Cano M, Lewis P, Mba-Jonas A, Rongxia L, Stewart B, Markowitz LE, Shimabukuro TT. Post-licensure safety monitoring of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in the vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS), 2009–2015. Vaccine. 2018;36(13):1781–8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.034.

- Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen O, Bouchard C, Mao C, Mehlsen J, Moreira ED, Ngan Y, Petersen LK, Lazcano-Ponce E, et al. A 9-valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):711–23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1405044.

- Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, Moreira ED, Penny ME, Aranda C, Vardas E, Moi H, Jessen H, Hillman R et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV infection and disease in males. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):401–11. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0909537.

- Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, Unger ER, Romero JR, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):698–702. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a3.

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, MarkowitzLE Valier MR, Fredua B, Crowe SJ, DeSistoCL, Stokley S, James A. Singleton et al. Vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — national immunization survey–teen, United States, 2022. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(34):912–9. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7234a3.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. HPV immunization. healthy people 2030. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Updated n.d. [accessed 2021 Nov 29]. https://health.gov/healthypeople/search?query=HPV+immunization.

- Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Talluri R, Wonodi C, Shete S. Trends in HPV vaccination initiation and completion within ages 9-12 years: 2008-2018. Pediatrics (Evanston). 2021;147(6):1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-012765.

- Osaghae I, Darkoh C, Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Chan W, Wermuth P, Pande M, Cunningham SA, Shete S. Association of provider HPV vaccination training with provider assessment of HPV vaccination status and recommendation of HPV vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(6):2132755. doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2132755.

- Bynum SA, Staras SAS, Malo TL, Giuliano AR, Shenkman E, Vadaparampil ST. Factors associated with Medicaid providers’ recommendation of the HPV vaccine to low-income adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(2):190–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.006.

- Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;168(1):76–82. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2752.

- Sonawane K, Lin Y, Damgacioglu H, Zhu Y, Fernandez ME, Montealegre JR, Cazaban CG, Li R, Lairson DR, Lin Y et al. Trends in human papillomavirus vaccine safety concerns and adverse event reporting in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2124502. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24502.

- Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Talluri R, Shete SS, Shete S. Safety concerns or adverse effects as the main reason for human papillomavirus vaccine refusal: national immunization survey–teen, 2008 to 2019. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(10):1074–6. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1585.

- Vu M, King AR, Jang HM, Bednarczyk RA. Practice-, provider- and patient-level facilitators of and barriers to HPV vaccine promotion and uptake in Georgia: a qualitative study of healthcare providers’ perspectives. Health Educ Res. 2020;35(6):512–23. doi: 10.1093/her/cyaa026.

- Osaghae I, Darkoh C, Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Chan W, Wermuth PP, Pande M, Cunningham SA, Shete S. Healthcare provider’s perceived self-efficacy in HPV vaccination hesitancy counseling and HPV vaccination acceptance. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11(2):300. doi:10.3390/vaccines11020300.

- McRee A, Gilkey MB, Dempsey AF. HPV vaccine hesitancy: findings from a statewide survey of health care providers. J Pediatr Health Car. 2014;28(6):541–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.05.003.

- Rutten LJF, St. Sauver JL, Beebe TJ, Wilson PM, Jacobson DJ, Fan C, Breitkopf CR, Vadaparampil ST, Jacobson RM. Clinician knowledge, clinician barriers, and perceived parental barriers regarding human papillomavirus vaccination: association with initiation and completion rates. Vaccine. 2016;35(1):164–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.012.

- Newcomer SR, Freeman RE, Albers AN, Murgel S, Thaker J, Rechlin A, Wehner BK. Missed opportunities for human papillomavirus vaccine series initiation in a large, rural U.S. state. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(1):2016304. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2016304.

- Brewer NT, Mitchell CG, Alton Dailey S, Hora L, Fisher-Borne M, Tichy K, McCoy T. HPV vaccine communication training in healthcare systems: evaluating a train-the-trainer model. Vaccine. 2021;39(28):3731–6. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.038.

- Rand CM, Schaffer SJ, Dhepyasuwan N, Blumkin A, Albertin C, Serwint JR, Darden PM, Humiston SG, Mann KJ, Stratbucker W, et al. Provider communication, prompts, and feedback to improve HPV vaccination rates in resident clinics. Pediatrics (Evanston). 2018;141(4):e20170498. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-0498.

- Cuadros DF, Gutierrez JD, Moreno CM, Escobar S, Miller FD, Musuka G, Omori R, Coule P, MacKinnon NJ. Impact of healthcare capacity disparities on the COVID-19 vaccination coverage in the United States: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023;18:100409. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2022.100409.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines for children program (VFC). CDC web site; Updated 2022 [accessed 2023 Mar 21]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/index.html.

- Liao C, Francoeur AA, Kapp DS, Caesar MAP, Huh WK, Chan JK. Trends in human papillomavirus–associated cancers, demographic characteristics, and vaccinations in the US, 2001–2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e222530. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.2530.

- LexisNexis. Master provider referential database; Updated 2021. https://risk.lexisnexis.com/.

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;370(9596):1453–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Standards for adult immunization practice. CDC web site; Updated 2016 [accessed 2021 Nov 29]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/adults/for-practice/standards/index.html.

- Oh NL, Biddell CB, Rhodes BE, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccine uptake: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Prev Med. 2021;148:106554. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106554.

- Vu M, Berg CJ, Escoffery C, Jang HM, Nguyen TT, Travis L, Bednarczyk RA. A systematic review of practice-, provider-, and patient-level determinants impacting Asian-Americans’ human papillomavirus vaccine intention and uptake. Vaccine. 2020;38(41):6388–401. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.07.059.

- Ejezie CL, Osaghae I, Ayieko S, Cuccaro P. Adherence to the recommended HPV vaccine dosing schedule among adolescents aged 13 to 17 years: findings from the national immunization survey-teen, 2019–2020. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(4):577. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10040577.

- Overcoming barriers to low HPV vaccine uptake in the United States: recommendations from the national vaccine advisory committee. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(1):17–25. doi:10.1177/003335491613100106.

- Shah PD, Gilkey MB, Pepper JK, Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT. Promising alternative settings for HPV vaccination of US adolescents. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(2):235–46. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2013.871204.

- Carney PA, Bumatay S, Kuo GM, Darden PM, Hamilton A, Fagnan LJ, Hatch B. The interface between U.S. primary care clinics and pharmacies for HPV vaccination delivery: a scoping literature review. Prev Med Rep. 2022;28:101893. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101893.

- Stubbs B, Panozzo C, Moss J, Reiter P, Whitesell D, Brewer N. Evaluation of an intervention providing HPV vaccine in schools. Am J Hlth Behav. 2014;38(1):92–102. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.1.10.

- Mohammed KA, Geneus CJ, Osazuwa-Peters N, Adjei Boakye MPH, E TB, Burroughs TE. Disparities in provider recommendation of human papillomavirus vaccination for U.S. adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(5):592–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.005.

- Burdette AM, Webb NS, Hill TD, Jokinen-Gordon H. Race-specific trends in HPV vaccinations and provider recommendations: persistent disparities or social progress? Public Health (London). 2017;142:167–76. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2016.07.009.

- Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: the impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine. 2016;34(9):1187–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.023.

- Osaghae I, Darkoh C, Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Chan W, Wermuth PP, Pande M, Cunningham SA, Shete S. HPV vaccination training of healthcare providers and perceived self-efficacy in HPV vaccine-hesitancy counseling. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(12):2025. doi:10.3390/vaccines10122025.

- Bruno DM, Wilson TE, Gany F, Aragones A. Identifying human papillomavirus vaccination practices among primary care providers of minority, low-income and immigrant patient populations. Vaccine. 2014;32(33):4149–54. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.05.058.

- Campos-Outcalt D, Jeffcott-Pera M, Carter-Smith P, Schoof BK, Young HF. Vaccines provided by family physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(6):507–10. doi:10.1370/afm.1185.

- O’Leary ST, Allison MA, Kempe A, LindleyMC, Crane LA, Hurley LP, Brtnikova M, Beaty BL, Babbel CI, Jimenez-Zambrano A, Berman S. Vaccine financing from the perspective of primary care physicians. Pediatrics (Evanston). 2014;133(3):367–74. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2637.

- Oyedeji O, Maples JM, Gregory S, Chamberlin SM, Gatwood JD, Wilson AQ, Zite NB, Kilgore LC. Pharmacists’ perceived barriers to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination: a systematic literature review. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(11):1360. doi:10.3390/vaccines9111360.

- Jönsson B, Wilking N. Cancer vaccines and immunotherapeutics. Hum Vaccin Immunother. Guest Editors: Michael G. Hanna Alex Kudrin. 2012;8(9):1360–3. doi:10.4161/hv.21921.

- Malo TL, Hassani D, Staras SAS, Shenkman EA, Giuliano AR, Vadaparampil ST. Do Florida Medicaid providers’ barriers to HPV vaccination vary based on VFC program participation? Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(4):609–15. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1036-5.

- Grabert BK, Heisler-MacKinnon J, Liu A, Margolis MA, Cox ED, Gilkey MB. Prioritizing and implementing HPV vaccination quality improvement programs in healthcare systems: the perspective of quality improvement leaders. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(10):3577–86. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1913965.

- Asch S, Connor SE, Hamilton EG, Fox SA. Problems in recruiting community‐based physicians for health services research. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(8):591–9. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02329.x.

- Cook DA, Wittich CM, Daniels WL, West CP, Harris AM, Beebe TJ. Incentive and reminder strategies to improve response rate for internet-based physician surveys: a randomized experiment. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(9):e244. doi:10.2196/jmir.6318.