?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Teachers played an important role on the transmission of influenza in schools and communities. The study aims to investigate the influenza vaccination coverage and the factors determining flu vaccination acceptance among teachers in Hangzhou, China. A total of 1039 junior high school teachers in Hangzhou were recruited. The self-made questionnaire was used to investigate the influenza vaccine coverage among teachers and the influencing factors of influenza vaccination acceptance. Univariate analysis using the chi-square test and multivariable analysis using binary logistic regression were conducted to determine the relative predictors. The Influenza vaccine coverage among teachers was 5.9% (62/1039). 52.9% of teachers had the intention to receive influenza vaccine, 25.3% (247/977)/21.8% (213/977) of participants was hesitant/did not have the intention to get influenza vaccine. The top three sources for teachers to gain knowledge about influenza were website (72%), TV/radio (66.1%) and social media (58%). Whether get influenza vaccination before, knowledge about influenza and influenza vaccine, the beliefs for the likelihood of catching flu, the severity of getting flu, the effectiveness of influenza vaccine, the possibility of side effects after vaccination, and the troublesome of vaccination, doctors’ recommendation, as well as the situation of vaccination among other teachers were the associated factors of influenza vaccination acceptance. The influenza vaccination coverage was low but the intentions were relatively high among junior high school teachers. Future research should focus on the relationship between vaccination acceptance and behavior to increase influenza vaccination rates.

Introduction

Influenza is an acute viral respiratory infection that had a high morbidity and fatality rate throughout the world.Citation1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, there are between 290,000 and 650,000 influenza-related respiratory deaths each year, with an estimated one billion cases of influenza, of which three to five million are severe.Citation2

The most effective way to prevent influenza is influenza vaccination. According to a Cochrane analysis, influenza vaccination decreased influenza rates in healthy persons between the ages of 16 and 65 from 2.3% to 0.9%. Additionally, vaccination decreased the frequency of influenza-like illness from 21.5% to 18.1%.Citation3 For those 6 months and older, the World Health Organization and countries throughout the world recommend an annual influenza vaccination using any licensed, age-appropriate influenza vaccine,Citation4–6 especially crucial for those at high risk of influenza complications, as well as for those who live with or provide care for them, such as children aged between 6 months to 5 years, elderly individuals (aged more than 65 years), individuals with chronic medical conditions, health-care workers (HCWs), et al. Teachers are also a priority group for flu vaccination. First, schools could become centers for influenza outbreaks due to their large populations and high rates of close social contact. Each year, China reported more than 90% of the influenza epidemics that occurred in schools and childcare facilities.Citation6 Therefore, teachers work in a setting that was conducive to the transmission of disease and are highly susceptible to the influenza virus. Second, teachers infect with the flu could lead to increased absenteeism. The situation was particularly serious in countries with scarce teacher resources. There were reports showed that nearly half of schools in the Netherlands had a shortage of teachers because of the flu.Citation7 Third, teachers vaccinated against influenza could also prevent them from spreading the influenza virus to their students. School-age children are crucial in halting the spread of influenza in schools, families, and communities.Citation8–10 School absences, parental absences from work, and subsequent influenza virus infections in families could all be impacted by illness among schoolchildren during influenza season.Citation11 Last but not the least, previous studies had reportedCitation12,Citation13 that teacher’s vaccination can also increase the willingness and vaccination rate of students for influenza vaccination. Currently, In many countries, such as China,Citation6 Greece,Citation14 Poland, EU/EEA Member States (Lichtenstein, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovenia),Citation12 et al., teachers were included in the priority vaccination groups for influenza.

While there is a great need for teachers to be vaccinated, there were very few studies of teachers’ willingness to receive influenza vaccination worldwide, and from these studies, teacher vaccination rates varied widely. Studies in Poland shown that, 4.5% of teachers from primary schools reported receiving influenza vaccination.Citation12 In Czech Republic, 6% of university teachers were vaccinated against influenza.Citation13 However, In America, 58% of school employees reported receiving the 2012–2013 influenza vaccine.Citation15 In China, as far as we know, there had been no studies that had assessed the teacher’s influenza vaccine coverage rate.

The Health Belief Model (HBM) is a social cognitive model of health that makes an effort to predict and explain why people change or maintain particular health behaviors.Citation16 It was developed by social psychologists at the U.S. Public Health Service in the 1950s.Citation17 HBM has been extensively used in relation to vaccination, particularly in relation to influenza vaccination.Citation18 The HBM includes a number of key components, including perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy to engage in a behavior and cues to action. In the context of influenza, perceived susceptibility refers to one’s subjective perception of the risk of contracting influenza, while perceived severity refers to sentiments about the seriousness of contracting influenza, including evaluations of both medical/clinical consequences and possible social consequences. Perceived benefits refer to one’s perception of the benefits of getting influenza vaccination, and perceived barriers are the unfavorable features of vaccination that a person perceives as being associated with it, such as costs, physical pain, psychological concerns, or logistical access issues. Self-efficacy is the belief that one can successfully carry out the steps necessary to obtain vaccination. It is only useful to the extent that one feels this way. Cues to action might be internal (symptom, etc.) or external (a doctor’s recommendation, etc.) incentives that encourage vaccination.Citation19 Therefore, The HBM model could be used to effectively study the influencing factors of teachers’ influenza vaccination intention.

In late December 2022, China adjusted COVID-19 prevention and control measures, managing COVID-19 with measures against Class B infectious disease. That meant authorities dropped quarantine measures against people infected with COVID-19 and stopped identifying close contacts or designating high-risk and low-risk areas.Citation20 Schools re-opened and students returned to classes from online learning. At this point, it is anticipated that both influenza and SARS-CoV-2 will spread more widely, and severe cases due to co-infections might also increase. Considering the risk of infection and the consequences for teachers at school, there is a need to increase the teachers’ influenza vaccination rate.

This is, as far as we know, the first investigation of influenza vaccination among Chinese teachers. The present study aimed to (1) investigate the teachers’ influenza vaccination coverage in Hangzhou, China (2) investigate teachers’ willingness to receive influenza vaccine (3) explore the influencing factors of influenza vaccination acceptance among teachers, so as to provide policy basis for authorities during the simultaneous epidemics of influenza and COVID-19, and to increase the influenza vaccination rate of teachers against influenza.

Materials and methods

Study participants and survey design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey among junior high school teachers in Hangzhou, China, from 11 November to 12 December 2021. In order to calculate the sample size of this study, we refer to previous literatures,Citation21 and with a margin of error of 6% and an 80% power, we assumed that 40% of teachers would have an intention to be vaccinated against influenza. Using the formular below:

where Zα = 1.96, P was the influenza vaccination acceptance rate of teachers, was 0.1 × P, and taking into account 23 variables to be included in the multivariable analysis, the target sample size was 513. We used stratified random sampling method to select survey objects. The districts in Hangzhou were divided into three levels: urban, suburban, and rural. Two districts were randomly selected from each level, and two junior high schools were randomly selected in each district. At least 43 teachers were selected for each school according to the sample size. We conducted the survey on the Wen Juan Xing online platform. The QR code was generated automatically after the questionnaire was entered into the platform. Then we distributed the QR code to each survey responder via WeChat, one of mainland China’s most important and frequently used social platforms, to avoid face-to-face interaction. The participants used their smartphones to scan the QR code and complete the self-administered survey online. Finally, A total of 1039 teachers were recruited. Before completing the questionnaires, all participants were asked to consent to their participation and given the assurance that their data would be handled confidentially and de-identified.

Assessments tools

A self-administered questionnaire was designed to collect data on 1) sociodemographic characteristics, 2) the channels of obtaining information on influenza and influenza vaccine, 3) knowledge on influenza and influenza vaccine, 4) uptake of influenza vaccines, and the intention to receive influenza vaccine during this influenza season, and 5) health beliefs related with influenza infection and vaccination.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics included gender (male/female), age, working years, living place (urban, suburb, rural), teacher in charge of a class (yes/no), received influenza vaccine before (yes/no).

The channels of obtaining information on influenza and influenza vaccine

With regards to the preferred channels of obtaining information on influenza and influenza vaccine for the teachers, multiple response items (questions with multiple possible answers) were utilized. The channels included 1) books/magazines, 2) TV/radio, 3) website, such as Baidu, Google, etc., 4) social media, such as WeChat, Weibo (equivalent to Twitter), Douyin (equivalent to TikTok), etc., 5) professional HCWs, 6) family/friends/other people around. According to the channels chosen above, participants needed to choose the top one using most frequently. The top channels were divided into three categories: traditional media (books/magazines, TV/radio), new media (website, social media), and interpersonal communication (professional HCWs, family/friends/other people around).

Knowledge on influenza infection and influenza vaccine

Knowledge was evaluated using six influenza statements that queried participants about general cognition, etiological factor, routes of transmission, symptoms/complications, and influenza vaccination. There were three options: yes/no/not sure. If the participants selected the right response for each question, they received a score. Incorrect or “not sure” received no score. The overall knowledge score for influenza and influenza vaccination was determined by adding the scores for the six items. This score varied from 0 to 6. The higher the score, the more participants learned. Three categories were created from the total knowledge score: a score of 0–3 indicated being lack of knowledge, a score of 4–5 indicated being the average level of knowledge, and a score of 6 indicated having sufficient knowledge.

Uptake of influenza vaccines, and the intention to receive influenza vaccine

These was measured using a two-stage question: 1) Have you received your flu vaccine this year? Yes/No. 2) If No, are you willing to receive an influenza vaccine this year? Yes/No/Not Sure. According to the question, the participants were divided into two group. One is acceptance group, including those who had received or were willing to receive influenza vaccine this year. The other is Hesitant group, including those who were hesitant or refuse to vaccinate.

Health beliefs

The Health Belief Model (HBM) was used as the theoretical framework to measure the participants’ beliefs on influenza vaccination. The five aspects of the HBM in this study were perceived susceptibility (2 items), perceived severity (3 items), perceived benefits (2 items), perceived barriers (5 items), and cues to action (3 items). Self-efficacy was not evaluated in this study since, among the HBM constructs, it is not required to comprehend basic health behavior.Citation22,Citation23 A 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree) was used to assess the level of belief.

Data quality control

This study used a self-administered questionnaire to collect data. The questionnaire was reviewed and modified by professional experts. A pretest of about 20 people was conducted before the study was implemented, and the final version of the questionnaire was formed according to the pretest survey suggestion. The internal consistency Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient for the questionnaire was 0.718. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index was 0.758 and the p-value of Bartlett spherical test was < .05, indicating good reliability and validity of this questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

For the categorical variables, frequencies and percentages were presented. Continuous variables were summarized using median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables using numbers and proportions. Comparisons of sociodemographic, the channels of obtaining information on influenza and influenza vaccine, the different tertiles of knowledge and HBM variables of participants were analyzed between acceptance group and hesitant group. To determine the relative predictors of vaccination, a multivariable analysis using binary logistic regression was carried out. To identify the significant independent predictors of acceptance to influenza vaccination among teachers, Backward stepwise (likelihood ratio) logistic regression analysis was applied.Citation24 All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

In total, 1039 respondents accepted to participate in the study and completed the questionnaire between December 7 and December 12, 2022.

The characteristics of participants are shown in . The proportion of female (59.3%) was slightly larger than that of men (40.7%), and participants in the study who were between the ages of 41 and 50 were more prevalent (43.4%). The majority was living in rural area (64.5%). A higher proportion of participants working for 21–30 years (38.9%) responded to our survey. Most of participants were not the teachers in charge of a class (71.4%) and most of them had not been vaccinated against influenza before (76.8%).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and knowledge of teachers with different influenza vaccination intentions (N = 1039).

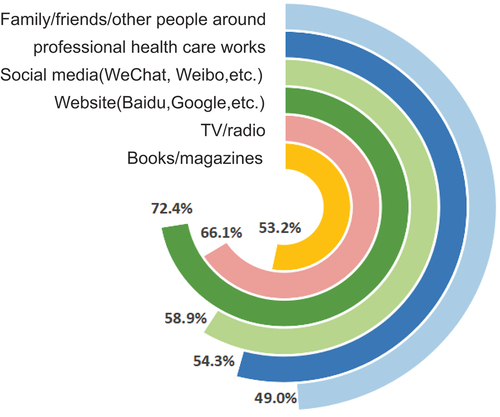

shows the proportion of different knowledge obtaining channels among teachers. Website was the most used channel, accounting for 72% of all teachers, followed by TV/radio at 66.1%. 58% of teachers used social media to get knowledge, and the figures for professional HCWs, books/magazines and people around were 54.3%, 53.2% and 49.0%, respectively. As shown in , more than half of the participants (52.8%) obtained their influenza vaccine information through new media, 27.7% through interpersonal communication, and 19.4% through traditional media. There was no statistical difference in the channel of obtaining information between teachers in two groups.

In terms of influenza and influenza vaccine knowledge, majority of participants answered questions 1, 3, and 4 correctly, with an accuracy of 93.8%, 86.5% and 81.5%, respectively. More than half of the participants answered questions 5 and 6 correctly, with an accuracy of 59.1% and 66.0%, respectively. The second question had the fewest correct answers, with only 38.8% correct. See .

Table 2. Distribution of correct answers to knowledge questions.

The median (IQR) knowledge score of the participants was 4.0 (3–5). According to the classification criteria mentioned above, participants who were lack of, average and adequate of knowledge were 57.8%, 25.5% and 16.6%, respectively. The difference in the number of individuals with varying levels of knowledge was statistically significant when compared to participants in two groups (p < .001) (see ).

In this survey, 5.9% of teachers vaccinated against influenza (62/1039). Excluding participants who had been vaccinated, more than half of participants (52.9%, 517/977) had the intention to receive influenza vaccine, 21.8% (213/977) of participants was hesitant to receive influenza vaccine, and 25.3% (247/977) of participants did not intend to get the influenza vaccination. In urban area, the participants who were willing, hesitant and unwilling to receive influenza vaccine were 60.1% (98/163), 20.2% (33/163) and 19.6% (32/163) respectively. In suburban area, the percentage were 52.1% (97/186), 20.9% (39/186) and 26.8% (50/186) respectively. In rural area, the percentage were 51.2% (322/628), 22.4% (141/628) and 26.2% (165/628), respectively.

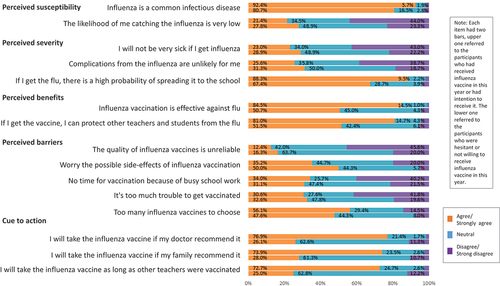

As shown in , for each item in HBM model, the proportion of different attitude (Strongly agree/agree, neutral, disagree/strongly disagree) in two groups were different, and the differences in each item were all statistically significant (p < .001).

For unvariable analysis, shows that previous influenza vaccination (p < .001) is an influencing factor for acceptance or hesitance to get influenza vaccination. Acceptance or hesitance to get influenza vaccination were statistically significant among different level of influenza and influenza vaccination knowledge (p < .001). shows that all the items of HBM models had the significant difference between acceptance or hesitance group participants (p < .001).

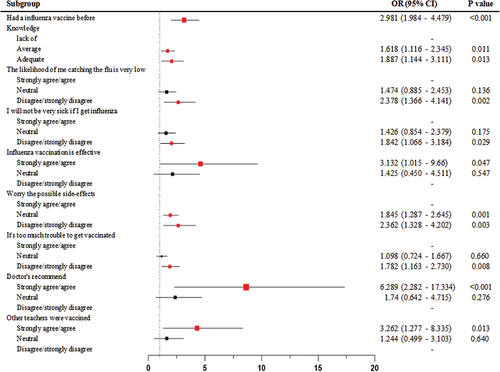

Further, the binary logistic regression model revealed that previous influenza vaccination history (OR = 2.981, 95% CI:1.984–4.479, p < .001), the one who had average level of knowledge (OR = 1.618, 95% CI:1.116–2.345, p = .011), who had adequate knowledge (OR = 1.887, 95% CI:1.144–3.111, p = .013), who disagree/strongly disagree (OR = 2.378, 95% CI:1.366–4.141, p = .002) that the likelihood of catching the influenza is very low, who disagree/strongly disagree (OR = 1.842, 95% CI:1.066–3.184, p = .029) that I will not be very sick if I get the flu, who strongly agree/agree (OR = 3.132, 95% CI:1.015–9.660, p = .047) influenza vaccine was effective, who remained neutral (OR = 1.845, 95% CI:1.287–2.645, p = .001) or disagreed/strongly disagreed (OR = 2.362, 95% CI:1.328–4.202, p = .003) that they worried the possible side-effects of influenza vaccine, who disagreed/strongly disagreed (OR = 1.782, 95% CI:1.163–2.730, p = .008) that it was too much trouble to get vaccinated, who strongly agree/agree (OR = 6.289, 95% CI:2.282–17.334, p < .001)to the doctor’s recommend, who strongly agree/agree (OR = 3.262, 95% CI:1.277–8.335, p = .013) that I would also be vaccinated as long as other teachers were vaccinated, were had higher possibility to accept influenza vaccination (See ).

Discussion

Our study investigated the teachers’ influenza vaccination coverage in Hangzhou, China, and explored the influencing factors of influenza vaccination acceptance. The findings showed that 5.9% of junior high school teachers self-reported having received an influenza vaccination. Meanwhile, 52.9% of teachers had the intention to receive influenza vaccine. Factors influencing teachers to accept influenza vaccine were whether had an influenza vaccine before, the level of influenza and influenza vaccine knowledge, the beliefs for the likelihood of catching flu, the severity of getting flu, the effectiveness of influenza vaccine, the possibility of side effects after vaccination, and the troublesome of vaccination, doctors’ recommendation, as well as the vaccination of other teachers.

The current study found that the influenza vaccination coverage among teachers was 5.9%, which was similar to that among teachers in Poland (4.5%)Citation12 and Czech Republic (6%)Citation13 and much lower than that in Greece (34.8%)Citation21 and America (55%).Citation15 This indicated that teachers’ influenza vaccination coverage varied widely around the world. According to the previous studies, the influenza vaccination coverage for whole population was 3.7% in Poland,Citation12 5% in Czech Republic,Citation13 5.7% in China,Citation25 51.9% in Greece,Citation26 and 42% in American.Citation27 Therefore, it seemed that there was a positive correlation between teacher influenza vaccination and the whole population influenza vaccination. Furthermore, compared teachers with HCWs, teachers’ influenza vaccination coverage tended to be lower than HCWs. Studies shown that 32.2% physicians, 19.9% nurses in PolandCitation28 and 19.5%-20.8% Polish primary healthcare patients stated vaccinated.Citation29,Citation30 In Greece and America, where influenza vaccinations are mandatory for HCWs, the influenza vaccination rate for HCWs were 74%Citation31 and 67%,Citation15 respectively. In China, the vaccination of HCWs is voluntary, and studiesCitation25 showed that the influenza vaccination coverage among teachers was 14.0%. HCWs and teachers were also highly educated people, and their ability to acquire knowledge might not differ. We inferred that the differences in vaccination rates might be due to, first, doctors were exposed to the virus and more likely to get the flu than teachers, second, for professional requirements, doctors might knew more knowledge about the flu than teachers. Furthermore, compulsory vaccination could greatly improve the influenza vaccination rate. In many countries, such as America, Greece, etc., influenza vaccinations are mandatory for HCWs.Citation15,Citation31 At present, some countries such as Estonia, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Poland in the world have included teachers in the recommended influenza vaccination group.Citation32 In the further, whether teachers need to include in the compulsory vaccination group needs further research and evaluation.

Studies had shown that teachers’ intention to receive influenza vaccination were 26% in Czech Republic,Citation13 9.2% in Poland,Citation12 and 53.9% in Greece.Citation14 From these data, it could be seen that teachers’ willingness to vaccinate in different countries were far greater than their actual vaccination rate. The same was true in China. In this study we found that 52.9% of teachers in China were willing to receive influenza vaccination, much higher than the actual influenza vaccination rate of 5.9%. These finding suggest that there was a greater need to turn teachers’ willingness into action. Further research is need to explore the mechanisms and relevance behind the influenza vaccination intention and behavior.

Vaccination is part of the “broader social world.”Citation33 In particular, in the era of media, constant exposure to the media had a large impact on the public’s inclination to get immunized.Citation34 In this study, we found that the top three most used information obtaining channels teachers used were websites, TV/radio, and social media. Website, such as Google, Baidu, etc., is a platform that requires people to search actively to obtain information, while social media, such as WeChat, Weibo, etc., is more passive acquisition, obtaining information from browsing or interaction. Thus, we could infer that teachers had the initiative to acquire knowledge of influenza vaccine, and authorities could publish more vaccine related information through the website. In addition, website and social media both belong to new media, which accounted for the vast majority of information obtaining channels for teachers in this study. This was consistent with the way people get information today.Citation35 In this study we also found that there were no differences in information obtaining channels between teachers who accept or hesitate to get influenza vaccine. Previous researches on vaccines showed that receiving health information from various sources had both beneficial and negative effects on immunization.Citation36,Citation37 Therefore, with respect to the acceptance of teachers to vaccinate, more attention should be paid to the content of the channels rather than to the channels through which information was obtained.

This study found that people who had been vaccinated before were 2.981 times more likely to accept influenza vaccination than those who had not been received influenza vaccine before. The result were in line with previous studies in different populations, such older people,Citation38,Citation39 HCWs,Citation40,Citation41 children’s guardians,Citation42 etc. It was possible that those who had received the influenza vaccine were more likely to trust the safety and effectiveness of the influenza vaccine, making them more willing to receive it again. Thus, Influenza vaccination campaigns should focus on people who had never been vaccinated against influenza.

Knowledge plays a very important role in vaccination intentions. The current study found that the teachers’ knowledge was at a relatively high level. Majority of teachers had the average and above level of knowledge. Most of teachers were familiar with the differences between flu and cold, how influenza spreads, and the symptom of influenza, but unfamiliar with the pathogen of influenza. A possible explanation for this might be that most of publicity and education were focus on the contents of disease transmission and prevention but not the virus, and people often did not care about the virus itself. In terms of influenza vaccine knowledge, the results showed that nearly half of teachers did not know the influenza vaccination time, and a third of teachers were unaware that the influenza vaccine could be administered annually. This result suggested that we should strengthen the publicity of influenza vaccine while promoting the prevention and control of influenza. Furthermore, this study found that knowledge of influenza and the influenza vaccine was one of the influencing factors of participants’ influenza vaccination acceptance. This accorded with previous studies, which showed that high level of knowledge on diseases and vaccines could increase people’s willingness to vaccinate.Citation12,Citation43 Nowadays, more and more attention has been paid to vaccine literacy for the study of vaccination intention and vaccine hesitation.Citation44 Vaccine literacy is an extension of vaccine knowledge, which refers to people’s capacity to obtain, process, and comprehend fundamental vaccination information and services as well as their capacity to weigh the risks and benefits of their actions and make decisions regarding their health.Citation45 Therefore, while improving people’s knowledge of influenza and influenza vaccine, it is more important to improve people’s vaccine literacy. Future research is needed to reach deeper into teachers based on the definition of vaccine literacy.

The Health Belief Model is designed to identify factors that could affect an individual’s health-related behaviors. In the dimensions of perceived susceptibility and severity, teachers who believed they had high possibility to get flu and had serious consequences were more likely to accept the influenza vaccination. This result was also reported by Perio in American teachers.Citation15 JanzCitation19 indicated that knowledge was at least somewhat correlated with perceived susceptibility and severity, both of which had a substantial cognitive component. Therefore, we needed more ways to make teachers aware of influenza susceptibility and severity. In the benefit and barrier dimensions, teachers who disagreed with the negative effects of the influenza vaccine and thought it was effective were more likely to accept the vaccination. These findings were also found among teachers in Poland,Citation12 GreeceCitation14 and America,Citation15 and were similar to results from the study of HCWs,Citation46 elders,Citation47 and other group of people.Citation48,Citation49 A belief in the efficacy and safety of vaccines was a sign of vaccine confidence.Citation50 Increasing vaccine confidence could increase acceptance of vaccines. Therefore, focused for raising the influenza vaccine confidence of teachers should be encouraged.Citation51–53 In addition, in this study we found that teachers who disagree that there was trouble to get influenza vaccine were more likely to accept influenza vaccination. This finding was also reported by RosenstockCitation54 who indicated that action was more likely to be taken when the readiness to act was high and the negative aspects (barrier) were seen as relatively weak, and vice versa. One study from PolandCitation12 reported that, teachers’ acceptance for influenza vaccination increased by facilitate inoculation within a school environment, during working hours. In the dimension of cue to action, this study shown that the recommendation from doctors played a part in increasing vaccination acceptance. This result was also found among teachers in Greece.Citation14 Indeed, numerous studies had demonstrated that people’s willingness to receive vaccinations was significantly positively impacted by a doctor’s suggestion.Citation55–57 Therefore, doctors should take on the responsibility of educating the public, including teachers, and should be made aware and work synergistically with national health authorities in promoting vaccinations. It was worth noting that in this study we found that teachers were more likely to accept influenza vaccination if other teachers vaccinated. This was also common in other vaccine willingness studies among different people.Citation58–60 Howard Gola et al.Citation61 explained this phenomenon with social cognition theory. People would imitate the acts of people they were familiar with and were more influenced by messages from people in their own group than by messages from outsiders.Citation62 Schmelz et al.Citation63 reported that if others had expressed a preference for vaccination, or if vaccination had been administered without negative consequences, or even just via exposure to more persons who have received vaccinations, people gained a more favorable opinion of vaccination. Therefore, when taking intervention measures, in addition to individual intervention, we should also pay attention to the influence of external environmental factors on individual health behaviors, and choose the best person to deliver the message and create a connection with other group people.Citation62

The study had a number of limitations. In the sampling process, teachers from rural areas participated in the survey were more actively. Therefore, although the number of surveys far exceeds the calculated sample size, teachers from rural areas accounted for the vast majority in this study, which would affect the representativeness of the research object. In addition, most of teachers were not in charge of class, which might reduce the influence of this factor on the results. Second, Since the survey of junior high school teachers was not representative of all teachers, it was necessary to conduct research on other teachers, including elementary, high school and college teachers. Third, given that the information was gathered only from teacher reports, recall bias problems about vaccine uptake could not be completely ruled out. Furthermore, due to the limitation of sample size, the study of influencing factors in different living area was not conducted. In the future, the influencing factors of acceptance of influenza vaccine among teachers in different regions could be further studied.

Conclusion

Teachers in China had disturbingly low rates of influenza vaccination, but their willingness to vaccinate was relatively high. Our results suggested that influenza vaccine acceptance among teachers was associated with whether receive influenza vaccine before, knowledge, the beliefs for the likelihood of catching flu, the severity of getting flu, the effectiveness of influenza vaccine, the possibility of side effects after vaccination, and the troublesome of vaccination, doctors’ recommendation, as well as the vaccination of other teachers. Further research on the relationship between high acceptance and low vaccination rates is needed in the future so that more teachers actually receive the influenza vaccine, and performed on a nationwide scale, in all styles of educational facilities, would be highly beneficial.

Authorship contribution statement

WG, YL, and JC contributed to the conception and design of the study. QC, JuW, XC, WJ, and JiW contributed to the acquisition of data. JD and XiZ supervised the study. YX, XZ, ZL, and YY performed the statistical analysis and interpreted the results. QX and LG managed ethical approval. This article was written by all of the authors, who also gave their final approval to the submitted version after revising it critically for significant intellectual substance.

Ethics approval

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the Hangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all the teachers who participated in this study, and all the colleagues who have given me generous support and helpful advice during the period of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ghebrehewet S, MacPherson P, Ho A. Influenza. BMJ. 2016;355:i6258. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6258.

- World Health Organization. Vaccines against influenza: WHO position paper – May 2022; 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer9719.

- Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Ferroni E, Rivetti A, Di Pietrantonj C. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD001269. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub6.

- World Health Organization. Influenza (seasonal); 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal).

- Grohskopf BLA, Blanton LH, Ferdinands JM, Chung JR, Broder KR, Talbot HK, Morgan RL, Fry AM. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices — United States, 2022–23 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71(1):1–10. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7101a1.

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Technical guidelines for seasonal influenza vaccination in China, 2022–2023; 2022. https://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/bl/lxxgm/jszl_2251/202208/t20220825_260956.html.

- Huiberts A, van Cleef B, Tjon ATA, Dijkstra F, Schreuder I, Fanoy E, van Gageldonk A, van der Hoek W, van Asten L. Influenza vaccination of school teachers: a scoping review and an impact estimation. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0272332. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0272332.

- Asihaer Y, Sun M, Li M, Xiao H, Amaerjiang N, Guan M, Thapa B, Hu Y. Predictors of influenza vaccination among Chinese middle school students based on the health belief model: a mixed-methods study. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(11):10. doi:10.3390/vaccines10111802.

- Plutzer E, Warner SB. A potential new front in health communication to encourage vaccination: health education teachers. Vaccine. 2021;39(33):4671–7. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.06.050.

- Ozturk FO, Tezel A. Health literacy and COVID-19 awareness among preservice primary school teachers and influencing factors in Turkey. J Sch Health. 2022;92(12):1128–36. doi:10.1111/josh.13231.

- Neuzil KM, Hohlbein C, Zhu Y. Illness among schoolchildren during influenza season: effect on school absenteeism, parental absenteeism from work, and secondary illness in families. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(10):986–91. doi:10.1001/archpedi.156.10.986.

- Ganczak M, Kalinowski P, Drozd-Dabrowska M, Biesiada D, Dubiel P, Topczewska K, Molas-Biesiada A, Oszutowska-Mazurek D, Korzeń M. School life and influenza immunization: a cross-sectional study on vaccination coverage and influencing determinants among polish teachers. Vaccine. 2020;38(34):5548–55. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.067.

- Pavlasova L, Vojir K. Influenza and influenza vaccination from the perspective of Czech pre-service teachers: knowledge and attitudes. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2021;29(3):177–82. doi:10.21101/cejph.a6670.

- Gkentzi D, Benetatou E, Karatza A, Kanellopoulou A, Fouzas S, Lagadinou M, Marangos M, Dimitriou G. Attitudes of school teachers toward influenza and COVID-19 vaccine in Greece during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(10):3401–7. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1945903.

- De Perio MA, Wiegand DM, Brueck SE. Influenza vaccination coverage among school employees; assessing knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. J Sch Health. 2014;84(9):586–92. doi:10.1111/josh.12184.

- Davidhiza R. Critique of the health-belief mode! J Adv Nurs. 1983;8:5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1983.tb00473.x.

- Rosenstock IM. Why people use health services. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(3):33. doi:10.2307/3348967.

- Corace KM, Srigley JA, Hargadon DP, Yu D, MacDonald TK, Fabrigar LR, Garber GE. Using behavior change frameworks to improve healthcare worker influenza vaccination rates: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2016;34(28):3235–42. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.071.

- Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health belief model; a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi:10.1177/109019818401100101.

- China CPsGotPsRo. Major adjustment! China will manage COVID-19 with measures against class B infectious diseases, instead of class a infectious disease; 2022. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-12/27/content_5733672.htm.

- La Vecchia C, Negri E, Alicandro G, Scarpino V. Attitudes towards influenza vaccine and a potential COVID-19 vaccine in Italy and differences across occupational groups, September 2020. Med Lav. 2020;111(6):445–8. doi:10.23749/mdl.v111i6.10813.

- Wong LP, Alias H, Wong PF, Lee HY, AbuBakar S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16:2204–14. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1790279.

- Shahrabani S, Benzion U, Yom Din G. Factors affecting nurses’ decision to get the flu vaccine. Eur J Health Econ. 2009;10(2):227–31. doi:10.1007/s10198-008-0124-3.

- Nagy-Vincze M, Béldi T, Szabó K, Vincze A, Miltényi-Szabó B, Varga Z, Varga J, Griger Z. Incidence, features, and outcome of disease relapse after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Muscle Nerve. 2023 May;67(5):371–7. doi:10.1002/mus.27811.

- Wang L, Su XG, Cui Y, Yin WD, He B. Survey on situation and cognition of influenza vaccination among population in six provinces of China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:4. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.03.013.

- Chen C, Liu X, Yan D, Zhou Y, Ding C, Chen L, Lan L, Huang C, Jiang D, Zhang X, et al. Global influenza vaccination rates and factors associated with influenza vaccination. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;125:153–63. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2022.10.038.

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2012-13 influenza season; 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1213estimates.htm.

- Report SRA. Determinants of vaccine hesitancy among poles; 2019. https://www.medexpress.pl/zbadano-przyczyny-niecheci-polakow-do-szczepien-przeciw-grypie/71702.

- Nessler K, Krzton-Krolewiecka A, Chmielowiec T, Jarczewska D, Windak A. Determinants of influenza vaccination coverage rates among primary care patients in Krakow, Poland and the surrounding region. Vaccine. 2014;32(52):7122–7. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.10.026.

- Kardas P, Zasowska A, Dec J, Stachurska M. Reasons for low influenza vaccination coverage – a cross-sectional survey in Poland. Croat Med J. 2011;52(2):126–33. doi:10.3325/cmj.2011.52.126.

- Rachiotis G, Papagiannis D, Malli F, Papathanasiou IV, Kotsiou O, Fradelos EC, Daniil D, Gourgoulianis KI. Determinants of influenza vaccination coverage among Creek Health care workers amid COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Dis Rep. 2021;13:757–62. doi:10.3390/idr13030071.

- European centre for disease prevention and control. Seasonal influenza vaccination In Europe.[EB/OL].(2015-7)[2023-9-16]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/Seasonal-influenza-vaccination-Europe-2012-13.pdf.

- Poltorak M, Leach M, Fairhead J, Cassell J. ‘MMR talk’ and vaccination choices: an ethnographic study in Brighton. Social Sci Med. 2005;61(3):709–19. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.014.

- Huang C, Yan D, Liang S. The relationship between information dissemination channels, Health belief, and COVID-19 vaccination intention: evidence from China. J Environ Public Health. 2023;2023:6915125. doi:10.1155/2023/6915125.

- Choi J, Tami-Maury I, Cuccaro P, Kim S, Markham C. Digital health interventions to improve adolescent HPV vaccination: a systematic review. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11(2). doi:10.3390/vaccines11020249.

- Gehrau V, Fujarski S, Lorenz H, Schieb C, Blöbaum B. The impact of Health information exposure and source credibility on COVID-19 vaccination intention in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4678. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094678.

- Yang X, Wei L, Liu Z. Promoting COVID-19 vaccination using the Health belief model: does information acquisition from divergent sources make a difference? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):3887. doi:10.3390/ijerph19073887.

- Kharroubi G, Cherif I, Bouabid L, Gharbi A, Boukthir A, Ben Alaya N, Ben Salah A, Bettaieb J. Influenza vaccination knowledge, attitudes, and practices among Tunisian elderly with chronic diseases. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:700. doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02667-z.

- Prada-García C, Fernández-Espinilla V, Hernán-García C, Sanz-Muñoz I, Martínez-Olmos J, Eiros JM, Castrodeza-Sanz J. Attitudes, perceptions and practices of influenza vaccination in the adult population: results of a cross-sectional survey in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19. doi:10.3390/ijerph191711139.

- Alame M, Kaddoura M, Kharroubi S, Ezzeddine F, Hassan G, Diab El-Harakeh M, Al Ariqi L, Abubaker A, Zaraket H. Uptake rates, knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward seasonal influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in Lebanon. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(11):4623–31. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1948783.

- Youssef D, Berry A, Youssef J, Abou-Abbas L. Vaccination against influenza among Lebanese health care workers in the era of coronavirus disease 2019. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):120. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-12501-9.

- Wu J, Wei Z, Yang Y, Sun X, Zhan S, Jiang Q, Fu C. Gap between cognitions and behaviors among children’s guardians of influenza vaccination: the role of social influence and vaccine-related knowledge. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(1):2166285. doi:10.1080/21645515.2023.2166285.

- Abdullahi LH, Kagina BM, Cassidy T, Adebayo EF, Wiysonge CS, Hussey GD. Knowledge, attitudes and practices on adolescent vaccination among adolescents, parents and teachers in Africa: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2016;34(34):3950–60. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.023.

- Zhang E, Dai Z, Wang S, Wang X, Zhang X, Fang Q. Vaccine literacy and vaccination: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2023;68:1605606. doi:10.3389/ijph.2023.1605606.

- Ratzan SC. Vaccine literacy: a new shot for advancing health. J Health Commun. 2011;16(3):227–9. doi:10.1080/10810730.2011.561726.

- Hall CM, Northam H, Webster A, Strickland K. Determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination hesitancy among healthcare personnel: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31(15–16):2112–24. doi:10.1111/jocn.16103.

- Kan T, Zhang J. Factors influencing seasonal influenza vaccination behaviour among elderly people: a systematic review. Public Health. 2018;156:67–78. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2017.12.007.

- Nichol B, McCready JL, Steen M, Unsworth J, Simonetti V, Tomietto M, Abbasi-Kangevari M. Barriers and facilitators of vaccine hesitancy for COVID-19, influenza, and pertussis during pregnancy and in mothers of infants under two years: an umbrella review. PLoS One. 2023;18(3):e0282525. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0282525.

- Chong HJ, Jang MK, Lockwood MB, Park C. Health belief model constructs affect influenza vaccine Uptake in kidney transplant recipients. West J Nurs Res. 2022;45(5):395–401. doi:10.1177/01939459221136354.

- Baldwin AS, Tiro JA, Zimet GD. Broad perspectives in understanding vaccine hesitancy and vaccine confidence: an introduction to the special issue. J Behav Med. 2023;46(1–2):1–8. doi:10.1007/s10865-023-00397-8.

- Jongen CS, McCalman J, Bainbridge RG. The implementation and evaluation of health promotion services and programs to improve cultural competency: a systematic scoping review. Front Public Health. 2017;5:24. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2017.00024.

- MacDonald NE, Butler R, Dubé E. Addressing barriers to vaccine acceptance: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(1):218–24. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1394533.

- Schoch-Spana M, Brunson EK, Long R, Ruth A, Ravi SJ, Trotochaud M, Borio L, Brewer J, Buccina J, Connell N, et al. The public’s role in COVID-19 vaccination: human-centered recommendations to enhance pandemic vaccine awareness, access, and acceptance in the United States. Vaccine. 2021;39(40):6004–12. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.059.

- Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the Health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2(4):328–35. doi:10.1177/109019817400200403.

- Wang X, Feng Y, Zhang Q, Ye L, Cao M, Liu P, Liu S, Li S, Zhang J. Parental preference for Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccination in Zhejiang Province, China: a discrete choice experiment. Front Public Health. 2022;10:967693. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.967693.

- Yuen WWY, Lee A, Chan PKS, Tran L, Sayko E. Uptake of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in Hong Kong: facilitators and barriers among adolescent girls and their parents. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194159. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0194159.

- Harris KM, Maurer J, Lurie N. Do people who intend to get a flu shot actually get one? J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(12):1311–13. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1126-2.

- Getachew T, Negash A, Degefa M, Lami M, Balis B, Debela A, Gemechu K, Shiferaw K, Nigussie K, Bekele H, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and associated factors among adult clients at public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia using the health belief model: multicentre cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(3):e070551. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070551.

- Wang Q, Yang L, Li L, Liu C, Jin H, Lin L. Willingness to vaccinate against herpes zoster and its associated factors across WHO regions: global systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023;9:e43893. doi:10.2196/43893.

- Siu JY, Cao Y, Shum DHK. Perceptions of and hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination in older Chinese adults in Hong Kong: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):288. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-03000-y.

- Howard Gola AA, Richards MN, Lauricella AR, Calvert SL. Building meaningful parasocial relationships between toddlers and media characters to teach early mathematical skills. Media Psychol. 2013;16(4):390–411. doi:10.1080/15213269.2013.783774.

- Drury J, Carter H, Ntontis E, Guven ST. Public behaviour in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: understanding the role of group processes. BJPsych open. 2020;7(1):e11. doi:10.1192/bjo.2020.139.

- Schmelz K, Bowles S. Overcoming COVID-19 vaccination resistance when alternative policies affect the dynamics of conformism, social norms, and crowding out. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118(25):118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2104912118.