?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Influenza is a significant public health threat associated with high morbidity and mortality globally. This study investigated the influenza vaccination rate (IVR) among community residents in Anhui province, China, and explored the association between participants’ influenza vaccination and their key sociodemographic characteristics, perception of COVID-19 as well as COVID-19 vaccination behavior. We found that the IVR among respondents in Anhui province was 27.85% in 2020. Regression analyses revealed that males (OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.01 ~ 1.96), residents with above middle school education (OR = 1.88, 95% CI: 1.04 ~ 3.39), considered themselves likely to be infected with COVID-19 (OR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.04 ~ 2.24), had received the COVID-19 vaccine (OR = 9.85, 95% CI: 3.49 ~ 27.78), did not plan to receive COVID-19 vaccine in the future (OR = 1.70, 95% CI: 1.17 ~ 2.47), and had no adverse reactions after COVID-19 vaccination (OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.04 ~ 2.27) were associated with a higher IVR. The acceptance of influenza vaccination was mainly associated with respondents’ gender, education, perception of COVID-19, history of COVID-19 vaccination in city and countryside community residents in Anhui province.

Introduction

Seasonal influenza is an acute respiratory infection caused by seasonal influenza virus.Citation1 Influenza causes a large number of cases and deaths worldwide through its seasonal wave of infection, and an average of 389,000 respiratory deaths are associated with influenza globally each year.Citation2 The Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) reported that even in mild years, influenza can result in 290,000 to 650,000 fatalities, 3 million to 5 million severe cases worldwide, and create more social and economic damage when it is an epidemic.Citation3 Influenza vaccination is the most cost-effective way to prevent and control influenza.Citation4 In addition, influenza vaccine is also a powerful tool to reduce the risk of serious illness, hospitalization, and death.Citation5,Citation6

The knowledge about IVR and its influencing factors is still limited in China. In recent years, studies on influenza vaccine in China mainly focused on influenza vaccine coverage and willingness to receive vaccine in some priority populations such as aged people and children.Citation7–9 It seems that there were few studies on influenza vaccination and influencing factors among community residents of Anhui in recent 10 years. Relatively few studies focused on general residents. Yao’s indicated that IVR in Chinese general people was only 2%.Citation10 A meta-analysis showed the pooled IVR in 35 studies conducted in mainland China was only 16.74%, significantly lower than neighboring countries, such as South Korea (35.61%) and Japan (32.62%).Citation11 Some studies showed that low perceived risk of influenza, poor knowledge of vaccines, non-confidence in vaccine safety, adverse reactions after vaccination, and inconvenient transportation for vaccination were main influencing factors on influenza vaccination.Citation12,Citation13

Currently, the Technical Guidelines for Influenza Vaccination in China (2022 ~ 2023) suggest that all persons ≥6 months of age who are willing to be vaccinated and have no relevant contraindications be vaccinated against influenza.Citation14 However, the influenza vaccine has not been included in the National Expanded Programme on Immunization (NEPI), which means that it is self-funded and optional in China. Only in a few large cities influenza vaccines can be provided for free to some priority populations such as senior citizens, children, and healthcare workers, which may motivate the targeted population to receive influenza vaccine.Citation15 Therefore, IVR may vary a lot because of the policy diversity in different areas. As a central province in China, Anhui province is an agricultural province with a large population (the total number of permanent residents in Anhui was 61.27 million) and a less developed economy.Citation16 Influenza vaccine is regarded as a non-NEPI vaccine in Anhui province. It is optional and self-funded for all types of residents including priority population.Citation17

COVID-19 has been managed as a Category B infectious disease in China since the beginning of 2023.Citation18 The WHO also has indicated that it no longer constitutes a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) though it is an ongoing health issue.Citation19 Moreover, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus (the director-general of the WHO) and Wannian Liang (the chief expert on COVID-19 prevention and control in China) emphasized that COVID-19 is no longer a PHEIC does not mean that it is not a global health threat or it can be ignored.Citation20,Citation21 It is still necessary to pay sufficient attention to the potential of COVID-19 emerging during influenza season.Citation22 And relevant research should be conducted to help understand the relationship between influenza vaccination and public perception of COVID-19, as well as COVID-19 vaccination behavior. The present study aimed to investigate IVR among community residents in Anhui province, China, and explored the association between participants’ influenza vaccination and their key sociodemographic characteristics, perception of COVID-19 as well as COVID-19 vaccination behavior.

Author introduction

The authors of this study, Mengjie Guo and Jian’ an Li (two first authors with equal contribution), are postgraduate students, majoring in Social Medicine and Health Management at the School of Health Management, Anhui Medical University. Mengjie Guo published a paper “Government-society collaborative participation in the prevention and control of major epidemics in rural communities: Case Analysis” (second author) in the Chinese Rural Health Service Administration. The corresponding author of this study, Li Wang, holds a doctorate degree and is an associate professor and master’s supervisor. Currently, she teaches at the School of Health Management, Anhui Medical University. Her research field primarily focused on vaccine hesitancy and public health policy. She has published more than 50 papers, including “Vaccine attitudes among young adults in Asia: a systematic review” in Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics (first author), “Understanding medical students’ practices and perceptions toward vaccination in China: A qualitative study in a medical university” in Vaccine (first author), “The development and reform of public health in China from 1949 to 2019” in Globalization & Health (first author) and “Experiences and Challenges of Implementing Universal Health Coverage with China’s National Basic Public Health Service Program: Literature Review, Regression Analysis, and Insider Interviews” in JMIR Public Health Surveill (third author).

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This study used data from a community survey done by the School of Health Management of Anhui Medical University in Anhui Province from July to December 2021 with a daily review of returned questionnaires. Participants who returned incomplete questionnaires were revisited or contacted on the following day.

Purposive sampling was used. Four countryside communities and four city communities were selected at first in Anhui province. Two of the four countryside communities were located in southern areas of Anhui, one close to the county city and the other in mountain areas far from the city. Another two countryside communities were in the northern areas of Anhui, one close to urban areas and one far away. Four city communities included one new community, one old community, one relocated community, and one unit community inFootnotea Hefei, the capital of Anhui province. Handy sampling had been used to select around 100 residents who meet the requirements (≥16 years old, conscious, and can cooperate with the survey without communication barriers) in each community.

The sample size, N, was estimated according to the formula:

where Z is equal to 1.96 (when α is 0.05, the 95% confidence interval) and α is 0.1. Based on previous studies, it was assumed that IVR in China (P) was 23.2%.Citation23 Since this study sampled eight communities, the group effect coefficient was 8, and the total sample size was 548. Considering the possible nonconforming feedback, the sample size should be at least 785, with a margin of 30%.

Questionnaire investigators were recruited from undergraduate and graduate students at the School of Health Services Management after passing the interview examination. Then they received unified training. Each respondent was interviewed face-to-face by one of the investigators. Before filling out the questionnaire, the purpose of the study was explained to the respondents, and informed consent was obtained. .

Study tool

A self-made questionnaire based on the literature review and expert consultation was applied to collect information. It was revised according to the comments from 30 respondents in the pretest survey. The final questionnaire included four sections:

Socio-demographic characteristics, including age, gender, marital status, community type, level of education and career;

Influenza vaccination (self-reported whether they had received at least one shot of influenza vaccine in 2020);

Perception about COVID-19, including cognition of the long-term existence of COVID-19, cognition of the possibility of infecting by COVID-19, cognition of the severity of COVID-19;

COVID-19 vaccination behavior, including the status of receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, the willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine in the future, as well as whether there are some adverse reactions after COVID-19 vaccination.

Statistical analysis

The database was established using Epi Data 3.1 software through double entry and verification. Stata SE 12 software was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the basic characteristics of the participants. Categorical variables were summarized by number and percent (%), and the comparisons between groups were calculated by the chi-square test, which was the univariate analysis. Univariate analysis is a two-variable analysis, including only one independent variable and one dependent variable. That means all questions in the questionnaire were independent variables (except for residents’ influenza vaccination), which were validated and analyzed separately with residents’ influenza vaccination (dependent variable).

Multivariate analysis includes a dependent variable with two or more independent variables. We used multivariate analysis to explore the association between influenza vaccination and the perception of COVID-19 as well as COVID-19 vaccination behavior. Residents’ influenza vaccination as the dependent variable and other questions in the questionnaire as independent variables are included in the regression model together. OR (95% CI) was calculated by logistic regression analysis for categorical variables. A two-tailed significance, defined as p-value <.05, was used for all analyses. In multivariate analysis, to ensure the stability of statistical results, some variables in which there are more than three categories were adjusted into two or three categories.

“Age” was re-categorized as “16 ~ 60” and “>60.” “Community type” was re-categorized as “countryside community” (including four communities in rural countryside) and “city community” (including four communities in city). And “educational level” was adjusted as two categories, “middle school or below” and “above middle school.” Moreover, “career” was adjusted to three categories, “farmer/freelance/other,” “work in government, public institutions or military” and “student.”

The perceptions about “the long-term existence of COVID-19 or nor,” “possibility of contracting COVID-19,” and “the severity of COVID-19” were re-categorized as “no” (including the former two categories shown in ) and “yes” (including the latter one or two categories shown in ). And “the status of receiving COVID-19 vaccine” was adjusted to “no” (not getting any COVID-19 vaccine) and “yes” (getting one or two shots of COVID-19 vaccines).

Table 1. Univariate analysis of influenza vaccination across sociodemographic characteristics in Anhui province, China in 2020.

Table 2. Univariate analysis of influenza vaccination rate and the perception of COVID-19 as well as COVID-19 vaccination behavior.

Results

Univariate analysis

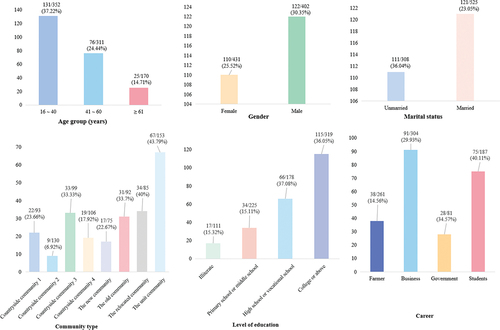

A total of 978 questionnaires were received in this survey, of which 833 (85.17%) were valid. Among them, 352 (42.26%) were aged between 16 ~ 40, 311 (37.33%) were aged between 41 ~ 60, and 170 (20.41%) were aged between 61 and above; 402 (48.26%) of the participants were males, and 431 (51.74%) were females. A total of 232 respondents reported that they received the influenza vaccine in 2020, and IVR in 2020 was 27.85%. See for details. Univariate analysis showed that there was a correlation in responses to all socio-demographic characteristics (p < .05) with influenza vaccination except for gender (p = .12). See for details.

Figure 2. Differences in IVR based on socio-demographic characteristics. 1) n/N and % indicate IVR in residents with different socio-demographic characteristics. Taking 131/352 and 37.22% in “age group (years)” as an example, n = 131 (the number of residents who have received influenza vaccine), N = 352 (the number of participants aged 16 ~ 40). 37.22% refers to the IVR of participants aged 16 ~ 40. 2) in the “community type,” countryside community 1 and countryside community 2 are villages located in southern Anhui. Countryside community 1 is close to the city and countryside community 2 is far from the city in the mountain area. Countryside community 3 and countryside community 4 are villages located in northern Anhui. Countryside community 3 is close to the city and countryside community 4 is far from the city. 3) in the “career,” business includes “employee, self-employed, and temporary worker.” Government including “work in government, public institutions, and military”.

Univariate analysis also showed that there was a correlation between influenza vaccination and some variables about the perception of COVID-19 as well as COVID-19 vaccination behavior (cognition of the long-term existence of COVID-19 (p = .02), the possibility of being infected by COVID-19 (p < .001), and status of the COVID-19 vaccination (p < .001)). See for details.

Multivariate analysis

The logistic regression assessed the association between influenza vaccination and the perception of COVID-19 as well as COVID-19 vaccination behavior, adjusting for age, gender, marital status, community type, level of education, and career. Only statistically significant variables were presented in .

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of influenza vaccine coverage rate among survey subjects (N = 883).

Those participants who thought they might be infected by COVID-19 were associated with a higher IVR (p = .031, 95% CI: 1.04 ~ 2.24). In addition, participants who have been vaccinated against COVID-19 had an IVR of 9.85 higher than others (p = .000, 95% CI: 3.49 ~ 27.78). Residents who would not to vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine in the future (p = .006, OR=1.70, 95% CI: 1.17 ~ 2.47) and who had no adverse effect after COVID-19 vaccination (p = .030, OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.04 ~ 2.27) had a higher IVR. Moreover, IVR was higher among males (p = .042, OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.01 ~ 1.96) and respondents with education above middle school (p = .036, OR = 1.88, 95% CI: 1.04 ~ 3.39). See for details.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this paper may be the first study to show IVR among residents in Anhui, and it may also be one of the few studies focusing on the relationship between residents’ influenza vaccination and COVID-19 perceptions and behaviors in China. We saw a relatively high influenza vaccine coverage among residents who considered themselves likely to be infected with COVID-19. Different COVID-19 behaviors were associated with IVRs. Males and participants with a higher education level were associated with a higher influenza vaccination coverage.

It was found that IVR among 833 respondents in 8 communities in Anhui was 27.85%, which is consistent with the study conducted in Hong Kong (29.1%), and higher than the pooled IVR of 16.74% in different studies.Citation11,Citation24 Chinese residents demonstrated a clear shift in attitudes toward influenza vaccination, with more enthusiasm for vaccination, under the background of COVID-19. The study conducted in Shanghai, China, showed that children’s willingness to receive influenza vaccine has increased significantly compared to that of pre-COVID-19-pandemic (78.4% VS 64.8%).Citation25

The great majority of influenza vaccinations were organized by schools or work units in China.Citation26 After the COVID-19 outbreak, most influenza vaccinations were still organized by schools and work units.Citation27 Silva discovered that students generally had positive attitudes toward influenza vaccine, and most students indicated that influenza vaccination was the best way to reduce healthcare visits for them.Citation28 This survey was conducted during the summer vacation. Compared to other studies, there were more students (22.45%). They may be organized to get the influenza vaccine by their schools. Compared to the IVR of elderly people in Taizhou, Zhejiang province (43.15%), we have a lower influenza vaccination rate.Citation29 The fact that some cities with higher development and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) have provided free influenza vaccine for the high-risk groups, has served as a remarkable stimulus for local influenza vaccination.Citation15 However, the strategy of free influenza vaccination for high-risk populations has not been implemented in Anhui province.

The study showed that there was a relationship between residents’ perception of susceptibility to COVID-19 virus with their influenza vaccination, which was consistent with Sulis G’s findings.Citation30 It was contended that perceived disease susceptibility and severity were significantly related to human health-related behaviors, and people with a stronger perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 infection had stronger motivation to receive influenza vaccine.Citation31,Citation32 In the early period of COVID-19 outbreak, great panic was generated globally, owing to its unknown virus characteristic. The public awareness of health risks was changed a lot by the emergence of COVID-19 in 2019.Citation33 People began to notice the seriousness of respiratory infectious diseases. COVID-19 and influenza have similar symptoms.Citation34 Therefore, the COVID-19 was also regarded as an “action prerequisite” for influenza vaccination. The findings provide suggestions to increase the willingness of residents to receive influenza vaccines, for example, by educating the public on the susceptibility and severity of COVID-19 and widely disseminating the positive effects of influenza vaccination on the prevention of COVID-19.

It was found that there was a significant association between respondents’ influenza vaccination and COVID-19 vaccination. Although we don’t know whether the respondents were vaccinated with influenza vaccine or COVID-19 vaccine first, it is worth noting that there is a certain relationship between them. It was indicated that prior vaccination experiences could shape positive attitudes toward vaccines and contribute to subsequent vaccine uptake.Citation35 Parker also reported that COVID-19 vaccination was positively correlated with influenza vaccination.Citation36 A study of influenza and COVID-19 vaccination found that residents who received the last seasonal influenza vaccine increased their willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine.Citation37

Our findings showed that 23.65% of respondents experienced adverse reactions after receiving COVID-19 vaccine, which was similar to previous research results.Citation38 They also had a lower IVR. It was found that adverse reactions after vaccination could cause vaccination refusal. Minor adverse reactions after vaccination might illustrate that the vaccine was arousing recipient’s immune system, while serious adverse reactions could pose a perilous danger, and thus cause vaccination hesitancy.Citation39–41 It is suggested that governments should conduct health education programs regarding adverse reactions after vaccination.

Our study also showed that the residents who expressed their reluctance to receive COVID-19 vaccines in the future exhibited a higher influenza vaccination rate compared to other people. It was notable that a rise in COVID-19 vaccination rate might be related to the decrease in IVR.Citation42 This might be a sign that people were likely to just choose one from influenza vaccine or COVID-19 vaccine. Simultaneous immunization with the COVID-19 vaccine and influenza vaccine is being seriously studied by academics.Citation43,Citation44 It was discussed that co-administration of COVID-19 and influenza vaccination could effectively reduce health system pressure because of organizing and providing vaccination services.Citation45,Citation46 The Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) in the United Kingdom recommended a synergistic program of vaccination for influenza and COVID-19, and indicated that this approach might maximize uptake of both vaccines.Citation47,Citation48 A Chinese study found immune interference for individuals was more significant when the influenza vaccine was co-administrated with a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.Citation49,Citation50 Vaccination strategy was suggested to consider the capacity of vaccination services in different regions and health conditions aimed at different populations.Citation44 It is also important to investigate residents’ attitudes toward co-administration, which could help policymakers and healthcare workers gain valuable insights into public perceptions, concerns, and preferences regarding receiving multiple vaccinations simultaneously.

It was suggested in the present study that a higher education level was associated with a higher influenza vaccination rate. It was consistent with prior studies which showed that higher educational levels were associated with increased acceptance and utilization of influenza vaccination.Citation51 However, Prada-Garcia figured out that the person with a lower education level was associated with a better willingness to vaccinate, because of their heightened conformity to medical advice and the influence of others in their decision-making process.Citation52 We argued that residents with higher education levels have a more comprehensive understanding of disease susceptibility and vaccine effectiveness during the epidemic of COVID-19. These may have a positive effect on their vaccination willingness.

Additionally, there was a significant correlation between gender and influenza vaccination. Studies showed that females were far more hesitant to receive vaccines than males.Citation53,Citation54 Such variances primarily stemmed from the physiological difference between males and females. Females roughly had twice the protective antibody reactions in vaccination as males and females typically experienced more frequent both local and general side adverse reactions to vaccines.Citation55 Women’s commonly perceived caregiving roles may delay their healthcare-seeking behaviors, and reduce their vaccination willingness.Citation54

The study has some limitations. First, it is not a random sampling. Therefore, it may be not prudent to extend our research findings to other cities in China without full discussion. Second, this paper was only a cross-sectional study. The individual’s perception and willingness toward influenza vaccine might change over time, and it was limited in establishing a causal relationship between influenza vaccination and sociodemographic variables, the perception of COVID-19, as well as COVID-19 vaccination behavior.

Conclusion

Although public enthusiasm for influenza vaccination has increased a little after the COVID-19 outbreak, there is still a large gap between the influenza vaccination rate in China and recommended by the WHO (75%).Citation56 The provision of free influenza vaccines remains limited, catering solely to certain populations in China. Our study showed that the higher IVR was associated with a better perception of COVID-19 and fewer adverse reactions to COVID-19 vaccination. The lower IVR was among residents who would continue to receive COVID-19 vaccine in the future, which has not been discussed in other studies.

The government should thoroughly examine the feasibility of simultaneous immunization with COVID-19 and influenza vaccines. Additionally, there is a need to enhance the supply of influenza vaccines to meet the increased demand. This can also involve incorporating the influenza vaccine into the NEPI, which would help ensure wider accessibility and coverage. Furthermore, providing monitoring and assistance for residents who experience adverse reactions after vaccination is crucial. Improving the satisfaction of residents in the whole process of vaccination and encouraging them, especially the high-risk residents, is also important.

To overcome the inherent limitations of cross-sectional analysis, continuing this study and conducting cohort studies in the future are necessary. We should also expand the scope of this study to reduce bias and make study results more representative.

Author contributions

MG and JL contributed equally to this work. LW and RC designed the study described in this article. JL and YW conducted the investigation and participated in data collection, and GC oversaw all aspects of data collocation. MG conducted the statistical analyses, and LW and JL participated in some of the statistical analyses. MG and JL wrote the preliminary and the corrected versions of the manuscript with advice from RC and LW. All authors contributed to the study design, conduct of the study, and the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Biomedical Ethics Committee at Anhui Medical University (IRB number: 20210614). Informed consent to utilize the collected information for research purposes was obtained from all participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

[a] The new community is defined as a community newly developed in the past 10 years, and usually located in the new investment and development zone in the city. Old community refers to community that has been built and used for more than 10 years and is generally located in old downtown in the city. The relocated community means a community built by the government for resettling residents whose own houses were used for public affairs. Unit community refers to the community built by the work unit to solve its employees’ living and housing problems, and most of the residents in the community are employees from the same work unit.

References

- World Health Organization. Influenza seasonal. Published 2023 [accessed 2023 Aug 19]. https://www.who.int/health-topics/influenza-seasonal#tab=tab_1.

- Paget J, Spreeuwenberg P, Charu V, Taylor RJ, Iuliano AD, Bresee J, Simonsen L, Viboud C. Global mortality associated with seasonal influenza epidemics: new burden estimates and predictors from the GLaMOR project. J Glob Health. 2019;9(2):020421. doi:10.7189/jogh.09.020421.

- World Health Organization. GISRS laid the foundation for protection through collaboration. Published 2022 [accessed 2023 Mar 26]. https://www.who.int/news/item/29-07-2022-gisrs-laid-the-foundation-for-protection-through-collaboration.

- Li J, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Liu L. Influenza and universal vaccine research in China. Viruses. 2022;15(1):116. doi:10.3390/v15010116.

- Davis TC, Vanchiere JA, Sewell MR, Davis AB, Wolf MS, Arnold CL. Influenza and COVID-19 vaccine concerns and uptake among patients cared for in a safety-net health system. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13:21501319221136361. doi:10.1177/21501319221136361.

- Loeb M, Roy A, Dokainish H, Dans A, Palileo-Villanueva LM, Karaye K, Zhu J, Liang Y, Goma F, Damasceno A, et al. Influenza vaccine to reduce adverse vascular events in patients with heart failure: a multinational randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [published correction appears in Lancet Glob Health. 2022 Nov 30]. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(12):e1835–9. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00432-6.

- Hou Z, Guo J, Lai X, Zhang H, Wang J, Hu S, Du F, Francis MR, Fang H. Influenza vaccination hesitancy and its determinants among elderly in China: a national cross-sectional study. Vaccine. 2022;40(33):4806–15. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.06.063.

- Zhou S, Greene CM, Song Y, Zhang R, Rodewald LE, Feng L, Millman AJ. Review of the status and challenges associated with increasing influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(3):602–11. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1664230.

- Jiang M, Li P, Yao X, Hayat K, Gong Y, Zhu S, Peng J, Shi X, Pu Z, Huang Y, et al. Preference of influenza vaccination among the elderly population in Shaanxi province, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(9):3119–25. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1913029.

- Yao KH. Some thoughts on influenza vaccine and regular influenza vaccination for healthcare workers. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi (In Chinese). 2018;20(11):881–6. doi:10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2018.11.001.

- Chen C, Liu X, Yan D, Zhou Y, Ding C, Chen L, Lan L, Huang C, Jiang D, Zhang X, et al. Global influenza vaccination rates and factors associated with influenza vaccination. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;125:153–63. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2022.10.038.

- Fan J, Ye C, Wang Y, Qi H, Li D, Mao J, Xu H, Shi X, Zhu W, Zhou Y. Parental seasonal influenza vaccine hesitancy and associated factors in Shanghai, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(12):2109. Published 2022 Dec 9. doi:10.3390/vaccines10122109.

- Yu M, Yao X, Liu G, Wu J, Lv M, Pang Y, Xie Z, Huang Y. Barriers and facilitators to uptake and promotion of influenza vaccination among health care workers in the community in Beijing, China: a qualitative study. Vaccine. 2022;40(14):2202–8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.060.

- National Immunization Advisory Committee (NIAC) Technical Working Group (TWG) on Influenza Vaccination. Technical guidelines for seasonal influenza vaccination in China (2022-2023). Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2022;56(10):1356–86. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20220825-00840.

- Jiang X, Shang X, Lin J, Zhao Y, Wang W, Qiu Y. Impacts of free vaccination policy and associated factors on influenza vaccination behavior of the elderly in China: a quasi-experimental study. Vaccine. 2021;39(5):846–52. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.040.

- Zhou Y, He X, Li S, Bechir CM. Research on the coordination of fiscal structure and high-quality economic development: an empirical analysis with the example of Anhui province in China. PloS One. 2023;18(6):e0287201. Published 2023 Jun 15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0287201.

- Health Commission of Anhui Province. Guan Yu shi Si Jie Ren Da Yi Ci Hui Yi Di 0761 Hao Dai Biao Jian Yi Da Fu De Han (in Chinese). Published 2023 [accessed 2023 Sep 16]. https://wjw.ah.gov.cn/public/7001/56851441.html.

- Consulate General of the People’s Republic of China in Perth. COVID-19 Health Code NOT Required from 8 January 2023. Published 2022 [accessed 2023 Aug 20]. http://perth.china-consulate.gov.cn/eng/notc/202212/t20221230_10998616.htm.

- World Health Organization. Statement on the fifteenth meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic. Published 2023 [accessed 2023 Aug 20]. https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic.

- World Health Organization. WHO press conference on COVID-19 and other global health issues - 5 May 2023. Published 2023 [accessed 2023 May 15]. https://www.who.int/multi-media/details/who-press-conference-on-covid-19-and-other-global-health-issues---5-may–2023.

- Xin Hua She Xin Mei Ti (in Chinese). Zhuan Jia Jie Du Xin Guan Yi Qing Bu Zai Gou Cheng “Guo Ji Guan Zhu De Tu Fa Gong Gong Wei Sheng Shi Jian” De Yuan Yin. China: Baidu; Published 2023 [accessed 2023 May 15]. https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1765316597607051421&wfr=spider&for=pc.

- Majeed B, David JF, Bragazzi NL, McCarthy Z, Grunnill MD, Heffernan J, Wu J, Woldegerima WA. Mitigating co-circulation of seasonal influenza and COVID-19 pandemic in the presence of vaccination: A mathematical modeling approach. Front Public Health. 2023;10:1086849. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1086849.

- Wang Q, Yue N, Zheng M, Wang D, Duan C, Yu X, Zhang X, Bao C, Jin H. Influenza vaccination coverage of population and the factors influencing influenza vaccination in mainland China: a meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2018;36(48):7262–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.045.

- Sun KS, Lam TP, Kwok KW, Lam KF, Wu D, Ho PL. Seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among Chinese in Hong Kong: barriers, enablers and vaccination rates. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(7):1675–84. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1709351.

- Zhou Y, Tang J, Zhang J, Wu Q. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic and a free influenza vaccine strategy on the willingness of residents to receive influenza vaccines in Shanghai, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Jul 3;17(7):2289–92. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1871571.

- Qi D, Zhongyan W, Yu Z, Tongxin S, Xiaokun G, Xiaoshuang X, Yahui H, Lin W, Xin L. 2019 influenza vaccination in Tianjin Hexi district. Zhonghua Lao Nian Xin Nao Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi (In Chinese). 2021;23(4):391–3. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1009-0126.2021.04.015.

- Wu L, Guo X, Liu J, Ma X, Huang Z, Sun X. Evaluation of influenza vaccination coverage in Shanghai city during the 2016/17 to 2020/21 influenza seasons. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(5):2075211. doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2075211.

- Silva J, Bratberg J, Lemay V. COVID-19 and influenza vaccine hesitancy among college students. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2021;61(6):709–14.e1. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2021.05.009.

- Yan Q, Xiang Z, Chunhua Q, Yiwen X, Yiping C, Lianhua W, Xiaoxiao C. Coverage levels of influenza vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among ≥60-year-old population of Taizhou city after implementation of a free vaccination policy. Zhongguo Yi Miao He Mian Yi (In Chinese). 2022;28(2):204–7+237. doi:10.19914/j.CJVI.2022040.

- Sulis G, Basta NE, Wolfson C, Kirkland SA, McMillan J, Griffith LE, Raina P. Influenza vaccination uptake among Canadian adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of the Canadian longitudinal study on aging (CLSA). Vaccine. 2022;40(3):503–11. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.088.

- An PL, Nguyen HTN, Dang HTB, Huynh QNH, Pham BDU, Huynh G. Integrating Health behavior theories to predict intention to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Health Serv Insights. 2021;14:11786329211060130. doi:10.1177/11786329211060130.

- Yu Y, Ma YL, Luo S, Wang S, Zhao J, Zhang G, Li L, Li L, Tak-Fai Lau J. Prevalence and factors of influenza vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic among university students in China. Vaccine. 2022;40(24):3298–304. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.04.077.

- Sturm L, Kasting ML, Head KJ, Hartsock JA, Zimet GD. Influenza vaccination in the time of COVID-19: a national U.S. survey of adults. Vaccine. 2021;39(14):1921–8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.003.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): similarities and differences between COVID-19 and influenza. Published 2023 [accessed 2023 Sep 1]. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-similarities-and-differences-with-influenza.

- Du Y, Jin C, Jit M, Chantler T, Lin L, Larson HJ, Li J, Gong W, Yang F, Ren N, et al. Influenza vaccine uptake among children and older adults in China: a secondary analysis of a quasi-experimental study. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):225. Published 2023 Apr 13. doi:10.1186/s12879-023-08145-8.

- Parker AM, Atshan S, Walsh MM, Gidengil CA, Vardavas R. Association of COVID-19 vaccination with influenza vaccine history and changes in influenza vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2241888. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.41888.

- Dombrádi V, Joó T, Palla G, Pollner P, Belicza É. Comparison of hesitancy between COVID-19 and seasonal influenza vaccinations within the general Hungarian population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):2317. Published 2021 Dec 23. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-12386-0.

- Abu-Hammad O, Alduraidi H, Abu-Hammad S, Alnazzawi A, Babkair H, Abu-Hammad A, Nourwali I, Qasem F, Dar-Odeh N. Side effects reported by Jordanian healthcare workers who received COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(6):577. doi:10.3390/vaccines9060577.

- Mulligan MJ, Lyke KE, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Neuzil K, Raabe V, Bailey R, Swanson KA, et al. Phase I/II study of COVID-19 RNA vaccine BNT162b1 in adults [published correction appears in nature. 2021 Feb;590(7844): E26]. Nature. 2020;586(7830):589–93. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2639-4.

- Walsh EE, Frenck RW Jr, Falsey AR, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Neuzil K, Mulligan MJ, Bailey R, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA-Based covid-19 vaccine candidates. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2439–50. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2027906.

- Andrzejczak-Grządko S, Czudy Z, Donderska M. Side effects after COVID-19 vaccinations among residents of Poland. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(12):4418–21. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202106_26153.

- Leuchter RK, Jackson NJ, Mafi JN, Sarkisian CA. Association between COVID-19 vaccination and influenza vaccination rates. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(26):2531–2. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2204560.

- Domnich A, Orsi A, Trombetta CS, Guarona G, Panatto D, Icardi G. COVID-19 and seasonal influenza vaccination: cross-protection, co-administration, combination vaccines, and hesitancy. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022;15(3):322. doi:10.3390/ph15030322.

- Zhang T, Bai XF, Wang W, Liu XX, Zhang XX, Wang DY, Zhang SB, Chen ZP, He HQ, Huang ZY, et al. Consideration on implementation of co-administration of seasonal influenza and COVID-19 vaccines during pandemic in China. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2022;56(2):103–7. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20211203-01117.

- Lazarus R, Baos S, Cappel-Porter H, Carson-Stevens A, Clout M, Culliford L, Emmett SR, Garstang J, Gbadamoshi L, Hallis B, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of concomitant administration of COVID-19 vaccines (ChAdox1 or BNT162b2) with seasonal influenza vaccines in adults in the UK (ComFlucov): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 4 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10318):2277–87. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02329-1.

- Toback S, Galiza E, Cosgrove C, Galloway J, Goodman AL, Swift PA, Rajaram S, Graves-Jones A, Edelman J, Burns F, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of a COVID-19 vaccine (NVX-CoV2373) co-administered with seasonal influenza vaccines: an exploratory substudy of a randomised, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(2):167–79. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00409-4.

- UK Government. Independent report. JCVI interim advice: potential COVID-19 booster vaccine programme winter 2021 to 2022. Published 2021. [accessed 2023 Aug 27]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/jcvi-interim-advice-on-a-potential-coronavirus-covid-19-booster-vaccine-programme-for-winter-2021-to-2022/jcvi-interim-advice-potential-covid-19-booster-vaccine-programme-winter-2021-to-2022.

- McCauley J, Barr IG, Nolan T, Tsai T, Rockman S, Taylor B. The importance of influenza vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2022;16(1):3–6. doi:10.1111/irv.12917.

- Xie Y, Tian X, Zhang X, Yao H, Wu N. Immune interference in effectiveness of influenza and COVID-19 vaccination. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1167214. Published 2023 Apr 19. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1167214.

- Shenyu W, Xiaoqian D, Bo C, Xuan D, Zeng W, Hangjie Z, Qianhui Z, Zhenzhen L, Chuanfu Y, Juan Y, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccine (CoronaVac) co-administered with an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine: a randomized, open-label, controlled study in healthy adults aged 18 to 59 years in China. Vaccine. 2022;40(36):5356–65. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.07.021.

- Li K, Yu T, Seabury SA, Dor A. Trends and disparities in the utilization of influenza vaccines among commercially insured US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccine. 2022;40(19):2696–704. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.03.058.

- Prada-García C, Fernández-Espinilla V, Hernán-García C, Sanz-Muñoz I, Martínez-Olmos J, Eiros JM, Castrodeza-Sanz J. Attitudes, perceptions and practices of influenza vaccination in the adult population: results of a cross-sectional survey in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17). doi:10.3390/ijerph191711139.

- McElfish PA, Willis DE, Shah SK, Bryant-Moore K, Rojo MO, Selig JP. Sociodemographic determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, fear of infection, and protection self-efficacy. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211040746. doi:10.1177/21501327211040746.

- Morgan R, Klein SL. The intersection of sex and gender in the treatment of influenza. Curr Opin Virol. 2019;35:35–41. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2019.02.009.

- Sánchez-de PL, Ortiz de Lejarazu-Leonardo R, Castrodeza-Sanz J, Tamayo-Gómez E, Eiros-Bouza JM, Sanz-Muñoz I. Do vaccines need a gender perspective? Influenza says yes! Front Immunol. 2021;12:715688. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.715688.

- Ortiz JR, Yu SL, Driscoll AJ, Williams SR, Robertson J, Hsu JS, Chen WH, Biellik RJ, Sow S, Kochhar S, et al. The operational feasibility of vaccination programs targeting influenza risk groups in the World Health Organization (WHO) African and South-East Asian Regions. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(2):227–36. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab393.