ABSTRACT

Hypertension, a prevalent chronic disease, has been associated with increased COVID-19 severity. To promote the COVID-19 booster vaccination of hypertensive patients, this study investigated the willingness to receive boosters and the related influencing factors based on the health belief model (HBM model). Between June and October 2022, 453 valid questionnaires were collected across three Chinese cities. The willingness to receive a booster vaccination was 72.2%. The main factors that influenced the willingness of patients with hypertension to receive a booster shot were male (χ2 = 7.008, p = .008), residence in rural (χ2 = 4.778, p = .029), being in employment (χ2 = 7.232, p = .007), taking no or less antihypertensive medication (χ2 = 9.372, p = .025), with less hypertension-related comorbidities (χ2 = 35.888, p < .0001), and did not have any other chronic diseases (χ2 = 28.476, p < .0001). Amid the evolving COVID-19 landscape, the willingness to receive annual booster vaccination was 59.4%, and employment status (χ2 = 10.058, p = .002), and presence of other chronic diseases (χ2 = 14.256, p < .0001) are associated with the willingness of annual booster vaccination. Respondents with higher perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived self-efficacy, and lower perceived barriers were more willing to receive booster shots. The mean and median value of willingness to pay (WTP) for a dose of booster were 53.17 CNY and 28.31 CNY. Concerns regarding booster safety and the need for professional advice were prevalent. Our findings highlight the importance of promoting booster safety knowledge and health-related management among hypertensive individuals through professional organizations and medical specialists.

Introduction

Hypertension is a major global health concern, contributing to 8.5 million deaths from stroke, ischemic heart disease, other vascular diseases, and renal diseases.Citation1,Citation2 In 2019, the global age-standardized prevalence of hypertension in adults aged 30–79 years was 32% in women and 34% in men.Citation3 In China, about 23.2% (≈244.5 million) of the Chinese population ≥18 years has hypertension, and another 41.3% (≈435.3 million) has pre-hypertension between 2012 and 2015.Citation4 In 2018, the nationwide prevalence of hypertension and pre-hypertension increased to 27.5% and 50.9%, respectively.Citation5 Hypertensive patients are more susceptible to severe COVID-19 outcomes, necessitating booster vaccinations to build herd immunity and reduce illness burden.Citation6–11

As of March 2023, 183 vaccines were in clinical development, with 199 in pre-clinical stages, including various types such as inactivated, live attenuated, viral vector, protein subunit, RNA, DNA, and virus-like particle (VLP) vaccines.Citation12,Citation13 In China, inactivated COVID-19 vaccines, adenovirus vector vaccines (Ad5-nCoV), and protein subunit vaccines have been the most widely used. Stable hypertensive patients with blood pressure below 160/100 mmHg were recommended for vaccination, but hypertension has often been mistakenly considered a contraindication.Citation14 According to China CDC, 90% of the population has received full vaccination, and the percentage has remained stable since July 2022.Citation15 Due to waning immunity, a dose of booster vaccination has been proposed by health agencies on 2021.Citation16 However, the completion rates of booster doses are much lower. In a survey of older people (aged 60+) among China, the completion rates of booster doses were only 72.4%.Citation14 Nevertheless, previous studies show that people with hypertension are less willing to get a dose of COVID-19 booster than people in general (76.8% vs 91.1%).Citation17,Citation18 In general people, sociodemographic characteristics including age, gender, occupation, and education influence booster vaccine acceptance.Citation19 Confidence in the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines, and in the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 and its variants, significantly associated with willingness to accept COVID-19 booster.Citation18 In the hypertensive population, the preventive effect of the vaccine, vaccine safety, vaccine knowledge, presence of comorbidities, disease control, and antihypertensive treatments were the main factors that influenced the willingness of patients with hypertension to receive a booster dose.Citation17 Following the COVID-19 policy change, the government has started the second dose of booster immunization on December 13, 2022.Citation20 Amid the evolving COVID-19 landscape, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposed switching to annual coronavirus vaccine, mimicking flu model, which could considerably lower the long-term risk of infection.Citation21–23 The Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) of FDA stated that they anticipate assessing SARS-CoV-2 evolution at least annually and to discuss in the June of each year regarding strain selection for a fall vaccination. On June 15, 2023, they has advised manufacturers to update COVID-19 vaccines with a monovalent XBB 1.5 composition to use in the fall of 2023.Citation24

Vaccine hesitancy, the delay or refusal of vaccination despite availability, poses a major challenge to achieving global immunity against COVID-19.Citation25,Citation26 The Health Belief Model (HBM) is one of the most prominent public health frameworks for interpreting factors associated with why individuals’ behaviors and attitudes when faced with a threat to personal or community health, including perceived susceptibility, severity, benefit, barriers, and cues to action.Citation27 Many studies have shown that interventions targeting HBM constructs are highly effective in increasing COVID-19 vaccination rates in various populations.Citation28–31 Comorbidities, confidence in effectiveness of the vaccine, and confidence in safety of the vaccine were reported to affect the willingness to receive a booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine among hypertensive patients in Taizhou, China.Citation17 It remains still inconclusive whether hypertensive people in China are willing to receive a dose of booster, or even annual vaccination.

Apart from the willingness to vaccinate, the success of long-term vaccination is also closely related to willingness to pay (WTP).Citation32 To take an obvious example, the Chinese government categorizes vaccines into Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) vaccines and non-EPI vaccines.Citation33 EPI vaccines are fully covered by the government tax, and the vaccination rates are very high in China, such as HBV vaccine.Citation34 Nevertheless, non-EPI vaccines are self-funded, which has led to very low coverage rates, such as 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and influenza vaccine.Citation33,Citation35 In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese government has implemented a free nucleic acid test and free vaccination strategy. However, Chinese National Healthcare Security Administration announced that the National Medical Fund no longer subsidize routine nucleic acid amplification tests in 5/26/2022.Citation36 A long-term free vaccination program is financially challenging. It is uncertain whether the free vaccination policy will be adjusted to self-funded in the future in the light of the changing burden of COVID-19. To provide relevant information about social demand, access and financing for future COVID-19 vaccination, various studies were conducted to understand individuals’ WTP among general population.Citation32,Citation33,Citation37,Citation38 However, WTP among hypertensive population in China remains unknown.

This study aims to examine the acceptance rate of a dose of COVID-19 booster among hypertensive patients in China, using the HBM model to analyze the implications of vaccine hesitancy. Given the cohabitation of COVID-19 with humanity, the acceptance and influence factors of COVID-19 annual vaccinations were also explored. Considering the uncertain future of the government’s free immunization program, we explored the willingness to pay. Our findings will provide empirical evidence to improve COVID-19 booster delivery and control the pandemic.

Methods

Study design

This study is a web-based, multicenter cross-sectional survey aimed at investigating the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines and influencing factors among hypertensive patients. Based on the division of China’s seven major geographical regions, three regions, East China, Central China and Northwest China were selected for the survey through the simple random sampling method. The study was conducted from June 28 to October 24, 2022 in the most populous capital cities of these three regions: Beijing (North China), Zhengzhou (Central China), and Xi’an (Northwest China).

Participants

Study participants met the following inclusion criteria: 1) a diagnosis of hypertension, 2) aged 18 years or above, and 3) willingness to provide written informed consent to complete the survey. Exclusion criteria were applied to patients who were unable to effectively communicate with investigators, or failed to complete the questionnaire survey.

Recruitment and data collection

Hypertensive patients were recruited from the Heart Center and Beijing Key Laboratory of Hypertension at Beijing Chaoyang hospital, the Department of Cardiology at Xi’an No.1 hospital, and the Zhengzhou Jinshui District Jiujiu social work service center. Investigators introduced the study and invited hypertensive patients to complete an electronic questionnaire. Participants were informed of the survey’s anonymity, the strict confidentiality of their responses, and their rights to decline or withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. To ensure the authenticity of background characteristics, hypertension diagnosis certificates were verified in the medical records system. Data were collected via the online survey website, Jinshuju (www.jinshuju.net). For participants unable to complete the electronic questionnaires using cellphones, medical staff conducted interviews and filled out the questionnaires on their behalf. To prevent multiple submissions by the same individual, the software function restricted each cellphone to completing only one questionnaire.

Sample size planning

Assuming a 60% acceptance rate for the COVID-19 booster vaccination among hypertensive patients, a permissible error of 6%, and a 20% non-response rate, the target sample size for this study was 339. Sample size analysis was performed using PASS11.0 (NCSS, USA).

Measurements

Questionnaire development

A team of epidemiologists, behavioral health experts, and cardiovascular doctors developed the questionnaire based on a literature review and in-depth interviews with hypertensive patients. The questionnaire was tested on 20 hypertensive patients for intelligibility and readability before revisions were made. Reliability test was performed and the Cronbach’s alpha of the HBM scale was 0.80. These patients agreed that the questions were clear and of acceptable length, and they did not participate in the actual survey.

COVID-19 booster acceptance

The primary outcome was the acceptance of a dose of COVID-19 booster vaccination, which was defined based on the following questions: “Would you accept a dose of COVID-19 booster?.” The willingness to get regular COVID-19 boosters were also asked: “If SARS-CoV-2 coexists with humans, would you be willing to receive annual COVID-19 boosters?” Participants were classified as “vaccine acceptance” if they responded “have been vaccinated,” “strongly willing to,” or “willing to.” They were classified as “vaccine hesitant” if they responded “strongly refuse,” “refuse,” or “neutral.” Willingness to pay (WTP) was measured by using the following question: “If SARS-CoV-2 coexists with humans, and the government no longer provide free COVID-19 vaccination, would you be willing to pay for COVID-19 boosters?” In addition, the WTP values were measured using a one-item open-ended question: “What is the maximum amount that you are willing to pay for a dose of COVID-19 booster?”

Background characteristics

Background characteristics included three sections. The first section was sociodemographic characteristics, including age, gender, ethnicity, education level, marital status, residence, employment status, occupation, and annual income. The second section was hypertension history, including body mass index (BMI), time of hypertension, family history of hypertension, blood pressure, daily antihypertensive drugs, comorbidities associated with hypertension, and other chronic diseases. The third section was COVID-19 vaccination information, which were checked through apps Beijing jiankangbao, Shaanxi yimatong, and Zhenghaoban.

Perceptions of booster vaccination

This part was designed based on the health belief model (HBM), which has been widely used to understand the determinants of vaccination acceptance.Citation30 The questions included perceived susceptibility to omicron infection, perceived severity of COVID-19, perceived benefits of COVID-19 boosters, perceived barriers of COVID-19 boosters, perceived self-efficacy to engage in vaccination, and cue to action. All self-reported response options were evaluated using a five-point Likert scale and converted to binary variables. For example, “strongly agree” and “agree” were converted to “agree,” “neither agree nor disagree,” “strongly disagree” and “disagree” were converted to “disagree/neutral.”

External influences related to COVID-19 booster vaccination

Participants ranked factors influencing willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster and identified ways to encourage more hypertension patients to get vaccinated, given the booster’s safety, effectiveness, and necessity.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe background characteristics. We used mean ± standard deviation (SD) to describe the variable characteristics of normal distribution data, and for the skewed or unknown distribution data, we described using median and range interquartile. The categorical variables were described using composition ratio (%) or rate (%). Cronbach’s alpha for the HBM scale was obtained using reliability test. And chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests assessed differences regarding booster acceptance. T-tests compared continuous variables between acceptance and hesitation groups. To control for the impact of confounding bias, we adopted the multivariate analysis method. Univariate analysis and multivariable logistic regression based on the HBM model examined the relationship between influencing factors and booster acceptance. A two-tailed p value below .05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM, USA).

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing hospital. The approval letter number is 2021BJYYEC-299-02. All work was conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Characteristics of the study sample

During the study period, 533 hypertensive patients meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were invited to complete the survey. There were 80 patients who refused to finish the survey. Among them, 61 refused to participant, and 19 were eligible but unable to finish the survey after completing part of the questionnaire (). Reasons for non-participation or non-completion included lack of time, interest, and reluctance to disclose personal information. 453 provided written informed consent and completed the questionnaire. The overall response rate was 85.0%.

All the incomplete questionnaires were excluded from analysis, and 453 completed questionnaires were analyzed, with background characteristics presented in . The mean (SD) age was 58.4 ± 11.4 years, with 48.1% aged between 40–59 years. Participants were predominantly male (59.8%), Han ethnicity (93.2%), and urban residents (91.4%). College education or above accounted for 39.1%, and 87.2% were married. About 42.6% were employed full-time, part-time, or self-employed, and 39.3% had a monthly income between 1,000 and 4,999 CNY.

Table 1. Background characteristics of 453 participants.

Regarding hypertension status, 35.5% were diagnosed within the past 5 years, and 80.4% reported a family history. According to medical records and blood pressure measured before investigation, the blood pressure levels of participants were classified following the 2018 Chinese guidelines for prevention and treatment of hypertension.Citation39 43.0% were high normal (systolic blood pressure (SBP) 120–139 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) 80–89 mmHg). 93.1% of participants took antihypertensive drugs daily, and 61.8% of respondents took only one drug. 65.6% of participants did not suffer from hypertension-related comorbidities. Among the patients with hypertension-related comorbidities, hyperlipidemia was the most common comorbidity, with a prevalence rate of 16.6%. 93.4% had no other chronic diseases.

In terms of vaccination status, 51.0% received two doses of COVID-19 vaccines, and 85.7% received inactivated vaccines.

Basic characteristics and vaccination acceptance

As shown in , 27.8% (126/453) were hesitant to receive a booster vaccination. Hypertensive patients that were male (χ2 = 7.008, p = .008), residing in rural areas (χ2 = 4.778, p = .029), being employed (χ2 = 7.232, p = .007), taking fewer antihypertensive medications (χ2 = 9.372, p = .025), having fewer hypertension-related comorbidities (χ2 = 35.888, p<.0001), and not having other chronic diseases (χ2 = 28.476, p<.0001) were more willing to receive a dose of booster. Classification of blood pressure levels were also associated with the willingness to receive a dose of booster (χ2 = 12.134, p = .016), and patients with stage 3 high blood pressure had the lowest willing to receive a booster shot. The mean age of the booster hesitant group was significantly higher than that of the willing group (60.8 ± 11.7 vs 57.5 ± 11.1, p = .005).

Table 2. Frequency distribution and chi-square analysis of a dose of COVID-19 booster acceptance.

Similar results were found for annual vaccination. As seen in Supplementary Table S1, 40.6% (184/453) of the participants were hesitant about annual boosters. Among them, hypertensive patients that were employed (χ2 = 10.058, p = .002), and did not have any other chronic diseases (χ2 = 14.256, p < .0001) were more likely to receive COVID-19 boosters annually. Blood pressure levels were also associated with the willingness to get annual boosters (χ2 = 15.275, p = .004), and patients with stage 3 high blood pressure had the lowest willing to receive annual vaccination. The mean age of the annual boosters hesitant group was significantly higher than that of the willing group (60.3 ± 11.8 vs 57.1 ± 10.9, P = .003).

HBM factors and vaccination acceptance

Firstly, reliability test was performed for the 453 questionnaires, and the Cronbach’s alpha of the HBM scale was 0.82. presents univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis results based on HBM factors. People who believed that the COVID-19 was more severe in hypertensive people than general were more likely to accept the booster shot (aOR = 3.693, 95% CI: 2.231–6.114). Those who believed boosters can maintain the antibody level and strength protection (aOR = 6.458, 95% CI: 3.792–10.997), reduce the risk of omicron variants infection (aOR = 8.030, 95% CI: 4.635–13.911), reduce the risk of developing severe COVID syndrome (aOR = 5.996, 95% CI: 3.524–10.202), and efficacy of boosters to extend protection was stronger and longer in hypertension people compared with people without hypertension (aOR = 2.598, 95% CI: 1.598–4.222) had a higher likelihood to accept a COVID-19 vaccine. As for perceived barriers, hypertensive people who disagreed with that side effects of boosters were more severe in hypertension people (aOR = 2.908, 95% CI: 1.788–4.732), and boosters can aggravate the underlying disease of hypertension (aOR = 3.212, 95% CI: 1.962–5.259) were more likely to receive a booster. In the perceived self-efficacy part, hypertensive patients that thought it was easy to get the same type (aOR = 2.598, 95% CI: 1.424–4.741), as well as another type (aOR = 4.622, 95% CI: 2.798–7.634) of vaccine as the one received before were more willing to receive a booster vaccination.

Table 3. Factors associated with a dose of booster vaccination acceptance.

Similar results were obtained in annual booster vaccinations (Supplementary Table S2). The annual vaccination willingness was stronger in the group who thought that the severity of COVID-19 was higher in hypertensive people (aOR = 1.654, 95% CI: 1.110–2.463). The agreement with that vaccine could maintain antibody levels and enhance protection (aOR = 5.338, 95% CI: 3.229–8.825), could reduce the risk of omicron infection (aOR = 5.401, 95% CI: 3.255–8.961), could reduce the risk of severe COVID-19 syndrome (aOR = 4.654, 95% CI: 2.833–7.647), and efficacy of boosters to extend protection was stronger and longer in hypertension people compared with people without hypertension (aOR = 1.574, 95% CI: 1.064–2.329) were positively associated with the willingness to vaccinate annually. The group that disagreed that the side effects of boosters were more severe in hypertensive people and that the vaccine would aggravate the underlying disease of hypertension was more willing to get annual doses of boosters. In addition, People with a higher level perceived self-efficacy were more likely to accept annual vaccination (aOR = 2.328, 95% CI: 1.208–4.489).

External influences related to COVID-19 booster vaccination

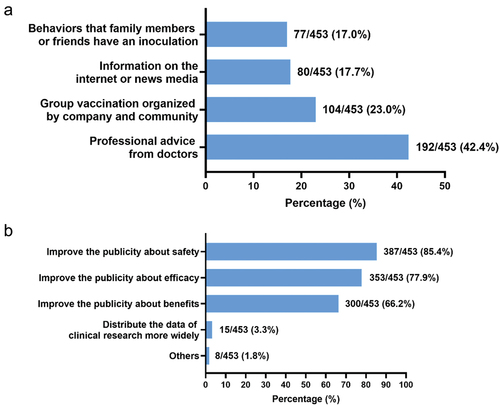

We enquired about the variables that have the greatest influence on booster vaccination intentions in an effort to identify approaches to boost vaccination intentions (). As a consequence, 42.4% of participants reported that their desire to receive a booster shot was most influenced by doctor’s professional advice. According to 23.0% of respondents, the group vaccination organized by their employer and community had the greatest impact on their willingness. While 17.7% and 17.0% of participants each replied that they were most influenced by the information obtained via the internet or new media, or by the behaviors of their family members or friends who got a booster, respectively.

Figure 2. External influences related to COVID-19 booster vaccination. (a) The most influential variables on the willingness to receive booster shots. (b) Suggestions for increasing intention to receive booster vaccinations from respondents.

Additionally, suggestions for encouraging higher boosting vaccination intentions were requested (). Most respondents (85.4%) emphasized the need for improved safety information dissemination for hypertensive patients. They also recommended enhancing publicity on the efficacy and benefits of boosters (77.9% and 66.2%, respectively) to increase vaccine uptake among hypertensive individuals.

Willingness to pay

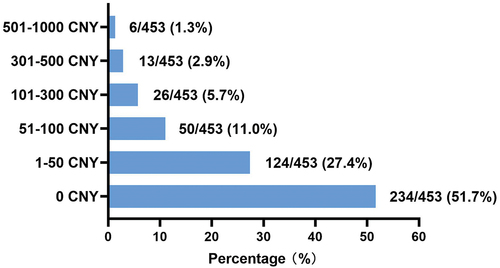

Out of the 453 respondents, 51.7% reported they would refuse to pay for COVID-19 boosters if SARS-CoV-2 persists in coexistence with humans, and the government ceases to provide free COVID-19 vaccinations (). Approximately 27.4%, 11.0%, 5.7%, and 4.2% of respondents were willing to pay 1–50 CNY, 51–100 CNY, 101–300 CNY, and 300–1000 CNY per dose, respectively. None chose to pay more than 1000 CNY. When considering all respondents, the mean willingness-to-pay (WTP) was 12.43 CNY. Among the 219 respondents willing to pay, the mean and median WTP values for a booster were 53.17 CNY and 28.31 CNY, respectively.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study explored the willingness of hypertensive patients in Beijing, Zhengzhou, and Xi’an, China, to receive booster shots or annual vaccinations. The findings address a knowledge gap in public understanding of vaccination among hypertensive patients and provide recommendations for promoting COVID-19 vaccines. In this population, 72.2% were willing to receive a one-dose booster, while 59.4% were willing to consider annual vaccination in the context of long-term COVID-19 coexistence. As COVID-19 continues to coexist with humans and vaccine preventative techniques advance, it remains essential to encourage immunization among hypertensive populations.

According to the COVID-19 vaccination data released by the China CDC, the full-course vaccination coverage rate remained stable at 90.3% in August 2022 and 90.6% in April 2023.Citation40 By April 20, 2023, 64.8% of the fully vaccinated population had received a booster shot.Citation40 Among them, some of the population has not gotten the booster shot because they have not yet reached the time for the booster shot, and some are still hesitant to receive the booster. In this study, a rate of 72.2% of participants indicated being willing to receive a booster. Among fully vaccinated participants, the willingness rate to receive a booster was 68.4% (158/231), which aligns with the data from China CDC. These findings have practical implications for addressing vaccine hesitancy and improving the willingness of hypertensive patients to receive booster shots.

The study identified two primary factors influencing Chinese hypertensive patients’ willingness to receive booster or annual COVID-19 vaccinations: working status and severity of hypertensive disease. Those who were working were more likely to take a booster or receive booster shots regularly. Secondly, the willingness of a dose of booster was associated with the severity of hypertensive disease. The probability of receiving booster shots was higher in people that took no or less antihypertensive medication, with less hypertension-related comorbidities, and did not have any other chronic diseases. This implies that people with hypertension who have poorer health are more reluctant to receive booster shots, which is in line with another study that found people who thought their physical condition was very good or good were more likely to be vaccinated than those who thought they were in fair or poor health.Citation41

The HBM model served as the theoretical framework in this study, providing a comprehensive structure to explain how individuals perceive health threats and engage in health-promoting behaviors.Citation27 Applying the HBM model, we explored how hypertensive patients’ perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, self-efficacy, and cues to action influenced their willingness to receive a booster shot or annual vaccination. We found that respondents with higher perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived self-efficacy, as well as lower perceived barriers were more willing to receive booster shots. These findings were consistent with several previous studies.Citation42–46 Therefore, these results highlight the importance of focusing public health interventions on enhancing beliefs about vaccine safety and efficacy, and lowering perceived side effects among hypertensive individuals, particularly those with poor health who may be more cautious about vaccination.

In terms of vaccine promotion, respondents reported that medical professional advice had the most significant impact on their willingness to receive boosters, followed by group vaccination organized by employers and communities. Research indicates that hospital care team perceive unvaccinated patients as selfish, less mature and less satisfying to care for, and the relationship with them is more difficult.Citation47 This may lead to negative feedback conditioning, with patients with vaccine hesitancy need advice from healthcare professionals to encourage vaccination, while vaccine hesitancy negatively affects the doctor-patient relationship, resulting in lower chances of getting medical professional advice. Thus, this raises awareness of this important issue that appropriate interventions and more expert outreach activities should be organized to disseminate information about booster vaccinations to hypertensive populations, especially those patients with vaccine hesitancy.

As the Chinese government has been providing free vaccines, 51.7% of respondents in this study expressed reluctance to receive self-pay vaccines. Given the possibility that vaccines won’t always be provided without cost in the future, our study showed that for the hypertensive population who were willing to pay, the mean and median WTP value for a dose of booster were 53.17 CNY and 28.31 CNY, respectively. These costs were lower than the 118.62 CNY and 60 CNY reported for the general population.Citation48 This may be due to the cohort in our study is people with hypertension, who were older, and had a higher disease burden.

The utilization of the validated questionnaire ensures the reproducibility of our results, enabling exploring the perceptions of different populations on many aspects related to COVID-19 vaccination, and enhancing the overall understanding of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Several studies reported that the general population may have an alteration in blood pressure values after receiving mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines,Citation49–51 raising concerns not only in hypertensive populations but also among healthcare populations about the safety of vaccination and the potential medical support. Therefore, further surveys of healthcare professionals could be conducted to provide a comprehensive understanding of the issues that may be faced in advancing COVID-19 booster vaccination process.

This study also has some limitations, including its cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inference, and potential selection bias due to geographic sampling and a predominantly urban participant pool. Additionally, the study only reflects vaccination intentions during the data collection period and may not account for policy changes or factors impacting hypertensive patients infected with COVID-19 after the study period.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that Chinese hypertensive patients had a 72.2% willingness rate to receive a booster vaccine and a 59.4% willingness rate for annual vaccination. The primary factors affecting willingness were health and employment status. Increased efforts are needed to enhance perceived severity, benefits, and self-efficacy, while reducing perceived barriers, to improve COVID-19 booster acceptance. Engaging doctors in promoting booster vaccinations for hypertensive patients is crucial, given their high level of trust in medical professionals.

Author contributions

Lunan Wang, Ying Yan conceived the study. Ying Yan, Junjie Xu, Yuanfeng Gao designed the questionnaire. Qingyuan Chen, Qinggang Song collected the data. Le Chang, Huimin Ji, Huizhen Sun searched, sorted, and interpreted the relevant literature. Ying Yan, Abudulimutailipu·Nuermaimaiti analyzed the data. Ying Yan, Abudulimutailipu·Nuermaimaiti, Yingzi Xiao drafted the paper. Lunan Wang, Qinggang Song, Yuanfeng Gao, and Junjie Xu revised the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Revised Supplementary table R2.docx

Download MS Word (37.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants for their cooperation and support. We would like to thank Dr. Ying Yan’s mother, Mrs. Duanyang Chen for her support during the questionnaire collection process. We would like to thank Zhengzhou Jinshui District Jiujiu social work service center for their work in collecting the questionnaires.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2283315.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Olsen MH, Angell SY, Asma S, Boutouyrie P, Burger D, Chirinos JA, Damasceno A, Delles C, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P, Hering D, et al. A call to action and a lifecourse strategy to address the global burden of raised blood pressure on current and future generations: the Lancet commission on hypertension. Lancet. 2016;388(10060):2665–13. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31134-5.

- Zhou B, Perel P, Mensah GA, Ezzati M. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(11):785–802. doi:10.1038/s41569-021-00559-8.

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398:957–80. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1.

- Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, Wang X, Hao G, Zhang Z, Shao L, Tian Y, Dong Y, Zheng C, et al. Status of hypertension in China: results from the China hypertension survey, 2012–2015. Circulation. 2018;137(22):2344–56. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032380.

- Zhang M, Wu J, Zhang X, Hu CH, Zhao ZP, Li C, Huang ZJ, Zhou MG, Wang LM. Prevalence and control of hypertension in adults in China, 2018. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2021;42:1780–9. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20210508-00379.

- Chenchula S, Vidyasagar K, Pathan S, Sharma S, Chavan MR, Bhagavathula AS, Padmavathi R, Manjula M, Chhabra M, Gupta R, et al. Global prevalence and effect of comorbidities and smoking status on severity and mortality of COVID-19 in association with age and gender: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):6415. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-33314-9.

- Li X, Xu S, Yu M, Wang K, Tao Y, Zhou Y, Shi J, Zhou M, Wu B, Yang Z, et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(1):110–18. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006.

- Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, Huang H, Zhang L, Zhou X, Du C, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934–43. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994.

- Chen J, Liu Y, Qin J, Ruan C, Zeng X, Xu A, Yang R, Li J, Cai H, Zhang Z. Hypertension as an independent risk factor for severity and mortality in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study. Postgrad Med J. 2022;98(1161):515–22. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-140674.

- Nashiry A, Sarmin Sumi S, Islam S, Quinn JMW, Moni MA. Bioinformatics and system biology approach to identify the influences of COVID-19 on cardiovascular and hypertensive comorbidities. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(2):1387–401. doi:10.1093/bib/bbaa426.

- Pranata R, Lim MA, Huang I, Raharjo SB, Lukito AA. Hypertension is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2020;21(2):1470320320926899. doi:10.1177/1470320320926899.

- Li M, Wang H, Tian L, Pang Z, Yang Q, Huang T, Fan J, Song L, Tong Y, Fan H. COVID-19 vaccine development: milestones, lessons and prospects. Sig Transduction Targeted Ther. 2022;7:146. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-00996-y.

- WHO. COVID-19 vaccine tracker and landscape [Internet]. [accessed 2023 Apr 25]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines.

- Wang G, Yao Y, Wang Y, Gong J, Meng Q, Wang H, Wang W, Chen X, Zhao Y. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccination status and hesitancy among older adults in China. Nat Med. 2023;29(3):623–31. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02241-7.

- China CDC. COVID-19 situation reports on February 15, 2023. [Internet]. [accessed 2023 Feb 20]. https://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/zl/szkb_11803/jszl_13141/202302/t20230215_263756.html.

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Issues about COVID-19 booster vaccination [Internet]. [accessed 2023 Apr 28]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/s7847/202111/67a59e40580d4b4687b3ed738333f6a9.shtml.

- Ying C-Q, Lin X-Q, Lv L, Chen Y, Jiang J-J, Zhang Y, Tung T-H, Zhu J-S. Intentions of patients with hypertension to receive a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional survey in Taizhou, China. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(10):1635. doi:10.3390/vaccines10101635.

- Tung T-H, Lin X-Q, Chen Y, Zhang M-X, Zhu J-S. Willingness to receive a booster dose of inactivated coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine in Taizhou, China. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022;21(2):261–7. doi:10.1080/14760584.2022.2016401.

- Wang X, Liu L, Pei M, Li X, Li N. Willingness of the general public to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster - China, April-May 2021. China CDC Wkly. 2022;4:66–70. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2022.013.

- The joint prevention and control mechanism of the State Council. second dose of SARS-CoV-2 booster vaccination implementation program [Internet]. [accessed 2023 Feb 20]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-12/14/content_5731899.htm.

- The US FDA. Vaccines and related biological products advisory Committee January 26, 2023 meeting briefing document- FDA | FDA [Internet]. [accessed 2023 Apr 28]. https://www.fda.gov/media/164699/download.

- Couzin-Frankel J. New COVID-19 vaccine strategy would mimic flu’s annual shots. Science. 2023;379(6631):425–6. doi:10.1126/science.adg9446.

- Townsend JP, Hassler HB, Dornburg A. Infection by SARS-CoV-2 with alternate frequencies of mRNA vaccine boosting. J Med Virol. 2023;95(2):e28461. doi:10.1002/jmv.28461.

- The US FDA. Updated COVID-19 vaccines for use in the United States beginning in fall 2023. FDA [Internet]; 2023 [accessed 2023 Oct 16]. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/updated-covid-19-vaccines-use-united-states-beginning-fall-2023.

- MacDonald NE, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Razai MS, Chaudhry UAR, Doerholt K, Bauld L, Majeed A. Covid-19 vaccination hesitancy. BMJ. 2021;373. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1138.

- Carico R, Sheppard J, Thomas CB. Community pharmacists and communication in the time of COVID-19: applying the health belief model. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17:1984–7. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.017.

- Wang H, Huang Y-M, Su X-Y, Xiao W-J, Si M-Y, Wang W-J, Gu X-F, Ma L, Li L, Zhang S-K, et al. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: a multicenter national survey among medical care workers in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(5):2076523. doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2076523.

- Wong LP, Alias H, Wong P-F, Lee HY, AbuBakar S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(9):2204–14. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1790279.

- Limbu YB, Gautam RK, Pham L. The health belief model applied to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a systematic review. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(6):973. doi:10.3390/vaccines10060973.

- Zampetakis LA, Melas C. The health belief model predicts vaccination intentions against COVID-19: a survey experiment approach. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2021;13:469–84. doi:10.1111/aphw.12262.

- Zhou HJ, Pan L, Shi H, Luo JW, Wang P, Porter HK, Bi Y, Li M. Willingness to pay for and willingness to vaccinate with the COVID-19 vaccine booster dose in China. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1013485. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1013485.

- Wang J, Lyu Y, Zhang H, Jing R, Lai X, Feng H, Knoll MD, Fang H. Willingness to pay and financing preferences for COVID-19 vaccination in China. Vaccine. 2021;39(14):1968–76. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.060.

- Bai X, Chen L, Liu X, Tong Y, Wang L, Zhou M, Li Y, Hu G. Adult hepatitis B virus vaccination coverage in China from 2011 to 2021: a systematic review. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(6):900. doi:10.3390/vaccines10060900.

- Hou Z, Chang Null J, Yue D, Fang H, Meng Q, Zhang Y. Determinants of willingness to pay for self-paid vaccines in China. Vaccine. 2014;32(35):4471–7. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.047.

- China’s NHSA. National healthcare security administration: costs of routine COVID-19 nucleic acid tests born by the local governments [Internet]. [accessed 2023 Oct 17]. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-05/26/content_5692466.html.

- Tung T-H, Lin X-Q, Chen Y, Zhang M-X, Zhu J-S. Willingness-to-pay for a booster dose of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in Taizhou, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18:2099210. doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2099210.

- Sj P, Yp Y, Mx Z, Th T. Willingness to pay for booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers in Taizhou,China. Hum Vaccines Immunother [Internet]. 2022 [accessed 2023 Oct 17];18. doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2063629.

- 2018 Chinese guidelines for prevention and treatment of hypertension—a report of the revision Committee of Chinese guidelines for prevention and treatment of hypertension. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2019;16:182–241.

- China CDC. COVID-19 situation reports on April 22, 2023. [Internet]. [accessed 2023 Apr 26]. https://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/zl/szkb_11803/jszl_13141/202304/t20230422_265534.html.

- Jiang N, Yang C, Yu W, Luo L, Tan X, Yang L. Changes of COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, practices and vaccination willingness among residents in Jinan, China. Front Public Health. 2022;10:917364. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.917364.

- Wang J, Yuan B, Lu X, Liu X, Li L, Geng S, Zhang H, Lai X, Lyu Y, Feng H, et al. Willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine among the elderly and the chronic disease population in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(12):4873–88. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2009290.

- Nehal KR, Steendam LM, Campos Ponce M, van der Hoeven M, Smit GSA. Worldwide vaccination willingness for COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:1071. doi:10.3390/vaccines9101071.

- Yin D, Chen H, Deng Z, Yuan Y, Chen M, Cao H, Zhou X, Luo J, Zhang W, Gu Z, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among industrial workers in the post-vaccination era: a large-scale cross-sectional survey in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(12):5069–75. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1989912.

- Ramot S, Tal O. Attitudes of healthcare workers in Israel towards the fourth dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11(2):385. doi:10.3390/vaccines11020385.

- Duan L, Wang Y, Dong H, Song C, Zheng J, Li J, Li M, Wang J, Yang J, Xu J. The COVID-19 vaccination behavior and correlates in diabetic patients: a health belief model theory-based cross-sectional study in China, 2021. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(5):659. doi:10.3390/vaccines10050659.

- Caspi I, Freund O, Pines O, Elkana O, Ablin JN, Bornstein G. Effect of patient COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy on hospital care team perceptions. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11(4):821–9. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v11.i4.821.

- Lai X, Zhu H, Wang J, Huang Y, Jing R, Lyu Y, Zhang H, Feng H, Guo J, Fang H. Public perceptions and acceptance of COVID-19 booster vaccination in China: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(12):1461. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121461.

- Simonini M, Scarale MG, Tunesi F, Manunta P, Lanzani C, Di Serio PC, Moro DM, Multidisciplinary Epidemiological Research Team Study Group. COVID-19 vaccines effect on blood pressure. Eur J Intern Med. 2022;105:109–10. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2022.08.027.

- Zappa M, Verdecchia P, Spanevello A, Visca D, Angeli F. Blood pressure increase after Pfizer/BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;90:111–13. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2021.06.013.

- Meylan S, Livio F, Foerster M, Genoud PJ, Marguet F, Wuerzner G. CHUV COVID vaccination center. Stage III hypertension in patients after mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Hypertension. 2021;77(6):e56–7. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17316.