ABSTRACT

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines have a protective effect on individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), preventing them from developing severe illnesses and reducing the risk of hospitalization and mortality. However, the coverage rate of COVID-19 vaccination among this population is not satisfactory, which is associated with their lack of awareness of and negative attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination, that is, vaccine hesitancy. We reviewed recent literatures on the vaccination status of COPD patients and vaccine hesitancy, described the factors related to vaccine hesitancy among COPD patients, and proposed strategies to improve the vaccine coverage, such as providing accurate and consistent vaccine information to the public, patient health education program, improving self-management capabilities, easy access to vaccination service, etc., which can hopefully help to improve patients’ ability to cope with SARS-CoV-2 infection and reduce the COVID-19 related mortality.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death worldwideCitation1 and leads to substantial economic and social burdens.Citation2 During the pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), patients with COPD have been shown to be at higher risk of developing severe illness and mortality once they are infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).Citation3,Citation4 COVID-19 vaccination can protect the vaccinated individuals against SARS-CoV-2 infection,Citation5–7 and therefore the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommends that patients with COPD should receive COVID-19 vaccination in line with national recommendations.Citation1 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that global COVID-19 vaccination should cover ≥70% of the national population as a target for further disease reduction and protection against future risks. By October 17, 2022, 4.98 billion people have been vaccinated with at least one dose of COVID-19, covering 64% of the eligible vaccination population.Citation8 However, a study during June 1 to July 30 of 2021 showed that the actual coverage of COVID-19 vaccines in the individuals with COPD was approximately 40%, much lower than the global vaccination target.Citation9 At present, only a small number of studies have focused on the COVID-19 vaccination among patients with COPD, whose awareness and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination are largely unexplored. Awareness of and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination in this population may vary and depend on different regions, races, and religious beliefs. In this review, we will discuss the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination in COPD patients, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, awareness and attitude toward vaccination, and strategies to address this issue among individuals with COPD.

The evidence of protective roles of COVID-19 vaccination for COPD

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor on the surface of small airway epithelia is the key binding site of SARS-CoV-2. Smokers and patients with COPD have increased expression of the enzyme ACE-2 in their airways.Citation10 Additionally, most patients with COPD are current-smokers or ex-smokers, in whom the expression of ACE2 receptor is upregulated.Citation11 These data may explain the higher risk of severe illness and mortality among COPD patients when they are infected. COVID-19 vaccination has been proven to protect this population against SARS-Cov-2 infection or developing severe disease. In the vaccinated COPD individuals, anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike IgA and IgG levels in plasma were higher compared to those unvaccinated. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike IgG levels in sputum were also higher, although sputum anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgA levels were not significantly increased. Vaccinated COPD individuals showed higher spike-protein induced interferon-γ (IFN-γ) levels in plasma.Citation12 The airway and blood immune responses to COVID-19 vaccination, including both cellular and humoral immunity, were similar between COPD patients and healthy subjects.Citation12

A large-scale, multicenter study conducted in the United States in the first half of 2021 demonstrated that mRNA-based vaccination reduced the risk of hospitalization and emergency department and urgent care visits due to SARS-CoV-2 infection by 90% among patients with chronic respiratory diseases fully vaccinated by two doses.Citation13 Even among patients who were at least 85 years old, this effectiveness was still over 80%.Citation13 For the patients with COPD, both BNT162b2 and CoronaVac vaccines can effectively prevent them from hospitalization and respiratory failure due to SARS-CoV-2 infection.Citation14 Although a report from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) showed that COPD was the most common comorbidity in vaccination-related deaths, alongside hypertension, dementia, diabetes, and heart failure, it should be noted that the rate of vaccination-related deaths was extremely low (53.4/1,000,000) and most of the deaths occurred in long-term care facility residents.Citation15 Therefore, this report actually proved the benefit of COVID-19 vaccination, benefits outweighing potential risks in older frail populations.Citation15

Awareness and attitudes around COVID-19 vaccination and vaccine hesitancy

Vaccine hesitancy is a term defined as “a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccinations services” by the World Health Organization. The common causes of vaccine hesitancy include distrust of the effectiveness and safety of vaccines, frailty and comorbidities, not thinking vaccination necessary, and lack of knowledge on vaccines.Citation16–19 A systemic-review identified the barriers and facilitators of COVID-19 vaccine uptake, based on 5As taxonomy (access, awareness, affordability, acceptance, activation), among the migrant populations and health-care professionals working with them in Europe.Citation20 The barriers to acceptance of vaccines were summarized as the following factors: concerns about the safety and side-effects, cultural, religious or social factors, distrust of health system or authorities, misinformation or lack of positive information, low perceived importance and effectiveness of vaccination and low perceived risk of vaccine-preventable diseases, and no physician-recommendations. Lack of awareness of vaccines was noted to be another barrier to vaccination uptake, including lack of knowledge about disease or need for vaccination, entitlement to vaccination, personal medical or vaccination history, misinformation or lack of information about the vaccines and its availability.Citation20 In another review, health literacy understandability and clarity of information regarding vaccines, trust or mistrust of authoritative institutions and healthcare institutions, personal judgments around risk versus benefit, personal or group customs or ideologies were identified to be the most common determinants relevant to COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy.Citation21 In addition, having comorbid chronic diseases was also a reason for vaccination hesitancy. The intention to receive COVID-19 vaccination was found to be low in those with various chronic diseases.Citation22 The severity of COPD was associated with the coverage rate of COVID-19 vaccination among individuals with COPD. A recent study showed that unvaccinated patients with COPD had heavier symptom burdens and more severe dyspnea.Citation23 In our study of COPD patients, most of the unvaccinated individuals did not intend to receive COVID-19 vaccination. Nearly a half of them thought that COVID-19 vaccines were not appropriate for patients with COPD, and about 30% of them were concerned about potential side-effects.Citation9 Although recommendations from healthcare professionals were positive, COVID-19 vaccination was recommended by clinicians only in a small proportion of patients with COPD.Citation9 However, during the study period, there was no enough evidence regarding the effectiveness and safety of COVID-19 vaccination in patients with COPD, which might hamper clinicians’ recommendations on COVID-19 vaccination. Most recently, the safety of COVID-19 vaccines has been fully proved. Data from VAERS system showed that among nearly 300 million RNA vaccine doses (BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273) administered in the United States between December 14, 2020 and June 14, 2021, only 340, 522 reports were received regarding potential adverse events after both dose one and dose two, and over 90% of these reports were non-serious, with very rare vaccination-related deaths being reported.Citation24 After that, the safety of COVID-19 vaccine booster dose was also proved in adult populations and the local and systemic reactions were rare, with more than 90% of the reported side-effects non-serious.Citation25,Citation26 As the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines is widely confirmed, it is believed that COVID-19 vaccination will be more widely recommended by the clinicians and other healthcare workers and the acceptance and uptake of COVID-19 vaccines will continue to be improved over time. However, the evidence regarding coverage rate of COVID-19 vaccines among the COPD population is still limited and relevant studies were only undertaken in small samples.Citation9,Citation23 Moreover, the proportions of fully vaccinated population are substantially different among different countries and regions. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct extensive surveys in order to thoroughly investigate the vaccine uptake rate and hesitancy in individuals with COPD.

An individual’s hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination is also influenced by his/her awareness of and attitudes to other vaccines. Annual influenza vaccination is recommended for all COPD patients, and pneumococcal vaccination is recommended for those with COPD aged >65 years, in order to reduce the risk of exacerbation induced by influenza or pneumococcal infection.Citation2 In the individuals receiving influenza vaccination in the 2020–2021 influenza season, the willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination was notably higher than in those not receiving influenza vaccination.Citation27–29 We also found that the uptake rate of COVID-19 vaccination was higher in patients with COPD who had ever received influenza vaccination in the past influenza season or received pneumococcal vaccination in the past year.Citation9 These data indicated that individuals ever vaccinated with other vaccines before showed better adherence to and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines, with less vaccination hesitancy.

Some demographic factors can influence the acceptance of and hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination in COPD patients. Lower education level and income were inversely associated with the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination.Citation30,Citation31 Meanwhile, the risk of developing COPD is higher among the population with relatively lower education levels,Citation32 which can partly explain the low coverage rate of COVID-19 vaccination in individuals with COPD. Other factors, such as age, gender, religious belief, residence in rural or remote area, and having children at home were also associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy,Citation31,Citation33–36 although these factors have not yet been assessed in the COPD population.

Strategies to overcome hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination

Although the coverage of COVID-19 vaccines and the intention to receive COVID-19 vaccination are relatively high in developed countries,Citation37 the coverage in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is still unsatisfactory, with increasing vaccination hesitancy or resistance.Citation38 For example, a recent study carried out in Hungary showed that the coverage rate of the first dose of COVID-19 vaccination among COPD patients was 88.62%, whereas the second vaccine dose was up to 86.57%,Citation23 which was much higher than the vaccination coverage in most low- and middle-income countries. For LMICs, due to a general lack of vaccine production capacity and related resources, timely access to COVID-19 vaccination is limited, resulting in universally low vaccination rates, with 45 countries having vaccination rates less than 10% of their population and 20 countries not having enough doses to vaccinate their elderly people and healthcare workers.Citation39 The COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) facility, founded in April 2020, was committed to providing equitable vaccine access for people in LMICs, but the vaccination rates were still not satisfactory in these countries until 2022.

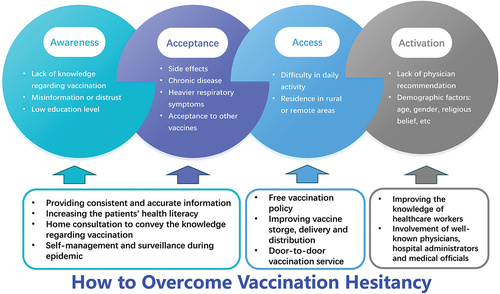

The majority of patients with COPD in the world live in LMICs,Citation40 resulting in substantial socioeconomic burdens. For individuals with COPD, COVID-19 vaccination can offer protection against COVID-19 related exacerbation and mortality.Citation23 This vulnerable population should be given priority to get COVID-19 vaccination, especially in LMICs. Effective measures can reduce vaccine hesitancy and increase vaccine coverage in this population ().

Figure 1. The four contributing factors for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among COPD patients and the corresponding solutions.

Patient education

In the past 3 years of COVID-19 pandemic, individuals with COPD and their relatives have gradually become aware of the importance of COVID-19 vaccination and have a more and more positive attitude toward it. They would gradually recognize the potential benefits of vaccination in reducing the risk of severe illness and complications from COVID-19. However, lack of awareness of vaccine effectiveness and safety is still a major barrier for COVID-19 vaccination acceptance and contributes to the concerns or hesitations about COVID-19 vaccination. Besides concerns about side-effect, various rumors and conspiracy theories regarding COVID-19 vaccines due to online misinformation continue to undermine the trust in vaccination around the world.Citation41 Public institutions, official media, and healthcare professionals should provide consistent and accurate information regarding COVID-19 vaccines to address the concerns and hesitations,Citation42 especially the need and safety among the elderly population with chronic respiratory diseases. Additionally, increasing people’s health literacy and emphasizing the importance of protecting the role of vaccines against COVID-19 could improve vaccination hesitancy and enhance the willingness to be vaccinated. Self-management by patients with COPD is critical during COVID-19 pandemic, such as monitoring their own health status and respiratory symptoms, maintaining long-term treatment, and understanding the access to necessary healthcare services, as well as vaccination recommendations for patients with COPD.Citation2 The Chinese government has made efforts to effectively improve vaccination coverage in various ways. In November 2022, a government document entitled “A working program to enhance COVID-19 vaccination coverage in older people” was issued, which aimed to increase in COVID-19 vaccination coverage among those aged over 80 years and continue to increase COVID-19 vaccination coverage among those aged 60–79 years. In addition, a large amount of news via the mass media every day to educate the elderly on COVID-19 prevention and control measures and staffs or volunteers in various communities entered residents’ homes to convey the knowledge relevant to COVID-19 vaccination and urge elderly people with chronic comorbidities to complete vaccination, so as to improve their awareness and confidence in the vaccine and avoid the spread of false information.Citation43

Positive medical advice from healthcare workers

The role of medical advice in promoting vaccination campaign has been highlighted in previous studies.Citation44–47 The level of trust in healthcare professionals among the general population is strongly associated with the willingness and uptake rate of COVID-19 vaccination.Citation48 Improving the knowledge of healthcare workers in hospitals and primary medical institutions regarding the function, benefit, and the need of COVID-19 vaccination for those with COPD may become an important strategy for increasing vaccination acceptance and coverage. In other words, the awareness and attitudes of the healthcare workers toward the vaccines can often have a powerful influence on vaccine acceptance of their patients and the public. Israel has a high vaccination coverage compared to most countries worldwide, with only 7.3% of people aged 60–69 years unvaccinated and 0.85% of people aged 70–79 years unvaccinated. Well-known physicians, hospital administrators, and medical officials in Israel participated in the vaccination campaign and shared their experience, knowledge, and positive emotions and stories with healthcare workers on getting vaccinated, targeting to strengthen and deepen trust and confidence to COVID-19 vaccination.Citation49 Therefore, we suggest that healthcare workers are not only the providers of vaccination advice but also the masters of vaccination knowledge to promote vaccination campaigns in communities.

Free vaccination policy and feasible access to vaccination

Affordability and accessibility of vaccines are important determinants of vaccine coverage.Citation20 For example, a subsidy policy providing free influenza vaccination to residents aging ≥60 years has been implemented in mainland China since 2007.Citation50 In the early 2021, inactivated COVID-19 vaccines started to be widely used in adult population in mainland China for free and this policy has lasted till now.Citation9 It is no doubt that cost offsetting including free vaccination policy and insurance cover is facilitators of acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination, while various direct or indirect costs for vaccines and completing priorities are barriers to prompting vaccine campaigns.Citation20 Additionally, providing easy access to vaccination services can help increase the willingness to vaccinate,Citation21 especially among those with COPD who are mostly elderly and have difficulty in daily activity. Improving vaccine delivery and logistics can facilitate the access to COVID-19 vaccination for rural or remote residents. Patients with COPD are often elderly and have difficulty moving, resulting in difficulty getting vaccinated in hospitals or community healthcare institutions. Healthcare workers can complete vaccination for these patients and monitor the adverse effects of vaccine at home. For those patients living in rural or remote areas, special attention should be paid, due to their poor outcomes and medical conditions. The methods of vaccine storage, delivery, and distribution need to be further optimized to help these patients get vaccinated more conveniently, which can improve the willingness and acceptance of vaccination in these areas.

Mandatory vaccination

Mandatory vaccination appears to be useful for enhancing vaccine coverage, but this has been controversial. Mandatory influenza vaccination among healthcare workers can effectively increase the influenza vaccine uptake,Citation51 but this is more due to the moral obligation of healthcare workers and the known efficacy and safety of influenza vaccine. However, this policy appears to be unfeasible and undesirable for these novel, provisionally approved vaccines. In addition, mandating vaccination cannot actually address the problem of vaccination hesitancy or resistance. Mandatory vaccination may even have a negative impact on public confidence and trust in COVID-19 vaccination. In the context of social morality, increasing the vaccine uptake can form a herd immunity barrier as soon as possible and protect high-risk individuals in the population. However, it seems to be difficult to balance social morality, community health, and individual freedom,Citation52 even though the efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines have been proven during the past 3 years. Therefore, the World Health Organization suggests that mandating vaccines should be a last resort for enhancing vaccine uptake, which has received general agreement.

For patients with other chronic diseases

Similar to patients with COPD, patients with other chronic diseases (such as heart failure, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, etc.) can also benefit from COVID-19 vaccination, and the safety of the vaccines has also been confirmed in these patients, in whom the recommendations and perspectives of this review can also be used to improve vaccine acceptance and vaccination uptake. For example, awareness of vaccines can be raised through patient education programs; healthcare workers can actively encourage the elderly with chronic diseases to get vaccinated timely; and for those with difficulty in daily mobility, healthcare workers or volunteers can provide door-to-door vaccination services if possible. In addition, it is important to increase access to vaccines for individuals with chronic diseases in rural or remote areas.

Conclusion and future prospects

During the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals with COPD are susceptible to severe illness and increased mortality once they are infected by SARS-CoV-2. COVID-19 vaccination can induce airway and systemic immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 virus, which are similar between individuals with COPD and healthy controls. Clinical trials have demonstrated the protective role of vaccines among patients with chronic respiratory diseases including COPD. Therefore, GOLD guidelines recommend that COVID-19 vaccines be used in patients with COPD in line with national recommendations. However, the actual coverage of COVID-19 vaccination in individuals with COPD is relatively low. Similar to the general population, hesitancy to COVID-19 vaccination is a common issue among those with COPD (). A lack of knowledge regarding the effectiveness and safety and the need of COVID-19 vaccination, concerns about the side-effect, COPD per se, insufficient recommendation from healthcare workers, and lower education levels are the common causes of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy. Previous experiences with influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are able to facilitate COVID-19 vaccination and minimize vaccine hesitancy. Strategies to overcome COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among COPD patients, healthcare workers, public institutions, and government sectors should be implemented ( and ), including consistent and accurate messaging to individuals with COPD and patient education programs regarding COVID-19 vaccines in terms of benefits, potential side effects, and other concerns. The role of healthcare workers in promoting vaccination campaign should be highlighted. They can convey accurate and positive information and advice regarding COVID-19 vaccination and provide vaccination services at homes, especially for the elderly who have difficulty in outdoor activity. Additionally, free vaccination policy and easy access to COVID-19 vaccination service are helpful for overcoming vaccination hesitancy, especially for the large population of low-income patients with COPD living in remote areas. In the context of COVID-19 epidemic, the COVID-19 vaccination coverage rate in individuals with various chronic airway diseases, the protective effect and safety of different types of vaccines, and whether annual regular vaccination can benefit this population are needed to be further addressed in the future.

Table 1. Vaccine hesitancy among COPD patients and strategies to address it.

Author’s contribution

Ying Liang and Yongchang Sun contributed equally to the conception and design, the drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content; and the final approval of the version to be published; and that all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Organization WH. Evidence-informed policy network: EVIPnet in action; [ accessed 2021 Nov 10]. http://www.who.int/evidence.

- Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD) 2021 report; [accessed 2021 Jan 15]. http://www.goldcopd.org/.

- Alqahtani JS, Oyelade T, Aldhahir AM, Alghamdi SM, Almehmadi M, Alqahtani AS, Quaderi S, Mandal S, Hurst JR. Prevalence, severity and mortality associated with COPD and smoking in patients with COVID-19: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0233147. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233147.

- Guan WJ, Liang WH, Zhao Y, Liang H-R, Chen Z-S, Li Y-M, Liu X-Q, Chen R-C, Tang C-L, Wang T, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5):2000547. doi:10.1183/13993003.00547-2020.

- Wu Z, Hu Y, Xu M, Chen Z, Yang W, Jiang Z, Li M, Jin H, Cui G, Chen P, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac) in healthy adults aged 60 years and older: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(6):803–7. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30987-7.

- Logunov DY, Dolzhikova IV, Shcheblyakov DV, Tukhvatulin AI, Zubkova OV, Dzharullaeva AS, Kovyrshina AV, Lubenets NL, Grousova DM, Erokhova AS, Safety and efficacy of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine: an interim analysis of a randomised controlled phase 3 trial in Russia. Lancet. 2021;397(10275):671–81. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00234-8.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, Diemert D, Spector SA, Rouphael N, Creech CB, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–16. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389.

- Adu P, Poopola T, Medvedev ON, Collings S, Mbinta J, Aspin C, Simpson CR. Implications for COVID-19 vaccine uptake: a systematic review. J Infect Public Health. 2023;16(3):441–66. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2023.01.020.

- Song Z, Liu X, Xiang P, Lin Y, Dai L, Guo Y, Liao J, Chen Y, Liang Y, Sun Y, et al. The Current status of vaccine uptake and the impact of COVID-19 on intention to vaccination in patients with COPD in Beijing. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:3337–46. doi:10.2147/COPD.S340730.

- Leung JM, Yang CX, Tam A, Shaipanich T, Hackett T-L, Singhera GK, Dorscheid DR, Sin DD. ACE-2 expression in the small airway epithelia of smokers and COPD patients: implications for COVID-19. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5):2000688. doi:10.1183/13993003.00688-2020.

- Brake SJ, Barnsley K, Lu W, McAlinden KD, Eapen MS, Sohal SS. Smoking upregulates angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 receptor: a potential adhesion site for novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19). J Clin Med. 2020;9(3): doi:10.3390/jcm9030841.

- Southworth T, Jackson N, Singh D. Airway immune responses to COVID-19 vaccination in COPD patients and healthy subjects. Eur Respir J. 2022;60(2): doi:10.1183/13993003.00497-2022.

- Thompson MG, Stenehjem E, Grannis S, Ball SW, Naleway AL, Ong TC, DeSilva MB, Natarajan K, Bozio CH, Lewis N, et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines in ambulatory and inpatient care settings. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(15):1355–71. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2110362.

- Kwok WC, Leung S, Tam T, Ho JCM, Lam DCL, Ip MSM, Ho PL. Efficacy of mRNA and inactivated whole virus vaccines against COVID-19 in patients with chronic respiratory diseases. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2023;18:47–56. doi:10.2147/COPD.S394101.

- Lv G, Yuan J, Xiong X, Li M. Mortality rate and characteristics of deaths following COVID-19 vaccination. Front Med. 2021;8:670370. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.670370.

- Huang HH, Chen SJ, Chao TF, Liu C-J, Chen T-J, Chou P, Wang F-D. Influenza vaccination and risk of respiratory failure in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a nationwide population-based case-cohort study. J Microbiol, Immunol Infect. 2019;52(1):22–9. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2017.08.014.

- Joseph C, Elgohari S, Nichols T, Verlander N. Influenza vaccine uptake in adults aged 50–64 years: policy and practice in England 2003/2004. Vaccine. 2006;24(11):1786–91. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.10.024.

- Hara M, Sakamoto T, Tanaka K. Influenza vaccine effectiveness among elderly persons living in the community during the 2003–2004 season. Vaccine. 2008;26(50):6477–80. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.035.

- Kwong EW, Lam IO, Chan TM. What factors affect influenza vaccine uptake among community-dwelling older Chinese people in Hong Kong general outpatient clinics. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(7):960–71. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02548.x.

- Crawshaw AF, Farah Y, Deal A, Rustage K, Hayward SE, Carter J, Knights F, Goldsmith LP, Campos-Matos I, Wurie F, et al. Defining the determinants of vaccine uptake and undervaccination in migrant populations in Europe to improve routine and COVID-19 vaccine uptake: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(9):e254–e66. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00066-4.

- Peters M. Addressing vaccine hesitancy and resistance for COVID-19 vaccines. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;131:104241. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104241.

- Adella GA, Abebe K, Atnafu N, Azeze GA, Alene T, Molla S, Ambaw G, Amera T, Yosef A, Eshetu K, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and intention to accept COVID-19 vaccine among patients with chronic diseases in southern Ethiopia: multi-center study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:917925. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.917925.

- Fekete M, Horvath A, Santa B, Tomisa G, Szollosi G, Ungvari Z, Fazekas-Pongor V, Major D, Tarantini S, Varga JT. COVID-19 vaccination coverage in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a cross-sectional study in Hungary. Vaccine. 2023;41(1):193–200. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.11.020.

- Rosenblum HG, Gee J, Liu R, Marquez PL, Zhang B, Strid P, Abara WE, McNeil MM, Myers TR, Hause AM, et al. Safety of mRNA vaccines administered during the initial 6 months of the US COVID-19 vaccination programme: an observational study of reports to the vaccine adverse event reporting system and v-safe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:802–12. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00054-8.

- Hause AM, Baggs J, Marquez P, Myers TR, Su JR, Blanc PG, Gwira Baumblatt JA, Woo EJ, Gee J, Shimabukuro TT, et al. Safety monitoring of COVID-19 vaccine booster doses among adults — United States, September 22, 2021–February 6, 2022. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(7):249–54. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7107e1.

- Munro A, Janani L, Cornelius V, Aley PK, Babbage G, Baxter D, Bula M, Cathie K, Chatterjee K, Dodd K, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of seven COVID-19 vaccines as a third dose (booster) following two doses of ChAdOx1 nCov-19 or BNT162b2 in the UK (COV-BOOST): a blinded, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2021;398:2258–76. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02717-3.

- Belingheri M, Roncalli M, Riva MA, Paladino ME, Teruzzi CM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and reasons for or against adherence among dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152(9):740–6. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2021.04.020.

- Burke PF, Masters D, Massey G. Enablers and barriers to COVID-19 vaccine uptake: an international study of perceptions and intentions. Vaccine. 2021;39(36):5116–28. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.056.

- Alibrahim J, Awad A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the public in Kuwait: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8836. doi:10.3390/ijerph18168836.

- Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, Wiblishauser MJ, Sharma M, Webb FJ. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health. 2021;46:270–7. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x.

- Soares P, Rocha JV, Moniz M, Gama A, Laires PA, Pedro AR, Dias S, Leite A, Nunes C. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(3): doi:10.3390/vaccines9030300.

- Wang C, Xu J, Yang L, Xu Y, Zhang X, Bai C, Kang J, Ran P, Shen H, Wen F, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China (the China pulmonary Health [CPH] study): a national cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2018;391(10131):1706–17. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30841-9.

- Callaghan T, Moghtaderi A, Lueck JA, Hotez P, Strych U, Dor A, Fowler EF, Motta M. Correlates and disparities of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Social Sci Med. 2021;272:113638. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113638.

- Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a survey of U.S. Adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:964–73. doi:10.7326/M20-3569.

- Nguyen TC, Gathecha E, Kauffman R, Wright S, Harris CM. Healthcare distrust among hospitalised black patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Postgrad Med J. 2022;98:539–43. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-140824.

- Walker KK, Head KJ, Owens H, Zimet GD. A qualitative study exploring the relationship between mothers’ vaccine hesitancy and health beliefs with COVID-19 vaccination intention and prevention during the early pandemic months. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:3355–64. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1942713.

- Ohlsen EC, Yankey D, Pezzi C, Kriss JL, Lu PJ, Hung MC, Bernabe M, Kumar GS, Jentes E, Elam-Evans LD, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination coverage, intentions, attitudes, and barriers by race/ethnicity, language of interview, and nativity—national immunization survey adult COVID module, 22 April 2021–29 January 2022. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(Supplement_2):S182–S92. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac508.

- Dubé È, Ward JK, Verger P, MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy, acceptance, and anti-vaccination: trends and future prospects for public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42:175–91. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102240.

- Mobarak AM, Miguel E, Abaluck J, Ahuja A, Alsan M, Banerjee A, Breza E, Chandrasekhar AG, Duflo E, Dzansi J, et al. End COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries. Science. 2022;375(6585):1105–10. doi:10.1126/science.abo4089.

- Adeloye D, Song P, Zhu Y, Campbell H, Sheikh A, Rudan I. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(5):447–58. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00511-7.

- Pertwee E, Simas C, Larson HJ. An epidemic of uncertainty: rumors, conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy. Nat Med. 2022;28:456–9. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01728-z.

- Coustasse A, Kimble C, Maxik K. COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy: a challenge the United States must overcome. J Ambul Care Manage. 2021;44:71–5. doi:10.1097/JAC.0000000000000360.

- Zhu KW. Why is it necessary to improve COVID-19 vaccination coverage in older people? How to improve the vaccination coverage. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(2):2229704. doi:10.1080/21645515.2023.2229704.

- Santos-Sancho JM, Jimenez-Trujillo I, Hernández-Barrera V, López-de Andrés A, Carrasco-Garrido P, Ortega-Molina P, Jiménez-García R. Influenza vaccination coverage and uptake predictors among Spanish adults suffering COPD. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8(7):938–45. doi:10.4161/hv.20204.

- Yeung MP, Lam FL, Coker R. Factors associated with the uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination in adults: a systematic review. J Public Health (Oxf). 2016;38(4):746–53. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdv194.

- Li A, Chan YH, Liew MF, Pandey R, Phua J. Improving influenza vaccination coverage among patients with COPD: a pilot project. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:2527–33. doi:10.2147/COPD.S222524.

- Bazargan M, Wisseh C, Adinkrah E, Ameli H, Santana D, Cobb S, Assari S. Influenza vaccination among underserved African-American older adults. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1–9. doi:10.1155/2020/2160894.

- Chen X, Lee W, Lin F. Infodemic, institutional trust, and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a cross-national survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(13): doi:10.3390/ijerph19138033.

- Ramot S, Tal O. Supporting healthcare workers in vaccination efforts. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(1):2172882. doi:10.1080/21645515.2023.2172882.

- Zhang Y, Muscatello DJ, Wang Q, Yang P, Wu J, MacIntyre CR. Overview of influenza vaccination policy in Beijing, China: current status and future prospects. J Public Health Policy. 2017;38(3):366–79. doi:10.1057/s41271-017-0079-7.

- Schumacher S, Salmanton-García J, Cornely OA, Mellinghoff SC. Increasing influenza vaccination coverage in healthcare workers: a review on campaign strategies and their effect. Infection. 2021;49(3):387–99. doi:10.1007/s15010-020-01555-9.

- Sadique MZ. Individual freedom versus collective responsibility: an economic epidemiology perspective. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2006;3:12. doi:10.1186/1742-7622-3-12.