ABSTRACT

Nigeria has the highest burden of measles worldwide, as measles vaccine uptake remains low. Recently, the second dose of the measles-containing vaccine (MCV2) was introduced as part of the routine immunization (RI) program, and this study examined how it changed the uptake of the measles vaccine and the factors associated with vaccination behavior. The Nigeria Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2021 was used to compare measles vaccination uptake as well as factors associated with vaccination uptake between children before MCV2 introduction (cohort 1) and after the introduction (cohort 2). The overall rate of measles vaccine uptake was higher among cohort 1 (64%–95%) than among cohort 2 (56%–92%) in all zones because of younger age among cohort 2. The dropout from the first to second measles vaccines was similar between the cohorts (around 24%). Higher maternal education levels and higher household wealth levels were both correlated with the vaccine uptake or both cohorts but a positive correlation between the dropout and mother’s education level was observed only among cohort 2, especially in the North West and South West zones. The positive correlation between the dropout and mother’s education level among cohort 2 indicates that the introduction of MCV2 as part of RI might have helped to narrow the disparity in measles vaccine uptake in North West and South West zones. Further study is required to investigate strategies employed to reduce the disparity in these zones to apply nationwide.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Vaccination is one of the most cost effective public health interventions, and it saves millions of lives.Citation1,Citation2 Vaccination against measles has a particularly remarkable history. Prior to the introduction of the measles vaccine in the United States, 3 million lives were affected by measles each year. With the measles vaccine, this number dropped substantially, to less than 100 reported measles cases per year.Citation3 By the year 2000, continuous measles transmission in the United States had been absent for over 12 months, and measles was declared to be eliminated. This was largely due to the introduction of an effective measles vaccine along with a vaccination program.Citation4

The high efficacy of the measles vaccine has also been reported in the context of developing countries. Between 2003 and 2020, measles vaccination coverage improved in Southeast Asia, and the number of deaths due to measles decreased by 97%, or 9.3 million.Citation5 In Africa, an estimated 4.5 million deaths were averted by measles vaccination between 2017 and 2020.Citation6

Despite this, Nigeria has been struggling with a high burden of measles and low vaccine uptake. In 2021, it had over 10,000 recorded cases of measles, making Nigeria the country with the highest number of measles cases in the world.Citation7 The measles vaccination rate has been just over 50% (54% in 2018), which is lower than the rate of 70% among countries in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation8

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic further disrupted the efforts to improve vaccine uptake. Several studies found that the largest dropout rate of vaccination uptake among sub-Saharan African countries was observed in Nigeria.Citation9,Citation10 Amid this unprecedented pandemic, the Nigerian government introduced the second dose of measles-containing vaccine (MCV2) as part of routine immunization (RI). Before the introduction of MCV2, the first dose of the measles-containing vaccine (MCV1) had been part of RI, with children receiving MCV1 at the age of 9 months.Citation11

In addition to the low uptake of MCV1 in Nigeria, vaccination distribution rates have been unequal.Citation12,Citation13 The vaccination rate in the northern region of Nigeria is much lower than in the southern region. MCV1 uptake was 39%–54% in the northern regions but over 70% in all southern regions.Citation8 Given this disparity in vaccine uptake, it is important to examine how the introduction of MCV2 affected the overall uptake of measles vaccination and the difference in vaccine uptake between the first and second measles vaccine (the dropout rate) and the inequities of measles vaccination coverage.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the changes in uptake and dropout rates of measles vaccination and the factors associated with MCV uptake before and after the introduction of MCV2 as part of RI in Nigeria. The main objective of the study was to evaluate how the uptake of the second dose of the measles vaccine improved after its introduction as part of RI and to explore the correlation between the sociodemographic characteristics of children’s caregivers and vaccination behavior toward the second dose of the measles vaccine. We hypothesized that measles vaccination coverage might have improved after the introduction of MCV2 as part of RI, with disadvantaged households reaping the most benefits from the MCV2 program. We also hypothesized that the vaccination coverage of the second dose of measles vaccine improved, particularly among the vulnerable population, due to MCV2 having been introduced as part of a government intervention, as this may have eased certain critical constraints that the vulnerable population would likely have faced in the absence of government intervention. Such constraints might include the financial burdens involved in traveling to health facilities offering the vaccination service, especially MCV2,Citation14 and the direct costs of receiving the vaccination service.Citation15

Methods

Introduction of the second measles vaccine (MCV2)

MCV2 was first introduced in the southern zones of Nigeria in late 2019, and in the northern zones in 2020. The Nigerian federal government introduced MCV2 as part of an RI program that already included MCV1. As part of the current RI program, MCV1 is given to children aged 9 months and MCV2, to children aged 15 to 24 months.

Before MCV2 was introduced as part of RI, the second dose of the measles vaccine was available to children during supplemental immunization activities (SIAs), which focused on a mass measles immunization campaign that occurred every 2 to 4 years.Citation16 The frequency of SIAs differ for different geographic regions.

Whether children qualified for the second dose of the measles vaccine depended on their current age and their age at the time MCV2 was introduced as part of RI in the geographic zone in which they resided. Before MCV2 was part of RI, children qualified if they were 24 months of age or older. After MCV2 became part of RI, children qualified if they were at least 15 months old at the time of the interview and younger than 24 months at the time of MCV2 introduction as part of RI.

Throughout the study, two cohorts were analyzed separately: children who were eligible for MCV2 before it was introduced as part of RI (cohort 1) and children who were eligible for MCV2 after it was introduced as part of RI (cohort 2). Additionally, in this paper, dropout refers to the difference in the vaccine uptake rate between the first and second measles vaccines, including before the introduction of MCV2 as part of RI, as MCV2 was available through SIAs.

Data

This study used the Nigeria Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2021.Citation17 MICS is a nationally representative household survey, and samples selected for the survey were representative of the state level. Nigeria has 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja. These 36 states and FCT are divided into six geopolitical zones: North Central, North East, North West, South East, South South, and South West.

MICS has multiple modules, including Household, Women, Birth History, and Children. The Children module contains questions about birth registration, early learning, breastfeeding, nutrition, immunization, anthropometry, malaria, and child development among children under 5. The Household module captures household characteristics, including the wealth index, which is the composite score based on assets and access to basic services such as water and sanitation. The Women module includes information, including on education levels, on women aged 15 to 49 who are members of households.

Analysis

The study first separately assessed the demographic characteristics of children in cohort 1 and cohort 2. The average demographic characteristics, such as child’s age, mother’s education level, and level of household wealth were evaluated for each cohort. Second, the average rates of measles vaccination and dropout from the first to the second dose were evaluated for each cohort and the geographical zone. Third, the correlation between the rates of measles vaccination uptake and dropout and demographic characteristics were evaluated for each cohort. Logistic regression was conducted to evaluate the correlation between the demographic characteristics of mothers and households and measles vaccine uptake and dropout, before and after the introduction of MCV2. Lastly, the correlation between the rates of measles vaccination uptake and dropout and demographic characteristics were also evaluated for each geographical zone.

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA MP version 18.0. The correlation was evaluated through logistic regression, and the STATA code used was “logistics.” Ethical approval for the study was waived, as the data used for the analysis were secondary, publicly available, and deidentified.

Outcome variables

Three main outcome variables were evaluated in this study: (a) whether a child received any measles vaccine, (b) whether a child received a second dose of the measles vaccine, and (c) whether a child received a first measles vaccine but not the second dose, or dropout.

Covariates

The main covariates included in the regression specification to evaluate the association between demographic characteristics and measles vaccine outcomes were mother’s educational attainment and household wealth index. State-level fixed effects were also controlled for. Throughout the study, we focused on two sociodemographic characteristics, namely maternal education level and level of household wealth, as potential key variables associated with vaccination behavior. The focus on these two variables and their correlation with vaccination likelihood was based on the literature. For example, Bobo et al.. (2022)Citation18 found that the distribution of vaccination coverage was pro-rich in most African countries, including Nigeria, and that vaccination uptake was largely correlated with maternal education and household wealth status. Vaccine uptake in Nigeria was pro-rich, meaning that zero or incomplete vaccination was concentrated among disadvantaged children. Other studies also found parental education and household wealth to have an important influence on vaccination in Africa.Citation19

Results

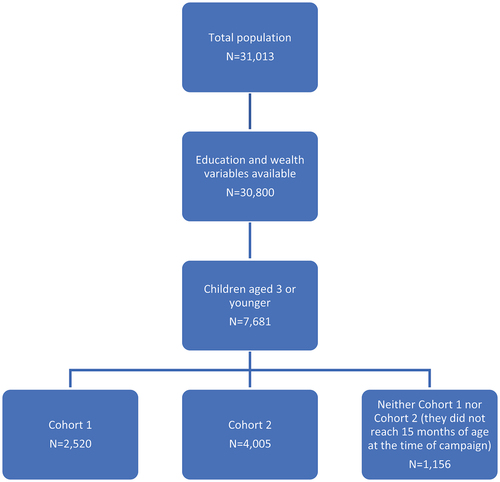

Before MCV2 introduction (cohort 1), 2,520 children were eligible to receive the second dose of measles vaccine and 4,005 children were eligible after the introduction of MCV2 as a part of RI (cohort 2). shows the flowcharts of the analysis sample. presents the summary statistics by cohort. Among cohort 1, the average age was 2.9 [95%CI: 2.37–3.46] years, 57% of whom had mothers with no education; 33% lived in the poorest households, while 6% lived in the richest households. Among cohort 2, the average age was 1.9 [95%CI: 0.54–3.21] years, 39% of whom had mothers with no education; 26% lived in the poorest households, while 11% lived in the richest households.

Table 1. Summary statistics.

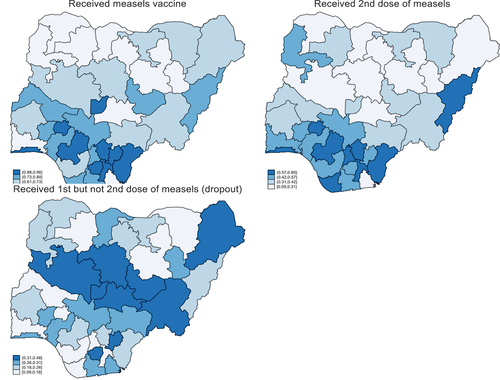

presents the outcome variables by cohort. The uptake of measles vaccine at the national level was similar between cohorts: In both cohorts, 71% [95%CI: 69.0–72.6] of children received the measles vaccine at any point and 43% [95%CI: 41.4–45.3] of children received the second dose of the measles vaccine. The dropout rate from the first to the second vaccine was 24% [95%CI: 22.6–26.0] to 25% [95%CI: 23.3–26.1]. At the zone level, the proportion of children having ever received the measles vaccine ranged from 55.5% [95%CI: 52.3–58.7] in the North West zone to 92.2% [95%CI: 89.7–94.8] in the South East zone among cohort 2. A similar trend was observed for the uptake of the second dose, ranging from 31.5% [95%CI: 28.5–34.5] in the North West zone to 67.7% [95%CI: 63.2–72.2] in the South East zone. The dropout rate was similar across all zones, around 21% to 22% [95%CI: 18.0–26.6], except in the North Central and North East zones, which showed higher dropout rates of 32.7% [95%CI: 29.1–36.3] and 27.2% [95%CI: 24.0–30.5], respectively.

Table 2. Measles vaccine uptake and dropout by cohort [CI95%].

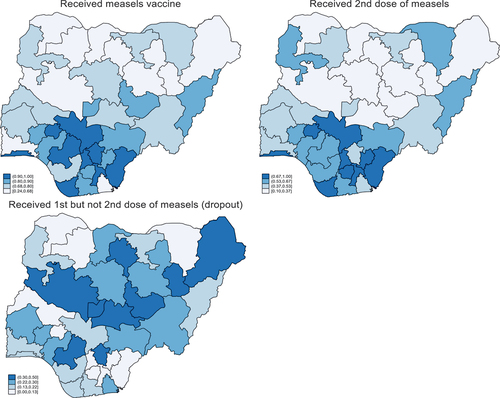

Among cohort 1, the trend of the proportion of children who had ever received the measles vaccine across zones was similar to that of cohort 2, but the intra-zone gap was narrower among cohort 1, ranging from 64.2% [95%CI: 62.2–67.3] in the North West zone to 95.1% [95%CI: 88.2–102.0] in the South East. On the other hand, the gap in the uptake of the second dose was wider among cohort 1, ranging from 38.6% [95%CI: 34.9–42.4] in the North East zone to 82.9% [95%CI: 70.9–95.0] in the South East zone. The dropout rate was the lowest in the South East zone at 12.2% [95%CI: 1.7–22.7], followed by 21%–22% [95%CI: 10.8–33.7] in the North West, South West, and South South zones. The highest dropout rates were observed in the North Central and North East zones, at 28.1% [95%CI: 24.8–31.3] and 26.2% [95%CI: 22.9–29.5], respectively.

present a visual map of measles vaccine uptake and dropout by state. present the geographical patterns of measles vaccine uptake and dropout among cohort 1 and cohort 2, respectively. For both cohort 1 and 2, the trend was consistent: higher measles vaccine uptake of both the first and the second dose of measles vaccine in the southern zones, and a higher dropout rate in the North Central zone.

presents the multivariable regression results for the association between measles vaccine uptake or dropout and sociodemographic characteristics. The regression was conducted separately for each cohort. For both cohort 1 and cohort 2, higher levels of maternal education and household wealth were correlated with the overall uptake of the measles vaccine and the second dose. The positive correlation between higher educational levels and the second dose was more prevalent and significant among cohort 2 than among cohort 1. Similarly, the positive correlation between higher household wealth level and the second dose was more prevalent among cohort 2 than among cohort 1.

Table 3. Association between measles vaccination uptake and dropout and demographic characteristics, before and after MCV2 introduction.

The dropout rate was strongly and positively correlated with the mother’s education level among cohort 2. In other words, the higher the mother’s level of education, the higher the dropout rate was among cohort 2. Household wealth level, on the other hand, was not associated with the dropout rate among cohort 2. Among cohort 1, the dropout rate from the first to the second dose showed little association with mother’s education level and was only weakly correlated with the level of household wealth.

presents the subgroup analysis of the association between the dropout rate and sociodemographic characteristics by zone. Among cohort 2, the strong positive correlation between education and the dropout was observed in the North West and South West zones. The household wealth level was significantly correlated with dropout only in the South East zone, and the correlation was negative.

Table 4. Association between dropout and sociodemographic characteristics, by zone.

Discussion

This study examined the trends of measles vaccine uptake and dropout, and the sociodemographic factors associated with them, before and after the introduction of MCV2 as part of RI. Overall measles vaccine uptake remained the same before and after the introduction of MCV2, which was about 71%, despite the children in cohort 2 being younger by 1 year. This trend indicates that measles vaccine uptake could improve further among cohort 2 after 1 year. Furthermore, the national average of vaccine uptake and dropout should be interpreted with caution, as MCV2 introduction varied by zone, with southern zones introducing MCV2 earlier than the northern zones did. This difference in timing affected the sample size in each zone, among cohort 1 and cohort 2.

Given the existing evidence that measles vaccine uptake is higher among children from better-off households,Citation12 it is important to examine whether and how the introduction of MCV2 influenced the distribution of measles vaccine uptake. The trend of children from more highly educated mothers and better-off households being more likely to receive the measles vaccine (both the first and second doses) remained the same or grew even more prevalent after MCV2 introduction. However, because we compared children in different age groups (older children for cohort 1 and younger children for cohort 2), this trend might simply mean that children from better-off households tend to take up the vaccine on time, whereas vaccine uptake tends to be delayed for other children, who tend to eventually catch up when reaching an older age.

However, what is more important to emphasize here is that this study also found that the dropout rate from the first to the second dose was positively correlated with the mother’s education level among cohort 2 after MCV2 introduction as part of RI, whereas this trend was not observed among cohort 1 prior to the introduction. Because education level is positively correlated with higher vaccine uptake, this result implies that children whose caregivers had lower education attainment were less likely to drop out from the first to the second dose compared to children whose caregivers’ education level was higher. This result is welcoming from a health equity standpoint. Since a positive correlation between education level and dropout was not observed among cohort 1, it is possible that MCV2 introduction as part of RI helped to narrow the equity gap in terms of measles vaccine uptake.

Most African countries reported pro-rich vaccination coverage, meaning that richer and more educated households enjoy better vaccination coverage.Citation18 Yet it has been observed that in some countries, certain interventions reduced the inequality of vaccination coverage (e.g., having access to the media reduced vaccination inequity in Liberia). The success of these pro-poor interventions might have been due to the concentrated efforts of healthcare workers to educate disadvantaged communities and households through door-to-door activities.

In Nigeria, interventions that prioritized reaching the vulnerable population to reduce vaccination inequities have also been implemented. Bawa et al.. (2018)Citation20 evaluated the effects of a program focused on hard-to-reach areas, which aimed to improve polio vaccine uptake in communities that had been hard to reach and had an elevated risk of wild poliovirus transmission in 2014. They found significant improvement in polio vaccine uptake in the selected areas, implying a narrowed equity gap of vaccine uptake.

The findings from the present study imply that MCV2 introduction might have narrowed the disparity of measles vaccine uptake, similar to the findings in the literature. Therefore, this intervention might have been an intentional effort by the government or health service providers to prioritize disadvantaged communities and households to ensure MCV2 penetration.

It is also important to note that a substantial variation in the correlation between sociodemographic characteristics and measles vaccine dropout was observed across zones. Specifically, the positive correlation between education level and dropout rates was observed only in the North West and South West zones. This result implies that the inequality in the measles vaccine uptake narrowed in the North West and South West zones, but health inequality remained the same between the first and second dose of the measles vaccine in other zones. Furthermore, a strong negative correlation between wealth level and dropout rate was observed in the South East zone, which implies that health inequities widened in the South East zone from the first to the second dose.

Within Nigeria, measles cases have been concentrated in northern zones, particularly the North East and North West zones, in the past 10 years.Citation7 Moreover, the North West zone reported the lowest vaccination coverage against measles (MCV1) throughout the country: merely 39%.Citation21 On the other hand, the South East zone has not recently witnessed a large-scale measles outbreak, and the vaccination coverage recorded there is one of the highest in Nigeria: 75% for MCV1.Citation21 These findings from the literature are largely consistent with the findings of the present study.

What has been missing from the literature, however, is the effects of newly introduced interventions such as MCV2 on households and children. In this sense, this finding of potentially narrowed inequity due to the introduction of MCV2, especially in the North West zone, has an important policy implication. In the period 2012–2016, the North West zone of Nigeria witnessed one of the highest measles burdens within the country.Citation22 Moreover, maternal education level is positively associated with MCV2 uptake. Because MCV2 introduction benefited the disadvantaged households with lower maternal education and that are at higher risk of household members contracting measles in the North West zone, MCV2 introduction could drastically reduce the prevalence of measles in Nigeria. A potential reason the North West zone was successful in narrowing health disparity in terms of measles vaccine uptake could be that the zone might have better planned and prepared for the introduction of MCV2 into RI. Richard et al. (2021) mentioned that northern zones were generally better prepared for immunization activities than southern zones because more technical consultants were recruited due to the higher burden of vaccine-preventable diseases, and these consultants guided immunization activities.Citation23 Other zones should employ the strategies used in the North West and South West zones to better prepare for immunization activities to target the vulnerable population to narrow the disparity in measles vaccine uptake, which would result in the overall reduction of measles cases. Future studies should examine how each zone conducts the new RI program that includes MCV2 and how RI reaches children, which might have a different effect on health inequities. Future study should include regional researchers to explore further and more in details on potential interventions that can better fit into each region for the improved vaccine uptake.

Limitations

The sample size of children who fell into each time period, pre- and post-MCV2 introduction, was small because the government launched MCV2 as a part of RI between 2019 and the beginning of 2021, and the survey was conducted in late 2021. The small sample size might have caused a misrepresentation of statistical results in that there might not have been enough power to be able to detect the significance in correlation. In this sense, the small sample affects the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, we had a short time to track children in cohort 2. It is important to keep track of children for a longer time to fully understand how MCV2 introduction influences health inequities. Lastly, while vaccine uptake and dropout depend on multiple factors including social determinants, economic and logistic factors, health worker capacity, and reporting and surveillance, this study exclusively focused on the effect of newly-introduced vaccine as part of the routine immunization (RI) program.

Conclusion

We found that an overall measles vaccine uptake of over 70% was achieved at an earlier age after MCV2 introduction as part of RI. The result further indicates that MCV2 introduction might have narrowed the inequities in measles vaccine uptake in the North West and South West zones but not in other zones. This result has an important policy implication for reducing health inequities in Nigeria. Zones that did not experience reduced disparities concerning vaccine uptake due to the introduction of MCV2 should employ the strategies used in the North West and South West zones to target the vulnerable population, which would result in a reduction in overall measles cases. It is recommended that future studies identify which strategies used in the introduction of MCV2 might have contributed to reducing inequities in measles vaccine uptake.

Author contributions

RS conceived the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was waived, as the data used for the analysis were secondary, publicly available, and deidentified.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable, as the data used were secondary data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Orenstein WA, Ahmed R. Simply put: vaccination saves lives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(16):4031–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1704507114.

- Ehreth J. The global value of vaccination. Vaccine. 2003;21(7–8):596–600.

- Meissner HC Strebel PM, Orenstein WA. Measles vaccines and the potential for worldwide eradication of measles. Pediatric. 2004;114(4):1065–9.

- National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Division of Viral Diseases. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/history.html.

- Khanal S, Kassem AM, Bahl S, Liyanage J, Sangal L, Sharfuzzaman M, Sekhar Bose A, Antoni S, Datta D, Alexander JP Jr. Progress toward measles elimination—South-East Asia region, 2003–2020. Morbidity Mortal-Ity Weekly Rep. 2022;71(33):1042.

- Masresha BG. Progress toward measles elimination—African region, 2017–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72.

- Sato R, Ayodeji Makinde O, Clement Daam K, Lawal B. Geograph-ical and time trends of measles incidence and measles vaccination coverage and their correlation in Nigeria. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(6):2114697.

- Majekodunmi OB, Oladele EA, Greenwood B. Factors affecting poor measles vaccination coverage in sub-Saharan Africa with a special focus on Nigeria: a narrative re-view. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2022;116(8):686–93.

- Gebeyehu NA, Asmare Adela G, Dagnaw Tegegne K, Birhan Assfaw B. Vaccination dropout among children in Sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(7):2145821.

- Aguinaga-Ontoso I, Guillen-Aguinaga S, Guillen-Aguinaga L, Alas-Brun R, Onambele L, Aguinaga-Ontoso E, Guillen-Grima F. COVID-19 impact on DTP vaccination trends in Africa: a joinpoint regression analysis. Vaccines. 2023;11(6):1103.

- Baptiste AEJ, Masresha B, Wagai J, Luce R, Oteri J, Dieng B, Bawa S. Trends in measles incidence and measles vaccination coverage in Nigeria, 2008–2018. Vaccine. 2021;39:89–95.

- Shearer JC, Nava O, Prosser W, Nawaz S, Mulongo S, Mambu T, Mafuta E. Uncovering the drivers of childhood immunization inequality with caregivers, community members and health system stakeholders: results from a human-centered design study in DRC, Mozambique and Nigeria. Vaccines. 2023;11(3):689.

- Antai D. Inequitable childhood immunization uptake in Nigeria: a multilevel analysis of individual and contextual determinants. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:1–0.

- Sato R, Fintan B. Effect of cash incentives on tetanus toxoid vaccination among rural Nigerian women: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2020;16(5):1181–8.

- Olorunsaiye CZ, Shaw Langhamer M, Stuart Wallace A, Lyons Watkins M. Missed opportunities and barriers for vaccination: a descriptive analysis of private and public health facilities in four African countries. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27(Suppl 3):6.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global measles and rubella strategic plan: 2012-2020. 2012 [accessed 2023 Dec 3]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241503396.

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2021; 2022 Aug. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/5959.

- Bobo FT, Asante A, Woldie M, Dawson A, Hayen A. Child vaccination in sub-Saharan Africa: increasing coverage addresses inequalities. Vaccine. 2022;40(1):141–50.

- Ndwandwe D, Uthman OA, Adamu AA, Sambala EZ, Wiyeh AB, Olukade T, Bishwajit G, Yaya S, Okwo-Bele JM, Wiysonge CS. Decomposing the gap in missed opportunities for vaccination between poor and non-poor in sub-Saharan Africa: a multicountry analyses. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14(10):2358–64.

- Bawa S, Shuaib F, Saidu M, Ningi A, Abdullahi S, Abba B, Idowu A. Conduct of vaccination in hard-to-reach areas to address potential polio reservoir areas, 2014–2015. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:113–20.

- National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF. Nigeria demographic and health survey 2018. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF; 2019.

- Ibrahim BS, Usman R, Mohammed Y, Datti Z, Okunromade O, Ahmed Abubakar A, Mboya Nguku P. Burden of measles in Nigeria: a five-year review of casebased surveillance data, 2012-2016. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;32(Suppl 1):5.

- Richard MT, Taiwo L, Baptiste AEJ, Bawa S, Dieng B, Wiwa O, Lambo K, Braka F, Shuaib F, Oteri J. Planning for supplemental immunization activities using the readiness assessment dashboard: experience from 2017/2018 measles vaccination campaign, Nigeria. Vaccine. 2018;39(2021):C21–C28.