ABSTRACT

The contribution of vaccination to global health, especially in low-middle-income countries is one of the achievements in global governance of modern medicine, averting 2–3 million child deaths annually. However, in Nigeria, vaccine-preventable-diseases still account for one-in-eight child deaths before their fifth-year birthday. Nigeria is one of the ten countries where 4.3 million children under five are without complete immunization. Therefore, the goal of this contribution is to shed light on the reasons to set a foundation for future interventions. To conduct focus groups, a simplified quota sampling approach was used to select mothers of children 0–12 months old in four geographical clusters of Nigeria. An interview guide developed from the 5C psychological antecedence model was used (assessing confidence, complacency, calculation, constraints, collective responsibility); two concepts were added that had proved meaningful in previous work (religion and masculinity). The data were analyzed using a meta-aggregation approach. The sample was relatively positive toward vaccination. Still, mothers reported low trust in vaccine safety and the healthcare system (confidence). Yet, they had great interest in seeking additional information (calculation), difficulties in prioritizing vaccination over other equally competing priorities (constraints) and were aware that vaccination translates into overall community wellbeing (collective responsibility). They had a bias toward God as ultimate giver of good health (religion) and their husbands played a dominant role in vaccination decision-making (masculinity). Mothers perceived their children vulnerable to disease outbreaks, hence, motivated vaccination (complacency). The study provided a useful qualitative tool for understanding mothers’ vaccination decision-making in low resources settings.

Introduction

Since start of the new millennium, vaccine coverage in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) for vaccine-preventable-diseases (VPDs) has surpassed multiple milestones and expectations, although serious work are still to be done to meet targets.Citation1 Nonetheless, the contribution of vaccination to global health, especially in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) is one of the achievements in global governance of modern medicine, averting over 4 million deaths every year.Citation2,Citation3 Besides the protection from VPDs, immunization services had indirectly brought vulnerable children and families into contact with healthcare systems, which has created avenues for the delivery of other primary healthcare services such as family planning, maternal healthcare services, counseling, patient education, diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic illnesses and many others.Citation2,Citation3

Nigeria’s immunization coverage has made significant progress in the last years, ensuring that children under five years old (under-5) have access to health and routine immunization services.Citation4 This has resulted in a significant shift compared to the decade before, e.g., the uptake of three doses of Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis (DTP3) increased from 44% in 2015 to 57% in 2020.Citation4 This is a good progress, especially when considering that vaccination coverage of children 12–23 months had dropped within the same period (2008–2013) by 10%.Citation5 While these gains are seen in recent data,Citation4 Nigeria remains one of the 10 countries in the world where 4.3 million children under-5 are without complete immunization owing to a convolution of factors especially vaccine hesitancy.Citation6 United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) classifies the country as one of the worst places in the world to raise a child or infant, or to be a mother.Citation7 Thus, to develop and implement suitable interventions to foster uptake, vaccine hesitancy, i.e., the drivers and barriers of vaccination decision makingCitation2,Citation8,Citation9 need to be understood.Citation10,Citation11

The Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) defines vaccine hesitancy as a “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services.”Citation12,Citation13 This definition suggests that vaccine hesitancy is rather a demand rather than a supply-side problem, focusing on several individual behavioral factors such as the risks related to vaccinating, concerns about adverse events, religious compatibility, or lack of trust in general.Citation14 Yet, lack of access or availability is also seen as a constraining factor and included in some models.Citation8 Most of the research on vaccine hesitancy and interventions to reduce it stems from high-income countries (HICs).Citation8–Citation9-15–Citation20 One of such models that have been validated in several settings including LMICs is the 5C psychological antecedence model.Citation1–9-Citation15–23

Therefore, the goal of the study was to gain deeper insights into vaccination decision-making or behavior among mothers of children 0–12 months old in Nigeria using the 5C psychological antecedence model, gaining data on enablers and barriers of vaccination behavior in the understudied setting. Similarly, the study outcome can support the evidence-based design of appropriate interventions to address low vaccination uptake, not just in Nigeria but also in other SSA countries.

Methods

The 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination decisions

The 5C model has been tested and validated only in quantitative form. This study used the model (for the first time) as a framework for a qualitative approach. This allows building upon existing theoretical knowledge but at the same time enables an open process supporting a broader understanding of relevant factors affecting vaccination decision making in the SSA region.

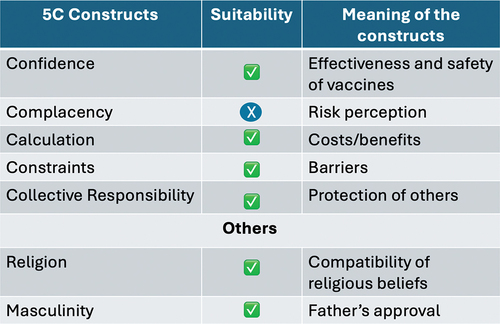

The 5C model of vaccines hesitancy is composed of five psychological antecedents of vaccination behavior: confidence, complacency, constraints, calculation, and collective responsibility.Citation8 Confidence is the trust in the effectiveness and safety of vaccines. Complacency denotes low risk perception of vaccine-preventable diseases and vaccination deemed not a necessary preventive action. Constraints exist when physical availability, affordability, or geographical accessibility negatively affect immunization uptake. Calculation refers to individuals’ engagement in extensive information search and assessment of cost-benefit analysis of vaccination decisions. Collective responsibility is the willingness to protect others by one’s own vaccination decision or action. In addition to the 5C, two additional constructs proved relevant in previous work in Nigeria: religion (i.e., compatibility of vaccination with religious beliefs) and masculinity (i.e., importance of father’s approval) were related to less vaccine uptake.Citation1,Citation8

Study design and sampling

Four focus group discussions (FGD) were conducted. Primarily, the target group were mothers of children 0–12 months old in Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory. The territory was divided into four clusters. One healthcare facility was randomly selected from each cluster, from which participants (mothers attending antenatal services) were randomly selected. Of the four clusters, two were urban (Maitama and National hospital areas), while the other two were suburban/rural (Karu and Garki areas). A simplified quota sampling approach was used to select eligible mothers. The selected clusters had consideration for geographical representation and areas that offers immunization services since a year before the study was conducted. Six (6) mothers whose children were between 0–12 months old were randomly included from each cluster, giving a total of 24 participants. I.e., each FGD consisted of 6 randomly selected eligible participants.

Data collection process

Study participants were provided with an information sheet stating the goals and expected outcomes of the study. All participants consented to be included. The data collection was conducted between September 20–27, 2019 in the Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory. The FGDs were audio recorded and explored perspectives of caregivers on factors that influence vaccination decision-making for their children.

Focus group discussion guide

A semi-structured FGD guide modeled on the 5C framework was used to lead the discussions. This allows building upon existing theoretical knowledge but at the same time enables an open process supporting a broader understanding of relevant factors affecting vaccination decision making in the SSA region. It explored main topics such as: Confidence (“In your experience as a mother, how would you assess your level of trust in the safety and effectiveness of vaccination? Follow-Up: How about the general health system delivering it?”); Complacency (“In your view, how would you consider continuing polio vaccination for your child, despite very few cases around you?”); Calculation (In your experience, how useful is searching for more information helpful in deciding whether to vaccinate your child or not?”); Constraints (“In your experience, what makes getting vaccinated easy, what makes it hard? Follow-up: if hard … why and how did you overcome them and if easy, what makes it easy?”); Collective responsibility (“In your view, how does vaccinating your child affect other children in the neighborhood?”); Religion (“How does your religion perceive vaccination? Follow-up: what do you think about prayers to prevent diseases?”) and Masculinity (“How would you describe the role of your husband when it comes to vaccination? Follow-up: how important is husband’s approval?”). Despite being guided by these questions; the moderator was flexible in relations to unrelated but relevant follow-up questions.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using a meta-aggregation technique (framework synthesis), which seeks to summarize data in a stepwise fashion and assesses themes based on predefined concepts.Citation24,Citation25 Convergence and divergence of views based on each of the pre-defined measures/themes were identified (second-order data) after analyzing each individual transcript (first-order data) and categorized based on the aggregation of subject outcomes (third-order data). All recorded discussions were transcribed verbatim and stored in a password protected drive. The participants were coded based on name of the clusters (e.g., participants 1 through 6 at Garki as G001–6, at Karu as K001–6, at Maitama as M001–6 and at the National Hospital area/Heinrich Böll Stiftung (HBS) center as HBS001–6). The transcribed data were coded by the first author and structured along the 5C. The coding and themes development followed the deductive approach. The additional themes were explored inductively.

Results

Participants

Out of the participants, 42% were first time mothers, while 58% were mothers who have had at least one previous child. The youngest participant was 21 years old, while the oldest was 38. All participants were married. The majority of the mothers had tertiary education (83%), while 17% have attended secondary school. In terms of geographical distribution, the majority of the participants were from the North-Central (29%) and South-East (25%), while none participated from the North-East. Others were South-South (4%), South-West (17%), North-West (17%), while 8% of the participants did not indicate regions of origin. 17% of the participants were civil servants, 13% worked for non-government institutions or companies, 25% of the mothers were self-employed, 17% were unemployed, 25% were housewives and 3% indicated “other” for employment status.

Drivers of childhood vaccine uptake

The analysis revealed the following factors driving mother’s vaccination decision-making or behavior. Besides the model-based factors (5C plus religiosity and masculinity) we coded attitudes and knowledge as extra categories to better understand the content and ideally also the reasons why mothers had the particular attitude or knowledge. Theoretically, attitudes belong to the confidence constructCitation8; knowledge can pertain to several factors (e.g., knowledge about herd immunity to collective responsibility, knowledge about disease risks to complacency, etc.).

Positive attitude toward immunization

Many mothers had a positive attitude toward childhood immunization, even prior to childbirth. Most of the mothers mentioned the importance and advantages of childhood vaccination. Antenatal clinic (ANC) attendance during pregnancy was mentioned in relation to the positive attitude.

My opinion about immunization has always been the same because I don’t play with it. In fact, I go to the extent that if they say they don’t have that particular vaccine, I will go to a private hospital to make sure my child gets immunized. (M001)

Before the child was born, I knew I would be taking her for immunization in town … and so far, we have been good. My opinion has not changed. (HBS001)

[…] before I had my baby, I was curious and not sure about immunization, especially when I see how they cry. I will ask, is immunization necessary or important? I felt like they were just stressing the children, not until I started ANC. In antenatal class I got to know why immunization is important and I don’t object to it anymore […]. (K004)

Increase but insufficient knowledge of immunization

While mothers felt that their knowledge was enhanced because of ANC attendance, the knowledge provided may be insufficient. Many caregivers associated immunization with important preventive measure against viral, airborne, local diseases outbreaks or all childhood diseases. Palpable disappointment occurred, when caregivers had found out that immunization cannot protect their children from all childhood diseases, contrary to earlier assumption. Many mothers assumed that the chances of contracting any childhood disease (vaccine preventable or not) are lower once children are vaccinated.

The first thing that comes to my own mind is that immunization prevents diseases 100%. I know even if there is a disease breakout, the chances that my child will be infected will be low … he has immunity, that’s what I know. (HBS001)

Anytime I hear immunization it means protection of my child from diseases like chicken pox, malaria, measles, diarrhea, meningitis … it saves my child from so many sicknesses. (G001)

When I hear the word immunization … it is a way of preventing the baby from diseases. (K001)

Confidence

While trust in vaccine effectiveness was high, the trust in safety and the government or the healthcare system was low among mothers. However, there was lower trust in the government due to politics/rumors, general distrust in politicians, as well as monetization of vaccines at the health facilities. Similarly, lower trust in the healthcare system was associated with perceived lower competencies of the healthcare workers (HCWs), as well as corruption at the health facilities.

[…] We can’t say the trust is 100%, but more than 60%. The reason is vaccine safety concerns … has it expired … when did they produced it … how long was it in the warehouse … how was it handled…and so many questions? So, for all those things, it gives a little doubt. (HBS001)

[…] my advice is that mothers should go to a good hospital where HCWs are well trained. (HBS003)

For the government, I think I will give them 55% trust, because immunization services were supposed to be free and compulsory, yet they charge money … so, government must make immunization free as they claim, so that parents can have access to it … .For the HCWs, they should get experienced and well-trained ones … more mother will receive immunization if the HCWs are perceived to be well trained. (HBS003)

[…] don’t trust government because they always put politics ahead of our wellbeing. (M004, Maitama)

Complacency

Contrary to the findings in HIC, where complacent behavior was associated with perceived low risk of VPDs,Citation8 most mothers in this study recognized the risk associated with VPDs. The awareness that herd immunity was low and the consequent vulnerability of their children to disease outbreaks was discussed as a motivation for vaccination.

We immunize for polio or any other disease because it may come back, or the child may contract polio because we are not 100% sure that the disease is gone completely. (HB002)

[…] so, it is good to keep immunizing, just in case you happen to travel with your child to a place where it is prevalent. (K006)

[…] even though I do not travel, someone else might travel and return with a vaccine-preventable disease. (G002)

it’s very necessary to continue to vaccinate as many children as possible even though it is not common anymore, because there are places that might still have it. (G004)

Calculation

While the efforts put into seeking vaccination information may differ between mothers, nevertheless it was a very important activity. Several mothers referenced the health facilities, especially the ANC health talks, as a significant source of information on immunization. Besides the health talk, advice from relatives, friends and peers in their community were equally useful sources of vaccination information. One of the reasons for information search was usually the desire to have a better understanding of certain health conditions and to know more about the right dosage of the vaccines. The participant’s inference of dosage could equally connote vaccination schedule.

Most of the information I get are from the hospital. Although, it is not everything. I also enquire from other mothers in the community who are more experienced. (M004)

Before I got married and had my child, I use to follow one of my aunties to the hospital to seek information about childcare. From that experience, I learnt a lot about ANC, immunization and vaccine dosage beforehand. (G003)

I am always curious; I just want to know more before giving my child vaccines … it is good to search for more information. (K004)

Constraints

A frequently reported barrier to vaccination was a tight schedule of the mothers, which made it hard to fit vaccination appointment into their daily routines and to prioritize immunization ahead of other equally competing duties. Other constraints that influenced vaccination decision-making or behavior of mothers were long waiting hours at the clinic, disrespectful attitude of HCWs, and the difficulty in dealing with adverse events from immunization (AEFI).

[…] most of us who have other children … we have to prepare the older ones for school, prepare food for the family, prepare the new baby, and then prepare oneself in order to meet the vaccination appointments and so on. Thereafter, we will return and still go to work. So, it is very stressful to juggle everything. (K001)

It is a very challenging because sometimes you have to leave your work. More so, sometimes after immunization injections, the child cries the whole day. Your day won’t go as planned. (G003)

On immunization days, I have to wake up at 04:30 to prepare breakfast, bath the other children and go to the clinic early, so that I will be among the first mothers to arrive on the queue. If I cannot be among early arrivals to queue, I will spend the whole day at the clinic due to long waiting hours. (HBS004)

[…] the poor attitude of the HCWs, especially the Nurses,’ discourages mothers from attending immunization … the nurses insults and disrespect mothers at the slightest provocation. They can say anything to you. (HBO002)

Collective responsibility

While mothers saw the benefits of vaccinating their children, they were equally conscious of the communal benefits if everyone does so. They saw one’s own vaccination as a responsibility to protect other children in the community.

I think it is the responsibility of every parent to immunize their children because if they do not, it might affect everyone. E.g., if there is a measles outbreak, my child will go to school and mingle with other children and can be infected” (HBS001). “[…] so, if your own child is immunized, you have reduced the consequences. (K004)

The essence of vaccination is to equally help my neighborhood, because when I vaccinate my child, indirectly I am immunizing everybody in my neighborhood. (M002)

I will vaccinate my child to protect other children around. (G003).

Religion

Mother’s perception of immunization was in line with their religious beliefs. They assumed that praying to God was also relevant as God is the ultimate giver of good health. The perception that prayers prevent diseases differed among mothers. Some viewed prayers as an important health add-on to immunization. Prayers alone were yet not viewed as protection against VPDs.

I pray to God, but I do my own duty as well, i.e., I go for immunization. (HBS002)

Prayers work against diseases, but also, receiving immunization is the right thing (G002).

I don’t believe prayers prevent diseases; you have to take immunization (M002).

The act of getting your child vaccinated is also an act of faith in vaccines. (K004)

Masculinity

Mothers reported that husbands or the child’s father played a dominant role in the vaccination decision-making process of their children. Immunization of children were most likely when husbands or fathers had positive attitude toward vaccination. Mothers need approval of the husbands for vaccination of their children.

I need his approval whether I like it or not, because I cannot go if he tells me not to go. (M004)

Obedience comes first … but he has been supportive because, he is the one that even reminded me to go and register for immunization. (HBS002)

The husband is also in charge of the transportation and pays for the vaccines … even when I forget, he will wake up in the morning and do house chores, take me to the clinic, give me transport money and then he goes to work. (G001)

Discussion

The study has provided an extended understanding of vaccination decision-making and behavior of mothers of infants in Nigeria using the 5C model in a qualitative study. provides an overview of the constructs coded and the outcomes in the study. The sample was generally relatively positive toward vaccination. Still, mothers reported low trust in vaccine safety and the healthcare system (confidence). Yet, they had great interest in seeking additional information during antenatal visits (calculation), difficulties in prioritizing vaccination over other equally competing priorities (constraints) and were aware that vaccination translates into overall community health and wellbeing (collective responsibility). They saw God as ultimate giver of good health (religion) and reported that their husbands played a dominant role in vaccination decision-making (masculinity). Mothers perceived their children vulnerable to disease outbreaks, which motivated them to get them vaccinated (complacency). The study outcome can be very valuable to the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) in Nigeria, because it generated an improved understanding of mother’s perception of healthcare services delivery and mother’s behavior or decision-making determinants in Nigeria.

Previous quantitative work using the 5C model in Nigeria has shown that not all components of the model were relevant when they were measured with the original scale.Citation1,Citation15 Yet, the present results suggest that cultural adaptation may be promising and encourage a quantitative use of an extended 5C model in the LMICs or SSA.Citation1,Citation15 In the previous quantitative 5C study in Nigeria, vaccination behavior was influenced by confidence, collective responsibility, constraints and mothers’ religious belief.Citation1 In this study as seen in , perhaps due to the possibility to answer freely to the questions at hand, the results suggest that confidence, calculation, constraints, collective responsibility, religion and masculinity may be relevant – while complacency was not a relevant barrier. Thus, the results converge, but more factors than before appear relevant.

As issues related to confidence, mother’s low trust in the government or healthcare system, general distrust of politicians, as well as the perceived corruption at the clinics came up. Building trust, not necessarily in the government but in the healthcare system, should be at the center of new interventions, as trust has proven to be a significant determinant of effective behavior change and management of public policy.Citation26,Citation27 The EPI should be proactive about the fact that some HCWs are financially exploiting mothers using the recommended immunization that is supposed to be free. It would be almost impossible for vaccination demand to improve or to counter vaccine hesitancy in Nigeria if the current distrust between the demand and supply sides of immunization are not addressed. A potential strategy could be to consider a stronger relationship that reconnects the healthcare system and the community gatekeepers.Citation2 This could reduce the communities’ overt suspicion and lack of trust of the healthcare system including HCWs and the government. Moreover, the regulatory authorities need to ensure adequate monitoring of the healthcare facilities to prevent abuse and exploitation of caregivers, especially on services that are supposed to be free such as the nationally recommended childhood vaccines.

In addition, HCWs should be routinely trained not just on knowledge of immunization to prevent mis- or inaccurate information about the effectiveness of vaccines, but also on general healthcare practices and ethics, to shore-up confidence of mothers in the healthcare system and knowledge on diseases vaccines can prevent versus those they cannot.

Most mothers in this study were not complacent. They were rather aware of low herd immunity in the communities and the consequent vulnerability of their children to disease outbreaks. The fear that their children could bear the burden if a VPD outbreak occurs motivated mothers to immunize their children. This finding may be credited to the strength of the current Nigerian immunization campaigns that stresses the severity of VPDs, although it needs to be noted that this has not (yet) translated into vaccination uptake. This finding reflects a high concern for and awareness that children need protection from VPDs using immunization.

The importance of seeking additional information to support mother’s vaccination decision was a novel finding. Mothers reported that the health talks provided during visits of ANC were a primary source of vaccination information. Thus, targeting pregnant women with immunization information seems effective. Yet, it also implies that those women who do not attend such classes are hard to be reached. Mothers also mentioned other important sources of vaccination information including non-medical sources such as relatives and peers in their communities. Therefore, further vaccination education should move beyond targeting mothers alone, but the entire households and communities. The current data did not reveal clear evidence on which sources led women toward or away from vaccination, however, attendance at ANC seemed to support a positive view on vaccination.

As obtained in HICs, mothers in Nigeria were also inundated with frequently reported constraints such as prioritizing vaccination ahead of other equally competing priorities within their everyday schedule. Also, the long waiting hours at the health facilities makes working mothers’ immunization planning very difficult. Interventions addressing this (e.g., day off on immunization days) may be helpful to improve compliance.

Another noticeable factor linked to constraints was the perceived poor attitude of HCWs. There is a noticeable ethics problem on conducts and practices among HCWs in the healthcare facilities. This requires urgent administrative intervention. Therefore, the federal and state ministries of health, National Primary Healthcare Development Agency (NPHCDA) and other institutions responsible for deploying HCWs to healthcare facilities across the country must rise to this trend. Among others, it should include retraining of HCWs on code of conducts of healthcare professionals.

Even though religion did not turn out to be a major barrier, God was seen as a major source of health and wellbeing. The notion of prayers as prevention of VPDs did not have the strongest support among participants. Yet, it was also not completely discarded and rather seen as an additional intervention.

Similarly, participants appreciated the support of their husbands or child’s father. However, to the extent that some of their husband’s role in immunizing children was commendable, they played a dominant role in the vaccination decision-making process of the children. Most participants reported that they seek approval of the husbands for vaccination of their children. This study findings validated a previous one that revealed that childhood vaccination was more likely when it is in line with father’s attitude and vice versa.Citation1

This study found generally positive attitudes toward immunization among the sample of Nigerian mothers. However, knowledge about vaccines and the diseases that they prevent was still inadequate. This is similar to some studies in the SSA, where caregivers have the wrong assumptions that childhood vaccination can prevent all childhood diseases.Citation14,Citation28 There seems inadequate knowledge among caregivers on distinctions between VPDs and other diseases in general. This inadequacy of knowledge about immunization fuels the assumption that immunization will prevent all childhood diseases. Therefore, when a child is ill with a disease, whether vaccine-preventable or not, mother’s confidence in immunization may drop. Since the antenatal visits appeared a relevant source of information for mothers, investments in highly resourced facilitators are essential to properly educate the mothers about the benefits and limitations of vaccination.

Another key contribution of this study is the use of the 5C model as a theoretical framework for understanding vaccination decision making or behavior in low resource setting such as the SSA. The use of qualitative methods to test and adapt the 5C model seems advisable and can be considered well-suited to challenge and adapt models. The study was helpful in informing future studies, but also would have profited from asking more open-ended questions when adapted. That way, potential other constructs that had not been considered beforehand can come up.

The study is not without limitations. First, the FGD guide was standardized and pre-informed by the 5C model, including direct questions touching upon the item content of the scale in the interview questions (e.g., “how would you assess your level of trust?”). Second, the tendency of focus group participants to give socially desirable answers in group settings may be higher compared to in-depth interviews. However, the FGD is a very efficient and effective method and convincing for this particular study, because it allows participants (who share similar experiences as mothers) to feed off on each other’s responses and generate new ideas which might not have been thought of in an individual interview. Also, these concerns did not affect how participants perceived or understood the questions and responded, because simplification of the 5C model into themes for proper understanding of participants helped to overcome the anticipated barriers.

Conclusion

The study has allowed a deeper insight into understanding what lies behind relevant antecedents of maternal vaccination behavior in Nigeria. Using the 5C model for setting up the guide for a FGD provided multiple opportunities for adapting the measurement model toward understanding vaccination decision-making, especially in SSA setting. In addition, the use of the 5C model in qualitative research can play a significant role in generating an improved understanding of caregiver’s perception beyond some predefined judgments in quantitative studies and help generate very concrete ideas on how to improve on the identified barriers.

The question of whether the 5C model is flexible enough to be used in SSA/LMICs more generally, since its foundations originated from the Global North, can be confirmed. Based on the outcomes of this study, the 5C model, upon cultural adaptation and validation, has shown as a useful instrument for assessing childhood vaccination behavior or decision making in a low resource setting. This is not without the combination with religion and masculinity as factors, especially in the SSA setting. Further replication across multiple SSA region seems advisable to properly finetune the instruments.

List of abbreviations

| EPI: | = | Expanded Program on Immunization |

| DTP3: | = | Diphtheria Tetanus Pertussis |

| GAVI: | = | Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization |

| HPV: | = | Human Papillomavirus |

| SSA: | = | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| UNICEF: | = | United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund |

| WHO: | = | World Health Organization |

| WUENIC: | = | WHO/UNICEF Estimates of National Immunization Coverage |

| FGD: | = | Focus Group Discussion |

| RI: | = | Routine Childhood Immunization |

| Q&A: | = | Question and Answer |

| MoH: | = | Ministry of Health |

| H2R: | = | Hard-to-reach |

| VPDs: | = | Vaccine-preventable diseases |

| HCWs: | = | Healthcare Workers |

| HBS: | = | Heinrich Böll Stiftung |

| ANC | = | Antenatal Care |

| AEFI | = | Adverse Event from Immunization |

| NPHCDA | = | National Primary Healthcare Development Agency |

| HICs | = | High Income Countries |

| SAGE | = | Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) |

| LMICs | = | Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC) |

Author’s contribution

Conceptualization: GCA and CB.

Methodology: GCA and CB.

Investigation: GCA.

Result Analysis: GCA.

Writing – original draft: GCA and CB.

Writing – review & editing: GCA and CB.

Consent for publication

All authors approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available at https://osf.io/aqzk4/.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Nigerian Health Research Ethics Committee (reference number FHREC/2018/01/99/03-09-2018/19). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Acknowledgments

The study acknowledges the management and staff of Maitama District Hospital, Abuja; Karu Primary Health Centre, Abuja; Garki Primary Health Centre, Abuja. Also, acknowledgment goes to Heinrich Böll Stiftung (HBS), Abuja, for its tremendous support and use of its conference room for meetings during the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adeyanju GC, Sprengholz P, Betsch C. Understanding drivers of vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women in Nigeria: a longitudinal study. NPJ Vaccines. 2022;7(96). doi:10.1038/s41541-022-00489-7.

- Adeyanju GC, Betsch C, Adamu AA, Gumbi KS, Head MG, Aplogan A, Tall H, Essoh T-A. Examining enablers of vaccine hesitancy toward routine childhood and adolescent vaccination in Malawi. Interact Stud. 2022;7(1):28. doi:10.1186/s41256-022-00261-3.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Immunization coverage. Geneva. 2019 Dec 5. [accessed 2022 Mar 29]. https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/immunization.

- WHO/UNICEF Estimates of National Immunization Coverage (WUENIC). Immunization coverage estimates data visualization. 2021 Jul. https://data.unicef.org/resources/immunization-coverage-estimates-data-visualization/.

- Nigeria demographic and health surveys (NDHS). Report 2018. [accessed 2022 May 20]. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR359/FR359.pdf.

- UNICEF. News note: 4.3 million children in Nigeria still miss out on vaccinations every year. Press release. 2018 Apr 23. [accessed 2022 Mar 28]. https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/press-releases/news-note43-million-children-nigeria-still-miss-out-vaccinationsevery-year.

- UNICEF. Levels and trends in child mortality. United Nations inter-agency group for child mortality estimation (UN IGME). Report 2020. [accessed 2022 Jan 3]. https://data.unicef.org/resources/levels-and-trends-in-child-mortality/#.

- Betsch C, Schmid P, Heinemeier D, Korn L, Holtmann C, Bohm R, Angelillo IF. Beyond confidence: development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(12):e0208601. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208601.

- Larson HJ, de Figueiredo A, Xiahong Z, Schulz WS, Verger P, Johnston IG, Cook AR, Jones NS. The state of vaccine confidence 2016: global insights through a 67-country survey. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:295–8. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.042 PMID: 27658738.

- Chu HY, Englund JA. Maternal immunization. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(4):59; 560–568. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu327.

- Obanewa OA, Newell ML. The role of place of residency in childhood immunisation coverage in Nigeria: analysis of data from three DHS rounds 2003-2013. BMC Public Health. [accessed 2020 Jan 29]. 20(1):123. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-8170-6.

- WHO/UNICEF Coverage Estimates 2018 revision. 2019 Jul [accessed 2022 Apr 15]. https://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/timeseries/tswucoveragedtp3.html.

- Piot P, Larson HJ, O’Brien KL, N’kengasong J, Ng E, Sow S, Kampmann B. Immunization: vital progress, unfinished agenda. Nature 2019. 2019;575(7781):119–29. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1656-7.

- Ophori EA, Tula MY, Azih AV, Okojie R, Ikpo PE. Current trends of immunization in Nigeria: prospect and challenges. Trop Med Health. 2014;42(2):67–75. doi:10.2149/tmh.2013-13.

- Adeyanju GC, Sprengholz P, Betsch C, Essoh T-A. Caregivers’ willingness to vaccinate their children against childhood diseases and human papillomavirus: a cross-sectional study on vaccine hesitancy in Malawi. Vaccines 2021a; Nato Adv Sci Inst Se. 2021;9(11):1231. doi:10.3390/vaccines9111231.

- MacDonald NE, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036 PMID: 25896383.

- Thomson A, Robinson K, Valle ́e-Tourangeau G. The 5As: a practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine. 2016;34(8):1018–24. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.065 PMID: 26672676.

- Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Zhou C, Catz S, Myaing M, Mangione-Smith R. The relationship between parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey scores and future child immunization status: a validation study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(11):1065–71. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2483. PMID: 24061681.

- Gilkey MB, Reiter PL, Magnus BE, A-L M, Dempsey AF, Brewer NT. Validation of the vaccination confidence scale: a brief measure to identify parents at risk for refusing adolescent vaccines. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(1):42–9. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2015.06.007. PMID: 26300368.

- Machida M, Nakamura I, Kojima T, Saito R, Nakaya T, Hanibuchi T, Takamiya T, Odagiri Y, Fukushima N, Kikuchi H. et al. Trends in COVID-19 vaccination intent from pre- to post-COVID-19 vaccine distribution and their associations with the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination by sex and age in Japan. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(11):11, 3954–3962. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1968217.

- Adamu AA, Essoh TA, Adeyanju GC, Jalo RI, Saleh Y, Aplogan A, Wiysonge CS. Drivers of hesitancy towards recommended childhood vaccines in African settings: a scoping review of literature from Kenya, Malawi and Ethiopia. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021 May. 20(5):611–21. doi:10.1080/14760584.2021.1899819.

- Abdou M, Kheirallah M, Aly. Ramadan, A., Elhadi, Y.A.M., Elbarazi, I., Deghidy, E.A., El Saeh, H.M., Salem, K.M. and Ghazy, R.M. Psychological antecedents towards COVID-19 vaccination using the Arabic 5C validated tool: An online study in 13 Arab countries. MedRxiv. 2021. 08.31.21262917. doi: 10.1101/2021.08.31.21262917.

- Hossain BM, Alam Z, Islam S, Shafayat S, Faysal M, Rima S, Hossain A, Mamun AA. Health belief model, theory of planned behavior, or psychological antecedents: what predicts COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy better among the Bangladeshi adults? Front Public Health. 2021;9:1172. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.711066.

- Saini M, and Shlonsky A. Methods for aggregating, integrating, and interpreting qualitative research’, systematic synthesis of qualitative research, pocket guides to social work research methods. online edn. Oxford Academic; 2012. 2012 May 24 [accessed 2022 Aug 5]. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195387216.003.0002.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Guide to qualitative evidence synthesis: evidence-informed policymaking using research in the EVIPNET framework. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Adeyanju GC, Augustine TM, Volkmann S, Oyebamiji UA, Ran S, Osobajo OA, Otitoju A. Effectiveness of intervention on behaviour change against use of non-biodegradable plastic bags: a systematic review. Discov Sustain. 2021c;2(1):13. doi:10.1007/s43621-021-00015-0.

- German institute for global and area studies challenging trust in government: COVID in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2021;3:1862–3603. https://www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus/challenging-trust-in-government-covid-in-sub-saharan-africa.

- Light DW. Exaggerating the benefits of the ‘decade of vaccines’. Health Aff. 2011;30(10):2026. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0969.