ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 booster dose is considered an important adjunct for the control of the COVID-19 pandemic due to reports of reduced immunity in fully vaccinated individuals. The aims of this study were to assess healthcare workers’ intention to receive the booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine and to identify predictive factors among healthcare workers. A cross-sectional study was conducted among healthcare workers selected in two provinces, Kasai Oriental, and Haut-Lomami. Data were collected using a questionnaire administered through structured face-to-face interviews, with respondents using a pre-tested questionnaire set up on the Open Data Kit (ODK Collect). All data were analyzed using SPSS v26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Vaccination coverage for COVID-19, considering declarations by health workers, is around 85.9% for the province of Kasai Oriental and 85.8% for Haut-Lomami. A total of 975 responses were collected, 71.4% of health workers at Kasai Oriental and 66.4% from Haut-Lomami declared a definite willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster. The duration of protection was the main reason for accepting a booster COVID-19 dose for 64.6% of the respondents. Logistic regression analysis showed that having chronic diseases (aOR = 2.95 [1.65–5.28]), having already received one of the COVID-19 vaccines (aOR = 2.72 [1.43–5. 19]); the belief that only high-risk individuals, such as healthcare professionals and elderly people suffering from other illnesses, needed a booster dose (aOR = 1.75 [1.10–2.81]). Considering the burden of COVID-19, a high acceptance rate for booster doses could be essential to control the pandemic. Our results are novel and could help policymakers design and implement specific COVID-19 vaccination programs to reduce reluctance to seek booster vaccination.

Introduction

Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) is one of the most serious public health challenges of this century. Two years after its emergence, the rapid development and deployment of effective vaccines against COVID-19 contributed to bringing the pandemic under control, significantly reducing the risk of severe disease and death associated with COVID-19.Citation1 Vaccines to prevent coronavirus infection are considered the most promising approach to mitigating the pandemic and preventing serious SARS-CoV-2 infections.Citation2

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are a priority population group for vaccination against COVID-19. As a high-risk population, HCWs have been prioritized as one of the first groups to receive the vaccine according to the recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices (ACIP).Citation3,Citation4 In many countries, HCWs remain an important source of medical information and role models for the general population. Therefore, reluctance to vaccinate among HCWs can have widespread negative ramifications.Citation5,Citation6

The development of effective vaccines against COVID-19 has represented a significant advance in the fight against the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Vaccines have been shown to provide short-term protection against the major adverse health outcomes of hospitalization and death.Citation7,Citation8 However, protection against breakthroughs is waning and breakthroughs have been widely documented.Citation9 In response, the Food and Drug Administration advisory committee recommended a booster dose of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines at least 5 months after completion of the primary series for persons aged 12 years and older and 18 years and older, respectively. A booster dose of Johnson & Johnson/Janssen vaccine was authorized more quickly, as early as 2 months after the single dose to persons aged 18 years and older.Citation8,Citation10

In February 2021, the DRC’s National Technical Advisory Group on Vaccination (GTCV) issued recommendations for the use of COVID-19 vaccines in the DRC, as well as vaccination strategies and priority target populations for vaccination, in line with the recommendations of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Vaccination, as well as major efforts in risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) around vaccination. The three priority target groups for phase 1, estimated at 20% of the population, were health and social workers, the over 55 s and people with co-morbidities. The DRC government had planned two sub-phases for phase 1, based on the country’s projected vaccine allocations. Sub-phase 1a was to cover 3% of the population, and sub-phase 1b 17%, in order to achieve vaccination coverage of 20% of the most at-risk population.Citation11

By March 2021, 1.8 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine had been received in the DRC, and COVID-19 vaccination officially began on April 19, 2022. The first vaccine to be introduced by the DRC was the COVID-19 vaccine ChAdOx1-S [recombinant] (AstraZeneca®/Covishield), administered as a two-dose schedule. Since the start in September 2021 it should be noted that Moderna mRNA-1273 is the first two-dose COVID-19 vaccine to be administered throughout the DRC as a primary series of vaccination against COVID-19.Citation11

Vaccination protects against disease, by stimulating the immune system to produce antibodies without causing infection. Widge et al. found that people vaccinated against COVID-19 had higher levels of antibodies against COVID-19 (17 weeks after the first vaccination) than those recovered from COVID-19 infection with a median of 34 days since diagnosis (range 23 to 54).Citation12 However, over time, the levels of antibodies that develop in response to vaccines decline, and COVID-19 vaccines are no exception.Citation13 In a recent study, Mizrahi et al. also found that protection against infection and disease gradually declines over time.Citation14

It is therefore extremely important and crucial to understand and assess the willingness of healthcare workers to receive the second booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine; no literature is available on this subject. The objectives of our study were to assess healthcare workers’ intention to receive the booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine and to identify predictive factors among healthcare workers.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted in the Democratic Republic of Congo in two provinces, namely Kasai Oriental and Haut-Lomami. These were chosen on the basis of their COVID-19 vaccination coverage, one with high coverage (Kasai Oriental) and one with low coverage (Haut-Lomami). Data were collected in each province using a convenience sampling method between 01 April and 15 May 2023 including all healthcare workers who gave their consent to participate in the study and who were present on the day of the survey. Information was collected from a sample of healthcare workers in both provinces. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Healthcare workers (HCWs), aged 18 or older, defined as anyone who directly or indirectly provides care or services to patients,Citation15 currently employed as HCWs in hospitals and with the language skills to participate in the survey and individuals who expressed interest in participating in the study. Subjects with a history of mental illness or who did not give consent were excluded from participation in the study.

The Cochrane formula,Citation15 where n is the minimum sample size, Z is the normal standard deviation corresponding to a significance level of 5% and p is the proportion of HCWs who intended to receive the booster dose of COVID-19 when offered in the DRC, was used to estimate the target sample size per province.

As we did not find a reference study on intention to receive the booster dose in the DRC at the time of study design, we estimated that 50% of HCWs would intend to receive the booster dose, d = tolerable margin error set at 0.05; therefore, Z = 1.96. A confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5% were used. A confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5% were used, resulting in a minimum sample of 484 participants per province, after allowing for non-response, per province, after allowing for non-response or 10% incomplete responses.

Study procedure

Data were collected using a questionnaire administered through structured face-to-face interviews, with respondents using a pre-tested questionnaire set up on the Open Data Kit (ODK Collect). Participants were asked to provide informed consent before being included in the study.

Measures

The questionnaire was developed on the basis of previous studies.Citation16,Citation17 It was divided into four sections: (1) information on socio-demographic characteristics, (2) their intention to receive the booster dose; (3) their perception of the booster dose and (4) general knowledge about COVID-19 and the booster dose. A pilot study was conducted in a small group of participants (n = 50) to get their ideas on simplifying and shortening the questionnaire. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the internal consistency reliability of the questionnaire was 0.89.

Ethical approval

All health workers were informed of the objectives of the study and agreed to and signed a consent form prior to participation. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Lubumbashi (approval letter No. UNILU/CEM/226/2023) in DRC.

Statistical analyses

Categorical data related to demographic variables are presented as frequencies and proportions. Associations between the independent variables and the primary endpoints (acceptance and intention to receive the COVID-19 booster dose) were tested using the t-test or chi-square test, as appropriate. A stepwise ascending Wald analysis was performed to define the variables to be included in the final logistic regression model, based on the results of the univariate models, and was complemented by an analysis of the predictive power of the model using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. In this study, the adjusted odds ratio was calculated using a 95% confidence interval. IBM-SPSS version 26 statistical software (BM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the analysis.

Results

The demographic information of participants is depicted in . It can be seen that 58.3% of participants were male, 94.6% between the ages of 18 and 55, 66.3% were married, while 1.1% were divorced.; the majority of participants were Christian (91,)%); 40.3% were nurses, 14.2% administrative staff and 13.3% doctors. In terms of working experience, 42.4% were less than 5 years old and 38.2% between 5 and 10 years. A statistically significant difference was observed between the two provinces with regard to the marital status and profession of healthcare workers.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants by province.

shows that 19.7% of the participants had a chronic disease, including 41.7% with hypertension, 37.5% with diabetes and 2.6% with acute or chronic renal failure. More than eight-tenths (85.8%) reported having received the COVID-19 vaccine, of which 75.7% had received one dose and 24.3% two doses. Regarding the type of vaccine against COVID-19 received, 82.2% said they had taken Johnson and Johnson, 19.0% AstraZeneca vaccine, 6.3% sinovac, and 1.3% moderna vaccine. It should be noted that 96.0% of the participants in the province of Kasai Oriental had received a single dose of vaccine, compared with 56.3% in the province of Haut-Lomami. As for the second dose, 43.7% of staff in Haut-Lomami had received it, compared with 4.0% in Kasai Oriental. This difference is statistically significant (p = .000).

Table 2. Participant’s health, COVID-19 vaccination status and type of vaccine against COVID-19 received by province.

A statistically significant difference was found for the type of vaccine, as 89.6% of the participants in Kasai Oriental had taken the Johnson and Johnson vaccine, compared with 75.5% in Haut-Lomami.

shows that 74.8% of health workers in the province of Kasai Oriental knew that a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine should be administered in the DRC, compared with 62.1% in the province of Haut-Lomami, and this difference is statistically significant (p = .000). In sum, 68.1% of health workers knew that a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine should be administered in the DRC. Concerning the intention to take the booster dose, 71.4% of health workers in Kasai Oriental and 66.4% agreed, but this difference was not statistically significant (p = .12). Thus, a total of 68.9% intended to take the booster dose in the two provinces.

Table 3. Willingness and reasons for being or not willing to take a COVID-19 booster-dose vaccine by province.

Among the reasons influencing willingness to take the booster dose were the duration of protection (64.6%), employer requirements (5.8%), government policy (8.8%) and suggestions from friends or family members (1.6%), the booster dose can prevent serious infections (7.9%) and the booster dose reinforces the effect of the first dose (11.3%). Statistically significant differences in favor of certain reasons for accepting the booster dose were noted in both provinces. These were, in particular, the duration of protection (p = .0002), the employer’s requirement (p = .009), the fact that the booster dose can prevent serious infections (p = .004) and the fact that the booster dose reinforces the effect of the first dose (p = .0003).

The main reasons why participants are not willing or confident to receive a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, 52.8% think that the single dose of COVID-19 vaccine is already sufficient and a second dose is not necessary, 29.8% talk about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine is unclear, 19.1% about the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine is unclear, 21.5% believe that they are healthy enough to fight COVID-19, 5.9% also believe that COVID-19 in the DRC is under control and there is no need to vaccinate, 8.9% are concerned about possible long-term side effects and 11.2% are against vaccines in general. No statistically significant difference was noted in both provinces.

shows that professional category (doctor) (OR: 1.59[1.03–2.45]) and working experience less than 5 years (OR: 1.56[1.09–2.25]) were significantly associated to willingness for the booster dose

Table 4. Association between socio-demographic factors and willingness to receive the booster dose.

shows that having a chronic disease, having received a dose of vaccine against COVID-19, knowing that the booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine is planned in the DRC and the other perceptions are significantly associated to willingness for the booster dose.

Table 5. Association between participant’s health, perception about COVID-19 booster dose and willingness to receive the booster dose.

details the different characteristics that influenced the willingness of HCWs to take the booster dose, in particular having chronic diseases, having already received one of the COVID-19 vaccines, knowing that the dose of the COVID-19 vaccine is planned in the DRC or that the booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine is essential for the DRC, the fact that to think that if all members of society maintain preventive measures, the COVID-19 pandemic can be eradicated without vaccination, the belief that pharmaceutical companies have developed safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines, the belief that only people at high risk, such as healthcare workers and the elderly suffering from other diseases, need a booster dose. It should also be noted that believing that people who receive the COVID-19 vaccine are more likely to contract serious illness, saying that it is good for the health of the family to receive the booster dose.

Table 6. Logistic regression analysis exploring factors associated with willingness to take the COVID-19 booster vaccine.

The fact that a health worker recommends receiving a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and if the family recommends me to receive the booster dose of the COVD-19 vaccine, I will choose to do so were explanatory factors for willingness to receive the booster dose.

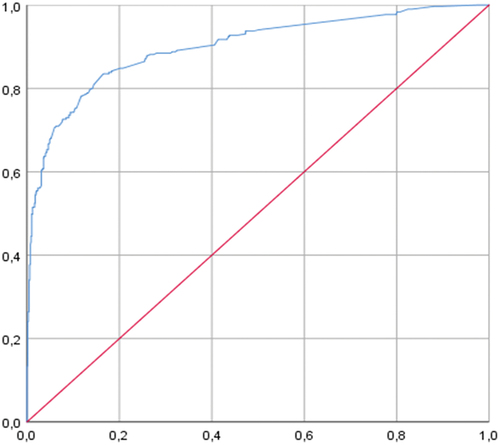

The area under the curve (AUC) values in indicate an ability to predict healthcare workers’ intention to receive the booster dose of around 89.9% (AUC between 87.6 and 92.2).

The Area Under the Curve (AUC) can be interpreted as the probability that in the case of this study is 89.9%, among two randomly selected subjects, one intending to receive the booster dose and one not intending to receive the booster dose, the marker value is higher for the person intending to receive the booster dose than for the person not intending to receive the booster dose ().

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report willingness to receive the booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine in DRC. The objectives of this study were to determine the uptake of the COVID-19 booster dose and the reasons for taking or not taking it and to identify the predictive factors among healthcare workers.

In this study, 68.9% of the participants were willing to receive a COVID-19 booster vaccine, and 31.1% were not. The prevalence of this will was higher than the values observed among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia (55.3%).Citation18 Surprisingly, this value was also considerably lower than that of the general population in India (59.1%),Citation19 in the Middle East and North Africa region (60.2%),Citation20 but lower than the values observed in the Czech Republic (71.3%)Citation21 and China (87%)Citation22., China (91.1%),Citation23 Japan (97.8%),Citation24 students and university staff in Italy (85.7%)Citation25 and the USA (96.2%).Citation26

Willingness to accept the booster may vary from one country to another and even within the same country. But in our context, no difference between the two provinces was observed in our study. In our study, we found that 68.9% of healthcare workers were willing to receive the COVID-19 booster dose but quite a few HCWs (31.1%) were still hesitant. The rate of acceptance identified in this study is not far from the reported rate of 64% in Saudi Arabia.Citation17 The rates recorded in RDC are consistent with the low willingness rates in developing countries such as Saudi Arabia (55.3%), Algeria (51.6%) and Ghana (46.2%).Citation18,Citation27,Citation28 Globally, acceptance of the booster dose of COVID-19 vaccines is generally higher in developed countries than in developed countries. Available data showed rates of 79.1% and 83.6% among adults and healthcare workers (HCW) in the United States,Citation29,Citation30 71 .3% among HCWs in the Czech Republic,Citation21 84.5% among medical students in Japan.Citation31 The heterogeneity of willingness to accept the booster dose can be explained by several factors. People in developing countries are more likely to receive the booster dose because of their high level of trust in the government, employer recommendations, access to COVID-19 and knowledge about vaccines, high sensitivity and good risk perception. Additionally, healthcare workers’ desire for COVID-19 vaccines could be attributed to several factors, such as uneven medical histories, different levels of knowledge about science, and different awareness of the importance of vaccination.Citation32

Our results indicate that duration of protection (64.6%), reinforcement of the effect of the first dose (11.3%), employer requirements (5.8%) and government policy (8.8%) were major factors influencing the public’s willingness to be vaccinated with a booster dose. These findings are consistent with other research studies.Citation33

We describe the factors linked to vaccinations after a pandemic period of almost 2 years in the DRC, when the vaccination program was accessible to all.

Among the other reasons given by some healthcare workers, 11.3% said that the booster dose reinforced the effect of the first dose. There is evidence of a decline in immunity to SARS-Co-V-2 after a few months of receiving the second dose of vaccine in Israel.Citation34 Recent analyses have suggested that a booster dose of BNT162b2 vaccine reduces the rates of confirmed infection and severe disease associated with COVID-19. The rate of confirmed infection was significantly lower than in the no-booster group. There is evidence of waning immunity to SARS-Co-V-2 a few months after receiving the second dose of vaccine in Israel. Furthermore, in a study by Arbel et al., participants who received a booster dose of BNT162b2 at least 5 months after the second dose had COVID-90 mortality rates 19% lower than those who did not receive a booster dose of the vaccine.Citation35

The presence of comorbidities or chronic illnesses is a predictor of vaccine acceptance. Our study showed that healthcare workers with chronic diseases were three times more likely to receive the booster dose. This contradicts a previous finding that participants with chronic conditions are significantly less likely to accept the booster dose than healthy individuals.Citation36 COVID-19 patients with underlying diseases, such as hypertension, cancer, cardiovascular disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes and chronic kidney disease, have a significantly higher risk of mortality when they contract the disease,Citation37 making it crucial for this population to receive the vaccine as soon as possible. They should therefore be given priority, and efforts redoubled to raise awareness among populations with chronic diseases of the seriousness and implications of COVID-19, and how the vaccine can mitigate them. According to Piotr Rzymski,Citation38 it is important to note that the majority of individuals representing high-risk groups for COVID-19, including the elderly, obese, and those with chronic conditions such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, or heart disease this should improve their overall situation during the COVID-19 chronic kidney disease pandemic, are prepared to receive a booster dose, and will likely follow updated guidance on COVID-19 vaccination strategies.Citation39

In the multivariate regression, we also found that having already received one of the COVID-19 vaccines was a predictive factor of willingness to take the booster vaccine. This corroborates the results of research in the literature.Citation39,Citation40 Studies conducted in ChinaCitation41 and Hong Kong showed that people who had already taken the influenza vaccine were more willing to take the COVID-19 vaccine. This is probably due to previous positive experiences of receiving a vaccine. Lai et al., reported that the increased odds of booster acceptance were associated with previous COVID-19 vaccination.Citation42

Strengths

One of the key benefits of this study is its ability to provide health policy-makers and stakeholders with evidence-based planning for booster-dose promotion. A rigorous health intervention involving key messages delivered by vaccine policy-makers would provide a better understanding of the factors contributing to acceptance of booster vaccines and reluctance to administer them.

Consequently, the results of this study may help to overcome barriers and propagate factors facilitating the nationwide rollout of booster vaccines while improving public commitment to booster vaccines. The results of this study could provide scientific evidence for further observational studies of COVID-19

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, the participants in the study were recruited using a nonrandom sampling method, which may affect the external validity of this study and its generalizability. Second, our study is susceptible to self-reporting bias because we asked HCWs to describe their attitude and practices about the COVID-19 vaccines rather than objectively measuring them.

Conclusion

Despite the clear willingness of 68.1% of healthcare workers to receive a booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine, a percentage of reluctance to receive the booster dose may pose a threat to the effectiveness of the prevention and control of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study identified the determinants of individual intention to receive a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. There are a series of factors that predict intention to receive a booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine. There are a series of factors that predict intention to receive a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, including having chronic illnesses, having already received one of the COVID-19 vaccines, the fact that another HCWs recommends receiving a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. The public health communication message must therefore be specifically adapted to respond to the factors identified as being associated with willingness to receive the COVID-19 booster vaccine.

These results support recommendations that all healthcare workers receive booster doses. Targeted strategies are needed to improve the acceptability of the booster dose among healthcare workers. These strategies should include educating healthcare providers and encouraging all to receive a booster dose when eligible, regardless of age and prior COVID-19 infection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chi WY, Li Y-D, Huang H-C, Chan TEH, Chow S-Y, Su J-H, Ferrall L, Hung C-F, Wu T-C. COVID-19 vaccine update: vaccine effectiveness, SARS-CoV-2 variants, boosters, adverse effects, and immune correlates of protection. J Biomed Sci. 2022;29(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12929-022-00853-8.

- Wong LP, Alias H, Siaw Y-L, Muslimin M, Lai LL, Lin Y, Hu Z. Intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster dose and associated factors in Malaysia. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(5). doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2078634.

- A S, Mohsina Haq NUH, Rehman A, Haq M, Haq H, Rajab H, Ahmad J, Ahmed J, Anwar S. Identifying higher risk subgroups of health care workers for priority vaccination against COVID-19. Ther Adv Vaccines. 2022;10:1–7. doi:10.1177/25151355221080724.

- Shui X, Wang F, Li L, Liang Q. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among healthcare workers in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2022;17(8 August):73–83. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0273112.

- Desye B. Prevalence and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among healthcare workers: a systematic review. Front Public Health. 2021;10(September):1–7. 2022. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.941206.

- Adane M, Ademas A, Kloos H. Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of COVID-19 vaccine and refusal to receive COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers in northeastern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1–14. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-12362-8.

- Pooley N, Abdool Karim SS, Combadière B, Ooi EE, Harris RC, El Guerche Seblain C, Kisomi M, Shaikh N. Durability of vaccine-induced and natural immunity against COVID-19: a narrative review. Infect Dis Ther. 2023;12(2):367–87. doi:10.1007/s40121-022-00753-2.

- Townsend JP, Hassler HB, Sah P, Galvani AP, Dornburg A. The durability of natural infection and vaccine-induced immunity against future infection by SARS-CoV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119(31):1–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.2204336119.

- Feikin DR, Higdon MM, Abu-Raddad LJ, Andrews N, Araos R, Goldberg Y, Groome MJ, Huppert A, O’Brien KL, Smith PG. et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet. 2022;399(10328):924–44. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00152-0.

- Adams K, Rhoads, JP, Surie D, Gaglani M, Ginde, AA, McNeal T, Talbot, HK, Casey, JD, Zepeski A, Shapiro, NI. et al. Vaccine effectiveness of primary series and booster doses against COVID-19 associated hospital admissions in the United States: Living test negative design study. BMJ. 2022;11:1–15. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-072065.

- Zola Matuvanga T, Doshi RH, Muya A, Cikomola A, Milabyo A, Nasaka P, Mitashi P, Muhindo-Mavoko H, Ahuka S, Nzaji M. et al. Challenges to COVID-19 vaccine introduction in the Democratic Republic of the Congo–a commentary. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(6). doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2127272.

- Malhotra S, Mani K, Lodha R, Bakhshi S, Mathur VP, Gupta P, Kedia S, Sankar J, Kumar P, Kumar A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 reinfection rate and estimated effectiveness of the inactivated whole virion vaccine BBV152 against reinfection among health care workers in New Delhi, India. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):1–14. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42210.

- Ward H, Whitaker M, Flower B, Tang SN, Atchison C, Darzi A, Donnelly CA, Cann A, Diggle PJ, Ashby D. et al. Population antibody responses following COVID-19 vaccination in 212,102 individuals. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1–6. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28527-x.

- Mizrahi B, Lotan R, Kalkstein N, Peretz A, Perez G, Ben-Tov A, Chodick G, Gazit S, Patalon T. Correlation of SARS-CoV-2-breakthrough infections to time-from-vaccine. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1–5. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26672-3.

- Charan J, Biswas T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35(2):121–6. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.116232.

- Delwer M, Hawlader H, Lutfor M, Nazir A. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in South Asia: a multi-country study. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;114:1–0.

- Vellappally S, Naik S, Alsadon O, Al-Kheraif AA, Alayadi H, Alsiwat AJ, Kumar A, Hashem M, Varghese N, Thomas NG. et al. Perception of COVID-19 booster dose vaccine among healthcare workers in India and Saudi Arabia. Int J Environl Res Public Health. 2022;19(15):1–11. doi:10.3390/ijerph19158942.

- Alhasan K, Aljamaan F, Temsah, MH, Alshahrani F, Bassrawi R, Alhaboob A, Assiri R, Alenezi S, Alaraj A, Alhomoudi, RI. et al. Covid-19 delta variant: Perceptions, worries, and vaccine-booster acceptability among healthcare workers. Healthcare. 2021;9(11):1–19. doi:10.3390/healthcare9111566.

- Achrekar GC, Batra K, Urankar Y, Batra R, Iqbal N, Choudhury SA, Hooda D, Khan R, Arora S, Singh A. et al. Assessing COVID-19 booster hesitancy and its correlates: an early evidence from India. Nato Adv Sci Inst Se. 2022;10(7):1–13. doi:10.3390/vaccines10071048.

- Abouzid M, Ahmed AA, El-Sherif DM, Alonazi WB, Eatmann AI, Alshehri MM, Saleh RN, Ahmed MH, Aziz IA, Abdelslam AE. et al. Attitudes toward receiving COVID-19 booster dose in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: a cross-sectional study of 3041 fully vaccinated participants. Nato Adv Sci Inst Se. 2022;10(8):1270. doi:10.3390/vaccines10081270.

- Klugar M, Riad A, Mohanan L, Pokorná A. COVID-19 vaccine booster hesitancy (VBH) of healthcare workers in czechia: national cross-sectional study. Nato Adv Sci Inst Se. 2021;9(12):1–29. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121437.

- Luo C, Chen HX, Tung TH. COVID-19 vaccination in China: adverse effects and its impact on health care working decisions on booster dose. Nato Adv Sci Inst Se. 2022;10(8):1–11. doi:10.3390/vaccines10081229.

- Tung TH, Lin XQ, Chen Y, Zhang MX, Zhu JS. Willingness-to-pay for a booster dose of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in Taizhou, China. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(6):1–7. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2014731.

- Yoshida M, Kobashi Y, Kawamura T, Shimazu Y, Nishikawa Y, Omata F, Zhao T, Yamamoto C, Kaneko Y, Nakayama A. et al. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine booster hesitancy: a retrospective cohort study, fukushima vaccination community survey. Nato Adv Sci Inst Se. 2022;10(4):4–11. doi:10.3390/vaccines10040515.

- Folcarelli L, Del Giudice GM, Corea F, Angelillo IF. Intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine booster dose in a university community in Italy. Nato Adv Sci Inst Se. 2022;10(2):1–11. doi:10.3390/vaccines10020146.

- Lee RC, Hu H, Kawaguchi ES, Kim AE, Soto DW, Shanker K, Klausner JD, Van Orman S, Unger JB. COVID-19 booster vaccine attitudes and behaviors among university students and staff in the United States: The USC trojan pandemic research initiative. Prev Med Rep. 2022;28(June):101866. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101866.

- Storph RP, Essuman MA, Duku‐Takyi R, Akotua A, Asante S, Armah R, Donkoh IE, Addo PA. Willingness to receive COVID-19 booster dose and its associated factors in Ghana: A cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6(4). doi:10.1002/hsr2.1203.

- Lounis M, Bencherit D, Rais MA, Riad A. COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Hesitancy (VBH) and its drivers in Algeria: national cross-sectional survey-based study. Nato Adv Sci Inst Se. 2022;10(4):1–14. doi:10.3390/vaccines10040621.

- Yadete T, Batra K, Netski DM, Antonio S, Patros MJ, Bester JC. Assessing acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine booster dose among adult americans: A cross-sectional study. Nato Adv Sci Inst Se. 2021;9(12):1424. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121424.

- Pal S, Shekhar R, Kottewar S, Upadhyay S, Singh M, and Pathak D, “Pal S, Shekhar R, Kottewar S, Upadhyay S, Singh M, Pathak D. et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and attitude toward booster doses among US healthcare workers. Vaccines. 2021 Nov 19;9(11):1358. Mdpi, pp. 1–11, 2021.10.3390/vaccines9111358.

- Sugawara N, Yasui-Furukori N, Fukushima A, Shimoda K. Attitudes of medical students toward COVID-19 vaccination: Who is willing to receive a third dose of the vaccine? Vaccines. 2021;9(11):1–0. doi:10.3390/vaccines9111295.

- Lubad MA, Abu-Helalah MA, Alahmad IF, Al-Tamimi MM, QawaQzeh MS, Al-Kharabsheh AM, Alzoubi H, Alnawafleh AH, Kheirallah KA. Willingness of healthcare workers to recommend or receive a third COVID-19 vaccine dose: a cross-sectional study from Jordan. Infect Dis Rep. 2023;15(2):210–21. doi:10.3390/idr15020022.

- Tao C, Lim X, Chew C, Rajan P, Chan H. Preferences and willingness of accepting COVID-19 vaccine booster: Results from a middle-income country. Vaccine. 2020;40(January):7515–7519.

- Bar-On YM, Goldberg Y, Mandel M, Bodenheimer O, Freedman L, Kalkstein N, Mizrahi B, Alroy-Preis S, Ash N, Milo R. et al. Protection of BNT162b2 vaccine booster against Covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(15):1393–400. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2114255.

- Arbel R, Hammerman A, Sergienko R, Friger M, Peretz A, Netzer D, Yaron S. BNT162b2 vaccine booster and mortality due to Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(26):2413–20. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2115624.

- Mohamed NA, Solehan HM, Dzulkhairi M, Rani M. Knowledge, acceptance and perception on COVID-19 vaccine among Malaysians: A web- based survey. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(8):1–17. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0256110.

- Ssentongo ESH, Paddy AES, Ba DM. Association of cardiovascular disease and 10 other pre-existing comorbidities with COVID-19 mortality: A systematic review and meta- analysis. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;15(8):1–16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0238215.

- Rzymski P, Poniedziałek B, Fal A. Willingness to receive the booster covid‐19 vaccine dose in poland. Nato Adv Sci Inst Se. 2021;9(11):1–14. doi:10.3390/vaccines9111286.

- Chan EY, Cheng CK, Tam GC, Huang Z, Lee PY. Willingness of future A/H7N9 influenza vaccine uptake: A cross-sectional study of Hong Kong community. Vaccine. 2015;33(38):4737–40. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.046.

- Banik R, Rahman M, Sikder MT, Rahman QM, Pranta MUR. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the COVID-19 pandemic among Bangladeshi youth: a web-based cross-sectional analysis. J Public Heal Theory Pract. 2021;31(1):9–19. doi:10.1007/s10389-020-01432-7.

- Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines MDPI. 2020;8(482):1–14. doi:10.3390/vaccines8030482.

- Lai X, Zhu H, Wang J, Huang Y, Jing R, Lyu Y, Zhang H, Feng H, Guo J, Fang H. et al. Public perceptions and acceptance of COVID-19 booster vaccination in China: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines MDPI. 2021;9(1461):1–17. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121461.