ABSTRACT

Vaccine literacy (VL) is an important part of health literacy (HL), which is of great significance in reducing vaccine hesitancy and improving vaccine coverage rate. We aimed to perform a bibliometric analysis of VL research conducted from 1982 to 2023 to evaluate its current status and prospects. All relevant publications were retrieved from the Web of Science Core Collection database and the Scopus database. The Bibliometrix R-package and VOSviewer software were used to analyze the publication outputs, countries, organizations, authors, journals, cited publications, and keywords. In total, 1,612 publications were included. The number of articles published on VL generally showed an increasing trend. The United States was in a leading position among all countries and had the closest connections with other countries and organizations. Its in-depth study of vaccine hesitancy provided a good foundation for VL research. Harvard University was the most productive organization. Bonaccorsi G was the most productive and cited author. VACCINES was the most productive journal. Research topics primarily revolved around vaccination, HL, vaccine hesitancy, and COVID-19 vaccine. In conclusion, the current research on the conceptual connotation and influencing factors of VL is insufficiently deep and should be further improved in the future to distinguish it from HL in a deeper manner. More tools for measuring VL need to be developed, such as those applicable to different populations and vaccines. The more complex relationship between VL, vaccine hesitancy and vaccination needs to be further explored. Gender differences deserve further investigation.

Introduction

The development and application of vaccines are among the greatest achievements in public health. Expanding vaccination coverage is a cost-effective way to improve global welfare and control the increase in infectious diseases.Citation1 However, the lack of confidence in vaccines has resulted in vaccine hesitancy.Citation2 According to MacDonald, “Vaccine hesitancy refers to delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services. Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context specific, varying across time, place and vaccines.”Citation3 Vaccine hesitancy was listed by the World Health Organization as one of the top 10 threats to global health in 2019.Citation4 To address the issues associated with vaccine hesitancy, the concept of “vaccine literacy” (VL) has been proposed.Citation5

VL is an important component of health literacy (HL).Citation6 The term “vaccine literacy” was first proposed by MacDonald et al.,Citation7 but the concept was first elaborated on by Ratzan in 2011, “VL is not simply knowledge about vaccines, but also developing a system with decreased complexity to communicate and offer vaccines as a necessity for a functioning health system.”Citation8 VL was subsequently defined by Biasio LR,Citation9 Michel,Citation10 Chiara Lorini,Citation11 and others (Table S1). Several studies have highlighted the crucial role of VL in addressing vaccine hesitancy and improving vaccination rates. For instance, Sirikalyanpaiboon et al. found an inverse relationship between VL and vaccine hesitancy.Citation12 Similarly, Badua et al. argued that the defining attributes of VL include health literacy, disease prevention, education, and immunization, emphasizing its role in not only understanding vaccines but also in facilitating individual engagement with vaccination efforts.Citation6 Furthermore, research has shown that VL serves as an important internal motivator for individuals to select vaccines, overcome hesitancy, and ultimately enhance vaccination rates.Citation13

In addition, researchers have explored tools for measuring VL (Table S2). VL measuring tools are insufficient and are derived from HL measuring tools.Citation14 Recently, most studies on VL use the Health Literacy about Vaccination in Adulthood in Italian (HLVa-IT), developed by Biasio et al., to measure VL levels. This scale can comprehensively evaluate functional, interactive, and critical vaccine literacy.Citation15 Its applicability was validated in different socio-cultural contexts such as China,Citation16 Thailand,Citation17 Turkey,Citation18 and Spain.Citation19 Subsequently, Biasio et al. developed the COVID-19 VL scale based on the HLVa-IT, which aims to measure whether adults can acquire, understand, and evaluate information about the COVID-19 vaccine.Citation20,Citation21 In addition, HLS19-VAC, revised from the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q47), contains four items that can be used to measure vaccine literacy levels.Citation22 Various countries have also conducted studies measuring VL levels in adults,Citation20–25 parents of children,Citation26–29 and diseased populations.Citation19

Scholars have conducted research in the field of vaccine literacy, mainly involving the conceptual connotations of VL and measuring tools to assess the level of VL in various populations. The importance of VL has gradually become prominent, and its improvement is urgently required. However, the current literature lacks a review of research progress on VL and an analysis of research trends. VL is not only related to individuals but also to social, economic, political, and other factors.Citation11,Citation22 To comprehensively understand the progress and trends of VL research, and to provide guidance for future prevention interventions, it is necessary to perform a bibliometric analysis.

This study aimed to perform a bibliometric and visual analysis of VL research from 1982 to 2023 to clarify research trends over the past 42 years, and analyze the research status in VL research. Through this study, we hope to provide a reference for improving VL, reducing vaccine hesitancy, and improving vaccination coverage, and provide new perspectives and ideas for future research on VL.

Methods

Data sources

The Web of Science (WoS) database has high quality standards and the wider literature coverage.Citation30,Citation31 Scopus is the largest abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed literature.Citation32 Based on their authority and comprehensiveness, we selected the WoS Core Collection (WoSCC) database and Scopus database as the literature data source to search the literature in the field of VL published from 1982 (the first one was published in 1982) to 2023. The keywords “vaccine literacy,” “vaccination literacy,” “vaccination health literacy” and “vaccine health literacy” were used to search the literature. The document types were limited to reviews and articles. The language of the documents was limited to English. Duplicate and irrelevant documents were excluded. Finally, 1,612 literatures were included in the bibliometric analysis. The following information was collected: number of publications, authors, organizations, countries, keywords, journals, and number of publication citations. To avoid bias due to daily citation updates, all the above operations were performed on one day. The retrieval strategy is shown in Figure S1.

Data analysis

Bibliometric analysis provides descriptive statistics of the retrieved literature data through visualization and ranking.Citation33 Bibliometrix is scientific bibliometric software based on the R language, developed using statistical calculations and graphical R language, following the classic logical bibliometric workflow.Citation34 It is used to assess the volume and trends of a particular subject.Citation35 This study used the Bibliometrix R-package and biblioshiny package to analyze the number of annual publications, authors, journals, and documents in the field of VL from 1982 to 2023. Three-field plot was generated to show the relationships among the most productive authors, countries, and organizations. VOSviewer is a software used for visualizing and constructing bibliometric papers.Citation36 It uses web data to create maps and build networks of scientific articles, journals, scientists, research organizations, countries, and keywords.Citation37 The threshold indicates the number of occurrences. The number of variable labels displayed in the visualization map can be controlled by adjusting the threshold.Citation38 We generated a thesaurus file to exclude or consolidate similar terms, selected Full counting for the calculation, and adjusted the threshold to control the number of variable labels. VOSviewer was used to perform co-authorship analyses of countries and organizations, bibliographic coupling analyses of journals, citation analyses of the most-cited publications, and co-occurrence analyses of keywords.

Results

Publication output analysis

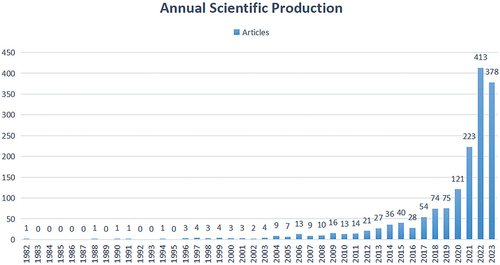

The annual publishing trends help in understanding the developmental stages of VL research.Citation39 In total, 1,612 documents related to VL were retrieved. The annual number of publications was generated using Bibliometrix. Overall, the publications showed an annual growth trend (). From 1982 to 2005, the number of publications on VL was less than 10 annually, reflecting the low level of attention paid to the topic at that time. Since then, the number of publications has increased gradually. The number of documents has grown rapidly since 2016. The number of publications exceeded 50 annually from 2017 to 2023 and more than 100 annually from 2020, illustrating the increasing attention and research on VL.

Country and organization analysis

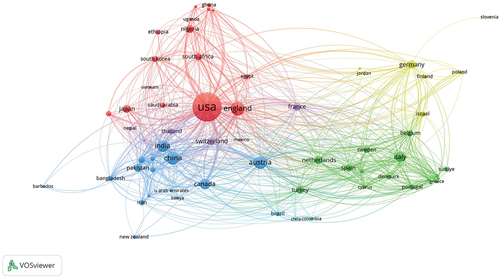

The country distribution observed in the Bibliometrix analysis helps in understanding the geographical and spatial distributions of papers (). Among the countries that published articles, the United States (n = 586, 36.35%) ranked first in terms of the number of articles published. This was followed by England (n = 131, 8.13%), China (n = 120, 7.44%), Australia (n = 117, 7.26%), and India (n = 98, 6.08%). A country’s total number of citations is an important indicator of its scientific influence on VL. The United States had the highest number of citations (18,659 citations), followed by England (4,505 citations), Canada (3,598 citations), Australia (2,415 citations), and India (1,644 citations), indicating that these countries have made large contributions to this field.

Table 1. Top 10 countries with the most publications and citations.

In the VOSviewer co-authorship analysis, the minimum number of publications per country was set to five. Of the 148 countries, 67 met this threshold. The strengths of the co-authorship links between different countries were analyzed (). The United States maintained the strongest cooperation with other countries, with a total link strength (TLS) of 318, followed by England (TLS = 237), Australia (TLS = 174), India (TLS = 147), and Germany (TLS = 115).

In total, 3,251 organizations were involved in VL research. Bibliometrix was used to analyze the 10 most productive organizations in this field (Table S3). The influential organizations included Harvard University (n = 35, 2.17%), University of California System (n = 34, 2.11%), University System of Ohio (n = 33, 2.05%), University of Toronto (n = 30, 1.86%), Emory University (n = 27, 1.67%), and University of London (n = 27, 1.67%). Of these organizations, seven were from the United States, one from Canada, one from England, and one from Australia. This indicates that the United States has made a significant contribution to VL research. Using VOSviewer to analyze the co-authorship relationships of organizations with more than 5 publications, the results were presented for 116 organizations (Figure S2). Sorted by TLS, the top five organizations were Emory University (20), Aga Khan University (19), University of Toronto (19), University of Oxford (17), and University of Maryland (16).

Author analysis

Bibliometrix analysis showed that a total of 7,164 authors were involved in areas related to VL research in this study, resulting in 1,612 papers. Of these, 89 were single-author papers and 7,075 were multi-author papers. The top 10 most productive and cited authors are listed in . Among the top 10 authors with the most publications, Bonaccorsi G ranked first with 21 articles, accounting for 1.30% of all articles, followed by Lorini C with 20 articles, accounting for 1.24%, followed by Lee HY with 13 articles, accounting for 0.81%. The two most frequently cited authors were the most productive, Bonaccorsi G (550 citations) and Lorini C (529 citations). Bonaccorsi G had the highest h-index, demonstrating his notable contributions to the field. Among the top 10 authors (Figure S3), Lee HY began to publish articles in this field in 2015, most authors began to publish articles in 2017–2018.

Table 2. Top 10 authors with the most publications and citations.

Three-field plot

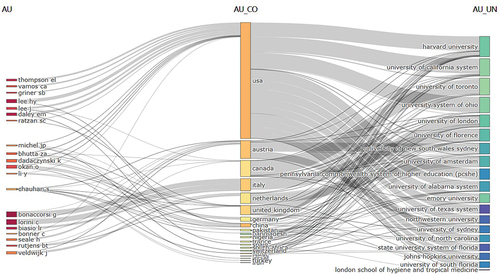

Using the Bibliometrix to map collaborations between the top 20 most productive authors (left), countries (center), and organizations (right), the rectangles of various colors in are used to depict the relevant elements in the graph. The sum of the relationships between the elements represented by the rectangle determines the height of the rectangle, with a higher rectangle representing the element with the most relationships.Citation40 The country where organizations and authors associated with vaccine literacy research worked most closely was the United States. Australia was the second-most connected country. The organization with the largest national contribution to this field was Harvard University, followed by the University of California System and the University of Toronto. Regarding authors, Bonaccorsi G, Lorini C, and Lee HY were the top three authors with the strongest collaboration in the field.

Journal analysis

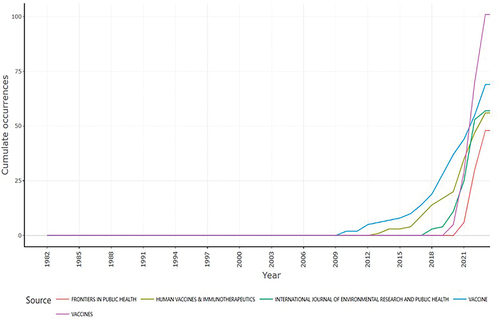

In total, 1,612 articles were published in 635 journals. To determine the core journal in a field, it was necessary to consider the frequency and number of article citations. The results of the Bibliometrix analysis (Table S4) showed that VACCINES had published the most articles, with 101 articles, followed by VACCINE (n = 69), INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH AND PUBLIC HEALTH (n = 57), HUMAN VACCINES & IMMUNOTHERAPEUTICS (n = 56) and FRONTIERS IN PUBLIC HEALTH (n = 48). HUMAN VACCINES & IMMUNOTHERAPEUTICS was the most cited (1,931 citations), followed by JOURNAL OF GENERAL INTERNAL MEDICINE (1,831 citations), and VACCINES (1,603 citations). Higher citation frequency and number of publications indicate that these journals occupy the most popular position in the field. A bibliographic coupling analysis network of the journals plotted using VOSviewer is shown in Figure S4.

The h-index refers to the maximum number of papers published in a journal that have been cited at least h times and can be used to determine the relative influence of a journal.Citation41 According to the h-index, the top five journals were VACCINES (h-index = 24), VACCINE (h-index = 23), HUMAN VACCINES & IMMUNOTHERAPEUTICS (h-index = 18), BMC PUBLIC HEALTH (h-index = 16), and INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH AND PUBLIC HEALTH (h-index = 16). VACCINE started publishing papers in this field in 2010 and VACCINES in 2020 (). Although the top five journals began publishing articles in this field at different times, the overall number of articles published showed an increasing trend. Between 2020 and 2023, the number of articles published in each journal dramatically increased.

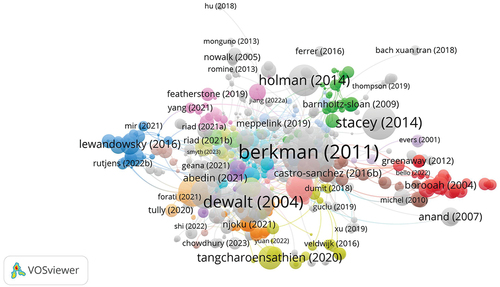

Most-cited publication analysis

An analysis of cited literature helps researchers identify research frontiers. VOSviewer was used to map the citation network of publications (). The top 10 most-cited publications in the field of VL research were analyzed using Bibliometrix (Table S5), which have high citation rates and high impact. Among them, five are reviews and five are articles. “Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review” was the most cited, with 2,688 citations, the only one cited > 2,000 times. A total of six documents exceeded 500 citations. In terms of research topics, the main concerns were health outcome, health literacy and vaccine hesitancy. From the perspective of geographical distribution, these articles mainly involved the United States, Canada, and England, indicating that these countries are in leading positions in VL research.

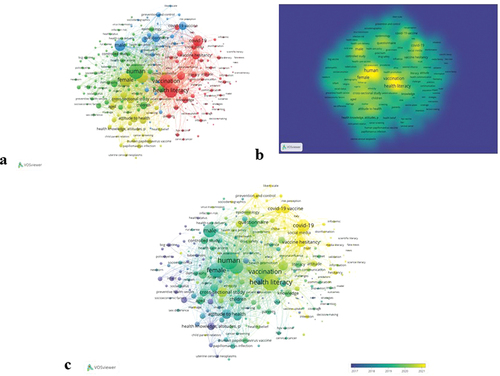

Keyword analysis

The co-occurrence network of keywords was plotted using VOSviewer (). To make the analysis of keyword clustering more comprehensive and to help researchers obtain a comprehensive view of the research topic, revealing the overall structure of the research field, as well as the complex relationships between different concepts, we chose to analyze all keywords containing the title, abstract, and author’s customization. The minimum number of keyword occurrences was set to 15. In 6,392 keywords, 4 clusters were obtained:

Figure 6. Co-occurrence analysis of keywords. The network (a), density (b), and overlay (c) visualization map of keywords of vaccine literacy research.

Cluster 1 (red): The largest node was “health literacy,” including “covid-19,” “vaccination,” “vaccine literacy,” “media,” “misinformation,” and “vaccine hesitancy.” This clustering focuses more on the relationship between people’s HL, vaccine hesitancy, vaccination and VL, and also related to the influence of the media environment and false and misinformation about vaccines on vaccination.

Cluster 2 (green): The largest node was “human,” including “vaccination coverage,” “children,” “infant,” and “child health.” This cluster focuses more on the vaccination and health status of children.

Cluster 3 (blue): This included “covid-19 vaccine,” “perception,” “influenza vaccine,” “male,” and “vaccination refusal.” This cluster focuses more on COVID-19 vaccine and influenza vaccine.

Cluster 4 (yellow): This included “female,” “human papillomavirus vaccine,” “awareness,” “uterine cervix cancer,” and “immunology.” This cluster focuses more on women’s knowledge of specific diseases and vaccines.

The density visualization map () shows that “health literacy,” “vaccination,” and “covid-19” were common keywords. The average time for keywords to appear is shown by the overlay visualization map (), with blue and yellow indicating earlier and later occurrences, respectively. Evidently, “covid-19,” “vaccine literacy” and “vaccine hesitancy” suddenly appeared in the same cluster in recent years, which also shows that with the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals’ concerns about vaccine literacy and vaccine hesitancy are increasing.

Discussion

The current study was based on data from WoSCC and Scopus, which searched 1,612 documents published in English between 1982 and 2023, involving 7,164 researchers from 3,251 organizations in 148 countries. They have published their findings in 635 journals.

Overall, the main trend was an increase in annual publications. Since 2016, the number of articles on VL has rapidly increased, possibly due to the widespread and sustained outbreaks of measles in several countries, including Italy,Citation42 the United States,Citation43 the United Kingdom,Citation44 and France,Citation45 which have led to a significant rise in related deaths globally. Scholars realized the importance of vaccination. At the same time the emergence of vaccine safety incidents, the persistence of anti-vaccination movements, and the spread of vaccine disinformation on social media platforms, have led to questions about vaccine safety and efficacy.Citation29–48 These have prompted scholars to think about VL. In particular, more than 100 publications have been published since 2021. Possibly owing to the global effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a surge in public attention and discussion on COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines.Citation21,Citation49,Citation50 Discussions about the vaccine have often been divisive, leading to a lack of confidence in a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine, the most promising intervention.Citation51 Besides, possibly the intense discussion about the COVID-19 vaccine has led to a large amount of information overload, filling the public with different facts and contradictory information, labeled as “fake news,”Citation52 which has caused great controversy. Scholars are increasingly aware of the need to assess an individual’s knowledge, motivation, and ability to collect, understand, and use vaccine information. This has led to increased attention being paid to this topic.

The number of VL articles published is highest in 2022, and Table S6 lists the main research topics in this year. The research mainly focuses on the conceptual analysis of VL, the measurement of VL levels in different populations, and the revision and testing of VL measurement tools. In addition, some researchers have proposed digital VL and developed related measurement tools.

Regardless of publications, citations, or connections with other countries, organizations, and authors, the United States is in a prominent leading position. Seven of the top 10 organizations with the highest number of publications were from the United States. Countries such as England, China, Australia, and India have also made corresponding contributions. Table S7 lists the major studies in the top three countries. The United States conducted positive analyses of the importance of VL, the assessment of VL levels, the relationship between VL and vaccination, and the relationship between HL and vaccination. England has mainly carried out the assessment of VL levels, and the relationship between VL, HL, digital HL and vaccination. China has conducted research on the relationship between VL, HL, vaccination and vaccine hesitancy, as well as the development of the Chinese version of the COVID-19 VL measurement tool. It is clear that research on VL is closely related to HL, vaccine hesitancy and vaccination. The most prolific organizations in this field were Harvard University. Emory University was the most connected organization. These countries have made outstanding contributions to this field probably because of their in-depth research on vaccination hesitancy,Citation53 which has laid a solid foundation for VL research. Moreover, it may be due to the increasing hesitancy toward vaccines in these countries that has led to a shift toward research on VL to address the issue of vaccine hesitancy.Citation6–56 Additionally, as two middle-income countries with large populations, China and India ranked in the top 10 in terms of publications and citations, indicating that middle-income countries are making increasing contributions to research. In the future, collaboration between low- and middle-income countries and high-income countries should be strengthened to better promote research on VL.

Bonaccorsi G, Lorini C, and Lee HY were the top three most productive authors, with Bonaccorsi G being the most frequently cited and influential author in the field. The most prolific authors began publishing in 2017–2018, perhaps related to the effects of measles outbreaks and anti-vaccine campaigns mentioned above. The contributions of the lead authors are listed in Table S8. Bonaccorsi G, Biasio LR, and Lorini C started publishing in the field in 2018, but the contributions were outstanding. They studied the concept of VL, measurement tools, and the measurement of VL levels. It was pointed out that the current study did not pay enough attention to VL, and specific measurement tools to measure VL should be developed. Lee HY et al. mainly explored human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination status, HPV literacy, and its influencing factors.

The five most productive journals were primarily related to vaccines and public health. VACCINES had the highest number of published papers and h-index, and HUMAN VACCINES & IMMUNOTHERAPEUTICS was cited the most, indicating that they play an important role in VL research. From 2020 to 2023, the number of articles published by the top five journals surged. Among them, VACCINES has seen an even greater increase in cumulative publications. This was largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the development of COVID-19 vaccines.

Among the top 10 most-cited publications, 50% are articles and 50% are reviews. The most-cited document sought to update the 2004 systematic review. The results showed that low HL was associated with poorer health outcomes and poorer use of healthcare services.Citation57 The second assessed the relationship between literacy and health outcomes, with patients with low literacy having poorer health outcomes. Patients with low literacy are typically 1.5 to 3 times more likely to experience a given adverse outcome.Citation58 The third publication focused on assessing the effects of decision aids for people facing treatment or screening decisions. Compared with usual care, decision aids were found to improve people’s knowledge of options and reduce their decisional conflict, which is related to feeling uninformed and unclear about their personal values.Citation59 Most of the top 10 cited documents were closely related to health outcome, HL and vaccine hesitancy, and there was a lack of specific research on VL. As mentioned above, the concept of VL was first elaborated in 2011, and research from 1982 to 2011 laid the foundation for formally forming the concept of VL. However, in subsequent studies, VL was not well distinguished from HL. Several studies have focused on the relationship between vaccination, vaccine hesitancy, and HL.Citation14–62 Certainly, the term “health literacy” is more familiar than “vaccine literacy.”Citation6 However, capacities and knowledge of vaccines, vaccinations, and vaccination programs are remarkably specific, and even individuals with broad HL skills may lack specific competencies, including vaccination,Citation11 suggesting that VL is more specialized and not exactly equivalent to HL. However, individuals with appropriate levels of functional, interactive, and even critical literacy can be at risk of assessment errors, and a good level of education does not always correspond to an appropriate ability to interpret information critically.Citation9 This also suggests that future studies should be differentiated. Although the research results of HL can be referenced, research on VL should be focused on so that the research can be more in-depth and targeted.

The VOSviewer tool was used to analyze major research topics on VL. Four clusters were obtained through cluster analysis.

Cluster 1 focuses more on the relationship between people’s HL, vaccine hesitancy, vaccination and VL, and also related to the influence of the media environment and false and misinformation about vaccines on vaccination. The relationship between HL, vaccine hesitancy, vaccination and VL is listed in Table S9. Research found that the higher the HL level, the higher the percentage of “good” or “sufficient” VL; the lower the HL level, the higher the percentage of “limited” VL.Citation22 Scholars have measured the level of VL of adults and the diseased population,Citation20–23–Citation25 and the results show that most VL is at a medium level. The level of VL needs to be further improved. VL was associated with gender,Citation19 age,Citation24,Citation63 the level of education,Citation19,Citation24,Citation63 economic deprivation,Citation22 area of residence, and socioeconomic status (Table S10).Citation19 However, the results are not always consistent. Regarding age, some studies have found that VL decreases with age,Citation24 but others found that VL increases with age.Citation63 Therefore, the factors influencing VL need further investigation.

Previous studies have shown a negative correlation between VL and vaccine hesitancy.Citation16 VL and attitudes are important factors affecting vaccination intention.Citation64 However, some studies have also found no association between VL and willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19.Citation25,Citation65 The more complex relationship between VL, vaccination and vaccine hesitancy needs to be further explored. Reliance on television, social mediaCitation5,Citation66 and the InternetCitation67 for vaccine information is a common phenomenon, but many can be sources of fake news.Citation28 It can lead to increased vaccine hesitancy. A survey showed that medical staff were the most trusted sources of information on the COVID-19 vaccine.Citation68 Strengthening VL is an important tool to combat misinformation.Citation69 Public VL can be improved through education.Citation70

Cluster 2 pays more attention to the vaccination and health status of children. A scoping review showed that the public acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine for children and adolescents ranged from 4.9% (mothers in southeast Nigeria) to 91% (parents in Brazil).Citation71 The current study found no significant association between VL and parental willingness to vaccinate children against COVID-19.Citation27,Citation72 However, VL enhances one’s understanding; thus, it is involved in the decision-making process regarding vaccination.Citation28 There is a need to improve VL among parents and teach them which sources and how to obtain reliable knowledge from healthcare professionals.Citation72

Cluster 3 focuses more on COVID-19 vaccine and influenza vaccine. With the COVID-19 pandemic, how to increase COVID-19 vaccination rates has become a global concern.Citation13 Research involving COVID-19 vaccines has become an important area of VL research.Citation5 The influenza vaccine is one of the most effective ways to prevent influenza infection and reduce influenza hospitalizations and deaths.Citation73 However, influenza vaccine coverage remains low in young and middle-aged groups.Citation74 Influenza VL directly affects influenza vaccination,Citation75 and can also affect vaccination rates by influencing health beliefs.Citation76 A prior study found that vaccination confidence and literacy were positively correlated with vaccination intention.Citation77 Based on these findings, targeted interventions can be made to increase population vaccination rates.

Cluster 4 focuses more on the knowledge of female groups regarding specific diseases or vaccines. Due to literacy, education, and the digital divide, women are less likely than men to have access to relevant or credible vaccine information. Women have lower levels of trust in vaccines than men.Citation78 Knowledge and awareness of HPV, cancer, and HPV vaccines remain low among Nepali women,Citation79 and the focus on female groups is also aimed at trying to change this gender barrier. One study showed that higher HPV literacy was an important factor associated with HPV vaccination completion in female undergraduates.Citation80 Another study found a significantly higher risk of vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women with low interactive/critical skills. For mothers of young children, low functional skills and low interactive/critical skills had a significantly higher risk of vaccine hesitancy.Citation81

Previous studies have indicated that VL is associated with gender, and as children are a priority group for vaccination, there may also be differences in the effect of parents’ VL on childhood vaccination or vaccine hesitancy, but most of the current studies have examined the effect of VL on vaccine hesitancy and vaccination using children’s parents as a whole, with less in-depth exploration of this gender difference.Citation27–29,Citation82 Clusters 2 and 4 showed that it is possible to further explore whether and why there is a gender difference between mothers’ and fathers’ VL on childhood vaccination or vaccine hesitancy, in order to develop appropriate strategies to improve childhood vaccination.

Based on the above analysis, the major research topics of VL mainly focus on vaccination, HL, vaccine hesitancy, and the COVID-19 vaccine.

From the above analysis, although research on VL has made some progress, there are still some problems worthy of further research. The study groups were mainly adults, females, parents, and patients. More groups, such as adolescents, could be focused on. The concept of VL should be further developed. Although this has been explored by scholars, it still needs to be further perfected to reach a consensus on this concept.

Factors influencing VL, such as whether and how gender, age, etc., affect VL should be explored in more depth. The relationship between VL, vaccination and vaccine hesitancy also needs to be further explored. For example, the mediating role of factors such as vaccine confidence and health beliefs in vaccination and VL. Future research can further explore gender differences in VL between fathers and mothers in children’s vaccination or vaccine hesitancy.

The existing research results also indicate that the overall level of VL in the whole population needs to be further improved and that more tools or specific dimensions for measuring VL need to be developed, such as whether specific measuring tools are different owing to differences between different populations and different vaccines, to conduct dynamic monitoring of VL in the population and targeted interventions. It has important implications for health equity. The surveys were mainly cross-sectional. Due to the dynamic nature of VL, more longitudinal studies are needed in the future.

This study has some limitations. First, only English articles were included in this study; articles from other languages were not included, which may have omitted some non-English literature. Second, new papers published after the search date were excluded because the database remained open. Third, both the Bibliometix tool and the VOSviewer software have their own limitations, so it is best to combine data analysis with other software.

Conclusions

The current literature lacks bibliometric analysis in the field of VL. This study conducted bibliometric and visual analyses to visually display the annual publication trends, productive countries, organizations, authors, journals, cited publications, and keywords of VL research to provide a reference for future research. The results show that researchers have paid more attention to the study of VL, and all aspects reflect that the United States has made outstanding contributions to VL. Cooperation between countries may contribute to further research on VL. Vaccination, HL, vaccine hesitancy, and COVID-19 vaccine are major topics in VL research. Measles outbreaks, the COVID-19 pandemic, the anti-vaccination movement, and vaccine hesitancy are possible reasons for the increase in VL research. In the future, the concept of VL needs to continue to improve, and the complex relationship between VL, HL, vaccine hesitancy, and vaccination needs to be further explored. The gender differences observed are worthy of further investigation. VL measurement tools or specific dimensions applicable to different populations and vaccines should be developed and improved. Other groups, such as adolescents, could receive more attention. Due to the dynamic nature of VL, more longitudinal studies could be conducted.

Author contributions statement

Jingzhi Wang and Mingli Jiao contributed to conception and design of the study. Jingzhi Wang, Yazhou Wang and Yuanheng Li organized the database. Jingzhi Wang, Mingxue Ma, Yuzhuo Xie, Yuwei Zhang, and Jiaqi Guo performed the statistical analysis. Jingzhi Wang, Jiajun Shi, Chao Sun, Haoyu Chi, Hanye Tang, and Vsevolod Ermakov wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Mingli Jiao, Yazhou Wang and Yuanheng Li wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to this article and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Supplementary Material.docx

Download MS Word (556 KB)Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my supervisor for her guidance and help in the process of my thesis conception and writing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2024.2363019

Additional information

Funding

References

- Koppaka R. Ten great public health achievements-Worldwide, 2001-2010 (reprinted from MMWR vol 60, pg 814–818, 2011). Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 2011;306(5):484–12.

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081.

- MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- World Health Organization. Ten threats to global health in 2019. [accessed 2024 Jan 23]. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- Biasio LR, Zanobini P, Lorini C, Monaci P, Fanfani A, Gallinoro V, Cerini G, Albora G, Del Riccio M, Pecorelli S. COVID-19 vaccine literacy: a scoping review. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2023;19(1):27. doi:10.1080/21645515.2023.2176083.

- Badua AR, Caraquel KJ, Cruz M, Narvaez RA. Vaccine literacy: a concept analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2022;31(4):857–67. doi:10.1111/inm.12988.

- MacDonald N, Pickering L. Infect dis immunization C. Canada’s eight-step vaccine safety program: vaccine literacy. Paediatr Child Health. 2009;14(9):605–8. doi:10.1093/pch/14.9.605.

- Ratzan SC. Vaccine literacy: a new shot for advancing health. J Health Commun. 2011;16(3):227–9. doi:10.1080/10810730.2011.561726.

- Biasio LR. Vaccine literacy is undervalued. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2019;15(11):2552–3. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1609850.

- Michel JP, Goldberg GJ. Education, healthy ageing and vaccine literacy. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(5):698–701. doi:10.1007/s12603-021-1627-1.

- Chiara L, Marco D, Patrizio Z, Roberto BL, Paolo B, Duccio G, Ferro VA, Guazzini A, Maghrebi O, Lastrucci V. Vaccination as a social practice: towards a definition of personal, community, population, and organizational vaccine literacy. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):11. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-16437-6.

- Sirikalyanpaiboon M, Ousirimaneechai K, Phannajit J, Pitisuttithum P, Jantarabenjakul W, Chaiteerakij R, Paitoonpong L. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy, and determinants among physicians in a university-based teaching hospital in Thailand. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):12. doi:10.1186/s12879-021-06863-5.

- Zhang EM, Dai ZY, Wang SX, Wang XL, Zhang X, Fang Q. Vaccine literacy and vaccination: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2023;68:7. doi:10.3389/ijph.2023.1605606.

- Lorini C, Santomauro F, Donzellini M, Capecchi L, Bechini A, Boccalini S, Bonanni P, Bonaccorsi G. Health literacy and vaccination: a systematic review. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14(2):478–88. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1392423.

- Biasio LR, Giambi C, Fadda G, Lorini C, Bonaccorsi G, D’Ancona F. Validation of an Italian tool to assess vaccine literacy in adulthood vaccination: a pilot study. Ann Ig Med Prev Comunita. 2020;32:205–22.

- Yang LQ, Zhen SQ, Li L, Wang Q, Yang GP, Cui TT, Shi N, Xiu S, Zhu L, Xu X. Assessing vaccine literacy and exploring its association with vaccine hesitancy: a validation of the vaccine literacy scale in China. J Affect Disord. 2023;330:275–82. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.03.014.

- Maneesriwongul W, Butsing N, Visudtibhan PJ, Leelacharas S, Kittipimpanon K. Translation and psychometric testing of the Thai COVID-19 vaccine literacy scale. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res. 2022;26:175–86.

- Durmus A, Akbolat M, Amarat M. Turkish validity and reliability of COVID-19 vaccine literacy scale. Cukurova Med J. 2021;46(2):732–41. doi:10.17826/cumj.870432.

- Correa-Rodríguez M, Rueda-Medina B, Callejas-Rubio JL, Ríos-Fernández R, de la Hera-Fernández J, Ortego-Centeno N. COVID-19 vaccine literacy in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(16):13769–84. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-02713-y.

- Biasio LR, Bonaccorsi G, Lorini C, Mazzini D, Pecorelli S. Italian adults’ likelihood of getting COVID-19 vaccine: a second online survey. Vaccines. 2021;9(3):8. doi:10.3390/vaccines9030268.

- Biasio LR, Bonaccorsi G, Lorini C, Pecorelli S. Assessing COVID-19 vaccine literacy: a preliminary online survey. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(5):1304–12. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1829315.

- Cadeddu C, Regazzi L, Bonaccorsi G, Rosano A, Unim B, Griebler R, Link T, De Castro P, D’Elia R, Mastrilli V. The determinants of vaccine literacy in the Italian population: results from the health literacy survey 2019. Int J Environ Res and Public Health. 2022;19(8):13. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084429.

- Costantini H. COVID-19 vaccine literacy of family carers for their older parents in Japan. Healthcare. 2021;9(8):11. doi:10.3390/healthcare9081038.

- Gusar I, Konjevoda S, Babic G, Hnatesen D, Cebohin M, Orlandini R, Dželalija B. Pre-vaccination COVID-19 vaccine literacy in a Croatian adult population: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res and Public Health. 2021;18(13):10. doi:10.3390/ijerph18137073.

- Nath R, Imtiaz A, Nath SD, Hasan E. Role of vaccine hesitancy, eHealth literacy, and vaccine literacy in young adults’ COVID-19 vaccine uptake intention in a lower-middle-income country. Vaccines. 2021;9(12):13. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121405.

- Aharon AA, Nehama H, Rishpon S, Baron-Epel O. Parents with high levels of communicative and critical health literacy are less likely to vaccinate their children. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(4):768–75. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2016.11.016.

- Gendler Y, Ofri L. Investigating the influence of vaccine literacy, vaccine perception and vaccine hesitancy on Israeli parents’ acceptance of the covid-19 vaccine for their children: a cross-sectional study. Nato Adv Sci Inst Se. 2021;9(12):12. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121391.

- Maneesriwongul W, Butsing N, Deesamer S. Parental hesitancy on COVID-19 vaccination for children under five years in Thailand: role of attitudes and vaccine literacy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2023;17:615–28. doi:10.2147/PPA.S399414.

- Wang XM, Zhou XD, Leesa L, Mantwill S. The effect of vaccine literacy on parental trust and intention to vaccinate after a major vaccine scandal. J Health Commun. 2018;23(5):413–21. doi:10.1080/10810730.2018.1455771.

- Ogunsakin RE, Ebenezer O, Ginindza TG. A bibliometric analysis of the literature on norovirus disease from 1991–2021. Int J Environ Res And Public Health. 2022;19(5):27. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052508.

- Tao X, Hanif H, Ahmed HH, Ebrahim NA. Bibliometric analysis and visualization of academic procrastination. Front Psychol. 2021;12:18. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722332.

- Zhang D, Xu JP, Zhang YZ, Wang J, He SY, Zhou X. Study on sustainable urbanization literature based on web of science, Scopus, and China national knowledge infrastructure: A scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. J Clean Prod. 2020;264:11. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121537.

- Akintunde TY, Chen SJ, Musa TH, Amoo FO, Adedeji A, Ibrahim E, Tassang AE, Musa IH, Musa HH. Tracking the progress in COVID-19 and vaccine safety research – a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of publications indexed in Scopus database. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(11):3887–97. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1969851.

- Aria M, Cuccurullo C. Bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J Informetr. 2017;11(4):959–75. doi:10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007.

- Hao TY, Chen XL, Li GZ, Yan J. A bibliometric analysis of text mining in medical research. Soft Comput. 2018;22(23):7875–92. doi:10.1007/s00500-018-3511-4.

- van Eck NJ, Waltman L, van Eck NJ. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics. 2010;84(2):523–38. doi:10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3.

- Oyewola DO, Dada EG. Exploring machine learning: a scientometrics approach using bibliometrix and VOSviewer. SN Appl Sci. 2022;4(5):18. doi:10.1007/s42452-022-05027-7.

- Wang WG, Wang H, Yao T, Li YD, Yi LZ, Gao Y, Lian J, Feng Y, Wang S. The top 100 most cited articles on COVID-19 vaccine: a bibliometric analysis. Clin Exper Med. 2023;23(6):2287–99. doi:10.1007/s10238-023-01046-9.

- Guo YM, Huang ZL, Guo J, Guo XR, Li H, Liu MY, Ezzeddine S, Nkeli MJ. A bibliometric analysis and visualization of blockchain. Futur Gener Comp Syst. 2021;116:316–32. doi:10.1016/j.future.2020.10.023.

- Ejaz H, Zeeshan HM, Ahmad F, Bukhari SNA, Anwar N, Alanazi A, Sadiq A, Junaid K, Atif M, Abosalif KOA. Bibliometric analysis of publications on the omicron variant from 2020 to 2022 in the Scopus database using R and VOSviewer. Int J Environ Res and Public Health. 2022;19(19):25. doi:10.3390/ijerph191912407.

- Halbach OVU. How to judge a book by its cover? How useful are bibliometric indices for the evaluation of “scientific quality” or “scientific productivity”? Ann Anat-Anat Anz. 2011;193(3):191–6. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2011.03.011.

- Siani A. Measles outbreaks in Italy: a paradigm of the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable diseases in developed countries. Prev Med. 2019;121:99–104. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.02.011.

- Hester G, Nickel A, LeBlanc J, Carlson R, Spaulding AB, Kalaskar A, Stinchfield P. Measles hospitalizations at a United States children’s hospital 2011–2017. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38(6):547–52. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002221.

- Thompson S, Meyer JC, Burnett RJ, Campbell SM. Mitigating vaccine hesitancy and building trust to prevent future measles outbreaks in England. Vaccines. 2023;11(2):23. doi:10.3390/vaccines11020288.

- Béraud G, Abrams S, Beutels P, Dervaux B, Hens N. Resurgence risk for measles, mumps and rubella in France in 2018 and 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2018;23(25):2–12. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.25.1700796.

- Ashkenazi S, Livni G, Klein A, Kremer N, Havlin A, Berkowitz O. The relationship between parental source of information and knowledge about measles/measles vaccine and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2020;38(46):7292–8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.044.

- He Q, Wang H, Ma Y, Wang ZW, Zhang ZB, Li TG, Yang Z. Changes in parents’ decisions pertaining to vaccination of their children after the Changchun Changsheng vaccine scandal in Guangzhou, China. Vaccine. 2020;38(43):6751–6. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.039.

- Kalichman SC, Eaton LA. The emergence and persistence of the anti-vaccination movement. Health Psychol. 2023;42(8):516–20. doi:10.1037/hea0001273.

- Ahmad T, Murad MA, Baig M, Hui J. Research trends in COVID-19 vaccine: a bibliometric analysis. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(8):2367–72. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1886806.

- Gan PL, Pan X, Huang S, Xia HF, Zhou X, Tang XW. Current status of coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine research based on bibliometric analysis. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(6):12. doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2119766.

- Masiello MM, Harton P, Parker RM. Building vaccine literacy in a pandemic: how one team of public health students is responding. J Health Commun. 2020;25(10):753–6. doi:10.1080/10810730.2020.1868629.

- Smith R, Chen K, Winner D, Friedhoff S, Wardle C. A systematic review of COVID-19 misinformation interventions: lessons learned. Health Aff (Millwood). 2023;42(12):1738–46. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00717.

- Chen CJ, Yang QP, Tian HT, Wu JY, Chen LZ, Ji ZQ, Zheng D, Chen Y, Li Z, Lu H. Bibliometric and visual analysis of vaccination hesitancy research from 2013 to 2022. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2023;19(2):15. doi:10.1080/21645515.2023.2226584.

- Majid U, Ahmad M, Zain S, Akande A, Ikhlaq F. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance: a comprehensive scoping review of global literature. Health Promot Int. 2022;37(3):12. doi:10.1093/heapro/daac078.

- Shah AS, Coiado OC. COVID-19 vaccine and booster hesitation around the world: a literature review. Front Med. 2023;9:12. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.1054557.

- Yang RH, Penders B, Horstman K. Addressing vaccine hesitancy in China: a scoping review of Chinese scholarship. Vaccines. 2020;8(1):17. doi:10.3390/vaccines8010002.

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97±. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005.

- Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19(12):1228–39. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x.

- Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, Holmes‐Rovner M., Llewellyn‐Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, Trevena L. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;335(1). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001431.Pub4.

- Kocaay F, Yigman F, Unal N. COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy: could health literacy be the solution? Bezmialem Sci. 2022;10(6):763–9. doi:10.14235/bas.galenos.2022.83584.

- Rowlands G. Health literacy ways to maximise the impact and effectiveness of vaccination information. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2014;10(7):2130–5. doi:10.4161/hv.29603.

- Turhan Z, Dilcen HY, Dolu İ. The mediating role of health literacy on the relationship between health care system distrust and vaccine hesitancy during COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(11):8147–56. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02105-8.

- Li YH, Guo Y, Wu XS, Hu QY, Hu DH. The development and preliminary application of the Chinese version of the COVID-19 vaccine literacy scale. Int J Environ Res And Public Health. 2022;19(20):17. doi:10.3390/ijerph192013601.

- Kittipimpanon K, Maneesriwongul W, Butsing N, Visudtibhan PJ, Leelacharas S. COVID-19 vaccine literacy, attitudes, and vaccination intention against COVID-19 among Thai older adults. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:2365–74. doi:10.2147/PPA.S376311.

- Carter J, Rutherford S, Borkoles E. COVID-19 vaccine uptake among younger women in Rural Australia. Nato Adv Sci Inst Se. 2022;10(1):13. doi:10.3390/vaccines10010026.

- Suran M. Why parents still hesitate to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 2022;327(1):23–5. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.21625.

- Babicki M, Mastalerz-Migas A. Attitudes toward vaccination against COVID-19 in Poland. A longitudinal study performed before and two months after the commencement of the population vaccination programme in Poland. Vaccines. 2021;9(5):12. doi:10.3390/vaccines9050503.

- Szilagyi PG, Shah MD, Delgado JR, Thomas K, Vizueta N, Cui Y, Vangala S, Shetgiri R, Kapteyn A. Parents’ intentions and perceptions about COVID-19 vaccination for their children: results from a National survey. Pediatrics. 2021;148(4):11. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-052335.

- Popa AD, Enache AI, Popa IV, Antoniu SA, Dragomir RA, Burlacu A. Determinants of the hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination in Eastern European Countries and the relationship with health and vaccine literacy: a literature review. Vaccines. 2022;10(5):14. doi:10.3390/vaccines10050672.

- Lu YS, Wang QF, Zhu S, Xu S, Kadirhaz M, Zhang YS, Zhao N, Fang Y, Chang J. Lessons learned from COVID-19 vaccination implementation: How psychological antecedents of vaccinations mediate the relationship between vaccine literacy and vaccine hesitancy. Soc Sci Med. 2023;336:8. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116270.

- Liu Y, Ma Q, Liu H, Guo Z. Public attitudes and influencing factors toward COVID-19 vaccination for adolescents/children: a scoping review. Public Health. 2022;205:169–81. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2022.02.002.

- Bektas I, Bektas M. The effects of parents’ vaccine hesitancy and COVID-19 vaccine literacy on attitudes toward vaccinating their children during the pandemic. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2023;71:e70–e74. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2023.04.016.

- Grohskopf LA, Blanton LH, Ferdinands JM, Chung JR, Broder KR, Talbot HK. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices - United States, 2023–24 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2023;72(2):1–25.

- Shon EJ, Lee L. Effects of vaccine literacy, health beliefs, and flu vaccination on perceived physical health status among under/graduate students. Vaccines. 2023;11(4):15. doi:10.3390/vaccines11040765.

- Bennett IM, Chen J, Soroui JS, White S. The contribution of health literacy to disparities in self-rated health status and preventive health behaviors in older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):204–11. doi:10.1370/afm.940.

- Guclu OA, Demirci H, Ocakoglu G, Guclu Y, Uzaslan E, Karadag M. Relationship of pneumococcal and influenza vaccination frequency with health literacy in the rural population in Turkey. Vaccine. 2019;37(44):6617–23. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.049.

- Collini F, Bonaccorsi G, Del Riccio M, Bruschi M, Forni S, Galletti G, Gemmi F, Ierardi F, Lorini C. Does vaccine confidence mediate the relationship between vaccine literacy and influenza vaccination? exploring determinants of vaccination among staff members of nursing homes in Tuscany, Italy, during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines. 2023;11(8):13. doi:10.3390/vaccines11081375.

- Nassiri-Ansari T, Atuhebwe P, Ayisi AS, Goulding S, Johri M, Allotey P, Schwalbe N. Shifting gender barriers in immunisation in the COVID-19 pandemic response and beyond. Lancet. 2022;400(10345):24–. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01189-8.

- Johnson DC, Bhatta MP, Gurung S, Aryal S, Lhaki P, Shrestha S. Knowledge and awareness of human papillomavirus (HPV), cervical cancer and HPV vaccine among women in two distinct Nepali communities. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(19):8287–93. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.19.8287.

- Lee HY, Kwon M, Vang S, DeWolfe J, Kim NK, Lee DK, Yeung M. Disparities in human papillomavirus vaccine literacy and vaccine completion among Asian American Pacific Islander undergraduates: implications for cancer health equity. J Am Coll Health. 2015;63(5):316–23. doi:10.1080/07448481.2015.1031237.

- Takahashi Y, Ishitsuka K, Sampei M, Okawa S, Hosokawa Y, Ishiguro A, Tabuchi T, Morisaki N. COVID-19 vaccine literacy and vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women and mothers of young children in Japan. Vaccine. 2022;40(47):6849–56. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.09.094.

- Maneesriwongul W, Deesamer S, Butsing N. Parental vaccine literacy: attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccines and intention to vaccinate their children aged 5–11 years against COVID-19 in Thailand. Vaccines. 2023;11(12):15. doi:10.3390/vaccines11121804.