ABSTRACT

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the main cause of low respiratory tract infections in infants under one year of age. In the 2023/2024 season, the monoclonal antibody nirsevimab was available to protect children from RSV, and Spain has become one of the first countries worldwide to implement this strategy. It is essential to evaluate the results of this first campaign and different characteristics of the immunized population in order to plan next campaigns, especially for countries that are going to include this immunization. Our coverage was high (91.5% for those born during the season and 88.3% globally). For those born during the season, only 4.9% preferred not to immunize at the maternity hospital, which meant an average delay of 27.45 days. We observed a lower coverage in the population of immigrant origin. There was a rapid pace of immunization, since for those born before the beginning of the campaign the mean to be immunized was 15.63 days, without differences between healthy and at-risk children. This allows immunization before the RSV season (90% of the catch-up children had been immunized on November 3). The average age at which all the immunized children have received nirsevimab was lower in healthy children compared to those with risk conditions (49.65 versus 232.85 days). For those born during the campaign, the average age was also lower in healthy children (3.14 versus 14.58 days). In conclusion, we consider that the implementation of the immunization strategy with nirsevimab in the Region of Murcia, Spain, has been a success.

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the main cause of low respiratory tract infections (LRTI) in the infant population under one year of age.Citation1 RSV is a universal infection in childhood. Worldwide, it is the second cause of death in minors of one year.Citation2 In high-income countries, children under 3 months of age account for 57.9% of admissions in children under one year of ageCitation3 and the hospital admission rate is higher in the first 6 months of life.Citation4 In Spain, in terms of burden on the health system, 937,135 and 701,579 consultations have been estimated RSV infection in primary care nationwide in the 2021–2022 seasons and in 2022–2023 (until week 10/2023), respectively, assuming the group of children under 5 years of age over 230,000 consultations per season. In relation to serious cases 32,787 and 22,913 are estimated RSV hospitalizations nationwide, in the same period, of which children under 5 years of age would account for 11,522 and 17,102 hospitalizations, respectively.Citation5 According to unpublished data provided by the different pediatric services, between 2015–2016 and 2019–2020 seasons (the last season prior to the COVID-19 pandemic), at the Virgen de la Arrixaca University Clinical Hospital (the main pediatric hospital in the Region of Murcia, which directly serves 62% of the pediatric population and is a reference for the entire region), an average of 360 children under 1 year of age were admitted for RSV-associated LRTI per season. In addition, there are also unpublished data available for the whole Region for the 2022–2023 season, in which admissions for bronchiolitis amounted to 633, 433 of them were RSV-associated; of these, 339 corresponded to children under one year of age, 50 of them in Neonatology and 38 in the Intensive Care Unit.

In October 2022, nirsevimab, an extended half-life humanized IgG1k class monoclonal antibody (mAb), directed against the antigenic site Ø of the RSV F protein in its prefusion conformation, was authorized by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). This mAb, with a single dose, confers protection throughout the season for, at least, 5 months.Citation6 Different studies have evaluated its efficacy, with the most recently published showing an efficacy of 83.21% (95% CI 67.77–92.04%) in preventing hospitalization due to RSV lower respiratory tract infection, while against very severe forms it was 75.71% (95% CI 32.75–92.91%).Citation7 Early real-world data are beginning to be published, providing evidence that nirsevimab protects infants against hospitalization for RSV-associated LRTI has an important impact.Citation8,Citation9 This drug has also shown an adequate safety profile in clinical trials.Citation10 Previously, the only RSV pharmacological preventive strategy available in Spain and which, therefore, was being applied in the Region of Murcia was the mAb palivizumab, for use restricted to infants with certain risk conditions (preterm infants ≤32 weeks gestational age ≤6 months of age and children ≤24 months with chronic lung disease/bronchopulmonary dysplasia, significant congenital heart disease, Down syndrome, pulmonary/neuromuscular disorders, immunocompromised, and cystic fibrosis) and administered in a hospitable way monthly throughout the season.Citation11,Citation12

The authorization of nirsevimab, as well as the burden of disease caused by RSV, motivated the recommendation, approved by the Spanish National Immunization Technical Advisory Group (NITAG) on May 2023, for its administration in children under 6 months of age born from April 1, 2023, to March 31, 2024, as well as to preterm babies up to 34 weeks of gestation under one year of age and children with other risk conditions (congenital heart diseases with significant hemodynamic involvement, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, severe immunosuppression, inborn errors of metabolism, neuromuscular disorders, severe lung diseases, genetic syndromes with relevant respiratory problems, Down syndrome, cystic fibrosis, and people in palliative care) under 2 years of age.Citation5 From there, different autonomous communities began the procurement process and preparation of the campaign on different dates depending on each one. In this way, Spain has become one of the first countries worldwide to implement this strategy in the 2023-2024 campaign.

Spain is a country with 17 communities and 2 autonomous cities in which competencies in health and vaccination programs are transferred to the different autonomous cities and communities, being the Region of Murcia one of them. Therefore, the date of start of the campaign and the activities carried out to implement it were different in each of them. The Region of Murcia was one of the first autonomous communities to begin the campaign on September 25, 2023. The Region of Murcia is an autonomous community located in the southeast of Spain, with a population of 1,552,457 inhabitants according to the 2023 official population censusCitation13 and 13,404 births in 2022, 4.07% of the total national cohort.Citation14

Several studies have been published about the real-world data effectiveness of nirsevimab,Citation8,Citation15–17 but, to our knowledge, there are no robust evaluations of this first RSV-immunization campaign conducted in particular countries/regions, which could serve as a guide for subsequent campaigns and other regions. This is why the primary objective of the present paper was to describe the process of implementing the first immunization campaign against RSV in the 2023-2024 season in our autonomous community, the first time that a mAb was used universally. The secondary objective was to evaluate the demographic characteristics of the immunized population of those born between April 1, 2023, and March 31, 2024, and the coverage obtained, as a result of all actions carried out during the campaign.

Materials and methods

Evaluation carried out

A retrospective cross-sectional evaluation was carried out on April 8, 2024, of those children born from April 1, 2023, to March 31, 2024, immunized with nirsevimab. Demographic characteristics available in the population database of them and health card holder (usually the mother) were collected. Immunization coverages were calculated differentiating between two groups: those born out of season (from April 1 to September 24, 2023) and before the campaign began and those born during the RSV immunization campaign (from September 25, 2023, to March 31, 2024). The first ones were immunized at their primary health care centers and regular immunization posts as a catch-up campaign, while the second ones were immunized before discharge from the maternity hospital (preferably in the first 48 h of life) or, in cases of refusal, immunization was offered at their healthcare centers and regular immunization posts on every visit.

Campaign organization and logistics

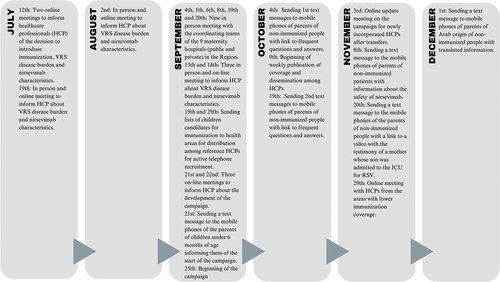

Preparatory and informative meetings were held, both online and in person, to inform healthcare professionals (HCP) about RSV burden of disease and product characteristics before the beginning of the campaign. In addition, nine face-to-face meetings were held by a team from the Vaccination Program of the regional Ministry of Health with a coordinator team in each maternity hospital (usually made up of medical and nursing management personnel, supervisors of maternity, pediatric, and neonatology wards, as well as chiefs of pediatric services, preventive specialists, and pharmacists). From October 9, weekly immunization coverages were published in https://www.murciasalud.es/web/vacunacion/-/virusrespiratoriosincitial. All these activities that have been carried out until December 31, 2023, in the Region of Murcia are described in .

Figure 1. Chronology of all the development and activities carried out in the 2023-2024 RSV immunization campaign until December 31, 2023.

For training and information to families, information brochures were prepared with frequently asked questions about the new campaign, which were translated into Arabic (largest immigrant population with language difficulties). These brochures were available in health centers, regular immunization posts, and maternity hospitals, as well as campaign information posters. These frequently asked questions were also developed on a specific website. Likewise, specific material was developed for midwives to support maternal education. Subsequently, the HCPs were asked to make videos recommending immunization and to post them on different social media. All of this is available on the aforementioned website.

Other ways of trying to reach the target population of the campaign were sending text messages to mobile phones (SMS), with a link to the frequently asked questions, translated for children of parents of Arab origin, as well as with messages about local product safety data after the beginning of the campaign (). Lists were also sent to each immunization post so that the HCP could actively recruit those non-immunized by telephone calls and be able to record refusals.

Evaluation variables and data source

The evaluation variables were as follows: date of birth (age), gender, birth country of the health card holder (usually the mother), date of nirsevimab administration, immunization post, product administered, reason of immunization and maternity where the baby was born for those born in RSV season. All data were obtained from the regional vaccination registry database (VACUSAN) and the population database (PERSAN). Both databases depend on the Prevention and Health Protection Service of the Regional Ministry of Health and are central databases, which include data on both people with public and private health care at the regional level. However, despite the fact that a national registry has been created in which nirsevimab doses are available, in addition to COVID-19 and Mpox vaccines (REGVACU); given that children do not have a unique identifier at birth, data on children born in other autonomous communities where they received the mAb in their first months of life may not be always available. This could have even led to underestimate coverages.

VACUSAN has different validations to avoid duplication of records by mistake. However, prior to the analysis, the quality of the data was evaluated and possible errors were filtered, mainly finding that the reason for immunization was not available, which was solved by consulting the medical history of each of the children, so that the analysis for this reason could be carried out correctly.

Statistical methods

The data were analyzed with the SPSS 25 statistical package for Windows.

Socio-demographic data of the children and their health card holder were expressed in the form of frequencies and percentages. Missing data were excluded upon calculating percentages. For quantitative variables, mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated. A comparative analysis of the two study groups (immunized and non-immunized) was carried out using the corresponding Chi-square tests for comparison of proportions. We performed data analysis both overall and stratified by moment of birth in relation to the campaign. Whereas the Student’s test was performed to compare quantitative variables between two groups. In the statistical analysis, a significance level of 5% (p-value of 0.05) was considered in all research hypothesis contrasts.

Ethics

We conducted the evaluation in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and national data protection legal and ethical requirements. The Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of Virgen de la Arrixaca University Clinical Hospital, which is the reference center of the Region of Murcia, evaluated the protocol, but approval was waived due to the characteristics of the evaluation as part of a public health program.

Results

The evaluation included 11,560 immunized children born between April 1, 2023, and March 31, 2024 (88.3%) of a total of 13,086 children. We observed a significantly higher immunization coverage in those born during the campaign (91.5%) than in those born before the beginning of it (85.1%) (p < .001). Taking into consideration the entire population to be immunized, the coverage was also greater in children whose health card holder was born in Spain (91.3%) compared to those of migrants (85.6%) (p < .001), with differences also according to the country of birth of the holder classified by WHO Health Regions, as indicated in , together with all the other sociodemographic data for both immunized born during the campaign and before it. We did not observe statistically significant differences in coverage based on the sex of the babies.

Table 1. Sociodemographic data of immunized and non-immunized children, born before the beginning of the campaign or during it.

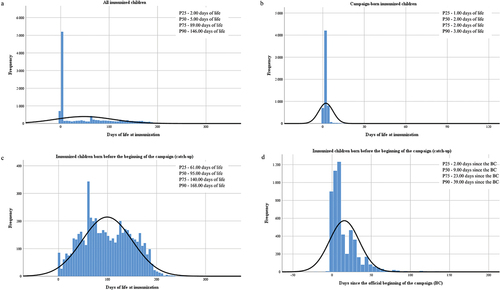

One piece of data evaluated was the days of life at which children born between April 1, 2023, and March 31, 2024, have received nirsevimab, both globally and separately for those born since the beginning of the campaign and those born before it. ) shows these data. Taking into account all those immunized, they received nirsevimab between the first hours of life and the day 299, with a mean of 48.01 days (standard deviation, SD, 59.40 days) and a median of 5.00 days. These children could be divided into two groups:

Figure 2. Frequency distribution of immunization. (a) Days of life at immunization of all the children born from April 1, 2023 to March 31, 2024. (b) Days of life at immunization of children born during the campaign, from September 25, 2023 to March 31, 2024. (c) Days of life at immunization of children born before the beginning of the campaign, from April 1 to September 24, 2023. (d) Days since the official beginning of the campaign that it took children born before the beginning of the campaign, from April 1 to September 24, 2023, to be immunized.

Born during the campaign: They were immunized in a range between 0 and 143 days of life, the mean was 3.48 days (SD 9.22) and the median 2.00 days (). In this group, taking into account only those immunized at the hospital before discharge, the maximum days of life at immunization were also 112 days (a preterm infant) and the mean to 2.25 (SD 5.18). However, there were 306 families that refused the immunization with nirsevimab in the maternity hospital and children received afterward the antibody at their healthcare center or usual vaccination post; in this group, the mean days of life at immunization were 27.45 (SD 24.86).

Born before the beginning of the campaign: They were immunized in a range between 1 and 299 days of life, the mean was 99.16 days (SD 50.89) and the median 95.00 days ). Taking into account the number of days it took to be immunized since the official start of the campaign, the range went from −5 to 177 days with a mean of 15.63 days (SD 19.02) and a median of 9.00 days . Sons of migrant mothers were immunized significantly later (mean 19.83 days, SD 22.24) than those of Spanish mothers (mean 13.33, SD 16.10) (p < .001).

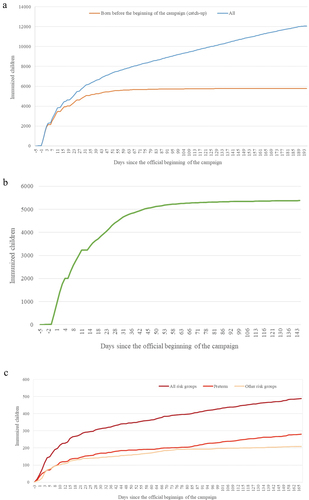

shows the rate of administration of nirsevimab doses in the analyzed period. compares the immunization rate of all children to those corresponding to the catch-up . shows the evolution of the cumulative immunization rate of children belonging to both risk condition groups. We made the catch-up in order to immunize the majority of those born before the beginning of the RSV season and the virus’ circulation. Reviewing only those doses, 25% of them were administered in the first 2 days of the official date of the beginning (there were doses registered from 5 days before it), 50% in the first 9 days, 75% in the day 23, and 90% in the day 39 (November 3).

Figure 3. Cumulative immunization rate with nirsevimab. (a) Comparison between the immunization rate of all children (blue) compared to those born before the start of the season (orange), corresponding to the catch-up. (b) Evolution of the cumulative immunization rate of healthy children born before the start of the campaign. (c) Evolution of the cumulative immunization rate of children with risk conditions born before the start of the campaign, both globally (maroon) and comparatively between the group of premature babies less than 12 months of age (light red) and the rest of the risk conditions under 24 months of age (peach).

We compared how long it took healthy children to be immunized with respect to those who belong to risk groups since the beginning of the campaign, taking into account only thosebelonging to the catch-up (born before September 25, 2023). There were no significant differences (p = .052) between children from risk groups, who were immunized on average on day 16.14 (SD 21.50), and healthy children, who were immunized on average on day 15.61 (SD 18.99).

Comparing the average age at which all the immunized children have received nirsevimab, this was significantly higher (p < .001) in those with risk conditions (mean 232.85 days, SD 271.80) versus healthy children (49.65 days, SD 64.72). Separating only those born before the beginning of the campaign, the mean age was also significantly higher (p < .001) in children with risk conditions (347.89 days, SD 272.48), versus healthy children (101.74 days, SD 60.54). However, taking into account only those born during the campaign, the average age was significantly lower (p < .001) in healthy children (3.14 days, SD 8.42, versus 14.58 days, SD 20.69).

In those born from April 1, 2023, until the beginning of the campaign, 4,238 doses administered were the 100 mg presentation (77.5%) and only 1,228 the 50 mg presentation (22.5%). Taking into account also those from other groups with risk conditions defined in the strategy, 4,552 100 mg doses were administered (78.6%) and 1,237 of the 50 mg ones (21.4%). Only 54 100 mg doses were administered in children born before April 1, 2023, without risk conditions and 2 from the 50 mg preparation (which means a use not adjusted to the protocol of 0.4% from 12,066 doses administered). On the other hand, in those born during the campaign, just 60 of the doses administered (0.1%) were 100 mg, with the rest of them being the 50 mg presentation (6,217, 99.9%).

In the Region of Murcia, nirsevimab was available for the immunization of healthy new-borns and infants and those with risk conditions in 85 health centers, 72 practices, and 6 public maternity hospitals, as well as 10 private vaccination posts and 2 private maternity hospitals.

Discussion

Spain has been one of the first countries to implement nirsevimab as a strategy to prevent RSV disease. This strategy has been effective, as we have previously shown a reduction of RSV-associated LRTI hospitalizations of 86.9% (CI 95% 77.1% to 92.9%) in infants under 9 months of age in our region and globally of 80.0% (CI 95% 76.8% to 90.0%) in the three autonomous communities studied in the first worldwide study of effectiveness against hospital admission for RSV-associated LRTI.Citation8 Later studies have shown similar effectiveness results both in our countryCitation15,Citation16 and in the United States78, but none of them have addressed all the implementation process. It is because of that, to our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of this type that describes this topic in detail, which can be very useful to other health authorities to plan next immunization campaigns.

In our region, the implementation strategy has been two site strategy (maternity hospitals and primary care centers or immunization posts) based on the objective of increasing accessibility to children born before the campaign, immunizing them at their nearest primary care center or immunization post, as well as early immunization prior to discharge from the maternity hospital in children born during the campaign and the RSV season. This strategy was followed in most autonomous communities, although there were a few, such as Madrid, that chose to immunize all children in hospitals. Similar strategies have been carried out in other countries, such as Luxembourg,Citation8 France (where children have been immunized at maternities and pharmacies instead of primary care centers),Citation18 and the United States.Citation19 Our coverage data were higher than those observed in Luxembourg (84 vs. 91.5% in the Region of Murcia), and the coverage of those born out of the season could not be compared as Luxembourg does not have records.Citation9 Nirsevimab coverage in the US has been 40.5% until January 24,Citation20 to which the vaccination coverage in pregnant women (16.2%)Citation21 should be added, so the global percentage of protected children is under 57%, which contrasts with that obtained in our Region of 88.3% in the evaluated period. We have not found coverage data in France, so we could not compare them to our data. Of the analyzed countries, only the United States recommended a combined strategy using nirsevimab and the maternal RSV vaccine,Citation22 something that could not be proposed in our country because the RSV vaccine was not available at the time of planning the strategy.

In a study on RSV and bronchiolitis knowledge carried out in 2020 in several countries including Spain, it was observed that parents of children under 2 years of age in our country had basic or good knowledge in 28% regarding RSV, while this figure increased to 79% if asked about bronchiolitis.Citation23 In a study carried out in Italy during 2023 among Italian pediatricians, 35.7% of them answered that did not exist passive immunization to prevent RSV for infants and new-borns aged <2 years.Citation24 We do not have previous data on the knowledge of our pediatricians, but they may be similar to those described in Italy; to this, we should add that pediatricians will be among the health care professionals best trained in this regard. This indicates that prior to the campaign it is necessary to train professionals and parents, prior to the birth of their children, about what is RSV and bronchiolitis. Definitely, the meetings and training offered in this regard may have contributed positively to the high immunization coverage reached. Another practice that may have contributed is the coverage evaluation and its publication weekly, a technique that is described as appropriate to increase vaccination coverage,Citation25 as well as active recruitment through text messages and phone calls from the health centers themselves.

We believe that the coverage achieved has been quite good, especially if we compare it with neighboring countries that have implemented RSV immunization in infants. In our region, we had never vaccinated universally in maternity hospitals, so this posed an additional challenge. In addition to an intense publicity and social media campaign by regional public health authorities that can explain the high coverage obtained, we believe that the role of pediatricians and pediatric nurses (who are highly aware of the burden of disease of RSV) has been fundamental in the information and active recruitment of the families of infants who are candidates to be immunized, which has had a high impact.

The coverage obtained for infants born during the campaign has been very high (91.5%); however, of the total number of immunized people, 306 families (4.9%) preferred not to immunize at the maternity hospital, doing so later at the health center, which meant a delay on average of 27.45 days, because they needed to consult with their referring pediatrician. It is necessary to reinforce the message of leaving the maternity ward immunized, since delaying immunization during the RSV season poses an unnecessary danger. We believe that this is something that can be improved in future seasons with more information and when the strategy is more consolidated in common practice. Another fundamental logistical point of the strategy is the need for interconnected information systems, which is the only thing that will ensure the correct handling of immunization.

The difference in coverage between the population of migrant origin and the Spanish one is something that has already been described in neighboring countries, such as GermanyCitation26 or ItalyCitation27 for other vaccinations, something that is lower in our environment in the first year of life (unpublished data), and that was also confirmed in our Region at the beginning of HPV vaccination.Citation28 The lower nirsevimab coverage was basically due to the populations from the Eastern Mediterranean and Eastern European Regions, data that were also verified in the initial vaccination against HPV. It is necessary to carry out specific actions with these populations, in addition to the translation of the texts already carried out, to reduce the differences in coverage with the Spanish population observed due to language barriers. Moreover, despite the statistically significant differences, both for those born during the campaign and before it, the proportion of non-immunized was lower in the migrant population born during the campaign. This may be due to the fact that immunization was carried out while the baby and his/her mother were admitted prior to hospital discharge, while immunized children born before the campaign did so in health care centers, which are only mostly open in the morning and may interfere with parents’ work activity. Parents of younger infants should be on paternal leave, but we know that in the migrant origin population there is a higher proportion of people working without a contract, and they will not be enjoying these benefits, which may be reflecting a greater accessibility problem in children of migrant origin. In addition, we cannot rule out that part of the migrant population is displaced in their countries of origin.

We consider an enormous success that those children born before the beginning of the campaign and out of the season managed to be immunized with an average of 15.32 days (13.33 children of national origin vs. 19.83 children of migrant origin) since the official beginning of the campaign and a median of 9.00 days, which demonstrates the great capacity of our health system to immunize quickly infants under 6 months of age, also coinciding with school flu vaccination, and reflects the awareness of pediatricians, nurses, and parents on this issue, in addition to the usefulness of active recruitment strategies used (SMS, phone calls, social networks, mass media, etc.). The start date of the campaign undoubtedly allows immunization before the circulation of RSV: 90% of these children born out of season had been immunized before November 3, which reinforces the capacity of the system. In any case, it is an issue that must be taken into account in planning to avoid any possible difficulty in the implementation of immunization.

Children at risk born before April 1, 2023, were immunized in hospitals following the usual circuit previously used for the administration of the mAb palivizumab, with an average number of days since the beginning of the campaign until their immunization of 14.92 days, similar to that described for healthy children born after April 1. This shows that the hospital circuit worked properly for children with at-risk pathologies and the fact that there was no difference between the immunization times of healthy and at-risk children demonstrates the great acceptance that the strategy has had in the general population in Spain.

The high demand is positive, but it can saturate the health system, something that must be taken into account, and especially the high quantity of doses needed at the beginning of the immunization campaign since, as we have seen, 83.6% of the 100 mg dosage will be administered during the first month of the campaign. It is essential to have good stock planning to avoid shortage problems, such as those that occurred in FranceCitation29 and the United States.Citation30

The average age at which all the immunized children have received nirsevimab was lower in healthy children compared to those with risk conditions (mean 49.65 days versus 232.85 days). Separating only those born before the beginning of the campaign, the mean age was also higher in children with risk conditions (347.89 days versus 101.74 days), which is logical since premature babies under 35 weeks of gestational age under 12 months and other risk groups under 24 months of age were included as a population susceptible to immunization. Taking into account only those born during the campaign, the average age was also lower in healthy children (3.14 days versus 14.58 days), given that children with risk conditions are admitted to Neonatology and Intensive Care Unit sections more frequently at birth and only receive nirsevimab when their underlying pathology is stable.

A difficulty in planning the campaign was estimating how many doses of each of the dosages were necessary. In our experience (variable depending on the population studied), children born out of season and at risk required a dosage of 100 mg in the 78.6% and 50 mg in the 21.4%. On the other hand, as is obvious, 99.0% of the children born during the campaign weighed less than 5 kg and received the 50 mg dose. We believe it is important to highlight the fact that there was little use outside the recommendations (0.4% of the total doses). This is important because, given the shortage of doses, some health authorities may consider restricting the use to hospitals to achieve a stricter use. However, what we have seen is that correct use was made according to the guidelines of the health authorities and, therefore, we believe that it is not worth reducing the access that the use of fewer centers would entail.

The cost of nirsevimab doses was similar to that of a “premium” vaccination schedule, such as the 4CMenB vaccine or the Herpes Zoster vaccine, which may seem high. However, taking into account that the average cost in the Region of palivizumab immunization program in previous campaigns only in children with high-risk conditions amounted over 850,000 euros, the differential investment with respect to previous campaigns could make a total cost similar to the rotavirus vaccination schedule or even less than the full pneumococcal vaccine vaccination schedule. In addition, we must bear in mind that previous studies have estimated an effectiveness of 86.9%,Citation7 based on data from the 2022-2023 season, it would mean a reduction in hospitalization of approximately 376 cases, which would also have a significant impact on hospital expenditure.

The absence of a national immunization registry system means that one of the limitations of the study may be the under-registration of doses in children born or who have been in the first months of the campaign in other autonomous communities. Another unavailable data that could be a limitation of the study is the nationality or country of origin of the father (since the vast majority of health card holders are mothers); however, in our region, most couples are concordant in their origin. Other factors that we have not evaluated, which could influence coverage, are level of vaccine hesitancy or socioeconomic level, but these are issues that are beyond the scope of this article, as well as real-world safety data and that are currently being evaluated by a survey, as well as families’ satisfaction and acceptance, comparing the opinions of those who have immunized to those who decided not to do so. These data collection is being finalized and would also give us a very valuable information. In immunization or vaccination campaigns as novel as this one, in addition to having data on the effectiveness or impact of the actions carried out, more evaluations of the implementation process are useful for other countries that follow in the same footsteps.

The data obtained from this evaluation are of great value for planning successive campaigns, and we also understand that for other health authorities to schedule the beginning of their own campaigns. As lessons learned, we must take into account the need of increasing accessibility for those born before the campaign and the importance of increasing, since the beginning of the campaign, both the information of the population globally, as well as the importance of early immunization in those born in season.

In conclusion, we consider that the implementation of the first RSV immunization campaign with the mAb nirsevimab in the Region of Murcia, Spain, in the 2023-2024 season, has been a success with a global coverage of 88.3%, higher for those born during the campaign (91.5%) than in those born before the beginning of it (85.1%). To achieve this success, it has been necessary information, training, and significant logistical capacity by Public Health, but also a collaborative effort of different pediatric healthcare professionals.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all involved healthcare professionals that contributed to this first RSV immunization campaign for their implication and that, with their work, they have prevented cases of serious illness in infants in our region.

Disclosure statement

J.J.P.M. declare having received funding from Sanofi for training and dissemination activities. M.Z.M. declare no disclosure of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Calvo C, Pozo F, García-García ML, Sanchez M, Lopez‐Valero M, Pérez‐Breña P, Casas I. Detection of new respiratory viruses in hospitalized infants with bronchiolitis: a three-year prospective study. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99(6):883–9. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01714.x.

- Li Y, Wang X, Blau DM, Caballero MT, Feikin DR, Gill CJ, Madhi SA, Omer SB, Simões EAF, Campbell H. et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2047–64. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00478-0.

- Wildenbeest JG, Billard MN, Zuurbier RP, Korsten K, Langedijk AC, Van de Ven PM, Snape MD, Drysdale SB, Pollard AJ, Robinson H. et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus in healthy term-born infants in Europe: a prospective birth cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;S2213-2600(22):00414–3.

- Riccio MD, Spreeuwenberg P, Osei-Yeboah R, Johannesen CK, Fernandez LV, Teirlinck AC, Wang X, Heikkinen T, Bangert M, Caini S. et al. Burden of respiratory syncytial virus in the European Union: estimation of RSV-associated hospitalizations in children under 5 years. J Infect Dis. 2023;228(11):1528–38. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiad188.

- Grupo de Trabajo utilización de nirsevimab frente a infección por virus respiratorio sincitial de la Ponencia de Programa y Registro de Vacunaciones. Comisión de Salud Pública del Consejo Interterritorial del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Ministerio de Sanidad, julio 2023. Recomendaciones de utilización de nirsevimab frente a virus respiratorio sincitial para la temporada 2023-2024. [cited 2024 Jan 2]. https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/vacunaciones/comoTrabajamos/docs/Nirsevimab.pdf.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Beyfortus® (nirsevimab) - European Public Assessment Report (EPAR). Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/005304/0000.[cited 2024 Jan 4]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/beyfortus-epar-publicassessment-report_en.pdf.

- Drysdake SB, Cathie K, Flamein F, Knuf M, Collins AM, Hill HC, Kaiser F, Cohen R, Pinquier D, Felter CT. et al. Nirsevimab for prevention of hospitalizations due to RSV in infants. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(26):2425–35. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2309189.

- López-Lacort M, Muñoz-Quiles C, Mira-Iglesias A, López-Labrador FX, Mengual-Chuliá B, Fernández-García C, Carballido-Fernández M, Pineda-Caplliure A, Mollar-Maseres J, Shalabi Benavent M. et al. Early estimates of nirsevimab immunoprophylaxis effectiveness against hospital admission for respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infections in infants, Spain, October 2023 to January 2024. ro Surveill. 2024;29(6):2400046. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.6.2400046.

- Ernst C, Bejko D, Gaasch L, Hannelas E, Kahn I, Pierron C, Del Lero N, Schalbar C, Do Carmo E, Kohnen M. et al. Impact of nirsevimab prophylaxis on paediatric respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-related hospitalisations during the initial 2023/24 season in Luxembourg. Euro Surveill. 2024;29(4). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.4.2400033.

- Domachowske JB, Khan AA, Esser MT, Jensen K, Takas T, Villafana T, Dubovsky F, Griffin MP. Safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of MEDI8897, an extended half-life single-dose respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F-targeting monoclonal antibody administered as a single dose to healthy preterm infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37(9):886–92. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000001916.

- Sánchez-Luna M, Manzoni P, Paes B, Baraldi E, Cossey V, Kugelman A, Chawla R, Dotta A, Rodríguez Fernández R, Resch B. et al. Expert consensus on palivizumab use for respiratory syncytial virus in developed countries. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2020;33:35–44. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2018.12.001.

- Figueras Aloy J, Carbonell Estrany X. Comité de Estándares de la SENeo. Update of recommendations on the use of palivizumab as prophylaxis in RSV infections. An Pediatr (Barc). 2015 Mar. 82(3):199.e1–2. doi:10.1016/j.anpedi.2014.10.004.

- Cifras oficiales de población de los municipios españoles en apliación de la Ley de Bases del Régimen Local. Art. 17. Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE); 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 15]. https://www.ine.es/dynt3/inebase/es/index.htm?padre=525.

- Movimiento Natural de la Población: Nacimientos. Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). 2022 [cited 2024 Jan 15]. https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=6518.

- Ezpeleta G, Navascués A, Natividad Viguria N, Herranz-Aguirre M, Juan Belloc SE, Gimeno Ballester J, Muruzábal JC, García-Cenoz M, Trobajo-Sanmartín C, Echeverria A. et al. Effectiveness of nirsevimab immunoprophylaxis administered at birth to prevent infant hospitalisation for respiratory syncytial virus infection: A population-based cohort study. Vaccines (Basel). 2024;12(4):383. doi:10.3390/vaccines12040383.

- Ares-Gómez S, Mallah N, Santiago-Pérez MI, Pardo-Seco J, Pérez-Martínez O, Otero-Barrós M-T, Suárez-Gaiche N, Kramer R, Jin J, Platero-Alonso L. et al. Effectiveness and impact of universal prophylaxis with nirsevimab in infants against hospitalisation for respiratory syncytial virus in Galicia, Spain: initial results of a population-based longitudinal study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024; S1473–3099(24)00215–9. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00215-9.

- Moline HL, Tannis A, Toepfer AP, Williams JV, Boom JA, Englund JA, Halasa NB, Staat MA, Weinberg GA, Selvarangan R. et al. Early estimate of nirsevimab effectiveness for prevention of respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalization among infants entering their first respiratory syncytial virus season - New vaccine surveillance network, October 2023-February 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73(9):209–14.

- Infovac-France. Bulletin n°8 Août - Spécial Nirsevimab et Beyfortus: 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 13]. https://www.infovac.fr/actualites/bulletin-n-8-aout-special-nirsevimab-et-beyfortus.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in Infants and Young Children. 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 13]. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/high-risk/infants-young-children.html#:~:text=RSV%20antibody%20immunization%20is%20recommended,also%20get%20an%20RSV%20antibody.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nirsevimab Receipt and Intent for Infants, U.S. 2024 [cited 2024 Mar 16]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/rsvvaxview/nirsevimab-coverage.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Vaccination Coverage, Pregnant Persons. United States; 2024 [cited 2024 Mar 16]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/rsvvaxview/nirsevimab-coverage.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in Infants and Young Children. 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 16]. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/high-risk/infants-young-children.html#:~:text=RSV%20antibody%20immunization%20is%20recommended,also%20get%20an%20RSV%20antibody.

- Lee Mortensen G, Harrod-Lui K. Parental knowledge about respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and attitudes to infant immunization with monoclonal antibodies. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022;21(10):1523–31. doi:10.1080/14760584.2022.2108799.

- Congedo G, Lombardi GS, Zjalic D, Di Russo M, La Gatta E, Regazzi L, Indolfi G, Staiano A, Cadeddu C. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of a sample of Italian paediatricians towards RSV and its preventive strategies: a cross-sectional study. Ital J Pediatr. 2024;50(1):35. doi:10.1186/s13052-024-01593-1.

- Community preventive services task force. Recommendation for use of immunization information systems to increase vaccination rates. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21(3):249–. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000092.

- Poethko-Müller C, Ellert U, Kuhnert R, Neuhauser H, Schlaud M, Schenk L. Vaccination coverage against measles in German-born and foreign-born children and identification of unvaccinated subgroups in Germany. Vaccine. 2009;27(19):2563–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.009.

- Fabiani M, Fano V, Spadea T, Piovesan C, Bianconi E, Rusciani R, Salamina G, Greco G, Ramigni M, Declich S. et al. Comparison of early childhood vaccination coverage and timeliness between children born to Italian women and those born to foreign women residing in Italy: A multi-centre retrospective cohort study. Vaccine. 2019;37(16):2179–87. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.03.023.

- Pérez-Martín J, Bernal-González PJ, Jiménez-Guillén P, Fernández-Sáez L, Navarro-Alonso JA. Resultados de dos estrategias de captación en la vacunación frente al Virus del PapilomaHumano (VPH) en la Región de Murcia. 2010 [cited 2024 Mar 17]. https://sms.carm.es/ricsmur/bitstream/handle/123456789/2321/bem.2010.30.735.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=.

- euronews.health. Internet]. Lauren Chadwick; c2023 2024 Mar 17]. https://www.euronews.com/health/2023/10/29/stressed-and-very-angry-parents-struggle-to-get-doses-of-new-preventive-rsv-antibody-for-b.

- biopharmadive.com [Internet]. Delilah Alvarado; c2023 [cited 2024 Mar 17]. https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/sanofi-beyfortus-rsv-antibody-shortage/697731/.