?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study aimed to assess the attitudes and willingness of pregnant women to receive the influenza vaccine and the factors influencing their decisions. A sample survey was conducted among pregnant women receiving prenatal care at various medical institutions in Minhang District, Shanghai, from March to June 2023. The survey included inquiries about demographic information, knowledge, and perception of influenza disease and influenza vaccine. Logistic regression models and chi-square tests were used to analyze the data. 6.9% (78/1125) of participants considered receiving the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. Participants with graduate education or above (OR = 4.632, 95%CI: 1.046–20.517), non-office workers (OR = 2.784, 95%CI: 1.560–4.970), and participants whose spouses were not office workers (OR = 0.518, 95% CI: 0.294–0.913) were significantly associated with high intent to vaccinate. Participants with superior knowledge (>30 points) exhibited greater willingness (p < .001). Participants who viewed post-influenza symptoms as mild had a significantly lower willingness to vaccinate during pregnancy (2.3%), compared to those who disagreed (p = .015). Conversely, those recognizing a heightened risk of hospitalization due to respiratory diseases in pregnant women post-influenza were significantly more inclined to vaccinate during pregnancy (8.8%) (p = .007). Participants recognizing benefits uniformly expressed willingness to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy (p < .001), while those perceiving barriers uniformly rejected vaccination (p < .001). Higher education, non-office worker status, and having an office worker spouse correlate with greater willingness to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. Enhanced knowledge and accurate perceptions of influenza and its vaccine influenced willingness. Accumulating knowledge about influenza and its vaccine fosters accurate perceptions. Notably, overall willingness to vaccinate during pregnancy remains low, likely due to safety concerns, and lack of accurate perceptions. Targeted health education, improved communication between healthcare providers and pregnant women, and campaigns highlighting vaccine benefits for mothers and children are essential.

Introduction

Influenza, a viral infection of the respiratory tract, is caused by the influenza virus. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are approximately 1 billion cases of seasonal influenza globally each year, including 3 to 5 million severe cases.Citation1 Elevated infection rates can result in increased hospitalizations and mortality, particularly during periods of heightened influenza activity. For example, in 2017, influenza was linked to at least 650,000 fatalities worldwide.Citation2 Vulnerable groups include the elderly (>65 years old), children under 5 years old, immunocompromised individuals, healthcare workers, and pregnant women.Citation3 Pregnant women, due to physiological and immunological changes, face a 17.3 times higher risk of hospitalization after contracting the influenza virus compared to non-pregnant women. Additionally, pregnant women are at a higher risk for severe morbidity and mortality, with potential complications including miscarriage, preterm labor, and stillbirth.Citation4–6

Influenza vaccination is recognized as the most effective and secure intervention for the prevention of influenza onset and its transmission. Between 2019 and 2020, it is estimated that vaccination averted approximately 7.5 million cases of influenza, 3.7 million medical consultations, 105,000 hospital admissions, and 6,300 fatalities on a global scale.Citation7 In light of these benefits, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) advocates for the routine administration of seasonal influenza vaccines to safeguard high-risk demographics that are more vulnerable to the disease.Citation8 Empirical research has demonstrated that influenza immunization during pregnancy not only significantly mitigates the risk of influenza in expectant mothers but also confers passive immunity to the fetus through the transference of maternal antibodies produced in response to the vaccine across the placenta. This maternal immunization strategy is currently considered the most efficacious approach for the prevention and management of influenza in infants under six months of age, who are not eligible for direct influenza vaccination.Citation3,Citation9 In 2014, the Chinese Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (CACIP) revised its guidelines to prioritize influenza vaccination for pregnant women within its immunization recommendations.

In China, currently approved influenza vaccines for market use encompass trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV3), quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV4), and trivalent live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV3). IIV3 comprises split-virus vaccines and subunit vaccines, while IIV4 consists of split-virus vaccines, and LAIV3 is a live attenuated vaccine. Despite clear guidelines in China’s annual influenza vaccine technical guidelines advocating for timely influenza vaccination among pregnant women as a high-risk group, challenges such as the categorization of pregnant women as contraindications in certain domestic influenza vaccine product instructions and entrenched traditional beliefs have impeded influenza vaccination uptake among pregnant women in China. This study aimed to assess pregnant women’s knowledge, awareness, and willingness to receive influenza vaccine on influenza and influenza vaccine. It delved into exploring the factors influencing pregnant women’s willingness to be vaccinated against influenza, aiming to provide evidence for policymakers to further increase influenza vaccination rates among pregnant women.

Methods

Study participants

This study included pregnant women who underwent prenatal examinations at hospitals in Minhang District, Shanghai, between March 1 and June 20, 2023. Based on the formula for calculating sample size in cross-sectional surveys, , and referencing a study on the willingness of pregnant women in Beijing to receive influenza vaccination,Citation10 with

= 11.4%, α = 0.05 (Z1−α/2 = 1.96), and an acceptable margin of error d = 0.20p, factoring in a 20% non-response rate, the estimated total minimum sample size required was 934 cases.

Survey method

A questionnaire was designed by the Minhang District Center for Disease Control and Prevention (referred to as “District CDC”). The questionnaire was adapted and modified from questions previously published in the literature, and translated into Chinese.Citation11–13 Utilizing a convenience sampling survey methodology, the questionnaire was disseminated among pregnant women who were attending antenatal care or undergoing prenatal examinations at a variety of healthcare facilities within the jurisdiction of Minhang District. Prior to the distribution of the questionnaires, a uniform training session on the survey’s content was conducted by the District CDC for the healthcare personnel at each participating medical institution to ensure consistency in administration. Eligible participants were invited to complete the questionnaire by scanning a Quick Response (QR) code, following the provision of informed consent. By June 20, 2023, a cumulative total of 1189 electronic questionnaires had been submitted, with 1125 of these being deemed valid for analysis after a thorough review and validation process to ensure the integrity and reliability of the collected data.

Survey content

The questionnaire consisted of three parts: “Basic Information,” “Knowledge of Influenza Virus and Influenza Vaccine,” and “Perception of Influenza Vaccine Administration.” Following Anderson’s health behavior model, factors influencing pregnant women’s willingness to receive influenza vaccination were categorized into four types:

Predisposing factors: Age, household registration, educational level, spouse’s educational level, occupation, spouse’s occupation, parity.

Enabling resources: The level of the last medical institution visited, household income per capita, and recommendations by others.

Need factors: Health condition, whether the estimated due date falls within the flu season, whether there are contraindications to vaccination, and whether there is a charge for the vaccine.

Health behaviors: Family history of influenza vaccination, personal history of influenza vaccination.

The “Knowledge of Influenza Virus and Influenza Vaccine” section comprised 7 questions, each scored out of 10, with a total score of 70. The “Perception of Influenza Vaccine Administration” included:

Perceived barriers to influenza vaccine administration: Unaware that pregnant women are eligible to receive the influenza vaccine, receiving the influenza vaccine may harm the fetus.

Perceived benefits of influenza vaccine administration: Reducing the spread of influenza virus within the family, transferring antibodies to the fetus through maternal vaccination, enhancing resistance to prevent influenza during pregnancy.

Perception of the severity of influenza in pregnant women: Perception of mild symptoms after influenza infection, belief that influenza infection has minimal impact on the fetus, perception of similar hospitalization rates for respiratory diseases between pregnant and non-pregnant women, increased risk of complications after infection, increased risk of low birth weight in infants, increased risk of respiratory-related hospitalization in pregnant women after infection.

Statistical analysis

Data collection was performed using Excel 2022 software, and statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 24.0 software. For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages were reported. The median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to summarize continuous variables. Chi-square tests were used to compare rates. To comprehensively and objectively analyze factors influencing pregnant women’s willingness to receive influenza vaccination, forward stepwise logistic regression analysis was employed. Predisposing factors were included as control variables in Model 1; Model 2 added enabling resources to Model 1; Model 3 added need factors to Model 2; Model 4 added health behaviors to Model 3. Factors without confidence intervals were excluded. Furthermore, the association between pregnant women’s knowledge of influenza and the influenza vaccine and their perception of influenza vaccine administration was examined using single-factor logistic regression analysis, with perception serving as the dependent variable and knowledge as the independent variable. A significance level of p < .05 was adopted to denote statistical significance.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Minhang District Center for Disease Control and Prevention under EC-P-2020-010.

Results

Willingness of pregnant women to receive influenza vaccination during pregnancy

A total of 1125 valid questionnaires were collected. The majority of participants were non-local residents (77.7%; 874/1125), had no underlying diseases (97.4%; 1096/1125), and had never received influenza vaccination before (76.4%; 859/1125).

Of significance, a striking 93.1% (1047/1125) of participants expressed reluctance toward receiving the influenza vaccine during pregnancy, with only a marginal 6.9% (78/1125) considering vaccination during this period.

Analysis of factors influencing pregnant women’s willingness to receive influenza vaccination during pregnancy

The educational level, occupation type, and spouse’s occupation type of pregnant women had certain influences on their willingness to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. As the educational level of the participants increased, there was a corresponding increase in the proportion willing to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy, with rates of 3.3% (5/153) for those with junior high school education or below, 5.9% (21/432) for those with high school/diploma education, 8.2% (34/415) for those with undergraduate education, and 14.4% (18/125) for those with graduate education or above. Among participants employed in office settings, 6.4% (35/546) expressed willingness to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy, which was higher than the 7.4% (43/579) observed among those in non-office occupations. Similarly, among participants whose spouses were employed in office settings, 9.1% (46/504) were willing to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy, compared to 5.2% (32/621) among those whose spouses were employed in non-office occupations. Furthermore, participants who received recommendations from others all accepted influenza vaccination during pregnancy, whereas among those who had not received recommendations, only 4.9% (54/1101) expressed willingness to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. Moreover, among participants whose family members or cohabitants had received influenza vaccination before, 9.2% (27/293) were willing to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy, while among those whose family members or cohabitants had never received influenza vaccination, the proportion willing to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy was 6.1% (51/832) (.

Table 1. Factors influencing pregnant women's willingness to receive influenza vaccination during pregnancy using multivariable logistic regression.

Further analysis revealed that Cox Snell R2, Nagelkerke R2, and χ2 gradually increased, indicating that with the introduction of enabling resources, need factors, and health behaviors, the explanatory power and goodness of fit of the model gradually improved. Therefore, the interpretation of the results was based on Model 4. Specifically, the educational level of participants, their occupation type, and their spouse’s occupation type were significantly associated with pregnant women’s willingness to receive influenza vaccination during pregnancy (p < .05). As the educational level of the participants increased, their willingness to receive influenza vaccination during pregnancy increased. Compared to participants with junior high school education or below, those with graduate education or above had a higher willingness to receive vaccination (OR = 4.632, 95%CI: 1.046–20.517). Furthermore, participants in non-office occupations exhibited a greater willingness to receive vaccination compared to those in office occupations (OR = 2.784, 95%CI: 1.560–4.970). Additionally, participants whose spouses were in non-office occupations displayed a lower willingness to receive vaccination compared to those whose spouses were in office occupations (OR = 0.518, 95%CI: 0.294–0.913).

Knowledge about influenza and influenza vaccination among pregnant women

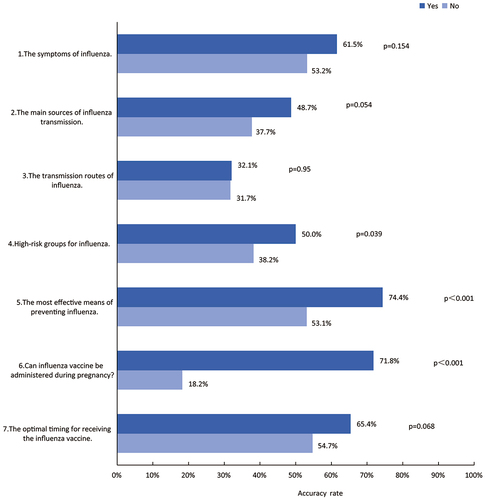

The average accuracy rate for the seven questions was 42.1%, ranging from a high of 55.5% to a low of 22.0%. Particularly, participants demonstrated the highest accuracy rate in answering Question 7, achieving 55.5% accuracy (65.4% among those willing to vaccinate, 54.7% among those unwilling), whereas Question 6 had the lowest accuracy rate (71.8% among those willing to vaccinate, 18.2% among those unwilling). Participants who expressed willingness to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy exhibited higher accuracy rates in answering all seven questions compared to those who were unwilling. Specifically, among participants willing to vaccinate, the proportions correctly answering Questions 4, 5, and 6 were 11.8%, 21.3%, and 53.6% higher, respectively, than among those unwilling (p < .05) ().

Figure 1. Accuracy rate of influenza and influenza vaccine-related knowledge among pregnant women. This bar chart illustrates the correct rates for seven questions related to influenza and influenza vaccine knowledge among pregnant women. Each question is grouped based on whether the participant has the willingness to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy: those willing to receive (dark blue bars) and those not willing to receive (light blue bars).

The median (IQR) knowledge score for participants was 30 (20–40), with 63.3% (712/1125) scoring ≤ 30 and 36.7% (413/1125) scoring > 30. Among participants willing to vaccinate, 62.8% (49/78) scored > 30, significantly higher than among those unwilling (34.8%, 364/1047) (p < .001).

Pregnant women’s perception of influenza vaccine during pregnancy

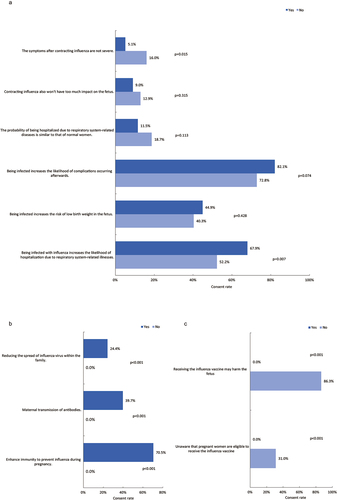

Only a small fraction of participants (15.3%, 172/1125) agreed that the symptoms following influenza infection are not severe (). Among those in agreement, merely 2.3% (4/172) expressed willingness to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. Conversely, among those who disagreed, 7.8% (74/953) were inclined to receive the vaccine during pregnancy, significantly higher than those in agreement (p = .015). Furthermore, among those who acknowledged that being infected with influenza increases the likelihood of hospitalization due to respiratory system-related illnesses, 8.8% (53/600) were open to receiving the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. In contrast, among those who disagreed, only 4.8% (25/525) expressed willingness to receive the vaccine during pregnancy, significantly lower than those who agreed (p = .007).

Figure 2. Consent rate among pregnant women regarding their perceptions of influenza vaccination. This figure illustrates the agreement rates for eleven cognitive questions regarding influenza vaccine administration among pregnant women. It is divided into three parts: A (perception of severity), B (perception of benefits), and C (perception of barriers). Each question is grouped based on whether participants are willing to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy: those willing to vaccinate (dark blue bars) and those unwilling to vaccinate (light blue bars).

Among participants willing to receive the vaccine, a notable proportion believed that it could transfer antibodies to the fetus (39.7%, 31/78), enhance immunity (70.5%, 55/78), and reduce the spread of influenza virus within the family (24.4%, 19/78). These figures were significantly higher than among those unwilling to receive the vaccine (p < .001) (). Conversely, among participants disinclined to receive the vaccine, the majority (86.3%, 904/1047) harbored concerns that receiving the influenza vaccine may harm the fetus, 31.0% (325/1047) were unaware that pregnant women are eligible to receive the influenza vaccine, significantly higher than those with a willingness to receive the vaccine (p < .001) ().

The findings from suggested that participants with higher knowledge scores were more inclined to endorse several viewpoints. They were more likely to agree that contracting influenza increases the risk of low birth weight in infants (OR = 1.326, 95%CI: 1.228–1.433), raises the likelihood of hospitalization due to respiratory system-related illnesses (OR = 1.445, 95%CI: 1.333–1.565), and that the influenza vaccine can effectively reduce the spread of the virus within the family (OR = 1.619, 95%CI: 1.217–2.153). Additionally, they tended to acknowledge that the vaccine can pass antibodies to the fetus (OR = 1.579, 95%CI: 1.261–1.976) and enhance immunity to prevent influenza during pregnancy (OR = 1.565, 95%CI: 1.318–1.859). However, they were less likely to believe that being infected increases the likelihood of complications occurring afterward (OR = 0.783, 95%CI: 0.718–0.853).

Table 2. Correlation between pregnant women’s knowledge of influenza and influenza vaccines and the perceptions of influenza vaccination.

Discussion

This study unveiled that merely 6.9% of pregnant women displayed a willingness to consider influenza vaccination during pregnancy.Citation14 This figure falls significantly below rates observed in other developed nations such as the United States,Citation15 as well as below those reported in regions like Beijing (11.4%)Citation10 and Zhejiang Province (76.3%).Citation16 These discrepancies suggest potential regional variations linked to residents’ awareness levels regarding vaccines, promotional strategies, vaccine accessibility, and other influencing factors. Even among those with graduate education or higher, only 14.4% were willing to receive the flu vaccine during pregnancy. This suggests that higher education alone may not suffice in overcoming barriers to vaccination. Several factors contribute to this, including limited awareness about the eligibility and benefits of the influenza vaccine, concerns about vaccine safety, and traditional beliefs. To address these issues, targeted education campaigns are essential.Citation17 These campaigns should focus on disseminating accurate information about the safety and efficacy of influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Healthcare providers play a pivotal role and should be equipped with the necessary resources to educate and reassure pregnant women.Citation18

The results of the multivariable analysis showed a significant association between vaccination willingness and participants’ educational level, as well as the occupational types of both participants and their spouses. As participants’ educational levels increased, so did their willingness to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. This trend suggests that women with higher educational achievements are more likely to be cognizant of the risks posed by influenza during pregnancy and harbor a favorable attitude toward the effectiveness of vaccination during this critical period. A study conducted in Italy revealed that compared to participants with university degrees or higher, those with junior high school education or below displayed a diminished willingness to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy (p = .004).Citation19 Similar conclusions were drawn in a study by Bödeker et al. in 2015.Citation20 Moreover, participants engaged in non-office occupations demonstrated a heightened inclination toward vaccination compared to those with office jobs. Conversely, participants whose spouses were engaged in non-office occupations exhibited a diminished inclination toward vaccination compared to those whose spouses held office jobs. While no analogous studies offer definitive explanations, it is plausible that the occupational statuses of individuals and their spouses may influence their attitudes and behaviors toward vaccination through various pathways, including direct impacts on exposure risk, influence on health awareness and knowledge levels, and dynamics within the household environment. Subsequent research endeavors should strive to categorize occupational types for more nuanced exploration.

Analysis of influenza and influenza vaccine knowledge survey data revealed that among participants willing to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy, the proportion of correct responses about high-risk groups for influenza, the most effective preventive measures for influenza, and the permissibility of influenza vaccination for pregnant women was significantly higher than among those unwilling to vaccinate. This suggests that a comprehensive understanding of influenza and influenza vaccine knowledge can bolster individuals’ confidence in vaccines and engender proactive measures to shield themselves from influenza. Furthermore, results indicated that participants with knowledge scores exceeding 30 were more willing to receive vaccination. This aligns with prior research, underscoring that an enhanced understanding of diseases and vaccines can augment vaccination uptake.Citation21,Citation22 Presently, studies exploring vaccination willingness and vaccine hesitancy increasingly emphasize the concept of vaccine literacy.Citation23 Defined as an extension of vaccine knowledge, vaccine literacy denotes individuals’ capacity to acquire, assimilate, and comprehend fundamental vaccine-related information and services, as well as their ability to weigh the risks and benefits of vaccination decisions in the context of their overall health.Citation24 Future research endeavors should delve deeper into understanding pregnant women’s perspectives, drawing upon the foundational tenets of vaccine literacy.

Our study found that while 36.7% of participants had a knowledge score greater than 30, this did not translate into higher willingness to vaccinate. This could be attributed to the traditional Chinese cultural notions surrounding pregnancy taboos, making it difficult for individuals to translate knowledge into behavior. To bridge this gap, more interactive and engaging educational initiatives are needed. These initiatives might encompass personalized one-on-one counseling sessions, as well as leveraging digital media to disseminate information effectively.Citation25,Citation26 Healthcare providers should be trained to address common concerns and misconceptions, emphasizing the vaccine’s benefits for both the mother and the fetus.Citation18 Additionally, leveraging community engagement could help change attitudes toward vaccination.Citation27 By creating a supportive environment and addressing specific fears and misconceptions, it may be possible to improve pregnant women’s willingness to be vaccinated.

The cognitive survey results showed that among participants who agreed that pregnant women are more likely to be hospitalized due to respiratory diseases after contracting influenza, the proportion willing to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy was significantly higher than among those who disagreed. Among participants with a willingness to vaccinate, the proportions believing that it can pass antibodies to the fetus, enhance immunity, and reduce the spread of influenza virus in the family were significantly higher than among those without a willingness to vaccinate. The study by Ditsungnoe et al.Citation11 revealed that among pregnant women willing to receive the vaccine, perceptions of influenza severity (p = .001) and the vaccine’s benefits for both themselves and their fetuses (p < .001) were higher than those unwilling to receive it. Otieno et al.Citation28 found that participants agreeing to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy showed a higher willingness to protect infants from influenza virus infection (OR = 2.37; 95%CI = 1.27–4.43). These results align with our study. Furthermore, our study revealed that among participants unwilling to vaccinate, there was a significantly higher proportion believing that receiving the influenza vaccine would have adverse effects on the fetus, and many were unaware that pregnant women could receive the influenza vaccine, compared to those willing to vaccinate. These findings are in line with other studies on influenza vaccine hesitancy.Citation11,Citation29 A study in Thailand showed that moderate (PR = 0.5, 95%CI = 0.4–0.7) and high (PR = 0.5, 95%CI = 0.4–0.8) perceived barriers were negatively correlated with vaccination willingness.Citation11 A domestic study highlighted concerns about side effects (48%) and potential impacts on the fetus (35.6%) as the main factors contributing to vaccine hesitancy.Citation30 Similarly, a study in Poland reported that among pregnant women declining the influenza vaccine, 53.8% expressed concerns about adverse effects on the fetus.Citation31 A 2019 study in Greece also yielded similar conclusions.Citation32 Hence, it is imperative to emphasize the promotion of influenza and influenza vaccine awareness, along with the collection and analysis of data on influenza vaccine safety during pregnancy in China.

Moreover, the study revealed that participants with higher levels of knowledge about influenza and influenza vaccines were more inclined to acknowledge that contracting influenza could heighten the risk of low birth weight in infants, respiratory disease-related hospitalizations, reduce the transmission of influenza virus within the family, convey antibodies to the fetus, and bolster immunity to prevent influenza during pregnancy. However, they were less likely to agree that complications were more likely to occur after influenza infection. This underscores how the accumulation of knowledge about influenza and influenza vaccines contributes to fostering accurate perceptions regarding them. The cognitive differences theory suggests that individuals differ in their processing and understanding of information.Citation33 Therefore, a possible explanation for these results is that the accumulation of knowledge on influenza and influenza vaccines can reduce cognitive differences, leading individuals to more uniformly understand related issues, thereby forming consistent correct perceptions.

Currently, there is limited research on the willingness of pregnant women in China to receive influenza vaccination, as well as their knowledge and perceptions related to it. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct pertinent surveys. The Anderson’s health behavior model, developed in Western countries and extensively tested, has gradually been employed to explain healthcare decision-making behaviors.Citation34–36 This study represents the first to utilize the Anderson’s model to analyze key factors influencing willingness to receive influenza vaccination during pregnancy.

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, this study was conducted in a medical environment, so our results may be subject to selection bias. Secondly, the survey only used closed-ended questionnaires without including focus group interviews or open-ended questions. Thirdly, the study was cross-sectional and used convenience sampling, affecting sample representativeness. Future research could employ cluster or stratified sampling for a more comprehensive analysis of pregnant women’s willingness for influenza vaccination and its influencing factors. In addition, this study only assessed participants’ willingness to accept influenza vaccination but did not track their vaccination status. Therefore, the actual vaccination rate cannot be estimated.

Conclusion

In this study, only 6.9% of pregnant women were willing to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. Analysis revealed a significant association between higher education levels, non-office worker status, and having a spouse who is an office worker with a greater willingness to receive the vaccine. Additionally, knowledge and perception of influenza and its vaccine were key factors influencing vaccine acceptance during pregnancy. Accumulating knowledge about influenza and its vaccine contributes to the establishment of accurate perceptions. Enhanced educational and communication strategies targeting pregnant women and their families are warranted. Subsequent phases of this research will involve focus groups and interviews to further explore attitudes and facilitating factors related to influenza vaccine acceptance during pregnancy.

Authors’ contributions

JL designed the study described in this article. YL and LX conducted the investigation and participated in data collection, and JL oversaw all aspects of data collocation. YL and XF were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data. YL and XF were responsible for drafting the manuscript and JL revised it critically for intellectual content. All authors approved the final versions to be published, and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the respondents completed the questionnaire.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Influenza (Seasonal): World Health Organization.[cited 2024 Apr 20]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal).

- Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, Muscatello DJ, Palekar R, Tempia S, Cohen C, Gran JM, Schanzer D, Cowling BJ, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1285–10. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)33293-2.

- Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Uyeki TM. Effects of influenza on pregnant women and infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(3 Suppl):S3–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.068.

- Somerville LK, Basile K, Dwyer DE, Kok J. The impact of influenza virus infection in pregnancy. Future Microbiol. 2018;13(2):263–74. doi:10.2217/fmb-2017-0096.

- Brydak LB, Nitsch-Osuch A. Vaccination against influenza in pregnant women. Acta Biochim Pol. 2014;61(3):589–91. doi:10.18388/abp.2014_1880.

- Beigi RH. Influenza during pregnancy: a cause of serious infection in obstetrics. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(4):914–26. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e31827146bd.

- Global Influenza Strategy 2019–2030: World Health Organization. [cited 2024 Apr 20]. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/311184/9789241515320-eng.pdf?sequence=18.

- Oakley S, Bouchet J, Costello P, Parker J. Influenza vaccine uptake among at-risk adults (aged 16–64 years) in the UK: a retrospective database analysis. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1734. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11736-2.

- Poehling KA, Szilagyi PG, Staat MA, Snively BM, Payne DC, Bridges CB, Chu SY, Light LS, Prill MM, Finelli L, et al. Impact of maternal immunization on influenza hospitalizations in infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(Suppl 6):S141–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.042.

- Wang J, Sun D, Abudusaimaiti X, Vermund SH, Li D, Hu Y. Low awareness of influenza vaccination among pregnant women and their obstetricians: a population-based survey in Beijing, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(11):2637–43. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1596713.

- Ditsungnoen D, Greenbaum A, Praphasiri P, Dawood FS, Thompson MG, Yoocharoen P, Lindblade KA, Olsen SJ, Muangchana C. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs related to seasonal influenza vaccine among pregnant women in Thailand. Vaccine. 2016;34(18):2141–6. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.056.

- Gu W, Liu Y, Chen Q, Wang J, Che X, Du J, Zhang X, Xu Y, Zhang X, Jiang W, et al. Acceptance of influenza vaccination and associated factors among teachers in China: a cross-sectional study based on health belief model. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(3):2270325. doi:10.1080/21645515.2023.2270325.

- Lin W, Yin W, Yuan D. Factors associated with the utilization of community-based health services among older adults in China-an empirical study based on Anderson’s health behavior model. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):99. doi:10.1186/s12875-022-01697-9.

- Pavlasová L, Vojíř K. Influenza and influenza vaccination from the perspective of Czech pre-service teachers: knowledge and attitudes. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2021;29(3):177–82. doi:10.21101/cejph.a6670.

- Ding H, Black CL, Ball S, Fink RV, Williams WW, Fiebelkorn AP, Lu P-J, Kahn KE, D’Angelo DV, Devlin R, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women — United States, 2016–17 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(38):1016–22. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6638a2.

- Hu Y, Wang Y, Liang H, Chen Y. Seasonal influenza vaccine acceptance among pregnant women in Zhejiang Province, China: evidence based on health belief model. Int J Environ Res And Public Health. 2017;14(12):1551. doi:10.3390/ijerph14121551.

- Zhou S, Greene CM, Song Y, Zhang R, Rodewald LE, Feng L, Millman AJ. Review of the status and challenges associated with increasing influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(3):602–11. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1664230.

- Nawabi F, Krebs F, Vennedey V, Shukri A, Lorenz L, Stock S. Health literacy in pregnant women: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res And Public Health. 2021;18(7):3847. doi:10.3390/ijerph18073847.

- Napolitano F, Napolitano P, Angelillo IF. Seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnant women: knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):48. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-2138-2.

- Bödeker B, Betsch C, Wichmann O. Skewed risk perceptions in pregnant women: the case of influenza vaccination. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1308. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2621-5.

- Ganczak M, Kalinowski P, Drozd-Dąbrowska M, Biesiada D, Dubiel P, Topczewska K, Molas-Biesiada A, Oszutowska-Mazurek D, Korzeń M. School life and influenza immunization: a cross-sectional study on vaccination coverage and influencing determinants among polish teachers. Vaccine. 2020;38(34):5548–55. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.067.

- Abdullahi LH, Kagina BM, Cassidy T, Adebayo EF, Wiysonge CS, Hussey GD. Knowledge, attitudes and practices on adolescent vaccination among adolescents, parents and teachers in Africa: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2016;34(34):3950–60. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.023.

- Zhang E, Dai Z, Wang S, Wang X, Zhang X, Fang Q. Vaccine literacy and vaccination: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2023;68:1605606. doi:10.3389/ijph.2023.1605606.

- Ratzan SC. Vaccine literacy: a new shot for advancing health. J Health Commun. 2011;16(3):227–9. doi:10.1080/10810730.2011.561726.

- Li P, Hayat K, Jiang M, Pu Z, Yao X, Zou Y, Lambojon K, Huang Y, Hua J, Xiao H, et al. Impact of video-led educational intervention on the uptake of influenza vaccine among adults aged 60 years and above in China: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):222. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10220-1.

- Opel DJ, Zhou C, Robinson JD, Henrikson N, Lepere K, Mangione-Smith R, Taylor JA. Impact of childhood vaccine discussion format over time on immunization status. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(4):430–6. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.12.009.

- Guan H, Zhang L, Chen X, Zhang Y, Ding Y, Liu W. Enhancing vaccination uptake through community engagement: evidence from China. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):10845. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-61583-5.

- Otieno NA, Nyawanda B, Otiato F, Adero M, Wairimu WN, Atito R, Wilson AD, Gonzalez-Casanova I, Malik FA, Verani JR, et al. Knowledge and attitudes towards influenza and influenza vaccination among pregnant women in Kenya. Vaccine. 2020;38(43):6832–8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.015.

- Mayet AY, Al-Shaikh GK, Al-Mandeel HM, Alsaleh, NA and Hamad, AF. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and barriers associated with the uptake of influenza vaccine among pregnant women. Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25(1):76–82. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2015.12.001.

- Wang R, Tao L, Han N, Liu J, Yuan C, Deng L, Han C, Sun F, Chi L, Liu M, et al. Acceptance of seasonal influenza vaccination and associated factors among pregnant women in the context of COVID-19 pandemic in China: a multi-center cross-sectional study based on health belief model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):745. doi:10.1186/s12884-021-04224-3.

- Pisula A, Sienicka A, Pawlik KK, Dobrowolska-Redo A, Kacperczyk-Bartnik J, Romejko-Wolniewicz E. Pregnant women’s knowledge of and attitudes towards influenza vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. Int J Environ Res And Public Health. 2022;19(8):4504. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084504.

- Maltezou HC, Pelopidas Koutroumanis P, Kritikopoulou C, Theodoridou K, Katerelos P, Tsiaousi I, Rodolakis A, Loutradis D. Knowledge about influenza and adherence to the recommendations for influenza vaccination of pregnant women after an educational intervention in Greece. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(5):1070–4. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1568158.

- Draycott S, Dabbs A. Cognitive dissonance. 1: an overview of the literature and its integration into theory and practice in clinical psychology. Br J Clin Psychol. 1998;37(3):341–53. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8260.1998.tb01390.x.

- Broyles RW, Narine L, Brandt EN Jr., Biard-Holmes D. Health risks, ability to pay, and the use of primary care: is the distribution of service effective and equitable? Prev Med. 2000;30(6):453–62. doi:10.1006/pmed.2000.0672.

- Green SE. The impact of stigma on maternal attitudes toward placement of children with disabilities in residential care facilities. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(4):799–812. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.023.

- Sunil TS, Rajaram S, Zottarelli LK. Do individual and program factors matter in the utilization of maternal care services in rural India?: a theoretical approach. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(8):1943–57. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.09.004.