ABSTRACT

Multiple studies have documented low human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake among Chinese girls. It remains crucial to determine the parental willingness to pay (WTP) HPV vaccine for girls. We conducted a cross-sectional study recruiting 3904 parents with girls aged 9–14 in Shanghai, China, employing an online questionnaire with a convenience sampling strategy. Parental WTP, both range of payment and estimated point value, were determined for themselves (or wives) and daughters. HPV vaccine uptake was 22.44% in mothers and 3.21% in daughters. Respondents favored WTP ≤ 1000 CNY/138 USD for themselves (or wives), whereas showed increasing WTP along with valency of HPV vaccine for daughters (2-valent: 68.62% ≤1000 CNY/138 USD; 4-valent: 56.27% 1001–2000 CNY/138–277 USD; 9-valent: 65.37% ≥2001 CNY/277 USD). Overall, respondents showed higher WTP for daughters (median 2000 CNY/277 USD; IQR 1000–3600 CNY/138–498 USD) than for themselves (2000 CNY/277 USD; 1000–3500 CNY/138–483 USD) or wives (2000 CNY/277 USD; 800–3000 CNY/110–414 USD) (each p < .05). Furthermore, parental WTP was higher for international vaccine and 9-valent vaccine (each p < 0.05). Between two assumed government subsidy scenarios, parental preference for 9-valent vaccine remained consistently high for daughters (approximately 24% in each scenario), whereas preference for themselves (or wives) was sensitive to payment change between the subsidy scenarios. Using a discrete choice experiment, we found domestic vaccine was commonly preferred; however, certain sociodemographic groups preferred multivalent HPV vaccines. In conclusion, the valency of HPV vaccine may influence parental decision-making for daughters, in addition to vaccine price. Our findings would facilitate tailoring the HPV immunization program in China.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination is crucial to prevent diseases related to HPV infection, including genital warts, cervical cancer, and other cancers.Citation1,Citation2 Studies have proven that HPV vaccine is safe for girls and adolescent women.Citation3,Citation4 In China, previous studies reported low incidence of adverse events following HPV immunization.Citation5,Citation6 Moreover, HPV vaccination in girls and adolescent women can significantly reduce the incidence of HPV infection, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), and, subsequently, cervical cancer.Citation7–9 In addition, the economic evaluation suggested HPV vaccination in those girls and adolescent women has good cost-effectiveness or cost-benefit.Citation10

Currently, five types of HPV vaccines are available in China for women aged 9–45, including 2-valent, 4-valent, and 9-valent vaccines of international manufacturers and two types of 2-valent vaccines of domestic manufacturers.Citation11 However, HPV vaccine uptake has remained substantially low among Chinese women, especially in girls in middle and elementary schools, which is estimated to be 2.24%.Citation12 Similarly, some Asian countries such as Japan and Singapore have low uptake of HPV vaccine in girls.Citation13–15 In Asia, the perceived safety and necessity of HPV vaccination for girls usually influence parental intent.Citation16,Citation17 Higher vaccine price is also an obstacle to HPV vaccination, even in high-income countries and regions.Citation17,Citation18 In China, the high price of HPV vaccine is highly influential in the parental decision-making of HPV vaccination for their daughters aged ≤ 18.Citation19,Citation20 Thus, it remains crucial to understand the parental demand and preference for their daughters about HPV vaccine, in comparison with those for parents themselves.

Shanghai is one of the most economically developed metropolises in China. Parents in Shanghai have a relatively high intent to accept HPV vaccination for their daughters.Citation21 However, HPV vaccine uptake remains low in girls. Since 2020, multiple cities in China have implemented pilot programs of HPV immunization targeting girls aged 9–14, primarily in elementary and middle schools.Citation22 In the meantime, government subsidy mechanisms have been designed to reduce parental out-of-pocket costs and promote vaccination behavior. However, a pilot program of HPV immunization has not yet been implemented in Shanghai until 2023. Thus, it may be necessary to determine whether those subsidy mechanisms would be effective in increasing parental intent to accept HPV vaccine or willingness to pay (WTP) HPV vaccine for girls. This study aimed to investigate the HPV vaccination status among mothers and their daughters and identify parental WTP and preference for HPV vaccine for themselves and their daughters in Shanghai. The findings from the study would provide more evidence for tailoring HPV immunization programs, including possible subsidy strategies, for girls aged 9–14 in metropolis regions in China.

Materials and methods

Study design

We designed a cross-sectional study to recruit parents (including mothers and fathers) with daughter (s) aged 9–14 in Shanghai from January through August 2022. We used an online questionnaire (www.wjx.com) to investigate the HPV vaccination status among mothers and daughters and parental WTP HPV vaccine for themselves (or their wives) and their daughters. We randomly selected 8 districts in a total of 16 districts in Shanghai municipality. Following a convenience sampling strategy, we distributed the online questionnaire to the parents in the elementary and middle schools in these 8 districts.

Our study employed a single-population proportion formula to determine the minimum sample size, assuming 60% of parents would accept the HPV vaccine. Accordingly, with a 95% confidence interval and a 5% margin of error, each district required a minimum sample size of 320 respondents, resulting in a total sample size of at least 2560 respondents for the study.

Survey instrument

The questionnaire primarily consisted of questions on socio-demographic status, HPV vaccination status and willingness, WTP, and preference selection. The questionnaire was designed with a panel of public health practitioners and researchers, including public health practitioners in municipal and district CDCs (n = 4) and POVs (n = 3), statistician (n = 1), behavioral psychologist (n = 1), gynecologist (n = 1), pediatrician (n = 1) and principal investigator (n = 1). Specifically, the experts in the panel carefully revised the questionnaire in Standard Mandarin, ensuring that each question was aligned with the theoretical constructs and measurements were appropriate for data analysis. Then, a pilot survey was conducted among 50 local parents with girls aged 9–14 (80% were mothers) recruited by convenience sampling to assess the effectiveness of bid valuation and validate the questions. The Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.92, the KMO coefficient was 0.90, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < .001), indicating good reliability and validity of the questionnaire.

HPV vaccination status among mothers and their daughters

In the questionnaire, we investigated the HPV vaccination status (uptake and intent) among parents themselves (or their wives) and their daughters. A total of four responses were prepared, including “had been vaccinated,” “had not been vaccinated but had made an appointment,” “intended to accept HPV vaccination but had not made an appointment,” and “did not intend to receive HPV vaccination.” Considering the low uptake of HPV vaccine, we collapsed the first two responses together, which indicated HPV vaccine uptake. The third and fourth responses indicated the intent to accept HPV vaccine and no intent to receive HPV vaccine, respectively.

WTP HPV vaccine for parents themselves (or their wives) and their daughters

In the questionnaire, we prepared three ranges of payment (≤1000, 1001–2000, ≥2001 CNY/138, 138–277, 277 USD) covering three doses of HPV vaccine for 2-valent HPV vaccine (2vHPV), 4-valent HPV vaccine (4vHPV), and 9-valent HPV vaccine (9vHPV). Respondents were asked to choose the maximum range of payment they mostly prefer for themselves and for their daughters.

We used the contingent valuation method (CVM) to estimate the point value of parental WTP HPV vaccine for parents themselves and for their daughters. Five sets of questions appeared randomly, with 800, 1600, 2400, 3200, and 4000 CNY/111, 221, 332, 443, and 553 USD as initial WTPs; in each online questionnaire, parents accessed only one set of questions. These amounts were designed as equidistant with reference to current prices of HPV vaccines in China, including domestic and international 2vHPV, international 4vHPV, assumed domestic 9vHPV, and international 9vHPV. Then, a two-boundary dichotomous approach was selected to determine the parental WTP. For example, parents responded to the first question, “If the price of HPV vaccine is 800 CNY/111 USD, would you intend to pay it for your daughter?.” Then, parents responded to the next question, “If the price of HPV vaccine has been increased to 1200 CNY/166 USD, would you intend to pay it for your daughter?” as “yes” to the first question or “If the price of HPV vaccine has been reduced to 400 CNY/55 USD, would you intend to pay it for your daughter” as “no” to the first question. Finally, parents answered an open-ended question about the maximum WTP they mostly prefer for themselves and their daughters.

Preference for HPV vaccine

We further designed a discrete choice experiment (DCE) to determine parental preference for HPV vaccine by providing respondents with a series of selection sets consisting of two competing alternatives (diverse HPV vaccines in our study), as described elsewhere.Citation23

To better simulate actual HPV vaccination, we summarized the current government subsidy mechanisms that have already been implemented in multiple cities in China and then designed the following government subsidy scenarios: scenario 1, “Domestic 2vHPV is freely provided; parents need to pay full price when they choose other HPV vaccines,” and scenario 2, “Domestic 2vHPV is freely provided; parents need to pay the difference in prices when they choose other HPV vaccines.” In both subsidy scenarios, parents were asked about their preference for HPV vaccine for themselves and for their daughters. In each of the two subsidy scenarios, we prepared 10 selection sets, and parents randomly accessed only one set of questions. Attributes and levels (in the parentheses) of HPV vaccines were prepared as follows: valency (2vHPV, 4vHPV, and 9vHPV), manufacturer (domestic and international), and price (in scenario 1: 0, 1800, 2500, 2800, and 3900 CNY/0, 249, 246, 387, and 539 USD, which were actual prices available in China; in scenario 2: 0, 1100, 1800, 2100, and 3200 CNY/0, 152, 249, 290, and 443 USD, which were reduced by 700 CNY/97 USD as amount of subsidy).

Statistical analysis

We compared the parental WTP HPV vaccine for themselves and their daughters across vaccination status using Pearson’s chi-square test. The Kappa test was utilized to determine the agreement between the WTP (range of maximum payment) for parents themselves and their daughters across 2vHPV, 4vHPV, and 9vHPV. The T-test and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test were used to compare the WTP for parents themselves and their daughters. All the above analyses were conducted using R 4.2.1. Significance was assessed at p < 0.05 and adjusted when appropriate using Bonferroni correction. Furthermore, a multilevel, multivariable conditional logistic regression model was constructed to determine the parental preference for HPV vaccine for themselves and their daughters by using the survey logistic procedure in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fudan University School of Public Health (IRB 00002408 and FWA 00002399) under IRB #2021-09-0919. All respondents accessed the online questionnaire and read the informed consent. They clicked “agree” to the informed consent, which demonstrated they provided informed consent, and then filled out the questionnaire.

Results

Sociodemographics and HPV vaccination status among mothers and daughters

A total of 4044 parents were invited to participate in the questionnaire survey, of which 140 were completed by parents who had daughters outside 9–14, or were logically inconsistently or incorrectly completed (obviously inconsistent responses to logically related questions, e.g. extreme values of respondents’ age as parents of girls 9–14; or selection of all options to all questions, regardless of multiple or single choice questions). Thus, a total of 3904 parents were recruited in this study, with 74.43% being mothers and 25.57% being fathers. The mean age of the respondents was 42.76 ± 4.23, with 3113 (79.74%) aged ≤ 45 and 791 (20.26%) aged > 45. The majority of respondents had less than a bachelor’s degree (53.02%) and a single child (64.62%), and a plurality had a monthly family income ≤ 20000 CNY (43.42%). Parental gender, parental age, parental educational background, monthly household income, and number of children significantly differed across daughters’ HPV vaccination status (each p < .001) ().

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents.

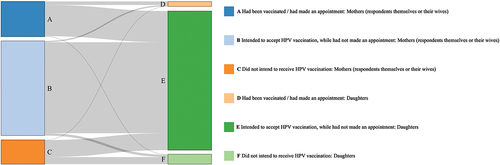

Of the respondents or their wives, 22.44% had received HPV vaccine or had made an appointment; furthermore, up to 84.13% were willing to accept HPV vaccine for themselves or their wives, regardless of their actual HPV vaccination status. In contrast, only 3.25% of respondents’ daughters had received HPV vaccine or had made an appointment, while 93.60% of respondents were willing to have their daughters vaccinated, regardless of their daughters’ actual HPV vaccination status. It showed poor consistency between HPV vaccine uptake and intent for themselves (or their wives) and that for their daughters (kappa value, 0.21; ).

Figure 1. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination status among mothers (respondents themselves or their wives) and daughters. “Had been vaccinated/had made an appointment” indicated the HPV vaccine uptake. “Intended to accept HPV vaccination, while had not made an appointment” indicated the intent to accept HPV vaccine; the intent was expressed by the respondents for themselves (or their wives) and for their daughters. “Did not intend to receive HPV vaccination” indicated no intent.

Parental WTP HPV vaccine for mothers (respondents themselves or their wives) and for daughters

We determined the parental WTP HPV vaccine by offering a range of payments. It was significantly associated with their vaccination status for themselves or their wives (p < .001) as well as for their daughters (p < .001), regardless of the types of HPV vaccine (). Additionally, parental WTP differed by types of HPV vaccine in mothers (p < .001) and in daughters (p < .001). Notably, the percentage of parental WTP ≤ 1000 CNY for themselves or their wives was determined to be the highest, regardless of the type of HPV vaccine (). Furthermore, the percentage of parental WTP ≥ 2001 CNY apparently increased along with the valency of HPV vaccine (from 2vHPV to 4vHPV, and then to 9vHPV) for themselves or their wives, whereas the percentage of parental WTP ≤ 1000 CNY decreased (). In contrast, the percentage of parental WTP ≤ 1000 CNY, 1001–2000 CNY, and ≥ 2001 CNY was highest (and considerably higher than other WTPs) for 2vHPV, 4vHPV, and 9vHPV, respectively, for their daughters ().

Table 2. Parental willingness to pay (WTP) human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for themselves (or their wives) across mothers’ HPV vaccine uptake and intent.

Table 3. Parental willingness to pay (WTP) human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for their daughters across daughters’ HPV vaccine uptake and intent.

Moreover, we compared the WTP (range of payment) for themselves (or their wives) and that for their daughters, stratified by types of HPV vaccine. It showed moderate to low consistency between the WTP for themselves (or their wives) and that for their daughters toward 2vHPV (kappa value, 0.54), 4vHPV (kappa value, 0.46), and 9vHPV (kappa value, 0.48) (). Notably, for 9vHPV, 65.37% of respondents were willing to pay ≥ 2001 CNY for their daughters, whereas 37.68% for themselves or their wives. Similarly, for 2vHPV, 68.62% of respondents were also willing to pay ≤ 1000 CNY for their daughters, while 49.61% for themselves or their wives.

Table 4. Consistency between parental willingness to pay (WTP) human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for themselves (or their wives) and their daughters by types of HPV vaccine.

We also estimated a point value of the WTP HPV vaccine using CVM. In total, the respondents showed higher WTP for their daughters (median, 2000 CNY/277 USD; IQR, 1000–3600 CNY/138–498 USD) than for themselves (median, 2000 CNY/277 USD; IQR, 1000–3500 CNY/138–483 USD) or their wives (median, 2000 CNY/277 USD; IQR, 800–3000 CNY/110–414 USD) (each p < .05). Parental WTP was compared in the two government subsidy scenarios, stratified by types of HPV vaccine (international vs domestic, 2vHPV vs 4vHPV and 9vHPV). The WTP was significantly higher for international HPV vaccine and 9vHPV (each p < .05), regardless of subsidy scenario, and mothers responded for themselves, or fathers responded for their wives ().

Table 5. Median value of willingness to pay (WTP) for parental preference of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines for themselves (or their wives) and their daughters in the two subsidy scenarios.

Parental preference for HPV vaccine in the two subsidy scenarios

We determined the parental preference for HPV vaccine and then compared the preference for themselves (or their wives) and that for daughters. In the two subsidy scenarios, the respondents moderately changed their preferred types of HPV vaccine. International 9vHPV, assumed domestic 9vHPV and domestic 2vHPV were most commonly preferred for parents themselves (or their wives) and for daughters (each >20%, except international 9vHPV for parents themselves or their wives) (). Furthermore, in subsidy scenario 2 (international 2vHPV is freely provided; parents need to pay the difference in prices when they choose other HPV vaccines), 9vHPV was more preferred for parents themselves (or their wives) or their daughters, compared with that in subsidy scenario 1 (domestic 2vHPV is freely provided; parents need to pay full price when they choose other HPV vaccines) (). Remarkably, between the two scenarios, preference for international 9vHPV (from 23.98% to 24.44% with an increase of 0.46%) and assumed 9vHPV (from 23.92% to 24.23% with an increase of 0.31%) remained consistently high for daughters; in contrast, preference for international 9vHPV (from 17.47% to 18.29% with an increase of 0.82%) and assumed 9vHPV (from 22.23% to 23.28% with an increase of 1.05%) showed a higher increase for parents themselves (or their wives).

Table 6. Parental preference for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for themselves (or their wives) and their daughters in two government subsidy scenarios.

Respondents’ preference for HPV vaccine varied across sociodemographic groups (). In the two subsidy scenarios, the respondents commonly preferred domestic HPV vaccines. Moreover, those who were mothers, ≤45 years, had a higher educational level or higher monthly household income were likely to prefer higher valency HPV vaccines for themselves (or their wives) as well as their daughters. Similarly, respondents who had been vaccinated or had made an appointment strongly preferred higher valency HPV vaccines, while those who did not intend to receive vaccination preferred 2vHPV.

Table 7. Parental preference for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for themselves or their wives by using stratified discrete choice experiment (DCE).

Table 8. Parental preference for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for their daughters by using stratified discrete choice experiment (DCE).

Discussion

This study found that HPV vaccine uptake among girls aged 9–14 in Shanghai, a socioeconomically developed metropolis in China, remained low. In contrast, parental intent to vaccinate these girls was high, regardless of HPV vaccination status among parents themselves (or their wives). HPV vaccine uptake remains very low in girls aged 9–14 in China, approximately 2.2% nationwide.Citation12,Citation24 Multiple factors influencing the HPV vaccine decision-making, among which parental WTP HPV vaccine for their daughters remains crucial. In our study, parental WTP for their daughters increased along with the valency of HPV vaccine, compared with low WTP for themselves (or their wives) across diverse types of HPV vaccine. Parents were likely to pay more for their children for HPV vaccine and COVID-19 vaccine.Citation25,Citation26 This finding underscored the importance of considering the valency in preparing HPV vaccination strategy and indicated the potential impact of policy interventions on diverse types of vaccines. Currently, multiple regions have launched the pilot programs of HPV immunization in China, among which domestic 2vHPV is freely provided. Given the financial sustainability, 9vHPV might not be freely provided in these programs in near future. However, local policy makers could leverage parental WTP and improve vaccination coverage among the target population (such as girls aged 9–14), by ensuring the supply of higher valency HPV vaccines as a supplement to the above programs. Thus, it may be crucial to start with parents to promote HPV vaccine for girls, as described elsewhere.Citation27,Citation28

In this study, the mean value of parental WTP HPV vaccine were 2077 CNY/287 USD for themselves (or their wives) and 2169 CNY/299 USD for their daughters, covering three doses of international or domestic 2vHPV in China. These findings aligned with previous studies, such as a study in Thailand indicating that one-third of mothers would copay less than 17 USD for 2vHPV.Citation29 So far, HPV vaccine has not been included in the national immunization program in China, leaving most females aged 9–45 unvaccinated or delaying vaccination due to HPV vaccine cost.Citation30 In China, three payment mechanisms currently exist for HPV vaccine, including self-payment for vaccination (mainly for adult women), free vaccination for targeted populations (such as providing domestic 2vHPV for girls in grade 1 of middle schools), and co-payment between local governments and individuals (such as providing international or multivalent HPV for girls in grade 1 of middle schools), with the first remaining common in most regions.Citation31,Citation32 Additionally, two-dose schedule has been gradually approved for all HPV vaccines in China since 2023. In our study, the three-dose schedule was mainly considered; in contrast, reduced dosing schedule may reduce the vaccination cost and increase the coverage.Citation33 Thus, a multifaceted approach combining government subsidies, free vaccination programs, and co-payment mechanisms could improve HPV vaccine affordability and coverage, particularly among girls aged 9–14, in socioeconomically developed areas and potentially nationwide.

Furthermore, our study revealed that the government subsidy mechanism for HPV vaccination may impact parental preference for themselves (or their wives) and their daughters. In scenario 2 (pay the difference in prices), more parents preferred 9vHPV, regardless of domestic and international manufacturers, compared with that in scenario 1 (pay full price). In scenario 2, parents also had higher WTP 9vHPV for their daughters than for themselves. However, the percentage of parents preferring international 9vHPV for their daughters remained stable, followed by those preferring assumed domestic 9vHPV for daughters. It suggested that parents preferring 9vHPV for daughters were less likely to be affected by the vaccination cost, compared with their preference for themselves or their wives. Previous studies have documented that females who preferred 4vHPV or 9vHPV were willing to pay more to receive these multivalent HPV vaccines in Fujian, China, and Thailand.Citation26,Citation34 Similarly, higher parental acceptance was observed for self-paid meningitis and encephalitis-related vaccines and influenza vaccines than for free vaccines in China.Citation35,Citation36 Therefore, further study is necessary to assess the impact of other factors on vaccine decisions in addition to payment. For example, parental history of HPV infection and knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccine played significant roles.Citation37 Recently, China has continued to promote pilot programs of HPV immunization within the “Health City Project” to increase the HPV vaccine uptake among girls, raising concerns about financial sustainability. Our findings provide preliminary evidence for improving subsidy strategy in the HPV vaccination for girls, which could specifically increase HPV vaccine uptake among diverse female populations.

This study further determined the parental preferences for themselves (or their wives) and for their daughters across sociodemographic groups. These preferences were associated with educational level and household income, as described elsewhere.Citation36,Citation38 Similarly, sufficient knowledge and a positive attitude are correlated with HPV vaccination uptake; however, higher income might not always lead to greater WTP.Citation39–41 In our study, we found that parents had similar preferences for themselves (or their wives) and for their daughters, which may contribute to the establishment of concurrent HPV vaccination for daughters and mothers, though parental WTP differed between them. Recent reports indicate that girls and their mothers can make appointments for the HPV vaccine at the same time in Hunan, China.Citation42 Remarkably, parents commonly preferred domestic HPV vaccines for themselves (or their wives) and for their daughters in our study, a departure from previous findings.Citation43 This trend is likely influenced by lower vaccine prices by domestic manufacturers in the subsidy scenarios, in combination with increasing health promotion campaigns. Thus, our findings indicated that the valency of HPV vaccine, vaccine manufacturer, and payment might interact in HPV vaccine decision-making. It would facilitate designing and prompting HPV immunization programs in China, catering to diverse female populations.

Our study has research strengths. First, we systematically characterized the parental WTP HPV vaccine and preference for themselves (or their wives) and their daughters in Shanghai, China. Second, we assumed a domestically produced 9-valent HPV vaccine, as multiple HPV vaccines of domestic manufacturers are in clinical trials in China. It would allow our findings to effectively inform potential HPV vaccine strategy shortly. Third, our study may provide evidence by analyzing parental WTP HPV vaccine for their daughters and comparing the difference between the two subsidy scenarios for better optimizing HPV immunization programs to meet local needs.

This study also has limitations. First, this study was only conducted in Shanghai, so the generalizability might only apply to local HPV immunization programs. Also, it might apply to socioeconomically developed areas in China, where they were more likely to support and/or establish the programs of HPV immunization. Second, the online questionnaire and convenience sampling strategy may result in selection bias in the study population, as accurate estimation of response rates or characterization of non-responders could have been more feasible, which also resulted in the generalizability. To reduce potential bias, we implemented quality control measures during data collection to enhance the randomness and representativeness of the participants. Third, it was noted that not all respondents were mothers; a small proportion of respondents were fathers, who might underestimate the willingness of their wives to be vaccinated. Additionally, the monetary valuation of WTP was determined based on the current prices and local program of HPV immunization, which might change over the years along with economic fluctuations.

Our study found low uptake of the HPV vaccine in girls aged 9–14 in Shanghai, China, with high parental intent to accept HPV vaccine for those girls. Moreover, parental WTP for daughters increased along with the valency of HPV vaccine, while the WTP for parents themselves (or their wives) was commonly lower. In the two government subsidy scenarios, the percentage of parents preferring 9vHPV for daughters was consistently high, suggesting the valency of HPV vaccine is very influential in vaccine preference, in addition to vaccine price. The findings determined the factors impacting HPV vaccine decision-making in a socioeconomically developed setting, highlighting potential areas for further policy intervention. Thus, our study would provide substantial evidence for designing and implementing of HPV immunization programs for girls aged 9–14 in socioeconomically developed regions in China.

Author contribution

YL and XG conceived of this study. YL, XG, and XL designed the questionnaire. XL, JL, QZ, and WZ prepared the online questionnaire and investigation. WZ, YL, and XF analyzed data and drafted initial manuscript. YL, XG, JL, QZ, and XS critically revised the manuscript and helped interpret data. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate all parents completing the online questionnaire. We also thank Dr. Abram L. Wagner for editing and proofreading the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

YL received the grant from MSD China for research in modeling and health economics of HPV vaccination in adolescent girls, and also kinetics of immune response to COVID-19 infection after recovery.

Data availability statement

The dataset analyzed during the current study is not publicly available due to the privacy restriction by IRB approval, but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zhang W XX, W SY, Zhang ZN, Yu WZ, Yu WZ. Expert recommendations on human papillomavirus vaccine immunization strategies in China. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. [2022 Sep 6]. 56(9):1165–10. Chinese. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20220505-00443.

- Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, Unger ER, Romero JR, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. [2019 Aug 16]. 68(32):698–702. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a3.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV Vaccine Safety. 2021 [accessed 2023 Oct 10]. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/vaccine-safety-data.html;.

- Villa A, Patton LL, Giuliano AR, Estrich CG, Pahlke SC, O’Brien KK, Lipman RD, Araujo MWB. Summary of the evidence on the safety, efficacy, and effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccines: umbrella review of systematic reviews. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020 Apr. 151(4):245–54.e24. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2019.10.010.

- Pan X, Lv H, Chen F, Wang Y, Liang H, Shen L, Chen Y, Hu Y. Analysis of adverse events following immunization in Zhejiang, China, 2019: a retrospective cross-sectional study based on the passive surveillance system. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(10):3823–30. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1939621.

- Zhu FC, Hu SY, Hong Y, Hu YM, Zhang X, Zhang YJ, Pan Q-J, Zhang W-H, Zhao F-H, Zhang C-F, et al. Efficacy, immunogenicity and safety of the AS04-HPV-16/18 vaccine in Chinese women aged 18-25 years: end-of-study results from a phase II/III, randomised, controlled trial. Cancer Med. 2019;8(14):6195–211. doi:10.1002/cam4.2399.

- Saldanha C, Vieira-Baptista P, Costa M, Silva AR, Picão M, Sousa C. Impact of a high coverage vaccination rate on human papillomavirus infection prevalence in young women: a cross-sectional study. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020;24(4):363–6. Epub 2020/08/17. doi: 10.1097/lgt.0000000000000564.

- Marcellusi A, Mennini FS, Sciattella P, Favato G. Human papillomavirus in Italy: retrospective cohort analysis and preliminary vaccination effect from real-world data. Eur J Health Econ. 2021;22(9):1371–9. Epub 2021/06/13. doi: 10.1007/s10198-021-01317-w. PubMed PMID: 34117988; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8558199.

- Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, Wang J, Roth A, Fang F, Sundström K, Dillner J, Sparén P. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1340–8. Epub 2020/10/01. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1917338. PubMed PMID: 32997908.

- Tran PT, Riaz M, Chen Z, Truong CB, Diaby V. An umbrella review of the cost effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccines. Clin Drug Investig. 2022;42(5):377–90. Epub 2022/05/01. doi: 10.1007/s40261-022-01155-5. PubMed PMID: 35488964.

- National Medical Products Administration. 2019 Annual drug review report. 2019 [accessed 2023 Oct 10]. https://www.nmpa.gov.cn/xxgk/fgwj/gzwj/gzwjyp/20200731114330106.html;.

- Song Y, Liu X, Yin Z, Yu W, Cao L, Cao L, Ye J, Li L, Wu J. Human papillomavirus vaccine coverage among the 9-45-year-old female population of China in 2018–2020. Chin J Vaccines Immun. 2021;27(5):570–5.

- World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage. 2022 [accessed 2023 Oct 10]. https://immunizationdata.who.int/pages/coverage/hpv.html?CODE=JPN&ANTIGEN=15HPV1_F&YEAR;.

- Zhuang QY, Wong RX, Chen WM, Guo XX. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding human papillomavirus vaccination among young women attending a tertiary institution in Singapore. smedj. 2015;57(6):329–33. Epub 2016/06/30. doi:10.11622/smedj.2016108. PubMed PMID: 27353611; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4971453.

- Nakagawa S, Ueda Y, Yagi A, Ikeda S, Hiramatsu K, Kimura T. Corrected human papillomavirus vaccination rates for each birth fiscal year in Japan. Cancer Sci. 2020;111(6):2156–62. doi:10.1111/cas.14406.

- Suzuki Y, Sukegawa A, Ueda Y, Sekine M, Enomoto T, Melamed A, Wright JD, Miyagi E. The Effect of a web-based cervical cancer survivor’s story on parents’ behavior and willingness to consider human papillomavirus vaccination for daughters: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022;8(5):e34715. Epub 2022/04/15. doi: 10.2196/34715. PubMed PMID: 35421848; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9178460.

- Xie Y, Su LY, Wang F, Tang HY, Yang QG, Liu YJ. Awareness regarding and vaccines acceptability of human papillomavirus among parents of middle school students in Zunyi, Southwest China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(11):4406–11. Epub 2021/07/30. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1951931. PubMed PMID: 34324411; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8828083.

- Newman PA, Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Baiden P, Tepjan S, Rubincam C, Doukas N, Asey F. Parents’ uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines for their children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e019206. Epub 2018/04/22. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019206. PubMed PMID: 29678965; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5914890.

- Wong LP, Han L, Li H, Zhao J, Zhao Q, Zimet GD. Current issues facing the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccine in China and future prospects. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1533–40. Epub 2019/04/25. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1611157. PubMed PMID: 31017500; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6746483.

- Xie H, Zhu HY, Jiang NJ, Yin YN. Awareness of HPV and HPV vaccines, acceptance to vaccination and its influence factors among parents of adolescents 9 to 18 years of age in China: a cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2023;71:73–8. Epub 2023/04/08. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2023.03.007. PubMed PMID: 37028228.

- Zhang Z, Shi J, Zhang X, Guo X, Yu W. Willingness of parents of 9-to-18-year-old females in China to vaccinate their daughters with HPV vaccine. Vaccine. 2023;41(1):130–5. Epub 2022/11/22. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.11.016. PubMed PMID: 36411136.

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Proposal on strengthening popular science publicity and improving HPV vaccination. 2021 [Accessed 2023 Oct 10]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/tia/202112/af51b14c0ca04799b55b8322559751ac.shtml;.

- Mangham LJ, Hanson K, McPake B. How to do (or not to do) … Designing a discrete choice experiment for application in a low-income country. Health Policy And Planning. 2009;24(2):151–8. Epub 2008/12/30. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn047. PubMed PMID: 19112071.

- Wang Z, Wang J, Fang Y, Gross DL, Wong MCS, Wong ELY, Lau JTF. Parental acceptability of HPV vaccination for boys and girls aged 9–13 years in China – a population-based study. Vaccine. 2018;36(19):2657–65. Epub 2018/04/03. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.057. PubMed PMID: 29606519.

- Catma S, Reindl D. Parents’ willingness to pay for a COVID-19 vaccine for themselves and their children in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(9):2919–25. Epub 2021/05/01. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1919453. PubMed PMID: 33929290; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8428178.

- Liao CH, Liu JT, Pwu RF, You SL, Chow I, Tang CH. Valuation of the economic benefits of human papillomavirus vaccine in Taiwan. Value Health. 2009;12(Suppl 3):S74–7. Epub 2010/07/10. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00632.x. PubMed PMID: 20586987.

- Smith LE, Amlôt R, Weinman J, Yiend J, Rubin GJ. A systematic review of factors affecting vaccine uptake in young children. Vaccine. 2017;35(45):6059–69. Epub 2017/10/05. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.046. PubMed PMID: 28974409.

- Huang Z, Wagner AL, Lin M, Sun X, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Boulton ML, Ren J, Prosser LA. Preferences for vaccination program attributes among parents of young infants in Shanghai, China. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2020;16(8):1905–10. Epub 2020/01/25. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1712937. PubMed PMID: 31977272; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7482902.

- Kruiroongroj S, Chaikledkaew U, Thavorncharoensap M. Knowledge, acceptance, and willingness to pay for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among female parents in Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(13):5469–74. Epub 2014/07/22. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.13.5469. PubMed PMID: 25041020.

- Hou ZY, Chang J, Yue DH, Fang H, Meng QY, Zhang YT. Determinants of willingness to pay for self-paid vaccines in China. Vaccine. 2014;32(35):4471–7. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.047. PubMed PMID: WOS:000340141200016.

- People’s government of Guangdong Province. provide free bivalent HPV vaccine for school-age girls starting this month in Guangdong [accessed 2023 Sep 3]. https://www.gd.gov.cn/gdywdt/bmdt/content/post_4011995.html

- Sichuan provincial department of education. universalize HPV vaccination for 13–14 year old school girls. 2021 [accessed 2023 Oct 10]. http://edu.sc.gov.cn/scedu/c100494/2021/11/19/19b304d4d875457ea3151069a3cdc5b8.shtml;.

- Kreimer AR, Cernuschi T, Rees H, Brotherton JML, Porras C, Schiller J. Public health opportunities resulting from sufficient HPV vaccine supply and a single-dose vaccination schedule. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2023;115(3):246–9. doi:10.1093/jnci/djac189.

- Lin Y, Lin Z, He F, Chen H, Lin X, Zimet GD, Alias H, He S, Hu Z, Wong LP, et al. HPV vaccination intent and willingness to pay for 2-,4-, and 9-valent HPV vaccines: a study of adult women aged 27–45 years in China. Vaccine. 2020;38(14):3021–30. Epub 2020/03/05. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.02.042. PubMed PMID: 32127227.

- Maimaiti H, Lu J, Guo X, Zhou L, Hu L, Lu Y. Vaccine uptake to prevent meningitis and encephalitis in Shanghai, China. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(12). Epub 2022/12/24. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10122054. PubMed PMID: 36560463; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9787460.

- Lu X, Lu J, Zhang L, Mei K, Guan B, Lu Y. Gap between willingness and behavior in the vaccination against influenza, pneumonia, and herpes zoster among Chinese aged 50-69 years. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021;20(9):1147–52. Epub 2021/07/22. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2021.1954910. PubMed PMID: 34287096.

- Grabiel M, Reutzel TJ, Wang S, Rubin R, Leung V, Ordonez A, Wong M, Jordan E. HPV and HPV vaccines: the knowledge levels, opinions, and behavior of parents. J Community Health. 2013;38(6):1015–21. Epub 2013/07/13. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9725-6. PubMed PMID: 23846387.

- Zhu S, Chang J, Hayat K, Li P, Ji W, Fang Y. Parental preferences for HPV vaccination in junior middle school girls in China: a discrete choice experiment. Vaccine. 2020;38(52):8310–7. Epub 2020/11/24. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.11.020. PubMed PMID: 33223307.

- Aragaw GM, Anteneh TA, Abiy SA, Bewota MA, Aynalem GL. Parents’ willingness to vaccinate their daughters with human papillomavirus vaccine and associated factors in Debretabor town, Northwest Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(1):2176082. Epub 2023/02/17. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2023.2176082. PubMed PMID: 36794293; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC10026865.

- Barnack JL, Reddy DM, Swain C. Predictors of parents’ willingness to vaccinate for human papillomavirus and physicians’ intentions to recommend the vaccine. Women's Health Issues. 2010;20(1):28–34. Epub 2010/02/04. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.08.007. PubMed PMID: 20123174.

- Wong CKH, Man KKC, Ip P, Kwan M, McGhee SM. Mothers’ preferences and willingness to pay for human papillomavirus vaccination for their daughters: a discrete choice experiment in Hong Kong. Value in Health. 2018;21(5):622–9. Epub 2018/05/14. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.10.012. PubMed PMID: 29753361.

- Hunan Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 9-valent HPV vaccine to expand the population aged 9–45: Hunan provincial center for disease control and prevention outpatient clinic “first shot” start. 2022 [accessed 2023 Oct 10]. http://www.hncdc.com/ms//html/web/news/zhongxindongtai/5424.html;.

- Zhou L, Gu B, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng P, Huo Y, Liu G, Zhang X. On imported and domestic human papillomavirus vaccines: cognition, attitude, and willingness to pay in Chinese medical students. Front Public Health. 2022;10:863748. Epub 2022/06/02. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.863748. PubMed PMID: 35646758; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9133910.