ABSTRACT

Vaccination is one of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century, with a tremendous impact in the prevention and control of diseases. However, the recent reemergence of vaccine-preventable diseases calls for a need to evaluate current vaccination practices and disparities in vaccination between high-income countries and low-and-middle-income countries. There are massive deficits in vaccine availability and coverage in resource-constrained settings. Therefore, this perspective seeks to highlight the reemergence of vaccine-preventable diseases in Africa within the lens of health equity and offer recommendations on how the continent should be prepared to deal with the myriad of its health systems challenges. Among the notable factors contributing to the reemergence, stand health inequities affecting vaccine availability and the dynamic vaccine hesitancy. Strengthening health systems and addressing health inequities could prove useful in halting the reemergence of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Introduction

The discovery of effective and safe vaccines against several infectious diseases has revolutionized the practice of modern medicine. Before vaccines, infectious diseases were major threats to human health and critical factors in reducing life expectancy, increasing morbidity and cost of healthcare services.Citation1 Vaccination, along with sanitation and clean drinking water, are public health interventions that are undeniably responsible for improved health outcomes globally.Citation2 It is estimated that over 4 million deaths globally, are averted annually as a result of vaccination. In addition to offering protection from diseases, immunization also brings children and families into contact with health systems, providing an avenue for the delivery of other basic health services such as nutritional support and growth monitoring, health education and family planning and postpartum care, thereby helping to reduce maternal and childhood morbidity and mortality.Citation3–8

Since the establishment of the World Health Organization (WHO) Expanded Program of Immunization (EPI) in 1974 and the Global Alliance for Vaccine and Immunisation (GAVI) in 2000, global coverage of vaccination against many important infectious childhood diseases has been enhanced dramatically.Citation2,Citation9 This has led to eradication and control of major vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs) such as polio and measles in many regions of the world. Despite the major gains achieved in the fight against infectious diseases of epidemic potential as a result of vaccination, various health disparities exist across regions.Citation10 Access to affordable, timely and new vaccines still remains a huge challenge among the poorest and most vulnerable populations in the community.Citation9 This has led to persistence of these VPDs in these communities due to limited coverage of immunization.

The African continent still lacks vaccine manufacturing capacity, despite the life-saving intervention being more than a century old.Citation10 This is the case despite the continent bearing the highest mortality caused by infectious diseases.Citation11 Less than 1% of the vaccines needed in Africa are manufactured within the continent. These health disparities came to a clearer light during the COVID-19 pandemic when access to the COVID-19 vaccine was a huge challenge within the continent.Citation5 The problem of limited vaccines is further compounded by limited access to other drugs for treating infectious diseases and underdeveloped primary healthcare systems to recognize and timely treat diseases of epidemic potential.Citation12

While the major gains against infectious diseases owing to vaccination are largely celebrated worldwide, contemporary times are proving that there could be a reversal in the status quo. The incidence of VPDs has been rising in recent years, even in high-income countries with universal access to vaccines.Citation13 Since 2008, the Global Health Program at the Council on Foreign Relations has tracked global outbreaks of measles, mumps, polio, rubella, pertussis, diphtheria, varicella, meningitis and rotavirus. Worse still, some of the VPDs such as measles have not yet been eradicated at a global level and continue to cause outbreaks in many parts of the world.Citation14 Recently, cases of polio, which was initially eradicated, have also been reported in other parts of the world, including Africa and Asia.

The reemergence of these VPDs amidst rising new emerging infectious diseases and global pandemics threatens to reverse the initial gains made in the fight against infectious diseases. This is further compounded by the emergence of multi-drug resistant pathogens. Amidst all these challenges, it has become more logical for countries and regions to invest in strengthening their healthcare systems and empower the people to be vigilant in taking care of their health status. In this perspective, therefore, we highlight the reemergence of VPDs in Africa within the lens of health equity and offer recommendations on how the continent should be prepared to deal with the myriad of its health system challenges.

Overview of VPDs and impact of vaccination; historical perspective

The WHO VPDs have a range of diseases that can be prevented and controlled by vaccination.Citation15 Even though the list is inexhaustible, the most common VPDs in the African region include: cholera, Ebola Virus disease, hepatitis, Human Papillomavirus (HPV), influenza, malaria, tetanus, measles, rubella, meningococcal meningitis, pneumonia, polio, rotavirus, typhoid and yellow fever. Since the launch of the EPI in 1974, vaccination in Africa has increased substantially, leading to major gains in infectious disease control.Citation16 In the WHO African region, vaccination coverage against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis, increased from 57% in 2000 to 74% in 2016.Citation17 Furthermore, a significant reduction in measles-related deaths was noted between 2000 and 2015.Citation18,Citation19 Evidence shows that measles vaccination led to 84% reduction in measles-related deaths among the affected population.Citation18,Citation20,Citation21

The trends were similar for majority of diseases including polio, rubella, diphtheria, and hepatitis. For instance, the introduction of polio vaccine led to a substantial decline in the number of reported cases from 350,000 cases in 1958 to only 6 cases in 2021.Citation22 Similarly, since the WHO recommended the introduction of hepatitis B vaccine into the EPI in 1991, there has been a worldwide drop in sero-prevalence of Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), an indicator of chronic hepatitis B infection. The HBsAg prevalence has dropped from 4.7% in the pre-vaccination era (1980s to early 2000s) to 1.3% in 2015.Citation23

Overall, the substantial gains achieved during optimal immunization coverage just clearly indicate the major gains achieved across the continent as a result of vaccination. Vaccination led to significant reduction in morbidity and mortality associated with vaccine-preventable diseases.

Current epidemiology of VPDs and re-emergence

Globally, 4 million deaths are averted every year by childhood vaccination.Citation24 There is potential for 50 million deaths to be prevented through immunization between 2021 and 2030. In 2018, 700,000 children died due to VPDs, of which low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) were disproportionately highly affected as compared to high-income countries.Citation25 The WHO’s essential program on immunization for 2023 lists 23 VPDs. However, this paper only reports the current epidemiology of measles, polio, rubella, hepatitis B and diphtheria, which are of epidemic potential.Citation26

Measles remains one of the major leading causes of death globally, with the highest number of cases reported in the WHO African region.Citation20 Although measles vaccination has contributed to substantial reduction in averting measles-related deaths, major reverse in trends is currently being experienced across the continent. Recent reports indicate that from 2017 to 2019, annual incidence of measles increased from 69.2 cases/million population to 559.8 cases/million population, then dropping to 81.9 cases/million population in 2021.Citation27 Deaths from measles increased from 61,166 deaths in 2017 to 104,543 in 2019 then dropping to 66,230 in 2021.Citation27 This threatens the gains made previously in tackling the disease.

Similarly, despite many countries triumphing in eradication of polio, cases have been recently reported in some countries in Africa such as Malawi. From 2022 to 2023 Malawi has recorded five cases of polio.Citation28 Surveillance of data on rubella is scanty because most countries do not have robust surveillance systems for the disease.Citation29 In the period between 2007 and 2016, a total of 242 cases of congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) were reported to the WHO from the Africa region.Citation29 The small numbers are not necessarily from effects of vaccines but insufficient reporting, which is compounded by lack of targets for elimination of rubella.Citation29

With regard to hepatitis B virus disease, globally, in 2019 about 296 million people were living with chronic hepatitis, with an estimated yearly incidence of around 1.5 million cases and there were 820,000 deaths from the disease.Citation23 Africa had the second highest number of people with chronic hepatitis which was estimated to be 81 million people, representing 6.1% of the population. Since the WHO recommended the introduction of hepatitis B vaccine into the EPI in 1991, there has been a worldwide drop in sero-prevalence of Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), an indicator of chronic hepatitis B infection. The HBsAg prevalence has dropped from 4.7% in the pre-vaccination era (1980s to early 2000s) to 1.3% in 2015.Citation23 Despite this drop in the global prevalence of HBsAg, Africa still retains a higher prevalence of 6.1%.Citation30 This shows the need for escalating efforts toward hepatitis B vaccination in Africa.

For diphtheria, about 10,000 cases were recorded worldwide in 2022.Citation31 In the wake of a 3-fold increase in the national vaccination programs for diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus, the proportion of diphtheria cases in children <15 years has been decreasing.Citation31 Despite the reported decrease in cases of diphtheria, data on the disease are still scanty, with data from the WHO being 81% complete.Citation30 In Africa, the most recent outbreak of diphtheria was reported in Nigeria (in early 2023) which recorded 557 cases affecting 21 of their 36 states.Citation32 Vaccination coverage gaps have been a substantial problem in Nigeria. Insufficient vaccination of children renders significant segments of the population vulnerable to diphtheria. According to the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), the epidemic was notably intense in regions with lower vaccination rates.Citation33 Other possible reasons for this outbreak include the disruption of health services caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, political instability, and economic challenges, which result in missed vaccinations and decreased public health interventions.Citation33

Overall, vaccines have contributed to a decrease in the incidence and prevalence of VPDs and their associated mortality and morbidity. This is as a result of the inclusion of vaccinations in standard care guidelines, resulting in recorded low levels of VPD occurrences.Citation34 However, there is notable suboptimal surveillance for most VPDs and vaccine refusal among communities, which poses a risk for VPDs resurgence and persistence and undermines efforts to set and achieve realistic elimination goals for the diseases.Citation35

Factors that contribute to reemergence and resurgence of VPDs

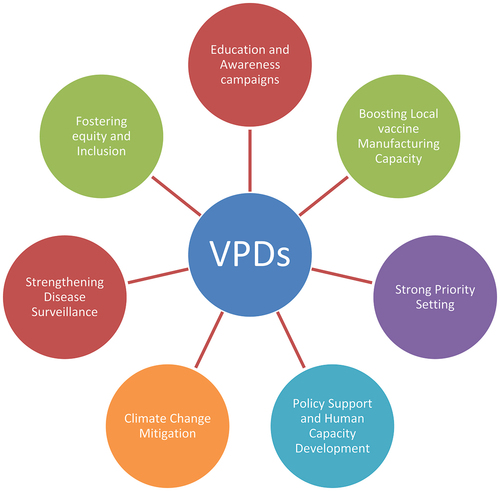

There are various factors contributing to the reemergence and resurgence of VPDs in Africa as summarized by .

Figure 1. Schematic representation of factors that contribute to reemergence and resurgence of VPDs in Africa.

Africa is witnessing reemergence of outbreaks of VPDs over the past years. Contrary to the popular belief that the resurgence of VPDs is totally due to laxity in vaccination, factors leading to the reemergence of VPDs remain multi-factorial and multiplex.Citation36 In this section, we highlight some common factors leading to the resurgence of VPDs.

The overall contributing factor to the reemergence of VPD is a decline in the vaccination coverage. This is due to vaccine hesitancy, lack of access to vaccines, missed opportunity to vaccinate, gaps in healthcare infrastructure and increasing pressure on the healthcare system.Citation12 Since 2019, there has been a notable decrease in vaccine uptake and an increase in the incidence of VPDs. This could be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic which exerted a lot of pressure on already weak healthcare systems, disrupting routine healthcare programs including immunization.Citation37–39 For instance, measles vaccination at 1 year of age in the WHO African region decreased from 70% in 2018 to 68% in 2021. Almost 17,500 cases of measles were recorded in the African region between January and March 2022, marking a 400% increase compared with the same period in 2021.Citation15 Twenty African countries reported measles outbreaks in the first quarter of 2022, eight more than those in the first 3 months of 2021.Citation40

Low vaccine coverage could also be attributed to missed opportunities for vaccination, either due to a faulty healthcare system or the inability of parents to recognize the importance of vaccination, including limited knowledge of the current vaccination schedule.Citation41 Among children, pooled African regional prevalence of Missed Opportunities for Vaccination (MOV) was found to be 27.3% from a systematic review, about 47.0% from secondary analyses of Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data, and 62.1% according to a study using DHS and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) data.Citation42 When a significant portion of the population is not vaccinated, it creates opportunities for diseases to spread.Citation43 Reduction in vaccine coverage results in a decline in herd immunity perpetuating the reemergence of outbreaks.Citation44 For instance, in the early 2000s, declining vaccine coverage in some European countries led to decreased herd immunity against pertussis (whooping cough). This resulted in several pertussis outbreaks.Citation45

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), there is a growing recognition of outdated immunization supply chain systems.Citation46,Citation47 These systems, which were designed in the late 1970s to manage fewer, less expensive and less bulky vaccines, are being confronted with several new realities.Citation48 Among these are the needs to handle a widening variety of new vaccines and immunization schedules, a greater diversity of service delivery strategies, an ever-expanding target population to vaccinate, and an increased cold chain infrastructure requirement.Citation48 Taken together, these factors have created significant storage and transport shortfalls at all levels, which ultimately hinder progress toward coverage and equity goals in the continent, hence contributing to the resurgence and reemergence of VPDs.

Furthermore, clear evidence exists that vaccines supply in the African region is greatly affected by weak priority setting, ineptitude by decisionmakers, and lack of expert involvement in making decisions on vaccine procurement, storage and distribution.Citation38,Citation49 Africa is home to 20% of the global burden of infectious diseases, yet healthcare systems are inefficient and fragile.Citation50 The healthcare systems are largely underfunded, affecting procurement of essential drugs and vaccines. The inefficiencies in domestic healthcare financing greatly contribute to Africa continent’s poor primary health outcomes such as limited access to timely, affordable and quality health preventive and curative services.Citation51 In times of pandemics, these health disparities are largely exposed. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was evidently shown that government struggled setting balanced priorities amidst constrained resources. For instance, a situational analysis in Nigeria revealed that even though most vaccines were available during the pandemic, weak vaccine procurement strategies, limited evidence on strategies for prioritizing recipients and approaches for rolling out mass vaccination programs for the entire population, lack of a communication strategy to reduce the incidence of vaccine hesitancy and failures to proactively address vaccine hesitancy through the implementation of vaccination programs, were the key issues that impeded timely access to vaccines.Citation38 The pandemic further exposed the lack of capacity and ineptitude by decisionmakers on the considerations required to be made prior to procurement and use of vaccines.Citation38

Another factor contributing to the reemergence of VPDs is global travel and internal migration. The re-introduction of diseases via international travel is a public health concern. In Ghana, Jirapa district experienced a mixed outbreak of streptococcal and meningococcal meningitis in early 2016, facilitated by migration.Citation52 Many travelers are not adequately vaccinated before travel. As a result, infected travelers end up re-introducing VPDs when returning to areas with susceptible populations. The international spread of poliomyelitis, Neisseria meningitidis serogroup W135 meningococcal infections, measles, and influenza provide strong evidence of the role of international travel in the globalization of VPDs.Citation53

Lack of local vaccine production in Africa cannot go unnoticed in the African continent when it comes to the reemergence of VPDs in the continent. This challenge has been exacerbated by various factors, including the reliance on vaccine imports, limited local manufacturing capacity, and the associated delays in vaccine availability and distribution. The inability to manufacture vaccines locally has hindered timely and equitable access to vaccines, leading to gaps in immunization coverage and leaving populations vulnerable to VPDs.Citation54 The lack of local vaccine manufacturing capacity has also contributed to challenges in responding to emerging infectious diseases and outbreaks, as highlighted by the delayed and limited access to vaccines during public health emergencies. This has been particularly concerning in the context of diseases such as Ebola, measles, and polio, where interruptions in vaccination programs and the inability to rapidly deploy vaccines, have increased the risk of VPDs resurgence.Citation51,Citation55

Furthermore, breakdowns in healthcare systems during conflicts, civil unrest and natural disasters disrupt healthcare systems, including vaccination programs. For instance, in 2019, large outbreaks of measles were reported in the Demographic Republic of Congo.Citation56,Citation57 The majority of these cases were reported in health zones that were largely impacted by civil unrest and experienced multiple disruptions of essential service delivery, including immunization.Citation56–58 Sixty-three percent of these cases were unvaccinated or their vaccination status could not be determined, reflecting suboptimal immunization among the general population.Citation59 Even though conflicts and civil unrests are common in some parts of Africa, there are limited data on the effects of political unrest on vaccination programs in Africa.Citation60

Regarding climate change, Africa has experienced a number of landslides and floods which disrupted routine immunization programs in countries such as Malawi and Mozambique.Citation61 In Malawi, tropical cyclones disrupted roads and health facilities, led to displacements of thousands of individuals and greatly impacted routine immunization programs.Citation61 Clear evidence also exist that climate change remains one of the key drivers of the dynamics of many infectious diseases, including those that are vaccine-preventable. Enteric diseases such as cholera are greatly precipitated by flooding events. This was seen in Malawi between 2022 and 2023, when there was a huge resurgence of cholera cases in the aftermath of tropical cyclone stormsCitation2,Citation61,Citation62

Lastly, reemergence of VPDS can also be attributed to vaccine-derived strains. All cases reported in Africa concerning the reemergence of polio were traced back to the vaccine administered.Citation63,Citation64

In conclusion, VPDs reemergence is multifactorial in nature, with the low vaccination coverage being the best predictor of recurrence of an eliminated VPD outbreak.

Vaccine and VPDs in Africa: a health equity challenge

According to the WHO, health equity is defined as “the absence of unfair, avoidable, or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically, or by other dimensions of inequalities such as sex, gender, ethnicity, disability, or sexual orientation.”Citation65 Health equity is achieved when everyone can attain their full potential for health and well-being. Health and health equity are determined by the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, play and age, as well as biological determinants. Structural determinants (political, legal, and economic) with social norms and institutional processes shape the distribution of power and resources determined by the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, play and age.Citation65

People’s living conditions, access to timely, affordable and quality healthcare are determined by the social, cultural, and political determinants of health and is usually made worse by discrimination, stereotyping, and prejudice based on sex, gender, age, race, ethnicity, or disability, among other factors.Citation66–68 Discriminatory practices are often embedded in institutional and systems processes, leading to groups being under-represented in decisionmaking at all levels or underserved. The realization of health equity and ultimate health and well-being demands identification and elimination of the inequities that lead to disparities in people’s health and well-being.

The resurgence of VPDs across Africa and other LMICs can be highly regarded as a health equity perspective. Africa's health systems are characterized by a lot of health barriers such as inadequate funding, unavailability of services in a community and lack of culturally competent care and weak disease surveillance systems.Citation69 This is often linked to poor socioeconomic status of the people, low literacy levels, and many other determinants. These barriers lead to unmet healthcare needs such as delays in receiving appropriate care and inability to secure preventative services.

Evidence shows that countries whose health systems have adept levels of financing tend to have an upper hand in formulating global policies that shape the distribution of health resources and eventually health outcomes.Citation70,Citation71 Countries with high demand for health and limited finance for health tend to experience dire health consequences and eventually poor health outcomes.Citation72,Citation73 Such health disparities are clearer during the times of pandemics. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed gross social and racial discrimination in global health, with high-income countries having timely and adequate access to vaccines and quality health care as compared to LMICs.Citation54 Most African countries did not have access to COVID-19 vaccines despite developed countries having received two to three doses of the same vaccine.

Inequities in vaccination still exist despite the WHO recognizing equity as the guiding principle in all of the priority areas identified in the WHO’s 13th General Programme of Work, 2019–2023, which aims to ensure healthy lives and well-being for all, leaving no one behind.Citation66,Citation74 Most vulnerable communities and individuals at greatest risk of VPDs across Africa still struggle to access timely and adequate vaccination owing to the multiple bottlenecks described above.

Furthermore, VPDs such as measles, polio, rubella and diphtheria disproportionately affect vulnerable communities with low socioeconomic status and limited access to essential healthcare services.Citation1 These inequalities in health and vaccination coverage can lead to serious ramifications such as resurgence of VPDs of epidemic potential.

Tackling VPDs in Africa: the need for a multi-strategic approach

In plight of the factors discussed above, tackling the resurgence of VPDs in Africa requires multiple strategies including strengthening disease surveillance, promoting health equity, boosting local vaccine manufacturing, stronger priority setting, policy support for decisionmakers, and capacity building. In this chapter, we discuss some of the factors for addressing the resurgence and reemergence of VPDs in Africa.

Strengthening VPDs surveillance in the African region

The resurgence and reemergence of VPDs calls for efficient and effective disease surveillance systems. Maintaining high-quality VPD surveillance is crucial for a rapid and timely response to VPD outbreaks, particularly in areas known to be vulnerable and prone to VPDs. In 2017, the African Heads of State endorsed the Addis Declaration on Immunization (ADI) at the 28th AU Summit. Among the 10 Addis Commitments, one aimed at “attaining and maintaining high-quality surveillance for targeted vaccine-preventable diseases.”Citation75

Within the African region, surveillance of VPDs is implemented in the context of the regional Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) strategy.Citation76 WHO developed the IDSR approach for improving public health surveillance and response by linking community, health facility, district and national levels. The IDSR promotes the rational and efficient use of resources by integrating and streamlining common surveillance activities. However, over the past two decades, VPD surveillance in the African region has been largely supported by funding from the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI).Citation76 With the GPEI drawing closer to eradicating polio, its budget has decreased substantially, and continues to decrease with time. Funding for VPD surveillance (e.g., measles, new vaccines, sentinel surveillance for rotavirus, invasive pneumococcal diseases) has declined markedly over the years.Citation76 This poses a major risk to the fight against VPDs in epidemic-prone areas.

Furthermore, Africa has been hardly hit with multiple epidemics in the past few years coupled with the devastating impact of climate change in the region.Citation77 Tackling VPDs in the era of multiple epidemics has been largely challenging. The surge in VPDs across Africa during the times of epidemics appears to be a common trend in Africa.Citation77,Citation78 In most cases, African health systems are largely overstretched during large epidemics and natural disasters, leading to decrease in vaccination coverage and resurgence of VPDs. For instance, in 2021, the WHO reported that nearly 25 million children missed their first measles dose, 5 million more than in 2019.Citation79 The drop in childhood immunizations was partly attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic which had caused significant interruptions in public health services delivery and reduced vaccination coverage. This underscores the importance of having robust and effective disease surveillance systems that remain effective even amidst external shocks.

The current global epidemic has prompted more regional and international organizations to invest in disease surveillance in Africa. The Africa CDC with support from the AU, runs the Surveillance and Disease Intelligence program with the goal of assisting AU Member States in developing a surveillance workforce capable of handling national surveillance responsibilities. Even though the program focuses on all disease outbreaks, its role in surveillance of VPDs cannot be disputed. Event-based surveillance promoted by the African CDC forms an important mechanism for early warning, risk assessment, disease predictions, and response.

Health equity and inclusion in tackling the re-emergence of VPDs

The reemergence of VPDs across the globe reflects various health inequities that need to be tackled to curtail the problem. Historically, VPDs including Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) outbreaks, varicella, pneumococcal disease, measles, polio, and pertussis (whooping cough) have disproportionally affected the poor vulnerable communities more than the rich.Citation1 The coming in of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019/2020 further exposed the existing health inequities. While developed countries achieved good control in the prevention of VPDs, most of these diseases have been endemic, with intermittent outbreaks in LMICs including Africa.Citation1

Inequitable distribution and limited access to basic and essential life resources remains one of the key drivers of resurgence of VPDs across Africa.Citation12 Despite the WHO launch of the EPI with the aim of achieving universal access to all relevant vaccines, in 1974 and establishment of the GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance in 2000 with the goal of providing vaccines to save lives and protect public health, several areas of the world are facing serious challenges, such as wars, poverty, inexistent infrastructures for vaccine manufacturing or difficulties in receiving imported vaccines.Citation80

Even though Africa holds the largest burden of infectious diseases, only 1% of the vaccines are manufactured within the continent.Citation81 In times of pandemics, such as that of the COVID-19, this creates major delays in the acquisition and distribution of essential vaccines, and eventual resurgence of VPDs. For instance, disruptions in the vaccine supply chain during the COVID-19 pandemic led to an increase in the number of VPDs such as measles, polio, yellow fever and others.Citation2,Citation82 Even though the global vaccination coverage decreased from 86% in 2019 to 83% in 2020, the drivers of such a drop are quite different between high-income countries and LMIC.Citation83 In developing countries, several contributing factors led to this recent trend, including the antivaccination movement, vaccine hesitancy, resource shortages, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.Citation80

While significant progress has been made in the fight against infectious diseases, global vaccine distribution, and vaccine manufacturing for emerging and existing diseases, these gains can only be sustained if we make deliberate efforts to address existing inequities.

Boosting local vaccine manufacturing

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the need for self-sufficient healthcare systems worldwide, especially focusing on the production of vaccines. Africa, a continent with more than 1.3 billion people has relied heavily on outside sources for vaccines, making it vulnerable to disruptions in the supply chain and international influences.Citation84,Citation85 Enhancing vaccine production in Africa is not only crucial for healthcare but essential for the region’s economic and public health security. It is essential for boosting local vaccine availability, supply and timely distributions during major global crisis, thereby aiding the prevention of resurgence of VPDs. To achieve this objective a strategy involving infrastructure enhancement, skill development, reinforcement, financial support and global cooperation is necessary.

Improving vaccine production in Africa needs to start with creating manufacturing plants.Citation84,Citation85 Many current facilities are outdated and not up to the standards needed for making vaccines today. It is important for governments and businesses to work together to construct facilities that have the technology. By forming partnerships between the private sectors, we can benefit from the efficiency of companies and the support of public resources. Moreover, setting up manufacturing hubs in regions can serve countries, efficiently making better use of resources and achieving cost savings through economies of scale.

Whilst establishing and expanding local vaccine manufacturing capacity remains crucial, robust regulatory frameworks also need to be established to ensure that vaccines are safe, effective and of top quality. This will ensure that immunized children have access to high quality, standard vaccines, which offer adequate immunity against VPDS. African nations should bolster their bodies by providing resources and independence. Aligning regulations, across the continent can simplify the approval process and promote smoother vaccine distribution, between countries. The African Medicines Agency (AMA) tasked with improving consistency and supervision should be empowered to take a role in this endeavor. Additionally, embracing practices and standards will boost the reputation of vaccines manufactured in Africa on a worldwide scale.

Starting and maintaining vaccine production, in Africa demands a strong commitment. Governments need to set aside funds dedicated to this cause in their budgets.Citation86,Citation87 Nonetheless, due to the limitations in many African nations, it is crucial for international financial institutions, donor agencies and charitable organizations to intervene and fill the funding gap. Exploring financing methods which combines public and private investments could also be considered. Creating a business environment with perks, like tax incentives and grants can entice investors to participate in this industry.

Effective partnerships play a role in driving the success of vaccine production projects in Africa. Teaming up with foreign vaccine manufacturers can bring in technical know-how and guidance to enhance local capacity. These partnerships can take various forms, such as ventures, technology sharing deals and licensing agreements. Additional international bodies, like the WHO and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance stand ready to provide backing through support, technical aid and policy advice.

A sustainable vaccine manufacturing ecosystem must be underpinned by robust research and development capabilities.Citation88,Citation89 African countries should invest in research and development to innovate and develop vaccines tailored to the specific health needs of their populations. Establishing centers of excellence in biotechnology and vaccine research can drive innovation and provide a pipeline of new vaccines. Collaboration with global research institutions can enhance these efforts, providing access to cutting-edge research and development methodologies

Stronger priority setting, policy support for decisionmakers, and capacity building

It is also important to prioritize improving vaccine production and acquisition. With the continent’s varying needs and scarce resources, a focused strategy is vital. The initial step is to pinpoint and prioritize diseases with an impact on health. Conducting a comprehensive disease burden analysis allows decisionmakers to allocate resources efficiently. This analysis should consider morbidity and mortality rates, economic impact, and the potential for epidemic outbreaks.Citation88 Prioritizing diseases based on this data ensures that the most pressing health issues are addressed first, maximizing public health benefits.

Involving stakeholders such as government entities, healthcare professionals, researchers and the local community is crucial in establishing priorities. Working together helps ensure that the identified priorities are in line with health objectives and cater to the needs of the community. These stakeholders can offer perspectives on health issues within their region and play a key role in developing an adaptable and inclusive plan, for vaccine production.

By using decisionmaking frameworks based on evidence, we can make sure that our priorities are well informed by data and best practices. This includes looking at health trends advancements, in technology and successful vaccination efforts, in parts of the world. By following strategies that have been proven effective, African nations can improve how they make decisions and use their resources efficiently.

It is crucial to match policies and funding with the priorities that have been identified to ensure execution. Governments need to establish policy frameworks that back vaccine production efforts, such as standards, tax benefits and investments, in research and development. Directing resources toward areas of priority can speed up advancements and maintain long-term projects effectively.

Effective policy support is a cornerstone of boosting equitable vaccine manufacturing and distribution in Africa. Policies provide the necessary framework for guiding actions, securing investments, and ensuring regulatory compliance. To create an enabling environment for efficient vaccine manufacturing and distribution, comprehensive and supportive policies are essential.

To encourage businesses to invest, governments should introduce measures, like tax incentives, subsidies and financial aid for vaccine producers. These benefits can ease the strain on companies, motivating them to set up vaccine manufacturing plants in Africa. Furthermore, establishing designated zones for pharmaceutical sectors can foster an atmosphere for progress and creativity.

Developing specialized education and training programs is crucial for creating a skilled workforce. Universities and technical institutes should offer courses in biotechnology, pharmaceutical sciences, and vaccine production. Collaborating with international institutions can provide access to advanced training and best practices. Continuous professional development programs can ensure that existing professionals stay updated with the latest advancements in vaccine technology.

Proficiency in vaccine manufacturing requires an understanding of production procedures, quality assurance and adherence to regulations. Training initiatives should emphasize hands on learning and practical experience to cultivate these competencies. Setting up training facilities and workshops can enhance skill acquisition. Additionally, it is imperative to encourage the exchange of knowledge among professionals.

Strengthening institutions involved in vaccine manufacturing is essential for ensuring efficiency and quality. This includes enhancing the capabilities of regulatory agencies, research institutions, and manufacturing facilities. Providing adequate resources, infrastructure, and autonomy to these institutions can enable them to operate effectively and support the broader vaccine manufacturing ecosystem.

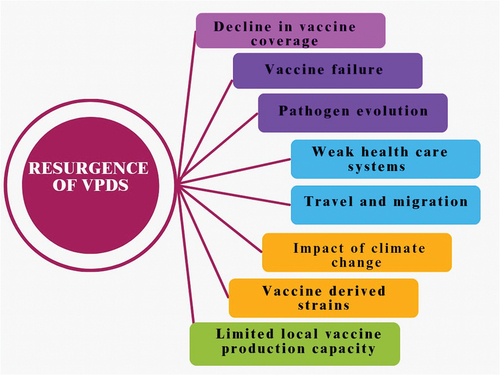

To enhance vaccine production and distribution in order to overcome inequities associated with VPDs in Africa, a thorough and well-thought-out approach is needed. This involves setting priorities, establishing policies and investing in building capabilities. Identifying diseases through analysis of their impact, involving all stakeholders and aligning resources and regulations are crucial initial steps. Implementing policies such as frameworks, incentives, partnerships between public and private sectors, research and development support, intellectual property management and international cooperation lays a solid groundwork for progress. Strengthening education systems, providing training opportunities, improving institutions capabilities, sharing knowledge effectively, investing in research and development activities, ensuring quality control standards are met and securing funding sources are all essential for nurturing a skilled workforce and creating resilient manufacturing structures. By implementing these strategies, the landscape of vaccine production in Africa can undergo improvements that will not only bolster public health safety but also promote fairness, in global healthcare access. summarizes the strategies for tackling vaccine-preventable diseases in the WHO African region.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the reemergence of VPDs undermines the significant strides that have been made in the fight against VPDs. It is a multifactorial challenge. To address this escalating health concern, it is vital to address the specific contributing factors, which include health inequity and vaccine hesitancy. There is a need for strong priority setting by the government, strong procurement and supply chain systems backed by a strong policy framework to support timely purchasing and distribution of vaccines during pandemics. In addition, it is essential to strengthen the health systems in African countries. Well-functioning health systems, including strong governance, stable financing, and a dedicated healthcare workforce, are critical for dealing with any emerging health threats.

Author contributions

AFL & ANB; Conceptualization, design, manuscript writing, and editing. All authors contributed to manuscript writing, proofreading and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and material

All materials used for preparation of this manuscript are available upon request from the corresponding author

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rodrigues CMC, Plotkin SA. Impact of vaccines; health, economic and social perspectives. Front Microbiol. 2020;11. doi:10.3389/FMICB.2020.01526.

- Lubanga AF, Bwanali AN, Munthali L, Mphepo M, Chumbi GD, Kangoma M, Khuluza C. Malawi vaccination drive: an integrated immunization campaign against typhoid, measles, rubella, and polio; health benefits and potential challenges. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(2). doi:10.1080/21645515.2023.2233397.

- Immunization | WHO | Regional Office for Africa. https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/immunization.

- Sheahan KL, Speizer I, Curtis S, Weinberger M, Paul J, Bennett AV. Influence of family planning and immunization services integration on contraceptive use and family planning information and knowledge among clients: a cross-sectional analysis in urban Nigeria. Front Glob Womens Health. 2022;3. doi:10.3389/fgwh.2022.859832.

- Huntington D, Aplogan A. The integration of family planning and childhood immunization services in Togo. Stud Fam Plann. 1994;25(3):176. doi:10.2307/2137943.

- Nelson AR, Cooper CM, Kamara S, Taylor ND, Zikeh T, Kanneh-Kesselly C, Fields R, Hossain I, Oseni L, Getahun BS, et al. Operationalizing integrated immunization and family planning services in rural Liberia: lessons learned from evaluating service quality and utilization. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019;7(3):418–114. doi:10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00012.

- Sheahan KL, Orgill-Meyer J, Speizer IS, Curtis S, Paul J, Weinberger M, Bennett AV. Development of integration indexes to determine the extent of family planning and child immunization services integration in health facilities in urban areas of Nigeria. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1). doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01105-y.

- Sheahan KL, Speizer IS, Orgill-Meyer J, Curtis S, Weinberger M, Paul J, Bennett AV. Facility-level characteristics associated with family planning and child immunization services integration in urban areas of Nigeria: a longitudinal analysis. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11436-x.

- Greenwood B. The contribution of vaccination to global health: past, present and future. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2014;369(1645):20130433. doi:10.1098/RSTB.2013.0433.

- A database of local vaccine manufacturing commitments and tech-transfers - Clinton health access initiative. https://www.clintonhealthaccess.org/database/a-database-of-local-vaccine-manufacturing-commitments-and-tech-transfers/.

- Gray A, Sharara F. Global and regional sepsis and infectious syndrome mortality in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10:S2. doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(22)00131-0.

- Azevedo MJ. The state of health system(s) in Africa: challenges and opportunities. Afr Histories Modernities. 2017; 1–73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32564-4_1.

- Feldman AG, O’Leary ST, Danziger-Isakov L. The risk of resurgence in vaccine-preventable infections due to coronavirus disease 2019—related gaps in immunization. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(10):1920–3. doi:10.1093/CID/CIAB127.

- Dabbagh A, Laws RL, Steulet C, Dumolard L, Mulders MN, Kretsinger K, Alexander JP, Rota PA, Goodson JL. Progress toward regional measles elimination — worldwide, 2000–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;67(47):1323–9. doi:10.15585/MMWR.MM6747A6.

- Masresha BG, Hatcher C, Lebo E, Tanifum P, Bwaka AM, Minta AA, Antoni S, Grant GB, Perry RT, O’Connor P. Progress toward measles elimination — African Region, 2017–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(36):985–91. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7236a3.

- Machingaidze S, Wiysonge CS, Hussey GD. Strengthening the expanded programme on immunization in Africa: looking beyond 2015. PLOS Med. 2013;10(3):e1001405. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001405.

- Uwizihiwe JP. 40th anniversary of introduction of Expanded Immunization Program (EPI): a literature review of introduction of new vaccines for routine childhood immunization in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Vaccines & Vaccination. 2015;1(1). doi:10.15406/ijvv.2015.01.00004.

- Dixon MG, Ferrari MAS, Antoni S, Li X, Portnoy A, Lambert B, Hauryski S, Hatcher C, Nedelec Y, Patel M, et al. Progress toward regional measles elimination — worldwide, 2000 – 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;70(45):1563–9. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7045a1.

- Patel MK, Gacic-Dobo M, Strebel PM, Dabbagh A, Mulders MN, Okwo-Bele J-M, Dumolard L, Rota PA, Kretsinger K, Goodson JL. Morbidity and mortality weekly report progress toward regional measles elimination-worldwide, 2000-2015. 2016.

- Measles – Africa CDC. https://africacdc.org/disease/measles/.

- Focus Lubanga A, Bwanali N, Munthali L, Mphepo M, Chumbi GD, Kangoma M, Khuluza C. Malawi vaccination drive: an integrated immunization campaign against typhoid, measles, rubella, and polio; health benefits and potential challenges. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2023;19(2). doi:10.1080/21645515.2023.2233397.

- WHO: WHO | Poliomyelitis. WHO; 2020.

- Hepatitis B. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b.

- Fast facts on global immunization. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/immunization/data/fast-facts.html.

- Frenkel LD. The global burden of vaccine-preventable infectious diseases in children less than 5 years of age: Implications for COVID-19 vaccination. How can we do better? Allergy Asthma Proc. 2021;42(5):378–85. doi:10.2500/AAP.2021.42.210065.

- Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization. https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/policies/position-papers.

- Masresha BG, Hatcher C, Lebo E, Tanifum P, Bwaka AM, Minta AA, Antoni S, Grant GB, Perry RT, O’Connor P. Progress toward measles elimination — African Region, 2017–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(36):985–91. doi:10.15585/MMWR.MM7236A3.

- Malawi – GPEI. https://polioeradication.org/where-we-work/malawi/.

- Masresha B, Shibeshi M, Kaiser R, Luce R, Katsande R, Mihigo R. Congenital Rubella syndrome in the African region - data from sentinel surveillance. J Immunol Sci Suppl. 2018;2(SI1):145–9. doi:10.29245/2578-3009/2018/si.1122.

- Spearman CW, Afihene M, Ally R, Apica B, Awuku Y, Cunha L, Dusheiko G, Gogela N, Kassianides C, Kew M, et al. Hepatitis B in sub-Saharan Africa: strategies to achieve the 2030 elimination targets. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(12):900. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30295-9.

- Clarke KEN, MacNeil A, Hadler S, Scott C, Tiwari TSP, Cherian T. Global epidemiology of Diphtheria, 2000–2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(10):1834. doi:10.3201/EID2510.190271.

- Diphtheria-Nigeria. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON452.

- WHO. WHO and UNICEF warn of a decline in vaccinations during COVID-19. Geneva: World Health organization; 2020.

- Greenlee CJ, Newton SS. A review of traditional vaccine-preventable diseases and the potential impact on the otolaryngologist. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;22(03):317–29. doi:10.1055/S-0037-1604055.

- Weak Vaccine-Preventable Disease Surveillance Could Cost the African Region $22.4 billion over the next decade, WHO Warns - World | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/weak-vaccine-preventable-disease-surveillance-could-cost-african-region-224-billion.

- IJERPH | Special Issue : Re-Emergence of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph/special_issues/REVPD.

- Ogundele OA, Omotoso AA, Fagbemi AT. COVID-19 outbreak: a potential threat to routine vaccination programme activities in Nigeria. Hum Vaccines Immunotherapeutics. 2021;17(3):661–3. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1815490.

- Chukwu OA, Kapiriri L, Essue B. Supporting the pandemic response and timely access to COVID-19 vaccines: a case for stronger priority setting and health system governance in Nigeria. Int J Pharm Pract. 2022;30(3):284–7. doi:10.1093/ijpp/riac028.

- Hungerford D, Cunliffe NA. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) – impact on vaccine preventable diseases. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(18). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.18.2000756.

- Nchasi G, Paul IK, Sospeter SB, Mallya MR, Ruaichi J, Malunga J. Measles outbreak in sub-Saharan Africa amidst COVID-19: a rising concern, efforts, challenges, and future recommendations. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;81. doi:10.1016/J.AMSU.2022.104264.

- Bangura JB, Xiao S, Qiu D, Ouyang F, Chen L. Barriers to childhood immunization in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1). doi:10.1186/S12889-020-09169-4.

- Uthman OA, Sambala EZ, Adamu AA, Ndwandwe D, Wiyeh AB, Olukade T, Bishwajit G, Yaya S, Okwo-Bele JM, Wiysonge CS. Does it really matter where you live? A multilevel analysis of factors associated with missed opportunities for vaccination in sub-Saharan Africa. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(10):2397. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1504524.

- Trotter CL, Lingani C, Fernandez K, Cooper LV, Bita A, Tevi-Benissan C, Ronveaux O, Préziosi MP, Stuart JM. Impact of MenAfriVac in nine countries of the African meningitis belt, 2010–15: an analysis of surveillance data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(8):867–72. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30301-8.

- Mallory ML, Lindesmith LC, Baric RS. Vaccination-induced herd immunity: Successes and challenges. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(1):64–6. doi:10.1016/J.JACI.2018.05.007.

- De Cellès MD, Riolo MA, Magpantay FMG, Rohani P, King AA. Epidemiological evidence for herd immunity induced by acellular pertussis vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(7). doi:10.1073/PNAS.1323795111.

- Progress reports. https://www.gavi.org/programmes-impact/our-impact/progress-reports.

- Focus Lubanga A, Bwanali N, Kambiri F, Harawa G, Mudenda S, Mpinganjira SL, Singano N, Makole T, Kapatsa T, Kamayani M, et al. Expert review of anti-infective therapy tackling antimicrobial resistance in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities for implementing the new people-centered WHO guidelines Tackling antimicrobial resistance in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities for implementing the new people-centered WHO guidelines. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2024; doi:10.1080/14787210.2024.2362270.

- Bigdeli M, Peters DH, Wagner AK. Medicines in health systems: advancing access, affordability and appropriate use. Columbia: Columbia University Libraries; 2014.

- Ewuoso C. What COVID-19 vaccine distribution disparity reveals about solidarity. Vaccine Distribution Disparity Solidarity, Voices In Bioethics. 2024;10. doi:10.52214/vib.v10i.12042.

- Niohuru I. Healthcare and Disease Burden in Africa. England: Springer; 2023.

- Shimizu K, Checchi F, Warsame A. Disparities in health financing allocation among infectious diseases in Ebola Virus Disease (EVD)-affected countries, 2005–2017. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(2):179. doi:10.3390/HEALTHCARE10020179.

- Domo NR, Nuolabong C, Nyarko KM, Kenu E, Balagumyetime P, Konnyebal G, Noora CL, Ameme KD, Wurapa F, Afari E. Uncommon mixed outbreak of pneumococcal and meningococcal meningitis in Jirapa District, Upper West Region, Ghana, 2016. Ghana Med J. 2017;51(4):149. doi:10.4314/gmj.v51i4.2.

- Gautret P, Botelho-Nevers E, Brouqui P, Parola P. The spread of vaccine-preventable diseases by international travellers: a public-health concern. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(Suppl 5):77–84. doi:10.1111/J.1469-0691.2012.03940.X.

- Makenga G, Bonoli S, Montomoli E, Carrier T, Auerbach J. Vaccine production in Africa: a feasible business model for capacity building and sustainable new vaccine introduction. Front Public Health. 2019;7. doi:10.3389/FPUBH.2019.00056.

- Ali I, Hamid S. Implications of COVID-19 and “super floods” for routine vaccination in Pakistan: the reemergence of vaccine preventable-diseases such as polio and measles. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(7). doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2154099.

- Sodjinou VD, Mengouo MN, Douba A, Tanifum P, Yapi MD, Kuzanwa KR, Otomba JS, Masresha B. Epidemiological characteristics of a protracted and widespread measles outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 2018-2020. Pan Afr Med J. 2022;42. doi:10.11604/pamj.2022.42.282.34410.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). The impact of violence against health care on the health of children and mothers acase study in three health zones in eastern DRC 2. 2024.

- Kayembe HC, Bompangue D, Linard C, Mandja BA, Batumbo D, Matunga M, Muwonga J, Moutschen M, Situakibanza H, Ozer P, et al. Drivers of the dynamics of the spread of cholera in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2000–2018: an eco-epidemiological study. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17(8):e0011597. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0011597.

- Roberts L. Why measles deaths are surging — and coronavirus could make it worse. Nature. 2020;580(7804):446–7. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01011-6.

- Mbaeyi C, Moran T, Wadood Z, Ather F, Sykes E, Nikulin J, Al Safadi M, Stehling-Ariza T, Zomahoun L, Ismaili A, et al. Stopping a polio outbreak in the midst of war: lessons from Syria. Vaccine. 2021;39(28):3717–23. doi:10.1016/J.VACCINE.2021.05.045.

- Focus Adriano L, Nazir A, Uwishema O. The devastating effect of cyclone Freddy amidst the deadliest cholera outbreak in Malawi: a double burden for an already weak healthcare system—short communication. Ann Of Med & Surg. 2023;85(7):3761–3. doi:10.1097/ms9.0000000000000961.

- Lubanga AF, Bwanali AN, Munthali L, Chumbi GD, Mphepo M. What should be Malawi’s goal in cholera control and prevention? Lessons from the deadliest cholera outbreak in two decades. Int J Surg: Global Health. 2023;6(5). doi:10.1097/gh9.0000000000000300.

- Roberts L. Africa battles out-of-control polio outbreaks. Science. 2022;375(6585):1079–80. doi:10.1126/SCIENCE.ADB1920.

- Guglielmi G. Africa declared free from wild polio - but vaccine-derived strains remain. Nature. 2020; doi:10.1038/D41586-020-02501-3.

- Health equity. https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-equity#tab=tab_1.

- Shim RS, Compton MT. Addressing the social determinants of mental health: if not now, when? If not us, who? Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(8):844–6. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201800060.

- Rodriguez D. WHO | About Social Determinants Of Health. Geneva: World Health organization; 2017.

- Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, Bloomer E, Goldblatt P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet. 2012;380(9846):1011–29. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8.

- Azevedo MJ. Historical perspectives on the state of health and health systems in Africa. Vol. II. 2017. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32564-4.

- Osewe PL, Peters MA. Prioritizing global public health investments for COVID-19 response in real time: results from a delphi exercise. Health Secur. 2022;20(2):137–46. doi:10.1089/hs.2021.0142.

- Kutzin J, Witter S, Jowett M, Bayarsaikhan D. Developing a national health financing strategy: a reference guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Tandon A, Reddy KS. Redistribution and the health financing transition. J Glob Health. 2021;11:16002. doi:10.7189/JOGH.11.16001.

- Spicer N, Agyepong I, Ottersen T, Jahn A, Ooms G. ‘It’s far too complicated’: why fragmentation persists in global health. Global Health. 2020;16(1). doi:10.1186/S12992-020-00592-1.

- Wariri O, Edem B, Nkereuwem E, Nkereuwem OO, Umeh G, Clark E, Idoko OT, Nomhwange T, Kampmann B. Tracking coverage, dropout and multidimensional equity gaps in immunisation systems in West Africa, 2000–2017. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(5):e001713. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001713.

- WHO EMRO | Historic commitment from African Heads of State to advance immunization in Africa | News | Media centre. https://www.emro.who.int/media/news/historic-commitment-from-african-heads-of-state-to-advance-immunization-in-africa.html.

- Investment case for vaccine-preventable diseases surveillance in the African Region. 2019.

- The greater Horn of Africa’s climate-related health crisis worsens as disease outbreaks surge | WHO | Regional Office for Africa. https://www.afro.who.int/news/greater-horn-africas-climate-related-health-crisis-worsens-disease-outbreaks-surge.

- Focus Adriano L, Nazir A, Uwishema O. The devastating effect of cyclone Freddy amidst the deadliest cholera outbreak in Malawi: a double burden for an already weak healthcare system—short communication. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023;85(7):3761–3. doi:10.1097/MS9.0000000000000961.

- COVID-19 pandemic fuels largest continued backslide in vaccinations in three decades. https://www.who.int/news/item/15-07-2022-covid-19-pandemic-fuels-largest-continued-backslide-in-vaccinations-in-three-decades.

- Borba RCN, Vidal VM, Moreira LDO. The re-emergency and persistence of vaccine preventable diseases. An Acad Bras Ciênc. 2015;87(2 suppl):1311–22. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201520140663.

- Current and planned vaccine manufacturing in Africa - Clinton health access initiative. https://www.clintonhealthaccess.org/report/current-and-planned-vaccine-manufacturing-in-africa/.

- Oduoye MO, Zuhair V, Marbell A, Olatunji GD, Khan AA, Farooq A, Jamiu AT, Karim KA. The recent measles outbreak in South African Region is due to low vaccination coverage. What should we do to mitigate it? New Microbes New Infect. 2023;54:101164. doi:10.1016/J.NMNI.2023.101164.

- Basu S, Ashok G, Debroy R, Ramaiah S, Livingstone P, Anbarasu A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on routine vaccine landscape: a global perspective. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(1). doi:10.1080/21645515.2023.2199656.

- Scaling Up African vaccine manufacturing capacity perspectives from the African vaccine-manufacturing industry on the challenges and the need for support. 2023.

- Saied AA, Metwally AA, Dhawan M, Choudhary OP, Aiash H. Strengthening vaccines and medicines manufacturing capabilities in Africa: challenges and perspectives. EMBO Mol Med. 2022;14(8). doi:10.15252/emmm.202216287.

- Souliotis K, Grima S, Makenga G, Bonoli S, Montomoli E, Carrier T, Auerbach J. Vaccine production in Africa: a feasible business model for capacity building and sustainable new vaccine introduction. Front Public Health. 2019;7:56. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2019.00056.

- Kumraj G, Pathak S, Shah S, Majumder P, Jain J, Bhati D, Hanif S, Mukherjee S, Ahmed S. Capacity building for vaccine manufacturing across developing countries: the way forward. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(1). doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2020529.

- John-Joy Owolade A, Oluwaseun Sokunbi T, Oluwatobi Aremu F, Oluwatosin Omotosho E, Abai Sunday B, Adebayo Adebisi Y, Ekpenyong A, Opeyemi Babatunde A. Strengthening Africa’s capacity for vaccine research: needs and challenges. Tabriz Univ Of Med Sci. 2022;12(3):282–285. doi:10.34172/hpp.2022.36.

- Akegbe H, Onyeaka H, Michael Mazi I, Alex Olowolafe O, Dolapo Omotosho A, Olatunji Oladunjoye I, Amuda Tajudeen Y, Seun Ofeh A. The need for Africa to develop capacity for vaccinology as a means of curbing antimicrobial resistance. Vaccine: X. 2023;14:100320. doi:10.1016/j.jvacx.2023.100320.