?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

It was common to see that older adults were reluctant to be vaccinated for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. There is a lack of practical prediction models to guide COVID-19 vaccination program. A nationwide, self-reported, cross-sectional survey was conducted from September 2022 to November 2022, including people aged 60 years or older. Stratified random sampling was used to divide the dataset into derivation, validation, and test datasets at a ratio of 6:2:2. Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator and multivariable logistic regression were used for variable screening and model construction. Discrimination and calibration were assessed primarily by area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) and calibration curve. A total of 35057 samples (53.65% males and mean age of 69.64 ± 7.24 years) were finally selected, which constitutes 93.73% of the valid samples. From 33 potential predictors, 19 variables were screened and included in the multivariable logistic regression model. The mean AUC in the validation dataset was 0.802, with sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 0.732, 0.718 and 0.729 respectively, which were similar to the parameters in the test dataset of 0.755, 0.715 and 0.720, respectively, and the mean AUC in the test dataset was 0.815. There were no significant differences between the model predicted values and the actual observed values for calibration in these groups. The prediction model based on self-reported characteristics of older adults was developed that could be useful for predicting the willingness for COVID-19 vaccines, as well as providing recommendations in improving vaccine acceptance.

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies people aged 65 years and older as older adults, and China sets the definition at age of 60 years and older. Population Ageing is when the older people account for more than 7% of the country’s population.Citation1 China currently has the largest older population in number across the world.Citation2 According to the United Nations World Population Prospects 2022,Citation3 the size of China’s older population has continued to increase in the first half of the 21st century, whose number is expected to exceed 310 million by 2025, and the process of Population Ageing has picked up its pace while China’s fertility rate remained low and life expectancy rose.

Older people with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection were at increased risk of being hospitalized, enduring severe illness, and death.Citation4–6 As reported in some Chinese regional data, more than 90% of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related deaths in Shanghai occurred in unvaccinated older adults,Citation7 and 84.6% of deaths in Hong Kong occurred in older adults who were unvaccinated or had received only one dose.Citation8 A recent nationwide study published in Nature Medicine also found that 90% of COVID-19-related deaths occurred in older adults who had not been administered enough jabs of the vaccine.Citation9 In contrast, countries with significantly lower COVID-19-related mortality rates, such as Singapore and Japan, have successfully vaccinated over 95% of their older citizens.Citation10 Meanwhile, several studies have shown that vaccination was effective in reducing the risk of hospitalization and mortality.Citation11–13 The above emphasized the need for well-targeted protective measures on vulnerable aging group.

However, it was common to see that older people were reluctant to be vaccinated in China.Citation14,Citation15 This phenomenon was also observed around the world, despite the availability of free vaccination, a significant proportion of older adults in various countries and regions were still resistant to be vaccinated.Citation10,Citation16,Citation17 Data published by the National Health Commission of China indicatedCitation18 that by 23rd July 2022, one dose injection minimum in group of 60 years and older in China had reached 89.6%, and the progress of basic thorough immunization had reached 84.7%, with booster shots administered recording 67.3%. In breakdowns, the vaccinated rates for booster shots in people aged “60–69 years,” “70–79 years,” and “80 years and +” were 72.8%, 69.9%, and 38.4%, respectively. China’s vaccination rate for the elderly is relatively high, but the coverage of booster shots and vaccinations for the elderly aged 80 years and above still need to be improved.Citation19 Several studies have shown that cognitive and social factors play important roles in COVID-19 vaccination in the older adults, including suspicions to the vaccine’s efficacy and safety, misperception to the risk of infection, lack of trust in medical personnel, religious beliefs, promotional activities, and others.Citation9,Citation19–21 Moreover, the distribution pattern of influencing factors differs from that in other populations, which requires the development of targeted strategies for the older people.

China have not vaccinated enough its older people against COVID-19, and there are four areas remaining unaddressed: 1) given the nature of the SARS-CoV-2 to mutate and immune escape, it is crucial to establish science-based vaccination programs and timely measures to prepare for the next wave of SARS-CoV-2 outbreak; 2) It is vital to understand the behavioral factors and conduct comprehensive review on individual’s response to vaccination; 3) In addition to identifying the various determinants to receive COVID-19 vaccination, China’s unique cultural characteristics in both national level and community level are another essential area worthy of consideration; 4) There is a lack of practical prediction models to guide COVID-19 vaccination considering social and cognitive factors among the older population in China. Therefore, this study aimed to develop and validate a prediction model for vaccination intentions against COVID-19 based on demographic characteristics and cognitive factors of the older adults in China.

Design

This study was a nationwide cross-sectional survey conducted from September 2022 to November 2022, with inclusion criteria defined as people aged 60 years or older, and the primary outcome defined as the self-reported willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Multi-stage stratified random sampling and on-site questionnaire surveys were carried out, where urban areas (municipalities/provincial capitals/medium-sized cities) and counties (including townships and rural areas) were ranked according to gross domestic product (GDP) per capita into high and low stratifications, respectively, and the areas were randomly selected using random number method.

For the research aim of exploring the factors influencing vaccination in population level, it was planned to complete 62,000 questionnaires on vaccination and awareness in people ≥60 years older based on the estimated willingness of 35.0% to vaccinate against pneumococcus, with 2,000 people surveyed in each province (1,000 people each in urban and rural areas). Meanwhile, the sample size calculation for predictive model could be calculated as a lower bound using the 10epv principle. As 30 variables were estimated, at least 300 samples will be included. Based on the response rate of about 80%, the lower bound for the total sample size were 375.

The questionnaire for this study was developed by our expert group, comprising clinicians, epidemiologists, statisticians, and researchers from the Chinese Association of Geriatric Research, with input from prior literature.Citation21–24 Prior to its wider distribution, the questionnaire underwent a pilot test with a regional sample, during which it was refined based on feedback.

Participants filled out the e-questionnaire by scanning the QR code, and the e-questionnaire was technically supported by WJX.CN, the online service provider. The electronic questionnaires were set up primarily for ease of statistical recovery and analysis, rather than being used for direct online distribution of documents for completion.

At the beginning of the survey, the survey project team sent survey-related information such as survey process, questionnaire, and special notice through the online survey platform to the surveyed population on site, while all selected individuals were provided with an e-informed consent. The respondents completed all the survey questions, either independently or under the assistance of the surveyor, and were unable to submit the questionnaire to the platform upon completing answering questions. The questionnaire review and qualification screening were then conducted by the quality control staff, and the qualified questionnaires were reserved for analysis. outlines the core questionnaire contents.

Table 1. Core questionnaire questions and variable screening process using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression.

Based on stratified random sampling, the whole dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets with a 6:2:2 ratio to ensure representativeness of the whole population. The training set is used to train the model and estimate the model parameters. The validation set is used to preliminarily assess the model’s performance and to find important parameters and optimal threshold. The validation set is used to evaluate the model’s generalization ability.

The regression coefficients, odds ratios (ORs), and confidence intervals (CIs) of the logistic regression model were estimated using the training set. The model performance was evaluated, and parameters were adjusted using the validation set. Finally, the model’s generalization ability was assessed using the test set.

The Ethics Committee approved this study with the approval number (2022-KY-135).

Statistical analysis

The survey underwent statistical analysis and modeling using R 4.3.2. A two-sided P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and median, while categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage. Missing values were removed.

In the development dataset, all cases underwent variable screening using the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression.Citation25 The regularization parameter (λ), which controlled the model’s complexity by shrinking the coefficients toward zero, was determined through cross-validation, balancing the error and number of variables.Citation26 A penalty was applied to weaker factors, to contract the latter toward zero. This resulted in only the strongest predictors being retained in the model. The regularization parameter lambda for LASSO was determined using 10-fold cross-validation to reduce model complexity and prevent overfitting. LASSO regression was performed using the “glmnet” R package (4.1–8) to incorporate the variables selected through LASSO variable selection into the multivariable logistic regression model.

The evaluation of model performance primarily involved constructing a receiver operating curve (ROC) and a calibration curve, as well as assessing indicators such as the area under the ROC (AUC), accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, and calibration. The AUC was used to evaluate the degree of differentiation, while the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to examine the degree of calibration.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the included population

Out of the 44,446 questionnaires, we excluded participants who declined to complete the questionnaire (n = 6145, 13.83%) and those who were uncertain about vaccination (n = 783, 1.76%). And 37,401 (84.15%) valid questionnaires were retrieved on November 4, 2022. For modeling analysis, samples with missing values were removed (n = 2344, 5.27%) during the data cleaning phase, resulting in 35,057 samples, which constitutes 93.73% of the valid samples and 78.87% of participants.

Among these respondents, 30,401(86.72%) received the vaccine, and 18,808 (53.65%) were male and 32,573 (92.91%) belong to Han Ethnicity. The education levels were as follows: elementary school or below (47.53%), junior high school (27.92%), high school/vocational school (16.76%), undergraduate (7.38%), and postgraduate or above (0.40%). About 45.43% of participants, equivalent to 15,925 people, were rural residents, while 19,232 people were not. Out of these participants 12,598 (35.43%) were employed in industries of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, fishery, and water conservancy production; 18874 (53.84%) have an annual family income less than 50,000 yuan. About 19.001 (54.20%) reported having chronic comorbidities ().

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of the included population in train dataset, validation dataset, and test dataset.

Variable screening and prediction model development

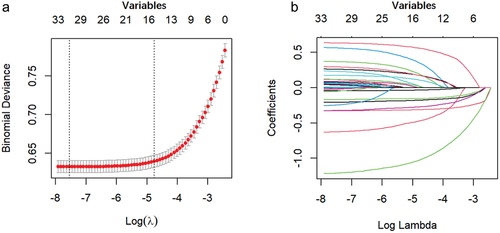

Thirty-three variables collected from the questionnaire were included in the LASSO regression. As the biased likelihood binomial deviation was minimized, the most appropriate tuning parameter for the LASSO regression was 0.055 (), and 19 variables were selected as significant predictors of COVID-19 vaccination, consisting of factors like “Age,” “Long-term residing place,” and “Chronic comorbidities.” In addition, opinions and perspectives were also brought in, including “Important for older adults to be vaccinated,” “Recommending vaccination to older neighbors,” “Vaccination safe/effective,” “Vaccination against religious beliefs and customs,” “Which vaccines considered respiratory-infectious-diseases-associated?,” “Which vaccines considered suitable for the elderly?,” and “Trust in advice by health workers?.” However, some variables were not included, such as “education,” “occupation before retirement,” “annual gross household income,” and “Active provision of vaccine-related information/advice by health workers.

Figure 1. Feature selection using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) binary logistic regression model.

Multivariable logistic regression

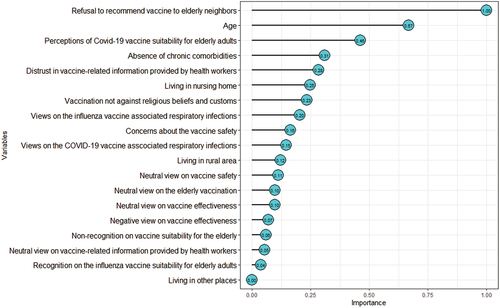

A total of 21,035 cases were included in the training dataset with a mean (SD) age of 69.72 (7.28) years, of which 53.56% were males, and 18,174 (86.4%) were eventually vaccinated. Nineteen variables were included in the multivariable logistic regression model and were eventually included in the prediction model. Apart from the “neutral view on vaccination effectiveness” (p = 0.13), other variables were statistically significant (p < 0.05) in predicting vaccination, and exhibits variables ranking in importance order. These variables included “Refusal to recommend vaccine to elderly neighbors” (OR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.265–0.326), Age (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.948–0.959), Recognition on vaccine suitability for the elderly” (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.651–2.025), “Absence of chronic comorbidities” (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.307–1.569), “Distrust in vaccine-related information provided by healthcare workers” (OR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.324–0.499), “Living in nursing home” (OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.463–0.650), “Vaccination not against religious beliefs and customs” (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.538–2.210), “Views on the influenza vaccine associated with respiratory infections” (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.089–1.328), “Concerns about the vaccine safety” (OR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.363–0.600), “Views on the COVID-19 vaccine associated with respiratory infections” (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.177–1.445), “Living in rural area” (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.103–1.316), “Neutral view on vaccine safety” (OR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.610–0.817), “Neutral view on the elderly vaccination” (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.678–0.877), “Negative view on vaccination effectiveness” (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.557–0.948), “Non-recognition on vaccine suitability for older adults” (OR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.573–0.887), “Neutral view on vaccine-related information provided by healthcare workers” (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.758–0.951), “Recognition on the influenza vaccine suitability for older adults” (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.092–1.344), and “Living in other places” (OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.172–0.759) ().

Figure 2. The importance of variables in multivariable logistic Model.

Table 3. Multivariable logistic regression included variables from the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression.

The binary logistic regression model was used to predict the probability of a binary response variable yi, where yi could be either 0 or 1 (standing for unvaccinated or vaccinated, respectively), based on a vector xi = [xi1,…,xik], i = 1, …, n, representing n samples with k predictor variables for each sample. The model could be expressed as:

The probability that the response variable yi equaled 1 given the sample characteristics was represented by Pr (yi = 1│xij, j = 1, …, k). The coefficients corresponding to the explanatory variables x1, …, xk were represented by β1, …, βk, with β0 being the intercept term (β0 = 4.84).

Use of the validation dataset to develop optimal thresholds

A total of 7011 cases were reserved as validation dataset with a mean (SD) age of 69.43 (7.13) years old, of which 53.72% were male and 6118 (87.3%) were eventually vaccinated. The mean AUC based on the validation dataset was 0.802 (), and the optimal threshold point for the ROC curve was selected to be 0.870 based on the Youden’s index, with a sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 0.732, 0.718, and 0.729, respectively. The calibration curve demonstrated the consistency between the model’s predicted probability and the observation, where the black solid line was closer to the gray ideal calibration mark (). There was no statistically significant difference between the model predicted values and the actual observed values (Hosmer–Lemeshow χ2 = 10.20, p = 0.25 > 0.05).

Performance of the prediction model in the test dataset

The test dataset was consisted of 7,011 participants with a mean (SD) age of 69.63 (7.21) years, of which 53.84% were males, and 6109 (87.1%) were eventually vaccinated. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the prediction model in the validation cohort were similar as those of the development dataset, with 0.755, 0.715, and 0.720, respectively, and the mean AUC in the test dataset was 0.815 (). The calibration curve for the probability of vaccination demonstrated a good agreement between prediction and the observation (). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test yielded a non-significant statistic (χ2 = 9.94, p = 0.27 > 0.05), indicating that there was no deviation from the optimal.

Discussions

Despite major government efforts to promote COVID-19 vaccination, the vaccination rate among the elderly remained relatively low. This may result from a low willingness to be vaccinated and insufficient consideration of social and cognitive factors. With the continuous mutation and spread of SARS-CoV-2, older people in China still face a significant risk of infection.Citation27 This study presented a validated prediction model for COVID-19 vaccination in the elderly population in China, based on a national, multicenter, self-reported survey. The model considers social and cognitive factors and demonstrates good prediction performance. To our knowledge, this was the first prediction model for COVID-19 vaccination in the older adults before China verged on the end of Zero-COVID policy.Citation28

The differentiation and calibration of the prediction model were satisfying, and the variables needed were usually easy to obtain. In this model, the top five variables in terms of prediction importance were “Refusal to recommend vaccination to elderly neighbors,” “Age,” “Recognition on COVID-19 vaccine suitability for older adults,” “Absence of chronic comorbidities,” and “Distrust in vaccine advice by health workers.” A large-scale study in the Chinese older adults indicated that female and unmarried older adults (70 years and older) living in urban areas and being functionally dependent/chronically ill were less likely to be vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccines; targeting on which, potential interventions were proposed through multivariate regression analysis.Citation9 Although this study demonstrated the influence of comorbidities and demographic characteristics on vaccine hesitancy, it did not make fully accounts for participants’ social and cognitive factors. One Chinese large cross-sectional survey found that concerns about contraindications, vaccine safety, and compromised mobility were the main reasons for hesitation to get vaccinated.Citation29 Similarly, there existed a significant hesitancy among older adults to get the influenza vaccines, with respondents being highly susceptible to influenza. Yet, those older people with the awareness of being prioritized members to get influenza vaccination were significantly less likely to refuse the vaccine.Citation30 Our study adds new important evidence to COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy, contributing to an in-depth understanding of the causes and complexities of vaccination hesitancy in the elderly as a special population.

Previous studies have investigated factors affecting COVID-19 vaccination in the older people in China.Citation20,Citation21,Citation31–33 However, most of these studies were based on small and regional samples, while our study took one step further through supporting the assumption that negative perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines may discourage vaccination in the older people, from various aspects of “Concerns about the vaccine safety and effectiveness,” “Religious beliefs,” and “Knowledge of upper respiratory tract infections.” Meanwhile, there also exist influencing factors that enhance the negative opinion of vaccines: “Information availability,” and “Community recommendations (recommendations made by neighbors living in the same residential compound)” may exacerbate negative perceptions of COVID-19 vaccination. To be specific, lack of vaccination knowledge was associated with cognitive bias and vaccine hesitancy. There was also a lack of clear public understanding of contraindications to COVID-19 vaccination and considerable evidence of the negative impacts of vaccine misinformation on social media;Citation34 some older people may self-identify as having contraindications to vaccination due to underlying chronic conditions; limited information sources may further affect vaccination. Worldwide research also help evidence this phenomenon, for example according to a study in Germany, the primary sources of information about COVID-19 vaccination were from discussions among family members, friends, or coworkers (81.8%), and from television and radio (77.1%);Citation35 another research in China found that older adults obtained less information about COVID-19 vaccination from trusted traditional media, but more of getting vaccination advices from family members, relatives, and friends.Citation36 In our study, whether vaccine-related information and advice actively provided by health workers was not included in the model. This result may be associated with the lack of trust in health providers and with the fact that older people were less likely to receive relevant advice from them. Our research also found that vaccination recommendation was the top influencing factor to vaccine hesitancy, in the context of limited information availability and sources. Chinese unique community gathering of older adults and information sharing have the potential to spread misinformation and generate vaccine hesitancy. Several research found that barely use of social media by older adults and those who live alone were with lower COVID-19 vaccination rates.Citation37,Citation38 Therefore, to address these potential problems and promote the effective dissemination of correct perceptions, it is essential to provide more sources of information on the effectiveness and safety of vaccination for older people, including official and authoritative channels, healthcare professionals, media and social media platforms, community education, and publicity.

In addition, it is important to consider cultural factors for insufficient vaccination. Since traditional Chinese culture, such as filial piety, plays a pivotal role in Chinese family power structure, the older people typically hold significant position.Citation19 As a result, it could be challenging for other family members to convince or compel them to receive vaccinations unless they are willing to do so. Therefore, the older people themselves should be the target population of vaccination promotion effort. To achieve this, it is recommended to implement special strategies that strengthen their awareness and recognition of the vaccine, including the production of customized information and education materials, community health education and talks, and vaccination experience share.

This study has both strengths and limitations. To date, it is the largest nationwide questionnaire survey in China, providing powerful data support and evidence. Our study fully considered the impact of other common upper respiratory pathogen vaccines on COVID-19 vaccination, increasing the reliability of the study. Quantitative analysis proved challenging for some of the indicators. It is possible that policies mandating early vaccination could influence participants’ perspectives. However, this study lacked analysis of the impact of policy. Since the first vaccine was made mandatory by government policy, it may be not applicable to assess the effects of first shot. Due to the selection of the population, our study population is not representative of the entire elderly population, especially those who do not go out or are less active. In completing the questionnaire, older adults may be not familiar with using digital devices, questionnaires may be filled out with the help of volunteers. In addition, this study was forced to terminate because of the COVID-19 pandemic at the end of 2022 in China.

Vaccine hesitancy among China’s older population is strongly influenced by cognitive bias and limited information sources, which may be deteriorated by interpersonal recommendations. It is important to disclose vaccine safety information through official channels as long as more safety data become available. The best way to counteract the current prevalence of misinformation about vaccines is to dilute it with an abundance of real, understandable scientific evidence.Citation39 Healthcare workers are an indispensable source of vaccination advice, and effective communication between them and the public will greatly facilitate vaccination.Citation40 Vaccination of older adults is a collective process in population level, which is both time-consuming and challenging to implement. Unlike the children, it cannot be enforced in the same way. However, if favorable factors for vaccination can be predicted in advance, it is possible to enhance the efficiency of vaccination through adjustments in public health policies and optimization of specific implementation routes. The above are expected to enhance the capability of older adults to cope with SARS-CoV-2 infections in the future.

Conclusions

The study’s prediction model could serve as a valuable clinical tool for predicting and evaluating vaccination rates among older adults, as well as providing recommendations to improve vaccine acceptance. This study could play a significant role in evaluating population-based vaccination and developing health policies for vaccinating older adults.

Authorship

Q.G takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript. Q.G, T.Y, D.Y.Y, K.H, L.J.P, F.L.W, F.L.Z, S.G.L, and W.M conceptualized and designed the study. D.L, Y.S.Z, and R.L participated in data acquisition; D.L, L.J.P, and Q.G analyzed and interpreted the data; and D.L and Q.G drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version to be published.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful for the support from Respiratory Disease Prevention and Control of Chinese Preventive Medicine Association.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Qualified researchers may request access to data with the consent of the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sadighi Akha AA. Aging and the immune system: an overview. J Immunol Methods. 2018;463:21–10. doi:10.1016/j.jim.2018.08.005.

- Chen X, Giles J, Yao Y, Yip W, Meng Q, Berkman L, Chen H, Chen X, Feng J, Feng Z, et al. The path to healthy ageing in China: a Peking University–Lancet Commission. The Lancet. 2022;400(10367):1967–2006. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01546-X.

- World population prospects - population division - united nations. [accessed 2024 Mar 4th]. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/MostUsed/.

- Dessie ZG, Zewotir T. Mortality-related risk factors of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 studies and 423,117 patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):855. [Published 2021 Aug 21]. doi:10.1186/s12879-021-06536-3.

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study [Published correction appears in Lancet. The Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1054–1062. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3.

- Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, Huang H, Zhang L, Zhou X, Du C, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934–943. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994.

- Shanghai municipal health commission what should the elderly pay attention to when they get vaccinated against the new crown virus? 2022 Jun 20 [accessed 2024 Mar 4th]. http://wsjkw.sh.gov.cn/yfjz/20220620/2c15d87ef628423c8c506eb4124a9189.html.

- Hong Kong Centre for Health Protection of the Department of Health Statistics on 5th wave of COVID-19. 2022 Jul 15 [accessed 2024 Mar 4th]. https://www.covidvaccine.gov.hk/pdf/5th_wave_statistics.pdf.

- Wang G, Yao Y, Wang Y, Gong J, Meng Q, Wang H, Wang W, Chen X, Zhao Y. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccination status and hesitancy among older adults in China. Nat Med. 2023;29(3):623–631. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02241-7.

- Ma M, Shi L, Liu M, Yang J, Xie W, Sun G. Comparison of COVID-19 vaccine policies and their effectiveness in Korea, Japan, and Singapore. Int J Equity Health. 2023 Oct 20;22(1):224. doi:10.1186/s12939-023-02034-x.

- Talic S, Shah S, Wild H, Gasevic D, Maharaj A, Ademi Z, Li X, Xu W, Mesa-Eguiagaray I, Rostron J, et al. Effectiveness of public health measures in reducing the incidence of covid-19, SARS-CoV-2 transmission, and COVID-19 mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2021 Dec 3;375:e068302. n2997. Published 2021 Nov 17. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068302.

- Lopez Bernal J, Andrews N, Gower C, Robertson C, Stowe J, Tessier E, Simmons R, Cottrell S, Roberts R, O’Doherty M, et al. Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines on COVID-19 related symptoms, hospital admissions, and mortality in older adults in England: test negative case-control study. BMJ. 2021;373:n1088. [Published 2021 May 13]. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1088.

- Huang YZ, Kuan CC. Vaccination to reduce severe COVID-19 and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26(5):1770–1776. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202203_28248.

- Lazarus JV, Wyka K, White TM, Picchio CA, Rabin K, Ratzan SC, Parsons Leigh J, Hu J, El-Mohandes A. Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data from 23 countries in 2021. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3801. [Published 2022 Jul 1]. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31441-x.

- Wu J, Li Q, Silver Tarimo C, Wang M, Gu J, Wei W, Ma M, Zhao L, Mu Z, Miao Y. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Chinese population: a large-scale national study. Front Immunol. 2021;12:781161. [Published 2021 Nov 29]. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.781161.

- Taylor L. Covid-19: Hong Kong reports world’s highest death rate as zero covid strategy fails. BMJ. 2022;376:o707. [Published 2022 Mar 17]. doi:10.1136/bmj.o707.

- Freeman D, Loe BS, Chadwick A, Vaccari C, Waite F, Rosebrock L, Jenner L, Petit A, Lewandowsky S, Vanderslott S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol Med. 2022;52(14):3127–3141. doi:10.1017/S0033291720005188.

- Transcript of the Chinese State Council Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism Press Conference. 2022 Jul 23 [accessed 2024 Mar 4th]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/s3574/202207/f920442a8a4845e7833ca8d7e7cd876e.shtml.

- Zhang Y, Wang Y, Ning G, He P, Wang W. Protecting older people: a high priority during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. 2022;400(10354):729–30. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01530-6.

- Wu J, Li Q, Silver Tarimo C, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy among chinese population: a large-scale national study. Front Immunol. 2021;12:781161. Published 2021 Nov 29. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.781161.

- Wang J, Yuan B, Lu X, Liu X, Li L, Geng S, Zhang H, Lai X, Lyu Y, Feng H, et al. Willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine among the elderly and the chronic disease population in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(12):4873–4888. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2009290.

- Cox F, King C, Sloan A, Edgar DJ, Conlon N. Seasonal influenza vaccine: uptake, attitude, and knowledge among patients receiving immunoglobulin replacement therapy. J Clin Immunol. 2021 Jan;41(1):194–204. doi:10.1007/s10875-020-00922-3.

- Elgendy MO, Abdelrahim MEA. Public awareness about coronavirus vaccine, vaccine acceptance, and hesitancy. J Med Virol. 2021;93(12):6535–6543. doi:10.1002/jmv.27199.

- Wang MW, Wen W, Wang N, Zhou M-Y, Wang C-Y, Ni J, Jiang J-J, Zhang X-W, Feng Z-H, Cheng Y-R, et al. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among healthcare workers and non-healthcare workers in China: a survey. Front Public Health. 2021 Aug 2. 9:709056. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.709056.

- Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J R Stat Soc: Ser B (Methodological). 1996;58(1):267–288. doi:10.1111/j.2517-6161.1996.tb02080.x.

- Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw. 2010;33(1):1–22. doi:10.18637/jss.v033.i01.

- State Department COVID-19 Prevention and Control Mechanism Integrated Group. Notice on further optimization of the implementation of measures for the prevention and control of the COVID-19 outbreak. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-11/11/content_5726122.htm.

- Euronews. China expands lockdowns as COVID-19 cases hit daily record. https://www.npr.org/2022/11/24/1139147636/china-expands-lockdowns-as-covid-19-cases-hit-daily-record.

- Qin C, Yan W, Du M, Liu Q, Tao L, Liu M, Liu J. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine booster dose and associated factors among the elderly in China based on the health belief model (HBM): a national cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:986916. [Published 2022 Dec 15]. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.986916.

- Hou Z, Guo J, Lai X, Zhang H, Wang J, Hu S, Du F, Francis MR, Fang H. Influenza vaccination hesitancy and its determinants among elderly in China: a national cross-sectional study. Vaccine. 2022;40(33):4806–4815. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.06.063.

- Lv L, Wu XD, Yan HJ, Zhao SY, Zhang XD, Zhu KL. The disparity in hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination between older individuals in nursing homes and those in the community in Taizhou, China. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):828. [Published 2023 Dec 9]. doi:10.1186/s12877-023-04518-5.

- Siu JY, Cao Y, Shum DHK. Perceptions of and hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination in older Chinese adults in Hong Kong: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):288. [Published 2022 Apr 6]. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-03000-y.

- Wagner AL, Huang Z, Ren J, Laffoon M, Ji M, Pinckney LC, Sun X, Prosser LA, Boulton ML, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, et al. Vaccine hesitancy and concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness in Shanghai, China. Am J Preventative Med. 2021;60(1 Suppl 1):77–86. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.09.003.

- Ruggeri K, Vanderslott S, Yamada Y, Argyris YA, Većkalov B, Boggio PS, Fallah MP, Stock F, Hertwig R. Behavioural interventions to reduce vaccine hesitancy driven by misinformation on social media. BMJ. 2024 Jan 16;384:e076542. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-076542.

- Haß W, Orth B, von Rüden U. COVID-19-Impfstatus, genutzte Informationsquellen und soziodemografische Merkmale – Ergebnisse der CoSiD-Studie [COVID-19 vaccination status, sources of used information and socio-demographic characteristics-results of the CoSiD study]. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz. 2023;66(8):846–56. doi:10.1007/s00103-023-03736-x.

- Lin Y, Hu Z, Zhao Q, Alias H, Danaee M, Wong LP. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: a nationwide online survey in China. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(12):e0008961. [Published 2020 Dec 17]. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008961.

- Gong F, Gong Z, Li Z, Min H, Zhang J, Li X, Fu T, Fu X, He J, Wang Z, et al. Impact of media use on Chinese public behavior towards vaccination with the COVID-19 vaccine: a latent profile analysis. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(10):1737. [Published 2022 Oct 17]. doi:10.3390/vaccines10101737.

- Zhang D, Zhou W, Poon PK, Kwok KO, Chui TWS, Hung PHY, Ting BYT, Chan DCC, Wong SYS. Vaccine resistance and hesitancy among older adults who live alone or only with an older partner in community in the early stage of the fifth wave of COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(7):1118. [Published 2022 Jul 13] doi:10.3390/vaccines10071118.

- Marks P, Califf R. Is vaccination approaching a dangerous tipping point? JAMA. 2024;331(4):283–284. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.27685.

- Astuti SI, Sufehmi H, Wilhelm E. Centring health workers and communities is key to building vaccine confidence online. BMJ. 2024 Jan 16;384:q82. doi:10.1136/bmj.q82.